Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 15-Set-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2319

Original articles

New validity evidence for the Coping Strategies Inventory

1 Centro Universitário de Jaguariúna. Brasil

2 Universidade São Francisco. Brasil

The aim of the present study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Coping Strategy Inventory (CCI), through validity evidence based on the internal structure and relationship with other variables (character strengths). Participants were 927 college students, with an average age of 26 years (SD= 7.7) and most of them female. All responded to the Coping Strategies Inventory and the Character Strengths Scale (CSE). After analyzing the data, a new factorial organization with four factors, from the initial eight, is suggested. The factors are: Positive Reappraisal (α= .79), Distancing and Acceptance (α= .79), Social Support (α= .67) and Confrontation and Problem Solving (α= .86). The CCI scores correlated with the CSE scores, showing that the new factorial structure found presents validity evidence based on relationships with other variables. The results are discussed in the light of the literature.

Keywords: psychological assessment; coping; positive psychology; higher education; psychometric properties

O objetivo do presente estudo foi analisar as propriedades psicométricas do Inventário de Estratégias de Coping (IEC) por meio de evidências de validade baseadas na estrutura interna e na relação com outras variáveis (forças de caráter). Participaram 927 universitários, com idade média de 26 anos (DP= 7,7) e maioria do sexo feminino. Todos responderam ao Inventário de Estratégias de Coping e à Escala de Forças de Caráter (EFC). Após a análise dos dados, sugere-se uma nova organização fatorial com 4 fatores, dos 8 iniciais. Os fatores são: Reavaliação Positiva (α= 0,79), Afastamento e Aceitação (α= 0,79), Suporte Social (α= 0,67) e Confronto e Resolução de Problemas (α= 0,86). Os escores do IEC se correlacionaram com os escores da EFC, mostrando que a nova estrutura fatorial encontrada apresenta evidências de validade baseada nas relações com outras variáveis. Os resultados são discutidos à luz da literatura.

Palavras-chave: avaliação psicológica; enfrentamento; psicologia positiva; ensino superior; psicometria

El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar las propiedades psicométricas del Inventario de Estrategias de Afrontamiento (IEC) mediante las evidencias de validez basadas en la estructura interna y en la relación con otras variables (fortalezas de carácter). Participaron 927 estudiantes universitarios, con una edad media de 26 años (DE= 7.7), la mayoría eran mujeres. Todos respondieron al Inventario de Estrategias de Afrontamiento y la Escala de Fuerzas de Carácter (EFC). Después de analizar los datos, se sugiere una nueva organización factorial de cuatro factores, a partir de los ocho iniciales. Los factores son: Reevaluación positiva (α= .79), Retraimiento y aceptación (α= .79), Apoyo social (α= .67) y Confrontación y resolución de problemas (α= .86). Los puntajes del IEC se correlacionaron con los puntajes EFC, mostrando que la nueva estructura factorial encontrada presenta evidencias de validez basadas en relaciones con otras variables. Los resultados se discuten a la luz de la literatura.

Palabras-clave: evaluación psicológica; afrontamiento; psicología positiva; educación superior psicometría

Introduction

From a cognitive perspective, Lazarus and Folkman (1984a) defined coping as a set of efforts made to change the environment in an attempt to adapt in the best possible way to a stressful event, reducing or minimizing its aversive character. Changes can be cognitive or behavioral and are meant to help the individual manage situations that exceed their personal resources. For the authors, coping strategies can be learned and maintained or not throughout life, depending on the history of each individual, and can be problem-focused or emotion-focused.

For Folkman and Lazarus (1980), problem-focused coping comprises efforts to identify the problem, determine solutions and alternatives, assess the costs and benefits of actions, adopt attitudes to change what is possible and, if necessary, learn new skills related to the desired or expected result. When focusing on the problem, individuals seek to control the stressor and actions are aimed at reducing or eliminating it, which are considered to be more resolving strategies.

On the other hand, emotion-focused coping strategies are usually used in situations identified as unchangeable, being more palliative. In this type of strategy, the individual's emotion is modulated when facing a stressful situation, in an attempt to reduce the unpleasant sensation caused by stress. An example of that is a situation in which a person prays and feels better by doing so. However, it is important to remember that coping strategies are interrelated, as different people might analyze a stressful event differently. For one individual, the strategy used to solve the problem can turn to emotion, while for another it can focus on the problem, or both strategies can be used at the same time. A student can study to pass a test (problem) and also pray to be able to do well (emotion) (Folkman, & Lazarus, 1980).

Furthermore, the authors have developed and described a coping assessment model using these two forms (problem and emotion) and created the Ways of Coping Checklist (WCC), a clinical measure to assess coping. The WCC assesses stress coping strategies and experiences in a clinical context using 67 items, which can be responded as "yes" or "no". Subsequently, Folkman and Lazarus (1988) expanded their investigations about the instrument by reviewing data that were initially based on the literature. Through an empirical strategy, they proposed a new instrument, the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ). The main change was related to the form of the answers, which went from a checklist to a Likert scale. The WCQ consisted of 66 items from the Ways of Coping Checklist, encompassing thoughts, actions and strategies used by individuals to deal with internal and external demands of a specific stressful event, and ordinal responses with four possibilities. Individuals were expected to respond indicating the frequency in which they used each strategy, according to the following order, 0- not used; 1- used somewhat; 2- used quite a bit; 3- used a great deal. Items were selected in a qualitative way, and those considered redundant or unclear by the authors were removed or revised, and several items were changed at the suggestion of respondents (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988).

Based on the original study and some psychometric studies of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire, the instrument was subdivided into eight coping strategies: Confrontation, Distancing, Self-control, Social Support, Accepting Responsibility, Escape-Avoidance, Problem Solving, and Positive Reappraisal (Coyne, Aldwin, & Lazarus, 1981; Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, & Delongis, 1986; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). Internal consistency analysis for the eight factors proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (1988) indicated reliability coefficients between .61 (distancing) and .79 (positive reappraisal).

Other studies were conducted to look for validity evidence for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire.Vitaliano et al. (1985) found a five-factor solution with 42 items in the United States. Bramsen et al. (1995), in turn, found seven factors when adapting the Ways of Coping Questionnaire, to the Netherlands. In Norway, Falkum, Oiff and Aasland (1997) identified a six-factor structure, maintaining the 42 items of Vitaliano et al. (1985). More recently, Liew, Santoro, Edwards, Kang and Cronan (2016) adapted the instrument to the healthcare context, finding a four-factor structure for patients from the United States with fibromyalgia, while Corti et al. (2018) found a six-factor structure for Australian Parkinson's patients. These differences between the factor structures found are expected, as they are part of an adaptation of the instrument to different countries and cultures (Borsa & Seize, 2017).

Despite the different factor structures found, the Ways of Coping Questionnaire is considered one of the most widely used instruments to measure coping strategies (Hirsh et al., 2015; Pais-Ribeiro & Santos, 2001). In Brazil, the instrument was translated and adapted by Savóia, Santana and Mejias (1996). The latter authors, in their translation and adaptation study, named the instrument Inventário de Estratégias de Coping - IEC (Coping Strategies Inventory - CSI).

In Brazil, the CSI was translated and adapted from the original version with 66 items and eight factors developed by Folkman and Lazarus (1988). Savóia et al. (1996) verified the adequacy of the CSI translation into Brazilian Portuguese, as well as its validity evidence based on internal structure and relationship with other variables. First, the instrument was translated into Portuguese and analyzed by judges. Results indicated that, despite cultural and semantic issues, the translation remained true to the original in terms of question interpretation.

Regarding CSI's internal consistency with its own factors, all correlations were significant and ranged between r= .42 and r= .68. When using the test-retest method, the correlation coefficient obtained between total scores was also significant, and r= .70. Validity evidence in relation to other variables was investigated by checking the correlation between the CSI and Lipp's Stress Symptoms Inventory for Adults - LSSI (1984). A total of 100 individuals who responded both instruments participated in this research. Results showed a low but significant correlation between the total scores of the two instruments (r= .14, p= .05). Considering these results, the authors concluded that the instrument has satisfactory psychometric qualities (Savóia et al., 1996).

Dinis, Gouveia and Duarte (2011) expanded the research on coping assessment and suggested a measure with four factors, namely: rational, emotional, avoiding and distant/disconnected. In addition, more recent studies have found correlations between coping strategies and positive personal characteristics, such as problem-solving skills and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia (Park & Sung, 2016); positive emotions, resilience and mental health (Gloria & Steinhardt, 2016); academic adaptation (Luca, Noronha, & Queluz, 2018) and character strengths (Gustems-Carnicer & Calderón, 2016). Character strengths will be used in this study to check the instruments validity evidence based on its relationship with related constructs (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association and National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014).

Character strengths are defined as positive psychological traits that can push the individual forward, favoring a healthy development at the psychological, biological and social levels (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). In this sense, positive psychology proposes the existence of 24 strengths, namely: love, love of learning, appreciation of beauty, authenticity, self-regulation, kindness, bravery, citizenship, creativity, curiosity, hope, spirituality, impartiality, social intelligence, gratitude, humor, leadership, modesty, critical thinking, forgiveness, perseverance, prudence, judgment and vitality (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Harzer and Ruch (2015) sought relationships between Character Strengths and coping in a study with 214 participants, 143 of whom were female, aged 21 to 64 years (M= 38.28 years; SD= 10.51). Intellectual, emotional and interpersonal strengths were positively correlated with positive coping strategies. The authors concluded that character strengths are related to coping behaviors and, therefore, function as a protective factor for stressful situations.

Another point that has been increasingly highlighted in more recent studies (Ben-Zur, 2019; Greenaway et al., 2015) is the situational aspect of coping. In this sense, coping strategies should be assessed based on the context in which the stress episode occurs, the characteristics of the event itself, and the responses of the individuals involved, not by determining if strategies are good or bad, adaptive or maladaptive, which does happen in the CSI. The instrument proved to be a reliable measure (Savóia et al., 1996), but its validity evidence in Brazil was obtained more than 20 years ago. The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (AERA, APA, & NMCE, 2014) recommends that an instrument's validity evidence be constantly tested and updated to check if the measures are still reliable.

Given the above, it is important to check for new validity evidence for the CSI and assess whether its factor structure still holds. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Coping Strategies Inventory (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984), adapted to Portuguese by Savóia et al. (1996), through its validity evidence based on internal (factor) structure and relationship with other related variables (character strengths), as well as assessing the reliability of the instrument (AERA, APA, & NMCE, 2014). As a guiding hypothesis, it was expected that the eight-factor structure found by Savóia et al. (1996) was confirmed; the overall and factor scores of the Coping Strategies Inventory were correlated with each other and with the Character Strength measures; and the CSI showed good reliability measures.

Method

Participants

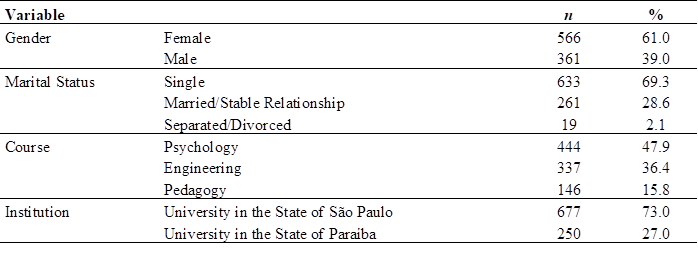

A total of 927 college students participated in this study, with an average age of 26 years (SD= 7.66), ranging from 18 to 59 years, 61% were female, and the majority was single (69.3%). The data analyzed were collected from Psychology (47.9%), Engineering (36.4%) and Pedagogy (15.8%) students. Data collection was conducted at a private institution in the interior of the state of São Paulo (73%) and another in the state of Paraíba (27%). The demographic profile as show in Table 1.

Instruments

Coping Strategies Inventory (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985). The purpose of the CSI is to assess the coping strategies used by individuals to deal with daily adverse situations. In this study, the Brazilian version adapted by Savóia et al. (1996) was used. The instrument contains 66 items that include thoughts and actions used to deal with internal or external demands of any stressful event, responded through a four-point Likert scale. In the version by Savóia et al. (1996) eight factors were found, as described in the introduction, with adequate reliability values according to test-retest (between .40 and .70). Cronbach's alpha values were not presented by the authors.

Character Strengths Scale (CSS) (Noronha & Barbosa, 2016). The goal of the instrument is to assess the 24 character strengths, namely: Love, Love of learning, Appreciation of beauty, Authenticity, Self-regulation, Kindness, Bravery, Citizenship, Creativity, Curiosity, Hope, Spirituality, Gratitude, Humor, Impartiality, Social intelligence, Leadership, Modesty, Critical thinking, Forgiveness, Perseverance, Prudence, Judgment and Vitality. The instrument consists of 71 items on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (nothing to do with me) to 4 (everything to do with me). The instrument has an alpha coefficient of .93, indicating high reliability (Noronha, Dellazzana-Zanon, & Zanon, 2015).

Data collection procedures

First, data collection authorization was requested from the institutions. Then, the project was submitted to the Ethics Committee of Universidade São Francisco, which was approved under CAAE Protocol 50003715.7.0000.5514. After approval, students were invited to participate in the study at the universities where data collection took place. Upon acceptance, they signed an Informed Consent Form. All participants received information on the goals of the study and the ethical issues involved. The instruments were applied in an alternating order to minimize learning and fatigue. The sessions were collective, in classrooms, and lasted approximately 30 minutes.

Data analysis procedure

In order to check the score distribution for each instrument, the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, and kurtosis and skewness indicators were calculated for each variable. Descriptive analyzes were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). All variables were normally distributed, according to the inspection of the number of modes, kurtosis and skewness values, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test (Marôco, 2014). In order to test the model proposed by Savóia et al. (1996), a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using the MPLUS software. The adjustment indices considered were: Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ 0.90), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, ≤ 0.06; with a 90% confidence interval), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI ≥ 0.95), statistical significance of the Chi-square test (p≤ .05) and Chi-square divided by the degree of freedom (x2/df < 3) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the program Factor was used, considering the following adjustment indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ 0.90), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.06; with a 90% confidence interval), Goodness-of-fit index (GFI ≥ 0.90) and Chi-square divided by the degree of freedom (x2/df < 3) (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The instrument's reliability was calculated using Cronbach's alpha, and analyzes were performed using Pearson's correlation test to check for potential correlations, since the sample was normally distributed. These measures were calculated using SPSS. For this study, correlation magnitude was classified as: weak (< .30), moderate (.30 to .59), strong (.60 to .99) or perfect (1.0) (Levin & Fox, 2004).

Results

Validity evidence based on internal structure

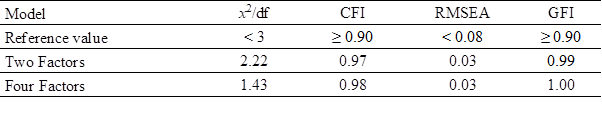

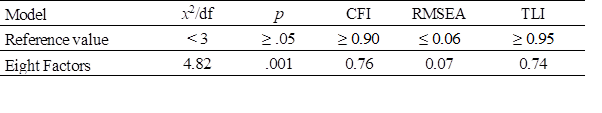

Table 2 shows the adjustment indices obtained after performing a confirmatory factor analysis of the Coping Strategies Inventory model proposed by Savóia et al. (1996). According to the results shown in Table 2, the proposed model did not present an adequate adjustment, since reference values were not within the expected range (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Thus, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed with the Coping Strategies Inventory to check what would be the structure found in a current Brazilian sample.

Table 2: Adjustment indices of the Coping Strategy Inventory model proposed by Savóia et al. (1996) found in CFA.

In EFA, it was first checked whether the data matrix was subject to factoring through the Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value, which was 0.90. Since this value was adequate (Damásio, 2012), the next step was to perform factor retention. The extraction method was Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (RDWLS), using the Promin rotation method. The number of factors was chosen according to the result of Parallel Analysis and the Hull Method (Ledesma, Ferrando, & Tosi, 2019). Parallel analysis indicated a solution with 4 factors and the Hull Method indicated a solution with 2 factors. Then, EFAs were performed on both solutions to check which one was the best theoretical and statistical fit, considering the adjustment indices for each one. The exclusion criteria for each EFA were removing items that did not saturate at least .30 or that presented a similar saturation in more than one factor, until no items needed to be excluded.

In the first round of the two-factor structure, six items were removed, as five (3, 5, 7, 10, 36) did not saturate in any of the factors, and one (65) showed a similar saturation in both. In the second round, one item (62) was removed, because it showed a similar saturation in both factors. In the third round, no items needed to be removed. In the end, the two-factor structure showed 31.37% of total explained variance and all adjustment indices had adequate values (Hu & Bentler, 1999), as shown in Table 3.

In the first round of EFA for the four-factor structure model, eleven items (3, 9, 29, 34, 35, 48, 54, 63, 64, 65 and 66) were removed because they did not saturate the minimum value in any factor, and four items were removed (10, 26, 47, 50) for having a similar saturation. In the second round, two items were removed because they had a similar saturation (51, 62). In the third round, two more items were removed, one for not saturating (25) and another for presenting a similar saturation in 2 factors (40). In the fourth round, item 43 was removed because it had a similar saturation in two factors. Finally, in the fifth round no items needed to be removed. In the end, the four-factor structure showed 40.64% of total explained variance and all adjustment indices had adequate values (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

When comparing both models and considering the adjustment indices, total explained variance, and theoretical cohesion as proposed by Folkman and Lazarus (1980), the four-factor solution was chosen. Factors were renamed according to the theoretical proximity observed in groupings. The final structure found had 46 items. Factor 1 was interpreted as reflecting “Positive Reappraisal” (items 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 and 61), Factor 2 as “Distancing and Acceptance” (items 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 24, 32, 33, 37, 41, 44 and 53), Factor 3 as “Social Support” (items 7, 8, 22, 28, 31, 36, 42 and 45), and Factor 4 as “Confrontation and problem solving” (items 1, 2, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 27, 30, 38, 39, 46, 49 and 52).

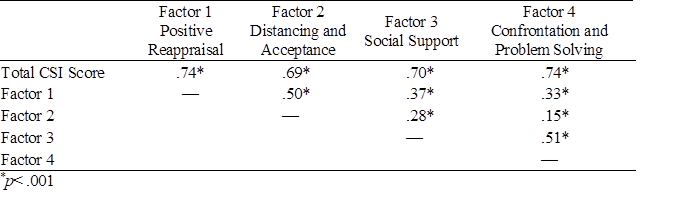

Table 4 shows the correlations between the total CSI score and its respective factors. All correlations were statistically significant. The highest correlations were those between the CSI Total Score and all its factors in general, which were strong. Factor 1 was moderately correlated with factors 2, 3 and 4, and Factor 3 was moderately correlated with factor 4. The lowest correlations were between Factor 2 and factors 3 and 4.

Table 4: Correlations between the Total Score of the Coping Strategies Inventory and the Scores of the Four Factors

In this study, for Factor 1 (7 items), α= .79; for Factor 2 (16 items), α= .79; for Factor 3 (8 items), α= .67; and for Factor 4 (15 items), α= .86. The overall Cronbach's alpha (α= .89) was excellent. All these coefficients can be considered adequate reliability values (Marôco, 2014).

Validity evidence based on relationships with other variables

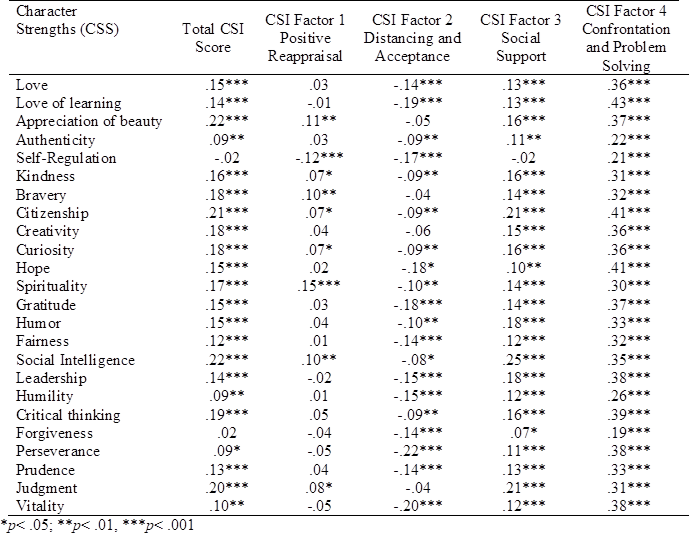

Table 5 shows the correlations between the factors and the total CSI score with Character Strengths. It can be noticed that the Total CSI Score showed statistically significant, positive and weak correlations with Character Strengths, and did not show a significant coefficient only with Self-Regulation and Forgiveness. The CSI Positive Reappraisal Factor showed statistically significant and positive correlations with Appreciation of beauty, Kindness, Bravery, Citizenship, Curiosity, Spirituality, Social Intelligence and Judgment, and negative correlations with Self-regulation, all of which were weak. Distancing and Acceptance showed a statistically negative and weak correlation with most Character Strengths, except for Appreciation of beauty, Bravery, Creativity and Judgment. In the Social Support Factor, all Character Strengths were also positively and weakly correlated, except for a single Character Strength, Self-Regulation. Finally, Confrontation and Problem Solving was significantly and positively correlated with all Character Strengths, and most of these correlations were moderate.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the CSI by checking its validity evidence, based on internal (factor) structure and relationship with other variables (character strengths), as well as assessing its reliability (AERA, APA, & NMCE). As a guiding hypothesis, it was expected that the eight-factor structure found by Savóia et al. (1996) was confirmed. However, when the model by Savóia et al. (1996) was tested, the adjustment indices found were not within the expected reference values. One hypothesis to explain this finding is the period that has passed between the testing of the model in 1996 and the current testing, indicating that some characteristic of the population may have changed. Regarding the sample, the study by Savóia et al. (1996) was conducted in the state of São Paulo, while this study was carried out both in São Paulo and in Paraíba. Therefore, the differences may be justified by the inclusion of a new state in data collection. Both studies were conducted with college students, however, Savóia et al. (1996) provide only the N of the sample, so it is not possible to make other comparisons or formulate hypotheses on potential reasons why the model was not confirmed. The authors did not provide data such as age, gender, whether the institution was public or private, socioeconomic characteristics, among other possibilities.

With regard to factor structure, since the model of Savóia et al. (1996) was not confirmed, a new exploratory factor analysis was performed to check what item factor structure would be found. After running the new exploratory factor analysis, the most adequate structure was a four-factor model: Positive Reappraisal, Distancing and Acceptance, Social Support, and Confrontation and Problem Solving. In the new solution, adjustment indices and reliability values were adequate, and factors were significantly correlated with each other and with the overall CSI score. This set of variables indicates that the new factor structure shows validity evidence based on internal structure (AERA, APA, & NMCE, 2014).

When comparing the factor structure obtained in this study with the structure of Savóia et al. (1996), it can be noticed that the factors Accepting Responsibility and Self-control were eliminated in the new exploratory factor analysis. For the Self-control factor, the only item that has remained was factor 14, which was relocated to the Distancing and Acceptance factor in the new version. Item 14, which says “I tried to keep my feelings to myself”, is theoretically justified in the factor that combines Distancing and Acceptance. One hypothesis to explain why Self-control items have been almost entirely eliminated is that individuals can use stress coping strategies without necessarily having self-control. Accepting Responsibility items, which involve recognition of guilt, are also requirements for the manifestation of stress coping strategies. Simply accepting that some situations that cannot be changed can be a strategy in itself, but responsibility, especially in the university context, requires further actions, which may justify the extinction of the factor (Greenaway et al. 2015).

With regard to the other factors, Positive Reappraisal and Social Support were maintained, while Distancing, Acceptance, and Confrontation and Problem Solving, which were four factors, were combined and became two. Escape-Avoidance items were divided between Positive Reappraisal and Distancing and Acceptance in the current version. This is relevant because the Escape-Avoidance strategy may be related either to a process of distancing, when the individual does not want to deal with something, or to a process of reassessing the situation to understand if escape-avoidance is the best option to face the source of stress (Greenaway et al., 2015).

After verifying the new CSI factor structure, it was assessed whether it showed validity evidence based on relationships with other variables (in this case, character strengths). Results showed that most character strengths were positively correlated with the total CSI score, indicating that coping strategies are related to the presence of character strengths. These data corroborate the study by Gustems-Carnicer and Calderón (2016) and Harzner and Ruch (2015), indicating that people with more character strengths also find it easier to develop coping strategies to deal with adverse situations.

With regard to factors, Factor 1 - Positive Reappraisal refers to the coping strategy aimed at controlling sadness-related emotions, as a form of reinterpretation, growth and personal change after a conflict situation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984b). It was the factor with the least significant correlations, all of which were weak. One explanation for this is that, while the factor refers to the ability to face sadness-related emotions, character strengths refer to positive personality characteristics, more associated with subjective well-being (Niemiec, 2014).

The CSI Distancing and Acceptance factor showed a statistically negative correlation with most character strengths. Behaviors related to Distancing and Acceptance were negative, as they refer to avoidance behaviors in stressful situations (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984b), while character strengths are positive and contribute to help individuals and society to thrive (Seider, Jayawickreme, & Lerner, 2017). Since they are negative, they can often become maladaptive, going in the opposite direction of the precepts of character strengths, because if adverse situations were faced, they could be circumvented (problem-focused coping) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984b). These indices suggest that, the more the strengths related to emotional qualities stand out, the better the coping strategies. McCrae and Costa (1986) reported that people with high levels of well-being use coping behaviors such as rational action, seeking help, drawing strength from adversity, and faith. Thus, coping theories are based on the idea that, in order to deal with problems, happy people trigger thoughts and behaviors that are adaptive and useful, while unhappy people, on average, face difficulties in a more destructive way (Diener, Suh, & Oishi, 1997; Greenaway, 2015).

The CSI Social Support factor was positively correlated with most character strengths. This result can be explained by the notion that people who have more character strengths are able to obtain more social support in their daily lives by becoming “easier” people to live with. Self-regulation had a coefficient equal to zero, which can be explained by the fact that it involves the individual's ability to behave effectively when facing adverse events, while social support involves other people, which does not necessarily occur when the person uses self-regulation in a given situation. The previous example fits here, a college student may decide to wake up early every day to study and do well in a test (behavioral self-regulation and problem-focused coping), but if they do it individually, without the help of others, they will have no social support, which justifies the lack of correlation with this character strength in this specific case.

The Confrontation and Problem-Solving factor showed a statistically significant correlation with all character strengths, being the factor with the highest number of moderate correlations, which makes theoretical sense, as it reflects the act of confronting a stressful situation. Therefore, this correlation indicates that the more developed the character strengths, the more individuals can manage adverse situations. These data confirm the studies by Harzner and Ruch (2015) and indicate that people who have stronger character strengths also find it easier to develop problem-solving and confrontation strategies. Finally, given the above and considering the results obtained, it can be postulated that the instrument also presents validity evidence based on relationships with other variables (AERA et al., 2014), since most character strengths were correlated with CSI measures, confirming the initial hypothesis of this study.

The character strengths that did not show any correlation were Self-Regulation and Forgiveness. Emotional self-regulation is the ability to moderate attention and behaviors arising from different circumstances and events (Peterson & Seligman, 2014). In this sense, it seems that participants may have coping strategies in their repertoire, but they have difficulty in self-regulating their behavior. For example, a student may use coping strategies such as praying, crossing fingers, thinking positive, among others, to try to do well in an exam, but not be able to get organized to study (behavioral self-regulation). To some extent, this information corroborates the exclusion of Self-control, as these factors have a similar content. Thus, in addition to its items not being retained in the source factor (Savóia et al., 1996), the correlation between self-regulation and the total CSI score was null.

With regard to Forgiveness, this result also makes theoretical sense, as a person may have difficulty in forgiving others, but at the same time have numerous coping strategies in their daily repertoire. In addition, considering the study sample, a college student who cannot forgive their classmate can probably develop coping strategies to do well in the academic context, such as waking up early to study, organizing group work, and thinking positive (Gustems-Carnicer & Calderón, 2016).

Final Considerations

Considering the objective of this article was to investigate the validity evidence of the Coping Strategies Inventory, results point to important evidence indicating that the data are relevant to understand the college students’ sample. Validity evidence based on internal structure and relationship with other variables was found. However, the structure did not corroborate the original version of the instrument, raising a new factor structure suggestion, which is one of the main contributions of this study. Furthermore, this study contributed to updating the instrument's format, as the last study aimed at checking its psychometric properties was conducted more than twenty years ago (Savóia et al., 1996).

However, even considering these positive results, the data must be taken with reservations, since data collection was conducted only with college students, which is a limitation. Therefore, a suggestion for future studies would be to expand the investigation scope beyond the academic context and with greater age variability. It would also be important to check if the factor structure remains the same for other samples. Another possibility would be to collect data in different ways, not only through self-administered questionnaires, such as conducting interviews to include participants with less or no education who would not be able to respond without assistance.

Finally, it would also be important to analyze the relationship between CSI scores and other external variables, such as those already established in the literature: stress, depression, anxiety, among others. Given the above, results indicate that this study has contributed to update the validity evidence of CSI and that further research is needed to expand this evidence.

REFERENCES

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education (AERA, APA, & NMCE). (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, EUA: American Educational Research Association. [ Links ]

Ben-Zur, H. (2019) Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. Shackelford (Orgs.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp. 1-4). Cham, Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_2128-1 [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., & Seize, M. M. (2017). Construção e adaptação de instrumentos psicológicos. In B. F. Damásio & J. C. Borsa (Orgs), Manual de desenvolvimento de instrumentos psicológicos (pp. 21-43). São Paulo, SP: Vetor. [ Links ]

Bramsen, I., Bleiker, E., Eveline, M. A., Triemstra, A. H., Mattanja, Van-Rossum, Sandra, M. G., et al. (1995). A Dutch adaptation of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire: Factor stucture and psychometric properties. Anxiety. Stress and Coping an International Journal, 8(4), 337-352. [ Links ]

Corti, E. J., Johnson, A. R., Gasson, N., Bucks, R. S., Thomas, M. G., & Loftus, A. M. (2018). Factor Structure of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s Disease, 2018, 1-7. doi:10.1155/2018/7128069. [ Links ]

Coyne, J. C., Aldwin, C., & Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Depression and coping in stressful episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 439-447. [ Links ]

Damásio, B. F. (2012). Uso da análise fatorial exploratória em psicologia. Avaliação Psicológica, 11(2), 213-228. [ Links ]

Dinis, A., Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2011). Contributos para a Validação da Versão Portuguesa do Questionário de Estilos de Coping. Psychologica, 1(1), 35-62. [ Links ]

Falkum, E., Oiff, M, & Aasland, O. (1997). Revisiting the factor structure of the Ways of Coping Checklist: a three-dimensional view of the problem-focused coping scale. A study among Norwegian physicians. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(2), 257-267. [ Links ]

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of health and social behavior, 21(3), 219-239. [ Links ]

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: A study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150-170. [ Links ]

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R., & DeLongis, A. (1986). Appraisal, coping, health status and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 50, 571-579. [ Links ]

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Manual for the ways of coping questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [ Links ]

Gloria, C. T., & Steinhardt, M. A. (2016) Relationships among positive emotions, coping, resilience and mental health. Stress Health, 32(2), 145-156. doi: 10.1002/smi.2589 [ Links ]

Greenaway, K. H., Louis, W. R., Parker, S. L., Kalokerinos, E. K., Smith, J. R., & Terry, D. J. (2015). Measures of Coping for Psychologica l Well-Being. Measures of Personality and Social Psychologica l Constructs, 1, 322-351. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-386915-9.00012-7 [ Links ]

Gustems-Carnicer, J., & Calderón, C. (2016). Virtues and character strengths related to approach coping strategies of college students. Social Psychology of Education, 19(1), 77-95. [ Links ]

Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2015). The relationships of character strengths with coping, work-related stress, and job satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 165. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00165. [ Links ]

Hirsch, C. D., Barlem, E. L. D., Almeida, L. K. D., Tomaschewski-Barlem, J. G., Figueira, A. B., & Lunardi, V. L. (2015). Estratégias de coping de acadêmicos de enfermagem diante do estresse universitário. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 68(5), 783-790. [ Links ]

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new99 alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984a). Stress appraisal and coping. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984b). Coping and Adaptation. Em W. D. Gentry (Org.), Handbook of Behavioral Medicine (pp. 282-325). New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S., & Smith, C. A. (1988). Knowledge and appraisal in the cogmtton-emotion relationship. Cognition and Emotion, 2, 281-300. [ Links ]

Ledesma, R. D., Ferrando, P. J., & Tosi, J. D. (2019). Uso del Análisis Factorial Exploratorio en RIDEP. Recomendaciones para Autores y Revisores. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación - eAvaliação Psicológica , 52(3), 173-180. doi: 10.21865/RIDEP52.3.13 [ Links ]

Levin, J., & Fox, J. A. (2004). Estatística para ciências humanas. São Paulo, SP: Pearson. [ Links ]

Liew, C. V., Santoro, M. S., Edwards, L., Kang, J., & Cronan, T. A. (2016). Assessing the Structure of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire in Fibromyalgia Patients Using Common Factor Analytic Approaches. Pain research & management, 2016, 7297826. doi:10.1155/2016/7297826 [ Links ]

Lipp, M. E. N. (1984). Manual do Inventário de Sintomas de Stress para Adultos de Lipp (ISSL). São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Luca, L., Noronha, A. P. P., & Queluz, F. N. F. R. (2018). Relações entre estratégias de coping e adaptabilidade acadêmica em estudantes universitários. Revista Brasileira de Orientação Profissional, 19(2), 169-176. doi: 1026707/1984-7270/2019v19n2p169 [ Links ]

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise estatística com o SPSS statistics. Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal: Report Number. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L., & Zanon, C. (2015). Internal Structure of the Strengths and Virtues Scale in Brazil. Psico-USF, 20(2), 229-235. doi:10.1590/1413-82712015200204 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Barbosa, A. J. G. (2016). Forças e Virtudes: Escala de Forças de caráter. In C. S. Hutz (Org.), Avaliação em Psicologia Positiva: Técnicas e Medidas (pp. 21-43). São Paulo: CETEPP. [ Links ]

Pais-Ribeiro, J., & Santos, C. (2001). Estudo conservador de adaptação do Ways of Coping Questionnaire a uma amostra e contexto portugueses. Análise Psicológica, 19(4), 491-502. [ Links ]

Park, S. A., & Sung, K. M. (2016) Effects on Stress, Problem Solving Ability and Quality of Life of as a Stress Management Program for Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: Based on the Stress, Appraisal-Coping Model of Lazarus & Folkman. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 46(4), 583-597. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2016.46.4.583 [ Links ]

Savóia, M. G., Santana, P. R., & Mejias, N. P. (1996). Adaptação do Inventário de Estratégias de Coping de Folkman e Lazarus para o português. Psicologia USP, 7(1), 183-201. [ Links ]

Seider, S., Jayawickreme, E., & Lerner, J. V. (2017). Theoretical and Empirical Bases of Character Development in Adolescence: A View of the Issues. Journal of youth and adolescence. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0650-3 [ Links ]

Vitaliano, P.P., Russo, J., Can, J. E., Maiuro, R.D., & Becker, J. (1985). Ways of Coping Checklist: Revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 20, 3-26. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2001_1. [ Links ]

How to cite: Luca, L., Noronha, A.P.P., Queluz, F.N.F.R., & Angeli dos Santos, A.A. (2020). New validity evidence for the Coping Strategies Inventory. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2319. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2319

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. L.L. has contributed in a,b,c,d; .A.P.P.N. in a,c,e; F.N.F.R.Q. in c,d,e; A.A.A.S. in c,d.

Correspondence: Luana Luca. Centro Universitário de Jaguariúna. Rua Ezio Wagner da Silva, 89, apto 63, Campinas - SP, Brasil. E-mail: luanaluca@gmail.com. Ana Paula Porto Noronha. Universidade São Francisco. Rua Waldemar Cesar da Silveira, 105, Jardim Cura D’ars, Campinas - SP, Brasil. E-mail: ana.noronha8@gmail.com. Francine Náthalie Ferraresi Rodrigues Queluz. E-mail: francine.queluz@gmail.com. Acácia Aparecida Angeli dos Santos; e-mail: acacia.santos@usf.edu.br

Received: September 26, 2019; Accepted: September 15, 2020

texto em

texto em