Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 01-Sep-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2283

Original articles

Negative and open marital communication: interdependent model of actor/partner effect in marital adjustment

1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia Clínica, Centro de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos- UNISINOS- Brasil

Communication is essential for assessment and intervention in marital psychotherapy. For that matter, it was investigated whether negative and open marital communication impact the marital adjustment of heterosexual couples. This is a quantitative, cross-sectional, correlational, and explanatory study. A total of 231 couples residing in the Southern region of Brazil were assessed. Participants answered the Communication Questionnaire and the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (R-DAS). The data were analyzed on a dyadic basis using the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) and indicated that negative communication causes a greater impact than open communication in the marital adjustment of husbands and wives, since it caused actor and partner effects. Open communication caused only the actor effect for husbands and wives. The results were discussed in the light of the scientific literature considering the possible implications for the clinical area and for the research.

Keywords: communication; marital relationship; marital adjustment

A comunicação é imprescindível à avaliação e intervenção em psicoterapia conjugal. Nesse sentido, foi investigado se a comunicação conjugal negativa e aberta impactam no ajustamento conjugal de casais heterossexuais. Trata-se de um estudo quantitativo, transversal, correlacional e explicativo. Foram avaliados 231 casais residentes no Sul do Brasil. Os participantes responderam o Communication Questionnaire e o Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale R-DAS. Os dados foram analisados de forma diádica por meio do Actor Partner Interdependence Model - APIM e indicaram que a comunicação negativa provoca impacto superior à comunicação aberta no ajustamento conjugal de maridos e esposas, já que provocou efeitos ator e parceiro. A comunicação aberta provocou somente o efeito ator para maridos e esposas. Os resultados foram discutidos à luz da literatura científica considerando as possíveis implicações para a área clínica e para a pesquisa.

Palavras-chave: comunicação; relacionamento conjugal; ajustamento conjugal

La comunicación es indispensable para la evaluación e intervención en psicoterapia conyugal. En ese sentido, fue investigado si los estilos de comunicación conyugal negativa y abierta impactan en el ajuste conyugal de parejas heterosexuales. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo, transversal, correlacional y explicativo. Se evaluaron 231 parejas residentes en el Sur de Brasil. Los participantes respondieron el Communication Questionnaire y el Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale R-DAS. Los datos fueron analizados de forma diádica a través del Actor Partner Interdependence Model - APIM e indicaron que la comunicación negativa produce un impacto superior a la comunicación abierta en el ajuste conyugal de maridos y esposas, pues provocó los efectos actor y socio. La comunicación abierta fue predictora solamente del efecto actor para los esposos y las esposas. Los resultados fueron discutidos a la luz de la literatura científica y en consideración de las posibles implicaciones para el área clínica y para la investigación.

Palabras clave: comunicación; relación conyugal; ajuste conyugal

Introduction

Communication is essential to human existence, and it is consensually relevant in couple psychotherapy, as pointed out by a systematic review of the Brazilian and international literature (Costa, Delatorre, Wagner, & Mosmann, 2017). Marital education programs (Blanchard, Hawkins, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2009; Epstein, Warfel, Johnson, Smith, & McKinney, 2013; Lau, Tao, Randall, & Bodenmann, 2016; Neumann & Wagner, 2017; Neumann, Wagner, & Remor, 2018), and programs for the assessment of processes and results in couple psychotherapy (Baucom, Baucom, & Christensen, 2015; Tilden, Hoffart, Sexton, Finset, & Gude, 2011; Worthington Jr. et al., 2015), aiming to improve, among other aspects, the communication skills of the partners, have pointed out consistent evidences of the positive effects of the interventions, increasing marital adjustment levels.

The analysis of communication in human relationships, and the concepts of circularity and feedback first appeared at the Palo Alto School (USA) through contributions from authors such as Gregory Bateson, Paul Watzlawick, Janet Beavin, Don Jackson, Jay Haley, John Wekland, among others, based essentially on a systemic approach (Boscolo & Bertrando, 2013; Mattelart, 2009). According to these authors, the sender and the receiver of the message play an equally important role in the course of the interaction (Mattelart, 2009; Watzlawick, Beavin, & Jackson, 1973). In this perspective, the relational and interactional processes and the context in which the exchange of messages occurs must be the main aspects of analysis at the expense of separately observing individual variables (Costa, Cenci, & Mosmann, 2016; Féres-Carneiro & Diniz-Neto, 2010).

Even if an individual has the intention of not expressing him or herself verbally, he or she will be communicating something, a precept of the impossibility of not communicating. Reporting (information, content) and command (order, connotation) are the main aspects that make up communication. The former refers to the transmission of information, data, etc., and the latter, considered metacommunication, is related to the intention, underlying purpose, directly interfering with the way that the message will be received (Watzlawick et al., 1973). According to the authors, if the relationship between the spouses is harmonious, communication becomes a secondary aspect. However, if it is a conflicting relationship, more effort will have to be spent for the content to be evident. Therefore, the characteristics of the communication between the couple are relevant both for the assessment of marital dynamics and for intervention in a clinical context (Baucom et al., 2015; Tilden et al., 2011; Worthington Jr. et al., 2015).

Communication, if negative, will occur through accusatory behaviors, dominance, interruptions, withdrawal, indifference, hostile tone of voice, and a context of negative interactions that tend to worsen, causing escalating conflicts. Being positive, communication occurs through empathy, understanding, validation, and openness to speaking clearly and sincerely about personal, marital, professional, among other problems and interests (Van den Troost, Vermulst, Gerris, & Matthijs, 2005).

In addition, objectivity, clarity, the ability to listen, to honestly share thoughts and feelings, and to avoid criticism are characteristics of positive marital communication and skills for a satisfactory relationship (Epstein et al., 2013). To test this argument, Epstein et al. assessed, in a sample of 2201 participants, seven factors considered important skills in a romantic relationship. The assessed factors were communication, conflict resolution, knowledge about the partner, life skills, self-management, sex/intimacy, and stress management. The results of the study confirmed that marital education programs are beneficial to couples, as participants in communication and conflict resolution training programs scored higher in the assessed skills. Just as other studies point out (Baucom et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2005; Markman, Rhoades, Stanley, Ragan, & Whitton, 2010; Tilden et al., 2011; Worthington Jr. et al., 2015), Epstein’s study indicated that communication skills are predictors of higher levels of satisfaction and marital adjustment.

In the study by Markman et al. (2010), the quality of communication before marriage, and during the first five years of marriage was assessed in regard to conflict and divorce in a sample of 210 North American couples. The results confirmed what the authors called the “negativity effect”, in which negative communication is a stronger risk factor than positive communication is a protective factor, as also found by Johnson et al. (2005). Negative communication was strongly associated with the risk of divorce, and the decline in marital quality and adjustment. The authors explain that this result may indicate that people are more sensitive to negative experiences in the relationship and in life, since these can effectively hurt more and, therefore, are selected and kept under check at the expense of the positive aspects.

In addition, the results of the study by Markman et al. (2010) support the assumption that it is necessary to pay attention to pre-interactional factors, observing the appropriate time to talk about conflicts (Costa & Mosmann, 2015), and to replace negative expressions of anger and criticism with expressions of affection and admiration that impact on long-term conjugal interaction (Féres-Carneiro & Diniz-Neto, 2010) and promote cooperation between the pair (Paleari, Regalia, & Fincham, 2010). Other studies also point out that conciliatory communication contributes to overcoming possible difficulties inherent to the different stages of the conjugal life cycle (Luz & Mosmann, 2018; Rech, Silva, & Lopes, 2013).

A research conducted through an online questionnaire with a sample of 266 people in stable heterosexual relationships in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, assessed and compared the communication of individuals with children in different stages of the family life cycle, and with different levels of functionality measured through cohesion and marital adaptability and adjustment. The results showed that negative communication is an aspect that influences different stages of marriage, especially the early years. It also indicated that men used the negative communication style more, while women preferred the open communication style (Luz & Mosmann, 2018).

In Berkeley, California (USA), Seider, Hirschberger, Nelson, and Levenson (2009) assessed marital communication and interaction patterns through the personal pronouns I/me, you, and we/us, in a research that analyzed fifteen minutes of conversation of 154 couples and measured the quality of interaction, affection, and marital satisfaction. The results provided evidence that the use of the pronoun "we/us" reflects interdependence, shared responsibility, partnership, and constructive resolution of conflicts, being also associated with high levels of positive affect, low levels of negative affect and cardiovascular excitement, being stronger to the message recipient - partner effect. The separation pronouns "I/me" and "you" reflected withdrawal, individualism, high levels of marital dissatisfaction, and negative affection and interaction, substantial effects for both actor and partner. The authors agree that satisfied couples more often use reparation attempts that prevent or reduce negativity during discussions, accept the spouse's influence and the existence of insoluble problems, and are solicitous to the partner, validating their attempt of interaction (Costa & Mosmann, 2015; Driver, Tabares, Shapiro, & Gottman, 2016; Madhyastha, Hamaker, & Gottman, 2011).

In the same investigative direction, Madhyastha et al. (2011) analyzed 15 minutes of interaction of 254 couples, at six-second intervals, assessing how much a spouse's emotional balance state was able to influence that of the partner based on the previous interval. Couples whose levels of marital satisfaction were low remained in a context of negative reciprocity for longer, and those with higher levels of satisfaction established an atmosphere of agreement and greater positivity during the conflict, greater approval, and less disagreement and criticism. The authors found the reciprocal influence between partners, an aspect that Driver et al. (2016) point out as necessary in a marital relationship, although the interaction must occur through approximately five positive behaviors for each negative behavior. This pattern was proposed based on extensive studies conducted by researchers from the Gottman laboratory and differentiates satisfied couples from dissatisfied and divorced couples.

The theoretical and empirical assumptions presented show the relevance of communication in the marital relationship. This is an aspect that makes it possible to observe the characteristics of the interaction between spouses (Costa et al., 2016; Féres-Carneiro & Diniz-Neto, 2010), in which couples can invest in order to prevent future problems, participating, for example, in pre- and post-marriage conjugal education programs (Blanchard et al., 2009; Epstein et al., 2013; Lau et al., 2016; Neumann & Wagner, 2017; Neumann et al., 2018). Furthermore, in evidence-based couple psychotherapies, communication between spouses is regarded, in studies, as one of the main focuses of the intervention, promoting positive results (Baucom et al., 2015; Costa et al., 2017; Tilden et al., 2011; Worthington Jr. et al., 2015).

Communication studies have mainly used marital adjustment as an outcome variable (Belanger, Laporte, Sabourin, & Wright, 2015; Driver et al., 2016; Holley, Haase, & Levenson, 2013; Worthington Jr. et al., 2015), the relationship dimension that involves cohesion, consensus, and marital satisfaction (Hollist et al., 2012). In the clinical context, the results of studies of this nature may guide interventions aimed at increasing levels of marital adjustment (Madhyastha et al., 2011; Markman et al., 2010; Seider et al., 2009) and preventing intimate partner violence triggered by communication problems (Hammett, Castañeda, & Ulloa, 2016).

In Brazil, there is a scarcity of research on marital communication (Luz & Mosmann, 2018), dyadic analyzes, for example, were found only in international studies (Hammett et al., 2016; Madhyastha et al., 2011; Markman et al., 2010; Seider et al., 2009). As for the investigation of self-declared heterosexual couples, there is scientific evidence in opposite directions regarding the correspondence between the independent variables of husbands and wives about the marital adjustment outcome variable of both spouses. Some studies suggest that men are more skilled and resolute when it comes to problem solving (Delatorre et al., 2017; Delatorre & Wagner, 2018; Yaşın & Sunal, 2016), which reverberates positively in the relationship. In contrast, women tend to be more empathetic and to express their feelings more easily (Costa & Mosmann, 2020; Deitz et al., 2015). Other studies are inconclusive as to the effect of the gender independent variable on marital adjustment, that is, whether it is the husband (Iveniuk et al., 2014), or the wife (Terveer & Wood, 2014), who most interferes in the marital dynamics. Therefore, studies reveal differences associated with gender and the need for more scientific evidence to clarify if, in heterosexual marital dyads, the communication impact of the actor/partner factor on marital adjustment varies or not.

In addition, the appreciation of the phenomenon needs to employ more consistent methods of investigation and assessment, considering communication as an interactional phenomenon that feeds itself (Boscolo & Bertrando, 2013; Costa et al., 2016; Féres-Carneiro & Diniz-Neto, 2010; Mattelart, 2009; Watzlawick et al., 1973). Therefore, dyadic analysis that consider the Actor/Partner effects in Interdependent Models (APIM) (Andrade, Cassepp-Borges, Ferrer, & Sanchez-Aragón, 2017; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) can contribute to a more robust assessment of the impact of different types of communication on marital adjustment.

Through the APIM, it is possible to identify whether the communication style of one of the spouses impacts on the marital adjustment of the other spouse (partner effect) and on the individual's marital adjustment (actor effect) (Andrade et al., 2017; Kenny et al., 2006). Still, in these analyses, it is possible to assess the magnitude of the impact of the independent variables on the outcome variables, and the strength of the correlations between them.

Based on the above, the present study analyzed whether negative and open marital communication styles impact on the marital adjustment of heterosexual couples. The impact that communication styles have on marital adjustment of husbands and wives will be assessed, considering the following hypotheses: H1 = the actor/woman effect of negative communication on marital adjustment will be greater than the actor/man effect; H2 = the actor/woman effect of open communication on marital adjustment will be lower than the actor/man effect; H3 = the partner/woman effect of negative and open communication on marital adjustment will be greater than the partner/man effect.

Materials and Method

Design

The study features a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional nature, and a correlational and explanatory design. It is intended to explain, based on a theoretically proposed model, the cause of the phenomenon investigated, testing the hypotheses raised (Creswell, 2010).

Participants

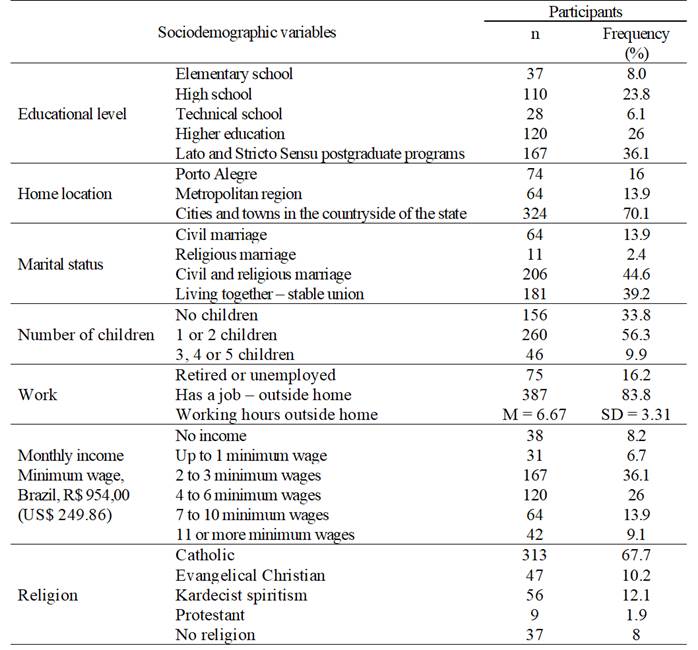

A total of 231 heterosexual couples (462 individuals) participated in this study. The minimum age of the respondents was 18 and the maximum was 79 (M= 41.41; SD= 12.40), and the length of relationship ranged from 6 months to 53 years (M= 15.15; SD= 12.05). Other sociodemographic information of the sample is shown in Table 1.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Questionnaire: the survey of the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants was carried out through a questionnaire with fifteen questions that investigated: age, sexual orientation, place of residence, marital status, length of relationship, existence of a previous relationship, length of previous relationship, educational level, profession, whether the person work outside home, their workload, personal income, number of children, and religion.

Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale - R-DAS (Busby, Christensen, Crane, & Larson, 1995; validado por Hollist et al., 2012). The reduced version of the marital adjustment scale has 14 items, with three factors. The first factor, consensus, has six items that assesses the level of agreement/disagreement between partners regarding different topics on a five-point Likert scale ranging from five (“we always agree”) to zero (“we always disagree”). The satisfaction factor has four items that measure the frequency with which the partners fight, talk about divorces, among other topics, on a five-point Likert scale that ranges from zero (“always”) to five (“never”). The third, cohesion, has four items that assess how often the partners perform different activities together. These items must be scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from zero (“never”) to five (“more than once a day”), with the exception of item 11 which is scored on a four-point Likert scale, being four (“everyday”) and zero (“never”). In the translation and validation for Brazil, a Cronbach’s Alpha of .90 for total adjustment, .81 for the consensus factor, .85 for the satisfaction factor, and .80 for the cohesion factor. In the present study, Cronbach’s Alpha values for total adjustment and for the consensus, satisfaction, and cohesion factors were, respectively, .84, .77, .78, and .80, for men, and .87, .72, .83, and .82 for women.

Communication Questionnaire (Van den Troost et al., 2005; translated by Luz & Mosmann, 2018). It is a scale composed of fifteen items divided into two factors. The first factor has nine items that assess negative communication, and the second has six items that assess open communication. The respondent scores, on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from one (“not applicable”) to seven (“very applicable”), the extent to which each statement corresponds to the way the marital partners communicate. In the Brazilian study for the scale adaptation, a Cronbach's Alpha of .74 for negative communication, and .70 for open communication (Luz & Mosmann, 2018). In the original study, Cronbach's Alpha of .83 and .80 was found for men and women, respectively, in the negative communication factor, and .67 and .71 in the open communication factor. In this study, Cronbach's Alpha values of the negative and open communication factors were .86 and .81 for men, and .83 and .83 for women, respectively.

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection took place in the city of Porto Alegre and its metropolitan region, and cities in the rural areas of the state of Rio Grande do Sul to make sure that the sample was heterogeneous. The responsible researcher contacted the couples via phone, WhatsApp, and e-mail, contacts were provided by their acquaintances, therefore, data collection was performed through convenience. In the first communication, the objectives of the study, and the risks and benefits involved in participation were explained. If they were interested and available, another day was be scheduled for collection of data at the couple's location of preference, which varied between home and work. The procedure took an average of 60 minutes and involved reading the Informed Consent Form (ICF), clarifying doubts, and signing the term in four counterparts, with each spouse keeping one copy, returning the other to the researcher who would keep the documents separately from the questionnaires, avoiding the identification of the participants based on the ICF. Finally, the research questionnaire was completed, which was separately carried out by the couple, that is, without one having access to the other's answers. In addition, each research questionnaire was identified with the letter corresponding to gender, “H” for men and “M” for women, and a number corresponding to the dyad, as an example: Envelope 1 - Questionnaires H1 and M1; Envelope 2 - H2 and M2 questionnaires, etc.

Ethical Considerations

The present study was submitted to assessment by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (UNISINOS, University of the Vale do Rio dos Sinos). The procedures adopted strictly followed what is contained in Resolution 510/2016 of the Conselho Nacional de Saúde (CNS, National Health Council), considering the pertinent ethical and scientific foundations, as stated in the ICF. Among the information provided in the term was: free and voluntary participation in the research, possibility of withdrawal without harm, risks and benefits, guarantee of confidentiality and protection of information, the right to request the results of the study, psychological assistance and referral in case of the development of mental issues caused by the participation in research, and the contact of the researchers in charge.

Data analysis

Initially, a database was built using the SPSS 25.0 program (Statistical Package for Social Science), the sample's normality criteria were confirmed, and then descriptive analysis were performed to calculate percentages, means, and standard deviation. A second database was also built, organized in its own structure for conducting dyadic analysis. In this format, different from the usual one where each individual corresponds to a row in the database, each couple corresponds to a row in the database. There are, therefore, twice as many variables, and the reduction of the sample in half (Andrade et al., 2017). To perform the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) analysis, the Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software, v22.0, was used, in which Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is performed, consisting of a multivariate data analysis technique where it is possible to test simultaneous relations between dependent and independent variables through theoretical multiple relation models (Byrne, 2010; Pilati & Laros, 2007).

The first step of the analysis was the verification of the interdependence or non-independence between the members of the dyad since, in romantic relationships, a shared context is expected and, therefore, reciprocal influence between the partners. The presence of interdependence makes it possible to indicate the influence between the dyad and include both the individual and the couple as the unit of analysis. Considering the pairing of the couples in dyadic models, interdependence was assessed by means of Pearson's correlation coefficient of the responses for the same set of variables (Kenny et al., 2006).

In the second step, using the database organized in an individual structure, Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Maximum Likelihood) were carried out to verify the parameter invariance between the groups of men and women, that is, if the constructs assessed are the same for both members of the dyad. Through the invariance test, it is possible to infer that the items that make up a given factor have the same factor loading for both groups (Damásio, 2013). According to Byrne (2010), to assume the invariance between the groups, a difference of no more than 0.01 in the CFI adjustment index of the models is acceptable.

In the third step, the theoretically proposed APIM model was tested by checking the effects of negative and open communication on marital adjustment, considering the effects of actor/man and actor/woman, and the effects of partner/man and partner/woman. Initially, the means of each of the factors assessed were calculated using the sum of the items and, later, the model was tested. The following model fit indices were used: Chi-square (χ²), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with a 90% confidence interval. The estimation method was the Maximum Likelihood (ML). Low Chi-square values, greater than 0.900 for the CFI and the NNFI, and less than 0.080 for the RMSEA are acceptable and indicate a good fit of the model. It is suggested, preferably, adjustment indices above 0.950 for the CFI and the NNFI, and below 0.050 for the RMSEA (Byrne, 2010).

Results

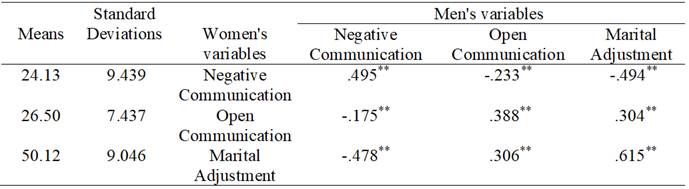

Through the initial tests, it was possible to infer the interdependence between the members of the dyad, as can be seen in Table 2, in which means, standard deviations, and correlations between the communication scales and the R-DAS for men and women are presented.

Table 2: Communication and Marital Adjustment: means, standard deviations and correlations (N = 462)

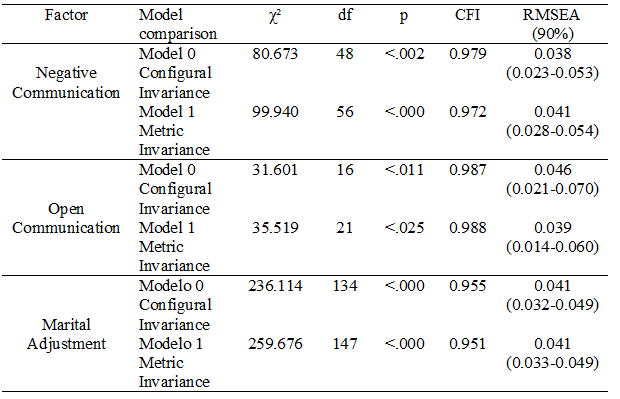

The factor load invariance test for both groups is shown in Table 3. When comparing the configural invariance in model 0 without restrictions and the metric invariance in model 1 with factor load restriction, it is verified that the difference in the comparison adjustment index (Comparative Fit Index - CFI), was not greater than 0.010 for any of the factors.

Table 3: Multi-Group Factorial of the Scales of Communication and the Marital Adjustment of Men and Women (N = 462)

Note: Model 0=not restricted, Model 1=factor load restriction, χ²= Chi-square, df=degrees of freedom, p=significance, CFI=Comparative Fit Index, RMSEA=Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

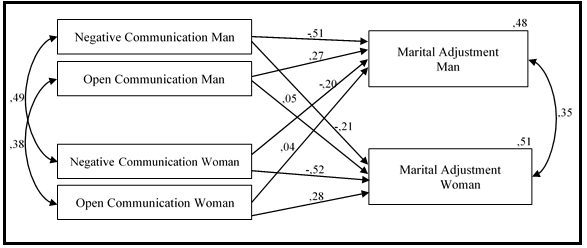

The interdependence tests and the Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis demonstrated that it is possible to continue the dyadic analysis by the APIM method. The final model, represented graphically in Figure 1, presented good adjustment rates, being possible to assess the impact of negative and open communication on the marital adjustment of the members of the dyad. The model's adjustment indices were: (χ2=21.326; df=4; p=0.000; CFI=0.965, NNFI=0.958; RMSEA=0.092 (90%CI=0.084-0.137)).

In addition to the adjustment indices, the APIM model allows estimating the covariance between the independent variables and between the errors of the dependent or outcome variables of men and women (Andrade et al., 2017). In the negative communication factor, there was moderate covariance (r=.49). In open communication, mild covariance (r=.38). Among the errors of the marital adjustment outcome variable, mild covariance (r=.35).

The magnitude of the regression prediction indicating the impact of the actor effect (variables independent of the individual interfering in his or her own marital adjustment) and the partner effect (variables independent of a spouse impacting on the spouse's adjustment), can be observed through the arrows that start from left to right in Figure 1. It appears that the actor/man effect of negative communication and open communication on marital adjustment was (B=-0.51; p=.001) and (B=0.27; p=.001), respectively, and the actor/woman effect of the same factors on marital adjustment was (B=-0.52; p=.001) and (B=0.28; p=.001).

Finally, the partner/man effect of negative and open communication styles on marital adjustment, that is, the impact that the husband's way of communicating has on his wife's marital adjustment, was (B=-0.21; p=.001) and (B=0.05; p=.227), respectively. The partner/woman effect of negative and open communication styles on the husband's marital adjustment was (B=-0.20; p=.001) and (B=0.04; p=.490). It is observed, in these results, that the actor/man effect and the actor/woman effect of negative communication on marital adjustment was moderate, and open communication was light. Analyzing the partner/man effect and the partner/woman effect of communication on marital adjustment, there is a slight magnitude for negative communication, and no prediction for open communication, considering p<.05.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to analyze whether negative and open communication styles impact on the marital adjustment of heterosexual couples. The results found through the APIM make it possible to understand relevant characteristics of the interaction between men and women who live in heterosexual marital relationships (Madhyastha et al., 2011; Markman et al., 2010; Seider et al., 2009).

The first aspect elucidated refers to the association between the couples' way of communicating. This is observed through the covariance between the husband’s and wife’s negative communication styles, in the same way as occurs with the open communication style and with the marital adjustment, with covariance between the errors. The result of these covariances indicates that, if there is a change in the way of communicating, negative and/or open, and in the marital adjustment of a member of the dyad, the change will cause a directly proportional change in the way of communicating and in the marital adjustment of the partner.

As mentioned in the introduction, it is necessary to investigate the interactional aspects when working with couples, since the main focus is on the most prominent characteristics about the way the partners relate and develop patterns of interaction that tend to repeat themselves (Costa et al., 2016; Féres-Carneiro & Diniz-Neto, 2010). The result indicates the interdependence between the members of the dyad, that is, the way of communicating from one partner interferes with the way of communicating from the other, either negatively or positively (open communication), an influence considered necessary by experts in the phenomenon (Driver et al., 2016; Madhyastha et al., 2011).

Interdependence can also be seen in marital adjustment. From a clinical perspective, this result could indicate that it is essential to assess the relational context in which marital problems and conflicts occur, as one partner tends to be a thermometer of what occurs with the other. In addition, this aspect corroborates the systemic assumption of feedback (circular causality), highlighting the need to consider the characteristics of communication when working with couples (Boscolo & Bertrando, 2013; Mattelart, 2009; Watzlawick et al., 1973). Another concept refers to the complementary character of communication. As postulated by Watzlawick et al. (1973), it is not correct to assume that one spouse causes the other to react in a linear way, but that both mutually create opportunities for this to be established and maintained. In this sense, negative communication generates more negative interactions, and vice versa.

The results of the analysis of the actor effect on marital adjustment indicated that the partners' way of communicating impacts the individual's own adjustment. It is noteworthy that the impact of negative communication was greater than the impact of open communication on the adjustment of men and women. This evidence indicates that an individual's communication style interferes with his or her levels of marital adjustment and, mainly, that negative communication tends to impact more, corroborating with other studies (Johnson et al., 2005; Markman et al., 2010) that attest the superiority of negative issues as risk factors, compared to positive issues as protective factors.

The partner/man and partner/woman effects of the independent, negative, and open communication variables on the marital adjustment outcome variables raise important reflections, since only the negative communication style affected marital adjustment, with an equivalent result for men and women. It is possible to find a basis for this result in the studies conducted by researchers from the Gottman laboratory (Driver et al., 2016). According to them, satisfied couples tend to have five positive interactions for each negative interaction compared to dissatisfied or divorced couples, who are unable to develop the same equation when interacting. Therefore, from this result, it is possible to conjecture that, to impact marital adjustment, the levels of positive (open) communication should be five times higher than the levels of negative communication, which may explain the lack of predictability of the latter on marital adjustment.

In addition to the partner effect occurring only for the negative communication style, when considering the results of the actor effect on marital adjustment, it is verified a higher impact of negative communication. Together, these data confirm the assumptions of renowned experts investigating the phenomenon (Watzlawick et al., 1973), that communication becomes a secondary element if it is spontaneous (positive), but, in contexts of conflicting interactions between spouses, the style of communication becomes evident, a concept that is also supported by empirical studies that indicate the preponderance of negative dimensions over positive ones in marital relationships (Johnson et al., 2005; Luz & Mosmann, 2018; Markman et al., 2010).

The results of the actor and partner effect were preponderant in relation to negative communication, confirming previous studies on the impact that this form of communication has on conjugality (Costa et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2005; Luz & Mosmann, 2018; Markman et al., 2010). This evidence may indicate that efforts undertaken in marital education programs and clinical interventions with couples should focus mainly on reducing negative communication and the characteristics of this type of communication (Van den Troost et al., 2005), and less on promoting skills of positive communication between partners, a different understanding from what was reported by Baucom et al. (2015) that constructive communication would provide more consistent effects in couple therapy than destructive communication.

Finally, the hypotheses that there would be differences between husbands and wives as to the actor/partner effect of negative and open communication on both spouses' marital adjustment have not been confirmed. Unlike what was found in other studies (Costa & Mosmann, 2020; Deitz et al., 2015; Iveniuk et al., 2014; Terveer & Wood, 2014), there was a similar impact of the independent variables of husbands and wives on the adjustment of both. In summary, the result raises doubts about the effective difference between men and women when they are involved in a stable marital relationship, and start to influence each other, in a way that it is difficult to determine how communication processes are established and their effects on marital adjustment that, again, influences the way of communicating. In a systemic perspective, this determination is irrelevant, mainly because there is an assumption of circular causality and that the feedback within a system only occurs because the parties - interlocutors - contribute to maintaining the interactional circuit (Boscolo & Bertrando, 2013; Mattelart, 2009; Watzlawick et al., 1973). Again, it is relevant to consider the complementarity in the communicational processes, although there seem to be differences, these adjust to the maintenance of marital dynamics - while gender is not relevant in this aspect, the role played by each spouse in the interactions is.

Conclusion

The communication styles investigated in this study, and the impact they have on marital adjustment were evidenced through dyadic analysis, analyzing the effect of the individuals' way of communicating about themselves and their partners. The evidence found was that the understanding of the phenomenon needs to occur from a systemic perspective especially because, in marital relationships, there are significant levels of interdependence between partners, that is, what happens with one partner tends to influence the same aspect in the other.

In research with couples, it is essential to conduct dyadic data collection that allows analyzing the influence between partners, since the phenomenon involves a pair that lives in the same context, shares interests and projects. On the other hand, collecting face-to-face data from couples involves significant time and dedication by researchers and research groups, which becomes a challenging aspect in conducting investigations of this nature. A strong point of the present study is precisely the work with dyads and the analysis carried out that allowed to assess the phenomenon in a more comprehensive perspective, considering the interaction between the partners.

On the other hand, the fact that it is a research conducted by means of self-report scales, in which the participants answer about themselves and their partners, can be considered a limitation of this study. Although there is an assumption that romantic partners know each other and, therefore, are able to infer about the perception of the spouse, experimental and longitudinal studies are an alternative to minimize this limitation left by cross-sectional studies that use self-report scales.

In addition, cross-sectional studies have other limitations, such as, for example, analysis of the sample based on a specific moment in time, since the answers are based on an assessment restricted to the recent memory of the respondents, it will consider the most recent events and experiences in the relationship. As for being a sample for convenience, it may happen that the selected people belong to an excessively homogeneous social niche - in this study, the participants were predominantly catholic with children, belonging to the middle class, and with a high educational level. Therefore, the proposed results and reflections represent, to a certain extent, a social group with such sociodemographic characteristics.

In the results of this study, the negative communication style stood out for the strength of correlations between the dyad, for the magnitude of prediction as an actor/man effect and an actor/woman effect, and mainly because in the partner/man and partner/woman effect it was the single prediction factor. These results suggest an agenda for research on romantic relationships that should pay attention to the interdependence and feedback of individual and dyadic factors, and assess whether, as observed in this study, negative issues cause more robust impacts on conjugality, thus guiding prevention and marital education programs to meet this type of demand from couples, especially regarding the maintenance of the relationship over the course of marriage.

Still, this result has relevant implications for the clinical area, as it indicates the need for couple therapists to focus their interventions on decreasing negative communication and the negativity context that is developed when communication between spouses is dysfunctional, rather than focusing on promoting positive behaviors. Furthermore, intervening in the interaction and, consequently, in the feedback mechanisms between the partners, can be the most effective method if the focus is on marital problems, since the data show that changing any of the variables will impact the partner and the relationship.

REFERENCES

Andrade, A. L., Cassepp-Borges, V., Ferrer, E., & Sanchez-Aragón, R. (2017). Análises de dados diádicos: Um exemplo a partir da pesquisa com casais. Temas em Psicologia, 25(4), 1571-1588. doi: 10.9788/TP2017.4-05 [ Links ]

Baucom, K. J. W., Baucom, B. R., & Christensen, A. (2015). Changes in dyadic communication during and after integrative and traditional behavioral couple therapy. Behavior Research and Therapy, 65, 18-28. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.004 [ Links ]

Belanger, C., Laporte, L., Sabourin, S., & Wright, J. (2015). The effect of cognitive-behavioral group marital therapy on marital happiness and problem-solving self-appraisal. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 43(2), 103-118. doi: 10.1080/01926187.2014.956614 [ Links ]

Blanchard, V. L., Hawkins, A. J., Baldwin, S. A., & Fawcett, E. B. (2009). Investigating the effects of marriage and relationship education on couples' communication skills: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(2), 203-214. doi: 10.1037/a0015211 [ Links ]

Boscolo, L., & Bertrando, P. (2013). Terapia sistêmica individual: Manual prático na clínica. Belo Horizonte: Artesã. [ Links ]

Busby, D. M., Christensen, C., Crane, D. R., & Larson, J. H. (1995). A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21(3), 289-308. doi: 10.1111/j.17520606.1995.tb00163.x [ Links ]

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., Cenci, C. B., & Mosmann, C. P. (2016). Conflitos conjugais e estratégias de resolução: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Temas em Psicologia, 24(1), 1-14, doi: 10.9788/TP2016.1-22 [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., Delatorre, M. Z., Wagner, A., & Mosmann, C. P. (2017). Terapia de casal e estratégias de resolução de conflito: Uma revisão sistemática. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 37(1), 208-223. doi: 10.1590/1982-3703000622016 [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., & Mosmann, C. P. (2015). Estratégias de resolução dos conflitos conjugais: Percepções de um grupo focal. Revista Psico, 46(4), 472-482. doi: 10.15448/1980-8623.2015.4.20606 [ Links ]

Costa, C. B., & Mosmann, C. P. (2020). Aspects of the marital relationship that characterize secure and insecure attachment in men and women. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37, e190045. doi: 10.1590/1982275202037e190045 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2010). Projeto de pesquisa: Métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Damásio, B. F. (2013). Contribuições da Análise Fatorial Confirmatória Multigrupo (AFCMG) na avaliação de invariância de instrumentos psicométricos. Psico-USF, 18(2), 211-220. [ Links ]

Deitz, S. L., Anderson, J. R., Johnson, M. D., Hardy, N. R., Zheng, F., & Liu, W. (2015). Young romance in China: Effects of family, attachment, relationship confidence, and problem solving. Personal Relationships, 22(2), 243-258. doi: 10.1111/pere.12077 [ Links ]

Delatorre, M. Z., Scheeren, P., & Wagner, A. (2017). Conflito conjugal: Evidências de validade de uma escala de resolução de conflitos em casais do sul do Brasil. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 35(1), 79-94. doi: 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.3742 [ Links ]

Delatorre, M. Z., & Wagner, A. (2018). Marital conflict management of married men and women. Psico-USF, 23(2), 229-240. doi: 10.1590/141382712018230204 [ Links ]

Driver, J., Tabares, A., Shapiro, A. F., & Gottman, J. M. (2016). Interação do casal em casamentos com altos e baixos níveis de satisfação. Estudos do Laboratório Gottman. In F. Walsh (Org.), Processos normativos da família: Diversidade e complexidade (S. M. M. Rosa, Trad., 4th ed.), (pp. 57-77). Porto Alegre: Artmed . [ Links ]

Epstein, R., Warfel, R., Johnson, J., Smith, R., & McKinney, P. (2013). Which relationship skills count most? Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 12(4), 297-313. doi: 10.1080/15332691.2013.836047 [ Links ]

Féres-Carneiro, T., & Diniz-Neto, O. (2008). Psicoterapia de casal: Modelos e perspectivas. Aletheia, 27(1), 173-187. [ Links ]

Hammett, J. F., Castañeda, D. M. & Ulloa, E. C. (2016). The association between affective and problem-solving communication and intimate partner violence among Caucasian and Mexican American couples: A dyadic approach. Journal of Family Violence, 31(2), 167-178. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9762-2 [ Links ]

Holley, S. R., Haase, C. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2013). Age‐related changes in demand‐withdraw communication behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(4), 822-836. [ Links ]

Hollist, C. S., Falceto, O. G., Ferreira, L. M., Miller, R. B., Springer, P. R., Fernandes, C. L. C., & Nunes, N. A. (2012). Portuguese translation and validation of the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38(s1), 348-358. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00296.x [ Links ]

Iveniuk, J., Waite, L. J., Laumann, E., McClintock, M. K., & Tiedt, A. D. (2014). Marital conflict in older couples: Positivity, personality, and health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(1), 130-144. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12085 [ Links ]

Johnson, M. D., Cohan, C. L., Davila, J., Lawrence, E., Rogge, R. D., Karney, B. R., ... & Bradbury, T. N. (2005). Problem-solving skills and affective expressions as predictors of change in marital satisfaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(1), 15-27. doi: 10.1037/0022006X.73.1.15 [ Links ]

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Lau, K. K. H., Tao, C., Randall, A. K., & Bodenmann, G. (2016). Coping-oriented couple therapy. In: Lebow J., Chambers A., Breunlin D. (eds). Encyclopedia of Couple and Family Therapy. Springer, Cham. [ Links ]

Luz, S. K., & Mosmann, C. P. (2018). Funcionalidade e comunicação conjugal em diferentes etapas do ciclo de vida. Revista da SPAGESP, 19(1), 21-34. [ Links ]

Markman, H. J., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., Ragan, E. P., & Whitton, S. W. (2010). The premarital communication roots of marital distress and divorce: The first five years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 289-298. doi: 10.1037/a0019481 [ Links ]

Mattelart, A. E. (2009). História das teorias da comunicação (12a ed.). São Paulo: Loyola. [ Links ]

Neumann, A. P., & Wagner, A. (2017). Reverberations of a Marital Education Program: The moderator’s perception. Paidéia, 27(1), 466-474. doi: 10.1590/1982-432727s1201712 [ Links ]

Neumann, A. P., Wagner, A., & Remor, E. (2018). Couple relationship Education Program 'Living as Partners': Evaluation of effects on marital quality and conflict. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 31(26), 1-13. doi: 10.1186/s41155-018-0106-z [ Links ]

Paleari, F. G., Regalia, C., & Fincham, F. D. (2010). Forgiveness and conflict resolution in close relationships: Within and cross partner effects. Universitas Psychologica, 9(1), 35-56. [ Links ]

Pilati, R., & Laros, J. A. (2007). Modelos de equações estruturais em psicologia: Conceitos e aplicações. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 23(2), 205-216. [ Links ]

Rech, B. C. S., Silva, I. M., & Lopes, R. C. S. (2013). Repercussões do câncer infantil sobre a relação conjugal. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 29(3), 257-265. [ Links ]

Seider, B. H., Hirschberger, G., Nelson, K. L., & Levenson, R. W. (2009). We can work it out: Age differences in relational pronouns, physiology, and behavior in marital conflict. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 604-613. doi: 10.1037/a0016950 [ Links ]

Terveer, A. M., & Wood, N. D. (2014). Dispositional optimism and marital adjustment. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 36(3), 351-362. doi: 10.1007/s10591-013-9292-0 [ Links ]

Tilden, T., Hoffart, A., Sexton, H., Finset, A., & Gude, T. (2011). The role of specific and common process variables in residential couple therapy. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 10(3), 262-278. doi: 10.1080/15332691.2011.588100 [ Links ]

Van den Troost, A., Vermulst, A., Gerris, J. R. M., & Matthijs, K. (2005). The Dutch Marital Satisfaction and Communication Questionnaire: A validation study. Psychologica Belgica, 45(3), 185-206. doi: 10.5334/pb-45-3-185 [ Links ]

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. H., & Jackson, D. D. (1973). Pragmática da comunicação humana. Um estudo dos padrões, patologias e paradoxos da interação. São Paulo: Cultrix. [ Links ]

Worthington Jr., E. L., Berry, J. W., Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Scherer, M., & Griffin, B. J., et al. (2015). Forgiveness reconciliation and communication conflict resolution interventions versus retested controls in early-married couples. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1), 14-27. doi: 10.1037/cou0000045 [ Links ]

Yaşın, F., & Sunal, A. B. (2016). The mediator role of relationship satisfaction on the relation between time perspective and responses to romantic relationship dissatisfaction. Turkish Journal of Psychology, 31(78), 91-94 [ Links ]

How to cite: Costa, C.B., & Mosmann, C.P. (2020). Negative and open marital communication: interdependent model of actor/partner effect in marital adjustment. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2283. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2283

Correspondence: Crístofer Batista da Costa. Rua Marcelo Gama, 1440/304, Auxiliadora. CEP 90540-041. Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. E-mail: cristoferbatistadacosta@gmail.com. Clarisse Pereira Mosmann. Av. Unisinos, 950 Sala 2ª109, Jardim Itu Sabará. CEP 93022000. São Leopoldo, RS, Brasil. E-mail: clarissemosmann@gmail.com

Funding: This article is part of a larger study from the doctoral thesis of the first author under the guidance of the second author and had the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, CAPES, Brazil. Financing Code 001

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. C.B.C. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; C.P.M. in a,b,c,d,e.

Received: March 27, 2019; Accepted: September 01, 2020

texto en

texto en