Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.1 Montevideo jun. 2021 Epub 01-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2357

Original articles

Strengths of character: evidence from a scale and prevalence in the Brazilian Northeast

1 Universidade Federal do Piauí, Parnaíba-PI. Brasil

2 Faculdade Regional da Bahia, Parnaíba-PI. Brasil

3Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa-PB. Brasil

This study assesses the prevalence of character strengths among Northeastern Brazilians to, more specifically, gather new psychometric evidence by applying the Character Strengths Scale (CSS) to a sample of 383 people (M age = 27.81; SD = 10.83), mostly single (73.1%) women (65.4%) from Paraíba, Brazil (24.3%), who completed the CSS and answered demographic questions. Exploratory factor analysis indicated the unidimensionality of the scale, with the 24 strengths of character loading on the factor with an eigenvalue of 9.69, explaining 43% of the variance, and with factor loadings ranging from 0.41 (forgiveness) to 0.72 (zest). Cronbach’s alpha (0.94) and McDonald’s omega (0.95) indicated satisfactory scale reliability. Furthermore, descriptive statistics were calculated to identify the most prevalent strengths in the Brazilian Northeast, namely, gratitude, kindness, curiosity, fairness, love of learning and hope, in decreasing order. Evidence is presented for the use of the CSS as well as the influence of culture and region on the prevalence of character strengths.

Keywords: character strengths; virtues; psychological tests; positive psychology; social psychology

Objetiva-se verificar a prevalência das forças de caráter nos nordestinos, especificamente, reunir novas evidências psicométricas da Escala de Forças de Caráter (EFC). Contou-se com uma amostra de 383 pessoas (M idade = 27,81; DP= 10,83) oriunda em sua maioria da Paraíba, Brasil (24,3%), do sexo feminino (65,4%) e solteira (73,1%), que responderam a EFC e questões demográficas. Uma Análise Fatorial Exploratória indicou a unidimensionalidade da escala, as 24 forças saturando no fator com valor próprio igual a 9,69, explicando 43% da variância e cargas fatoriais de 0,41 (perdão) até 0,72 (vitalidade). O alfa de Cronbach (0,94) e ômega de McDonald (0,95) indicaram precisão satisfatória. Ademais, estatísticas descritivas foram realizadas identificando as forças mais prevalentes no Nordeste, respectivamente: gratidão, bondade, curiosidade, imparcialidade, amor ao aprendizado e esperança. Discute-se que a EFC reúne evidências para sua utilização e se discute a influência da cultura e região na prevalência das forças.

Palavras-chave: forças de caráter; virtudes; testes psicológicos; psicologia positiva; psicologia social

Se estudia la prevalencia de las fuerzas de carácter en los nordestinos, específicamente con la intención de reunir evidencias psicométricas de la Escala de Fuerzas de Carácter (EFC). Se contó con una muestra de 383 personas (M edad = 27.81, DE= 10.83) oriunda en su mayoría de Paraíba, Brasil (24.3%), del sexo femenino (65,4%) y soltera (73,1%), que respondieron a EFC y cuestiones demográficas. Un Análisis Factorial Exploratorio indicó la unidimensionalidad de la escala, las 24 fuerzas saturando en el factor con valor propio igual a 9.69, explicando el 43% de la varianza y cargas factoriales de .41 (perdón) hasta .72 (vitalidad). El alfa de Cronbach= .94 y omega de McDonald= .95 indican precisión satisfactoria. Posteriormente, estadísticas descriptivas fueron realizadas identificando como las fuerzas más prevalentes en el Nordeste: gratitud, bondad, curiosidad, imparcialidad, amor al aprendizaje y esperanza. Se plantea que la EFC reúne evidencias psicométricas para su utilización y se discute la influencia de la cultura y región en la prevalencia de las fuerzas.

Palabras-clave: fuerzas de carácter; virtudes; pruebas psicológicas; psicología positiva; psicología social

The good in people has attracted the attention of researchers and professionals in the field of social sciences and health. The study of virtues and character strengths is an example, as this construct has played a key role in the field of Positive Psychology (Noronha & Campos, 2018; Petkari & Ortiz-Tallo, 2016). Virtues concern specific individual capacities related to the thoughts, feelings and actions that compel each person to act in good conscience and that involve specific strengths such as goal achievement (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Conversely, strengths of character are characterized as preexisting and authentic strengths of humans because they enable them to survive in a positive way (Noronha & Zanon, 2018; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

In addition, the use of character strengths is socially valued and positively related to positive personality traits (e.g., kindness and extraversion) (Couto & Fonsêca, 2019; Noronha & Campos, 2018). Character strengths are not only required for enjoying education, controlling excesses, self-regulating emotions and increasing satisfaction with life (Harzer & Ruch, 2013; Noronha & Batista, 2020a) but also essential for pleasant interpersonal and group dynamics, with enhanced perceptions of well-being and mental health (Haridas, Bhullar, & Dunstan, 2017).

In their survey of studies published until 2014, Reppold, Gurgel and Schiavon (2015) found no studies on character strengths in Brazil. Similarly, Pires, Nunes and Nunes (2015) found no instrument based on the model of strengths and virtues published before 2014.

However, some studies on character strengths conducted in Brazil have recently been published (Couto & Fonseca, 2019; Noronha & Batista, 2017; 2020a; 2020b; Noronha & Martins, 2016; Noronha, Silva, & Rueda, 2018; Seibel, DeSousa, & Koller, 2015). In particular, Noronha, Dellazzana-Zanon and Zanon (2015) present excellent psychometric evidence for the Character Strengths Scale (CSS), which was parsimoniously developed for the Brazilian context. Therefore, the study of this construct remains incipient. Nevertheless, this subject is increasingly gaining notoriety thanks to assessment instruments that provide a ranking of the strengths in each region.

Characterized by its authentic nature and potential for presence in all persons, the ranking is dynamic and influenced by the specificities of each region (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seibel et al., 2015). Accordingly, assessing the prevalence of strengths in each country is the foundation for solving everyday social problems (Romero, Guajardo, & Sánchez, 2016) and highlights the framework of Positive Psychology (positive emotions, qualities and institutions) (Noronha & Batista, 2017).

Character strengths can manifest as behaviors, thoughts and/or feelings, are authentic and enable the most ideal functioning possible of a human being (Noronha et al., 2018; Peterson &Seligman, 2004). Hence, as people use strengths of character, they become virtuous (Oliveira, Nunes, Legal, & Noronha, 2018).

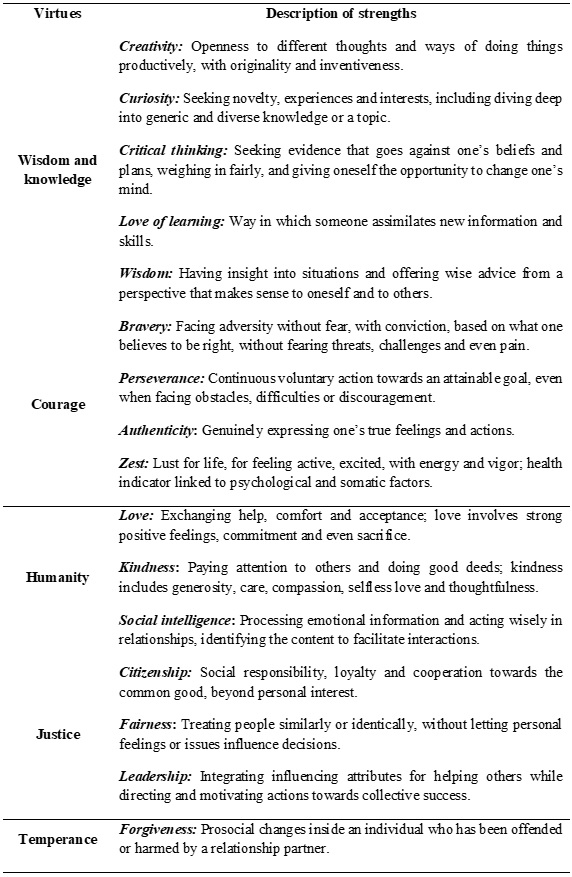

After a literature search, including philosophical and religious traditions, a classification termed Values in Action (VIA) was developed that gathers 24 character strengths theoretically organized into six virtues to describe the potentialities of individuals. For this purpose, the authors defined 10 criteria for a psychological characteristic to be included as strength of character (Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2006; Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). In brief, Freitas, Barbosa and Neufeld (2016) transcribed the criteria gathered by those authors; all, or at least most of them, must be met: (1) is useful and contributes to a good life for oneself and others, (2) beyond producing desirable effects, its use is morally valued, (3) its display by one person does not diminish others, (4) has obvious antonyms that are opposite and negative, (5) its manifestations are stable and able to be measured, (6) distinct from other strengths, (7) embodied in consensual models, (8) present in all age groups, (9) can be selectively and totally absent in some people and (10) is formed in institutions and the target of social practices and rituals that cultivate and sustain the strength.

When using the 24 strengths, an individual may experience feelings such as excitement, eagerness, discovery and invigoration, in addition to becoming a person known for having a good character (Seijts, Crossan, & Carleton, 2017). Therefore, in general, character strengths are likely put into practice socially to foster the six theoretically proposed virtues and therefore to develop good social relationships, increase the capacity for coping with difficult situations and acquire new knowledge and healthy functioning (Noronha & Campos, 2018)

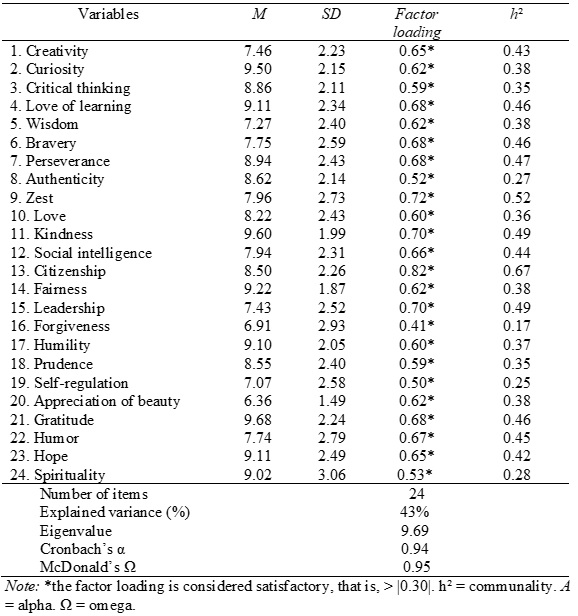

In summary, the model presented in Table 1 was proposed to examine and describe, in detail, the best in human beings and to facilitate the identification, appreciation and daily practice of character strengths, as long as they can be measured. This organization helps readers and researchers, but the classification should be regarded as descriptive, not prescriptive (Niemiec, 2013).

Table 1: Description of character strengths and clustering into virtues, translated into Brazilian Portuguese (adapted

From the proposed theoretical model, the 240-item VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS), with 10 items for each strength, totaling 240 items, was developed as the first step of an empirical study of strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Despite being applied worldwide, this six-factor model, however, has not been found in empirical studies exploring the dimensionality of the construct; in the original study, the structure included five factors (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), similarly to the studies by Azañedo, Fernández-Abascal and Barraca (2014) and by Ruch, Martínez-Martí, Proyer and Harzer (2014). Structures with four (Brdar & Kashdan, 2010) and three (McGrath, 2015) dimensions have also been found.

In Brazil, the VIA-IS was adapted and validated by Seibel et al. (2015), behaving as a single-factor structure. In turn, Noronha et al. (2015) considered the VIA model when designing the CSS, a more parsimonious Brazilian instrument that assesses strengths and has evidence of internal validity (Noronha & Batista, 2020a) and contains external variables such as parenting styles (Noronha & Batista, 2017), personality (Noronha & Campos, 2018) and emotional self-regulation (Noronha & Batista, 2020b). Initially, three items were constructed for each strength, but the appreciation of beauty strength, after analysis by judges, consisted of only two items, totaling 71 items in the CSS. The authors, through robust analyses for item retention (e.g., Hull method, parallel analysis), ultimately identified the unidimensionality of the CSS, thus corroborating the model developed by Seibel et al. (2015) using the VIA-IS.

Although the above findings highlight the variability of the model with culture, strengths of character can be evaluated both specifically (Noronha & Martins, 2016) and globally (Neto, Neto & Furnham, 2014). However, Noronha and Zanon (2018) gathered different psychometric evidence, finding, through exploratory factor analysis, a three-factor structure for the CSS, in a sample of 981 university students from the Brazilian Southeast.

Thus, it is observed that research on strengths and virtues is prominent internationally, but the theoretical six-factor structure originally proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004) has not been replicated empirically. This caveat nevertheless does not prevent advances in the field and the refinement of such scales for assessing the strengths of an individual. More specifically, the CSS had demonstrated satisfactory psychometric evidence, as discussed above, and merits gathering new findings in different regions of Brazil.

However, regardless of the instrument used, character strengths can be studied independently or combined, considering their mutual influence and interrelationship (Noronha & Barbosa, 2016; Seibel et al., 2015). Furthermore, by definition, the 24 strengths are universal, and all individuals have the ability to develop them and to put them into practice to overcome adversities and risk factors, which negatively affect well-being and mental health (Haridas et al., 2017).

Park et al. (2006) and McGrath (2015) conducted studies with samples from different countries, including Brazil, providing further evidence of the universality of the model. However, they noted the inability to make generalizations and the individual nature of character strengths, which are influenced by the specificities of each region and especially by cultural differences, as shown by Hofstede (1991). The latter presented a model of the cultural dimensions that affect the behavior of each individual from each value perspective (power distance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation versus short-term orientation).

More specifically, when applying the model of cultural dimensions developed by Hofstede (1991), Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov (2010) identified that Brazil scores high in power distance, suggesting that individuals accept hierarchies well. Brazil also scores high in collectivist characteristics, defining people as interconnected, and presents characteristics of masculinity, such as competitiveness in pursuit of goals, but quality of life prevails. The high level of uncertainty avoidance also stands out, creating rules and legal systems. Last, the results from the dimension long-term versus short-term orientation showed that Brazilians easily accepts change because they believe that change is part of life (Santana, Mendes, & Mariano, 2014).

In this line, international studies have been conducted to identify the prevalence of character strengths in different countries, such as Spain (Azañedo et al., 2014) and Norway (Boe, Bang, & Nilsen, 2015). In addition, a study conducted in Mexico (Romero et al., 2016) stands out because this country has a Latin American culture similar to the Brazilian culture. Those authors argued that the high prevalence of gratitude and kindness that they found reflects the relationships Mexican people maintain, collectively prioritizing social interactions.

In Brazil, similar studies were conducted by Seibel et al. (2015) and by Noronha et al. (2015) using the VIA-IS and the CSS, respectively, to measure character strengths. However, in the latter, the sample consisted of only university students from São Paulo and Minas Gerais. Thus, different studies should be conducted in other Brazilian regions, with more heterogeneous samples, to help identify the Brazilian profile of character strengths and to provide major indices about the originally proposed model by testing the universality and cultural effects on the ranking.

Based on the above, the present study expands the theoretical and empirical framework of the character strengths of the Brazilian population. Considering the continental characteristics of the country and their effect on the study construct, the following questions arise: What are the psychometric indices of the CSS in the Brazilian Northeast? What is the prevalence of character strengths among residents of the Northeast Region? To answer these questions, this study assesses the prevalence of character strengths among Northeasterners and, more specifically, gathers new psychometric evidence on the CSS. For this purpose, an empirical study was conducted with people from the nine states of the Northeast Region, keeping in mind that the scale already parsimoniously shows acceptable psychometric indices and that the sample is novel. Ultimately, the goal is to gather new evidence of the validity and reliability of this scale, expanding its potential applicability while assessing the strengths of character of Northeastern Brazilians.

Materials and Method

Participants

As inclusion criteria, the participants were at least 18 years old and lived in a city in the Northeast Region of Brazil. Hence, the study sample consisted of 383 respondents with ages ranging from 18 to 72 years (M= 27.81; SD= 10.03); most participants were single (73.1%), childless (74.3%) women (65.4%) with incomplete higher education (46%) from the states of Paraíba (34.3%), Piauí (22.7%) and Pernambuco (13.5%).

Instruments

Character Strengths Scale (CSS): Originally proposed and validated in the context of the Brazilian Southeast (Noronha et al., 2015), the CSS is a 71-item scale (e.g., item 39. I admire the beauty that exists in the world; item 40. I do not give up before reaching my goals) evaluating the 24 character strengths. They are represented by the sum of three specific items for each strength, except appreciation of beauty, which ended up with only two items when developing the scale. The items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 “not at all like me” to 4 “very much like me”, with a higher score suggesting the presence of the evaluated character strength in the daily life of the individual. In the development study, the authors found satisfactory psychometric indices (single-factor structure, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93).

Sociodemographic questionnaire. Set of questions (e.g., age, sex, state of residence, marital status, income, and children) aimed at characterizing the study subjects.

Procedure

The study was conducted after the project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of a public institution in the Northeast Region of Brazil (CAA n. 77974517.8.0000.5188; protocol n. 2.350.522), in accordance with National Health Council resolutions 466/12 and 510/16. For both data collection methods, individuals were invited to voluntarily and anonymously participate in the study, and they were informed about the objectives and characteristics of the study and about the possibility of withdrawing from the study without repercussions. Furthermore, they were also informed about the risks they could face during the administration of the questionnaire, for example, embarrassment when reading some items. Subsequently, after agreeing to participate in the study and signing an informed consent form, the subjects completed the questionnaire, which took, on average, 10 minutes.

Operationally, the booklets containing the questionnaires were administered in person by duly trained collaborators who, at the time, visited randomly selected households in some cities in the Brazilian Northeast. In addition, people present in busy public areas, such as shopping malls and squares, also participated in the study. Data were also collected online by sharing the questionnaires on social media and by e-mail. Both methods of questionnaire administration (face-to-face and online) show similar results in scientific research (Brock, Barry, Lawrence, Dey & Rolffs, 2012).

Data analysis

In AMOS version 23, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using the following indices to assess the model’s goodness-of-fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013): (1) comparative fit index (CFI); (2) Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI); and (3) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval (90% CI). In SPSS version 23, descriptive and dispersion statistics were calculated to characterize the sample and to describe the prevalence of character strengths; Cronbach’s alpha was used to determine the reliability of the CSS. In Factor 10.3 (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2013), the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests were performed to assess the possibility of factoring the data matrix, followed by unweighted least squares (ULS) factor analysis, the Hull method, to identify the factorial structure of the scale in the context of the Northeast Region of Brazil, and McDonald’s omega was calculated to increase the robustness of the reliability.

Results

Initially, the 24 character strengths were computed from item parcels, as suggested in the literature (Noronha & Barbosa, 2016; Noronha & Batista, 2020b). Thus, for each index, the items that represented each strength were added (e.g., the three items that measured kindness were added); accordingly, the six-factor model based on the six theoretically proposed virtues was tested by CFA, which suggested that the structure of the study sample did not show good goodness-of-fit indices (CFI = 0.79, TLI = 0.76, RMSEA = 0.10 (90% CI = 0.09 - 0.12)). To consider the characteristic authenticity and the effect of each region on the organization of strengths, exploratory factor analysis was performed using the 24 character strengths to investigate the factorial model of the CSS in the Brazilian Northeast.

The number of common factors was defined based on the adequacy of the factorial indices of the data matrix (KMO = 0.93; Bartlett’s test (p < 0.05)). ULS factor analysis, using one of the most appropriate and efficient methods for factor retention, the Hull method, in addition to parallel analysis (Damásio, 2012; Lorenzo-Seva, Timmerman, &Kiers, 2011), indicated the unidimensionality of the scale. The psychometric results from the CSS are provided in Table 1, along with the prevalence of the character strengths.

As shown in Table 2, all 24 character strengths satisfactorily loaded on the factor, with an eigenvalue of 9.69, explaining 43% of the total variance, with factor loadings above the recommended threshold (>0.30), ranging from 0.41 (forgiveness) to 0.72 (zest). In addition, other coefficients indicated satisfactory scale reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.94; McDonald’s Ω = 0.95). Furthermore, the most prevalent character strengths in the lives of Northeastern Brazilians in the study sample were gratitude and kindness, followed by curiosity, fairness, love of learning and hope. Moreover, the character strength spirituality had the highest standard deviation, indicating the highest dispersion of and variability in scores.

Discussion

The present study investigated the prevalence of character strengths among Northeastern Brazilians by testing the six-virtue model and by gathering new psychometric evidence for the CSS. The results showed that the objectives of this study were achieved and that the CSS has a single-factor structure, with equally satisfactory model goodness-of-fit indices for research in the context of the Northeast Region of Brazil (Cohen, Swerdlik, & Sturman, 2014; Nunnally, 1978).

The six-factor structure, theoretically designed to organize the character strengths, was not confirmed in the sample of the present study. Thus, the data were explored. The unidimensional structure, found by exploratory analysis, corroborates the structure originally found by the authors (Noronha et al., 2015) and the character strengths model presented by Seibel et al. (2015) in the Brazilian context, similarly to other countries, where alternative models to the original have also been found (Brdar & Kashdan, 2010; McGrath, 2015; Noronha & Zanon, 2018). The differences between models represent the mutable nature of the character strengths of individuals and their affectability by culture. Consequently, organizing character strengths in different models is a theoretical task. The empirical task of evaluating the 24 strengths based on a unidimensional model indicates that they can be analyzed globally and/or specifically, i.e., one by one (Neto et al., 2014; Noronha & Martins, 2016).

Strengths of character are interrelated, and their ranking will likely be specific to the context, even though they can be found universally across cultures and evaluated individually (McGrath, 2015, Noronha et al., 2018). Thus, as one of the objectives of the present study, descriptive statistics were calculated, thereby identifying the most prevalent strengths in the Brazilian Northeast, namely, gratitude, kindness, curiosity, fairness, love of learning and hope, in decreasing order. These results partly match those from the Brazilian Southeast (gratitude, curiosity, hope, kindness and justice) reported by Noronha et al. (2015). Accordingly, the subjects of those studies were grateful for all that life brings and careful and concerned with others and sought new possibilities and ways to cope with situations, in addition to a connection with and exploration of the universe and hopeful thinking, even when facing daily struggles, thus combining strengths of character. Furthermore, the higher standard deviation found in the strength spirituality demonstrated the higher variability in these data, suggesting that some Northeasterners strongly experience spirituality, whereas others still do not use this strength.

The findings of the present study are similar to the results found in Mexico (Romero et al., 2016), clearly representing the Latin American culture as a more collective than individualistic culture (Díaz-Loving, 2005) and highlighting positive characteristics such as treating everyone equally and not focusing on standing out as individuals. The results also showed similarities with the Brazilian profile proposed by Hofstede et al. (2010), which is characterized by concern for the common good above personal well-being. Thus, the most prevalent strengths of character in Brazilian samples are in line with the characteristics presented in a Social Psychology model because, according to Hofstede (1991) and to Hofstede et al. (2010), Brazilians accept hierarchies well and seek competition but prioritize quality of life, in addition to creating rules for uncertainty avoidance and accepting change easily because they believe that change is part of life (Santana et al., 2014).

This topic and the specific discussion of the strengths of character found in the Brazilian Northeast are highly important considering the history of the region, which is marked by people who have overcome geographical adversities and severe droughts, living in places where water is scarce, where basic needs are difficult to meet and where economic investment is low (Gonçalves & Araújo, 2015). These factors may have contributed to the prevalence of the character strengths identified in this study. Overcoming regional obstacles requires teamwork while recognizing and valuing what one has. Above all, due to the specificities of the Brazilian Northeast, the local population will always hope that better days are coming because past experiences of overcoming difficulties suggest a positive outlook. As a result, individuals engage in their daily activities, maintaining their quality of life while making ends meet.

Based on these results, the present study provides further data on the positive profile of Brazilians. These data were more holistically gathered from a more heterogenous sample (different age groups and educational levels) than were data from previous studies conducted in the Brazilian context, which relied on samples of only undergraduate students from the Brazilian Southeast (Noronha & Batista, 2017; 2020a; 2020b; Noronha et al., 2015; Noronha & Zanon, 2018). Thus, the importance of the present study stands out in that cross-cultural studies of Brazil grouped realities by cultural similarities, albeit highlighting the influence and affectability of the characteristics of each region (McGrath, 2015; Park et al., 2006). In this conjecture, the continental dimension and cultural variability of Brazil must be considered.

Accordingly, the limitations of the study sample, which was a nonprobabilistic, convenience sample specific to one of the five regions of Brazil, and the nonexperimental research design preclude extrapolating the results (Breakwell, Hammond, Fife-Chaw, & Smith, 2010). Nevertheless, these caveats do not compromise the results of this study. In turn, the main limitation of the empirical research is the fact of not gathering evidence of the external validity of the CSS, but this gap was bridged by the complementary psychometric evidence for the original scale and for the first models used to analyze the Brazilian Northeast.

Future studies and advances in this field should include other scales with similar data collections to assess the external validity of the measure and identify relationships and effects of social, individual (e.g., human values, personality) and demographic (e.g., sex, age) variables on the prevalence of strengths of character. In addition, collecting data more probabilistically on a more diversified sample from different regions of Brazil would help detect changes in the character strengths profile of Brazilians. Data could also be collected using other instruments, in addition to psychometric scales, such as interviews, focus groups and observations specifically assessing the use of character strengths in daily life.

Thus, following the strategies described above would enable us to gain a robust overview of the positive qualities of people and to collect complete data on the benefits experienced by those who use their character strengths on a daily basis (e.g., excitement, discovery, and invigoration) and are therefore socially recognized as people with a good character, that is, who gather and externalize positive and unifying traits at both the individual and social levels (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seijts et al., 2017). In addition, those approaches would also enable us to plan interventions to analyze the effectiveness of character strengths in overcoming difficult situations (Proyer, Gander, Wellenzohn, & Ruch, 2015; Renshaw & Steeves, 2016) while furthering studies on positive constructs (Pires et al., 2015; Reppold et al., 2015).

Conclusion

The present study confirmed the psychometric qualities of the CSS, providing a parsimonious alternative for researchers interested in using this scale in the context of the Northeast Region of Brazil. Furthermore, this study discusses the mapping of character strengths based on their prevalence, corroborating the field-specific literature when identifying the effect of culture and region on the ranking of the 24 strengths. In summary, our study consolidated the theoretical framework of this subject and analyzed the importance of using individual character strengths for increasing quality of life and experiencing healthy functioning in all areas of life.

REFERENCES

Azañedo, C. M., Fernández-Abascal, E. G., & Barraca, J. (2014). Character strengths in Spain: Validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) in a Spanish sample. Clínica y Salud, 25(2014), 123-130. doi: 10.1016/j.clysa.2014.06.002 [ Links ]

Boe, O., Bang, H., & Nilsen, F. A. (2015). Experienced military officer’s perception of important character strengths. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 190(2015), 339-345. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.008 [ Links ]

Brdar, I., & Kashdan, T. B. (2010). Character strengths and wellbeing in Croatia: An empirical investigation of structure and correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 151-154. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.12.001 [ Links ]

Breakwell, G. M., Hammond, S., Fife-Schaw, C., & Smith, J. A. (Orgs.). (2010). Métodos de pesquisa em psicologia (3ª ed). Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed. [ Links ]

Brock, R. L., Barry, R. A., Lawrence, E., Dey, J., & Rolffs, J. (2012). Internet administration of paper-and-pencil questionnaires used in couple research: Assessing psychometric equivalence. Assessment, 19(2), 226-242. doi: 10.1177/1073191110382850 [ Links ]

Cohen, R. J., Swerdlik, M. E., & Sturman, E. D. (2014). Testagem e Avaliação Psicológica: Introdução a Testes e Medidas. (8º ed) São Paulo: AMGH. [ Links ]

Couto R. N., &. Fonsêca P. N. (2019). Character strengths in the Brazilian northeast region: contributions of personality beyond age and sex. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 36, e18137. doi: 10.1590/1982-0275201936e180137 [ Links ]

Damásio, B. F. (2012). Uso da análise fatorial exploratória em psicologia. Avaliação Psicológica, 11(2), 213-228. [ Links ]

Díaz-Loving, R. (2005). Emergence and contributions of a Latin American indigenous social psychology. International Journal of Psychology, 40(4), 213-227. doi: 10.1080/00207590444000168 [ Links ]

Freitas, E. R., Barbosa, A. J. G., & Neufeld, C. B. (2016). Forças do caráter de idosos: Uma revisão sistemática de pesquisas empíricas. Psicologia em pesquisa, 10(2), 85-93. doi: 10.24879/201600100020054 [ Links ]

Gonçalves, H. F., & Araújo, J. B. (2015). Evolução histórica e o quadro socioeconômico do Nordeste brasileiro nos anos 2000. Revista do Desenvolvimento Regional - Faccat - Taquara/RS, 12(1). 193-204. [ Links ]

Haridas, S., Bhullar, N., & Dunstan, D. A. (2017). What's in character strengths? Profiling strengths of the heart and mind in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 113(2017), 32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.006 [ Links ]

Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2013). The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 965-983. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9364-0 [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M., (2010). Cultures and organizacións: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw Hill [ Links ]

Lorenzo-Seva, U., Timmerman, M. E., & Kiers, H. A. L. (2011). The Hull Method for Selecting the Number of Common Factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(2), 340-364. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.564527 [ Links ]

Lorenzo-Seva, U. & Ferrando, P. J. (2013). FACTOR 9.2: A Comprehensive Program for Fitting Exploratory and Semiconfirmatory Factor Analysis and IRT Models. Applied Psychological Measurement, 37(6), 497-498. doi: 10.1177/0146621613487794 [ Links ]

McGrath, R. E. (2015): Character strengths in 75 nations: An update. The Journal of Positive Psychology: Dedicated to furthering research and promoting good practice, 10(1), 41-52. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.888580 [ Links ]

Neto, J., Neto, F., & Furnham, A. (2014). Gender and Psychological Correlates of Self-rated Strengths Among Youth. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 315-327. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0417-5 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Barbosa, A. J. G. (2016). Forças e virtudes: escala de Forças de Caráter. In C. S. Hutz (Org.), Avaliação em psicologia positiva: técnicas e medidas (pp. 21-43). São Paulo: Hogrefre. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2017). Escala de forças e estilos parentais: estudo correlacional. Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia, Londrina, 8(2)02-19. doi:10.5433/2236-6407.2016v8n2p02 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P. & Batista, H. H. V. (2020a). Relações entre forças de caráter e autorregulação emocional em universitários brasileiros. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 29(1), 73-86. doi: 10.15446/.v29n1.72960 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P. & Batista, H. H. V. (2020b). Análise da estrutura interna da Escala de Forças de Caráter. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(1), 1-12. doi: 0.22235/cp.v14i1.2150 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Campos, R. R. F. (2018). Relationship between character strengths and personality traits. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 35(1), 29-37. doi: 10.1590/1982-02752018000100004 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L., & Zanon, C. (2015). Internal structure of the Strengths and Virtues Scale in Brazil. Psico USF, 20(2), 229-235. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200204 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P. & Martins, D. F. (2016). Associações entre Forças de Caráter e Satisfação com a Vida: Estudo com Universitários. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 19(2), 97-103. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2016.19.2.5 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., Silva, E. N., & Rueda, F. J. M. (2018). Relaciones entre fortalezas del carácter y percepción de apoyo social. Ciencias Psicológicas ,12(2), 187-193. doi: 10.22235/cp.v12i2.1681 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P. & Zanon, C. (2018). Strenghts of Character of Personal Growth: Structure and Relations with the Big Five in the Brazilian Context. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 28(e2822). doi: 10.1590/1982-4327e2822 [ Links ]

Oliveira, C., Nunes, M. F. O., Legal, E. J., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2016) Bem-Estar Subjetivo: estudo de correlação com as Forças de Caráter. Avaliação Psicológica ,15(2), 177-185. doi: 0.15689/ap.2016.1502.06 [ Links ]

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Character strengths in fifty-four nations and the fifty US states. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(3), 118-129. doi: 10.1080/17439760600619567 [ Links ]

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and Classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Petkari, E., & Ortiz-Tallo, M. (2016). Towards Youth Happiness and Mental Health in the United Arab Emirates: The Path of Character Strengths in a Multicultural Population. Journal of Happiness Studies , 19, 333-350. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9820-3 [ Links ]

Pires, J. G., Nunes, M. F. O., & Nunes, C. H. S. (2015). Instrumentos Baseados em Psicologia Positiva no Brasil: uma Revisão Sistemática. Psico-USF, Bragança Paulista, 20(2), 287-295. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200209 [ Links ]

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2015). Strengths-based positive psychology interventions: A randomized placebo-controlled online trial on long-term eff ects for a signature strengths- vs. a lesser strengthsintervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(456), 1-14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00456. [ Links ]

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA Character Strengths: Research and Practice (The First 10 Years). Em H. H. Knoop & A. Delle-Fave (Eds.), Well-Being and Cultures (pp. 11-29). New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc. [ Links ]

Renshaw, T., & Steeves, R. M. O. (2016). What good is gratitude in youth and schools? A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates and intervention outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 286-305. doi: 10.1002/pits.21903. [ Links ]

Reppold, C. T., Gurgel, L. G., & Schiavon, C. C. (2015). Research in Positive Psychology: a Systematic Literature Review. Psico-USF, Bragança Paulista , 20(2), 275-285. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200208 [ Links ]

Romero, N. A. R. C., Guajardo, J. G., & Sanchez, A. M. (2016). Las fortalezas de los mexicanos, un análisis desde la autopercepción. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología: ciencia y tecnología, 9(1), 73-84. [ Links ]

Ruch, W., Martínez-Martí, M. L., Proyer, R. T., & Harzer, C. (2014). The character strengths rating form (CSRF): development and initial assessment of a 24-Item rating scale to assess character strengths. Personality and Individual Differences , 68, 53-58. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.042 [ Links ]

Santana, D. L. de; Mendes, G. A.; Mariano, A. M. (2014). Estudo das dimensões culturais de Hofstede: análise comparativa entre Brasil, Estados Unidos e México. C@LEA - Revista Cadernos de Aulas do LEA, Ilhéus, 3, 1-13. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist , 60, 410-421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410 [ Links ]

Seibel, B. L., DeSousa, D., & Koller, S. H. (2015). Adaptação brasileira e estrutura fatorial da escala 240-item VIA Inventory of Strengths, Psico-USF, 20(3), 371-383. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200301 [ Links ]

Seijts, G., Crossan, M., & Carleton, E. (2017). Embedding leader character into HR practices to achieve sustained excellence. Organizational Dynamics, 46 (2017), 30-39. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.02.001 [ Links ]

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6ª ed.). Nova Iorque: Allyn & Bacon [ Links ]

Note: This study is derived from the doctoral dissertation of the first author, who was supervised by the second author

Funding: Financial support provided by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES), which awarded doctoral scholarships to the first and third authors, and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq), which awarded a research productivity grant to the second author. We take this opportunity to show our gratitude to these institutions

How to cite: Couto, R.N., Fonseca, P.N., Silva, P.G.N., & Medeiros, P.C.B. (2021). Strengths of character: evidence from a scale and prevalence in the Brazilian Northeast. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(1), e-2357. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2357

Correspondence: Ricardo Neves Couto, e-mail: r.nevescouto@gmail.com; Patrícia Nunes da Fonsêca, e-mail: pnfonseca.ufpb@gmail.com, Paulo Gregório Nascimento da Silva, e-mail: silvapgn@gmail.com; Paloma Cavalcante Bezerra de Medeiros, e-mail: palomacbmedeiros@gmail.com

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. R.N.C. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; P.N.F. in a,b,c,d,e; P.G.N.S. in c,d,e; P.C.B.M in c,d,e.

Received: March 30, 2020; Accepted: October 27, 2020

texto em

texto em