Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 30-Jun-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2222

Original articles

Individual well-being: the role of rumination, optimism, resilience and ability to receive support

1Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). México. rozzara@unam.mx

Subjective well-being includes having positive / negative emotional experiences, prosperity and satisfaction with life. In addition, it depends on multiple psychosocial factors such as: rumination, optimism, resilience and the ability to receive support, which have been studied in particular and need to be examined together. Therefore, this study was set out to: 1) Identify the effect of the aforementioned variables on subjective well-being in adults, and 2) Explore their differences based on gender, age and schooling. There was a voluntary participation of 404 Mexican adults aged between 18 to 64 (M=37.56), with minimum secondary schooling. The findings show the significant role of some factors of optimism, resilience and rumination in the prediction of subjective well-being as well as differences in self-confidence, (optimism), negative emotional experience (well-being), the ability to receive support between genders, and the tendency to experience more optimism, resilience and well-being as the individual gets older and schooling is higher. These results show how the positive features and life experience were associated with other kind of positive experiences for the well-being of individual.

Keywords: well-being; rumination; optimism; resilience; support

El bienestar subjetivo comprende experiencias emocionales positivas/negativas, prosperidad y satisfacción con la vida. Además, depende de múltiples factores psicosociales como: la rumia, el optimismo, la resiliencia y la capacidad para recibir apoyo, mismos que han sido estudiados en particular y necesitan ser examinados en conjunto. Por ello, este estudio se propuso: 1) identificar el efecto de las variables mencionadas en el bienestar subjetivo en adultos, y 2) explorar sus diferencias a partir del sexo, edad y escolaridad. Se contó con la participación voluntaria de 404 adultos mexicanos de entre 18 y 64 años (M=37.56), con escolaridad mínima de secundaria. Los resultados muestran el papel significativo de algunos factores del optimismo, resiliencia y rumia en la predicción del bienestar subjetivo, así como diferencias en auto-confianza (optimismo), experiencia emocional negativa (bienestar subjetivo) y capacidad de recibir apoyo entre sexos, y la tendencia a experimentar más optimismo, resiliencia y bienestar conforme se tiene más edad y escolaridad. Estos resultados muestran como los atributos positivos y la experiencia de vida se asociacian con otras experiencias positivas en pro del bienestar del individuo.

Palabras clave: bienestar; rumia; optimismo; resiliencia; apoyo

O bem-estar subjetivo abrange experiências emocionais positivas/negativas, prosperidade e satisfação com a vida. Além disso, depende de múltiplos fatores psicossociais, como: ruminação, otimismo, resiliência e capacidade de receber apoio, que foram estudados em particular e precisam ser examinados em conjunto. Para isso, este estudo se propôs a: 1) identificar o efeito das variáveis mencionadas no bem-estar subjetivo de adultos e 2) explorar suas diferenças a partir do sexo, idade e escolaridade. Contou-se com a participação voluntária de 404 adultos mexicanos entre 18 e 64 anos (M = 37,56), com escolaridade mínima de ensino médio. Os resultados mostram o papel significativo de alguns fatores de otimismo, resiliência e ruminação na predição do bem-estar subjetivo, bem como diferenças na autoconfiança (otimismo), experiência emocional negativa (bem-estar subjetivo) e capacidade de receber apoio entre os sexos, e tendência a experimentar mais otimismo, resiliência e bem-estar à medida que se tem mais idade e formação. Esses resultados mostram como os atributos positivos e a experiência de vida foram associados a outras experiências positivas para o bem-estar do indivíduo.

Palavras-chave: bem-estar; ruminação; otimismo; resiliência; apoio

Health is conceived by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2006) as a complete state of physical, spiritual, psychological and social well-being. This definition lays the foundations for the importance that the construct of psychological or subjective well-being (SW-B) (Padrós Blázquez, Gutiérrez Hernández, & Medina Calvillo, 2015) has acquired over time, and it includes −according to Naci and Loannidiss (2015) and Kaufman (2016)− the choices and activities that help achieve physical vitality, mental readiness, social satisfaction, a sense of accomplishment, and personal fulfillment.

It should be noted that the SW-B in some way represents a cultural judgment from an internal perspective or belief of the people who belong to a group about whether they live correctly, enjoy life, what others think about how each one is living is important, as well as whether individuals have a sense of fulfillment. As can be seen, this notion implies, on the one hand, the fulfillment of their basic human needs, and on the other, the ethical and evaluative judgments of people about their lives. In other words, the SW-B reflects the degree to which people live according to their evolutionary imperatives and human needs in some way, but it also represents judgments based on the norms and values which are particular to their culture (Diener, 2009).

When it comes to identifying the components of SW-B, there is a particularly outstanding model proposed by Diener (2009). This approach is one of the most comprehensive and it includes: positive and negative affection (it has to do with the emotional or affective aspects experienced by people), prosperity (which evaluates self-perceived success in areas such as relationships, self-esteem, purposes in life and optimism) and satisfaction with life (a cognitive judgment regarding the evaluation that a person makes of the quality of their life on the basis of certain criteria such as the expectations that one has about it).

This research takes the vision of Diener (2009), on the grounds that his conceptual and operational work has been more fruitful and landed from a cultural perspective of the construct in Latin America (for example, Góngora, & Castro Solano, 2015; Padrós et al., 2015). So, SW-B is built on its emotional and cognitive components, which at the same time depend on the quality of a series of specific domains such as social contact, life events, discrepancy between aspirations and achievements, perception of self-efficacy, as well as negative or positive thoughts. This can be closely linked to variables such as rumination −that reflects discomfort− (Flórez Rodríguez & Sánchez Aragón, in press), their counterparts: Optimism −that reflects well-being− and resilience (Seligman, Steen, Park & Peterson , 2005) as the ability to take advantage of the discomfort to achieve well-being, as argued below.

Rumination has been defined as the tendency to continue thinking about something bad, painful or hopeless for a long period of time (Ito, Takenaka, Tomita, & Agari, 2006). It occurs when a person repeatedly and recurrently thinks about negative events or emotions, particularly from the past (Michael, Halligan, Clark, & Ehlers, 2007). In fact, it is considered as a poorly adaptive coping strategy that perpetuates stress by increasing negative cognitions, thus deteriorating problem solving and instrumental behavior, as well as reducing social support (Eisma & Stroebe, 2017). Rumination can exist as a trait or as a state and it is defined as a damaging psychological process characterized by persistent thinking about negative content that generates emotional discomfort (R. Sansone & L. Sansone, 2012). It should be noted that, although Watkins et al. (2011) agree with the harmful side of rumination, they also recognize that this can be a beneficial psychological process since there are times when rumination is specific, concrete and focused on the process, which allows its usefulness.

There are relevant data that indicate that women have a greater tendency to ruminate than men, which contributes to experiencing greater depression, more difficulty in solving problems effectively and performing instrumental behaviors, as well as greater ability to corrode social support (Johnson & Whisman, 2013; Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994). However, it should be noted that evidence on the magnitude of the difference between the sexes in rumination has varied from study to study (Rood, Roelofs, Bogels, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schouten, 2009). In addition to these data, the literature indicates that there are contradictory pieces of information regarding the behavior of rumination when considering age. That is to say, authors such as Nolen-Hoeksema and Aldao (2011) and Sütterlin, Paap, Babic, Kübler and Vögele (2012), claim that ruminant thoughts decrease with older age because people have more cognitive and affective resources to solve problems; whereas J. Delgado Suárez, Herrera Jiménez and Y. Delgado Suárez (2008) and García Cruz, Valencia Ortiz, Hernández Martínez and Rocha Sánchez (2017), point out that as individuals become older, the recurrent ideas increase as part of the aging process, and it comes with more social isolation and fewer activities. It has been observed that the more schooling, the more diversity of rumination suppressive strategies (Delgado Suárez et al., 2008).

Regarding the relationship between rumination and SW-B, rumination has been observed to be a mediating element between stress and the ability to sleep (Berset, Elfering, Lüthy, Lüthi, & Semmer, 2011; Kompier, Taris, & Veldhoven 2012). Likewise, it has an important impact on the experience of greater psychological stress in victims of love break (Nolen-Hoeksema, McBride & Larson 1997). Other findings indicate that rumination and perceived stress have a negative relationship with the psychological well-being produced by mindfulness (e.g. Deyo, Wilson, Ong, & Koopman, 2009).

On the other hand, there are constructs such as optimism and resilience, which can be found in literature from positive psychology (Seligman et al., 2005). The first construct refers to positive expectations regarding the future −regardless of the means by which such results can occur− (Kleiman et al., 2017). It is related to greater professional success, better problem solving, good health and a longer life (Peterson, 2000). Optimism reduces pain and improves vitality (Zepeda Goncen & Sánchez Aragón, 2019). Furthermore, it contributes to greater hope, self-efficacy, motivation, confidence and perseverance in situations of great adversity or stressors (Seligman, 1991; Snyder, 1994). In agreement with this, Nolen-Hoeksema and Davis (2002), Seligman (2002) and Tashiro and Frazier (2003) argue that resilience emerges from extremely difficult and highly stressful situations, it allows to find benefits and to generate new meanings that favor both personal growth and facing new challenges with greater security and efficiency. Therefore, resilience is the human capacity to face, overcome, be strengthened or transformed by unfavorable experiences (Grotberg, 2003).

When examining the effects of gender on these variables, several claims come on the scene; Puskar et al. (2010) found that male teenagers are more optimistic than female teenagers, while in a study by Webber and Smokowski (2018) the opposite effect was observed. On other side, Schwaba, Robins, Priyanka and Bleidorn (2019) show the similarity between both sexes concerning the variable. Regarding resilience, Consedine, Magai, and Krivoshekova (2005) found that men scored higher than women did; a result supported by Coppari, Barcelata, Bagnoli and Codas (2018) but with very weak findings in just one single dimension with samples from Latin America. In Peru, the findings are in favor of women (Prado Álvarez & Águila Chávez, 2003), while in Mexico, González Arratia and Valdez Medina (2013) report that it is women who throughout their lives show more resilience compared to men.

Regarding age, Londoño Pérez, Velasco Salamanca, Alejo Castañeda, Botero Soto and Vanegas (2014) indicate that adults tend to be more optimistic than young people because they use more constructive and strategies oriented to wellness and success (Schwaba et al., 2019). Congruently, Gooding, Hust, Johnson and Tarrier (2012) indicate that adults were more resilient -particularly in the ability of emotional regulation and problem solving- than young people, while the young people showed more resilience regarding social support. And in terms of schooling, Giménez Hernández (2005) and Morales Rodríguez and Díaz Barajas (2011) reported that the more schooling, more they score in optimism and resilience (in its factors of strength, self-confidence, competence and social support) respectively. This can be explained from the fact that studying provides resources that give the person greater possibilities of being happy even at the cost of adversity. They can have more hope, a positive forecast of the future, be more cautious and deepen the analysis of the situation they face and thereby generate a better approach and solution (Gómez Azcarate et al., 2014).

Evidence shows that optimism and resilience are essential components for SW-B, since: 1) an optimistic person expects positive results even in difficult circumstances; this contributes to making people feel better, have less depression and stress and more resilience (Allison, Guichard, & Gilain, 2000); 2) this defines optimism and resilience as factors of resistance to negative emotional states, while 3) they serve as buffers for coping with difficult situations, as they provide tools in solving everyday problems, as well as viewing adversity as a challenge from which to learn and make the best of it. Therefore, both aspects have a direct impact on the SW-B itself, since this reflects the evaluation of one's resources, the optimal management of situations, which consequently affects self-esteem, self-efficacy and health (Chopik, Kim, & Smith, 2018).

But resilience as a personal resource to move forward can be combined with a high-value social resource in the individual's life: social support (Sullivan & Davila, 2010). It tends to improve psychological adjustment and health (Sarason et al., 1983), self-esteem (feeling accepted and valued), positive mood and a favorable outlook on life. Social Support predicts SW-B and it moderates the impact of stress on life (Procidano, 1992). In addition to the above, support is a protective factor that provides the psychological resources that are necessary to face stress (Chi et al., 2011) and to connect with significant others that can be of great help. However, it can be ruined if the individual himself does not have the ability to receive it (Sánchez Aragón, in press; Verhofstadt, Lemmens, & Buysse, 2013).

Thus, the objectives of this study were: 1) to identify the effect of rumination, optimism, resilience and the ability to receive support in SW-B in Mexican adults, and 2) to explore whether gender, age and schooling produce differences in the aforementioned variables.

Method

Participants

We worked with a non-probability sample (Hernández Sampieri, Fernández Collado, & Baptista Lucio, 2014) of 404 Mexican people (202 women and 202 men) aged between 18 and 64 (M= 37.56), with secondary schooling (18.6% ), high school (31.9%) and undergraduate (48%) who had a time in the relationship with their partner between 5 months and 41 years (M= 14.21 years). The reported marital status was of free union (45.8%), married (54.2%) and regarding the number of children there was a variety from 0 to 5 (Mode = 2). It should be noted that in order to meet the second objective, it was necessary to create three age groups that were equivalent in terms of the number of participants. They had to be comparable and consistent with certain stages of the life process: 17 to 30 years (group a), 31 to 44 (group b) and 45 to 62 (group c).

Measures

Sociodemographic Data Questionnaire, which is made up of some questions that allow the description of the sample, as well their classification for statistical purposes. The questions included were gender, age, schooling, relationship time, marital status and number of children.

Rumination Scale (Flórez Rodríguez & Sánchez Aragón, in press). In its short version consisting of 10 items with a five-point Likert-type answer format indicating degrees of agreement and distributed in two factors: 1) discomfort (“I give considerable thought to my suffering ”) (α=.89) and 2) obsessive reflection (“I think all the time about all my deficiencies, shortcomings, defects and errors”) (α=.84).

Optimism Scale (Sánchez Aragón, 2018). In its short version, it includes 20 items in a five-point Likert-type format that indicates degrees of agreement and. The items are organized into four factors: 1) positive attitude (“I am optimistic even though it seems that what is coming is going to be negative”) (α=.90), 2) internal control (“I think if one works hard enough, anything is possible to achieve”) (α=.78), 3) self-confidence (“No task it's too difficult for me”) (α=.81) and 4) hope (“ I think my future will be very good ”) (α=.80).

Resilience Scale (Palomar Lever & Gómez Valdez, 2010) with 25 items in Likert-type format (short version), made up of five factors: 1) strength and self-confidence (“What has happened to me in the past makes me feel confidence to face new challenges”) (α=.92), 2) social competence (“It is easy for me to establish contact with other people”) (α=.87), 3) family support (“I have a good relationship with my family ”) (α=.87), 4) social support (“I have some friends / family… who really care about me”) (α=.84) and, 5) structure (“Rules and routine make my life easier ”) (α=.79).

Support Reception Scale (Sánchez Aragón, in press) consisting of 7 Likert items (α=.79) in a single factor: “I share my feelings with other people to see if they help me”, “I let people who are close to me give me their support”, “I am willing to receive advice when I face a difficult situation”.

Subjective Well-being Scales (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985; Diener, 2009; Granillo Velasco, Sánchez Aragón, & Zepeda Goncen, 2020):

Emotional Experiences with 12 Likert items in two factors: 1) positive (“Pleasure”, “Happiness”) (α=.85) and, 2) negative (“Sadness”, “Bad”) (α=.81).

Prosperity with 8 Likert items in one factor: “I am a good person and live a good life”, “I have a useful and significant life” (α=.89).

Life satisfaction with 5 Likert items in one factor: “I am happy with my life”, “The circumstances of my life are good” (α=.84).

Procedure

The application of approximately 20 minutes was carried out by qualified psychologists who went to places where they could find people with a current relationship and with at least one month of living together (shopping malls, houses, schools, offices, recreational and cultural centers, etc.), so that they would voluntarily and anonymously answer the scales (always sorted out in the same order).They were let know that their data was confidential, that they would not cause them harm and would only be used for scientific purposes. Likewise, participants’ questions were immediately answered, and their personal results were made available to them.

Analysis of data

In order to respond to the objectives of this research, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov analysis was first performed to confirm that the variables had a normal distribution. Based on this, the decision was to perform a binary logistic regression to respond to the first objective. Later, the Mann Whitney U test and the Kruskal Wallis test were used to compare the groups. To do this, we worked with the SPSS (Statistical Program for Social Sciences) version 23.

Results

As previously mentioned, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed in order to identify if the variables are normally distributed. This condition was not met in any of the cases (p <= .041), so the choice of statistical analyzes was based on these results.

In order to answer the first objective of this research, some linear regression analyzes were initially performed to test the assumptions of error independence and non-multicollinearity of the variables. Regarding the first assumption, it was found that Durbin-Watson scores between 1 and 3 were identified for the dependent variables, which meets the independence of errors (positive emotional experience= 1.933, negative= 1.888, prosperity= 1.906 and life satisfaction= 1.822).

Regarding the second assumption, coefficients were found that indicated multicollinearity, so the decision was to carry out a second-order factor analysis and thus be able to comply with this requirement. The factor groupings were as follows: factor 1 integrated all the optimism factors, factor 2 comprised of all the resilience factors together with the ability to receive support (named from this moment “resilience +”) and finally, factor 3 was formed with the two rumination factors. Having already carried out these analyzes, the logistic regressions were carried out and the dependent variables were positive emotional experience, negative emotional experience, prosperity and life satisfaction. The predictor variables were optimism, resilience+ and rumination.

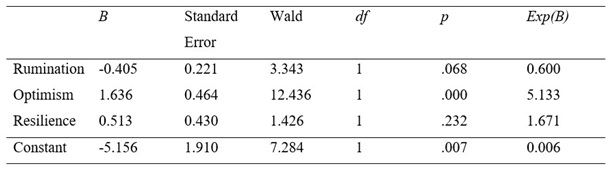

Positive Emotional Experience. For the logistic regression analysis, the zero block indicates that there is an 89% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable, assuming that most people experience high positive emotions. For block one of the model the ROA statistical efficiency score indicates that there is a significant improvement in the prediction of the probability of occurrence of the positive emotional experience (X 2=44,649; df=3; p=.000). Nagelkerke's R2 indicates that the proposed model explains 23.7% of the variance of the concerned dependent variable (0.237). However, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test indicates that the variance explained by the model explains a non-significant percentage of variance (0.522).

For the logistic regression analysis, block one indicates that there is an 89.8% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable (positive emotional experience) when rumination, optimism and resilience have been integrated into the prediction. And it is observed that as the optimism score increases, the positive emotional experience increases more. The score for the tested model indicates that the optimism variable contributes significantly to the prediction of the dependent variable (positive emotional experience). The results obtained from this model can be generalized to the sample (see Table 1).

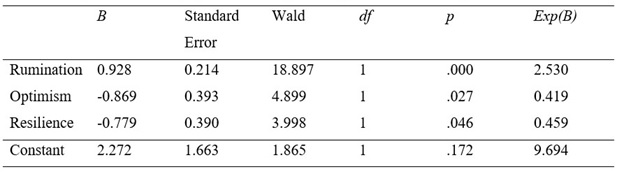

Negative Emotional Experience. For the logistic regression analysis, the zero block indicates that there is an 86% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable, assuming that most people feel high negative emotional experience. For block one of the model, the ROA statistical efficiency score indicates that there is a significant improvement in the prediction of the probability of occurrence of the negative emotional experience (X 2=56,966; df = 3; p=.000). Nagelkerke's R2 indicates that the proposed model explains 20.7% of the variance of the dependent variable under study (.207). However, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test indicates that the variance explained by the model explains a non-significant percentage of variance (0.755). For the logistic regression analysis, block one indicates that there is an 86.6% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable (negative emotional experience) when rumination, optimism and resilience have been integrated into the prediction. It is also observed that, as the rumination score increases, the probability of negative emotional experience increases and with more optimism and resilience, this probability decreases. The score for the tested model indicates that the rumination, optimism and resilience variables contribute significantly to the prediction of the dependent variable (negative emotional experience). The results obtained from this model can be generalized to the sample (see Table 2).

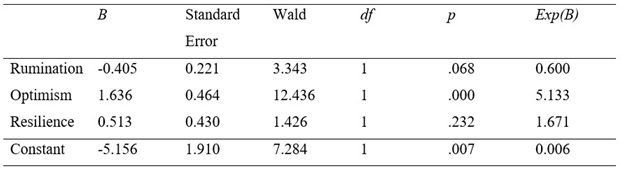

Prosperity. For the logistic regression analysis, the zero block indicates that there is a 96.6% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable, assuming that most people feel high prosperity. For block one of the model, the ROA statistical efficiency score indicates that there is a significant improvement in the prediction of the probability of occurrence of prosperity (X 2=35,386; df=3; p=.000). Nagelkerke's R2 indicates that the proposed model explains 37.0% of the variance of the prosperity variable (.370). However, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test indicates that the variance explained by the model explains a non-significant percentage of variance (0.816). For the logistic regression analysis, block one indicates that there is a 96.4% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable (prosperity) when rumination, optimism and resilience have been integrated into the prediction. And it is observed that as the rumination score increases, prosperity decreases and that, with more optimism and resilience, the probability of prosperity increases. The score for the tested model indicates that the rumination, optimism and resilience variables contribute significantly to the prediction of the dependent variable (prosperity). The results obtained from this model can be generalized to the sample (see Table 3).

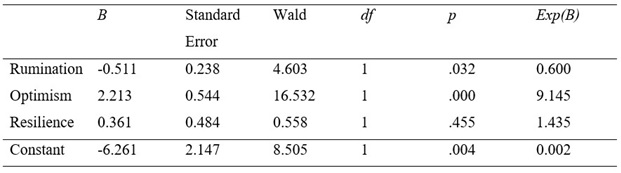

Life satisfaction. For the logistic regression analysis, the zero block indicates that there is a 90.2% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable, assuming that most people feel high life satisfaction. For block one of the model, the ROA statistical efficiency score indicates that there is a significant improvement in the prediction of the probability of occurrence of life satisfaction (X 2=56,458; df=3; p=.000). Nagelkerke's R2 indicates that the proposed model explains 30.9% of the variance of the life satisfaction variable (.309). However, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test indicates that the variance explained by the model explains a non-significant percentage of variance (0.440). For the logistic regression analysis, block one indicates that there is a 90.5% probability of correctness in the result of the dependent variable (life satisfaction) when rumination, optimism and resilience have been integrated into the prediction. And it is observed that as the rumination score increases, life satisfaction decreases and, more optimism means a greater probability of feeling more life satisfaction. The score for the tested model indicates that the rumination and optimism variables contribute significantly to the prediction of the dependent variable. The results obtained from this model can be generalized to the sample (see Table 4).

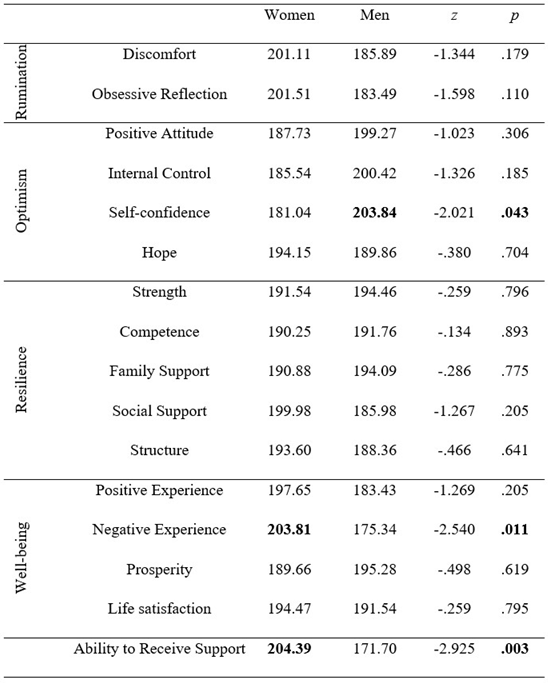

Regarding the second objective of this study, comparative analyzes were performed between groups based on gender, age, and education. For the first case, the Mann Whitney U test was performed, which indicates the supremacy of women with respect to negative experience (SW-B) and the ability to receive support, while men scored higher in self-confidence. In the other cases, no statistically significant differences were observed (see Table 5).

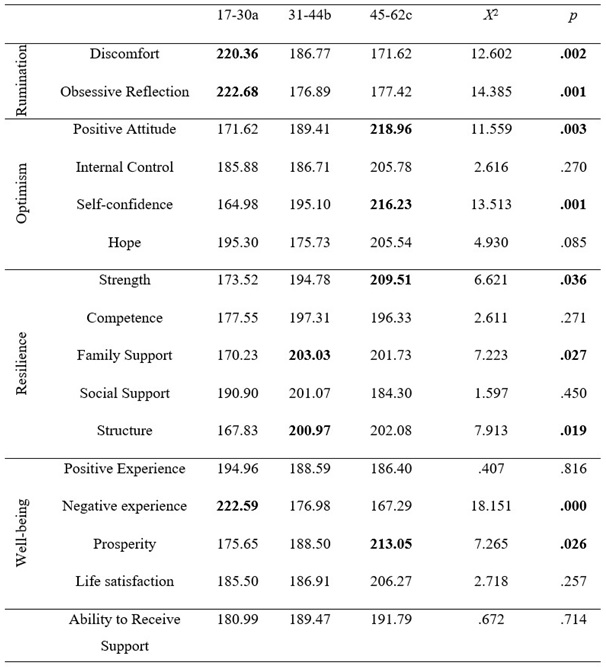

Meanwhile, to examine the differences by age and by schooling, some Kruskal Wallis tests were performed. Based on age, some statistically significant differences were identified. They show that the group of 17 to 30 years old presented more rumination and negative experience (SW-B) compared to the other groups. The group of 31 to 44 years scored more in family support and structure (resilience) compared to the younger group, while the 45 to 62-year-old group had a more positive attitude and self-confidence (optimism), strength (resilience) as well as greater prosperity compared to the younger groups (see Table 6).

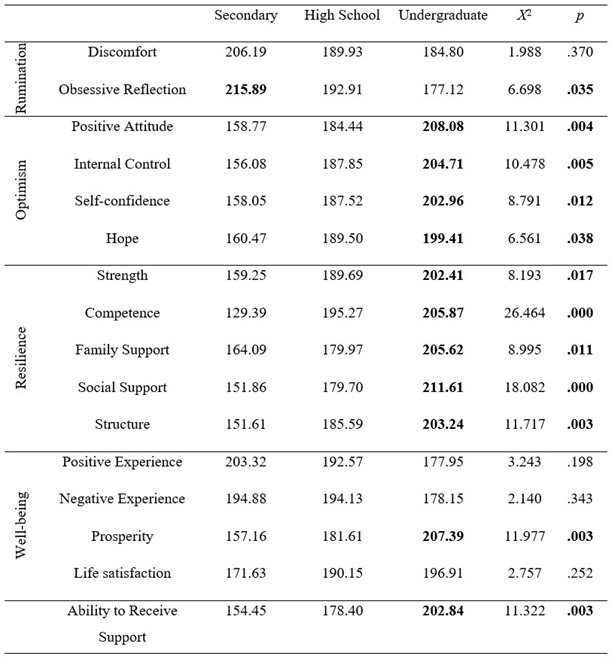

Finally, it was found that the secondary school sample scored more on obsessive reflection (rumination) compared to the undergraduates mainly. And these same participants (undergraduates) scored higher on all factors of resilience and optimism, prosperity and ability to receive support compared to those with secondary education (see Table 7).

Discussion

The objectives of this research were: 1) to identify the effect of rumination, optimism, resilience, and the ability to receive support in SW-B in Mexican adults, and 2) to explore whether gender, age, and schooling produce differences in the aforementioned variables.

To fulfill the first objective, some logistic regression analyzes were carried out that required the performance of a factor analysis of principal components (PCA) which unified the factors of each of the predictor variables (rumination, optimism and resilience) and added the ability to receive support the last one. These analyzes made it possible to identify -from the aforementioned predictors- the probability of occurrence of each of the components of the subjective well-being model proposed by Diener (2009) which is extensively studied around the world. Thus, it was observed that the high positive emotional experience (such as pleasure, happiness or joy) in the participants is due to the contribution of optimism. This may be because satisfactory feelings −such as those mentioned above− are more feasible when there is a more positive disposition towards future events. It is considered that from their own actions, an individual can be well, feel self-confidence and hope of what can happen in the immediate and mediate (Seligman, 1991; Snyder, 1994). In agreement with this, in order to be able to predict an increase in the occurrence of the experience of negative emotions (such as fear, displeasure or sadness) an increase in rumination is necessary, as well as a decrease in optimism, resilience and the ability to receive support for. This can occur since both discomfort and obsessive reflection that one experiences, generates emotional malaise (R. Sansone & L. Sansone, 2012) that harms the person. In addition to this, being pessimistic and consequently having thoughts and emotions around disgust, annoyance, grief and suffering from the past, permeates the daily life, perpetuating stress and low psychosocial performance. This significantly undermines the necessary ability to move forward and the social support (Eisma & Stroebe, 2017), which contradicts Watkins et al. (2011) when he points out that rumination has a positive edge, which should be examined more carefully.

On the other hand, positive attitude, internal control, self-confidence and hope (optimism), predict the probability of a feeling of high prosperity in the participants. According to Diener (2009), prosperity is a feeling of personal success, of their personal relationships and purposes in life, which nurtures and is nurtured by other personal attributes that facilitate and direct life −such as optimism− and providing well-being psychological.

Life satisfaction can occur −according to the findings of this research− when there is a decrease in rumination, that is, obsessive thoughts that generate discomfort and an increase in optimism (e.g. being positive even though it seems that what is coming will be negative, believing that if you work hard enough you can achieve anything, believing that no task is too difficult and that the future is promising). This is evident since the global judgment of well-being lies in the evaluation that a person makes of the quality of life by virtue of certain criteria such as his expectations. Optimism is represented precisely by the hope that what comes next is surmountable and positive no matter what needs to be done (Kleiman et al., 2017), which automatically explains the role of rumination.

Regarding the second objective, the data shows that in terms of rumination, resilience, positive emotional experience, prosperity and life satisfaction, similarities were observed rather than differences. That is, both men and women tend to have −in equal measure− repetitive and recurrent thoughts about negative emotions experienced in the past (Ito et al., 2006; Michael et al., 2007) they tend to show ability to cope, overcome, be strengthened or transformed by unfavorable experiences (Grotberg, 2003), and have emotional experiences such as joy and happiness as well as feeling successful in life and feeling that their lives have been good. However, some statistically significant differences were observed, indicating that women showed a greater negative experience in the last month and more capacity to receive support; while men showed more self-confidence (optimism factor). This could be due to the fact that it is women who have been identified as more emotionally sensitive, encompassing negative emotions. That is, since they have developed more skills in this field, their experiences and expressions are more intense and expressive (e.g. Feldman-Barret, Lane, Sechrest, & Schwartz, 2000; López Usero, 2016). In addition to this, it has been observed that it is women who tend to establish closer personal relationships (Juárez Ramírez, Valdez Santiago, & Hernández Rosete, 2005) where they tend to share more of their lives and emotions, thus evidencing their willingness to receive help, advice, etc. (Matud, Ibañez, Bethencourt, Marrero, & Carballeira, 2003; Pettus-Davis, Veeh, Davis, & Tripodi, 2018).

When the possible differences in rumination, optimism, resilience, SW-B and ability for support by age were examined, some statistically significant differences were found that show that the group of 17 to 30 years presents more rumination and negative experience (SW-B) compared to older groups. This could be because in youth, people tend to appreciate life in such a way that they feel the discomfort of their mistakes or emotions from the past that may have been generated by inexperience, unlike the older groups who can find the positive in the little ones. details of life (Reig, 2000). These results are consistent with what was indicated by Nolen-Hoeksema and Aldao (2011) and Sütterlin et al. (2012) who explain the phenomenon based on the idea that, as the years go by, people acquire more cognitive and affective resources to solve problems. Likewise, it was observed that the group of 31 to 44 years scored more in “family support” and “structure” compared to the younger group, which is logical −and related to the previous result− since as one gets older, more organization and order in life is acquired. This allows to keep busy and makes the situation more manageable in times of stress. This, together with the support networks that emerge through time, provide individuals with protection in times of need (Jiang, Drolet, & Kim, 2018). Lastly, the 45 to 62-year-old group has a more positive attitude, self-confidence and strength, as well as greater prosperity compared to the younger ones, which is supported by Londoño et al. (2014) and Schawaba et al. (2019) who claim that the older they are, the more optimistic they are; the more they value relationships with others, the more constructive and wellness-oriented strategies they count on, which allows them to obtain more achievements in different spheres of life. This brings about a feeling of a more prosperous and successful life.

Finally, there were two main findings when exploring possible differences in the variables under study by schooling. On the one hand, it was found that the secondary school sample scored more in obsessive reflection mainly compared to the undergraduates, which may be due to the fact that less education means being less able to suppress this type of thinking (Delgado Suárez et al., 2008), especially because they have probably experienced more difficult challenges to solve due to lack of experience and abilities. And, on the other hand, there is also the fact that those with undergraduate studies scored higher in all factors of optimism and resilience, prosperity and ability to receive support compared to those with secondary education. This is no surprise if we take into consideration that through education, studying provides resources that give the person greater possibilities of being happy even in spite of adversity. They can have more hope, a positive forecast of the future, be more cautious and deepen the analysis of the situation they face and thereby generate a better approach and solution (Giménez Hernández, 2005; Gómez Azcarate et al., 2014; Morales Rodríguez & Díaz Barajas, 2011). In the same way, more personal relationships are developed that sensitize the person so that he or she can reckon the need for others. All this together, leads to the idea that these resources provided by education provide both material and psychological prosperity (Carmona Valdés, 2009; García & Hoffman, 2002).

In conclusion, it can be said that SW-B is the product of some aspects mainly linked to optimism and ruminant thinking. In addition, age and schooling -more than gender- significantly affect the experience of these variables, which should be taken into account for future research. It is considered that this study managed to scrutinize the relationship as well as differences in the behavior of these variables from a broader angle and in a sample of 404 participants, resulting in a contribution to the understanding of them, of the constructs and this group.

Acknowledgements:

To the General Directorate of Support for Academic Staff of the National Autonomous University of Mexico for financing the project: PAPIIT IN304919 “Protective factors and risk to health in healthy couples with chronic degenerative disease”.

REFERENCES

Allison P. J., Guichard C. & Gilain L. (2000). A prospective investigation of dispositional optimism as a predictor of health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 9(8) 951-60. doi: 10.1023/A:1008931906253 [ Links ]

Berset, M., Elfering, A., Lüthy, S., Lüthi, S., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). Work stressors and impaired sleep: rumination as a mediator. Stress & Health, 27(2), 71-82. doi: 10.1002/smi.1337 [ Links ]

Carmona Valdés, S. E. (2009). El bienestar personal en el envejecimiento. Revista de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Iberoamericana, IV(7), 48-65. [ Links ]

Chi, P., Tsang, S. K. M., Chan, K. S., Xiang, X., Yip, P. S. F., Cheung, Y. T., & Zhang, X. (2011). Marital satisfaction of Chinese under stress: Moderating effects of personal control and social support. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 14, 15-25. doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2458-13-1150 [ Links ]

Chopik, W. J., Kim, E. S., & Smith, J. (2018). An examination of dyadic changes in optimism and physical health over time. Health Psychology, 37(1), 42-50. doi: 10.1037 / hea0000549 [ Links ]

Consedine, N. S., Magai, C., & Krivoshekova, Y. S. (2005). Socioemotional functioning in older adults and their links to physical resilience. Ageing International, 30(3), 209-244. doi: 10.1007/s12126-005-1013-z [ Links ]

Coppari, N., Barcelata, B. E., Bagnoli, L., & Codas, G. (2018). Efectos de la edad, el sexo y el contexto cultural en la disposición resiliente de los adolescentes de Paraguay y México. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 5(1), 16-22. doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2018.05.1.2 [ Links ]

Delgado Suárez, J., Herrera Jiménez, L., & Delgado Suárez, Y. (2008). La mediatización del pensamiento rumiativo en el accidente cerebrovascular. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, 5(1), 15-23. [ Links ]

Deyo, M., Wilson, K. A., Ong, J. & Koopman, C. (2009). Mindfulness and rumination: does mindfulness training lead to reductions in the ruminative thinking associated with depression? Explore, 5(5), 265-271. [ Links ]

Diener, E. (2009). Culture and Well-being Works of Ed Diener. En E. Diener (Ed.), Culture and Well-being: The Collected Works (pp. 1-8). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [ Links ]

Eisma, M. C. & Stroebe, M. S. (2017). Rumination following bereavement: an overview. Bereavement Care, 36(2), 58-64. doi: 10.1080/02682621.2017.1349291 [ Links ]

Feldman-Barret, L., Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Schwartz, G. E. (2000). Sex differences in emotional awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1027-1035. doi: 10.1177/01461672002611001 [ Links ]

Flórez Rodríguez, Y. N. & Sánchez Aragón, R. (en prensa). Evaluando el amor compasivo en la pareja. Salud y Administración. [ Links ]

García, P. S. & Hoffman, S. T. (2002). El Bienesar como preferencia y las mediciones de pobreza. Cinta Moebio, 13, 70-73. [ Links ]

García Cruz, R., Valencia Ortiz, A. I., Hernández Martínez, A., & Rocha Sánchez, T. E. (2017). Pensamiento rumiativo y depresión entre estudiantes universitarios: repesando el impacto del género. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 406-416. [ Links ]

Giménez Hernández, M. (2005). Optimismo y pesimismo: variables asociadas en el contexto escolar. Pulso, 28, 9-23. [ Links ]

Gómez Azcarate, E., Vera, A., Ávila, M. E., Musitu, G., Vega, E., & Dorantes, G. (2014). Resiliencia y felicidad en adolescentes frente a la marginación urbana en México. Psicodebate, 14(1), 45-68. doi: 10.18682/pd.v14i1.334 [ Links ]

Góngora, V. C., & Castro Solano, A. (2015). La validación de un índice de bienestar para población adolescente y adulta de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. PSIENCIA. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencia Psicológica, 7, 329-338. doi: 10.5872/psiencia/7.2.21 [ Links ]

González Arratia López Fuentes, N. I. & Valdez Medina, J. L. (2013). Resiliencia: diferencias por edad en hombres y mujeres mexicanos. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 3(1), 941-955. doi: 10.1016/S2007-4719(13)70944-X [ Links ]

Gooding, P. A., Hurst, A., Johnson, J., & Tarrier, N. (2012). Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 22-270. doi: 10.1002 / gps.2712 [ Links ]

Granillo Velasco, A. D., Sánchez Aragón, R. & Zepeda Goncen, G. D. (2020, julio). Bienestar Subjetivo: Medición integral y Validación en México. Revista Duanzary. En proceso de evaluación. [ Links ]

Grotberg, E. H. (2003). Resilience for Today: Gaining Strength from Adversity. Greenwood, SC: Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, P. (2014). Metodología de la investigación. México: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Ito, T., Takenaka, K., Tomita, T., & Agari, I. (2006). Comparison of ruminative responses with negative rumination as a vulnerability factor for depression. Psychological Reports, 99, 763-772. doi: 10.2466/PR0.99.7.763-772 [ Links ]

Jiang, l., Drolet, A., & Kim, H. S. (2018). Age and support seeking: understanding the role of perceived social costs to others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 44(7), 1104-1116. doi: 10.1177/0146167218760798 [ Links ]

Johnson, D. P. & Whisman, M. A. (2013). Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4), 367-374. doi: 10.1016 / j.paid.2013.03.019 [ Links ]

Juárez Ramírez, C., Valdez Santiago, R. & Hernández Rosete, D. (2005). La percepción de apyo social en mujeres con experiencia de violencia conyugal. Salud Mental, 28(4), 66-73. [ Links ]

Kaufman, S. B. (2016). The Differences between Happiness and Meaning in Life. Scientific American Blog Network. Descargado el 3 de Agosto, 2019 de: Descargado el 3 de Agosto, 2019 de: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautiful-minds/the-differences-between-happiness-and-meaning-in-life/ [ Links ]

Kleiman, E. M. Chiara, A. M., Liu, R. T., Jager-Hyman, S. G., Choi, J. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2017). Optimism and well-being: a prospective multi-method and multidimensional examination of optimism as a resilience factor following the occurrence of stressful life events. Journal Cognition and Emotion, 31(2), 269-283. doi: 10.1080 / 02699931.2015.1108284 [ Links ]

Kompier, M. A. J., Taris, T. W., & Veldhoven, M. V. (2012). Tossing and turning-insomnia in relation to occupational stress, rumination, fatigue and well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 38(3), 238-246. doi: 10.5271 / sjweh.3263 [ Links ]

Londoño Pérez, C., Velasco Salamanca, M., Alejo Castañeda, I., Botero Soto, P., & Vanegas, I. (2014). What makes us optimistic? Psychosocial factors as predictors of dispositional optimism in young people. Terapia Psicológica, 32(2), 153-164. [ Links ]

López Usero, S. (2016). Regulación emocional y género: un estudio exploratorio con estudiantado de grados feminizados. Tesis de grado. Descargada el 10 de agosto del 2019: Descargada el 10 de agosto del 2019: http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/handle/10234/161877 [ Links ]

Matud, M. P., Ibañez, I., Bethencourt, J. M., Marrero, R., & Carballeira, M. (2003). Structural gender differences in perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences , 35(8), 1919-1929. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00041-2 [ Links ]

Michael, T., Halligan, S. L., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (2007). Rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression & Anxiety, 24(5), 307-317. doi: 10.1002 / da.20228 [ Links ]

Morales Rodríguez, M. & Díaz Barajas, D. (2011). Estudio comparativo de la resiliencia en adolescentes: el papel del género, la escolaridad y la procedencia. Revista de Psicología Uaricha, 8(17), 62-77. [ Links ]

Naci, H. & Loannidis, J. P. A. (2015). Evaluation of Wellness Determinants and Interventions by Citizen Scientists. JAMA, 314(2), 121-122. doi: 10.1001 / jama.2015.6160 [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Aldao, A. (2011). Gender and age differences in emotion regulation and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences , 51, 704-708. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.012 [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Davis, C. G. (2002). Positive responses to loss: Perceiving benefits and growth. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 598-606). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1061-1072. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1061 [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., McBride, A., & Larson, J. (1997). Rumination and psychological distress among bereaved partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 72(4), 855-862. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.4.855 [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L.E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 67, 92-104. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.1.92 [ Links ]

Organización Mundial de la Salud (2006). Constitución de la Organización Mundial de la Salud. Documentos Básicos: Suplemento 45ta. ed.. Recuperado el 10 de agosto de 2019 de: Recuperado el 10 de agosto de 2019 de: http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_sp.pdf [ Links ]

Padrós Blázquez, F., Gutiérrez Hernández, C. Y. & Medina Calvillo, M. A. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la vida (SWLS) de Diener en población de Michoacán (México). Avances de Psicología Latinoamericana, 33(2), 223-232. doi: 10.12804/apl33.02.2015.04 [ Links ]

Palomar Lever, J. & Gómez Valdez, N. E. (2010). Desarrollo de una escala de medición de la resiliencia con mexicanos (RESI-M). Interdisciplinaria, 27(1), 7-22. [ Links ]

Peterson, C. (2000). The future of optimism. American Psychologist, 55(1), 44-55. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.44 [ Links ]

Pettus-Davis, C., Veeh, C. A., Davis, M., & Tripodi, S. (2018). Gender differences in experiences of social support among men and women releasing from prison. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(9), 1161-1182. doi: 10.1177/0265407517705492 [ Links ]

Prado Álvarez, R. & del Águila Chávez, M. (2003). Diferencia en la resiliencia según género y nivel socioeconómico en adolescentes. Persona, 6, 179-196. [ Links ]

Procidano, M. E. (1992). The nature of perceived social support: Findings of meta-analytic studies. En C. D. Spielberger & J. N. Butler (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 9, pp. 1-26). Hilsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Puskar, K. R., Bernardo, L. M., Ren, D., Haley, T. M., Tark, K. G., Switala, J., & Siemon, L. (2010). Self-esteem and optimism in rural youth: Gender differences. Contemporary Nurse, 34(2), 190-198. doi: 10.5172 / conu.2010.34.2.190 [ Links ]

Reig, A. (2000). La calidad de vida en gerontología como constructo psicológico. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 35(S2), 5-16. [ Links ]

Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bogels, S.M., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schouten, E. (2009). The influence of emotion-focused rumination and distraction on depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 607-616. doi: 10.1016 / j.cpr.2009.07.001 [ Links ]

Sánchez Aragón, R. (2018). El Inicio y el Final de la Pareja: Variaciones en Admiración, Optimismo y Pasión Romántica. En R. Díaz Loving, L. I. Reyes Lagunes & F. López Rosales (Eds.). La Psicología Social en México, Vol. XVII (pp. 999-1016). Monterrey: Asociación Mexicana de Psicología Social. [ Links ]

Sánchez Aragón, R. (en prensa). Apoyo de la pareja: Satisfacción, Capacidad para Recbirlo y Resiliencia en México. Revista Costarricense de Psicología. [ Links ]

Sansone, R. A. & Sansone, L. A. (2012). Rumination: relationships with physical health. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 9(2), 29-34. [ Links ]

Sarason, I. G., Levine, H. M., Basham, R. B., & Sarason, B. R. (1983). Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire. Journal of Persona lity and Social Psychology , 44(1), 127-139. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.127 [ Links ]

Schwaba, T., Robins, R. W., Priyanka, H. S., & Bleidorn, W. (2019). Optimism development across adulthood and associations with positive and negative life events. Social Psychological and Personality Sciences, 1-10. doi: 10.1177/1948550619832023 [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist , 60, 410 - 421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410 [ Links ]

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The psychology of hope: You can get here from here. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Sullivan, K. & Davila, J. (2010). Introduction. En K. Sullivan & J. Davila (Eds.). Support processes in intimate relationships (pp. xix-xxix). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sütterlin, S., Paap, M.C.S., Babic, S., Kübler, A. & Vögele, C. (2012). Rumination and age: some things get better. Journal of Aging Research, 1-10. doi: 10.1155 / 2012/267327 [ Links ]

Tashiro, T., & Frazier, P. (2003). "I'll never be in a relationship like that again": Persona l growth following romantic relationship breakups. Personal Relationships, 10(1), 113-128. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00039 [ Links ]

Verhofstadt, L. L. L., Lemmens, G. M. D., & Buysse, A. (2013). Support‐seeking, support‐provision and support‐perception in distressed married couples: A multi‐method analysis.Journal of Family Therapy, 35(3), 320-339. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.12001 [ Links ]

Watkins, E.R., Mullan, E., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Steiner, H., Bathurst, N., Eastman, R., & Scott, J. (2011). Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for residual depression: phase II randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(4), 317-322. doi: 10.1192 / bjp.bp.110.090282 [ Links ]

Webber, K. C. & Smokowski, P. R. (2018). Assessment of adolescent optimism: measurement invariance across gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of Adolescence, 68, 78-86. doi: 10.1016 / j.adolescence.2018.06.014 [ Links ]

Zepeda Goncen, G. D. & Sánchez Aragón, R. (2019). Efectos del Apego, Afecto y Capacidad de Recibir Apoyo en la Salud de la Pareja. Revista Psicologìa e Eduçao (On-Line ), 2(1), 66-76. [ Links ]

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. R. S. A has contributed in a,b,c,d,e.

Correspondence: Rozzana Sánchez-Aragón. Av. Universidad 3004, Col. Copilco-Universidad, C.P. 04510 Del. Coyoacán, Ciudad de México, México. E-mail: rozzara@unam.mx

How to cite: Sánchez-Aragón, R. (2020). Individual well-being: the role of rumination, optimism, resilience and ability to receive support. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2222. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2222

Received: August 14, 2019; Accepted: June 30, 2020

texto em

texto em