Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.2 Montevideo dez. 2021 Epub 01-Dez-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2098

Original Articles

Depressive symptoms and their impact on social representation of depression: a study with adolescents

1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil, alexandrecdmello@gmail.com

Depression has been portrayed as the evil of the century, becoming a public health problem that has affected millions of people worldwide. This study aimed to understand how adolescents represent depression. One hundred and sixty-eight high school students aged 14 to 18 years participated, from public and private schools in João Pessoa-Paraíba, Brazil. We used the Free Association of Words Technique (TALP), a sociodemographic questionnaire, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The social representation of depression anchored in subjective experiences was observed, emphasizing the individual aspects of this phenomenon, such as sadness, loneliness, anguish, suffering and suicide. The adolescents presented depressive symptoms in 21.4 % of the cases, and these percentages are higher when compared to other studies in the area. It is hoped that this study can promote preventive actions in the school context and reflect on ways to raise awareness of depression as a disorder with multiple causes.

Keywords: depression; adolescents; social representation; TALP; HADS

A depressão tem sido retratada como o mal do século, tornando-se um problema de saúde pública que tem afetado milhões de pessoas no mundo. Este estudo objetivou compreender como os adolescentes representam a depressão. Participaram 168 estudantes do ensino médio, com idades de 14 a 18 anos, de escolas públicas e privadas de João Pessoa-Paraíba, Brasil. Utilizou-se a Técnica de Associação Livre de Palavras (TALP), Questionário sociodemográfico e a Escala de Ansiedade e Depressão Hospitalar (HADS). Observou-se a representação social da depressão ancorada em vivências subjetivas enfatizando os aspectos individuais desse fenômeno como tristeza, solidão, angústia, sofrimento e suicídio. Os adolescentes apresentaram sintomatologia depressiva em 21,4 %, sendo estes percentuais acentuados quando comparados com outros estudos na área. Espera-se que este estudo possa promover ações de prevenção no contexto escolar e reflexões sobre meios de conscientização da depressão como um transtorno de causas múltiplas.

Palavras-chave: depressão; adolescentes; representação social; TALP; HADS

La depresión ha sido retratada como el mal del siglo, convirtiéndose en un problema de salud pública que ha afectado a millones de personas en todo el mundo. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo comprender cómo los adolescentes representan la depresión. Participaron 168 estudiantes de secundaria, de 14 a 18 años, de escuelas públicas y privadas en João Pessoa-Paraíba, Brasil. Se utilizó la técnica de asociación de palabras libres (TALP), Cuestionario sociodemográfico y la Escala de ansiedad y depresión hospitalaria (HADS). Se observó la representación social de la depresión anclada en experiencias subjetivas que enfatizan los aspectos individuales de este fenómeno como la tristeza, la soledad, la angustia, el sufrimiento y el suicidio. Los adolescentes presentaron síntomas depresivos en 21.4 %, estos porcentajes se acentuaron en comparación con otros estudios en el área. Se espera que este estudio pueda promover acciones preventivas en el contexto escolar y reflexiones sobre formas de crear conciencia sobre la depresión como un trastorno de múltiples causas.

Palabras clave: depresión; adolescentes; representación social; TALP; HADS

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-esteem, disturbed sleep or appetite, feeling tired, and lack of concentration. It can be long-lasting or recurrent, substantially impairing the individual's ability to function. Today, the disorder is treated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a public health problem, and it is estimated that more than 322 million people of all ages suffer from it. Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and in its most severe state can lead to suicide (WHO, 2017).

According to data from the WHO (2017), approximately 5.8 % of the Brazilian population suffers from depression, totaling approximately 11.5 million cases registered in the country; presenting the highest rate in Latin America and the second highest in the Americas, behind the United States, Australia, and Estonia, which register 5.9 % of the population with depressive disorder.

In Brazil, the results of the study on the prevalence of depressive symptoms in adolescents from the public school network of Salvador indicate the predominance of depressive symptoms in 7.72 % of students (Couto, Reis & Oliveira, 2016). Looking back to the study of adolescents is of utmost importance, not only because of the large number of them in Brazil and worldwide, but also because this is a specific stage of life that needs to be cared for due to its changes, its experiences, and its impacts on adulthood. According to Silva et al. (2019), it is at this stage of life that adolescents manifest peculiar characteristics, such as the need to be accepted by the social group and the search for their identity. For Palacio, Pinto, Monte, Palacio and Aranha (2021) adolescence presents a greater burden in the lives of individuals, since they need to assume social responsibilities and acquire values that will guide their behaviors, which are often linked to the groups they belong to.

Having as a research source the social representations (SR) of adolescents about depression, the school environment was adopted for data collection, since it is in this space that adolescents stay for a long time and build social bonds. Moreover, the studies by Pereira Simões et al. (2018) and Santos, Simões, Erse, Façanha and Marques (2014) ensure that the school is a privileged place for a preventive intervention regarding the early perception of mental disorders; since they are where adolescents spend most of their time in academic and extra-class activities, and where they have the strongest social interactions. In this sense, their training agents are elements in a privileged circumstance to signal and refer adolescents at risk, being alert to the signs of depression.

According to Pereira Simões et al. (2018), the school is the center of mental health promotion and should be understood as a privileged place that can invest not only in prevention, but also in interventions aimed at health promotion, taking into account the variable well-being of adolescents. Santos et al. (2014), also highlight that the school institution reveals itself as a core promoter of mental health by applying strategies that favor the development of skills and competencies that promote mental health.

But in addition to early diagnosis and mental health promotion, school can also be a place where individuals can experience negative relational experiences such as bullying, which is one of the risk factors for depressive and anxiety disorders in the school environment, compromising the mental health of the victims. According to the studies by Naveed, Waqas, Aedma, Afzaal and Majeed (2019), bullying can trigger negative mental as well as social and physical health outcomes for those involved. According to the authors, bullies and victims of bullying can develop depression, anxiety, low school performance, social maladjustment, and high-risk behaviors such as substance abuse, self-injury, and suicide. In a survey conducted by the aforementioned authors, involving 452 adolescents from Pakistan and involved in bullying incidents, it was found that 35.8 % had mild depressive symptoms, 19.5 % moderate, 7.3 % moderately severe, and 4.2 % severe symptoms.

The psychological suffering experienced by adolescents contributes to their dropping out of school for not being able to cope with such a situation. Quiroga, Janosz, Bisset and Morin (2013) reiterate that school dropout is directly related to depressive symptoms, especially when these are caused by the feeling of inability or incompetence.

Such data were also found in the study by Coutinho, Pinto, Cavalcanti, Araújo and Coutinho (2016), where they observed that adolescents with depressive symptoms scored the lowest averages in quality of life, especially in the bullying factor, meaning that social reproach causes a feeling of fear, rejection, and anxiety, causing the victims' quality of life to be affected.

According to the World Health Organization and Columbia University (2016), depression is a common mental disorder involving persistent sadness or loss of interest or pleasure accompanied by various symptoms such as: disturbed sleep or appetite, feelings of guilt or low self-esteem, feelings of tiredness, lack of concentration, difficulty making decisions, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts or acts. Depression is a mental disorder, therefore, different from normal mood swings and short-lived emotional reactions to the daily challenges of life. A person with depression has considerable difficulty in their daily activities at home, at school or at work, or in society, impacting the person themselves and those around them. Therefore, depression has direct effects on the subject's relational and subjective development, interfering in their way of seeing the world and relating to it.

As stated by Coutinho et al. (2016), the prevalence of depression in the context of adolescence is directly related to factors that are not only biological, but also psychosocial. Therefore, in order to understand the phenomenon of depression in adolescents from a psychosocial perspective, this study used the Theory of Social Representations and has as its general objective: to apprehend the SR on depression elaborated by adolescents, considering that this theory gives us subsidies to analyze how adolescents think the phenomenon of depression, allowing access to their experiences and beliefs about depression. For Mendonça and Lima (2015), the SRs emerge from the need for adjustment of people who need to identify, conduct and solve problems that are presented to them, transforming the unknown into known. “The purpose of all representations is to make familiar something unfamiliar” (Moscovici, 2015, p. 54).

SRs allow individuals to understand and explain reality through the construction of new knowledge, having as function to situate individuals and groups in the social field, allowing them to develop a social and personal identity. As common sense knowledge, they also guide behaviors and practices, being characteristic of SR the fact that they are both product and process of human activity (Almeida & Santos, 2011).

Abric (2001) highlights within the Theory of Social Representations, the Central Core Theory (CCT), which does not intend to replace the theoretical approach of Moscovici's SR, but to contribute with it, since Abric understands that every representation is organized around a central core, consisting of one or a few elements that give the representation its meaning.

CCT consists in the analysis of the internal structure of the SR and its elements, which are structured in a sociocognitive system presenting specific characteristics, organized by a central core that is composed of elements associated with values and norms (Mendonça & Lima, 2015; Wachelke & Wolter, 2011), and by peripheral elements that incorporate meaning to the representation and are related to individual characteristics and the immediate and eventual context (Azevedo, Miranda & Souza, 2012).

With this theoretical perspective and emphasis on the central core, this study aims to understand the SR of depression, elaborated by adolescent high school students from schools in João Pessoa-Paraíba, Brazil, making a comparative analysis of the representations of adolescents with and without depressive symptoms. To this end, a screening instrument for depressive symptoms was used: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). This research had as theoretical assumption that people who score higher on the depression scale (with depressive symptoms), will have representations with a higher number of evocations related to symptoms and emotional issues such as suicide, fear, and anguish, having in mind that such representations are shaped by subjective experiences. This is associated with what is highlighted by Monteiro, Coutinho and Araújo (2007), when they state that SR are conceived by social, cognitive and affective processes that are expressed in social interactions, socially representing the meaning acquired in their lives.

Method

Participants

This research was composed of 168 adolescents from the public and private networks of the city of João Pessoa - Paraíba, Brazil; taking into account the definition of adolescence established by the Statute of Children and Adolescents (ECA) that defines adolescence as the period between 12 and 18 years of age (Brasil, 2015). Participants were selected in a non-probabilistic manner and by convenience.

Instruments

The TALP was used with the objective of identifying and describing the structure of the SR of depression elaborated by adolescents; for this, the participants were asked to evoke the first 5 (five) words that came to mind from the inductive stimulus depression related to the object of SR of the study, as prescribed by Wolter and Wachelke (2013). Then, the sociodemographic questionnaire was used to obtain information about the characteristics of the participants, with the aim of knowing the social group from which emerged the SRs of interest to this study.

We also used the HADS, which is an instrument for screening anxiety and depression symptoms, applicable to both the general and clinical populations. This instrument was validated for the Brazilian context and is composed of 14 items divided into two subscales, each composed of 7 items: HAD-Anxiety (Cronbach's alpha: .68), comprised by the odd items and HAD-Depression (Cronbach's alpha: .77), involving the even items. Items are answered on a four-point agreement scale, ranging from zero to three points (from absent to very frequent) with a maximum score of 21 points per subscale. The cut-off points obtained in the literature were ≥ 9 points for each disorder, proposed from theoretical and empirical criteria derived from clinical samples (Botega et al., 1995; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). Faro, Fernandes Araújo, Maciel, Lima and Souza (2021) tested the factor structure and gender invariance of the scale in a non-clinical sample of 657 adolescents in Brazil (Mage = 16.3; SD = 1.19) and found satisfactory evidence of factor structure validity and gender invariance for this population. The Composite Reliability was also satisfactory in that study, with an average of the variance explained by the items of 0.31, with a Cronbach's alpha of .84 for the total scale; .81 and .69 for the anxiety and depression subscales, respectively. For the present research, only the depression subscale (HAD-depression) composed of the 7 odd items of the total scale was used.

Procedures and ethics

At first, the project was sent to the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Health Sciences Center (CEP/CCS) of the Federal University of Paraíba, in order to verify the ethical parameters, based on resolution 510/16. The research was approved by the CEP/CCS under Protocol No. 0485/16, CAAE: 58586816.9.0000.5188.

After approval by the Research Ethics Committee, contact was made with public and private schools in the city of João Pessoa-Paraíba, in order to request the consent of the school for the research, with those responsible for the school unit. With this authorization, the parents of the adolescents were sent the research Informed Consent Form (ICF); after parental or guardian authorization, the Informed Consent Form was given to the adolescents by the participant, so that they could sign if they wished to participate in the study. After this protocol, the application of the data collection instruments began, starting with the TALP and then the application of the HAD scale and the sociodemographic questionnaire.

Data analysis

The sociodemographic questionnaire was analyzed through descriptive statistics, with simple frequency calculations, performed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) - version PASW 21.0. The results allowed information to be obtained about the characteristics of the participants, aiming to know the group of belonging from which the SRs of interest for this study emerge.

Data from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) - version PASW 21.0.

The TALP data were analyzed with the help of the software, Interface de R pourles Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (Iramuteq), developed by French researcher Pierre Ratinaud. In this study, prototypical and similarity analysis were used. The prototypical analysis consists of a technique developed by researchers in the field of SR that aims to identify the representational structure through criteria of frequency, which is an indicator of the degree of sharing of evocations in the researched group, and of evocation order (rang) of the words generated in a TALP, considered as a salience index. In this analysis, Iramuteq organizes the words evoked in a four quadrant diagram according to their frequency and average evocation order, graphically demonstrating the words that belong to the central core and the peripheral system of the SRs (Camargo & Justo, 2013; Wachelke & Wolter, 2011).

The similarity analysis is based on graph theory and allows identifying the co-occurrences between evocations, and its result shows indications of the connectedness between the structures of the words' content. This analysis provides a figure where the sizes of the vertices are proportional to the frequencies of the words and the edges demonstrate the strength of the co-occurrence between the evocations (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

Results and Discussion

Regarding the sociodemographic data of the 168 high school adolescents, the majority was female 53.6 % and the ages ranged from 14 to 18 years (M = 16.27 years and SD = 1.09) with a predominance of the age group of 16 years (36.9 %), with the majority of students belonging to the 1st year of high school 45.2 % and the percentage frequency of students who consider themselves depressed was 12.5 %.

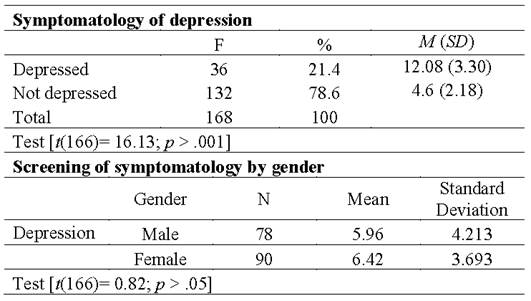

The analysis of the HADS, depression subscale, was performed in order to verify the tracking of depressive symptomatology in the study participants so that these data could be used as a variable in the similarity analysis and thus it was possible to identify the SR of depression by adolescents with and without depressive symptomatology. The cut-off points pointed out by Zigmond and Snaith (1983) were adopted, indicating as without depression from 0 to 8, and with depression ≥ 9. On the depression subscale, the participants in this study obtained a mean of 6.21 and standard deviation of 3.93 (ranging from 0-21). Table 1 contains the frequency of the presence of depression symptomatology in the participants studied.

Of the 168 adolescents in this study, 21.4 % had depressive symptoms. Although the participants, in general, scored without depression symptomatology, since the mean of the subscale (Depression = 6.21, SD = 3.93) was below the cut-off point determined by Zigmond and Snaith (1983), the presence of adolescents who scored above the cut-off point, indicating the depressive disorder symptomatologies, is significant. With regard to depressive symptomatology, the adolescents' mean score was M = 12.08 (SD = 3.30) for adolescents with symptomatology and M = 4.6 (SD = 2.18) for those without symptomatology, with a significant t-test of (t(166)= 16.13; p > .001).

The study conducted by Coutinho et al. (2016) with 204 adolescents from public schools in João Pessoa-Paraíba, points to a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in females. Results were also found by Jatobá and Bastos (2007), Rocha, Ribeiro, Pereira, Aveiro and Silva (2006), showing that women present more symptoms of anxiety and depression than men.

Although the literature shows significant differences regarding symptomatology, specifically depressive symptoms, between genders, in the present study there was no statistically significant difference between genders (t(166)= 0.82; p > .05).

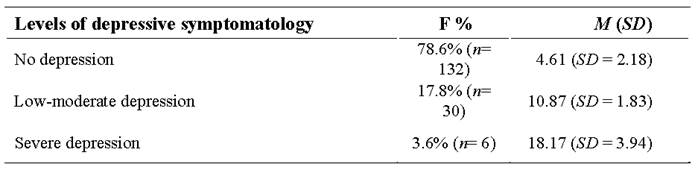

Considering that among the participants there is a significant presence of adolescents with depressive symptoms (21.4 %), although the general mean (6.21; SD = 3.93) describes the absence of depression, a new analysis was performed, in which instead of considering only the two levels of depressive symptoms (with depression and without depression), three levels of depression were adopted, considering the HADS scores: without depression (0 to 8), low-moderate depression (9 to 14) and severe depression (15 to 21), according to Table 2.

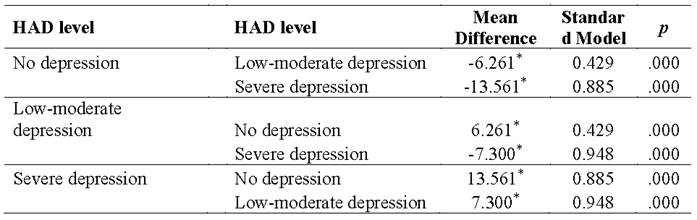

To verify whether the differences between the means of the levels are statistically significant, a one-way ANOVA was performed. The test showed a significant difference between the means of the levels of depressive symptoms (F(2.165)= 205.5; p < .001). We also performed a Tukey post hoc test in order to identify where the means differed in relation to the levels (Table 3).

Table 3: Teste Post Hoc Tukey HSD: multiple comparisons between the means of the adolescents in relation to the level of depression

Note: *The mean difference is significant at the .05 level.

The Post Hoc test showed that there was a significant difference among all levels of depressive symptoms. That is, for the participants of this study, we found three levels of depressive symptomatology severity.

After the HAD analysis, the Iramuteq prototypical analysis was performed, followed by a similarity analysis. This analysis counted on data from the HAD scale taking into consideration the variable presence/absence of depressive symptomatology, with the purpose of understanding the representation that adolescents with and without depressive symptomatology have in relation to the phenomenon of depression.

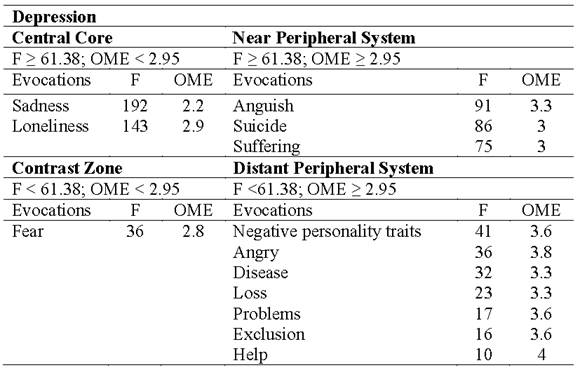

The prototypical analysis was performed with the help of Iramuteq, which generated a diagram with four cells of the SR structure, according to (Table 4) for the inducing stimulus depression, containing the evoked words, their frequencies and the mean order of evocation (OME). According to Camargo and Justo (2013), this diagram represents four dimensions of the SR structure. The adolescents provided five evocations to the stimulus word and no omitted cases. There were 840 evocations, and an overall average frequency of 2.95, with the minimum frequency considered for inclusion of the words in the quadrants being 10, approximately 6 % of the sample size. The evocations were grouped by semantic criteria according to Wachelke and Wolter (2011), thus they can be classified according to a common meaning.

Table 4: Diagram of evocations referring to the stimulus depression

Notes: F = frequency; OME = mean order of evocations.

According to Wachelke and Wolter (2011), the core zone comprises words with high frequency (a higher than average frequency) and low evocation order (responses provided by a large number of participants and readily evoked). For Rateau (2004), a set of beliefs organized around a common core is being shared through which defines the identity and homogeneity of a social group.

In this study, the two words that refer to central elements of the SR about depression were sadness and loneliness, and express a representation objectified in psycho-affective feelings. The feelings of sadness and loneliness become fundamental bases for the understanding of the psychosocial factors that trigger this disorder. In this sense, depression in adolescence tends to modify the behavior of social actors, since it can lead them to distance themselves from their peer group and cause a feeling of emptiness and loneliness (Ribeiro, Medeiros, Coutinho & Carolino, 2012).

The adolescents in the present study anchored the SR of depression in sadness, thus corroborating the study conducted by Barros and Coutinho (2005), who, when conducting research with adolescents in private and public schools in João Pessoa, found that the SR of depression were anchored mainly in factors related to sadness.

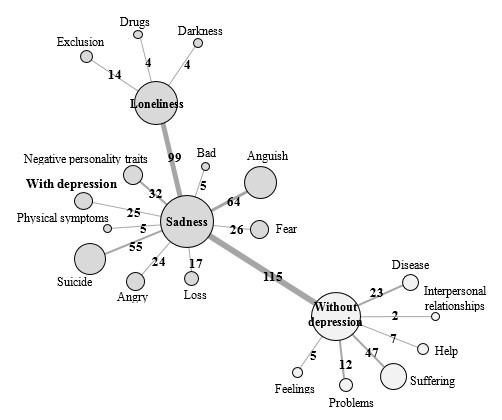

The similarity analysis generated the graph of Figure 1 which refers to the representations of the adolescents in face of depression, containing the frequency and the strength of the co-occurrence among the words. According to Abric (2003), the analysis of the co-occurrence of the categories allows the visualization of the SR organization from the strength with which the elements are linked to each other. In this way, a maximum tree is obtained that presents the centrality and the connectedness of the various elements.

The central core of the SR of adolescents with and without depressive symptomatology is objectified in sadness, where it presents co-occurrence forces of (25) with adolescents who present symptomatology and co-occurrence of (115) with those who do not present depressive symptomatology.

The adolescents with symptoms represent depression by focusing on feelings that encompass the categories sadness, fear, anger, anguish, loss, and loneliness. They also construct this representation based on negative personality characteristics (coldness, pessimism, low self-esteem, incapability, and shyness), physical symptoms (insomnia, sleepiness, and lack of appetite), and suicide. The feeling of darkness depicted in the similarity graph branches out with co-occurring strengths of (14) for the category exclusion, and of (4) for the categories drugs and darkness.

The sample characterized with no depressive symptoms, compared to the group with depressive symptoms, represented depression as suffering (47), disease (23), problems (12), help (5) and interpersonal relationships (2), with the category feelings (5) being the only one in common to both groups in the sample. It can be noticed that this group of adolescents with no depressive symptoms understands depression as a suffering that may trigger a disease, and in this sense, it is necessary to look for or even help people who are in depressive situations.

Therefore, it can be stated that the evocations of sadness and loneliness are central to the SR of depression elaborated by the adolescents, since they organize the other elements around them and maintain significant connectivities with them. In this way, the evocations of sadness and loneliness configure the organizing role about the representational object of the present study. According to Nolan, Flynn and Garber (2003), adolescents with depressive disorders are often rejected by the people with whom they live, a representation found in this study with the word exclusion (14). Ribeiro, Nascimento and Coutinho (2010) point out that depression is linked to psycho-affective aspects, such as sadness and love disillusionment, and psychosocial aspects, in which they evidenced difficulty in social relationships, social isolation, low school performance, difficulties in family relationships, low self-esteem, and ideas or attempts of suicide experienced during depression. These representations can be found in the present study with the words: anguish, suicide, fear, and negative personality characteristics.

Final Considerations

The incidence of depressive symptoms has intensified and become one of the most prevalent disorders in adolescence, and has affected social interactions and educational development. In this sense, developing studies focused on this student population is of great relevance because the occurrence of depression in this specific stage of life implies an increase in school dropout when feelings of incapacity and incompetence may arise. The school environment is fundamental for adolescents to develop their social and emotional skills, through studies that serve as mechanisms to identify and monitor health risk behaviors.

The present study aimed to identify the SR of adolescents inserted in the educational context about depression, making a comparative analysis of the representations of adolescents with and without depressive symptoms. The TALP was used, which allowed access to the latent contents that constitute the imaginary of the social group, contributing to the construction of the structure of a SR of depression from what was readily evoked.

It was observed in the TALP that the adolescents represent depression as sadness, loneliness, anguish, suffering, and suicide anchored on subjective experiences of the individual, emphasizing individual aspects of this phenomenon, without a broader vision that encompasses the social issue.

The SR of depression elaborated by the adolescents in the present study as a psychological factor and involving affective issues has revealed that depression has not been perceived as a disease. This fact can be evidenced by the existing relationship, in the common sense, between sadness and depression. This fact can cause the absence of the search for help from a mental health professional, because they may see sadness as a passing feeling, not perceiving it as a pathological symptom.

Assuming that the SR are considered in a broad sense as social thought, and that they are essential in human relations, since they give meaning to reality, it becomes, then, necessary to create awareness actions aimed at adolescents in order to guide them regarding the importance of understanding depression as a disease with multiple and not individual causes, so as not to blame the subject who suffers. The SR, in fulfilling its function of guidance, acts as a guide to behaviors and practices adopted by social subjects, in this sense, functioning as an anticipation of actions, determining the cognitive attitude and prescriptive nature of social agents.

As a limitation of the present study, we can consider the possible influence of social desirability on the answers obtained. Thus, it is suggested that new studies of SR explore the depressive phenomenon in adolescents enrolled in public and private high schools, in order to investigate probable changes in the core of SR found in this study.

REFERENCES

Abric, J. C. (2001). O estudo experimental das representações sociais. Em D. Jodelet (Ed.), As representações sociais (pp. 155-171). Rio de Janeiro: UERJ. [ Links ]

Abric, J. C. (2003). Abordagem estrutural das depressive symptoms and their impact on social representation of depression epresentações sociais: desenvolvimentos recentes. In: P. H. F. Campos & M. C. Loureiro (Orgs.), Representações sociais e práticas educativas (pp. 37-57). Goiânia: UCG. [ Links ]

Almeida, A. M. O. & Santos, M. F. S. (2011). A Teoria das Representações Sociais. Em: C. V. Torres, & E. R. Neiva, Psicologia Social: principais temas e vertentes (pp. 288- 295). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Azevedo, J. C., Miranda, F. A., & Souza, C. H. M. (2012). Reflexões acerca das estruturas psíquicas e a prática do Ciberbullying no contexto da escola. Intercom: Revista Brasileira de Ciências da Comunicação, 35(2), 247-265. doi:10.1590/S1809-58442012000200013 [ Links ]

Barros, A. P. R. & Coutinho, M. P. L. (2005). Depressão na adolescência: Representações Sociais. In M. P. L. Coutinho & A. A. W. Saldanh, (Orgs.), Representação Social e práticas de pesquisa (pp 39-67). João Pessoa: UFPB. [ Links ]

Brasil. (2015). Estatuto da criança e do adolescente (1990): Lei n. 8.069 (1990, julho 13) e legislação correlata. Brasília: Edições Câmara. [ Links ]

Botega, N. J., Bio, M. R., Zomignani, M. A., Garcia, Jr. C., & Pereira, W. A. B. (1995). Transtornos do humor em enfermaria de clínica médica e validação de escala de medida (HAD) de ansiedade e depressão. Revista de Saúde Pública, 29(5), 359-363. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89101995000500004 [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V. & Justo, A. M. (2013). Iramuteq: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, 21(2), 513-518. doi: 10.9788/TP2013.2-16 [ Links ]

Coutinho, M. P. L., Pinto, A. V. L., Cavalcanti, J. G., Araújo, L. S. de & Coutinho, M. L. (2016). Relação entre depressão e qualidade de vida de adolescentes no contexto escolar. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 17(3), 338-251. doi 10.15309/16psd170303 [ Links ]

Couto, I. S. L., Reis, D. M. L., & Oliveira, I. R. (2016). Prevalência de sintomas de depressão em estudantes de 11 a 17 anos da rede pública de ensino de Salvador. Rev. Ciênc. Méd. Biol., 15(3), 370-374. doi: 10.9771/cmbio.v15i3.18205 [ Links ]

Faro, A., Fernandes de Araújo, L., Carneiro Maciel, S., Souza de Lima, T. J. & Cunha de Souza, L. E. (2021). Structure and invariance of the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) in adolescents. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(2), e-2069. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2069 [ Links ]

Jatobá, J. V. N., & Bastos, O. (2007). Depressão e ansiedade em adolescentes de escolas públicas e privadas. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 56(3), 171-179. doi: 10.1590/S0047-20852007000300003 [ Links ]

Mendonça, A. P., & Lima, M. E. O. (2015). Representações sociais e cognição social. Psicologia e Saber Social, 3(2), 191-206. [ Links ]

Monteiro, F. R., Coutinho, M. P. L., & Araújo, L. F. (2007). Sintomatologia depressiva em adolescentes do ensino médio: um estudo das representações sociais. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 27(2), 224-235. doi: 10.1590/S1414-98932007000200005 [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (2015). Representações sociais: investigações em psicologia social (11 ed.). (P. A. Guareschi, Trad.). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Naveed, S., Waqas, A., Aedma, K. K., Afzaal, T., & Majeed, M. H. (2019). Association of bullying experiences with depressive symptoms and psychosocial functioning among school going children and adolescents. BMC research notes, 12(1), 198. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4236-x [ Links ]

Nolan, S.A., Flynn, C., & Garber, J. (2003). Relações prospectivas entre rejeição e depressão em jovens adolescentes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 745-755. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745 [ Links ]

Organização Mundial de Saúde e Columbia University. (2016). Group Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) for Depression (WHO generic field-trial version 1.0). Geneva: WHO. [ Links ]

Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Obtido de http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254610/1/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf?ua=1 [ Links ]

Palacio, D. Q. A., Pinto, A. G. A., Monte, T. da C. L. do., Palacio, B. Q. A., & Aranha, Á. C. M. (2021). Saúde mental e fatores de proteção entre estudantes adolescentes. Interação, 21(1), 72-86. doi: 10.53660/inter-91-s109-p72-86 [ Links ]

Pereira Simões, R. M., Santos, J. C., Façanha, J., Erse, M., Loureiro, C., Marques, L. A., & Matos, E. (2018). Promoção do bem-estar em adolescentes: contributos do projeto +Contigo. Portuguese Journal of Public Health, 36(1), 41-49. doi: 10.1159/000486468 [ Links ]

Quiroga, C. V., Janosz, M., Bisset, S. & Morin, A. J. S. (2013). Early adolescent depression symptoms and school dropout: Mediating processes involving self-reported academic competence and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 552-560. doi: 10.1037/a0031524 [ Links ]

Rateau, P. (2004). Princípios organizadores e núcleo central das representações sociais. Hipóteses empíricas. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 56(1-2), 93-104. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, K. C. S., Medeiros, C. S., Coutinho, M. P. L., & Carolino, Z. C. G. (2012). Representações sociais e sofrimento psíquico de adolescentes com sintomatologia depressiva. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 14(3), 18-33. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, K. C. S., Nascimento, E. S., & Coutinho, M. P. L. (2010). Representação social da depressão em uma instituição de ensino da rede pública. Revista Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, 30(3), 448-463. doi: 10.1590/S1414-98932010000300002 [ Links ]

Rocha, T. H. R., Ribeiro, J. E. C., Pereira, G. A., Aveiro, C. C., & Silva, L. C. A. (2006). Sintomas depressivos em adolescentes de um colégio particular. Psico USF, 11(1), 95-102. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712006000100011 [ Links ]

Santos, J.C, Simões, R.M.P, Erse, M.P.Q de A., Façanha, J.D.N, & Marques, L.A.F.A. (2014). Impacto do treinamento “+ Contigo” no conhecimento e nas atitudes dos profissionais de saúde sobre o suicídio. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 22(4), 679-684. doi: 10.1590 / 0104-1169.3503.2467 [ Links ]

Silva, G., Ribeiro, I., Silva, H., Rezende, T., Belo, V., & Romano, M. (2019). Perfil e demandas de saúde de adolescentes escolares. Revista de Enfermagem da UFSM, 9, e57. doi: 10.5902/2179769233510 [ Links ]

Wachelke, J. & Wolter, R. (2011). Critérios de construção e relato da análise prototípica para representações sociais. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 27(4), 521-526. [ Links ]

Wolter, R. P., & Wachelke, J. (2013). Índices complementares para o estudo de uma representação social a partir de evocações livres: raridade, diversidade e comunidade. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 15(2), 119-129. [ Links ]

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxietyand Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361-370. [ Links ]

Correspondence: Alexandre Coutinho de Mello, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil. E-mail: alexandrecdmello@gmail.com

How to cite: Coutinho, A., Carneiro, S., Vasconcelos, C. C., & Cabral, J. V. (2021). Depressive symptoms and their impact on social representation of depression: a study with adolescents. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(2), e-2098. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2098

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. A. C. M. has contributed in b, c, d, e; S. G. M. in a, c, e; C. C. V. D. in b, c; J. V. C. S. in b, d.

Received: March 09, 2020; Accepted: August 30, 2021

texto em

texto em