Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.15 no.1 Montevideo jun. 2021 Epub 01-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2355

Original articles

The marital relationship from the perspective of couples

1 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Brasil

Marital relationships have been widely investigated. However, there is little clarity about the definition, theoretical contextualization, and the comprehensiveness of the concept of marital quality. Thus, this study aimed to clarify the marital quality construct by proposing dimensions that elucidate an intersection of themes related to the individual, the context, and the adaptive processes, from the perspective of couples. Eight couples answered a semi-structured interview on their marital relationship, which was examined through a thematic analysis. Twenty-one themes were identified, divided into four thematic axes based on the model: individual, context, adaptive processes, and marital quality. Adaptive processes played a central role, as the relationships between the individual and the context axes with the marital quality axis permeate these processes. The importance of adaptive processes in couple interventions is emphasized and further investigation of the adopted model in Brazil is recommended.

Key Words: marital relations; marriage; marital quality; individuality; context

As relações conjugais têm sido amplamente estudadas, porém, há pouca clareza sobre a abrangência, a definição e a contextualização teórica do conceito de qualidade conjugal. Assim, este estudo buscou aclarar o construto de qualidade conjugal propondo dimensões que elucidem a intersecção de a temas relativos ao indivíduo, ao contexto e os processos adaptativos, na perspectiva de casais. Oito casais responderam a uma entrevista semiestruturada sobre o relacionamento conjugal que foi submetida a uma análise temática. Foram identificados 21 temas, divididos em 4 eixos constitutivos do modelo: indivíduo, contexto, processos adaptativos e qualidade conjugal. Os processos adaptativos tiveram papel central, sendo que as relações entre os eixos indivíduo e contexto e o eixo qualidade conjugal perpassam esses processos. Ressalta-se a importância dos processos adaptativos nas intervenções com casais e recomenda-se que a pertinência do modelo adotado continue sendo investigada no Brasil.

Palavras-chave: relações conjugais; casamento; qualidade conjugal; indivíduo; contexto

Las relaciones conyugales han sido ampliamente investigadas, sin embargo, hay poca claridad sobre el alcance, definición y contextualización teórica del concepto de calidad conyugal. Así, este estudio buscó aclarar el constructo calidad conyugal proponiendo dimensiones que elucidan la intersección de temas relacionados con el individuo, el contexto y los procesos adaptativos, desde la perspectiva de las parejas. Ocho parejas respondieron a una entrevista semiestructurada sobre la relación matrimonial, la cual se sometió a un análisis temático. Se identificaron veintiún temas, divididos en cuatro ejes basados en el modelo: individuo, contexto, procesos de adaptación y calidad conyugal. Los procesos de adaptación jugaron un rol central, y las relaciones entre los ejes individuo y contexto y los ejes de calidad conyugal permean estos procesos. Se enfatiza la importancia de los procesos de adaptación en las intervenciones con parejas y se recomienda seguir investigando en Brasil el modelo adoptado debido a su relevancia.

Palabras Clave: relaciones conyugales; matrimonio; calidad conyugal; individuo; contexto

Intimate and loving relationships are considered an important aspect of adult life (Rosado & Wagner, 2015), and the quality of these relationships has impacts on the individual and the family health (Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2014; Stroud, Meyers, Wilson, & Durbin, 2015) of the spouses. Currently, the way love relationships are experienced has undergone transformations, motivating researchers to investigate new marital arrangements, such as couples without children by choice (Silva & Frizzo, 2014), homosexual couples (Lomando, Wagner, & Gonçalves, 2011; Meletti & Scorsolini-Comin, 2015), and dual career couples (Heckler & Mosmann, 2016). In addition to new arrangements and configurations, the way of understanding and experiencing relationships has also been changing. There is greater appreciation of individual freedom and satisfaction (Borges, Magalhães, & Féres-Carneiro, 2014), so that the marital bond fosters the personal growth of each member of the couple. These new arrangements, however, still coexist with more traditional relationship models and values (Costa & Mosmann, 2015).

In addition to the challenges brought about by these changes and the coexistence of different models, there is a difficulty that has extended for decades in the literature to define what a quality marital relationship is (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987; Heyman, Sayers, & Bellack, 1994; Mosmann, Wagner, & Féres-Carneiro, 2006). The fact that different terms, such as quality, satisfaction, adjustment, and happiness are used interchangeably as synonyms or different concepts, demonstrates the difficulty of researchers in reaching a consensus on the topic (Delatorre & Wagner, 2020; Rosado & Wagner, 2015; Scorsolini-Comin & Santos, 2010). This difficulty extends beyond the choice of terms used to the definition of the very nature of the construct. For some authors, quality and marital satisfaction are synonymous, representing a one-dimensional construct determined by the global assessment that spouses make of the relationship (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987; Norton, 1983). For others, it is a complex construct that involves different dimensions of the relationship, in addition to marital satisfaction (Fletcher, Simpson, & Thomas, 2000; Mosmann et al., 2006, Spanier & Cole, 1976).

In view of this scenario, some authors have mapped concepts and theories that explain the marital quality construct and marital relations as a whole, aiming at identifying their contributions to the understanding of the construct (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Mosmann et al., 2006). These studies reveal the complexity involved in studying the theme and point to the need for integrative models, which consider the couple’s relationship from different perspectives (Mosmann et al., 2006). In this sense, Karney and Bradbury (1995) developed the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model, combining the most important contributions of each of the reviewed theories.

The model not only aims at explaining marital quality, but also stability and changes in the relationship over time, highlighting three groups of variables: stressful events, individual vulnerabilities, and adaptive processes. According to the model, the stressful events that are part of the couple’s context and the individual vulnerabilities of the spouses influence the adaptive processes of the couple. These processes represent how the couple interacts and responds to each other and to factors external to the relationship. Adaptive processes, in their turn, establish a reciprocal association with marital quality. This definition is useful to demarcate the differences between the components of marital quality and adaptive processes, avoiding the overlap of constructs that tend to skew studies investigating marital quality (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987). However, one of the limitations of the model is to consider quality and marital satisfaction as synonyms, reducing the quality of the relationship to a subjective assessment of the spouses. Despite avoiding conceptual overlap, this type of definition makes it difficult to determine what constitutes marital quality and what is the theoretical construction of the construct (Knapp & Lott, 2010).

In this sense, the Triangular Theory of Love (Sternberg, 1986) also proposes an integrative view of relationships although the focus is on love and not on the relationships themselves. According to Sternberg, love is made up of three components: intimacy, passion, and decision/commitment. These components are derived from emotional investment, motivational involvement, and cognitive decision, respectively. Each component has a specific role, from falling in love and forming the couple, through the development of the marital bond, to maintaining the stability of the relationship. Thus, in the same way that the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model makes it possible to discriminate adaptive processes and marital quality, the Triangular Theory of Love offers a framework for understanding the components of the construct.

In Brazil, some studies have already been carried out based on Sternberg’s theory. Mônego and Teodoro (2011), for example, found significant correlations between the three components of love and marital satisfaction. The authors also investigated the components of love, the traits of the five major personality factors, and the type of relationship as predictors of marital satisfaction. Higher levels of intimacy, passion, and the trait of conscientiousness, as well as less neuroticism, were predictors of satisfaction with the relationship. In the same direction, the findings by Rizzon, Mosmann and Wagner (2013) revealed significant correlations between the three components of love and marital satisfaction in people who had been in a relationship for more than 10 years. In the study conducted by Rizzon et al. (2013), however, the commitment component was predominant in relation to the others, which can be explained by the search for financial stability and security in the phase of the life cycle in which the couples were.

In addition to these theories proposed between the 70s and 90s, there are more recent initiatives in the field of conjugality presenting theoretical and methodological refinement. Fowers and Owens (2010), for example, propose an eudaimonic approach, in which marital satisfaction emerges from the degree of correspondence between the relationship and the goals set for the relationship. These goals are classified into two dimensions: agency and communion. Agency is concerned with the relationship between the ends and the means of the goals, which can be instrumental, in which a means is used to achieve a certain end, or constitutive, in which means and ends are inseparable, since the means of achieving a certain goal is an end in itself. Communion differentiates individual goals from those shared between the couple. In this perspective, having a good job and family economic planning are individual and shared goals, respectively, and are also both instrumental goals. Examples of constitutive goals are to assume responsibilities, an individual goal, and to build a harmonious relationship, a shared goal. According to this perspective, higher quality relationships would have high levels of goals that are shared and constitutive.

Analyzing these theories, it is noted that, although they shed light on the variables that influence the quality of the relationship, it is not clear what each of them considers as marital quality itself. It is possible to notice, however, that some theories focus on the perception and evaluation of the spouses, while others emphasize behaviors, or combine both aspects. Among the latter, integrative theories, such as the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model, tend to better encompass the complexity of marital relationships (Mosmann et al., 2006). However, the application of complex and integrative models often results in a tangle of concepts that are difficult to distinguish from each other. In this sense, it is important that the constructs that compose the model be clear, well-defined, and operationalizable.

In addition to the difficulty in defining what marital quality is, few studies have investigated the peculiarities of the perception of romantic relationships in the Brazilian context. Although some studies have investigated the experience of specific groups, such as dual career couples (Heckler & Mosmann, 2016), remarried couples (Silva, Trindade, & Silva Junior, 2012) and differences between marital relations in two generations (Coutinho & Menandro, 2010), no studies that investigated the dimensions of the quality of the marital relationship and which aspects are related to this quality in the Brazilian context were found. Knowing the couples’ experience and their perspective on what a quality relationship is can contribute to the theoretical development of the field in a manner consistent with the local context, in addition to providing tools for working with couples. Thus, the aim of this study was to propose relevant dimensions to the marital quality construct, from the perspective of the interviewed couples, which was understood based on the Triangular Theory of Love (Sternberg, 1986). Furthermore, how these dimensions connect to themes related to the individual, the context and the adaptive processes experienced by couples were also investigated, based on the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995).

Method

Participants

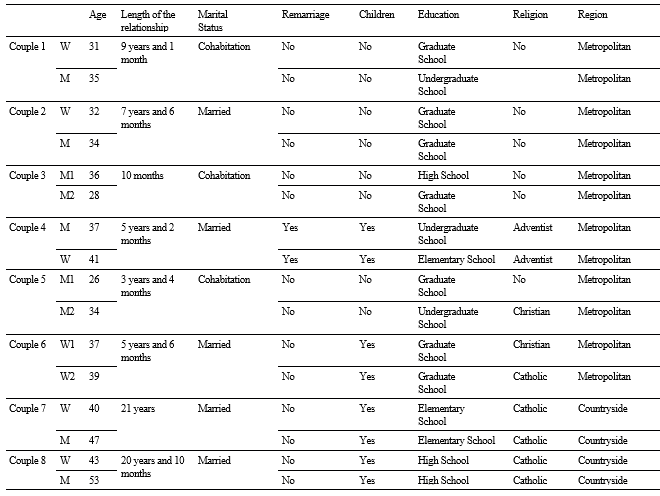

Eight couples, five heterosexual and three homosexuals, participated in the study. As for the marital status, five couples were officially married and three lived together. The length of the relationships ranged from 10 months to 21 years. All couples lived in the Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil, six in the metropolitan region and two in the countryside. Table 1 details the profile of the couples interviewed.

Instruments and data collection procedures

The participants answered a sociodemographic data sheet and a semi-structured interview, which was conducted in the presence of both members of the couple. The interview investigated several aspects of the relationship, such as the couple’s history, the characteristics of the spouse that they would like to highlight, decision making, communication, showing affection, handling conflicts, and the aspects considered necessary for a quality relationship. Questions related to decision-making, communication, displays of affection and conflict management were asked from two perspectives. First, the couple was asked to identify, by mutual agreement, happy moments in the relationship, and then, questions related to this period were asked. The same procedure was then followed considering the difficult moments of the relationship. The questions were answered by both members of the couple, and when only one spouse provided an answer, it was verified whether it corresponded to the perception of both. Two pilot interviews were carried out in order to verify if the elaborated script would be understood by the couples and if it would meet the research objectives. In addition to answering the interview, the couples who participated in this stage were asked to give their opinion on the understanding of the questions and the scope of the interview. There were no changes in the interview after this procedure.

As for the participants, they were selected from the researchers’ network. The convenience criterion was adopted in order to cover the different configurations and phases of the marital/family life cycle as much as possible for the composition of the sample. The interviews were carried out in a previously scheduled meeting, after signing the Free and Informed Consent Form, and lasted about one hour. They were recorded in audio and transcribed in full for analysis. Participants were informed that there were no risks foreseen in participating in the study, but that, if they were uncomfortable with any question, they could choose not to answer or stop participating in the research. In addition, it was ensured that they would be referred to a free psychological care service if necessary. This study was carried out in accordance with the rules provided for in Resolution 466/12 (Conselho Nacional de Saúde, 2012), which provides for the conduct of research involving human beings in Brazil, and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul.

Data Analysis

The content obtained from the interviews was submitted to thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The identification of the thematic axes was carried out based on the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model, previously described. Thus, the thematic axes were defined a priori, whereas the themes were determined based on the content of the interviews. This model has the advantage of allowing the exploration of several variables, grouping stressful events, individual vulnerabilities, and adaptive processes. The authors compared this approach to the inclusion of items in a questionnaire as the relationships between these groupings of variables that form the theoretical construct are more important than the intercorrelations between the variables that compose the model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). In this study, marital quality was considered from a similar perspective, in order to identify the themes that compose the construct, in contrast to the approach adopted by the authors of the model, who consider marital quality as synonymous with relationship satisfaction. For this reason, the Triangular Theory of Love (Sternberg, 1986) was used as a reference to understand the themes that compose marital quality.

Thematic analysis was carried out using the NVivo 11 software. The identified themes were analyzed for agreement by four judges, maintaining those with a Kappa index of concordance equal to or greater than 75%. The Kappa index was calculated from the sum of answers on the same topic divided by the number of judges and multiplied by 100. The answers that obtained 50% of concordance were evaluated by a Professor with expertise in the area and the others were disregarded in the analysis.

Results

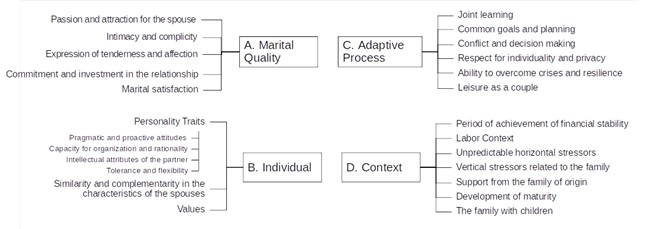

Data analysis identified five themes that make up the quality axis of the marital relationship. Other 16 themes associated with marital quality were identified and organized into three thematic axes: individual, context, and adaptive processes, established from the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). A graphical representation of the thematic axes and themes is presented in Figure 1.

A. Marital Quality Axis

The marital quality axis concerns the assessment of the spouses about their relationship, which involves affection, intimacy, commitment, and sexuality. The contents included in this axis were obtained mainly from the description of happy moments in the relationship, in which the participants addressed the history of the relationship, the characteristics they would highlight in the spouse, the demonstration of affection and the aspects considered important for a good quality relationship. These aspects relate to each other to the extent that attraction and sexuality are important elements at the beginning of the relationship, subsequently giving space to the development of affection and intimacy, which impel partners to commit and invest in the relationship. They are expressed in the following themes:

A.1. Passion and attraction for the spouse. The reports about the relationship included references to the physical and aesthetic aspects of the spouse, in addition to the passion, sexual attraction, and experience of sexuality by the couple: “I… am still in love with her, you know” (Man, Couple 1); “You have to be horny (...) the skin thing has got to work” (Woman 1, Couple 6); “Beautiful (…) she is still beautiful” (Man, Couple 8). Although they were mentioned as important at the present time, these aspects were identified as more relevant at the beginning of the relationship.

A.2. Intimacy and complicity. Intimacy appeared as the spouses’ experience of getting to know each other deeply, demystifying idealized aspects about the partner and favoring non-verbal communication, based on the familiarity with the other’s forms of expression in different situations: “because we’ve been together for quite a long time, right?... We already know, we know... if the other person needs this or that, if they want something.” (Man, Couple 8). From intimacy, it is possible to share experiences and feelings with the spouse, provided by openness to the partner, in addition to experiencing feelings of closeness, complicity, and belonging to the relationship: “Complicity... of knowing that you can share not only the good things with the person, but also the bad ones.” (Woman, Couple 2); “The feeling of belonging to someone, of making sense to someone” (Woman, Couple 4).

A.3. Expression of tenderness and affection. The importance of showing love, tenderness, and affection for the partner was also highlighted in the couples’ reports, covering behaviors such as performing activities together, talking and expressing affection in a physical way, exchanging hugs, kisses, and caresses: “when we are together, we sit down, have a drink, we get close and talk, hug, kiss” (Man 2, Couple 5). The expression of affection also included showing care and concern for the other and making small favors for the spouse: “I think we have a lot of that, these little niceties, like this (…) cooking what the other likes, buying what the other likes eating, likes making ”(Woman 1, Couple 6).

A.4. Commitment and investment in the relationship. Investment in the couple’s daily life appears with the role of maintaining the relationship. This investment requires commitment to the relationship, involving mutual support, companionship, effort, dedication and interest on the part of both spouses: “the couple has to be committed to work out” (Man, Couple 4); “It was very important for our relationship, thus, to walk together and try to support each other at times like these” (Woman, Couple 2); “This good coexistence, this family environment, and one compensates the other, companionship, partnership, the need for the help that you need” (Woman, Couple 8). Some reports also indicate the importance of clarity about expectations in relation to the relationship: “I am clear about what I want, she is clear about what she wants. (...) We know, from the beginning we knew that we wanted someone to be together, to have a child, to have a family, to... go camping on vacation, you know”(Woman 1, Couple 6).

A.5. Marital satisfaction. This theme comprises the contents related to the assessment that the participants make of the relationship. These assessments cover both current and past moments of the couple, analyzing the relationship as a whole and the impact of the relationship on their own life: “We are at the best time of all that we have ever lived” (Woman, Couple 1); “I say that I wouldn’t be the person I am, not without her, no way” (Man, Couple 8).

The marital quality axis demonstrates how the themes that compose the relationship assessment are articulated to integrate the couple’s perception of their conjugality. It can be assumed that the role and importance of the elements of marital quality vary over time although all of them are always present in the relationship to some extent. Passion, for example, tends to be important as a motivating element at the beginning of the relationship. Even losing space as intimacy is constructed, which will provide cohesion in the relationship, passion is still present through the couple’s sexuality. Similarly, commitment and investment assume greater importance when a relational base is already built. The development of the relationship based on attraction and passion, however, would not be possible in the absence of some level of investment and willingness on the part of the members of the couple. Thus, a multidimensional view of marital quality considers all of its elements in a contextualized way at the couple’s current moment.

B. Individual Axis

The individual axis deals with the personal characteristics, values, and particularities brought to the relationship by the members of the couple individually. The contents presented in this axis come mainly from reports on the couple’s history and on the characteristics that each participant highlighted in the partner. Personal characteristics are pointed out as an important aspect, both those of the spouse’s personality and values that are admired by the interviewees as well as important personal attributes for marital relationships in general. Couples recognize that both the similarity and the complementarity of characteristics are important for the good development of the relationship.

B.1. Personality Traits. This theme portrays specific characteristics that call the attention of the partner, such as pragmatism, rationality, and intellectual aspects. Personal characteristics that participants consider for relationships in general are also included. These characteristics are organized in the four sub-themes described below:

B.1.1 Pragmatic and proactive attitudes. With regard to proactivity and pragmatism, the role of taking the initiative, struggling, and being pragmatic for the couple to work out well is highlighted: “this will, this... restlessness to seek, to be always wanting new things. Whether or not he is doing one thing, he already wants two and, going forward, he is always going forward.” (Male 2, Couple 5); “Committed, hard-working” (Man, Couple 8).

B.1.2 Capacity for organization and rationality. Characteristics such as calmness, rationality, balance, management and organization skills were also highlighted by the participants: “it is the capacity for management, organization (…) I look at him and see him as someone important, as someone reliable” (Man 1, Couple 5).

B.1.3 Intellectual attributes of the partner. The intellectual aspects of the spouse, such as intelligence and articulation, were classified by the participants as attractive and important characteristics in the beginning and/or in maintaining interest in the partner: “it is a partnership that challenged me intellectually, so to say. I think this is cool, it still is like this, today” (Man, Couple 2).

B.1.4. Tolerance and flexibility. In this sub-theme, the participants emphasize the importance of tolerance, patience, the ability to act empathetically and reveal spouse characteristics or everyday attitudes and situations, acting in a thoughtful and flexible way: “The ability to overlook things that are, that are not important, you know, that’s are not worth it”(Woman 2, Couple 6); “The biggest challenge in the relationship is tolerance, patience. Without tolerance and patience, there is no marriage” (Woman, Couple 8).

B.2. Similarity and complementarity in the characteristics of the spouses. Participants refer to the importance of both similarity and characteristics in common between the couple and the existence of complementary aspects between spouses. The similarity refers to similarities in thinking and sense of humor, affinity, harmony and the existence of characteristics in common: “Yes. We liked the same things, we liked to go out…” (Woman, Couple 7). Despite the importance of affinity, the existence of antagonistic and complementary aspects in each spouse was also pointed out as favoring the relationship: “there are really antagonistic things that complement each other, I think we help each other in that sense” (Male 1, Couple 3). Rationality, for example, appears as a complement to proactivity, so that one spouse plays a considered role while the other takes the lead in the actions: “I am the one who says ‘no, calm down...’, ‘wait a minute...’ And then she says ‘no, no wait a minute, let’s do things’” (Man, Couple 2).

B.3. Values. Values, including individual, family, and cultural values, faith, and the way in which each spouse was raised were also considered important. Participants point out the role of similarity or difference in values, cultural traits, and ways of creating each one of them in the relationship: “if the values are in agreement, I think the rest... works” (Male 1, Couple 3 ). Faith and religion were identified as having an important role in the relationship by some couples. The reports express the strength and trust obtained through faith, the participation of the couple and/or the family in religious rituals and the importance of values linked to religion for the couple: “And something else is God, right, we have to, we try to follow a religion, right, the Catholic religion. We try to pass this on to the kids, we try to pray together as a family” (Man, Couple 8).

The individual axis portrays how the specific characteristics brought to the relationship by the spouses and the perception that each has of the other’s characteristics set the tone for the processes that occur between the couple. In this sense, both the personal values and the personality traits of each spouse are important. The traits identified, considering the five major personality factors, were: conscientiousness (management and organization skills), openness to experience (seeking new things) and agreeableness (empathy), but not extraversion and neuroticism. These characteristics play a role since the beginning of the relationship, once they are taken into account in the marital choice. In addition, the characteristics themselves as the way they combine between the couple form the basis of the adaptive processes, which will be discussed below.

C. Adaptive Process Axis

The adaptive processes axis includes the processes of interaction, decision making, and relationship building, including the establishment of common goals and the definition of how the couple enjoys the time they spend together, which enables growth and the establishment of a marital identity. Couples point out the importance of trust and respect between spouses in the development of these processes. In addition, this axis includes the perception of security about maintaining the relationship, which comes from the decision to continue the marriage even when there are doubts and difficulties. Most of the content in this axis was obtained from questions about decision making, communication and conflict management both at happy and at difficult moments of the relationship.

C.1. Joint learning. The participants made several references to the maturation of the relationship, to the learning obtained in the face of crisis situations by the couple and the adaptation to life as a couple that occurs as a result of living together and becoming familiar with each other: “because we got to know each other better, we discovered some qualities and other flaws of each other, and we also always aim to grow together”(Male 2, Couple 5). This theme also expresses the participants’ understanding that the marital relationship is a constant construction, which occurs from the couple’s daily life: “this battle that you live there, day by day, also ends up strengthening the relationship, right?”(Man, Couple 8).

C.2. Common goals and planning. The importance of having common plans and goals was also highlighted by the spouses. The existence of joint projects and the search for the growth of both help to unite the couple: “Focus... the same goal, the same target... you have to want the same thing. I want to get there...’, ‘ah, me too’, ‘so let’s do it together’.” (Woman, Couple 4). Although most of the interviewed couples pointed out the importance of long-term planning, some participants also warned of the importance of living in the present and focusing on short-term planning: “this thing of thinking too much about the future, planning things, ‘ah, when that happens’, I think it is harmful (...) it ends up... taking you away from the present, putting you ahead” (Man 1, Couple 3).

C.3. Conflict and decision making. The way in which spouses interact at times of conflict and decision making permeated all interviews. Generally speaking, spouses are divided between those who most often ignore the subject of conflict or keep it to themselves, trying“not to pay attention” and “keep quiet”, and those who tend to act more reactively, saying what they feel and, sometimes, “bursting out”: “I am much calmer, much more quiet (…) So... when he comes and speaks, he explodes like this, normally, I try ‘calm down, calm down”, but there are moments when we get out of your minds. But it happens, then it ends, we talk, we go back to normal.”(Male 2, Couple 3). In addition, couples report some recurring dynamics of conflict resolution. In many cases, there is first an argument, followed by a brief period of withdrawal and, finally, a moment of dialogue and attempt of resolution: “We get into a quarrel, have the argument, and... so... there is one of us that usually commits more mistakes than the other. And then we withdraw a little and then we talk again, like this” (Man, Couple 2). Another possibility is that one of the spouses perceives the discomfort of the other with some situation and tries to talk about it.

Finally, some couples report that initially there is withdrawal and tension in relation to the topic of conflict until there is a natural release from the tension and the two interact again: “So, sometimes, we don’t .. due to a fight, we don’t talk, right? (...) when one turns to one side in bed, and the other to the other (laugh), and sleeps. Then one day goes by two days go by, until the needs of everyday life make you talk again” (Woman, Couple 8). The couples’ reports also show that one spouse often has an easier time approaching the other and starting the dialogue in an attempt to negotiate or resolve the conflict. With regard to decision making, the participants report that they talk about the different possibilities until they reach a consensus: “we see several places like this, one mentions a place, another mentions another, then we look at what one has, then what the other has and together we …(make a decision)”(Woman, Couple 7).

C.4. Respect for individuality and privacy. The participants valued the preservation of the individual space of each spouse in the relationship, respecting the space of the other and maintaining their own space, maintaining a certain degree of independence and investment in aspects other than just life as a couple: “respecting the space of the other. Cultivating your space, but also letting the other have their own space” (Man 2, Couple 3). However, there are also reports that indicate that individuality gets blurred due to the marriage and/or the family: “I will forget my own self and I will turn the page, and we will find the better side of the other because they (the children) need the father present, they need me present (...) the “me” ends up disappearing from the person’s life, right”(Woman, Couple 8). Finally, the theme also brings together contents that refer to the lack of privacy, in which the preservation of individuality is hampered by issues of physical space or the constant presence of the spouse: “this space of being alone, which is something I have always valued a lot, because I lived a long of time alone, too, it was kind of difficult” (Woman, Couple 2)

C.5. Ability to overcome crises and resilience. This theme covers the contents related to the perception of solidity, stability, and security of the relationship that result from moments of overcoming crises: “(the relationship) has become more solid than we imagined. Because that’s it, when we needed it most, we knew we could count on this stability factor” (Man, Couple 2). In the reports included in this theme, the participants refer to marriage as a safe base and emphasize the importance of the decision to continue in the relationship at the difficult moments they face: “I think that still as a whole, it is good to be married, it is good to have a family. It is good to have this base, this security... Having somewhere to go back to, do you understand?” (Woman, Couple 8).

C.6. Leisure as a couple. The moments of leisure and relaxation appear in the couples’ statements as important for maintaining the health of the relationship. Leisure includes moments when they can be at ease with each other and invest time in activities such as watching movies, cooking, dancing, camping, and traveling: “we like to cook, to travel, we like to go camping”( Woman 1, Couple 6); “Then the weekend comes, we get ready and... and go out to dinner. Like, that is a relief from the week... it’s good for us”(Woman, Couple 7); “Staying together, relaxed, without worrying about commitments and problems... trying to have fun... playing” (Man, Couple 1).

The adaptive processes axis presents itself as a central element in marital relations. Through these processes, spouses establish their relationship dynamics, accommodating individual aspects through coping with conflicts and building conjugality based on joint learning. This learning results from the couple’s coexistence and ability to articulate their resources to face moments of crisis, whether these crises are associated with the relationship or not. In this sense, it is essential that there are common goals to be achieved, for the couple to build their path in the same direction. Investment in leisure as a couple and respect for the individuality contribute to maintaining marital health, avoiding overburdening the relationship. Trust and mutual respect can be understood as necessary conditions for these processes to be established in an adaptive way.

D. Context Axis

The context axis covers factors external to the relationship, including elements belonging to the nuclear family or the extended family. These aspects appeared in questions about the couple’s history and both happy and difficult moments of the relationship. Couples point to the role of context as a trigger for stress in the relationship, but also as a source of support and a driver of changes.

D.1. Period of achievement of financial stability. Financial stability, including the couple’s and family’s income and money management, and material issues involving mainly the need for their own housing, was pointed out as an important factor by couples: “So until we build our house, the financial issue doesn’t allow us to leave and rent a place, so I’m stuck there” (Woman, Couple 4); “It is a matter of not having our own space. (…) We already realize that this creates a certain difficulty, that we cannot move forward, we cannot... impose or organize things our way” (Man 2, Couple 5). The reports included in this theme also deal with the financial management by couples and the positive impact of stability or increased income on the spouses’ daily lives: “this last (year) has been very good for me because... we have financial stability...”(Woman, Couple 1).

D.2. Labor Context. The work context seems to interact with the relationship in several ways. Overwork, the difficulty of coping with the demands of professional life, dissatisfaction with work, and the concern with unemployment are pointed out as ways of influencing this theme in the relationship: “I was unable to cope with my work, and I felt that I also left something to be desired in the relationship” (Man, Couple 2). The concern with work also appears as related to the need to provide for the family: “if you have a problem at work, it ends up giving you a certain fear of losing it and not being able to provide for, support the family. So, when there is a problem at work, it starts to bother you and, whether you like it or not, it gets into the house” (Man, Couple 8).

D.3. Unpredictable horizontal stressors. Unexpected events appeared as stressors at different moments in the marital trajectory. These stressors are the death or separation of family members, financial crisis, moments of transition and plans that could not be realized as expected for reasons beyond the couple: “this change, because it involves closing an apartment, closing things here, is leaving us a lot anxious” (Man, Couple 2). The financial crisis and unemployment appear prominently among these events: “our financial crisis started, and we sold the house, went to pay rent with two young children, and that was very difficult” (Woman, Couple 7).

D.4. Vertical stressors related to the family. This theme brings together contents related to the problems in the family of origin of one or both spouses. The participants report the impact of the events that happen in the families on the couple, the influence of family members who cohabit or live with the spouses day by day, and the existence of family conflicts: “And families, you know, I think families are always permeating the problems” (Man, Couple 1); “His mother doesn’t accept me (…) we don’t get along, so she does everything to keep the children away from me” (Woman, Couple 4).

D.5. Support from the family of origin. The support received by spouses from external sources, especially from the family, was highlighted by some participants: “The family too... the family is always there” (Woman, Couple 1). This support occurs in several ways, such as material assistance, help in the execution of daily tasks and emotional support: “I went out to work, she took care of them, or when they were sick I asked my mother for help. Or my sister also always came to help us out” (Woman, Interview 7).

D.6. Development of maturity. The participants also mentioned that the spouses’ maturity, which appears to be associated with age, is an important factor for the relationship: “I consider that I am a much better person today than I was back then, maturity, both of us met in our thirties” (Woman 2, Couple 6). Maturity, according to the participants, provides flexibility and emotional stability to the members of the couple: “I feel much more mature (…) affectivelly, emotionally, much more stable, because... I used to be much more insecure” (Male 2, Couple 5).

D.7. The family with children. The arrival of the children, in general, is pointed out as a moment of happiness and fulfillment of the dream of establishing a family: “we planned... and their arrival with health, exactly, even the way we thought they would come... their characteristics, so it was... wow, it was a lot of joy” (Woman, Couple 7). It also highlights the need to adapt to the demands and tasks inherent to raising children. Despite this, the presence of children is understood as generating gratification as parents perceive the success of transmitting their own values to their children and consider them as strengthening the marital bond: “Then when they begin to reward you for everything that you went through, I think it’s a very cool moment (...) we managed to pass the values on to them and they manage to keep them”(Woman, Couple 8). For remarried spouses, the importance of having a good relationship between the children and the new spouse for the success of the current relationship also appears: “He always treated my children very well, he always had affection for them, and they always realized that (…) this was very, very, very important to me”(Woman, Couple 4).

The context axis encompasses the couple’s surroundings, mainly with regard to financial, work and family life cycle factors. These factors interact with each other, as the period of financial achievement depends on the work context and often coincides with the development of maturity and the arrival of children. At these times, the support of the family of origin is essential to help the couple to meet the demands of this phase and unpredictable stressful events, without there being an excessive burden on the relationship. The family, however, can also present itself as a stressor, either due to the intrusion of the family of origin in the nuclear family or due to family issues that reverberate in the couple’s relationship.

Discussion

This study aimed at clarifying the marital quality construct, understood based on the Triangular Theory of Love (Sternberg, 1986), proposing dimensions that elucidate the intersection of themes related to the individual, the context and the adaptive processes, in the perspective of couples according to the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model (Karkey & Bradbury, 1995). With regard to marital quality, some of the themes identified as components of the construct in this study correspond to the Triangular Theory of Love, composed of decision/commitment, intimacy, and passion. This theory offers a comprehensive approach to romantic relationships, including emotional, cognitive, and motivational aspects. The decision/commitment component is similar to the theme Commitment and Investment in the Relationship identified in this study as it represents the cognitive commitment to the relationship and the decision and the clarity about what to expect from the relationship (Sternberg, 1986). However, this component, as identified in this study, also includes a behavioral aspect, referring to the commitment invested in the relationship and in providing support to the spouse for the relationship between the couple to develop.

As for the emotional aspect, the participants’ reports about intimacy and complicity were similar to Sternberg’s (1986) concept of intimacy, emphasizing the proximity between the couple and a familiarization that facilitates non-verbal communication. In this study, another emotional aspect was also identified as belonging to the marital quality: The Expression of Tenderness and Affection. This theme represents small daily actions in which the partners show affection, care, and concern for each other. These statements are especially important in the course of the relationship as they can compensate for the decline in passion and sexuality that usually occurs over time in marital relationships (Rizzon et al., 2013; Sternberg, 1986).

The theme Passion and Attraction for Spouses, in turn, received less emphasis in the interviews. This can be explained both by the difficulty in openly addressing this issue with a person outside the relationship, in order to protect the couple’s intimacy, and by the fact that this aspect becomes more secondary in the relationship over time, according to the literature (Rizzon et al., 2013; Sternberg, 1986) and to the interviewees themselves. The theme Marital Satisfaction is an aspect widely studied in the literature on marital relations, being a consensus as a component of the quality of the relationship (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Mosmann et al., 2006).

The adaptive processes axis represents a set of variables widely investigated in the literature, especially for behavioral theories, with regard to communication and conflict resolution (Baucom et al., 2015; Gottman, Driver, & Tabares, 2015). Nevertheless, other variables included in these processes are important and have been gaining space in recent literature. Leisure and time that the couple spends together, for example, have been pointed out in the Brazilian literature as factors related to the quality of the relationship and marital conflicts (Costa & Mosmann, 2015; Heckler & Mosmann, 2016; Mosmann & Falcke, 2011). In addition, a recent theoretical model of marital relationships proposes that spouses’ goals, especially shared goals, play an important role not only in the quality of the relationship, but also in the growth of the couple, particularly when the enrichment of the relationship is an end in itself. (Fowers & Owenz, 2010). The themes Common Goals and Planning and Joint Learning interact with each other in a coherent way with this model, as joint learning is associated with the way the couple is organized to achieve common goals, coexistence and coping with adversity according to the participants’ reports. One can think that, through these processes, a marital identity is also built from the exchanges between partners, from the construction of a history and common meanings, as already described in the Brazilian literature (Féres-Carneiro, 1998; Carneiro & Diniz-Neto, 2010). In this sense, it is possible to integrate not only the findings of this study in relation to the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model, but also the findings from the Brazilian literature and elements of recent models that aim at explaining couple relationships from this axis.

With regard to the individual, the importance of preserving individuality is highlighted in the couple’s speech, especially among the younger ones. This has been a trend pointed out in Brazilian literature for two decades (Féres-Carneiro, 1998). Despite this, individuality does not appear to be incompatible with the construction of a marital reality, but rather as a value to be preserved by the spouses, capable of strengthening the relationship, as these individual aspects continue to arouse new interests over time. Thus, for some couples, it seems that there is already an easier way to reconcile aspects of individuality and conjugality that previously seemed conflicting.

The individual characteristics brought by the spouses to the relationship to the relationship and the context in which the couple is inserted, including their surroundings, stressors, and available resources, seem to interact with the adaptive processes and the quality of the relationship. Individual characteristics can play a role in marital choice itself (Féres-Carneiro, 1987; 1997), in addition to guiding the processes that occur between the couple. Couples whose members have different values, for example, may have more conflicts related to this theme (Curtis & Ellison, 2002; Mahoney, 2005). Moreover, the way the couple resolves these conflicts may or may not be favored by the characteristics of the individual. One can think that personality traits such as agreeableness and openness facilitate communication and conflict resolution while characteristics related to inflexibility and emotional instability make these processes difficult (Vater & Schröder-Abé, 2015).

The similarity between the partners and the existence of common values also seems to play an important role in defining the couple’s goals and in managing the time they spend together. In fact, the perception of personality similarities between spouses is a factor related to satisfaction and success in the relationship (Barelds & Barelds-Dijkstra, 2007). Differences, understood as complementary, play an important role in defining certain roles taken by partners. Complementary features tend to offer a more diverse set of skills to perform the tasks that need to be accomplished by the couple. The literature documents that complementarity is especially important for middle-aged couples, since the demands of this phase are less oriented towards building a shared reality and intimacy between the couple, and more focused on fulfilling tasks such as raising children and supporting the family (Bohns et al., 2013; Shiota & Levenson, 2007).

These tasks also appear as a relevant factor for conjugality, grouped in the Context axis. In this axis, financial and material issues played an important role, being also related to marital satisfaction, as also mentioned in the international literature, especially in couples of lower socioeconomic level (Maisel & Karney, 2012). Along with economic issues, work also impacts on conjugality, especially on dual career couples (Heckler & Mosmann, 2016). This impact, however, can be mitigated by the way the partners deal with the demands of the job. For example, there is evidence that the ability to optimize resources such as time, money, and energy contributes to improving individual and marital functioning in several areas (Unger, Sonnentag, Niessen, & Kuonath, 2015).

Thus, factors associated with the context can reverberate in the adaptive processes in both negative and positive ways. Financial difficulties and unexpected events can increase tension between the couple and make it difficult to plan and achieve goals, for example. Facing these situations, however, can bring growth and learning to the relationship, and often with the support of the context itself, in the form of family and social support.

This may explain the fact that couples often refer to unexpected events as promoters of the couple’s learning and growth, even though these stressors require investment of time and energy. Horizontal stressors are already described in the literature as context factors that are part of the family life cycle, responsible for increasing family tension in unexpected events or transition points (McGoldrick & Shibusawa, 2016). The existence of external support at these times, especially from the family, was also pointed out as relevant in this confrontation. Although horizontal stressors are often associated with a decreased capacity for constructive interactions between the couple (Helms et al., 2014; Ledermann, Bodenmann, Rudaz, & Bradbury, 2010; Maisel & Karney, 2012), it is possible that this effect is mitigated and that these situations are used in favor of marital development. This understanding is fundamental for working with couples, as it indicates that the promotion of the ability to cope with stress by partners and the strengthening of support networks for the couple can be complementary tools to the training of interaction skills to improve the quality of the relationship.

The children, for the couples who have them, were understood as the realization of a life project that begins with the birth of the children and culminates in the transmission of the couple’s values to the next generation, which also appears in previous records in the Brazilian literature (Costa & Mosmann, 2015). The moment of the children’s arrival is marked by happiness, but also by the need to meet new demands, often needing the support of the extended family. In this sense, children interact with other contextual factors, whether due to the greater need to approach the families of origin and support for the couple during a period of adaptation and intense demands, the need for financial reorganization, or the motivation to seek better material conditions. to provide quality education and comfort to children. In this way, as well as other contextual factors, children can represent both a source of stress and weariness in the marital relationship, as well as improving the family environment and living conditions in the family. Factors such as the perception of high parental self-efficacy, the existence of a co-parenting alliance (Kwan, Kwok, & Ling, 2015) and external support are important for the parental couple to maintain good marital quality.

These results, taken as a whole, are in agreement with the predictions of the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Model that couples who have effective adaptive processes, face less stressful contexts and have favorable individual characteristics, should present higher quality relationships (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). In addition, these results are in accordance with previous national literature (Costa & Mosmann, 2015; Heckler & Mosmann, 2016; Scheeren, Vieira, Goulart, & Wagner, 2014; Wagner, Mosmann, Scheeren, & Levandowski, 2019), indicating the utility of the model to integrate the findings of these studies into a coherent set. Although comparing couples with different levels of marital quality is beyond the scope of this study, the participants’ statements demonstrate the central role of adaptive processes in the relationship between the various identified themes.

Adaptive Processes seem to function as intermediaries between the Context and the Individual axes and the Marital Quality axis, as the characteristics of the spouses and the context in which they are inserted tend to reverberate in the marital quality from the interaction processes between the couple. Thus, it can be thought that the individual and the contextual aspects reverberate in the relational processes that occur between the couple through coping with conflicts, and the establishment of common goals between the couple, for example. These processes, in turn, reverberate in the quality of the relationship. For example, the existence of trust and the ability to approach each other and have a dialogue can favor both the expression of affection and intimacy, whereas the latter can facilitate non-verbal expression. Likewise, planning processes and common objectives add a long-term perspective to the relationship, which can contribute to investment and a sense of commitment to the relationship. This finding is supported by findings from Brazilian and international studies (Ghana, Saada, Broc, Kolec, & Cazauvieilh, 2016; Hardy, Soloski, Ratcliffe, Anderson, & Willoughby, 2015; Scheeren et al., 2014).

The relationship between individual, context and adaptive processes can be considered in terms of the tasks that the couple needs to perform throughout the relationship. In general terms, these tasks would be to accommodate the individual characteristics and desires of each member of the dyad in a shared marital reality (Féres-Carneiro, 1998) and dealing with the demands presented by the context, such as the emergence of financial instability, job and housing changes and the birth of children. The way the couple deals with these tasks can be understood, according to the criteria adopted in this study, as adaptive processes. In this sense, it is possible to evaluate some aspects of the marital relationship to verify how these processes occur and their reverberation in the quality of the relationship. These aspects may include, for example, how the couple communicates to accommodate their characteristics and how to resolve the differences that arise in the process; the way they reconcile each spouse’s life goals in joint planning; and the administration of these tasks in their available free time, also saving space for leisure. Leisure, in its own turn, brings the couple closer and contributes to the construction and maintenance of intimacy.

In perspective, the way the couple addresses these issues outlines the marital quality in its different dimensions throughout the relationship. It is expected, for example, that the need to face such demands together will generate a willingness to invest and commit to the relationship. Thus, these adaptive processes can also bring the couple closer together, generating a sense of belonging, creating a shared reality, and fostering intimacy between spouses. This intimacy, together with the ability to communicate, should allow the expression of affection and sexuality between the couple.

Thus, intervening in adaptive processes seems to be an effective way to promote marital quality. These processes are more easily modifiable as they consist of skills that can be trained and also taught to couples (Halford, Markman, Kline, & Stanley, 2003). For this reason, they are an important way of working both in the clinic and in interventions to promote marital health.

Final considerations

This study confirms the importance of individual characteristics, context, and adaptive processes when considering the quality of the relationship. The results demonstrated how a theoretical model proposed in the international context is presented in the perception of the couples investigated in this study. The results obtained are consistent with the model, indicating which aspects stand out in the local context and how findings from Brazilian studies can be integrated into the perspective proposed by the theoretical model. Thus, one of the main contributions of this study was the proposal of relevant dimensions for the conceptualization of marital quality through the understanding of the data on couples from the perspective of the Vulnerability Stress Adaptation Model.

In terms of practical implications, the fact that adaptive processes assume a central role indicates that it is important to invest in these aspects when working with couples, especially considering that adaptive processes are more easily modifiable when compared to the context and individual aspects. In addition, contextual aspects that present themselves as stressors to partners may be used in a constructive way, favoring adaptive processes and, thus, increasing marital quality. It is possible that education on strategies to deal with stress is a way of promoting not only individual but also marital health, so that the change in one of the partners reverberates in the marital subsystem.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the limited sample size did not allow to cover all the diversity of life cycle phases and possible marital and family configurations. Although the sample profile was heterogeneous in terms of marital status, length of the relationship and sexual orientation, a horizontal data analysis was used in this study. Those specificities of the sample were not explored, once the aim was to identify topics relevant to marital quality in general. Thus, there was the intent of diversifying as much as possible the characteristics of the interviewed couples, and it was possible to identify many common processes that overlap differences. In addition, the theme studied involves values and social desirability, which may have somehow influenced the reports obtained in the interviews. Likewise, some themes such as sexuality could be explored only superficially. The couples interviewed in the pilot phase pointed out that, although this is a relevant topic, spouses do not feel comfortable to openly address sexuality in a research context, with someone outside the relationship with whom there is little intimacy.

Based on the results obtained, it is important that future studies continue to analyze the relationships proposed by the model investigated in this study. New studies could investigate how the aspects discussed are manifested in samples with different characteristics from the couples interviewed in this study and in other regions of Brazil. In addition, quantitative studies investigating whether these findings can be generalized to broader populations are needed to deepen the knowledge about marital relationships in the Brazilian context.

REFERENCES

Barelds, D. P. H., & Barelds-Dijkstra, P. (2007). Love at first sight or friends first? Ties among partner personality trait similarity, relationship onset, relationship quality, and love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(4), 479-496. doi: 10.1177/0265407507079235 [ Links ]

Baucom, B. R., Dickenson, J. A., Atkins, D. C., Baucom, D. H., Fischer, M. S., Weusthoff, S., Hahlweg, K., & Zimmerman, T. (2015). The interpersonal process model of demand/withdraw behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 80-90. doi: 10.1037/fam0000044 [ Links ]

Bohns, V. K., Lucas, G. M., Molden, D. C., Finkel, E. J., Coolsen, M. K., Kumashiro, M., Rusbult, C. E., & Higgins, E. T. (2013). Opposites fit: Regulatory focus complementarity and relationship well-being. Social Cognition, 31(1), 1-14. doi: 10.1521/soco.2013.31.1.1 [ Links ]

Borges, C. C., Magalhães, A. S., & Féres-Carneiro, T. (2014). Liberdade e desejo de constituir família: Percepções de jovens adultos. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 66(3), 89-103. [ Links ]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Conselho Nacional de Saúde (2012). Resolução nº 466/2012 - Dispõe sobre pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos. Brasil: Ministério da Saúde, Brasília, DF. [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., & Mosmann, C. (2015). Relacionamentos conjugais na atualidade: Percepções de indivíduos em casamentos de longa duração. Revista da SPAGESP, 16(2), 16-31. [ Links ]

Coutinho, S. M. S., & Menandro, P. R. M. (2010). Relações conjugais e familiares na perspectiva de mulheres de duas gerações: “Que seja terno enquanto dure”. Psicologia Clínica, 22(2), 83-106. doi: 10.1590/S0103-56652010000200007 [ Links ]

Curtis, K. T., & Ellison, C. G. (2002). Religious heterogamy and marital conflict. Journal of Family Issues, 23(4), 551-576. doi: 10.1177/0192513x02023004005 [ Links ]

Delatorre, M. Z., & Wagner, A. (2020). Marital quality: reviewing the concept, instruments, and methods. Marriage & Family Review, 56(3), 293-216. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2020.1712300 [ Links ]

Féres-Carneiro, T. (1987). Aliança e sexualidade no casamento e no recasamento contemporâneo. Psicologia Teoria e Pesquisa, 3(3), 250-261. [ Links ]

Féres-Carneiro, T. (1997). Escolha amorosa e relação conjugal na homossexualidade e na heterossexualidade: um estudo sobre namoro, casamento, separação e recasamento. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 10(2), 351-368. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79721997000200012 [ Links ]

Féres-Carneiro, T. (1998). Casamento contemporâneo: O difícil convívio da individualidade com a conjugalidade. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 11(2), 379-394. doi: 10.1590/S0102-79721998000200014 [ Links ]

Féres-Carneiro, T., & Diniz-Neto, O. (2010). Construção e dissolução da conjugalidade: Padrões relacionais. Paidéia, 20, 269-278. doi: 10.1590/S0103-863X2010000200014 [ Links ]

Fincham, F. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (1987). The assessment of marital quality: A reevaluation. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49(4), 787-809. doi: 10.2307/351973 [ Links ]

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., & Thomas, G. (2000). The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 340-354. doi: 10.1177/0146167200265007 [ Links ]

Fowers, B. J., & Owenz, M. B. (2010). A Eudaimonic theory of marital quality. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2, 334-352. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00065.x [ Links ]

Gana, K., Saada, Y., Broc, G., Koleck, M., & Cazauvieilh, C. (2016). Dyadic cross-sectional associations between negative mood, marital idealization, and relationship quality. The Journal of Psychology, 150(7), 897-915, doi: 10.1080/00223980.2016.1211982 [ Links ]

Gottman, J. M., Driver, J., & Tabares, A. (2015). Repair during marital conflict in newlyweds: How couples move from attack-defend to collaboration. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 26(2), 85-108. doi: 10.1080/08975353.2015.1038962 [ Links ]

Halford, W. K., Markman, H. J., Kline, G. H., & Stanley, S. M. (2003). Best practice in couple relationship education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(3).385-406. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01214.x [ Links ]

Hardy, N. R., Soloski, K. L., Ratcliffe, G. C., Anderson, J. R., & Willoughby, B. J. (2015). Associations between family of origin climate, relationship self-regulation, and marital outcomes. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(4), 508-521. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12090 [ Links ]

Heckler, V. I., & Mosmann, C. P. (2016). A qualidade conjugal nos anos iniciais do casamento em casais de dupla carreira. Psicologia Clínica, 28(1), 161-182. [ Links ]

Helms, H. M., Supple, A. J., Su, J., Rodriguez, Y., Cavanaugh, A. M., & Hengstebeck, N. D. (2014). Economic pressure, cultural adaptation stress, and marital quality among Mexican-Origin couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 77-87. doi: 10.1037/a0035738 [ Links ]

Heyman, R. E., Sayers, S. L., & Bellack, A. S. (1994). Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology, 8(4), 432-446. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.8.4.432 [ Links ]

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3- 34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3 [ Links ]

Knapp, S. J., & Lott, B. (2010). Forming the central framework for a science of marital quality: An interpretive alternative to marital satisfaction as a proxy for marital quality. Journal of Family & Theory Review, 2, 316-333. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00064.x [ Links ]

Kwan, R. W. H., Kwok, S. Y. C. L., & Ling, C. C. Y. (2015). The moderating roles of parent self-efficacy and co-parenting alliance on marital satisfaction among Chinese fathers and mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3506-3515. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0152-4 [ Links ]

Ledermann, T., Bodenmann, G., Rudaz, M., & Bradbury, T. N. (2010). Stress, communication, and marital quality in couples. Family Relations, 59, 195-206. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00595.x [ Links ]

Lomando, E., Wagner, A., & Gonçalves, J. (2011). Coesão, adaptabilidade e rede social no relacionamento conjugal homossexual. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 13(3), 95-109. [ Links ]

Mahoney, A. (2005). Religion and conflict in marital and parent-child relationships. Journal of Social Issues, 61(4), 689-706. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00427.x [ Links ]

Maisel, N. C., & Karney, B. R. (2012). Socioeconomic status moderates associations among stressful events, mental health, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(4), 654-660. doi: 10.1037/a0028901 [ Links ]

McGoldrick, M., & Shibusawa, T. (2016). O ciclo vital familiar. In F. Walsh (Org.), Processos normativos da família: Diversidade e complexidade (pp. 375-398). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Meletti, A. T., & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2015). Conjugalidade e expectativas em relação à parentalidade em casais homossexuais. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática , 17(1), 37-49. doi: 10.15348/1980-6906/psicologia.v17n1p37-49 [ Links ]

Mônego, B. G., & Teodoro, M. L. M. (2011). A teoria triangular do amor de Sternberg e o modelo dos cinco grandes fatores. Psico-USF, 16(1), 97-105. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712011000100011 [ Links ]

Mosmann, C., & Falcke, D. (2011). Conflitos conjugais: Motivos e frequência. Revista da SPAGESP , 12(2), 5-16. [ Links ]

Mosmann, C., Wagner, A., & Feres-Carneiro, T. (2006). Qualidade conjugal: Mapeando conceitos. Paidéia, 16(35), 315-325. doi: 10.1590/S0103-863X2006000300003 [ Links ]

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45,141-151. doi: 10.2307/351302 [ Links ]

Rizzon, A. L. C., Mosmann, C. P., & Wagner, A. (2013). A qualidade conjugal e os elementos do amor: Um estudo correlacional. Clínicos, 6(1), 41-49. doi: 10.4013/ctc.2013.61.05 [ Links ]

Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140-187. doi: 10.1037/a0031859 [ Links ]

Rosado, J. S., & Wagner, A. (2015). Qualidade, ajustamento e satisfação conjugal: Revisão sistemática da literatura. Pensando Famílias, 19(2), 21-33. [ Links ]

Scheeren, P., Vieira, R. V. A., Goulart, V. R., & Wagner, A. (2014). Marital quality and attachment: The mediator role of conflict resolution styles. Paidéia, 24(58), 177-186. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272458201405 [ Links ]

Scorsolini-Comin, F., & Santos, M. A. (2010). Satisfação conjugal: Revisão integrativa da literatura científica nacional. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26(3), 525-532. doi: 10.1590/S0102-37722010000300015 [ Links ]

Shiota, M. N., & Levenson, R. W. (2007). Birds of a feather don’t always fly farthest: Similarity in big five personality predicts more negative marital satisfaction trajectories in long-term marriages. Psychology and Aging, 22(4), 666-675. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.666 [ Links ]

Silva, I. S., & Frizzo, G. B. (2014). Ter ou não ter? Uma revisão da literatura sobre casais sem filhos por opção. Pensando Famílias, 18(2), 48-61. [ Links ]

Silva, P. O. M., Trindade, Z. A., & Silva Junior, A. (2012). As representações sociais de conjugalidade entre casais recasados. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 17(3), 435-443. doi: 10.1590/S1413-294X2012000300012 [ Links ]

Spanier, G. B., & Cole, C. L. (1976). Toward clarification and investigation of marital adjustment. Journal of Sociology of the Family, 6, 121-146. [ Links ]

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119-135. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119 [ Links ]

Stroud, C. B., Meyers, K. M., Wilson, S., & Durbin, C. E. (2015). Marital quality spillover and young children’s adjustment: Evidence for dyadic and triadic parenting as mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(5), 800-813. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.900720 [ Links ]

Unger, D., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Kuonath, A. (2015). The longer your work hours, the worse your relationship? The role of selective optimization with compensation in the associations of working time with relationship satisfaction and self-disclosure in dual-career couples. Human Relations, 68(12), 1889-1912. doi: 10.1177/0018726715571188 [ Links ]

Vater, A., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2015). Explaining the link between personality and relationship satisfaction: Emotion regulation and interpersonal behaviour in conflict discussions. European Journal of Personality, 29, 201-215. doi: 10.1002/per.1993 [ Links ]

Wagner, A., Mosmann, C. P., Scheeren, P., & Lvandowski, D. C. (2019). Conflict, conflict resolution and marital quality. Paidéia , 29(e2919). doi: 10.1590/1982-4327e2919 [ Links ]

Funding: This work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Financing Code 001

How to cite: Delatorre, M. Z., & Wagner, A. (2021). The marital relationship from the perspective of couples. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(1), e-2355. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i1.2355

Correspondence: Marina Zanella Delatorre, e-mail: marina_mzd@yahoo.com.br; Adriana Wagner, e-mail:adrianaxwagner@gmail.com. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2600 - Sala 126, Porto Alegre-RS, Brasil CEP: 90035-003

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M.Z.D. has contributed in a,b,c,d; A.W. in a,e.

Received: August 06, 2019; Accepted: October 20, 2020

texto em

texto em

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI