Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.1 Montevideo jun. 2021 Epub 01-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2159

Original Articles

ZICAP II Scale: Parental Alienation Assessment in 9 to 15 years-old children of separated parents in Chile

1 Universidad del BíoBío. Chile. nzicavo@ubiobio.cl.

2 Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Argentina.

The aim of this research was to build a valid and reliable instrument to evaluate Parental Alienation (PA) in Chilean kids, between 9 and 15 years. This project started by the need of an instrument to collect evidence of child/parent bond obstruction, a source of severe intra-family child abuse observed in conflictive divorce situations. The items were constructed based on theoretical conceptualization of PA and submitted to expert’s judges who agreed to review and enriched them, to be later submitted to statistical analysis and successive adjustments. The final outcome consists of 29 items, 8 components and two dimensions instrument (Dimension I: Alpha value of .777, Dimension II: Alpha value of .884). This scale was applied to a sample of 1.181 children from 9 to 15 years-old with separated parents, of the south-central regions of Chile. Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed on the theoretical structure previously proposed, observing acceptable adjustment values.

Keywords: parental alienation; psychometric properties; scale; child abuse

El objetivo de esta investigación fue construir un instrumento para evaluar Alienación Parental (AP) en niños y adolescentes chilenos, entre 9 y 15 años. Se confeccionó una herramienta para recoger evidencias de obstrucción al vínculo hijo/padre, lo que constituye maltrato infantil intrafamiliar grave, observado en procesos de divorcios conflictivos. Los ítems fueron construidos a partir de la conceptualización teórica de AP y se sometieron a consideración de jueces expertos quienes los enriquecieron, después de lo cual fueron sometidos a análisis estadísticos y ajustes sucesivos. De dicho proceso se obtuvo un instrumento de 29 ítems, 8 componentes y dos dimensiones (Dimensión I Alfa de Cronbach de .777, Dimensión II con un Alfa de Cronbach de .884). Esta escala se aplicó a 1181 hijos de padres separados, de 9 a 15 años, del centro sur de Chile. Se realizó el Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio sobre la estructura teórica previamente propuesta observándose valores de ajuste aceptables.

Palabras clave: alienación parental; propiedades psicométricas; escala; maltrato infantil

O objetivo desta pesquisa foi construir um instrumento para avaliar a Alienação Parental (AP) em crianças e adolescentes chilenos, entre 9 e 15 anos. Foi criada uma ferramenta para coletar evidências de obstrução do vínculo filho / pai, que constitui maltrato infantil intrafamiliar grave, observado em processos de divórcio conflituoso. Os itens foram construídos a partir da conceituação teórica da AP e foram submetidos à consideração de juízes especialistas que os enriqueceram, em seguida foram submetidos a análises estatísticas e ajustes sucessivos. A partir desse processo, foi obtido um instrumento com 29 itens, 8 componentes e duas dimensões (Dimensão I, Alfa de Cronbach de .777, Dimensão II com Alfa de Cronbach de .884). Essa escala foi aplicada a 1181 filhos de pais separados, de 9 a 15 anos, do centro-sul do Chile. A Análise Fatorial Confirmatória foi realizada sobre a estrutura teórica proposta previamente, observando-se valores de ajuste aceitáveis.

Palavras-chave: alienação parental; propriedades psicométricas; escala; maltrato infantil

Traditional family has given way to new structures with different relationship styles, conditioned by the women’s increasing economic emancipation and the progressive involvement of men in the upbringing of their children and housework. However, cultural, social and legal practices indicate that, in the event of divorce or marital separation, women generally must take charge of children’s care, upbringing and education, leaving the chance to both parents to continue with parental tasks (Lesme & Zicavo, 2014).

Family structure changes due to divorce situation and one of the parents is usually left in an asymmetrical, peripheral situation and oblivious to the dynamics in which he/she previously was involved, threatening his/her parental role, the consequence is a relational impairment with his/her children who lose a significant identity reference, being possible the development of many mental disorders, ranging from an adaptation disorder to a major depressive disorder (Bernet, Wamboldt & Narrow, 2016). Faced with a highly conflictive divorce, male parental distance is normalized by naturalizing the situations that impede parental participation in raising their children (Harman, Biringen, Ratajack, Outland, & Kraus, 2016; Zander, 2012). In contentious divorce cases, male parental distance becomes normal and the obstruction of parental participation in the raising of their children seems natural. Additionally, parental alienation (PA) behaviors cause moral dilemmas in children who are asked to go against their values and beliefs - spying or keeping secrets - which has unpredictable consequences on child development (Baker & Verrocchio, 2016).

Moreover, those responsible for providing justice, must discern which of the parents is suitable for "staying" with children, often a complex decision and where both members of the parental couple are not always properly heard and considered (Bernet et al., 2016). Fathers and mothers initiate an endless battle, where the experts help to discern facts, such as truths and falsehoods, responsibilities, insults and misdeeds, among others, which are often so difficult to prove (Kelly & Johnston, 2001).

At present, researchers have not developed a valid instrument to demonstrate the presence of the PA process. There is not a specialized tool that help to discover and disclose the abuse that children and some adults are being subjected to during a highly conflictive divorce. Such is the final purpose of this work, to make visible the presence of the process of abuse and domestic violence through a scale that measures PA in an efficient way. In addition, unveil the impact on society like today’s, which has ceased to view divorce as a cause of pathologies and social dissolution. Divorce does not seem to be a problem, but the possibility that it may disrupt established family equilibrium, empowering some family members more than others, with the undesirable result of incorporating children into a dispute between adults that harms children, instead of protecting them and help them to grow.

Laws and conflictive divorce

The law on violence 20.066 (2005) in Chile, tries to regulate and sanction the acts of violence within the family; it is defined as:

“Any mistreatment that affects life, physical or psychological integrity of the person who has or has had the status of spouse of the aggressor or a live-in partnership with him; or who is a relative by consanguinity or affinity in a direct line or a collateral line up to the third degree, inclusive of the aggressor or the spouse or the current live-in partner. There will also be intra-family violence when the conduct aforementioned occurs between the parents of a common child, or falls on a minor, an elderly or a disabled person who is under the care or dependence of any of the family group members (Section 5. Law 20.066)”.

Some modifications were made on this law (law No 20.480) including femicide as a punishable violent act (2010) and the increase of sanctions; nevertheless, there are still areas of attention that have not been addressed in the field of intra-family violence, especially the one performed as relationship obstruction between children and parents after the couple´s divorce.

During 2013, the Law No 20.680 was approved, known as Dad´s Love Law, which introduces the principle of shared responsibility, by which both parents, living together or separately, will participate actively, equally and permanently in the parenting and education of their children (section 224 subsection 1º of the Civil Code); adding that the shared personal care stimulates the shared responsibility of both parents living separately, in the parenting and education of the children in common (section 225 subsection 2º of the Civil Code); decreasing the asymmetries in custody for children of separate parents and limiting the impediment of contact in high-conflict divorces; taking into account that when this kind of divorce takes place we observe the obstruction of one of the parents towards the other to relate with physical proximity and emotionally with their children, repeated disputes between the former spouses, usually witnessed by the children and at least one member of the parental couple presents the imminent need of winning and denigrating the other (Folberg & Milne, 2005; Zicavo, Celis, González, & Mercado, 2016).

The exercise of parenting and its obstruction during conflictive divorce situation (limitation, impediment or obstruction of contact of one of the parents with their children) are strongly conditioned by power relations, as an essential part of human interaction (Ponce, Arrieta, Jalile, & Guini, in Zicavo, 2016). Parental Alienation appears as the extreme result of these interaction conflicts. In this regard, R. Gardner proposes the concept of parental alienation syndrome (SAP). SAP appears as a disorder characterized by the set of symptoms that result from the process by which a parent transforms the consciousness of the children with the aim of preventing, hindering or destroying the ties to the other parent (Gardner, 1998). It occurs within the context of disputes related to the custody of children and its first manifestation is a smear campaign against one of the parents, consciously structured by the custodial parent and supported by the child, a campaign that lacks justification (Gardner, 1998). For the author, the intensity of the alienation process evidenced in children can be typologically differentiated into three gradually increasing levels: Mild, Moderate and Severe (this classification will be discussed later).

Critical perspectives related to Parental Alienation (PA)

The SAP is not fully accepted by the academic and scientific world, although it is widely referred in legal environments due to parental disputes in highly conflictive divorce processes. Besides, the use of “syndrome” concept does not elicit broad agreements since authors such as Bernet and Baker (2013), even sharing the background of Gardner's proposal, distance themselves from this definition.

The authors state:

“Our definition of AP is a mental condition in which a child, usually whose parents are involved in a high-conflict separation or divorce, strongly allies with one parent (the preferred parent) and rejects a relationship with the other parent (the alienated parent) without legitimate justification. PA presents abnormal and maladaptive behavior (refusal to have a relationship with a loving parent) that is driven by an abnormal mental state consisting in a false belief that the rejected parent is evil, dangerous, or unlovable (Bernet & Baker, 2013, p. 99).

The aforementioned authors suggest the reformulation of the Gardner’s alienation model, distancing themselves from the denomination of syndrome and proposing to assume the terms AP as a relational process, in which there would be strong setbacks, conflicts, between parents and children in the course of care and guardianship as they grow. They see with close conceptual identity the enunciations of Kelly and Johnston (2001) who define the alienation model with a scheme of infantile behaviors characterized by hatred, fear and unjustified and disproportionate rejection against the estranged father (Kelly & Jonhston, in Bernet & Baker, 2013). Such behaviors would not be a mental illness, rather they are evidence of a relational problem or dysfunctional family interaction (Bernet & Baker, 2013; Siracusano, Barone, Lisi, & Niolu, 2015).

Other authors, such as Moses and Townsend (2011), O'Donohue, Benuto and Bennett (2016), Pepiton, Alvis, Allen and Logid (2012), and Zirogiannis (2001), point out that there would not be enough empirical evidence for PAS to be a psychiatric diagnosis. Therefore, the situation characterized as parental alienation should not be included in the DSM and ICD classification manuals. On the other hand, Gardner's publications are questioned, since most were not published in peer-referenced journals and would be from his own publisher. Thus, his articles were not subjected to peer review, and, therefore, the works lack of scientific support in terms of their contribution (Moses & Townsend, 2011; Pepiton et al., 2012).

On the other hand, Walker, Brantley and Rigsbee, 2004 (in O'Donohue et al., 2016) argued that some children have separation anxiety when their parents are divorcing. Therefore, such "symptoms" of the child may also demonstrate his attempts to manage the stress of the family situation, regardless of the existence of mistreatment or child abuse promoted by one of his/her parents. In addition, they point out that such symptoms may also be the result of physical or sexual abuse (or neglect) that occurred before, which may have been one of the precipitating reasons for the conflictive divorce. This situation in itself generates unavoidable confusion and lack of scientific rigor in the diagnosis. To sum up, authors present a very detail set of arguments tending to demonstrate that there are no evidences that the characteristics involved in PAS constitute a valid syndrome (O'Donohue et al., 2016). Even so, they suggest that, even when PAS is not an acceptable diagnosis, it is necessary to understand that on many occasions some parents engage in specific behaviors in order to damage the child's relationship with the other parent.

The DSM and CIE classifications manuals not only have the due endorsement of the scientific community but are also guides in professional and academic work. However, they do not constitute in themselves a definitive and immutable truth. A look at the history related to what happened with homosexuality, ADHD, Autism, Schizophrenia, Neurosis, among others, contributes to understand this affirmation. These manuals are in constant revision, as they only suppose a certain consensus linked to a history moment and context. Therefore, the inclusion or exclusion of a term in the following edition has been part of a permanent debate that enriches the process since its evolution is obviously constant.

In this direction, in 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO), suggests the inclusion of Parental Alienation in the ICD-11. This inclusion does not constitute an independent diagnosis in itself but should be considered as a synonym or an index term for other specific diagnosis. This other diagnosis describes relationship problems between caregiver and child, and it is identified with the code QE52.0 (ICD-11, 2018), under the concept of Parenting. It involves problems associated with interpersonal relationships in childhood. The diagnosis describes substantial and sustained dissatisfaction in the relationship between the caregiver and the child, associated with significant disturbance in functioning. The index of terms specifies problems in the relationship between caregiver and child; problems between parents and children; problems between caregiver and child, between a parent and the previous caregiver; Parental Alienation; Parental estrangement (ICD-11, 2018). The mentions facts referred to parental alienation scientific consideration comes to settle an important part of the debate about its existence. However, its definition is perfectible, and the manuals must continue to change and adapt to new situations.

Finally, Aguilar (2006), Baker and Eichler (2016), Baker and Verrocchio, (2016), Bernet and Baker (2013), Bernet, Baker and Verocchio, (2015), Ferrari (1999), Gardner (1998), Ramírez (2011), Tejedor (2006) and Zicavo (2006), among others, affirm that there exist series of components that help to identify the process of parental alienation within the course of the conflictive breakup of the couple. These components are those that have guided the present research. We have named this elements Components for the identification of PA, and they consititue the theoretical basis in the construction of the ZICAP II Scale.

PA identification components

Evidences of the beginning of manipulative behaviour and malicious suggestion. This item includes behaviors of initial obstruction - direct or indirect - of the child contact with the non-custodial parent, carried out by the custodial parent. It usually occurs through clear and manifest manipulation of child's affects and loyalties. It is an initial suggestive process that attempts to turn children's loyalty to the father perceived as a victim of the misadjusted conjugality function of the other parent (Aguilar, 2006; Zicavo, 2010).

Use of time as an alienation strategy. When one of the parents is forced to be absent from the family dynamic for long periods of time, the other parent acquires great power in the formation and direction of child’s ideas, beliefs, affections and socialization processes. Systematic manipulation sustained over time is an effective and strong weapon in the hands of the alienator parent, turning the child to an active member of the smear campaign (Tejedor, 2006).

Difficulties in exercising right of access, visit or contact with the child. The custodial parent premeditatedly prevents or hinders the contact of the other parent with the child, scheduling other attractive or unavoidable activities at the very moment the contacted was accorded. Thus, the programmed contact is frustrated (Zicavo, 2010).

Judicial immersion processes. Alienating parents tend to use and abuse of judicial processes and the supervision of parent/child contacts. Additionally, they interrogate their children about what they have done, seen or heard during the contact with the other parent. Going further, AP describes them judicial episodes with the intention of influencing children’s ideas and beliefs, with the intention of manipulating them (Ramírez, 2011; Zicavo, 2006).

Insults and disapproval campaign. The child usually contributes to the alienating process actively with insults and contempt against the contact parent, as a result of the systematic action of the custodial parent to convert him into an ally in the battle raised to make the contact parent the solely responsible for the marital rupture (Aguilar, 2004; Baker & Verrocchio, 2016; Gardner, 1998). The child feels that he must take sides in the defense of the alienating parent as an act of alleged justice (Aguilar, 2004).

Spread hatred to the alienated parent’s environment. The alienated child not only shows antipathy and rejection of the absent parent (without any real justification for it) but to everything referred to he/she or any member of his/her family: grandparents, uncles, cousins, among others. It is important to note that before the beginning of the conflictive divorce, they had close and pleasant relationships that suddenly became dangerous and should be bewared or avoided (Aguilar, 2004).

Lack of feelings of guilt. The child refers to feel no guilt for the hatred experienced by his contact parent, because he/she deserves it. It constitutes an act of loyalty demanded by the custodial parent and subsequently incorporated as freely assumed conduct. This situation divides the world into good and bad, describing irreconcilable opposites without any remorse (Aguilar, 2004; Baker & Verrocchio, 2016).

Independent thinker phenomenon. The child affirms that the idea of rejecting the absent parent is exclusively his/her own and no one has influenced him/her, in clear allusion to a strong identification with the alienating parent (Gardner, 1998). It is indicative that the relational obstruction is installed and contributing to the uprooting of emotional ties (Baker & Verrocchio, 2016; Ferrari, 1999; Zicavo, 2006).

The presence of these components indicates a new form of child abuse that will have strong psychosocial effects on children's development. It reveals highly conflictive family processes that promote, as a result, the formation of dysfunctional relational patterns in people who later will reproduce - as a tendency - dysfunctional family ties or at least highly pathogenic conflict resolution mechanisms (see, for example Baker 2005). Even considering the aforementioned, since R. Gardner proposed the concept of parental alienation, cannot be set aside the discussions and controversies that it -as a syndrome- has generated in the scientific literature and clinical practice. In this sense, as we mentioned before, both the denomination of the phenomenon and its directionality and the involvement of each actor, among other dimensions, are currently being discussed (Kelly & Johnston, 2001 y Zander, 2012). Beyond the controversy, the description and characterization of the dysfunctional and alienating links during a difficult divorce acquire scientific and clinical relevance in terms of preventing harmful consequences of this relational conflictive situation (Cunha Gomide, Bedin Camargo, & Gonzales Fernandes, 2016).

PA Dimensions

The preliminary analysis report elaborated by a Chilean research group headed by one of the authors of the present paper, indicates that, in a sample of 257 children of separated parents (Zicavo, Celis, González, & Mercado, 2016), it was possible to organize theoretical components of PA into three dimensions. However, in successive adjustments derived from further measurements and statistical analysis, two dimensions were reached as central axes through which PA process is evidenced as a manifestation of child abuse and domestic violence. The mentioned dimensions are:

Dimension I. Alienating Behaviors: Capture or Emotional kidnapping. It is defined as any conscious action of manipulation and malicious suggestion, carried out with the aim of promoting child’s inescapable emotional commitments with the custodial parent and with whom the child lives (Zicavo et al., 2016). Suggestion operates affirming that only this parent can take care of him/her successfully, being the only one deserving of his/her affection and loyalty. Every other person is substitutable, leaving the emotional hijacking child prisoner of an emotional and malicious triangulation (Martínez, 2003; Zicavo et al., 2016). Children who present a higher level of vulnerability and helplessness in the presence of parental conflict are trapped or emotional kidnapped, becoming unconditional allies with the alienating person. This dimension includes the following components: Evidences of the beginning of manipulation and malicious suggestion; use of time as an alienation strategy; difficulties related with the right to visit and/or getting in contact with the child; Judicial immersion processes.

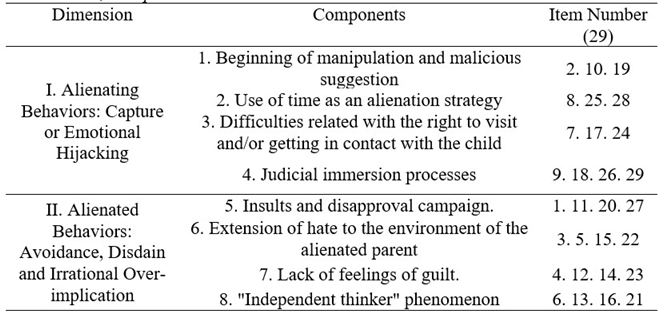

Dimension II. Alienated Behaviors: Avoidance, contempt and irrational over-involvement. In order to achieve a secure and balanced raising environment, the child must comply with the suggestive demands of loyalty, insults, avoidance and contempt for any person who does not have the approval and manifest affection of the custodial parent. It leads to a higher degree process of child aggression and implies that it has been involved in severe adult power struggle, derived from conflictive divorce (Zicavo et al., 2016). This dimension includes the following components: Insults and disapproval campaign; extension of hate to the environment of the alienated parent; lack of feelings of guilt; Independent thinker phenomenon. Table 1

Materials and Method

Parental Alienation Scale construction

Based on the theoretical assumptions above-mentioned, a list of multiple items was elaborated in order to evidence components of PA phenomenon. To minimize any participant`s defensive reactions, each component was written in different options, considering the possibility of identify and describe each PA component from different perspectives. Statements were presented as structured close-options items compounded by a 5-point Likert scale, graded according to intensity.

External expert judges. Their work consisted of selecting -from the 123 reagents initially constructed- the most pertinent to describe the PA. The experts could also include non-contemplated items or make modifications seeking to correspond between the theoretical and empirical elements of the study based on their experience. Next, a detailed record was prepared with those items that gathered the greatest consensus giving way to a preliminary instrument of 87 statements. To assess aspects of understanding and children’s’ time of responses, this questionnaire was preliminary applied to 13 students aged 9 to 15, from a subsidized private school in the city of Chillán, Chile, all children of separated parents. Testing the 87-item version, it was observed that children got tired quickly and sometimes did not adequately understand some statements, requiring support to answer. After a successive and careful 2-years study aimed to assess understanding and time of response, the less understood and statistically weaker items were eliminated, until arriving at a more solid instrument of 48 items. The scale was applied to a school children sample, independent of their family status (children of divorced parents or not). Authors considered this procedure as an adequate one related to this research step. Subsequent replications were decided to execute after this procedure, considering family status as a classifying attribute.

Pilot Study. A pilot study utilizing a 48-items version of the questionnaire was carried out. One hundred twenty-three questionnaires completed by children of separated parents were obtained from an initial sample of 338 students of a school from Chillán, Chile. Participants took around 10 to 12 minutes to reply the questionnaire, content was easy to understand. Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v. 22) program. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient analysis allowed researchers to eliminate those items that showed low item-component correlation. As a result of these analyses, a reliable 33-items version of the questionnaire was adopted. This version improved children’s access to the questionnaire and its understanding. A second pilot study, using the 33-items version of the questionnaire was applied to a 257 children sample from all regions of Chile. The researchers agreed to call the final version ZICAP Scale for children aged 9 to 15 years (Zicavo et al., 2016).

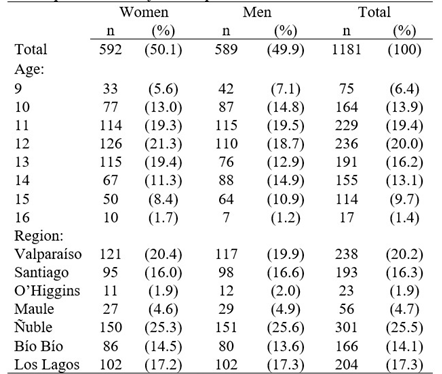

Definitive Application. Final version of ZICAP scale was applied to a sample of 3,385 persons from 7 different regions of Chile, belonging to different social and educational institutions. One thousand one hundred eighty-one questionnaires answered by children from divorced parents were obtained after the evaluation of the complete sample. This version of the scale was evaluated in different regions, included the central zone and a part of the south of Chile (see Table 2). Participants were included as a part of the sample intentionally, considering inclusion criteria and explicit informed consent.

Population and sample

In the present study, Chilean children and adolescents belonging to separated parents’ families, aged between 9 and 15 years were considered as the entire population. Selected sample was informal, intentional and non-probabilistic. Sample consisted of children of separated parents belonging to educational establishments or family mediation centers in regions V to XVI of Chile. The distribution by Regions of Chile as well as age and sex, can be seen below in Table 2, the final version of the scale was applied to the sample.

Ethical Considerations and Information Collection Process.

For the present research, ethical considerations were safeguarded by various procedures. On the one hand, the informed consent and review of research’s procedures were presented to the Ethics Committee of the reference University. Confidentiality of the data was ensured, which implied the protection of all personal information (França-Tarragó, 1996). Identity data of the participants were not requested, but of general reference, such as age, gender, family coexistence and marital status of the parents. Once the approval and acceptance of all the people involved in the process, including the parents or guardians of the children (knowledge, understanding and acceptance of the procedures), and of the children themselves, subsequent scale applications were conducted.

Results

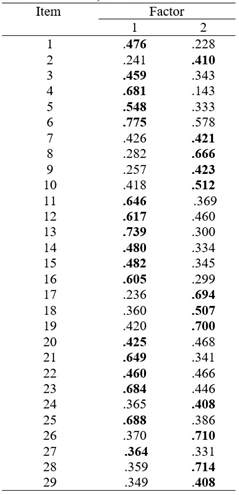

To conduct Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA) and subsequent Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA), the entire sample was randomly divided, considering 274 cases for the EFA and the remaining 907 cases for the CFA. To analyze whether the data met the requirements to apply this procedure, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Sample Adequacy measure was estimated, giving a value of 0.866, in addition, Bartlett's Sphericity test showed a result of χ² (df = 528) = 3596.87, p < .0001. On the other hand, to analyze normal distribution of the data, asymmetry and kurtosis values were estimated for each of the items. Only 7 of them approach the normal distribution and 26 items show a distribution that moves away from the normal curve.

Because data show conditions to allow a factor analysis, but no univariate or multivariate normality is observed, the unweighted least squares (ULS) procedure was used to perform the Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. As the factors were expected to be correlated in the AFE, the Oblimin Rotation Method was used. As an additional procedure, the anti-image correlation was estimated. Items with values below 0.8 were eliminated, obtaining a final instrument of 29 items. Following analyzes were performed considering this 29-items scale.

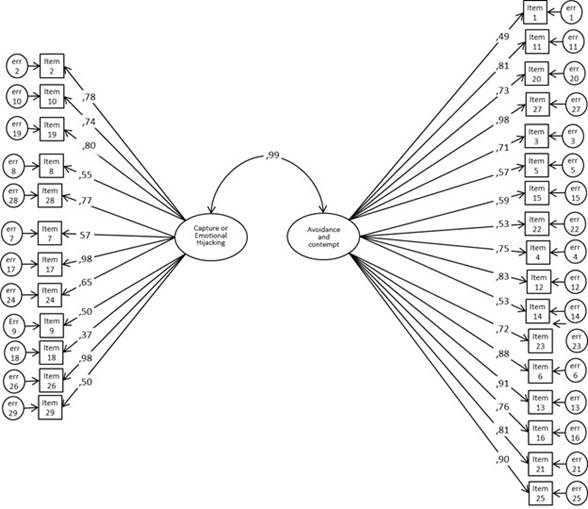

Theoretical two-dimensions solution was observed in the 29-itmes scale after the EFA application to the sample of 274 subjects (see table 3). Subsequently, the CFA was performed with the sample of 907 children whose results are shown in Figure 1. A good fit of the model is considered when χ² value is not significant; however, this test is sensitive to the sample size, tending to be significant in large sample size studies, similar to the present research (907 cases considered). Given this consideration, other goodness fit measures were considered. In these terms, χ² measure divided by degrees of freedom was considered acceptable when its results tend to be below to 5. Furthermore, GFI, AGFI y CFI indexes were obtained, considering that all of them must be greater than 0.95. RMSEA must be nearby or below to 0.05 (Escobedo, Hernández, Estebané & Martínez, 2016; Pérez & Medrano, 2010).

Confirmatory Factorial Analysis showed a significant result; χ² (df=376)= 979.06; p < .0001; χ²/df= 2.6; GFI= 0.969; AGFI= 0.964; CFI= 0.901; and RMSEA= 0.042. Therefore, it is possible to affirm that the tested model shows acceptable adjustment values with the data obtained from a sample of children of separated parents. Table 6

Reliability of each of the dimensions was analyzed using Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient. It is observed that, in Dimension I, Alienating Behaviors: Capture or Emotional Hijacking, the twelve items that compose it reached an alpha value of .777. This value would decrease when eliminating any of the items. Regarding Dimension II, Alienated Behaviors: Avoidance, Disdain and Irrational Over-implication, it indicates an alpha value of .884 for the seventeen items that compose it and this value would decrease when eliminating any of the items. Finally, the scales of the ZICAP II Scale, and of each of the dimensions, were constructed considering the averages and standard deviations observed in the sample, to estimate the standardized scores.

To obtain the standardized values, comparisons were made according to total values of the scale and of each of the dimensions according to sex and age and no significant differences are observed. Standardized values are calculated from the data of the entire sample. Finally, the scales of the ZICAP II Scale and of each dimension were constructed, considering the averages and standard deviations observed in the sample to estimate the standardized scores (average of 50; deviation 20).

Standardized scores lower than 90 are considered Absence of PA; scores equal to or greater than 90 and lower than 110 are considered Mild PA; standardized scores equal to or greater than 110 and lower than 130 are considered Moderate PA; and standardized scores equal to or greater than 130 are considered as Severe PA. Further discussion related to the above-mentioned grades classification will be found in the following section (Discussion and Conclusion).

Discussion and conclusions

Results of this study show that the ZICAP II Scale is suitable for measuring AP in children of separated parents aged 9 to 15 in southern central Chile. The validity of the results obtained with the ZICAP II Scale is supported by the theoretical construct underlying the studied phenomena. Creation, adaptation and validation of the various components that account for the strength of the instrument was protected in the present study.

Results obtained from the performed analysis indicate that the models processed by the Confirmatory Factor Analysis exhibit acceptable levels of adjustment, which confirms a theoretical factor structure divided into central dimensions and integrating components These results seem to be quite different from the original reported in the initial ZICAP scale for the evaluation of parental alienation: preliminary results. (Zicavo et al., 2016). The difference is to be found in the successive adjustments made from the statistical analyzes with the data obtained, which reaches a more parsimonious solution for addressing the theoretical proposal with a considerably more adjusted instrument, this time called the ZICAP II scale.

On the other hand, the statistical analysis of the structural matrix allows to confirm the validity of the initial theoretical proposal of two dimensions and 8 components. However, it is observed that items 7, 20 and 22 contribute similar charges in both factors. Therefore, it was decided to keep them in the factors assigned by the theory. This can be explained by the high correlation between the factors, since both are an inherent part of the AP process. The ZICAP II Scale showed adequate internal consistency, it is possible to affirm that it is a statistically reliable instrument.

In addition, it was observed that 17.6% of the cases show presence of AP, where the majority, 15.3% show a level of Mild AP, 1.9% Moderate AP and 0.4% of Severe PA. It is possible to suggest that higher levels of PA (moderate to severe) constitute evidences of explicit process of child abuse within family context. Present reports of PA presence seem to coincide with the line reported in the existing literature (Baker & Eichler, 2016; Baker & Verrocchio, 2016; Bernet & Baker, 2013; Bernet et al., 2015), indicating that these children manifest a high refusal to contact the parent with whom they do not live, as well as a very deteriorated image of him/her and his family environment whom they understand as completely bad and expendable in their life. This constitutes clear evidence of a violent act of aggression that causes deep emotional damage, a type of abuse and violence not yet contained in current domestic violence manuals.

Derived from the standardization of the ZICAP II Scale, the absence of AP in those low scores cases can be determined. This constitutes an element of transcendental importance, since it can allow specialists to have an efficient instrument to support with explicit evidence the objective veracity of their expertise in the clinical, social and legal field. In this way, results of the present study can contribute to minimizing possible expert-diagnostic mistakes that, otherwise, would have serious consequences for the psychological health of children and their families.

Cut-off point considered for PA grades is mainly statistical and there are still not solid clinical evidences to support such gradualness; however, some correspondence is assumed with the theoretical criteria detailed below:

Mild PA is a stage in which the paternal visits to the son pass with some intentional limitations. Although the conflict is limited, tension is present (Gardner, 2002). Sons usually exhibit independent thinking and emotionality, although he supports the alienating father promptly (Aguilar, 2006).

Moderate PA is a stage where conflicts and litigation between parents significantly increase (Gardner, 2002). The belittling campaign is accentuated and attempts to nullify the role or directly promote deparentalization (Ramírez, 2011). Affective ties with the non-custodial parent deteriorate progressively and profoundly while ties of manipulative emotional dependence with the custodial parent intensify.

Severe PA is a stage in which the discredit actions are extreme and continuous. Encounters with the non-custodial parent become impossible (Gardner, 2002). The child's hatred towards the alienated parent is extreme, and without guilt feelings (Aguilar, 2006). It is common for the alienated father to be prevented from keeping in contact with his/her children for months or years.

All the above evidences that the instrument is suitable for measuring PA in children aged 9 to 15 years in central southern Chile, children of separated parents. The ZICAP II Scale is a reliable measurement tool and constitutes, together with other works (Cunha et al., 2016), one of the first attempts in Latin America to empirically account for the phenomenon of parental alienation. Subsequent research could evaluate the applied potential of the tool developed in this study, focusing on the prevention of intrafamily violence during the difficult divorce process. The applied projections of the scale are, in this sense, very encouraging.

The ZICAP II Scale does not constitute itself a finished and closed instrument, it is plausible that in the near future it will still be improve. It requires other views and demands the incessant development from colleagues determined to banish child abuse in defense of the rights of children of separated parents.

Finally, it is important to note that this instrument aims to incorporate an approach based on the rights of children and adolescents (NNA) to consider, to take into account and also to recognize them as rights holders, not just as beneficiaries of the adult’s benevolence (Pautassi & Royo, 2012) hence the importance of developing instruments that consider their voices and testimony in highly conflictive divorces.

Recommendations and limitations

Although the scope of this work is supported by a 4-years long study of more than three thousand three hundred and eighty cases, of which one thousand one hundred and eighty-one were children of separated parents, in seven regions of central and southern Chile; it is important to validate the ZICAP II Scale in other cultural contexts and in different countries, contributing to its scale and standardization for other nations and populations. That is a pending task that could surely be addressed by colleagues interested in the subject.

In the same way, it is important to expand the studies to other age segments of the child population, validating the ZICAP II Scale and correcting possible distortions and biases that may be present in this study.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, J.M. (2004). S.A.P; Síndrome de Alienación Parental. España: Almuzara. [ Links ]

Aguilar, J.M. (2006). Con papá y con mamá. España: Almuzara . [ Links ]

Baker, A. (2005) The Long-Term Effects of Parental Alienation on Adult Children: A Qualitative Research Study. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 33, 289-302. [ Links ]

Baker, A. & Eichler, A. (2016). The Linkage Between Parental Alienation Behaviors and Child Alienation. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 57(7), 475-484. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2016.1220285 [ Links ]

Baker, A. & Verrocchio, M.C. (2016). Exposure to Parental Alienation and Subsequent Anxiety and Depression in Italian Adults. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 44(5), 255-271. doi: 10.1080/01926187.2016.1230480 [ Links ]

Bernet, W. & Baker, A. (2013). Parental alienation, DSM-5, and ICD-11: Response to critics. The journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 41(1), 98-104. [ Links ]

Bernet, W., Baker A. & Verrocchio M.C. (2015). Symptom Checklist-90-Revised Scores in Adult Children Exposed to Alienating Behaviors: An Italian Sample. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 60, 357-362. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12681 [ Links ]

Bernet, W., Wamboldt, M. Z., & Narrow, W. E. (2016). Child Affected by Parental Relationship Distress. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(7), 571-579. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.018 [ Links ]

CIE-11 (2018). Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades, OMS. Recuperado de https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f547677013 [ Links ]

Cunha Gomide, P.I., Bedin Camargo, E. & Gonzales Fernandes, M. (2016) Analysis of the Psychometric Properties of a Parental Alienation Scale. Paidéia, 26(65), 291-298. [ Links ]

Escobedo, M.T.; Hernández, J.; Estebané, V. & Martínez, G. (2016). Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales: características, fases, construcción, aplicación y resultados. Ciencia y Trabajo, 18(55), 16-22. [ Links ]

Ferrari, J.L. (1999). Ser padres en el tercer milenio. Argentina: Canto Rodado. [ Links ]

Folberg, J. & Milne, A. (2005). Divorcio como posible etapa del ciclo vital o divorcio destructivo. Revista de psicoterapia relacional e intervenciones sociales, 15, 18-24. [ Links ]

França-Tarragó, O. (1996). Ética para psicólogos. Introducción a la Psicoética. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer. [ Links ]

Gardner, R. (1998). The Parental Alienation Syndrome (2nd ed.). Cresskill, New Jersey: Creative Therapeutics. [ Links ]

Gardner, R. (2002). Denial of The Parental Alienation Syndrome Also Harms Women. American Journal of Family Therapy, 30(3), 191-202. doi: 10.1080/019261802753577520 [ Links ]

Harman, J.J., Biringen, Z., Ratajack, E.M., Outland, P.L. & Kraus, A. (2016). Parents Behaving Badly: Gender Biases in the Perception of Parental Alienating Behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(7), 866-874. doi: 10.1037/fam0000232 [ Links ]

Kelly, J.B. & Johnston, J.R. (2001). The Alienated Child. A Reformulation of Parental Alienation Syndrome. Family Court Review, 39(3), 249-266. doi: 10.1111/j.174-1617.2001.tb00609.x [ Links ]

Lesme, D. & Zicavo, N. (2014). Hijos que viven “entre” la casa de mamá y la de papá. Integración Académica en Psicología, 2(5), 21-28. [ Links ]

Ley N° 20.066 (2005). Ley de violencia Intrafamiliar. Recuperado de: http://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=242648 [ Links ]

Ley N° 20.480 (2010). Ley de Femicidio. Recuperado de: http://www.bcn.cl/de-que-se-habla/promulgacion-femicidio [ Links ]

Ley N° 20.680 (2013). Ministerio de Justicia de Chile. Ley Amor de Papá. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Recuperado de: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1052090&buscar=Ley+20680 [ Links ]

Martínez, R. L. (2003). El conflicto en la vida de la pareja. En O. P. Salud, La familia, su dinámica y tratamiento (pp. 122-124). Washington DC: Instituto Mexicano de Seguridad Social. [ Links ]

Moses, M., & Towsend, B. A. (2011). Parental Alienation in child custody disputes. Tennesee Bar Journal. 47(5), 25-29 [ Links ]

O'Donohue, W., Benuto, L.T. & Bennett, N. (2016). Examining the validity of parental alienation syndrome. Journal of Child Custody, 13 (2-3), 113-125. doi: 10.1080/15379418.2016.1217758 [ Links ]

Pautassi, L. & Royo, L. (2012). Enfoque de derechos en las políticas de infancia: indicadores para su medición. CEPAL, UNICEF. Recuperado de: http://www.derecho.uba.ar/investigacion/investigadores/publicaciones/pautassi-enfoquedederechosenlaspoliticasdeinfancia.pdf [ Links ]

Pepiton, M. B., Alvis, L. J., Allen, K., & Logid, G. (2012). Is parental alienation disorder a valid concept? Not according to scientific evidence: A review of parental alienation, DSM-5 and ICD-11 by William Bernet. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 21(2), 244-253. doi: 10.10 80/10538712.2011.628272 [ Links ]

Pérez, E. & Medrano, L. (2010). Análisis factorial exploratorio: bases conceptuales y metodológicas. Ciencias del Comportamiento, 2(1), 58-66. [ Links ]

Ramírez, D. (2011). Las prácticas de desparentalización que se les imponen a los hombres, tras la separación o el divorcio de su pareja: posibles secuelas psicosociales, para ellos y su prole. Estudio de casos, peritados y dictaminados en el año 2008, para el Juzgado de Familia del Segundo Circuito Judicial. Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Universidad Autónoma de Centro América, San José. [ Links ]

Siracusano, A., Barone, Y., Lisi, G., & Niolu, C. (2015). Parental alienation syndrome or alienating parental relational behaviour disorder: a critical overview. Journal of Psychopathology, 21, 231-238 [ Links ]

Tejedor, M. (2006). El síndrome de alienación parental: una forma de maltrato (2ª ed.). Madrid: EOS. [ Links ]

Zander, J. (2012). Parental Alienation as an Outcome of Paternal Discrimination. New Male Studies: An International Journal, 1(2), 49-62. [ Links ]

Zicavo, N. (2006). ¿Para qué sirve ser Padre? Concepción: Ediciones Universidad del Bio-Bio. [ Links ]

Zicavo, N. (2010). Crianza Compartida. Síndrome de Alienación Parental, Padrectomía, los Derechos de los Hijos ante la Separación de los Padres. México: Trillas. [ Links ]

Zicavo, N. (2016). Parentalidad y Divorcio. (Des)encuentros en la familia Latinoamericana. México, Alfepsi Editorial. [ Links ]

Zicavo, N., Celis, D., González, A., & Mercado, M. (2016). Escala Zicap para la evaluación de la alienación parental: resultados preliminares. Ciencias Psicológicas, 10(2), 177-187. [ Links ]

Zirogiannis, L. (2001). Evidentiary issues with Parental Alienation Syndrome. Family Court Review, 39(3), 334-343. doi: 10.1111/j.174-1617.2001.tb00614.x [ Links ]

How to cite: Zicavo Martínez, N., Rey Clericus, R., y Ponce, L. (2021). ZICAP II Scale: Parental Alienation Assessment in 9 to 15 years-old children of separated parents in Chile. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(1), e-2159. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2159

Authors' participation: a) Concepción y diseño del trabajo; b) Adquisición de datos; c) Análisis e interpretación de datos; d) Redacción del manuscrito; e) revisión crítica del manuscrito. N. Z. M. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; R. R. C. in c, e; L. P. in e.

Received: May 11, 2020; Accepted: December 03, 2020

texto em

texto em