Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 18-Sep-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2322

Original articles

Social representations of the body for people with physical disabilities

1 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Brasil

The body is essential in forming impressions on someone. When thinking about people with physical disabilities, the body becomes the main marker of difference. In the theoretical foundation of this research, the Theory of Social Representations was used. The objective was to characterize the social representations of the body for 12 men and 12 women with acquired physical disabilities. Semi-structured interviews and a sociodemographic questionnaire were used as instruments. The data were analyzed through Descending Hierarchical Classification and descriptive analysis. The social representations of the body presented two structural axes: health and aesthetics. No significant differences were found in the social representations of the body of men and women. However, some experiential elements were distinct, evidencing maintenance of behavior related to gender roles. It is pertinent to create public spaces that are attentive to the corporal diversity and strategies that stimulate the social and political participation of people with disabilities.

Key words: social representation; body; physical disability; people with disabilities

O corpo é essencial na formação de impressões sobre alguém, ao se pensar em pessoas com deficiência física, o corpo torna-se o principal marcador da diferença. Na fundamentação teórica dessa pesquisa utilizou-se a Teoria das Representações Sociais e objetivou-se caracterizar as representações sociais do corpo para 12 homens e 12 mulheres com deficiência física adquirida. Como instrumentos utilizou-se entrevista semiestruturada e questionário sociodemográfico. Os dados foram analisados através de Classificação Hierárquica Descendente e análise descritiva. As representações sociais do corpo apresentaram dois eixos estruturais: saúde e estética. Não foram encontradas diferenças significativas nas representações sociais do corpo de homens e mulheres, contudo, alguns elementos vivenciais foram distintos, evidenciando manutenção de comportamento relacionado aos papeis de gênero. Mostra-se pertinente a criação de espaços públicos que se atentem à diversidade corporal e estratégias que estimulem a participação social e política das pessoas com deficiência.

Palavras-chave: representação social; corpo; deficiência física; pessoas com deficiência

El cuerpo es esencial en la formación de impresiones sobre alguien, al pensar en personas con discapacidad física, el cuerpo se convierte en el principal marcador de la diferencia. En la fundamentación teórica se utilizó la Teoría de las Representaciones Sociales, se objetivó caracterizar las representaciones sociales del cuerpo para 12 hombres y 12 mujeres con deficiencia física adquirida. Como instrumentos se utilizó entrevista semiestructurada y cuestionario sociodemográfico, los datos fueron analizados a través de clasificación jerárquica descendente y análisis descriptivo. Las representaciones sociales del cuerpo presentaron dos ejes estructurales: salud y estética. No se encontraron diferencias significativas en las representaciones sociales del cuerpo de hombres y mujeres, sin embargo, algunos elementos fueron mantenimiento existencial distinto del comportamiento relacionado con papel de género. Se muestra pertinente la creación de espacios públicos que se atenten a la diversidad corporal y estrategias que estimulen la participación social y política de las personas con discapacidad.

Palabras clave: representación social; cuerpo; medios de comunicación; discapacidad; personas con discapacidad

There are several concepts related to the body ranging from physical aspects to imaginary aspects. This study uses the definition proposed by Andrieu (2006) which defines the body as a genetic program that develops from a greater or lesser biocultural plasticity. In Brazil, there are around 45 million Brazilians with some degree of disability (IBGE, 2011), representing 23.9% of the total population. Among them, 13 million have serious impairments. People with disabilities are considered as those who have, in the long term, impairments of a physical, intellectual, or sensory nature that, when interacting with various barriers, interrupt full participation in society when compared to the condition of other people (I Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities, 2007). Data from IBGE (2011) show that 1.3% of the Brazilian population has some type of physical/motor disability, and of these, almost half (46.8%) have an intense or very intense degree of limitations.

Concerning physical disability, the body is the principal difference marker. However, it is important to point out that the idea of a perfect and complete body is utopian as contemporary society increasingly establishes restricted and idealized standards (Meurer & Gesser, 2008). Unattainable beauty standards contribute to the discrimination of people with physical disabilities due to the stereotypes that guide the population’s relations with the “different” body. Thus, physical appearance, represented in the body as a social object, is characterized as a privileged context for the study of the interaction between individual and collective aspects, because it emerges as a mediator of the social place and social relations established by people (Jodelet, 2017; Jodelet et al., 1982) relating to the processes of social categorization (Justo, Camargo & Bousfield, 2020).

The Social Representations Theory (SRT), developed by Moscovici (1961/2012), presents social representations as socially shared forms of knowledge of the world, which provide meaning to new or unknown facts, contributing to the formation processes of social communications. With a dynamic character, social representations are a network of beliefs, metaphors, behaviors, and images that articulate in a fluid way (Camargo et al., 2011), associating themselves with a notion that, according to Arruda (2015), refers to the social imaginary.

Beginning with Jodelet’s study (1984, 1986, 1994), researchers have dedicated themselves to the knowledge of the body’s social representations, relating them to aspects such as image, aging, aesthetics, health, among others. However, studies that relate the body’s social representations for people with physical disabilities are hardly found (Agmon, Sa’ar, & Araten-Bergman, 2016; Jones et al., 2015).

In this context, aspects of social representations regarding the body have significant differences between men and women. Generally, women have less self-esteem, less body satisfaction, and greater social and media pressure regarding aesthetic aspects (Camargo, Justo, & Aguiar, 2008; Castilho, 2001; Furtado, 2009). Understanding the differences between genders will contribute to the comprehension of the variables that influence the formation of social representations in the context of the body as a social object.

Specifically, regarding how people with disabilities are generally represented, women are seen as passive, vulnerable, and dependent - a fragile and innocent figure who must be rescued by a “capable” man, while men with disabilities are seen as powerless and unable to love (Barnes & Mercer, 2001). It is understood that, due to this social context, men and women with disabilities experience the body in different ways.

According to Mello and Nuernberg (2012), the phenomenon of physical disability does not stop at the body itself, but in the production of a culture and society that determines certain body variations as inferior, incomplete, or even in need of repair when viewed from a body normativity perspective.

Mello, Nuernberg, and Block (2014) refer to the emergence of the Social Model of Disability as a contraposition to the Medical Model of Disability, which is guided by the idea of healing or medicalizing the disabled body. The Social Model implies viewing disability beyond the body as the interaction of this person with their social and environmental surroundings. This way, the “problem” with disability becomes structural and social since it is society that does not embrace diversity by imposing various barriers on people.

Apart from the theoretical references presented, this study aims to characterize the social representations of the body for men and women with acquired physical disability.

Method

The present research is an indirect observation study with a qualitative approach of an exploratory, descriptive, and comparative nature, with a cross-sectional design. (Gil, 2008; Sampieri, Collado, & Lúcio, 2013). Case studies were used to investigate in depth the objects of the research (Yin, 2001). There were 24 participants with acquired physical disabilities in the age group of youths and young adults1, paired by sex, living in the Greater Florianopolis region. The choice in the number of participants followed the criteria of data saturation (Ghiglione & Matalon, 1993).

The data collection tool consisted of a semi-directive interview script for contents related to the body and physical disability and a sociodemographic questionnaire. The participants were accessed through the snowball sampling technique (Flick, 2009). The first participant was accessed out of convenience, starting from the researcher’s relations network.

The information obtained in the interviews related to the body and physical disability were organized into a single textual corpus and analyzed through Descending Hierarchical Classification (CHD) with the software IRaMuTeq (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnariores). The CHD aims to create text segment classes containing similar, but at the same time, different vocabularies from the text segments of other classes (Camargo & Justo, 2013). In the field of social psychology, particularly in social representation studies, the classes generated by the software may indicate social representations or aspects of it, in view of the importance given to linguistic manifestations (Veloz, Nascimento-Schulze & Camargo, 1999).

To compare the representations of the men and women participants, an analysis of specificities was conducted, also using the software IRaMuTeQ. This resource, also known as contrast analysis, allows the researcher to associate text segments with chosen variables (Camargo & Justo, 2013). In this study, the variable was sex. Moreover, to characterize the sample, descriptive statistical analysis (mean, standard deviation, and frequency) was performed using the software Statistical Package for Social Science - SPSS, version 17.0.

The project number 2.008.560 obtained approval from the UFSC Human Research Ethics Committee. Also, the research respects the confidentiality of the participants, and their participation was voluntary, through the signing of the Term of Free and Informed Consent - TCLE.

Results

Twelve men and twelve women with acquired physical disabilities between the ages of 20 and 52 (M= 36 years and 36 months; SD= 9 years and 7 months) participated. The majority had paraplegia (15), five had tetraplegia, three had amputations of a lower limb, and one had paresis. The average time of acquisition of the disability was 12 years and 1 month (SD= 9 years).

In addition to the open questions related to the body, the principal objective of the study, the participants were questioned about physical disability, thus aiming at understanding how these phenomena are articulated. The 24 interviews were transcribed and organized into a single bi-thematic textual corpus of body and disability, composing the analysis material. Each interview was identified by a line of command with the variables: sex and type of physical disability. When submitting the corpus to CHD, the material was divided into 24 texts with a total of 3.013 text segments, of which 90.54% were retained in the analysis

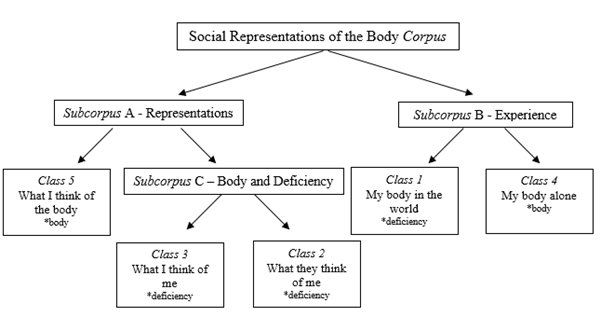

The corpus was divided into five content classes. Firstly, the CHD divided the corpus into two subcorpora, differentiating Classes 1 and 4 from the other classes. Then the second subcorpora was partitioned, separating Class 5 from Classes 3,1, and 2, which in turn were also separated into two parts, giving rise to Class 3 and finally Classes 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows the classes originated by CHD and named manually.

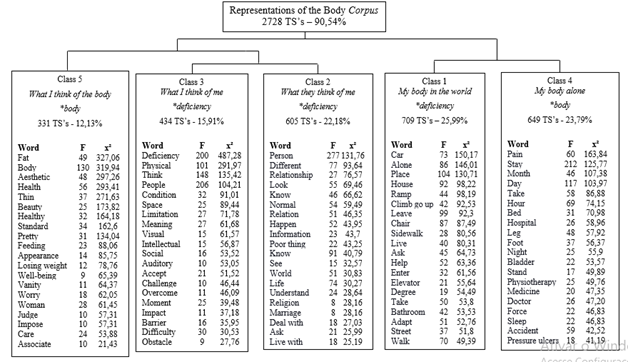

Figure 2 shows the classes together with their respective characteristic words, frequency, and chi-square. The 20 words with the highest association to the class were listed, this cutoff point aimed to demonstrate the most representative elements of each class. The association was verified through the chi-square test, a value of χ2 from 3.84 being considered significant when the parameters of the chi-square distribution in a table with a degree of freedom equal to 1 and a p-value equal to .05 were considered significant.

The first subdivision is separated from the rest of the corpus, “Experience”, generated Classes 1 and 4, and reports on the experiences of the interviewees related to injury and the condition of disability. Class 1 corresponds to 25.99% of the text segments and was entitled “My body in the world”; the segments are associated with the questioning about disability. The reports evidenced how accessibility can facilitate or hinder access to spaces and a common life. Having an adapted car appears as an element of autonomy and a facilitator for access to work since public transportation does not provide access to all places:

I go out by car, I get around well by car, I keep the chair, I am able to circulate well by car. But I only go from here to my work, from here to the mall, from here to the supermarket, you just can’t go anywhere. (Participant 22, female)

Dissatisfaction with the quality of the roads appears as common content among the interviewees because even if there are ramps, most of them do not allow for safe circulation with the wheelchair due to irregularities. In addition, they report the activities they carry out alone and those they need to request help for. It is possible observe the relationship between a higher degree of dependence and greater dissatisfaction with the act of requesting or needing help:

But it’s not a very easy thing, no matter what the disability, there will always be something making life difficult. Sometimes you can’t go out by yourself, you can’t do such a thing by yourself, you always have to be in need of help. It’s not a very easy thing, no, in fact, we need the will of others. (Participant 20, female).

Class 4, named “My body alone”, corresponds to 23.79% of the text segments. Its contents are characteristic of the questioning about the body; above all, they convey the new body relations after the acquisition of the disability. The segments show the relationship with the body mainly in the health aspects. Pain appears as a crucial factor in life, being constant and limiting. The text segments of this class show the intended routine for recovery and hospitalization in the hospital environment; they also refer to the rehabilitation and adaptation process.

The experience with the post-injury body also showed a routine of medicines, medical visits, and physiotherapy needs for the maintenance of functionality and physical well-being, body care preventing injuries and bedsores. Above all, many participants stated the difficulties they face because of the neurogenic bladder, and the lack of urination control that it brings limitations due to the necessary probes every hour and the public spaces that do not have accessible toilets, generating embarrassing situations - as demonstrated in the following excerpt:

There is always urine leakage and I have to use a diaper, this doesn’t bother me either, but it ends up being an impediment. I can’t go to the bathroom, the bladder bothers me, being disabled doesn’t, the neurogenic bladder does. (Participant 18, female)

A second subdivision, named “Representation,” distinguished Class 5 from the third subdivision “Body and Disability.” Class 5 represents 12.13% of the total and was entitled “What I think of the body” since its content contains representations related to a standard, non-disabled body. The words fat, body, aesthetic, health, thin, beauty are those that associated with class and the text segments contain the imposition of an aesthetic standard about the body, a social norm, with the fat person being the one who most flees from the norm of beauty, and with the woman the most charged.

But it seems to me that the current pattern is focused on thin, ripped, for both men and women. If you are thin, but not ripped and not healed, you still pass, but the fat one becomes a reference point. When you go to indicate something, it is there near that fat one there. (Participant 04, male)

The Class 5 segments show that sometimes body care is relative to health and sometimes to aesthetics, and often beautiful is associated with healthy. However, when linked to aesthetics it refers to the social context, and in the individual, it is liked to health. Some participants cited the need to remain thin to facilitate the use of the wheelchair and its transportation. Weight maintenance occurs through physical activities and food re-education. Still, in this context, dissatisfaction with body weight was mentioned, since it is something that can be modified - unlike disability. The following excerpt illustrates this context:

Especially because it can have deformities and a multitude of things, I started to worry about the body not for aesthetic reasons, but for health reasons. (Participant 19, female)

The third subdivision, named “Body and Disability” contains relations of the body with the condition of the person with disability and originated Classes 3 and 2. Class 3, entitled “What I think of me” corresponds to 15.91% of the text segments. Its contents mainly highlight the representation of the very condition of a person with a physical disability and exhibit perceptions of the disability as a whole. Although they have the perception that they are normal people, they express the limitations and challenges they deal with in the face of the obstacles they encounter socially:

Afterward, life moves on and becomes natural, normal. Then it becomes like other people who have no disabilities, it becomes natural. It is an adaptation; you change your way of thinking. (Participant 01, male)

There is this normality imposed by medicine that society says what is normal and abnormal, but I think the physical disability is more related to the issue of access, of you not being able to go somewhere. (Participant 18, female)

Class 2 corresponds to 22.18% and was named “What they think of me”, which also contains elements of the condition of a person with a disability, but how they are viewed socially. They report the lack of information people have about disability, creating erroneous stereotypes, and reinforcing the view of disability and pity.

The people look at you and they ask: What happened? Oh, you poor thing! Society has a lot of prejudice. Just because a person is in a wheelchair or doesn’t have a leg or an arm, doesn’t mean they are not capable. They are a person just like the others, only with some difficulties, but just like the others. Society doesn’t see, many people ask: Does she live alone? Does she make food? How can she do it by herself? How can she clean the house? (Participant 24, female)

Class 2 also highlights personal relationships after injury, especially amorous relationships. The men reported that they do not see much difference in how they have interacted lovingly before or after injury; they have maintained their relationships or created new ones and understand that women are more accommodating to body variations. Conversely, most women reported having difficulty creating new relationships because they do not correspond to male patterns of relationships and sexuality, and they are not seen as susceptible to motherhood. The following excerpts illustrate this context:

Relationships are cool, good. But it is more common for you to see women without a disability with men who have a disability than the contrary. It’s not that I haven’t seen it, but that is more common. (Participant 05, male)

I think men often judge women who have this type of disability as asexual; it has nothing to do with it, but it has this stereotype. But they don’t imagine the person having sex, so they don’t think about the possibility anymore because they don’t want a relationship without sex, and they can’t imagine that it is possible. (Participant 22, female)

When questioned about the body and physical disability, the participants reported their own personal experiences. The representations about the body were established on two pillars: the body with disability and the body without disability, with the latter seen from two points: those who have and do not have a body injury.

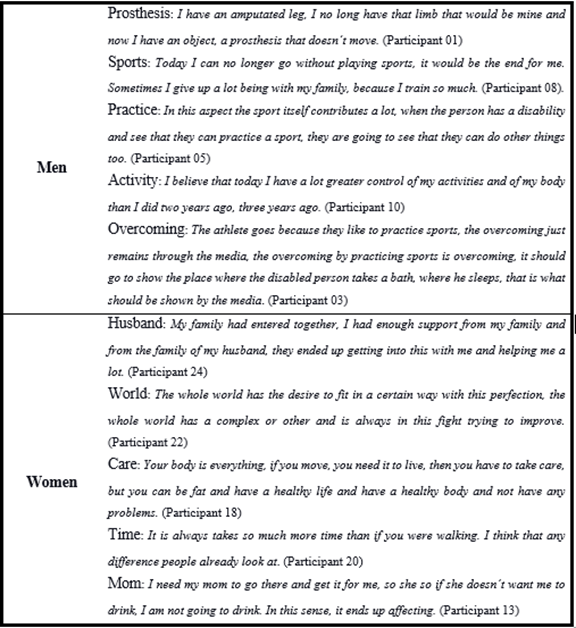

To conclude directly comparing the differences between men and women, the specificities were analyzed, allowing for direct verification of the association of the corpus vocabulary with the descriptive variable sex. Figure 3 shows the main words associated with each group and a respective text follow-up to contextualize them.

Through the contrast analysis, it was identified that men and women have particularities when relating to the body. The men highlighted content belonging to the practice of sports and the related aspects of overcoming this, physical activities, and the return to routine activities. The reports indicate that physical activities provide greater performance and quality in their daily activities since they strengthen their musculature, in addition to enabling socialization among peers as a crucial factor in informing the (im)possibilities in the face of injury. Still, the word prosthesis was also associated with men, possibly by the interviewees who suffered amputations being male. In this sense, they consider it as a fundamental tool for the quality of life and ease of locomotion.

In the contents expressed by the women, it can be seen that the body is linked to personal relationships lived. The husband appeared as a fundamental agent for the assistance of activities and care with the family. The importance of a companion who shares taking care of the children emerged to make maternity possible. Actions of body care, home, and family were mentioned, as well as the care that some receive from their mothers after injury, evidencing the female assignment of this function. The relationship with the lack of time for activities, such as getting together with friends or physical exercise, and the greater time they take to complete routine tasks were also characteristic. Men and women did not present significant differences in the aspects of social representations stated by the dendrogram classes, however, with the analysis of specificities, different experiences were identified in relation to the condition of disability, demonstrating the retention of behaviors related to gender roles.

Discussion

The analysis of the corpus allowed for the verification of two central emblematics: the representations of the body and the experiential aspects of the body with injury. According to Jodelet (1984), studies on social representations of the body end up demonstrating two approaches: one is psychological, of a more individual and subjective level, which demonstrates the relationships of the person with their own body, sensations of pleasure or pain, everyday life, body practices, and their body image; and the other is collective, which refers to the dynamics of the social context, including the social representations that emerge from the media through social roles and belonging to social categories such as gender, class, disability, and which ultimately influence the subjective knowledge of the body.

In reference to the psychological aspects and experiential aspects of the body with injury, the “My body alone” Class emerged which brought elements of the first instances of contact with the body, featuring the presence of hospitalization, pain, and relationships with health care professionals. At that moment, the body as an individual object is the focus and the concepts of the Medical Model of Disability are presented as central. The speech evoked by the participants corroborated the study by Moreno-Fergusson and Amaya Rey (2012) where body changes are difficult to confront for people with acquired physical disabilities; but over time, they acquire knowledge about their body and rebuild a new corporeality, new abilities, and a new vision about themselves.

A fact exhibited by some participants of this study and also seen by Moreno-Fergusson and Amaya Rey (2012) is the alteration in the perception of time. The new body shape often hinders the performance of daily activities with the same agility as other people or as they did before the injury.

It was observed that the greater degree of the injury the more the participants were bothered by dependence and the need to ask for help. One of the objectives of body rehabilitation is precisely that people with disabilities acquire greater autonomy in their daily activities. In view of this, it is necessary to say that the Social Model of Disability questions the conception of disability as an exclusively organic aspect, but understands that injury is the object of medical care (Mello & Nuernberg, 2012), thus fitting the analysis about the characteristics of the environment and the social arrangement that create barriers to access medical care. In this sense, within the context of medical body care, a look at the Social Model of Disability must consider the social determinants of health (Nogueira et al., 2016) so that it is possible to achieve health promotion in the condition of disability.

When talking about their body experiences, participants with spinal cord injuries cited the neurogenic bladder as a crucial and impeding factor in their routines. This was also found in the Moreno-Fergusson and Amaya Rey (2012) study which shows that the management of excretion functions has a direct impact on daily life, altering their intimacy, privacy, and individuality. In a study by Abbot, Jepson, and Hastie (2015) of English men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the expectations and norms related to gender roles directly conflict with the body with disability and the need for care, reducing the notion of intimacy and individuality that for them would be conditions allowed for people without disabilities.

Frequently cited in the interviews, the rehabilitation environment, the relationship with professionals, and the relationship with other people with disabilities emerged as contexts for the exchange of experiences that enhance the feeling of belonging, helping in the appropriation of physical condition (Vasco & Franco, 2017). On the other hand, it is necessary to emphasize that in the context of care, the establishment of social interactions in which the person with the disability receives infantilized treatment is frequent, with excessive protection or even with a focus on dependence. Thus, this hinders the coping and resignificance process of the body and the physical condition.

However, body rehabilitation alone does not provide quality of life: Another aspect evidenced in the statements related to the body experiences of the participants is how the physical environment that surrounds them interacts with the new corporeality. These statements generated Class 1, entitled “My body in the world”, a class that articulates the concepts of accessibility. The normalization of spaces for a standard body deprives people with disabilities of their rights as citizens (Ayres, Nuernberg, & Rial, 2016). The dissatisfaction of the participants sustains itself as a human rights issue; Diniz et al. (2009) report that the guarantee of equality between people with or without body injury goes beyond the provision of biomedical services since bodily impairments gain meaning from experiences of social interaction.

The contents that showed aspects of social representations in the interviews were divided into three themes: the social representations of the body without disability; social representations of the body with disability from the point of view of the people with the physical disabilities themselves; and finally, how people with physical disabilities believe that people without disabilities represent the injured body. Aspects of the social representations of the body generated Class 5 entitled “What I think of the body” which featured content representative of a standard, non-disabled body.

The contents sometimes navigated from aesthetics and beauty to health and their care; sometimes associating beautiful with healthy. This corroborates with the studies by Justo,Camargo, and Alves (2014) and Justo and Camargo (2013) in which it was shown that body care is related to both beauty and health. These two objects stand out as structural elements in the studies on social representations of the body, presenting an important zone of intersection. In this sense, it is reflected in the construction of social norms and stereotypes linked to physical beauty and the healthy body that is based on the usability of the body as a practical object in a material and social environment built for bodies without disabilities. This scenario reinforces the relevance and the need for public policies to be based on the Social Model of Disability.

It was observed in the speech of the interviewees that sometimes when they mentioned concern for aesthetics, they referred to the social context and to third parties, whereas in the individual context the speech is focused on health. Reinforcing the findings of Justo et al. (2014) which state that in the context of health the body is seen as individual. In the context of beauty, representation is supported in the subject-world relationship, which attributes to it an external weight due to social norms. Thus, the social representations of the body for people with acquired physical disabilities are objectified in a similar way to the findings of studies of people without disabilities.

As mentioned previously, the social representations of the body are structured around the aspects of health and aesthetics, however, particularities appear in other classes that concern the specific care of the injured body as well as elements of functionality and movement. Wagner (1994) proposed two levels in the evaluation of social representations: the individual and the social. The individual level refers to the beliefs and perceptions of the subjective domain and reveals social representations of a certain social category - as presented in the “What I think of me” Class. The social level represents the characteristic beliefs of culture and society, represented by the Class “What they think of me”. According to Martins (2015), the social body modifies the way the physical body is perceived, and the body’s own physical experience is supported by a vision of society.

It is observed that in the interviews the participants’ perception of themselves and their bodies corresponded to normality, but with a different way of achieving life goals, especially due to the limitations and challenges they cope in the presence of obstacles. The representations of the disabled body were supported in the social representations of the body. It should be noted that the word “normal” when referring to the body itself was enunciated several times. The change in habits appears to be a more impacting factor than bodily change. Social representations as phenomena present in the social thinking are closely related to the concrete context of practices, in a process of mutual influence (Camargo & Bousfield, 2014) which demonstrates the importance of guaranteeing the material conditions that allow social participation and the exercise of autonomy to influence the dynamic processes of formation of socially shared thinking.

Although the limitations have been evidenced, positive contents related to the experiences have also appeared, with a focus on potentialities and personal development. For many, there has been a transformation in the meaning of living: following the example of the findings of Vasco and Franco (2017) which indicate that no matter how difficult the experience of disability is, one does not necessarily attribute a bad meaning to life.

According to Barsaglini and Biato (2015), the changes in the perception of the injured body are not linear, the sentiments are mobilized as the situations experienced denounce the difference, especially in heterogeneous relationships with non-disabled people. Class 2 deals precisely with heterogeneous relationships, and for this reason, it was named, “What you think of me”. The representative aspects of the Class are focused on the external view, stigmas, and prejudices; the stereotype of disability appears as a central element.

The social representations of the disability that emerge from this class have negative connotations, because they refer to a disease, weakness, incapacity, and pity, and concern the attitudinal barriers these people face. According to Amaral (2002), the attitudinal barriers are the prejudices, stereotypes, and stigmas directed at disability that underpin their social segregation. The stigma of the injured body constitutes the condition of a person with disability (Mello & Nuernberg, 2012). No matter how much one tries to describe embarrassing situations experienced by attitudinal barriers, Fernandes and Denari (2017) maintain that people without disabilities will never know the extent of moral damage that the experience entails.

Morgado et al. (2017) have demonstrated a gap in the social representations of disability between people with and without disabilities; people without disabilities were more imbued with stigma and presented lesson reflection on the subject. The discourse emitted seemed to be ready and was based on the conceptions of the medical model and pathologist of disability. This is found in accordance with the data obtained in this study, where it was observed that the social representations of the body with disability in heterogeneous relationships are supported by the very social representations of disability, which is in turned based on biomedical models propagated by health professionals and the media. In this sense, the propagation of pro-inclusive information by the media would contribute to the deconstruction of the attitudinal barriers.

The stereotypes associated with people with disabilities consider them unattractive and asexual, affecting the life plans of individuals of both genders, but mainly women (Gesser et al., 2013). This fact was elucidated in this study according to the contents about loving and sexual experiences after injury with non-disabled partners. Men and women showed differences in this regard, while the former did not show significant differences in how they related lovingly, women had difficulties in creating new relationships since they did not correspond to the male standards sought in relation to sexuality. Thus, having the body as the principal mediating element, centered on physical beauty and health, expectations, and life plans regarding sexuality are similar between people with and without disabilities. However, the barriers to the effective experience of sexuality are more significant to those who have some disability (Carvalho, 2020).

Corroborating with the findings of Gesser and Neurenberg (2014) which showed that the view of people with disabilities as asexual may be attributed to the infantilization of this social category. According to the authors, one of the aspects that hinders people with disabilities to relate sexually is the stigma that people with disabilities are sterile, they have children with disabilities, or they cannot care for them. Carvalho (2020) states that the development of sexuality of people with disabilities is hindered by physical and attitudinal barriers and that the stereotype referring to the asexuality of people with disabilities can be evidenced through family overprotection, which assumes an infantilizing posture, and through the absence of sexual education in educational and social contexts.

The context of infantilization is mainly seen with regard to women, since characteristics socially linked to femininity, such as being gentle, fragile, docile, and dependent, are enhanced when disability and gender intersect. This is especially true when referring to aspects of sexuality, with the media as a reinforcement of the stigma (Gesser et al., 2013; Luiz & Nuernberg, 2018). Moreover, the view that disabled women occupy a position of lesser qualification and reduced social and political participation, a view already historically linked to unequal gender relations with or without disabilities, makes it even more difficult to access resources that contribute to autonomy and to developing life planning such as work, culture, leisure, sexuality, and the experience of motherhood (Nicolau, Schraiber, & Ayres, 2013).

According to Gesser and Nuernberg (2014), denying the sexuality of a person with disability is a disconsideration of their human condition and rights. Still, the lack of information and the unpreparedness of health professionals are factors that hinder the rendering of services. In order for people with disabilities to be the subject of rights, it is essential that public policies take into account the issue of sexuality, so that their condition as ordinary people is recognized along with their sexual and reproductive rights (Mell & Nuernberg, 2012).

Jones et al. (2015), when interviewing women with congenital physical disabilities, showed that the body with disability is considered an illegitimate body, and that delegitimization seems to be more associated with functional aspects of the body than aesthetics. Agmon, Sa’ar, and Araten-Bergman (2016) report that the body with disability has representations that bring a reduced social position, such as representations of dependence, infantilization, asexuality, and stigmas about cognitive ability, which affects the self-confidence of the participants of the study even if they were aware that they were underestimated and excluded. In this study, it was shown that social representations of the body for people with physical disabilities illustrate the aspects of health and beauty as structural axes. By associating it with other representational elements, such as disability, the body becomes evident as a social object since the body with disability becomes a problem when interacting with a world unprepared to deal with its differences. However, it is noticeable that the representation of the body with injuries is not completely distanced from the social representations of the standard body, but it is supported in this conception.

Final Considerations

This study aimed to characterize the social representations of the body for people with acquired physical disabilities. The results demonstrate social representations of the body with a similar approach to the findings from studies with non-disabled people. The perspective of the body contours health and/or aesthetics, when referencing the body with disability, even if it is still supported in the social representations of the body. The participants brought new elements related to its context as the routine of bodily care and functionality, and presented the limitations and obstacles encountered. No significant differences were found in the social representations of men and women, but certain experiential elements were distinguished, evidencing sustained behavior related to gender roles. It is worth noting that the different contexts in which the participants were inserted influence the way they see and experience their corporeality.

The results found are expected to contribute to new studies of social representations on the subject. In view of the worsening of Brazilian socio-economic conditions, the increase in the aging population, and chronic disease conditions, a significant increase in the prevalence of people with disabilities is expected within the coming decades. This makes it even more evident to expand studies in an interdisciplinary manner, to guarantee access to medical services as a basic right, and above all, to institute policies that consider the social rights of people with disabilities.

Aiming to contribute to the development of new research on this phenomenon, limitations experienced in this study are described: The socio-economic condition was not controlled. However, the difference regarding the perception of disability according to the socio-economic level was noted since this directly impacts the relationship with the social environment and the condition of equal rights. New studies are indicted to include a larger number of participants controlling the socio-economic variable. Furthermore, the issue of gender has gained a greater focus in Brazilian society and represents a nucleus of tension and discrimination. In this sense, it is inferred that it affects people with disabilities more significantly owing to the stereotypes and constructed social roles, proving to be a relevant theme for further study. In addition, the limited number of studies on social representations of the body in the context of disability hinders further discussion of the results.

Disability presents itself as an inherent condition of human life; it can be temporary or permanent, from birth or acquired. However, there is a need for more studies so that the body and the disability can be understood in a multidisciplinary way; above all, research is indicated using the Social Representations Theory since it directly contributes to the understanding of the phenomenon.

Moreover, due to its constant presence in the individual or social context, the importance of inserting disability as a category of transversal analysis to the research is emphasized as categories such as sex, income, age group, for example, are already established. Finally, it is pertinent to create public spaces that pay attention to body diversity and stimulate the social participation of people with physical disabilities, as well as to create public health and assistance policies that consider their possibilities while also citizens with rights.

REFERENCES

Abbot, D., Jepson, M., & Hastie, J. (2015). Men living with long-term conditions: exploring gender and improving social care. Health and Social Care in the Community, 24(4), 420-427. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12222 [ Links ]

Agmon, M., Sa’ar, A., & Araten-Bergman, T. (2016). The person in the disabled body: a perspective on culture and personhood from the margins. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15, 147. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0437-2 [ Links ]

Amaral, L. A. (2002). Diferenças, estigma e preconceito: o desafio da inclusão. Em: M. K. de Oliveira. Psicologia, educação e temáticas da vida contemporânea. São Paulo: Moderna. [ Links ]

Andrieu, B. (2006). Corps. Em: B. Andrieu (Org.), Le dictionnaire du corps en sciences humaines e sociales (pp. 103-104). Paris: CNRS Editions. [ Links ]

Arruda, A. (2015). Image, social imaginary and social representation. Em: G. Sammut, E. Andreouli, G. Gaskell, & J. Valsiner. The Cambridge handbook of social representations (pp. 128-142). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ayres, M. de la B., Nuernberg, A. H., & Rial, C. S. (2016). Mídia e deficiência: uma abordagem interdisciplinar. R. Inter. Interdisc. INTERthesis, 13(3), 61-80. [ Links ]

Barnes, C., & Mercer, G. (2001). Disability culture: assimilation or inclusion. Em: G. L. Albrecht, K. D. Seelman, & M. Bury, Handbook of Disability Studies (pp. 515-534). Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Barsaglini, R. A., & Biato, E. C. L. (2015). Compaixão, piedade e deficiência física: o valor da diferença nas relações heterogêneas. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, 22(3), 781-796. doi: 10.1590/S0104-59702015000300007 [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., & Bousfield, A. B. S. (2014). Em direção a um modelo explicativo da relação entre representações sociais e práticas relativas a saúde: a ideia de adesão representacional. Em: E. M. Q. O. Chamon; P. A. Guareschi; P. H. F, Campos. Textos e debates em representações sociais, (pp. 261-284). Porto Alegre: ABRAPSO. [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., Goetz, E. R., Bousfield, A. B. S., & Justo, A. M. (2011). Representações sociais do corpo: estética e saúde. Temas em Psicologia (Ribeirão Preto), 19, 257-268. [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., & Justo, A. M. (2013). IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, 21(2), 513-518. [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., Justo, A. M., & Aguiar, A. (2008). Corpo real, corpo ideal: a autoimagem definindo práticas corporais. In: Trabalhos Completos do VI Congresso Iberoamericano de Psicologia, Lima, Peru. [ Links ]

Carvalho, A. N. (2020). Representações sociais sobre a sexualidade das pessoas com deficiência: um estudo com universitários com e sem deficiência física. Dissertação de Mestrado. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, . Recuperado de: https://ri.ufs.br/bitstream/riufs/10968/2/ALANA_NAGAI_LINS_CARVALHO.pdf [ Links ]

Castilho, S. M. (2001). A Imagem Corporal. Santo André: Ed. ESETec. [ Links ]

Decreto Legislativo n. 186., de 09 de julho de 2008. (2008). Aprova o texto da Convenção sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência e de seu Protocolo Facultativo, assinados em Nova Iorque, em 30 de março de 2007. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República. Acesso em 15 de outubro, 2016, em Acesso em 15 de outubro, 2016, em http://www2.senado.gov.br/bdsf/item/id/99423 . [ Links ]

Diniz, D., Barbosa, L., & Santos, W. R. dos. (2009). Deficiência, direitos humanos e justiça. Sur. Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos, 6(11), 64-77. doi: 10.1590/S1806-64452009000200004 [ Links ]

Fernandes, A. P. C. dos S., & Denari, F. E. (2017). Pessoa com deficiência: estigma e identidade. Revista da FAEEBA. Educação e Contemporaneidade, 26(50), 77-89. [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2009). Introdução à pesquisa qualitativa (3a ed.). São Paulo: Artmed. [ Links ]

Furtado, E. R. G. (2009). Representações sociais do corpo, mídia e atitudes. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil. [ Links ]

Gesser, M., & Nuernberg, A. H. (2014). Psicologia, Sexualidade e Deficiência: Novas Perspectivas em Direitos Humanos. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 34(4), 850-863. doi: 10.1590/1982-370000552013 [ Links ]

Gesser, M., Nuernberg, A. H., & Filgueiras-Toneli, M. J. (2013). Becoming a person in the gender and disability intersection: a research report. Psicologia em Estudo, 18(3), 419-429. doi: 10.1590/S1413-73722013000300004 [ Links ]

Ghiglione, R., & Matalon, B. (1993). O Inquérito - Teoria e Prática. Oeiras: Celta Editora. [ Links ]

Gil, A. C. (2008). Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social (6ª ed.). São Paulo: Atlas. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2011). Censo Demográfico: Resultados Preliminares da Amostra. Acesso em 15 de setembro, 2016, em Acesso em 15 de setembro, 2016, em http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/resultados_preliminares_ amostra/default_resultados_preliminares_amostra.shtm [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1984). The representation of the body and its transformations. Em: R. Farr & S. Moscovici (Orgs.), Social representations (pp. 211-238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1986). La representación social: Fenómenos, concepto y teoría. Em S. Moscovici (Org.), Psicología social (pp. 469-494). Barcelona/Buenos Aires/México: Paidós. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1994). Le corps, la persone et autrui. Em: S. Moscovici (Org.), Psychologie sociale dês relations à autrui (pp. 41-68). Paris: Nathan. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (2017). Representações sociais e mundos de vida. Curitiba: PUCPRess. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D., Ohana, J., Bessis-Moñino, C., & Dannenmuller, E. (1982). Systeme de representation du corps et groupes sociaux (relatório vol. 1). Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale: E.H.E.S.S. [ Links ]

Jones , B.S., Duarte , B.T., Astorga , U.N., Pardo , M.M., & Sepúlveda , P. R. (2015). Aproximación a la experiencia de cuerpo y sexualidad de un grupo de mujeres chilenas con discapacidad fisica congenita. Revista Chilena de Terapia Ocupacional, 15(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-5346.2015.37127 [ Links ]

Justo, A. M., & Camargo, B. V. (2013). Cuerpo y cognición social. Liberabit: Revista de Psicología, 19(1), 21-32. [ Links ]

Justo, A. M., Camargo, B. V., & Alves, C. D. B. (2014). Os efeitos de contexto nas representações sociais sobre o corpo. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 30(3), 287-297. [ Links ]

Justo, A. M., Camargo, B. V., & Bousfield, A. B. (2020). Obesidade, representações e categorização social. Barbarói, 56, 164-188. doi: 10.17058/barbaroi.v0i0.14752 [ Links ]

Luiz, K. G., & Nuernberg, A. H. (2018). A sexualidade da pessoa com deficiência nas capas da Revista Sentidos: inclusão ou perpetuação do estigma? Fractal, Rev. Psicol ., 30(1),58-65. [ Links ]

Martins, B. S. (2015). Uma reinvenção da deficiência: novas metáforas na natureza dos corpos. Fractal: Revista de Psicologia, 27(3), 264-271. doi: 10.1590/1984-0292/1653 [ Links ]

Mello, A. G. de, Nuernberg, A. H., & Block, P. (2014). Não é o corpo que nos discapacita, mas sim a sociedade: a interdisciplinaridade e o surgimento dos estudos sobre deficiência no Brasil e no mundo. Em: E. Schimanski & F. G. Cavalcante (Orgs.), Pesquisa e extensão: experiências e perspectivas interdisciplinares (pp. 91-118). Ponta Grossa: Editora UEPG. [ Links ]

Mello, A. G. de, & Nuernberg, A. H. (2012). Gênero e deficiência: interseções e perspectivas. Revista Estudos Feministas, 20(3), 635-655. [ Links ]

Meurer, B., & Gesser, M. (2008). O corpo como lócus de poder: articulações sobre gênero e obesidade na contemporaneidade. In Fazendo Gênero 8: Corpo, Violência e Poder, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil. [ Links ]

Moreno-Fergusson, M. E., & Amaya Rey, M. C. del P. (2012). Cuerpo y corporalidad en la paraplejia: significado de los cambios. Avances en Enfermería, 30(1), 82-94. [ Links ]

Morgado, F. F. da R., Castro, M. R. de, Ferreira, M. E. C., Oliveira, A. J. de, Pereira, J. G., & Santos, J. H. dos. (2017). Representações Sociais sobre a Deficiência: Perspectivas de Alunos de Educação Física Escolar. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 23(2), 245-260. doi: 10.1590/s1413-65382317000200007 [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (2012). A psicanálise, sua imagem e seu público. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes (Original publicado em 1961). [ Links ]

Nicolau, S. M., Schraiber, L. B., & Ayres, J. R. C. M. (2013). Mulheres com deficiência e sua dupla vulnerabilidade: contribuições para a construção da integralidade em saúde. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 18(3), 863-872. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232013000300032 [ Links ]

Nogueira, G. C., Schoeller, S. D., Ramos, F. R. S., Padilha, M. I., Brehmer, L. C. F., & Marques, A. M. F. B. (2016). Perfil das pessoas com deficiência física e políticas públicas: a distância entre intenções e gestos. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, 21(10), 3131-3142. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320152110.17622016 [ Links ]

Sampieri, R. H., Collado, C. F., & Lucio, P. B. (2013). Metodologia de Pesquisa. São Paulo: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Vasco, C. C., & Franco, M. H. P. (2017). Indivíduos Paraplégicos e Significado Construído para o Lesão Medular em suas Vidas. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 37(1), 119-131. doi: 10.1590/1982-3703000072016 [ Links ]

Veloz, M. C. T., Nascimento-Schulze, C. M., & Camargo, B. V. (1999). Representações sociais do envelhecimento. Psicologia Reflexão e Crítica, 12(2), 470-50. [ Links ]

Wagner, W. (1998). Sócio-gênese e características das representações sociais. Em: A. S. P. Moreira & D. C. de Oliveira. (Orgs.), Estudos interdisciplinares de representação social (pp. 3-25). Goiânia: AB. [ Links ]

Yin, R. (2001). Estudo de caso: planejamento e método. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. B.B. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; .A.B.S.B.in a,c,d,e; J.P.S. in c,d,e; A.I.G. in c,d,e.

How to cite: Berri, B., Bousfield, A.B.S., Silva J.P., & Giacomozzi A.I. (2020). Social representations of the body for people with physical disabilities. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2322. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2322

Correspondence: Bruna Berri, e-mail: brunaberri@hotmail.com. Andréa Barbará da Silva Bousfield, e-mail: andreabs@gmail.com. Jean Paulo da Silva, e-mail: jeanps.silva@gmail.com. Andréia Isabel Giacomozzi , e-mial: agiacomozzi@hotmail.com. Laboratório de Psicologia Social da Comunicação e Cognição, UFSC - CFH Departamento de Psicologia - Campus Universitário Trindade. Bloco E - 5º andar CEP:88.040-900 - Florianópolis - SC

Received: June 10, 2019; Accepted: September 18, 2020

texto en

texto en