Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 16-Set-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2321

Original articles

Alliance Rupture: an unsuccessful case of psychoanalytic psychotherapy with a borderline patient

1Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos. Brasil

This paper aims to understand the processes of rupture of the Therapeutic Alliance (TA) of a case of interrupted psychoanalytic psychotherapy (PP) with a patient with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). This is a systematic case study that comprises 15 sessions of PP, one patient with complaints of impulsiveness and difficulties in interpersonal relationships, and his female therapist. The sessions were videotaped and transcribed. The identification of ruptures was made by the Rupture Resolution Rating System (3R's). There were 100 ruptures of AT, of these 69% were withdrawal ruptures and 31% of confrontation. We found 30 contributions from therapist to ruptures. The withdrawal ruptures are more subtle and difficult to identify, occurring more frequently than those of confrontation in the treatment. In the case of patients with BPD, therapists should develop skills to make interventions focused on TA. The need for other studies that seek to replicate the research in other cases of success and therapeutic failure is highlighted.

Keywords: ruptures; therapeutic alliance; psychotherapy; process research; borderline personality disorder

Esse trabalho tem como objetivo compreender os processos de ruptura da Aliança Terapêutica (AT) de um caso de psicoterapia psicanalítica (PP) interrompida, realizada com paciente com Transtorno de Personalidade Borderline (TPB). Trata-se de estudo de caso sistemático, que contempla 15 sessões de PP, com um paciente com queixas impulsividade e dificuldades de relacionamento e sua terapeuta. As sessões foram gravadas em vídeo e transcritas. A identificação das rupturas na AT foi feita pelo Rupture Resolution Rating System. Foram encontradas 100 rupturas da AT, destas 69% são rupturas de evitação e 31% de confrontação. Foram verificadas 30 contribuições da terapeuta para as rupturas acontecerem. As rupturas de evitação são mais sutis e de difícil identificação, apresentando-se em maior frequência do que as de confrontação. Diante de pacientes com TPB, os terapeutas devem desenvolver habilidades para fazer intervenções com foco sobre a AT. Destaca-se a necessidade de outros estudos que busquem replicar a pesquisa em outros casos, de sucesso e insucesso terapêutico.

Palavras-chave: rupturas; aliança terapêutica; psicoterapia; investigação de processos; transtorno de personalidade borderline

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo comprender los procesos de ruptura de la Alianza Terapéutica (AT) de un caso de psicoterapia psicoanalítica (PP) interrumpida realizada con un paciente con Trastorno de Personalidad Borderline (TPB). Se trata de un estudio de caso sistemático, el caso contempla 15 sesiones de PP, un paciente con quejas de impulsividad y dificultades de relación y su terapeuta. Las sesiones fueron grabadas en vídeo y transcritas. La identificación de las rupturas en la AT fue hecha por el Rupture Resolution Rating System. Se encontraron 100 rupturas de la AT, de estas 69% son rupturas de evitación y 31% de confrontación. Han sido verificadas 30 contribuciones del terapeuta para las rupturas. Las rupturas de evitación son más sutiles y de difícil identificación, presentándose en mayor frecuencia que las de confrontación en el tratamiento. Ante los pacientes con TPB los terapeutas deben desarrollar habilidades para hacer intervenciones con foco sobre la AT. Se destaca la necesidad de otros estudios que busquen replicar la investigación en otros casos de éxito y fracaso terapéutico.

Palabras clave: rupturas; alianza terapéutica; psicoterapia; investigación de procesos; Trastorno de Personalidad Limítrofe

Introduction

Early psychotherapy dropout is a significant phenomenon, frequently encountered by therapists in various theoretical approaches, with rates ranging from 15 to 75% (Arnow et al., 2007; Bados, Balaguer, & Saldanã, 2007). Among the factors associated with dropout, factors of the therapist-patient relationship stand out, especially the therapeutic alliance (TA). The meta-analysis by Sharf, Primavera and Diener (2010) revealed a relatively strong relationship between TA and dropout (d: 0.55), indicating that patients with weaker TAs are more likely to drop out of treatment early. The study of moderators suggests that the relationship between TA and dropout is stronger in individuals with less schooling, longer therapies and in the context of hospitalization. Establishing and maintaining a good alliance is, therefore, decisive to avoid treatment dropout and to create the conditions for therapeutic progress to occur (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, 2011; Krause, Altimir & Horvath, 2011).

The concept of the TA originates from the consideration of Freud (1913) on the need for the patient to connect positively with the therapist so that the analytical work can develop. The terms therapeutic alliance and working alliance were coined, respectively, by Zetzel and Greenson, who indicated their character of being conscious, non-conflicting and differentiated from transference (Gomes, 2015). However, the concept evolved and started to be conceived pantheorically, from the concept of Bordin (1979), as a relationship of conscious and purposeful mutual collaboration between patient and therapist in therapy, characterized by an agreement on aims, an assignment of tasks (agreed in the therapeutic contract) and the development of emotional ties. This pantheoric vision of the TA, with an emphasis on collaboration and consensus, influenced, although in a different and non-consensual way, most of the main current measures of the construct (Horvath et al., 2011; Krause et al., 2011).

The TA is currently recognized as a dynamic process that varies in intensity, frequency and duration, depending on the patient's diagnosis and the type of theoretical approach employed. These oscillations, called ruptures, can happen during treatment and even during the same session (Barros, Altimir & Pérez, 2016; Safran, Muran, & Eubanks, 2011). The ruptures are characterized by a deterioration in the TA, manifested by a lack of collaboration in tasks or objectives or a tension in the emotional bond and difficulty in negotiating aspects of the therapeutic relationship (Eubanks, Muran, & Safran, 2015; Safran & Muran, 2006; Safran, Muran, & Proskurov, 2009). The patient can avoid the therapeutic work and/or the therapist or confront them directly. These movements of rupture of TA are inevitable in any psychotherapy (Eubanks et al., 2015). However, when not repaired, ruptures can cause dropout from the treatment (Safran et al., 2011).

There is ample evidence that weakened alliances are correlated with the patient's unilateral termination of the therapy (Doran, 2016; Safran et al., 2009; Safran, Israel, & Einstein, 2006), while negative interactions (i.e., hostile and aggressive) between patient and therapist are associated with unfavorable outcomes (Coady, 1991; Samstag et al., 2008; Zilcha-Mano, Muran, Eubanks, Safran, & Winston, 2018). According to the meta-analysis of Safran et al. (2011), there is empirical evidence that individuals with personality disorders present greater intensity of ruptures at the start of therapy than those without personality disorders. Among the former, patients with Borderline Personality Disorders (BPD) present the highest rate of ruptures. This may explain the higher rates of treatment dropout among patients with this disorder (Kroger, Harbeck, Armbrust, & Kliem, 2013; Koons et al., 2001; Linehan et al., 2007; McMain et al., 2009).

Patients with BPD have inflexible and long-lasting patterns of emotional and interpersonal difficulties (Benjamin, 1993; Leichsenring, Leibing, Kruse, New, & Leweke, 2011a) that require from the therapist to manage central aspects of their pathology (Barnow et al., 2009; Kernberg, 2012; Lazarus, Cheavens, Festa, & Zachary Rosenthal, 2014; Skodol et al., 2002). For example, affective instability and lack of integration of the self and significant others is manifested through feelings of chronic emptiness, contradictory and impoverished perceptions of themselves and others, hindering the empathic experience and the relationship with the therapist. For this reason, it is recommended that interventions with these patients focus on the development and maintenance of the TA (Bennett, Parry, & Ryle, 2006; Geremia, Benetti, Esswein, & Bittencourt, 2016).

Because the alliance is so critical to the outcome, Safran and colleagues (Eubanks, Muran, & Safran, 2014; Muran et al., 2009; Safran & Muran, 1996, 2000; Safran et al., 2011; Safran et al., 2009; Safran et al., 2006; Safran, Muran, & Samstag, 1994) created and tested a model to resolve ruptures in the alliance during therapy. Recently, in order to systematize the codification of ruptures and resolutions of the TA, Eubanks et al. (2015) developed the Rupture Resolution Rating System (3R’s). The system aims to code ruptures in the TA and resolution interventions, in segments of psychotherapy sessions.

Gersh et al. (2017) conducted a study of 44 young people with BPD, aiming to explore the processes of rupture and resolution of the TA, through the 3RS. The study showed that ruptures occurred in 53% of the sessions and with the passage of treatment they tended to increase, with confrontations being more frequent. The ruptures that occurred at the beginning of treatment were associated with worse results. Conversely, greater resolution of the ruptures was associated with better results and could be opportunities for therapeutic growth.

Considering the relevance of the TA process for the adherence of patients with BPD to psychotherapy, this study aimed to identify the frequency and variations of the processes of rupture in the TA in an interrupted case of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, performed with a patient diagnosed with BPD. A further aim was to describe the characteristics of the overall therapeutic process.

Method

This was a systematic, idiographic, longitudinal and intensive case study. This type of study has similarities with traditional clinical case studies, however, it differs from these in that, among other aspects, it presents greater methodological rigor, such as the use of independent judges, analysis of recorded audio and video sessions and control over biases of the researcher (Edwards, 2007; Serralta, Nunes, & Eizirik, 2011).

The process under study and its participants

The analyzed case consists of a psychoanalytic psychotherapy process. The treatment was interrupted by the patient in the 15th session. The patient (fictionally named Carlos) was 30 years of age. His initial complaints were a lack of emotional control and difficulty in interpersonal relationships and with his partner. Carlos was seen in a private psychology practice. The therapist was female, 32 years of age and trained in psychoanalytic psychotherapy. The diagnosis of BPD was made by the therapist, based on her clinical experience and the application of the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure - SWAP-200 (Shedler & Westen, 1998; Westen & Shedler, 1999), a Q-sort type of instrument consisting of 200 statements that describe cognitive, affective and relational aspects of patients with personality problems. For the interpretation of the profile, standardized scores are used. T scores >60 are compatible with the categorical diagnosis of personality disorder, while T scores >55 indicate the presence of these traits. According to data obtained through the SWAP-200, Carlos presented characteristics compatible with the diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder, and histrionic characteristics. The most prominent pathological traits were emotional dysregulation and psychopathy. His psychological health index was indicative of a medium level of personality pathology.

Instruments

Process monitoring form. This form was prepared by the researcher to be completed by the therapist. It is a record of the scheduled sessions, the patient's frequency in the session, including any lateness, and noteworthy complications (such as, for example, failure in the recording equipment).

The Rupture Resolution Rating System (3RS) (Eubanks et al., 2015) is a system for observing ruptures in the TA during a psychotherapy session, with the aim of obtaining a classification of the type of rupture (withdrawal or confrontation), as well as the therapist's resolution strategies. This classification is made on a 5-point significance scale, from 1 (not significant) to 5 (highly significant). Subsequently, the rater assigns a classification of which rupture predominated in the session, based on frequency. The final assessment item refers to the extent to which the therapist caused or exacerbated the ruptures in the session. The system presents high inter-rater reliability (Eubanks, Lubitz, Muran, & Safran, 2018a). The Portuguese version of the 3RS manual was developed by the team.

The Psychotherapy Process Q-Set (PQS) (Jones, 2000) is a pantheoric Q-sort type instrument, which presents 100 items that describe the patient's attitudes and experiences, the therapist's actions and attitudes and the nature of the interaction between them. When observing a therapeutic session, the evaluator classifies the items on a 9-point scale, classifying the characteristics identified as the most prominent in the therapeutic process (positively salient) and those identified as the least characteristic (negatively salient). Items placed in the central categories are considered neutral or irrelevant. Forced distribution follows the normal curve and avoids the halocentric effect. Ordination is generally carried out by two or more trained judges. The Brazilian Portuguese version of the PQS was developed by Serralta et al. (2007) and presented semantic equivalence with the original instrument in English, and reliability coefficients between previously trained evaluators comparable to those obtained with the original instrument (Intraclass correlations greater than .70).

Procedures

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Vale do Rio dos Sinos (CAAE 39120214.6.0000.5344). The 15 psychotherapy sessions in this case were audio recorded and transcribed in full for later analysis using the 3RS. The quantification of the ruptures was performed considering five-minute segments in all sessions by pairs of judges. There were 6 judges: two Master’s students, a PhD student, a psychologist with a PhD in Clinical Psychology (all psychotherapists with psychoanalytic orientation), and two undergraduate students, without clinical experience. The judges received 20-hours of training, as instructed in the 3RS manual (Eubanks et al., 2015). In this study, the judges obtained a substantial degree of agreement (K= 0.760; z= 8.0001; p> .0001) in identifying the ruptures.

In order to identify the ruptures, during the playback of the video the judge must be attentive to the indicators of decreased collaboration between the patient and therapist and disagreements about the treatment objectives and tasks, taking into account the verbal and non-verbal aspects of the patient. The rupture codification process is complex and involves many steps and has been described in detail by Dotta (2019).

Analyses performed with the 3RS included the frequency of ruptures during the treatment and the frequency of the therapist's contribution to the ruptures. Subsequently, the mean occurrence of both withdrawal and confrontation ruptures was evaluated, the mean of the specific impact of the rupture subcategories on the TA, in each session, and the overall impact of the ruptures in the TA in all psychotherapy sessions.

For the analysis of the process with the PQS, each session was codified by pairs of previously trained judges, formed by different coders from those that evaluated the ruptures with the 3RS. The PQS evaluators were: 1 psychology PhD holder, 2 PhD students with clinical experience and 1 psychology undergraduate student, who was a Scientific Initiation scholarship holder, without clinical experience. The judges were blinded to the number of sessions, the result of the treatment and the other judges' assessments. The judges presented good reliability in the judgment of the sessions analyzed, with an intraclass correlation coefficient between .71 and .86. In order to obtain the result of the overall description of the therapeutic process, the mean of the 10 items of the PQS that were most and least characteristic of the process was calculated and ordered.

Results

Overall psychotherapy process

The therapy lasted 27 weeks. However, due to frequent absences between sessions, the patient attended only 15 of them. The patient was late for almost half of the sessions (46.7%). The mean duration of the 15 sessions was 34.25 minutes (SD= 11.30). Between the 1st and the 4th session, the mean duration was 29.25 minutes (SD= 6.07). Between the 5th and 11th sessions, the duration of psychotherapy increased, lasting for a mean of 41.87 minutes (SD= 8.98). The recording failed during session number 7 due to a lack of battery power in the camera.

The overall therapeutic process evaluated with the PQS showed that the therapy had few silences (item 12) and was permeated by significant material (item 88). The dyad discussed topics related to the patient's current life situation (item 69), as well as his aspirations (item 41), generally presenting a specific focus (item 23) on the discussion of the interpersonal (item 63) and loving relationships (item 64) of the patient. During the sessions, the patient felt safe and confident (item 44), was active (item 15) and initiated the subjects (item 25). He generally showed acceptance of the therapist's comments (item 42) and was able to understand the therapist's comments (item 5).

The therapist was self-confident (item 86) and communicated through a clear and coherent style (item 46). In her relationship with Carlos, she was responsive, involved (item 9) and showed tact (item 77). Her interventions were directed toward obtaining more information and elaboration (item 31) and to facilitating the patient's speech (item 3), giving attention to verbal aspects, without referring to non-verbal ones.

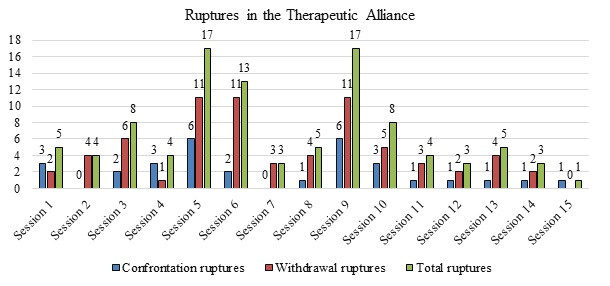

The identification of ruptures in figure 4 illustrates the number of rupture markers identified in each treatment session. Ruptures were identified in all the psychotherapy sessions. Over the 15 sessions, 100 rupture markers were found (a mean of 6.66 ruptures per session). Of these, 69% were withdrawal ruptures and 31% confrontation ruptures.

As shown in Figure 1, the sessions with the highest occurrence of ruptures were 5, 6 and 9 (with 17, 13 and 17 ruptures, respectively). The ones with the lowest occurrence were 7, 12 and 14 with 3 ruptures each, and session 15, with only one. A bimodal frequency distribution was observed, in which two main peaks of increase in ruptures were identified (sessions 5 and 9). Regarding the type of rupture, with the exception of the 1st, 4th and last sessions, there was a predominance of withdrawal ruptures in all sessions.

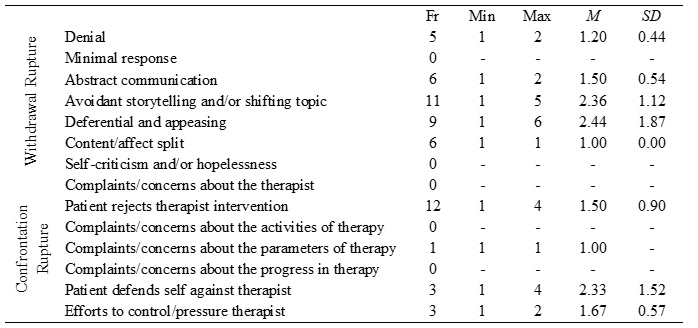

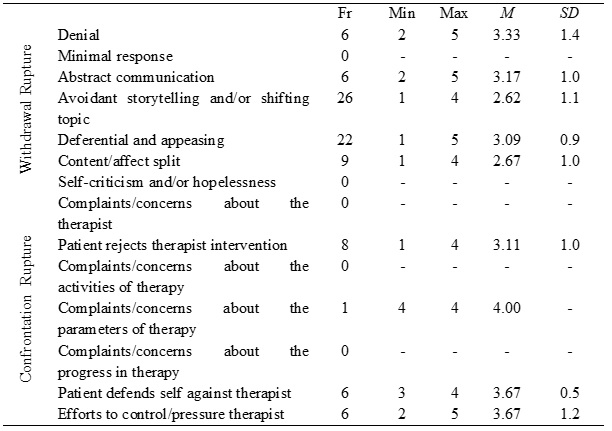

The withdrawal ruptures with a higher mean frequency throughout the treatment were: avoidant storytelling and/or shifting topic (Fr= 11), deferential and appeasing (Fr= 9), and abstract communication (Fr= 6). The predominant confrontation ruptures were: patient rejects therapist intervention (Fr= 12), defends self against therapist (Fr= 3) and efforts to control/pressure therapist (Fr= 3). The frequencies of the ruptures are presented in Table 1.

The intensity of the impact of the confrontation and withdrawal ruptures was examined. The intensity of the confrontation ruptures (M= 3.61; SD= 0.9) was slightly higher when compared to the impact of the withdrawal ruptures (M= 2.97; SD= 1.1). The most intense confrontation ruptures were: patient defends self against therapist (M= 3.67; SD= 0.5); efforts to control/pressure therapist (M= 3.67; SD= 1.12) and patient rejects therapist intervention (M= 3.11; SD= 1.0). The rupture of complaints/concerns about the parameters of therapy (M= 4.00) presented only one occurrence, and therefore, the 4 degree of impact refers only to this marker. Among the withdrawal ruptures, the markers with the greatest impact were denial (M= 3.33; SD= 1.4); abstract communication (M= 3.17; SD= 1.0) and deferential and appeasing (M= 3.09; SD=0.9). The other means of the impacts of the specific subcategories of the withdrawal and confrontation ruptures are presented in Table 2.

The ruptures (of confrontation and withdrawal) showed some mean significance for the TA (M= 3.0; SD= 0.62). In all sessions, the ruptures had at least some impact on the TA (score of at least 3.0). In sessions 5, 6, 9, 13 and 14 there were high impact ruptures (score 5.0). The sessions that had the greatest mean impact on the TA were 12 (M= 3.7; SD= 1.10), 13 (M= 4.2; SD= 1.10) and 14 (M= 4.0; SD= 1.10).

During the treatment, 30 contributions of the therapist to causing or exacerbating the ruptures were identified. The sessions in which the therapist most frequently contributed to the occurrence of ruptures were 5 (n= 10), 6 (n= 6), 8 and 9 (n= 5 in each), although this conduct was also observed in sessions 7, 10 and 11. In contrast, there were no contributions by the therapist to the ruptures in sessions 1, 2, 3, 4, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Discussion

Carlos' psychotherapy was understood as an unsuccessful therapy, as the patient unilaterally abandoned the treatment without the intended therapeutic gains having been achieved. The treatment lasted for 27 weeks. However, despite the weekly frequency contracted, it totaled only 15 sessions. Furthermore, the low number of sessions in relation to the treatment time was mainly due to the absences between sessions (there were 9 absences; of these, only one previously agreed with the therapist). The absences started in the 4th session, just when, according to the literature, it is expected that the TA starts to develop more effectively (Gersh et al., 2017).

When examining the sequence of attendance and absences in the sessions, it can be seen that, with the exception of the initial sessions, the process is practically all interspersed with absences. This possibly reflects the pair's difficulty in developing a sufficiently good TA at the beginning of the treatment (Horvath et al., 2011). As the patient spontaneously sought psychotherapy, expressing a need for help and apparently agreed with the initial contractual arrangements, there is a clear indication of disagreement over the therapy tasks (Bordin, 1979; Krause, Altimir & Horvath, 2011) that manifested itself in frequent absences and lateness.

Effective treatment models for BPD share, among other aspects, a focus on emotional experience, greater activity by the therapist and a focus on the therapeutic relationship (Weinberg, Ronningstam, Goldblatt, Schechter, & Maltsberger, 2011). The overall description of the process with the PQS does not capture any of these elements, although there are items in the instrument that describe these characteristics. Furthermore, this description shows an “apparent collaboration” in the exploration of significant material in the sessions, related to the problems that led the patient to treatment. There was also a significant lack of discussion of non-verbal behaviors that could have been due to resistance and difficulties in the interaction.

The fact that the overall analysis with the PQS takes into account the macroprocess in psychotherapy and focuses on the broad observation of how the patient and therapist experience the therapeutic process should be considered. Just like a photograph, a scene is captured as a whole and a panoramic view of the process is obtained, with a low degree of resolution (Bucci, 2007; Cordioli & Grevet, 2018). Therefore, in order to better understand the TA process, through the 3RS the aim was to address specific, detailed and immediate issues related to how the patient and therapist organized themselves during the psychotherapy session (the microprocess), observing the therapeutic scene with greater resolution to identify possible problems with the TA (Barcellos, Cardon, & Kieling, 2018; Bucci, 2007).

The evaluation of the TA throughout the treatment, analyzed at a microscopic level, identified problems in the collaboration between the patient and therapist in the present case, already verified at the macro level due to the absences and lateness mentioned. Ruptures were identified in all the sessions, a high number of ruptures (n=100), compared to other studies conducted using the 3RS with patients with BPD (Gersh et al., 2017). The ruptures were predominantly of avoidance, more frequent in the intermediate sessions (with the contribution of the therapist) and had some impact on the TA. Furthermore, it was observed that after the ruptures increased, in the intermediate sessions, there was a decrease in frequency. However, there was an increase in their impact on the TA in the sessions just before the end, in which the therapist contributed to the ruptures.

The difference between the frequencies of ruptures in the present study, when compared with some reports in the literature, is an interesting and unexpected finding. However, the pattern is consistent with the other indicators evidenced (absences and lateness). The fact that this was an interrupted (unsuccessful) psychotherapy with a BPD patient, supposedly more likely to demonstrate difficulties in establishing and maintaining the TA, cannot be disregarded (Boritz, Barnhart, Eubanks, & McMain, 2018; Safran et al., 2009). The study by Doran, Safran and Muran (2017), which examined the relationship between the therapeutic process and the negotiation of the TA in 47 patients with different clinical psychopathologies (anxiety and depression) and with personality disorders (48.9%), also highlighted fluctuation in the occurrence of ruptures (confrontation and withdrawal) over time.

Bennett et al. (2006) point out that a greater occurrence of ruptures of the TA and treatment dropout are common in patients with BPD. These patients have flaws in the process of representing the self and others (Caligor, Kernberg, & Clarkin, 2008) and under emotional activation, they tend toward concrete, non-mentalized thinking (Bateman, Campbell, Luyten, & Fonagy, 2018), showing impulsive behaviors related to flaws in emotional regulation, which lead to a rapid distortion of themselves and of the relationship with their therapists (Caligor et al., 2008; Leichsenring et al., 2011b). This distortion in the relationship with the therapist favors the occurrence and impact of ruptures in the TA (Spinhoven, Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck, Kooiman, & Arntz, 2007).

During the treatment, Carlos used withdrawal ruptures more frequently: avoidant storytelling and/or shifting topic, deference and appeasement and abstract communication. This finding suggests that the patient had difficulty expressing his dissatisfaction or anguish directly. According to the literature, the frequency of withdrawal ruptures is significantly higher in patients that dropout from treatment (Boritz et al., 2018). These ruptures, in comparison to those of confrontation, are more difficult to identify, since the behavior of the patient, in avoiding the therapeutic work or the therapist, is subtle, unclear or even obscured (Safran et al., 2011). Withdrawal ruptures may be disguised as superficial compliance or engagement, for example (Boritz et al., 2018).

Withdrawal behavior can therefore be seen as a strategy to regulate the intense and overwhelming emotion that is activated in the context of the therapeutic relationship (Bernecker, Levy, & Ellison, 2014). The study by Cash, Hardy, Kellett and Parry (2014) highlighted that the resolution of the rupture did not occur when therapists discussed or explored the ruptures directly, but when they approached the rupture indirectly by changing their approach to exploring issues that were more important to the patient. In the present study, however, rupture resolution strategies were not specifically analyzed. Nevertheless, the results suggest that in the absence of explicit clues for the withdrawal ruptures, the therapist may have positioned herself more passively when faced with them, having difficulty identifying and/or resolving them. The therapist's contributions to the occurrence of the ruptures suggest that she seemed to ignore the rupture markers and was not aware of what was happening at the relationship level, underestimating the impact these ruptures in the therapeutic collaboration had on the process. One study indicates that the therapist's contribution to ruptures is predictive of treatment dropout (Eubanks et al., 2018b). In addition, the literature highlights an apparent paradox in the work of resolving ruptures with BPD patients, as dealing with the rupture directly can be considered excessive and threatening for some individuals, although not addressing it directly can further exacerbate the rupture (Boritz et al., 2018).Despite the predominance of withdrawal ruptures, the confrontation ruptures also deserve attention. In these, the patient mostly rejected the therapist's interventions, defended himself from her and attempted to control the therapeutic process or the therapist. Confrontation ruptures occurred in 13 of the 15 treatment sessions. The judges also noted that, in rejecting the interventions of the therapist, the patient demonstrated a debauched tone, used sarcastic comments and described aggressive behaviors. A study by Gülüm, Soygüt and Safran, (2018) identified sarcastic humor as a third category of rupture. Sarcasm is a subtle form of aggressive communication, which expresses the difficulty in verbalizing feelings about the therapy or therapist, leading to treatment dropout in later sessions. In the final phase of psychotherapy, the decrease in ruptures is associated with their resolution (Eubanks et al., 2018b). In contrast, in the present case, the last sessions did not constitute a final phase, since in a supposedly long-term therapy the process would ideally have reached an intermediate stage (Luz, 2015). Therefore, the decrease in the occurrence of ruptures observed in the last sessions (sessions 12, 13 and 14), associated with the increase in their significance in terms of the impact on the TA, seems to indicate a deterioration in the TA that may have led to the patient’s dropout from the therapy.

It should be highlighted that the sessions in which the ruptures had the greatest impact on the TA were those that preceded the last session, when the patient talked about his decision to interrupt the treatment. These sessions were also the ones with the least ruptures, and in them there were no ruptures that showed expressions of self-criticism and/or hopelessness, complaints/concerns about the therapist, about the therapy activities or the treatment progress. It appears, therefore, that numerous minor ruptures may precede major ruptures. The hypothesis to be verified is that the non-resolution of less significant ruptures leads to an increase in the worsening of the TA, culminating in dropout. The ruptures can be comprehended as enactments,, a concept that highlights the role of the unconscious in the relationship between patient and therapist (Safran & Kraus, 2014; Safran & Muran, 2000). For Safran and Kraus (2014), ruptures in the TA are essentially unconscious movements between the pair. The therapist is involuntarily involved in the patient's functioning, thus re-enacting a form of dysfunctional relationship that is characteristic of the patient. These processes, when they do not become conscious and the targets of the therapeutic work, obstruct the development of a good therapeutic process. On the other hand, the therapist's awareness of the continuous fluctuations in the quality of the TA can present valuable opportunities to mobilize the process of change in the patient.

The initial or opening phase of treatment may be longer in therapy with patients with BPD, in view of the need to explore the ruptures that may interfere with the establishment and maintenance of the TA. Furthermore, the need to cultivate the TA with the main aim of the treatment becomes important, with the adaptation of psychotherapy to the patient's characteristics and constant monitoring of the fluctuations in the TA. The therapist's flexible and empathetic attitude is essential to deal with the ruptures, both those of withdrawal and confrontation.

The need to be cautious in the interpretation of the data presented is highlighted, in view of the limitations of this exploratory study. The coding of the ruptures in the TA was performed through the 3RS manual, which does not have categories for the assessment and codification of ruptures caused by the therapist. The evaluation of the microprocess measure involved only the patient's perspective. Although the judges received training and obtained substantial agreement, it is not known to what extent the coding is consistent with the coding of the gold standard 3RS.In the item “the therapist's contribution to the ruptures”, only the frequency at which the therapist exacerbated or contributed to them was identified. The assessment of the TA resolutions, which was not the target of this study, could better clarify the oscillatory behavior of the TA throughout treatment.

In future studies, it is suggested to include the coding of strategies that therapists can use to effectively identify and resolve TA ruptures. In addition, the ruptures and resolutions in the TA could be examined in multiple cases, with different psychopathologies and outcomes, with the performance of studies that assess the differences in the nature and predictive value of early and subsequent ruptures.

Conclusion

This study puts forward empirically supported hypotheses regarding the early dropout from therapy by a borderline patient. It reveals a process permeated by many ruptures from the beginning, which increased, first in number and then, in intensity, culminating in the session in which the patient communicated that he would dropout. The therapist contributed to the occurrence or increase in the ruptures. Her actions and interventions focused on the patient's problems, but not on the therapeutic relationship. Taken together, these factors seem to have been related to the dropout. However, considering the limitations of the purely descriptive design and the absence of specific analysis at the microprocessual level of the rupture resolution strategies, this hypothesis was not tested.

It should be emphasized that in Brazil, to date, there are no empirical assessments of ruptures in the TA. The 3RS system was recently translated into Brazilian Portuguese by the team of the Research Laboratory in Psychotherapy and Psychopathology (LAEPSI). Therefore, this is a pioneering study in the national context for the microprocessual examination of the TA, constituting an exploratory study that secondarily aims to introduce studies on the subject.

Nevertheless, the study presents contributions for the clinical practice by highlighting for discussion and analysis the role of the therapeutic relationship in the process of change and in the outcome of psychotherapy. Contemporary psychoanalytic theory emphasizes the mutual influence between therapist and patient and values the therapist's authenticity, flexibility and spontaneity. In this context, the TA acquires a central role, not only being a support for the initial stage of the treatment. With patients with personality disorders, such as borderline patients, who typically have difficulties in developing the alliance, the focus on this difficulty seems to be fundamental to the process. Working through ruptures in the alliance (that is, anticipating, identifying and resolving them) can provide patients with opportunities to learn to negotiate the tension between their own difficulties and the need for help versus the difficulties and needs of the therapeutic relationship, in a new and more constructive way.

Considering the empirical evidence indicating that the TA is a critical ingredient for change in various forms of therapy, it seems important to develop a well-articulated body of research with relevant knowledge about TA microprocessual measures. This study is the first developed in the country to use an approach based on external observers to microprocess the assessment of ruptures in the TA, and to explore how these processes unfold over time in therapy. Further studies should contribute to the expansion of this type of investigation in the country. National and international investigations of other individual cases, as well as multiple and comparative case studies on these microprocesses, developed with patients with different diagnoses, outcomes and therapeutic approaches may, in the future, shed more light on the complex issue of the contribution of the therapeutic relationship and alliance for adherence, dropout, success and/or failure of the psychotherapy.

REFERENCES

Arnow, B. A., Blasey, C., Manber, R., Constantino, M. J., Markowitz, J. C., Klein, D. N., … Rush, A. J. (2007). Dropouts versus completers among chronically depressed outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 97(1-3), 197-202. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.017 [ Links ]

Bados, A., Balaguer, G., & Saldaña, C. (2007). The Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and the Problem of Drop-Out. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(6), 585-592. doi: 10.1002/jclp [ Links ]

Bateman, A., Campbell, C., Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2018). A mentalization-based approach to common factors in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 44-49. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.005 [ Links ]

Barros, P., Altimir, C., & Pérez, J. C. (2016). Patients’ facial-affective regulation during episodes of rupture of the therapeutic alliance/Regulación afectivo-facial de pacientes durante episodios de ruptura de la alianza terapéutica. Estudios de Psicología, 37(2-3), 580-603. doi: 10.1080/02109395.2016.1204781 [ Links ]

Barcellos, M., Cardon, L., & Kieling, C. (2018). Evidências em Psicoterapia. Em A. Cordioli & E. H. Grevet (Eds.), Psicoterapia. Abordagens Atuais (4th ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Barnow, S., Stopsack, M., Grabe, H. J., Meinke, C., Spitzer, C., Kronmüller, K., & Sieswerda, S. (2009). Interpersonal evaluation bias in borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(5), 359-365. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.003 [ Links ]

Benjamin, L. (1993). Diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders: A structural approach. New York: G. Press, Ed. [ Links ]

Bennett, D., Parry, G., & Ryle, A. (2006). Resolving threats to the therapeutic alliance in cognitive analytic therapy of borderline personality disorder: A task analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 79(3), 395-418. doi: 10.1348/147608305X58355 [ Links ]

Bernecker, S. L., Levy, K. N., & Ellison, W. D. (2014). A meta-analysis of the relation between patient adult attachment style and the working alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 24(1), 12-24. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.809561 [ Links ]

Bordin, E.S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychoterapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16(3), 252-260. [ Links ]

Boritz, T., Barnhart, R., Eubanks, C. F., & McMain, S. (2018). Alliance Rupture and Resolution in Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 32(Supplement), 115-128. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2018.32.supp.115 [ Links ]

Bucci, W. (2007). Pesquisa sobre processo. Em E. Person, A. Cooper, & G. Gabbard (Eds.), Compêndio de Psicanálise (1st ed.), (pp. 320-336). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Caligor, E., Kernberg, O. F., & Clarkin, J. (2008). Psicoterapia dinâmicas das patologias leves da personalidade. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Cash, S. K., Hardy, G. E., Kellett, S., & Parry, G. (2014). Alliance ruptures and resolution during cognitive behaviour therapy with patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 24(2), 132-145. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.838652 [ Links ]

Coady, N. (1991). Therapist Interpersonal Processes and Outcomes in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Reasearch on Social Work Practice, 1(2), 122-138. [ Links ]

Cordioli, A. V., & Grevet, E. H. (2018). Psicoterapias: Abordagens Atuais (4th ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Doran, J. M. (2016). The working alliance: Where have we been, where are we going? Psychotherapy Research, 26(2), 146-163. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.954153 [ Links ]

Doran, J. M., Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2017). An Investigation of the Relationship Between the Alliance Negotiation Scale and Psychotherapy Process and Outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 449-465. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22340 [ Links ]

Dotta, P. (2019). Rupturas da Aliança Terapêutica: ilustração de um sistema de avaliação e análise de um caso de abandono em psicoterapia. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos - UNISINOS, Programa de Pós-graduação em Psicologia Clínica, Rio Grande do Sul, São Leopoldo, Brasil. [ Links ]

Edwards, D. J. (2007). Collaborative Versus Adversarial Stances in Scientific Discourse: Implications for the Role of Systematic Case Studies in the Development of Evidence-Based Practice in Psychotherapy. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 3(1), 6-34. doi: 10.14713/pcsp.v3i1.892 [ Links ]

Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2014). Alliance-focused training. Psychotherapy Theory Research Practice Training, 52(2), 169-173. doi: 10.1037/a0037596 [ Links ]

Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2015). Rupture Resolution Rating System (3RS): Manual. ResearchGate, (January), 1-16. doi: 10.13140/2.1.1666.8488 [ Links ]

Eubanks, C. F., Lubitz, J., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2018a). Rupture Resolution Rating System (3RS): Development and validation. Psychotherapy Research, (January), 1-16. doi: 10.13140/2.1.1666.8488 [ Links ]

Eubanks, C. F., Sinai, M., Israel, B., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2018b). Alliance Rupture Repair: A Meta-Analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 508-519. doi: 10.1037/pst0000185.supp [ Links ]

Geremia, L., Benetti, S. P. C., Esswein, G. C., & Bittencourt, A. A. (2016). A aliança terapêutica no paciente diagnosticado com transtorno de personalidade borderline. Perspectivas Em Psicologia, 20(2). doi: 10.14393/PPv20n2a2016-03 [ Links ]

Gersh, E., Hulbert, C. A., McKechnie, B., Ramadan, R., Worotniuk, T., & Chanen, A. M. (2017). Alliance rupture and repair processes and therapeutic change in youth with borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(1), 84-104. doi: 10.1111/papt.12097 [ Links ]

Gomes, F. G. (2015). Aliança terapêutica e a relação real com o terapeuta. Em S. EIZIRIK, Cláudio L.; Aguiar, Rogério W; Schestatsky (Ed.), Psicoterapia de orientação analítica: fundamentos teóricos e clínicos (3 ed.) (pp. 238-248). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Gülüm, İ. V, Soygüt, G., & Safran, J. D. (2018). A comparison of pre-dropout and temporary rupture sessions in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 28(5), 685-707. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1246765 [ Links ]

Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9-16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186 [ Links ]

Jones, E. E. (2000). Therapeutic Action: A guide to psychoanalytic therapy. New Jersey: Aronson. [ Links ]

Kernberg, O. (2012). The Inseparable Nature of Love and Aggression: Clinical and Theoretical Perspectives. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [ Links ]

Koons, C. K., Robins, C. J., Tweed, J. L., Lynch, T. R., Gonzalez, A. M., Mogs, J. Q., … Bastian, L. A. (2001). Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Women Veterans With Borderline Personality Disorder. Behavior Therapy, 32, 371-390. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5 [ Links ]

Krause, M., Altimir, C., & Horvath, A. (2011). Deconstructing the therapeutic alliance: Reflections on the underlying dimensions of the concept. Clinical and Health, 22(3), 267-283. doi: 10.5093/cl2011v22n3a7 [ Links ]

Kröger, C., Harbeck, S., Armbrust, M., & Kliem, S. (2013). Effectiveness, response, and dropout of dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder in an inpatient setting. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(8), 411-416. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.04.008 [ Links ]

Lazarus, S. A., Cheavens, J. S., Festa, F., & Zachary Rosenthal, M. (2014). Interpersonal functioning in borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of behavioral and laboratory-based assessments. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(3), 193-205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.007 [ Links ]

Leichsenring, F., Leibing, E., Kruse, J., New, A. S., & Leweke, F. (2011). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 377, 453-461. [ Links ]

Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A. M., Brown, M. Z., Gallop, R. J., Heard, H. L. & ... Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(7), 757-766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [ Links ]

Luz, A. B. (2015). Fases da Psicoterapia. Em C. L. Eizirik, R. W. de Aguiar, & S. S. Schestatsky (Eds.), Psicoterapia de orientação analítica: fundamentos teóricos e clínicos (pp. 249-266). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

McMain, S. F., Links, P. S., Gnam, W. H., Guimond, T., Cardish, R. J., Korman, L., & Streiner, D. L. (2009). A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(December), 1365-1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010039 [ Links ]

Muran, J. C., Safran, J., Gorman, B. S., Samstag, L. W., Eubanks, C.F., & Winston, A. (2009). The relationship of early alliance ruptures and their resolution to process and outcome in three time-limited psychotherapies for personality disorders. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(2), 233-248. doi: 10.1037/a0016085 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D., Israel, B., & Einstein, A. (2006). Has the concept of the therapeutic alliance outlived its usefulness?, 43(3), 286-291. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.286 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D., & Kraus, J. (2014). Alliance ruptures, impasses, and enactments: A relational perspective. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 381. doi: 10.1037/a0036815 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D, & Muran, J. C. (1996). The resolution of ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 447-458. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.447 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures: Diversity and integration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 233-243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200002)56:2<233::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-3 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D, & Muran, J. C. (2006). Has the concept of the therapeutic alliance outlived its usefulness? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(3), 286-291. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.286 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D, Muran, J. C., & Eubanks, C.F. (2011). Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 80-87. doi: 10.1037/a0022140 [ Links ]

Safran, J. D., Muran, J. C., & Proskurov, B. (2009). Alliance, negotiation, and rupture resolution. In Levy, R. A., Ablo, J. S., Gabbard, G. O. Handbook of evidence-based psychodynamic psychotherapy (pp. 201-225). Humana Press. [ Links ]

Safran, J. D, Muran, J. C., & Samstag, L. W. (1994). Resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures: A task analytic investigation. The Working Alliance: Theory, Research, and Practice, (July 2015), 225-255. [ Links ]

Samstag, L. W., Muran, J. C., Wachtel, P. L., Slade, A., Safran, J. D., & Winston, M. D. A. (2008). Evaluating Negative Process: A Comparison of Working Alliance, Interpersonal Behavior, and Narrative Coherency Among Three Psychotherapy Outcome Conditions. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 62(2), 165-194. [ Links ]

Sharf, J., Primavera, L. H., & Diener, M. J. (2010). Dropout and therapeutic alliance: A meta-analysis of adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(4), 637-645. doi: 10.1037/a0021175 [ Links ]

Serralta, F. B., Nunes, M. L. T., & Eizirik, C. L. (2007). Elaboração da versão em português do Psychotherapy Process Q-Set. Revista de Psiquiatria Do Rio Grande Do Sul, 29(1), 44-55. doi: 10.1590/S0101-81082007000100011 [ Links ]

Serralta, F. B., Nunes, M. L. T., & Eizirik, C. L. (2011). Considerações metodológicas sobre o estudo de caso na pesquisa em psicoterapia. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 28(4), 501-510. [ Links ]

Shedler, J., & Westen, D. (1998). Refining the Measurement of Axis II: A Q-Sort Procedure for Assessing Personality Pathology. Assessment, 5(4), 333-353. https://doi.org/10.1177/107319119800500403 [ Links ]

Skodol, A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Pfohl, B., Widiger, T. A., Livesley, W. J., & Siever, L. J. (2002). The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathology, comorbidity, and personaltity structure. Biological Psychiatry, 51(12), 936-950. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01324-0 [ Links ]

Spinhoven, P., Giesen-Bloo, J., van Dyck, R., Kooiman, K., & Arntz, A. (2007). The therapeutic alliance in schema-focused therapy and transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 104-115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.104 [ Links ]

Weinberg, I., Ronningstam, E., Goldblatt, M. J., Schechter, M., & Maltsberger, J. T. (2011). Common factors in empirically supported treatments of borderline personality disorder. Current psychiatry reports, 13(1), 60-68. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0167-x [ Links ]

Westen, D., & Shedler, J. (1999). Revising and Assessing Axis II, Part I: Developing a Clinically and Empirically Valid Assessment Method. American Journal of Psychiatry, (2), 258-272. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2014.06.029 [ Links ]

Zilcha-Mano, S., Muran, J. C., Eubanks, C. F., Safran, J. D., & Winston, A. (2018). When therapist estimations of the process of treatment can predict patients rating on outcome: The case of the working alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(4), 398-402. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000293 [ Links ]

Financing: This study was financed by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Universal call (nº 28/2008) and supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001

How to cite: Dotta, P., Feijó, L.P., & Serralta, F.B. (2020). Alliance Rupture: an unsuccessful case of psychoanalytic psychotherapy with a borderline patient. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2321. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2321

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. P.D.L. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; L.P.F. in b,c,d,e; F.B.S. in a,b,c,d,e.

Correspondence: Patricia Dotta; Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos. E-mail: patricia.dotta5@yahoo.com.br. Lan Paris Feijó; e-mail: lparisf@gmail.com. Fernanda Barcellos Serralta; e-mail: fernandaserralta@gmail.com

Received: June 10, 2019; Accepted: September 16, 2020

texto em

texto em