Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.1 Montevideo jun. 2021 Epub 01-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2398

Original Articles

Positive body image and social networks in adult population of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires

1 Universidad de Palermo. Argentina

2 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet). Argentina gongoravanesa@gmail.com

The positive body image has a preeminent protective function in the current media, however, to date, there are no studies linking it to social networks. The objective of this work was to study the association between motivation and use of social networks and positive body image, considering differences by sex and age groups. The sample had 180 participants, 94 men (52.2 %) and 86 women (47.8 %), ages 18 to 65 years (M = 31.03; SD = 13.34). The instruments used were BAS-2 and a survey on social networks. Positive body image presented a negative association with two scales of motivation to use social networks. Positive body image and active use, on the one hand, and motivation to search and maintain social ties, on the other, showed a higher correlation in the group of women and digital natives, respectively.

Keywords: positive body image; social networks; motivation and types of use; sex; age

La imagen corporal positiva presenta una función protectora preeminente ante los medios de comunicación actuales, sin embargo, a la fecha no se cuenta con estudios que la vinculen con las redes sociales. El objetivo de este trabajo fue estudiar la asociación entre la motivación y usos de redes sociales y la imagen corporal positiva, considerando diferencias por sexo y grupos de edad. La muestra contó con 180 participantes, 94 varones (52.2 %) y 86 mujeres (47.8 %), edades de 18 a 65 años (M = 31.03; DE = 13.34). Los instrumentos utilizados fueron el BAS-2 y una encuesta sobre redes sociales. La imagen corporal positiva presentó asociación negativa con dos escalas de la motivación para usar redes sociales. La imagen corporal positiva y uso activo, por un lado, y la motivación de búsqueda y mantenimiento de vínculos sociales, por otro, presentaron mayor correlación en el grupo de mujeres y nativos digitales, respectivamente.

Palabras clave: imagen corporal positiva; redes sociales; motivación y tipos de uso; sexo; edad

A imagem corporal positiva tem uma função protetora de destaque na mídia atual; no entanto, até o momento, não existem estudos vinculando-a às redes sociais. O objetivo deste trabalho foi estudar a associação entre motivação e uso de redes sociais e imagem corporal positiva, considerando diferenças por sexo e grupos etários. A amostra contou com 180 participantes, 94 homens (52,2 %) e 86 mulheres (47,8 %), com idades entre 18 e 65 anos (M = 31,03; DP = 13,34). Os instrumentos utilizados foram o BAS-2 e uma pesquisa nas redes sociais. A imagem corporal positiva apresentou associação negativa com duas escalas de motivação para o uso das redes sociais. Imagem corporal positiva e uso ativo, por um lado, e motivação para buscar e manter laços sociais, por outro, mostraram maior correlação no grupo de mulheres e nativos digitais, respectivamente.

Palavras-chave: imagem corporal positiva; redes sociais; motivação e tipos de uso; sexo; idade

The most recent studies on body image tend to separate it between its positive and negative components, banishing the conception that the absence of body dissatisfaction implies the presence of well-being. These positive components, called positive body image, are defined as the love and respect that people feel for their body as it is, regardless of visualizing aspects that they want to change (Guest et al., 2019). Likewise, one of the central functions of positive body image is to dismiss surrounding information that would become harmful to the body (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015a).

Meanwhile, the negative influence of the media in relation to body image is well known (Thompson & Heinberg, 1999). Studies focused on classic media, such as radio or television, show negative and moderate associations between the internalization of the ideals disseminated in these media and positive body image (Swami, 2009; Swami & Toveé, 2009). On the other hand, the most current media, such as social networks, show a greater influence, as a result of their direct implications in the daily lives of their users (Orihuela, 2008).

So far, the vast majority of studies have focused on the relationship between more classical aspects of body image, based on its negative components, and social networks. These investigations have found a positive association between body dissatisfaction and the frequency of checking statuses on social networks (De Vries, Peter, Nikken, & de Graaf, 2014; Fardouly & Vartanian, 2015; Ferguson, Muñoz, Garza, & Galindo, 2014), a positive correlation between the presence of eating disorder symptoms and negative feedback received on social networks or time spent on social networks (Hummel & Smith, 2015; Mabe, Forney, & Keel, 2014), and a positive association between constant appearance monitoring and time spent on social networks (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2012).

Even so, works such as those by Gerson, Plagnol and Corr (2017) and Hollenbaugh and Ferris (2014) raise a strong criticism of the methodology of studies such as those previously mentioned. The central point would be that variables such as time spent, or frequency of use, on social networks would present associations that are too general. Instead, these researchers propose to study the motivations and types of use that users give to social networks, since this conditions the information with which they interact and the ways in which it is consumed.

In this regard, there are so far no studies that analyze the relationship between positive body image and the motivation and types of use of social networks. Some authors include in their studies what, in terms of this work, could be interpreted as motivations and types of social network use. Even so, these studies resort to the classic conceptualization of the body satisfaction/dissatisfaction pair; concluding that body satisfaction presents a negative association with motivation sustained in the use of social networks as a socialization arena and intense active use (Cohen, Newton-John, & Slater, 2018; Kim & Chock, 2015; McLean, Paxton, Wetheim, & Masters, 2015).

Of the few studies that include positive body image in their designs, they do so to investigate its influence on users' behaviors around photographs. In this sense, positive body image would function in a protective manner against body dissatisfaction resulting from viewing images, in social networks such as Facebook, of more attractive peers (Wang, Fardouly, Vartanian, & Lei, 2019). Likewise, there is evidence that high levels of positive body image are associated with lower levels of concern about the appearance presented, and the opinion of others about it, when posting selfies on social networks (Veldhuis, Alleva, Bij de Vaate, Keijer, & Konijn, 2018).

In summary, positive body image has virtually no research on its relationship with social networks. This being the case, it is unknown whether the already known dynamics between positive body image and traditional media are replicated in social networks, moreover, whether novel associations are present. Also, variables such as gender and age have not been studied in relation to the relationship between positive body image and the motivations and types of social network use. Even so, differences can be expected based on some general considerations.

He, Sun, Zickgraf, Lin and Fan (2020), in a meta-analysis, found that males tend to have higher levels of positive body image than females. From the systematic review by Mills, Musto, Williams, and Tiggemann (2018), it is concluded that few studies include the difference by sex around social networks and body image, of which all focus on body dissatisfaction. Even so, it can be highlighted that, comparatively, females presented greater body dissatisfaction than males when using Facebook. On the other hand, the difference between men and women in relation to digital communication seems to be qualitative. Guadagno, Muscanell, Okdie, Burke and Ward (2011) point out that both sexes repeat, in the digital space, the hegemonic role expectations of their societies: women focused on socialization and men dedicated to achievement.

As for age, despite being a universally reported variable, there are no studies that use it to analyze differences in social networks, either in relation to positive body image or to a more classical view of body image. Even so, and in general, it can be noted that there is some consensus that positive body image increases over time, i.e., the older the age, the higher levels of positive body image are expected, although this would only apply to women (Agustus-Horvath & Tylka, 2011; Tiggemann & McCourt, 2013).

Likewise, this study opted for the distinction between migrants, born before the 1990s who had to adapt to new technologies, and digital natives, who would have a natural link with social networks and technological advances (Hernández and Hernández, Ramírez-Martinell, & Cassany, 2014). At the same time, to date there are no studies of social networks and body image that include digital migrants. Even so, Saiphoo and Vahedi (2019) point out that increasing age is associated with a lower use of social networks and a lower association with body dissatisfaction.

The present work aims to analyze the association between positive body image and the use of social networks in Argentine adult population. Likewise, and as a second objective, we seek to analyze the specific differences in the associations between the aforementioned variables by sex and age group.

In accordance with previous studies, three hypotheses were proposed for this study. First, that positive body image is negatively associated with motivation based on seeking attention from others or as a means of entertainment (Pastime and Exhibition scale), with motivation based on seeking and maintaining social ties (Virtual Community and Companionship scale), with a type of use centered on interaction with other users (Active-Social scale) and a type of use centered on passive viewing of content (Passive scale).

The second hypothesis holds that the male group presents a higher correlation between positive body image and motivation based on seeking attention from others or as a means of entertainment (Pastime and Exhibition scale), motivation based on seeking and maintaining social ties (Virtual Community and Companionship scale) and a type of use centered on passive viewing of content (Passive scale), than the female group.

Finally, the third hypothesis expresses that the group of digital natives present a higher correlation between positive body image and motivation based on the search for and maintenance of social ties (Virtual Community and Companionship scale), with a type of use centered on interaction with other users (Active-Social scale) and the creation of content without interacting with other users (Active-Non-Social scale), than digital migrants.

Method

Sample

Sampling was non-probabilistic and participation was voluntary and anonymous. Regarding the inclusion criteria, the subjects were adults of both sexes. Likewise, in order to examine the general adult population (considering that most studies on the subject only focus on young adults) and to be able to make comparisons by age group, participants had to be between 18 and 65 years of age, whether or not they were users of social networks. The total sample consisted of 180 participants, 94 males (52.2 %) and 86 females (47.8 %). The age range ranged from 18 to 65 years (M = 31.03; SD = 13.34), with 109 (60.4%) being between 18 and 30 years old and the remaining 71 (39.4 %) between 31 and 65 years old. Of the total number of participants, 56 (31.1 %) reported living in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and 124 (68.9 %) reported living in Greater Buenos Aires, while 12 (6.66 %) reported that they did not use social networks, 3 males (1.66 %) and 9 females (5 %).

Instruments

The Body Appreciation Scale-2 (BAS-2; Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015b) is an instrument designed to provide psychometric support for the evaluation of positive body image in three dimensions: acceptance of the body, respect for the body, and protection of the body from the influence of media body image. It is composed of 10 items with a Likert-type response option with five options, ranging from Never (1 point) to Always (5 points). The scores are obtained by generating an average ranging from 1 to 5, the higher the score, the higher the positive body image. The local adaptation showed excellent internal consistency (α = .93), good factorial validity and convergent with constructs such as body dissatisfaction or sociocultural attitudes towards appearance (Góngora, Cruz, Mebarak, & Thornborrow, 2020).

Survey on social networks, composed of two sections based on the Motivations and use of Facebook (Hollenbaugh & Ferris, 2014) and The Passive Active Measure (PAUM; Gerson et al., 2017). From the aforementioned surveys, the wording of the items is modified in order to cover all the respondent's social networks and those referring exclusively to the social network Facebook are deleted. Also, given that previous studies have found that information seeking is a frequent behavior in the Argentine adult population (Castro Solano & Lupano Perugini, 2019), four items were added in relation to this behavior (e.g., “To find out about news, daily events, etc.”). The first section of the survey investigates the reasons why the subjects use the different social networks of which they are users, it presents three scales: Hobby and Exhibitionism, which implies the use of social networks as a means of entertainment or to capture the attention of others; Virtual Community and Companionship, in this case the motivation is focused on creating bonds and the use of social networks as a means to sustain them; Maintenance of Social Relationships and Search for Information, the scale reflects the motivation to use social networks as a means to collect and disseminate information both at the bonding and social level. It consists of 30 items, 29 corresponding to the three scales and one that allows the subject to describe another possible use of social networks; it is answered using a five-option Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1 point) to Strongly Agree (5 points) and is scored by generating an average for each of the three scales. Likewise, the second section evaluates the type of use given by the subjects to social networks, dividing this into three scales: Active-Social use, which involves interactions with other people; active-non-social use, which involves the creation of content, but not direct interaction with others; and Passive use, which involves viewing content without direct interaction. It presents 18 items, one of which allows the subject to describe another possible use of social networks. It is answered using a Likert scale ranging from Never (0 %, 1 point) to Very frequent (100 %, 5 points) and an average is evaluated for each scale.

Procedure

The sample collection was organized in both public and private spaces, being carried out in groups of between 10 and 15 people, with an administration time of between 35 and 45 minutes. By means of informed consent, it was explained to the participants that the protocol was anonymous, voluntary and would not be returned, and it was made clear to them that they could stop answering at any time they wished. This research complied with the international ethical standards established by the American Psychological Association. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.

Results

Correlations of positive body image and the social networking survey

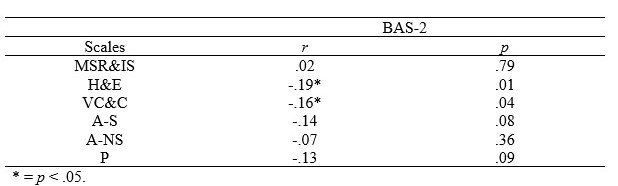

In order to assess the relationship between positive body image and the scales Social Relationship Maintenance and Information Seeking, Pastime and Exhibitionism, Virtual Community and Companionship, Active-Social, Active-Non-Social and Passive, a Pearson's r relationship coefficient calculation was performed (Table 1). Two significant and low negative correlations were found between positive body image and the Hobby and Exhibitionism (r = -.19, p = .01) and Virtual Community and Companionship (r = -.16, p = .04) scales. The results show that the tendency to use social networks as a means of entertainment or to capture the attention of others, as well as the use focused on the creation or maintenance of social ties, present a weak negative association with positive body image.

Table 1: Correlation between positive body image and social networking survey

Note: MSR&IS = Maintenance of Social Relationships and Information Seeking. H&E = Hobby and Exhibitionism. VC&C = Virtual Community and Companionship. A-S = Active-Social. A-NS = Active-Non-Social. P = Passive.

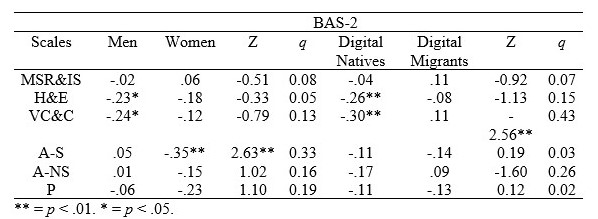

Sex and age group differences in correlations between positive body image and the social network survey Pearson's r correlation coefficient, then Fisher's Z and Cohen's q coefficient of the effect size of the correlations’ differences were calculated in order to analyze whether there were differences by sex, as well as between the digital native’s group (aged 18 to 30 years) and the digital migrant’s group (aged 31 to 65 years) (see Table 2).

We found statistically significant negative weak correlations for the male group between Positive Body Image and the Hobby and Exhibitionism (r = -.23, p = .03) and Virtual Community and Companionship (r = -.24, p = .02) scales. That is, for the male group, positive body image was negatively associated with the use of social networks as a recreational activity, an overexposure of self, and the search for and maintenance of affective bonds. Likewise, in the female group, a weak negative correlation was found between Positive Body Image and Active-Social type of use (r = -.35, p = .00). In this regard, in the group of women, a negative association was found between positive body image and the tendency to use social networks actively to contact and dialogue with other users.

When evaluating the differences between males and females, using Fisher's Z test, a statistically significant difference of a moderate magnitude was found in the Active-Social scale (Z = 2.63, p = .00, q = 0.33). Thus, the group of female participants presented a greater inverse correlation, than the group of males, between the use of social networks more intensely and assiduously and positive body image.

On the other hand, statistically significant negative weak correlations were found for the group of digital natives in the Hobby and Exhibition (r = -.26, p = .00) and Virtual Community and Companionship (r = -.30, p = .00) and positive body image scales. Consequently, the tendency of the group of digital natives to use social networks as a means of self-exposure and recreation, as well as for seeking and sustaining social ties, presented a weak negative association with their positive body image.

Meanwhile, when addressing the difference between migrants and digital natives, two statistically significant differences were found. The first in the Virtual Community and Companionship scale, with a moderate magnitude (Z = -2.56, p = .00, q = 0.43). In this regard, the group of digital natives showed higher correlations, than digital migrants, between positive body image and the use of social networks for the search for and maintenance of social ties.

Table 2: Magnitude of effect of differences in correlations between positive body image and social network survey

Note: MSR&IS = Maintenance of Social Relationships and Information Seeking. H&E = Hobby and Exhibitionism. VC&C = Virtual Community and Companionship. A-S = Active-Social. A-NS = Active-Non-Social. P = Passive.

Discussion

In relation to the first hypothesis, it can be noted that, although mostly negative, only the Hobby and Exhibition and Virtual Community and Companionship scales were statistically significant in their association with positive body image. A likely explanation for these associations is that they relate to behaviors with negative effects on positive self-image. In this sense, the results are consistent with other studies showing negative effects on body image of behaviors such as exhibitionism on social networks (Hogue & Mills, 2019; Mills et al., 2018), intense prosocial uses (Fardouly, Willburger, & Vartanian, 2017) or simple overexposure to social network content (Tamplin, McLean & Paxton, 2018).

The second hypothesis compared four associations around the sex of the participants in relation to positive body image. Of these, the Passive scale did not present a statistically significant association. Hobby and Exhibition and Virtual Community and Companionship were significant negative and low in males only, although the Active-Social scale did show a significant difference between both sexes, with females presenting a higher negative correlation. These results can be related to the study by Ferenczi, Marshall and Bejanyan (2017) in which women who were more active on Facebook tended to establish unfavorable social comparisons for their appearance, which in turn would be related to a lower level of Positive Body Image.

In relation to the third hypothesis, statistically significant results were found for two types of social network use motivation. Digital natives showed a higher negative correlation between positive body image and the use of social networks as a hobby or means of exposure, but this difference was not statistically significant with digital migrants. Meanwhile, digital natives presented a higher, and negative, correlation between positive body image and the use of social networks to search for and maintain social ties. Unlike digital migrants, social networks are the most relevant communication medium for digital natives and through which they legitimize the identity constructions they make of themselves (Cáceres, Ruiz San Román, & Brändle, 2009, 2011; Manago, Graham, Greenfield, & Salimka, 2008). Likewise, and comparatively, social networks present greater negative effects on body image than more traditional media (Fardouly, Pinkus, & Vartanian., 2017), in addition to which they present greater involvement in the personal lives of their users (Orihuela, 2008). Then, although they were low, a possible explanation for the higher correlations in digital natives would be based on the fact that the greater predominance of social networks would be associated with a greater impact on their users, which would enhance the negative effects of this medium on positive body image.

One of the main limitations of this study is its non-probabilistic sampling. In turn, there were few participants and the distributions of the subgroups were not homogeneous. Likewise, it cannot be ignored that, particularly the survey on social networks, being self-report questionnaires, are not exempt from social desirability on the part of the participants.

Regarding future lines of study, further study is required on how exhibitionism, as well as intense prosocial activity, in social networks affects positive body image. On the other hand, the inclusion of positive body image as a protective factor in prevention programs for body image-related problems stands out as a recent development (Piran, 2015). In this regard, it would be advisable for new programs and interventions to contemplate the link between social networks and positive body image. For example, interventions aimed at decreasing behaviors such as self-exposure or an intense social use of social networks should be included. This in turn allows us to point out another major difficulty within this field. Current intervention programs implicitly presuppose the same mode of production and dissemination of ideals about appearance both in the classic media and in social networks. For example, if we analyze the Media Smart prevention program (Wilksch et al., 2017) we find that, despite being one of the few that includes social networks (specifically Facebook) in its protocol, it assesses the internalization of ideals about appearance with the Sataq-3 (Thompson, Van Den Berg, Roehring, Guarda, & Heinberg, 2004). Both the named instrument, as well as its more recent version Sataq-4 (Schaefer et al., 2015), prove inadequate to specifically assess social network dynamics around ideals about appearance. In the first instance, the Sataq-3 inquires only about classic media such as magazines, television and cinema, relegating younger populations who value modern media more highly to the detriment of traditional media (Cáceres et al., 2009, 2011). For its part, the Sataq-4 attempts to include social networks in its last four items, but it does so in an overlapping manner along with other media, which prevents a specific evaluation of the impact of social networks on the formation of ideals regarding appearance. All this enables us to think of a last possible line of study. It would be advisable to take the already existing instruments for traditional media and adapt them to take into account the specificities and dynamics of social networks or, if this generates greater difficulties, to design a new instrument specifically for social networks.

Finally, this study presents two central contributions. First, it examines the associations of positive body image in a field of wide relevance and validity such as 2.0 networks. It also explores an alternative model, within the study of computer-mediated communication, which focuses on the types of use and motivations of users in relation to their social networks. On the other hand, first evidence is found that the group of younger adults, as well as the female group, are the ones who show greater negative associations between social networks and their positive body image. Likewise, the present work is valuable in order to delimit which motivations and types of social network use are noteworthy in their link with positive body image. In summary, this work contributes to the study of positive body image in a field that is practically unexplored, particularly in the Argentine context.

REFERENCES

Agustus-Horvath, C. L., & Tylka, T. L. (2011). The Acceptance Model of Intuitive Eating: A Comparison of Women in Emerging Adulthood, Early Adulthood, and Middle Adulthood. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(1), 110-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022129 [ Links ]

Cáceres, M. D., Ruiz San Román, J. A., & Brändle, G. (2009). Comunicación interpersonal y vida cotidiana: La presentación de la identidad de los jóvenes en Internet. CIC Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 11, 213-231. [ Links ]

Cáceres, M. D., Ruiz San Román, J. A., & Brändle, G. (2011). El uso de la televisión en un contexto multipantallas: viejas prácticas en nuevos medios. Análisis, 43, 21-44. [ Links ]

Castro Solano, A., & Lupano Perugini, M. L. (2019). Perfiles diferenciales de usuarios de internet, factores de personalidad, rasgos positivos, síntomas psicopatológicos y satisfacción con la vida. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica, 4(53), 79-90. https://doi.org/10.21865/RIDEP53.4.06 [ Links ]

Cohen, R., Newto-John, T., & Slater, A. (2018). ‘Selfie’-objetivation: the role of selfies in self-objectification and disordered eating in Young women. Computers in Human Behavior, 79, 68-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.027 [ Links ]

de Vries, D. A., Peter, J., Nikken, P., & de Graaf, H. (2014). The Effect of Social Network Site Use on Appearance Investment and Desire for Cosmetic Surgery Among Adolescent Boys and Girls. Sex Roles, 71(9-10), 283-295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0412-6 [ Links ]

Fardouly, J., Pinkus, R. T., & Vartanian, L. R. (2017). The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women’s everyday lives. Body Image, 20, 31-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002 [ Links ]

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12(1), 82-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004 [ Links ]

Fardouly, J., Willburger, B. K., & Vartanian, L. (2017). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objetification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media & Society, 20(4), 1380-1395. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1461444817694499 [ Links ]

Ferenczi, N., Marshall, T. C. & Bejanyan, K. (2017). Are sex differences in antisocial and prosocial Facebook use explained by narcissism and relational self-constructual? Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 25-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.033 [ Links ]

Ferguson, C. J., Muñoz, M. E., Garza, A., & Galindo, M. (2014). Concurrent and Prospective Analyses of Peer, Television and Social Media Influences on Body Dissatisfaction, Eating Disorder Symptoms and Life Satisfaction in Adolescent Girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9898-9 [ Links ]

Gerson, J., Plagnol, A. C., & Corr, P. J. (2017). Passive and Active Facebook Use Measure (PAUM): Validation and relationship to the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.034 [ Links ]

Góngora, V. C., Cruz, V., Mebarak, M. R., & Thornborrow, T. (2020). Assessing the measurement invariance of a Latin-American Spanish translation of the Body Appreciation Scale-2 in Mexican, Argentinean, and Colombian adolescents. Body Image, 32, 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.01.004 [ Links ]

Guest, E., Bruna, C., Williamson, H., Meyrick, J., Halliwell, E., & Harcourt, D. (2019). The effectiveness of interventions aiming to promote positive body image in adults: A systematic review. Body Image, 30, 10-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.04.002 [ Links ]

Guadagno, R. E., Muscanell, N. L., Okdie, B. M., Burk, N. M., & Ward, T. B. (2011). Even in virtual environments women shop and men build: A social role perspective on Second Life. Computer in Human Behavior, 27, 304-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.08.008 [ Links ]

Hernández y Hernández, D., Ramírez-Martinell, A., & Cassany, D. (2014). Categorización de los usuarios de sistemas digitales. Revista de medios y educación¸ 44, 113-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2014.i44.08 [ Links ]

He, J., Sun, S., Zickgraf, H. F, Lin, Z., & Fan, X. (2020). Meta-analysis of gender differences in body appreciation. Body Image, 33, 90-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.011 [ Links ]

Hogue, J. V., & Mills, J. S. (2019). The effects of active social media engagement with peer son body image in young women. Body Image, 28, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.11.002 [ Links ]

Hollenbaugh, E. E., & Ferris, A. L. (2014). Facebook self-disclosure: Examining the role of traits, social cohesion, and motives. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 50-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.055 [ Links ]

Hummel, A. C., & Smith, A. R. (2015). Ask and you shall receive: Desire and receipt of feedback via Facebook predicts disordered eating concerns. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(4), 436-442. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22336 [ Links ]

Kim, J. W., & Chock, T. M. (2015). Body image 2.0: Associations between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Computer in Human Behavior, 48, 331-339. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.009 [ Links ]

Mabe, A. G., Forney, K. J., & Keel, P. K. (2014). Do you “like” my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(5), 516-523. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22254 [ Links ]

Manago, A. M., Graham, M. B., Greenfield, P. M. & Salimka, G. (2008). Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29, 446-458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.07.0010 [ Links ]

McLean, S. A., Paxton, S. J., Wetheim, E. H., & Masters, J. (2015). Photoshopping the selfie: Self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. Eating Disorders, 48, 1132-1140. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22449 [ Links ]

Mills, J. S., Musto, S., Williams, L., & Tiggemann, M. (2018). “Selfie” harm: Effects on mood and body image in young women. Body Image, 27, 86-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.007 [ Links ]

Orihuela, J. L. (2008). Internet: la hora de las redes sociales. Nueva Revista de Política, Cultura y Arte, 119, 57-62. [ Links ]

Piran, N. (2015). New possibilities in the prevention of eating disorders: The introduction of positive body image measures. Body Image, 14, 247-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.03.008 [ Links ]

Saiphoo, A. N., & Vahedi, Z. (2019). A meta-Analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 259-275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028 [ Links ]

Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Thompson, J. K., Dedrick, R. F., Heinberg, L. J., Calogero, R. M., … Swami, V. (2015). Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037917 [ Links ]

Swami, V. (2009). Body appreciation, media influence, and weight status predict consideration of cosmetic surgery among female undergraduates. Body Image, 6(4), 315-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.001 [ Links ]

Swami, V. & Tovée, M. J. (2009). A comparison of actual-ideal weight discrepancy, body appreciation, and media influence between street-dancers and non-dancers. Body Image, 6(1), 304-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.006 [ Links ]

Tamplin, N. C., McLean, S. A. & Paxton, S. J. (2018). Social media literacy protects against the negative impact of exposure to appearance ideal social media images in Young adult women but not men. Body Image, 26, 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.05.003 [ Links ]

Thompson, J. K., & Heinberg, L. J. (1999). The media´s Influence on Body Image Disturbance and Eating Disorders : We’ve Reviled Them, Now Can We Rehabilitate Them? Journal of Social Issues, 15(2), 339-353. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00119 [ Links ]

Thompson, J. K., Van Den Berg, P., Roehring, M., Guarda, A. S. & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10257 [ Links ]

Tiggemann, M., & McCourt, A. (2013). Body appreciation in adult women: relationships with age and body satisfaction. Body Image, 10, 624-627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.07.003 [ Links ]

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015a). What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundation and construct definition. Body Image , 14, 118-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.001 [ Links ]

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015b). The Body Appreciation Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image , 12, 53-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006 [ Links ]

Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2012). Understanding Sexual Objectification: A Comprehensive Approach Toward Media Exposure and Girls’ Internalization of Beauty Ideals, Self-Objectification, and Body Surveillance. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 869-887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01667.x [ Links ]

Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Bij de Vaate, A. J. D., Keijer, M. G., & Konijn, E. A. (2018). Me, my selfie, and I: the relations between selfie behaviors, body image, self-objectification, and self-esteem in young women. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000206 [ Links ]

Wang, Y., Fardouly, J., Vartanian, L. R., & Lei, L. (2019). Selfie-viewing and facial dissatisfaction among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of general attractiveness internalization and body appreciation. Body Image, 30, 35-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.05.001 [ Links ]

Wilksch, S. M., O’Shea, A., Taylor, C. B., Wilfley, D., Jacobi, C., & Wade, T. D. (2017). Online prevention disordered eating in at-risk young-adult women: A two-country pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 48(12), 2034-2044. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003567 [ Links ]

Correspondence: Vanesa Carina Góngora. Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet), Argentina. E-mail: vgongo1@palermo.edu

How to cite: Berri, P. A. & Góngora, V. C. (2021). Positive body image and social networks in adult population of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(1), e-2398. doi: ttps://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2398

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M. P. has contributed in a, b, c, d and e.

Received: July 02, 2020; Accepted: February 03, 2021

texto em

texto em