Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 19-Mayo-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2210

Original articles

Labor trajectories of women from popular sector in transition to adult life

1 Universidad Católica de Córdoba. Argentina griseldacardozo656@hotmail.com, anasilviagonza@hotmail.com

This work refers to a qualitative study whose propose is to characterize the labor trajectories of young women from popular sectors of Cordoba (Argentina) in their transition to adult life, setting the vulnerability factors that characterize them. We have worked with ten women between the ages of 20 and 26, who were attending two socio labor educational centers, and we have used their biographical stories as an instrument of data collection. The core categories identified as biographical axes related to the role of labor experience were: The inherited socio economic conditions, the gender conditions, the pathways towards the transition education-work and the incidence of labor qualifications in the construction of the future. The results have shown diversity in their insertion to the adult world, setting the equation of being young, women and poor as a barrier which delineates the options and necessities as well as the aspirations and obstacles which arise.

Keywords: woman; young; popular sector; transition to adult life; labor trajectory

El presente refiere a un estudio cualitativo que se propuso caracterizar las trayectorias laborales de mujeres jóvenes de sectores populares de Córdoba (Argentina) en su transición a la vida adulta, indicando los factores de vulnerabilidad que las caracterizan. Se trabajó con diez mujeres entre 20 y 26 años que concurrían a dos centros educativos socio laborales y se utilizó como instrumento de recolección de datos el relato biográfico. Las categorías centrales identificadas como ejes biográficos vinculados al papel de la experiencia laboral fueron: Las condiciones socioeconómicas heredadas, las condiciones de género, los itinerarios entorno a la transición educación - trabajo, la incidencia de la capacitación laboral en la construcción del futuro. Los resultados mostraron diversidad en su inserción al mundo adulto, siendo la ecuación de ser jóvenes, mujeres y pobres una barrera que delimita tanto las opciones y necesidades, como las aspiraciones y obstáculos que se presentan.

Palabras clave: mujer; joven; sector popular; transición a la vida adulta; trayectoria laboral

O presente estudo refere-se a uma investigação qualitativa que teve como objetivo caracterizar a trajetória de carreira de jovens de setores populares de Córdoba (Argentina) em sua transição para a vida adulta, indicando os fatores de vulnerabilidade que as caracterizam. Trabalhamos com dez mulheres entre 20 e 26 anos que frequentaram dois centros educacionais sócio laborais e utilizamos o relato biográfico como instrumento de coleta de dados. As categorias centrais identificadas como eixos biográficos vinculadas ao papel da experiência de trabalho foram: condições socioeconômicas herdadas, condições de gênero, itinerários em torno da transição educação-trabalho, incidência da formação profissional na construção do futuro. Os resultados mostraram diversidade na inserção no mundo adulto, sendo a equação de ser jovem, mulher e pobre uma barreira que delimita tanto opções e necessidades, como aspirações e obstáculos que surgem.

Palabras-chave: mulher; jovem; setor popular; transição para a vida adulta; carreira

Introduction

The process of transition of the young people into adult life has become a theme subject to investigation and discussion in psychology and in related fields of knowledge. Thus, we may find diverse conceptualizations according to the socio historical context and the prevailing theories.

In this framework, from the sociology transition point of view, we analyze this path as a process of emancipation which implies familiar as well as economic aspects (Casal, García, Merino, & Quesada, 2006; Furlong & Cartmel, 1997). Thereby, it is shown in the sixties that the majority of the young people entered the adult world through trajectories connected with the reproduction of modern institutions such as the school ticket, the acquisition of a job and the building of a family (Arnett, 2015). From a critical view, Roberti (2017a) sustains that, according to this approach, the idea of transition is associated with a “lineal, teleological and static vision of the youth” (page 492) in which the risk is not to be able to identify the different modalities of this path related to the historical moment and the heterogeneity typical of the juvenile condition.

Currently, the life of the young people that goes between the ages of 18 and 29 is completely different. The modifications that took place in the social structure specially in Latin America due to the impact caused by the economic and social transformations connected with the crisis of the Well-being States (Castel, 2012), open a different pathway in relation to the entrance to adult life. In this context, the notion of career and lineal trajectories loses its validity (Machado Pais, 2007) associated with a straight and clearly delineated path to the work life of the subjects, possible of prediction and upward mobility. On the contrary, the insertion is built from processes that are extended in time and characterized by the alternation of unemployment periods, precarious jobs, setting labor trajectories each time less predictable (Millenaar, 2014a).

In this respect, the strong impact of these socio demographic changes, specially for the juvenile sector, has also been registered in Argentina. The process of the work market dismantle beginning in the 70s and its deepening in the years 2001-2002, had an impact on the unemployment levels, labor flexibility, the fall of the real salary and the decay of the labor conditions (Benza, 2012). This has deepened even more the gaps, being the young people of poor and exclusion sectors the most affected ones.

In these sceneries, the investigations show that the deprivations increase and have an impact on their biographies (Aisenson et al., 2015; ODSA, 2018). At the same time, to include the perspective of gender in this area makes us wonder about the additional difficulties connected with the fact of being woman in their labor trajectories. In spite of the advances in the social policies regarding the incorporation of gender approaches in the last years, it is observed that major inequalities in the work market still prevail (Micha & Pereyra, 2019).

Young women continue in clear disadvantages in spite of the advances related to the incorporation of gender approaches in the public policies, that is why they continue facing discrimination in their processes of insertion as well as in the possibility of building professional carriers (Millenair & Jacinto, 2015).

In addition, it is proved that the growing access of the young women to secondary education and the attainment of the corresponding certification when finishing the studies are not enough to modify the traditional gender mandates. Therefore, they continue to be included in activities that are part of unpaid work (inside the house), thus limiting their labor participation and perpetuating gender inequality (Arancibia & Miranda, 2017; Bukstein, 2019). For this reason, their occupations are associated with the sector of services (education, health, housework, commercial activities, among others), and the gap becomes more evident in jobs oriented to hierarchy positions (Rodriguez Enriquez & Marzonetto, 2016).

In this regard, although the female labor participation was incremented in the last decades, it was not possible to advance either in the reduction of their segregation in the work market or in the salaries that continue to be unfavorable for the women. In the province of Cordoba (Argentina), apart from some initiatives of the State for the young people, the socio economic indicators for the population aged between 14 and 29 years old belonging to Gran Cordoba (Cordoba and its surrounding areas) show a significant contrast between men and women: whereas the rate of activity for the men is of 59.9%, that of the women is of 47.4%. Likewise, the employment rate for the women is of 37.4% compared to the 51.7% for the men (INDEC, 2019). Moreover, the differences outstand when analyzing the young people who neither study nor work: for the first quarter of 2018 this group is composed of the total of 50% of the young people (31% women who neither study nor work compared to 19% of the men). And when considering the level of home incomes per capita, we may observe that this 19% of men is concentrated in the poorest homes as regards their incomes per capita (45% in the first quintile and 26% in the second quintile). However, among the women this concentration in poor homes is even more stressed: the 84% of the young women who neither study nor work comes from those homes (54% of the first quintile and 30% of the second quintile) (DIIE, 2018).

In consequence, the results herein considered reflect the hypothesis of the “feminization” of poverty. Precisely, at the beginning of their fertile age, the women have a different behavior according to the home income level. On the one hand, it is probable that the early maternity of the women from poor homes may partly explain the school dropouts and their inactive status in the labor market. So, both factors have a negative incidence in their possibilities to improve the home incomes, which in turn reinforces the poverty condition. On the other hand, the women from homes with middle and high incomes not only postpone their maternity but also have access -in a higher proportion- to superior educational levels and consequently to better incomes in their labor life. This data explains the fact that young women be a vulnerable social group exposed to a major degree than others to the risk of social exclusion and poverty (Gontero & Weller, 2015).

Facing this reality, there appears the necessity to investigate in our area the labor trajectories - understanding them as those itineraries of different positions delineated by the subjects throughout their life (Roberti, 2017b) - taking into account the gender and social class conditions. To this end, we have proposed to present reflections and results of an investigation in which it is analyzed the labor trajectories in transition to adulthood in young women of the City of Cordoba (Argentina), aged between 20 and 26 years old who belong to popular sectors. For this reason, we have explored their changes and continuities as well as the vulnerability factors that characterize them.

The biographic perspective provides a valuable contribution to the study. Since starting from the reconstruction and analysis of the labor trajectories, it is feasible to elucidate the perceptions and meanings built by this age group in relationship with their paths through the labor market - without disregarding the context in which the individual trajectory develops (Roberti, 2017b) - incorporating the notion of temporality in the analysis of these processes.

Method

Design

The investigation process was carried out from a qualitative approach and adopted an exploratory design. It focused on the stories of the young women, that is why it did not look for constructing typologies but generating a dialog process in which the expressions of the subject are stressed (Gonzalez Rey, 2008).

Participants

Two institutions were selected: a Socio Educational and Labor Center with governmental dependence that articulates actions with the Education Ministry and with the Agency of Employment Promotion and Professional Training. The objective of this Center is to ensure the young people the access to education and professional training in order to generate opportunities for social inclusion. In this space the young may access different modalities to finish their formal studies, and a Center that belongs to a religious community where there is a labor training school. It is part of a social program destined to the young people with high indexes of poverty and unemployment who look for a qualification with official certification to continue with their jobs.

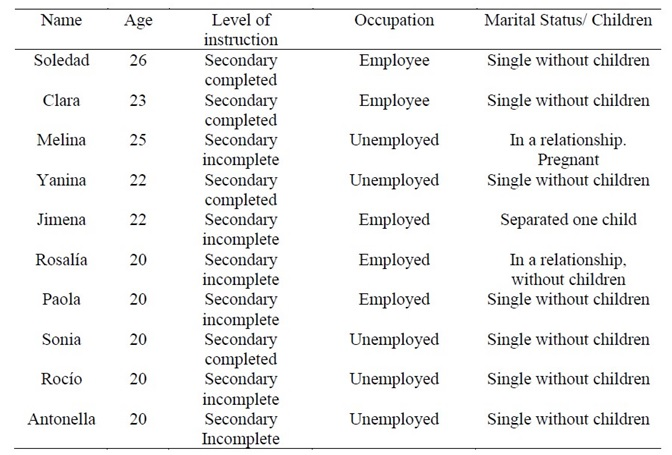

The conformed sample was intentional with cases containing rich information to provide an in depth study (Patton, 1990). The criteria implemented allowed to conform an intensive type sample due to the quality of the information obtained -characterized by the viability and accessibility- as well as being representative of the phenomena under study (being no more than 29 years old, residing in neighborhoods from popular sectors). We have worked with ten women aged between 20 and 26 who were attending both institutions during the period that lasted the collection of data (first semester of 2018). Chart 1 shows information about socio demographic data.

We have taken into account ethic measures in the realization of the work (Cornejo, Mendoza & Rojas, 2008), we have requested the authorization of the institutions to make the interviews. We have read and given the young women so as to sign an Informed Consent in which it was explained the institutional frame, the main objectives of the investigation, the voluntary character of the participation, the opportunity to discontinue the study when considering so, the anonymous and confidential conditions when handling the collected data. Any testimony that may identify them has been modified.

Instrument

The methodological strategy used in the preparation of the empirical data was the biographic story (Leclerc-Olive, 2009), since it allows the narrative display of the vital experiences of the subject throughout time. At this point, the idea of trajectory is related to the pathway and not to a lineal vision of time in the course of life (Casal, et al., 2006).

Procedure

The building of the stories was carried out through five in depth interviews, which were unrecorded and transcribed to be worked upon in each meeting with the young women. In this way, we arrived at the construction of their biographies in a process during which they put in temporally order he events that delineated their vital itineraries.

Data Analysis

For the treatment of the data, we followed the strategy of constant comparison of the theory based upon which it was built and codified the corpus of interviews and stories simultaneously. Software AtlasTi Version 7.5.4 was used as assistant. Concerning the building of the labor trajectories that lead the pathway of transition towards the adulthood of the young women, we have identified the events and significances embodied in the set of stories and interviews. In order not to overpass the maximum extension of the article, we have presented in a general way the propositions built around the central category, including fragments of the stories as illustration

Results

Beginning of early labor trajectories and inherited socio-economic conditions

From the stories of the young women, it was possible to detect that the characteristics of their labor insertion are connected with the concerns revealed from the factors that derive from their social origin, being their exclusion experiences the major obstacles for them and a difficult condition to change in the future. As shown in the studies carried out, the families give to the young men and women from popular sectors the first contacts with the labor world, although this is usually precarious and close to the place of residence (Deleo, 2017).

In this context, an element that determines the early labor insertion of the young women is the economic instability of their homes (salary cuts, nonregistered jobs, losses of employment, etc.). This socio-economic fragility triggers the early insertion of one or more of the children, adding the issue of not finishing their studies, and consequently, it is observed even more frequently the acquisition of precarious and low paid jobs since adolescence.

I worked when I was younger, at 9 I started to sweep sidewalks, they paid me for that, but my mother kept the money. Also, when I was 9 or 10 years old, I took care of my grandfather’s children and I got paid for that, and I gave the money to my mother (Jimena’ s life story, 2017).

I started to work specially because my father, who worked in a car factory, was laid off last year because of a problem, they were cancelling the contracts and all that stuff, so they fired him, an injustice and everything was wrong. I worked in different places, at a hamburger place, for example (Yanina’s life story, 2018).

On the other hand, we find that the changes in the family structure and dynamics, a result from a lot of events related to violence and addictions, makes the daughters be in charge of the family organization, as shown in the case of Micaela, when her mother has to start doing extra tasks - housework:

I would like to be like my mother. Because my mother is a woman that will never let you down, nothing like that. She had to look for a job when she separated because of gender violence and I took care of my brothers and sisters. Always, she was keeping an eye on us, the four of us always (Jimena’s life story, 2017).

In other situations, the feminization of housework and care giving appears as a relevant determiner in their ways of insertion to the labor world, as in the case of Sonia, who complements housework with temporary jobs - in general, cleaning and/or children care - to add up to the family incomes:

My stepfather was a policeman and got a psychiatric file and my mother has to work in a bakery. I had to work as a babysitter taking care of my nephews, but I stopped doing that because I don’t like children. My mother always had jobs that she didn’t like, she always says that she would have liked to be a flight attendant or a French teacher (Sonia’s life story, 2018).

As we can see, the way of insertion of these young women from popular sectors takes place among unpaid housework and jobs they take in the search of resources and incomes. No doubt, all nonregistered jobs are associated with instability and high level of rotation, as well as the reproduction of the traditional ways of sexual division of work.

Thus, for this group there persist major gender inequalities that strengthen the gap between men and women in the majority of the labor variables such as salaries, jobs and participation. On the other hand, these inequities are reinforced by the learning of trades that they have to acquire from infancy as typically male or female, as Jimena points out:

To be a woman… you have to know that you need to have clean clothes for your child, you have to know how to raise him, but my mother also tells me that I have to defend myself in life, that is why she taught us to fix the home stuff, and electricity to my brothers (Jimena’s life story, 2017).

All in all, the stories contained in the reports reflect that gender as an inequality factor is interwoven from early ages with other socio structural conditions (their places of residence, educational capital, work of their close relatives) producing an overlap of such dimensions that become obstacles difficult to sort for the young women (Frega, 2019).

The Gender Condition: an obstacle to attain upward trajectories

As we could observe in the labor experiences of young women, inequality in relationship with job opportunities is associated not only with inherited social conditions -situations that reproduce or deepen their labor trajectories in the present, but also with the condition of being “women”.

In this way, a configuration of the gender segregation that delimits territories for men and territories for women in the occupational structure prevails. As a consequence, a strong inequality persists, which pushes, for instance, to a minor feminine participation in positions such as supervision, management and directorship (Novick, Rojo, & Castillo, 2008). In this respect, one of the young women says: “My partner tells me that the Police is not a career for a woman. He made me a lot of things, he set impediments and millions of things that made me go back” (Yanina’s life story, 2017). In spite of this, the young woman insists on achieving her goals, that is why she has enrolled at the Socio-Labor Center to learn computing, as well as Sonia, who wants to develop in a labor environment destined to men: “I finish secondary school and I want to enter the Police among the technical agents, you carry guns, watch over security cameras and answer emergency calls” (Sonia’s life story, 2018).

In other instances, you may observe that the condition of being a woman brings about the fact of facing a major discrimination, the jobs tend to have less qualification (call center, food places among others), and they lack aspects such as decent remuneration, access to labor rights as health insurance and social security contributions. In this frame of vulnerability and precariousness, Melina was laid off during her pregnancy:

I worked during the first months of pregnancy, in a place selling pasta or combos, I sold cakes and alfajores1, and I also took care of babies because I realized that I needed to start buying clothes for the baby, but when my pregnancy advanced I was fired (Melina’s life story, 2017).

From the stories you may detect that when the young women are set aside the work environment, the compensation conditions are lower than those of men doing the same activities: “I had to put up with the layoff, my partner told me that they had taken advantage and that I had to denounce them. They gave me less than they should and I was pregnant! (Melina’s life story, 2017). Therefore, regarding the labor market, the sexual division of work is modeled in visible aspects such as the horizontal and vertical segmentation, the salary gap and other types of discrimination (Millenaar, 2014a).

Even though all these experiences delineate informal work trajectories, it is interesting to point out how important it is for the women to learn a trade or to accumulate experiences in order to broaden and improve the options in the market regarding better qualified jobs. Two of the young women retell it in this way:

Once I finished school, I started to work in different places, like in a supermarket during the vacation period. And then my brothers opened a place, a food place. When we closed the food place, I started to work with my father up to now (Clara’s life story, 2017).

I am working in a day care center, in a 3-year-old group with the children. I had different jobs. I began working when I finished secondary school in an ice cream store. Then, I was in charge of it, I was two years there. I was also working in a restaurant for some time, I was also two years there, and well… for example there, in those two jobs I couldn’t do this course. They had discontinuous schedules (Soledad’s life story, 2017).

As we can observe, the possibility of new learning - originated from the different experiences assumed- end up “justifying” unstable occupations which are tolerated as long as they perceive them as a way to build a different trajectory. In this point the expectations in relationship with work imply being able to evaluate in the future, their possibilities of continuity and/or improvement, or therefore taking the opportunity of feeling the necessity to orient their own labor trajectory providing new itineraries (Frega, 2019), thus, delineating diverse ways of paths to adulthood.

Itineraries Concerning the Education - Work Transition

The time passed from the moment when a person stops attending school (whether or not having finished the studies) until the moment when this person inserts in the labor market is a key stage in which the aspects that will mark his or her adult life will be defined (Gontero & Weller, 2015). In the case of the young women interviewed, we could appreciate that the early incorporation to the work market increases the possibility that they quit the educational system, and consequently their future possibilities to obtain quality jobs will be restricted. Therefore, we observe a tension between their expectations and the opportunities given by the society. In relation to this reality, we could detect three itineraries in the transition school - work:

The first one is composed by those young women who quit in the secondary level to start learning a trade and work, as is told by Paola, who quit school to learn a trade:

I quit secondary school, and so, first of all I am about to begin the hairstylist courses. And I want to finish secondary school! Finish secondary school, get a job and have my own house. I imagine the future working, being a professional for sure, that is why I’m going to bite the bullet and start something, do something, you name it. I imagine myself in my house with the hairstylist store (Paola’s life story, 2018).

The second itinerary is the case of the young women who abandon their studies to work and return to them wishing to obtain better jobs. They point out that the lack of complete secondary studies contributes to determine the precariousness where they find themselves when facing the full integration into the labor market:

What I want more is to finish school. I regret a lot (having quit). I’m doing second year. I have to do this year and the next one. Apart from that, it is very difficult to get a job because I haven’t finished secondary school yet. I’d like to work to have my money (Antonella’s life story, 2018).

And the third itinerary is the one of those young women whose pathways are traced between school and work through concrete actions and choices:

Currently I work in a store downtown which sells and repairs speakers. It belongs to my grandfather, and I work there with my father and grandfather. I work from Monday to Saturday. I start work at 9.30 in the morning and finish at 5.30 in the afternoon. When I finish work, I go back home to take a shower and come to school. I’ve worked there for three years, generally I’m at the cash register (Rosalia’s life story, 2018).

I was working until recently and I quit because of the hours and the studies. So I quit. But I’m thinking of going back and try something again right now. I made food for a kiosk where they sold it, before that I took care of a girl, but I only did it for a few months (Rocio’s life story, 2018).

In other cases, maternity makes them think that they have to finish their studies to get better jobs, although their stories reflect the difficulties of the young women to go back to secondary school. The vicious circle that is conformed in the intersection with the caring responsibilities and the vulnerability contexts promotes obstacles when imagining or making the idea of progress tangible (Micha & Pereyra, 2019).

When I realized that I was pregnant I quit school. Sometimes, I feel like finishing, I’m going to see if I can start again. I had in mind that if I had a baby I need a future. I went to T (institute) double shift, sometimes there are workshops in the evening. That’s why I want to see now, this month if I can register, or take a course to get ahead (Jimena’s life story, 2017)

Thus, even though maternity contributes to the constitution of erratic paths with oscillations between the switching of the labor market and the education system, it does not modify in itself the life conditions. On the contrary, it adds up to the inherited structural conditions in which the young women from popular sectors live.

All in all, it becomes significant to analyze the different pathways carried out by the young women and the strategies that they develop to insert in the work market. In the case of the young women who resume their studies, it is clear the necessity to obtain the credential that provides them the opening of new doors in the future. On the other hand, making a lineal reading as regards this objective would imply to deny the value of getting a degree for some young women from these contexts: attaining the graduation from secondary school would imply a qualitative leap with respect to the position of their parents in the labor market.

The incidence of labor qualification in the construction of the future

It is important to note that, in our area, together with the growth of juvenile employment, the net of social policies has been expanding as an attempt to give answers to the situation of the sectors in extreme conditions (Millenaar, 2014b). In this regard, there have been developing in Cordoba a set of actions for the inclusion of the most vulnerable sectors of the population by means of labor qualification for the young population. The Department of Equity and Job Promotion (2018) brings together programs that foresee an economic retribution as the “Program: First Step” for the young people between 16 and 25 years old without a job nor labor experience, “The Program of Integral Formation of Young People in a situation of Social and Labor Vulnerability: We trust you” for young people aged between 14 and 24 years old who do not belong to the formal education system nor to the job world, with professional formation and training in the work places, the “Program: For Me” which is destined to women aged between 18 and 25 years old with dependent children so that they may have access to labor practices for their qualification, and thus being able to obtain work experience.

The participation of the young women in these initiatives becomes an option that in the future reduces the gap regarding the transition education - work. In this context, the socio labor centers that they attend try to improve the educational level of the young women. They develop different strategies among which we may point out the courses of qualification and the formation for employment, being these experiences a way to achieve “better opportunities in the future”, as well as “facing gender inequalities”.

In the first semester I did domestic electricity and now up to December industrial electricity. Then, if I could, I’d like to do electric engineering, and a dream I’d like to fulfill in the future, if I could, is to study safety and health (Clara’s life story, 2017).

The circumstance of being able to improve the labor trajectory marks a significant milestone that they live as a change of life by overcoming the difficulties related to the social and economic conditions: “I want to learn a trade to have money and fit in the future” (Soledad’s life story, 2017).

Accordingly, we may point out that the courses that they decide to attend are not associated with typical feminine tasks since it depends on the offerings of the centers at the moment of their entrance. In this sense, we may observe that the social polices do not always fulfill their objective in connection with the formation offer provided to the women. In general, the focalized policies which are presented do not reflect the complex universe that represents the juvenile group, as in this case in which beyond the age condition there appears the consideration of gender condition. A paradigmatic case is the one of Soledad, who attends a formation center to do a dressmaking course. After starting the first part of it, the government decided to stop the course, so the young women have to insert in another one destined to young men attending the center, as Soledad says:

All of us going there (to study dressmaking) had to change to industrial molding, so the teacher is trying to give a little of dressmaking too, so that we don’t miss everything (Soledad’s life story, 2017)

It is observed that the offer of labor and professional formation does not meet the young women’s needs. Therefore, the gender approach so promoted is not incorporated in practice, and far from overcoming the gender inequalities, it reproduces them (Millenaar, 2014b). Even more, it makes the young women delineate a different future under their condition of “women”.

Discussion and Conclusions

From the analysis of the labor trajectories of young women of popular sectors, we have detected some events and circumstances that account in the singularities brought about in the transition to adulthood.

The qualitative methodology, centered in the perspective of the subjects, shows that the difficulties faced by the young women in the labor market not only can be explained by the conditions proper of the structure or the dynamics of the market, but it also depends on other dimensions. Among them, we have detected that their most objective biographic factors (social and cultural capital) are combined with the subjective factors (perceptions regarding a limited range of work options at their disposal, the expectations in the future connected with the labor area, among others). In this way, we have observed that there may appear risks and disadvantages which provide a reduced margin of election, so that the opportunities and available resources as well as the aspirations and obstacles are intercrossed in the biographical pathways with the issues and tensions which delimit the wide range of disadvantages, only understood from the complex situation of being young, women and poor. Consequently, this results in labor trajectories of informality, fragility or vulnerability of poverty, as shown in other studies (Deleo, 2017).

In this area, some authors have concentrated on comparing the labor trajectories of the young women from the middle and working classes. The results indicate that concerning the young women from middle and middle-high classes the precarious work is only a stage towards a stable job while for the young women from popular sectors this situation is transformed into a lasting condition in the work market (Benza, 2012; Muñiz Terra & Roberti, 2018).

So, we may sustain that although the participation of the women in the work market and the sexual distribution of the income show a growing tendency in the long term, this does not mean that the labor reality of the young women from popular sectors has improved. As it is reflected in the investigations, the social background origin determines significant differences: the employment rate and activity increase as far as it increases the socio-economic level of the belonging homes. That is why we suggest the necessity to articulate the analysis with those related to class belonging (Gorban & Tizziani, 2018).

Moreover, the study has permitted to confirm that the opportunities granted by the device of professional formation would give way to transitions, for some women more and for other women less favorable. In accordance with recent studies, it is observed that the public policy acquires a key role to soften these inequities as they derive in strong incentives for the completion of formative projects (Micha, & Pereyra, 2019).

Seemingly, the considerations derived from the stories of the young women make us reflect about the features existing in the labor participation of the young women from popular sectors. As sustained by Micha (2017) even though these aspects affect the female work force in general, no doubt the women with lower incomes are the ones who face the more significant obstacles and exclusions in this area. All in all, this point could be a core element to orient, model and modulate the process of transition to adulthood (Miranda & Corica, 2018).

Finally, we point out the necessity of an in-depth comprehension of the study of the labor insertion of the young women from popular sectors. On the one hand, it demands us to divert from lineal readings which only privilege the structural analysis and to incorporate the analysis concerning the subjective factors, since the expansion of the educational and labor inequalities positions us in the necessity to design and implement policies oriented to this juvenile group, policies that take into account their life conditions looking at the future.

REFERENCES

Aisenson, G., Legaspi, L., Valenzuela, V., Bailac, K., Czerniuk, R., Vidondo, M., … Gómez González, M. (2015). Temporalidad y configuración subjetiva: Reflexiones acerca de los proyectos de vida de jóvenes en situaciones de alta vulnerabilidad social Anuario de investigación 22(1), 83-92. [ Links ]

Arancibia, M., & Miranda, A. (2017). Modelos normativos, empleo y cuidados: las trayectorias de las mujeres jóvenes en el Gran Buenos Aires. En D. Beretta, E. Cozzi, M. Estevez, & R. Trincheri (comps.) Estudios sobre juventudes en Argentina V: juventudes en disputa: permeabilidad y tensiones entre investigaciones y políticas (pp. 186-196). Rosario: Facultad de Derecho. Universidad Nacional de Rosario. [ Links ]

Arnett, J. J. (2015). The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Benza, G. (2012). Estructura de clases y movilidad intergeneracional en Buenos Aires: ¿el fin de una sociedad de “amplias clases medias”?, tesis de doctorado, Centro de Estudios Sociológicos, El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Bukstein, G. (2019). Trayectorias laborales de mujeres pobres urbanas ¿Con trabajo registrado se supera lapobreza?. En R. Tunes, A. L. Bialakowsky, F. Pucci, & M. Quiñones (coords). Trabajo y capitalismo: relaciones y colisiones sociales (pp.299-315). Buenos Aires: Teseo. [ Links ]

Casal, J., García, M., Merino, R., & Quesada, M. (2006). Aportaciones teóricas y metodológicas a la sociología de la juventud desde la perspectiva de la transición. Papers de Sociología, (79), 21-48. [ Links ]

Castel, R. (2012). Prólogo. En G. Pérez Soto, & M. Romiero Futuros inciertos. Informe sobre vulnerabilidad, precariedad y desafiliación de los jóvenes en el conourbano bonaerense (pp. 9-17). Buenos Ares: Instituto Torcuato Di Tella. [ Links ]

Cornejo, M., Mendoza, F., & Rojas, R. (2008). La investigación con relatos de vida: pistas y opciones del diseño metodológico. Psykhe, 17(1), 29-39. doi: 10.4067/S0718-2228200800010000 [ Links ]

Deleo, C. (2017). Trayectorias laborales de jóvenes urbanos argentinos: un análisis de los cambios y continuidades en los sentidos laborales. Nueva antropología, 30(87),47-65. [ Links ]

Dirección de Información y Estadística Educativa (DIEE) (2018). Caracterización de la población de 15 a 24 años que no asiste a la escuela ni trabaja (Boletines de Estadística N° 4 ). Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, Ciencia y Tecnología, Presidencia de la Nación Argentina. Recuperado de https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/04-serie-boletines-nini02-05-2019.pdf [ Links ]

Frega, G. (2019). Mujeres y trabajos en el conurbano reciente (Argentina). Apuntes en clave feminista. Revista latinoamericana de Antropología del trabajo, 3(5), 1-28. [ Links ]

Furlong, A. & Cartmel, F. (1997). Young people and social change: individualisation and risk in the age of high modernity. Buckingham, ReinoUnido: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Gontero, S., & Weller, J. (2015). ¿Estudias o trabajas? El largo camino hacia la independencia económica de los jóvenes de América Latina. Serie Macroneconomía del Desarrollo. Santigo de Chile: Cepal. Naciones Unidas. Recuperado de https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/39486-estudias-o-trabajas-largo-camino-la-independencia-economica-jovenes-america [ Links ]

González Rey, F. (2008). Subjetividad social, sujeto y representaciones sociales. Revista Diversitas-Perspectiva en Psicología, 4(2), 225-243. [ Links ]

Gorban, D. & Tizziani, A. (2018). Las ocupaciones en los servicios de limpieza y de estética: algunas pistas para reflexionar en torno de la movilidad laboral de las mujeres de sectores populares en Argentina. Revista Internacional de Organizaciones, 20, 81-102 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC) (2019). Mercado de trabajo. Tasas e indicadores socioeconómicos (Encuesta Permanente de Hogares, EPH) Cuarto trimestre de 2019. Ciudad Autómoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ministerio de Hacienda, Presidencia de la Nación Argentina. Recuperado de https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/mercado_trabajo_eph_1trim19B489ACCDF9.pdf [ Links ]

Leclerc-Olive, M. (2009). Temporalidades de la experiencia: las biografías y sus acontecimientos. Iberóforum. Revista de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Iberoamericana, IV (8), 1-39. [ Links ]

Machado Pais, J. (2007). Chollos, chapuzas y changas. Jóvenes, trabajo precario y futuro. Barcelona: Antrhopos. [ Links ]

Micha, A. S. (2017). Lógicas detrás de la participación laboral de mujeres de sectores populares del Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires. En P. Rojo, & A. Sahakian (comps.) Mujer y mercado del trabajo (pp. 49-80). Rosario, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Rosario. Programa Género y Trabajo. Recuperado de https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/76234 [ Links ]

Micha, A., & Pereyra, F. (2019). La inserción laboral de las mujeres de sectores populares en Argentina: sobre características objetivas y vivencias subjetivas. Sociedade e Cultura. Revista de Pesquisa e Debates em Ciências Sociais, 22, (1), 88-113.DOI: 10.5216/sec. v22i1.57887 [ Links ]

Millenaar, V. (2014a). Trayectorias de inserción laboral de mujeres jóvenes pobres: El lugar de los programas de Formación Profesional y sus abordajes de género. Trabajo y Sociedad, 22, 325- 339. [ Links ]

Millenaar, V. (2014b). ¿Capacitar para la competitividad o promover los derechos? Retóricas de la formación profesional desde un análisis de género. Propuesta Educativa, 23(41), 99-108. [ Links ]

Millenaar, V. & Jacinto, C. (2015). Desigualdad social y género en las trayectorias laborales de jóvenes de sectores populares. El lugar de los dispositivos de inserción. En L. Mayer, D. LLanos, & R. Unda Lara (comps.) Socialización escolar: experiencias, procesos y trayectos (pp.73-100). Ecuador: Abya Ayala, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, CINDE - CLACSO. [ Links ]

Miranda, A., & Corica, A. (2018). Gramáticas de la Juventud: reflexiones conceptuales a partir de estudios longitudinales en Argentina. En A. Corica, A. Freytes , & A. Miranda (comps.), Entre la educación y el trabajo. La construcción cotidiana de las desigualdades juveniles en América Latina (pp.27-50). Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [ Links ]

Muñiz Terra, L. & Roberti, E. (2018). Las tramas de la desigualdad social desde una perspectiva comparada: hacia una reconstrucción de las trayectorias laborales de jóvenes de clases medias y trabajadora. Revista Estudios del Trabajo, 55, 1-32. [ Links ]

Novick, M., Rojo, S., & Castillo, V. (comps.) (2008). El trabajo femenino en la post convertibilidad. Argentina 2003 - 2007. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL, GTZ, Ministerio de Trabajo, Empleo y Seguridad Social. [ Links ]

Observatorio de la Deuda Social Argentina (ODSA) (2018). Juventudes desiguales: oportunidades de integración social. Jóvenes entre 18 y 29 años en la Argentina urbana. Informe Especial. EDSA Serie agenda para la equidad (2017-2025). Barómetro de la deuda social Argentina. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Educa. [ Links ]

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, United States of America: SAGE. [ Links ]

Roberti, E. (2017a). Hacia una crítica a la sociología de la transición: reflexiones sobre la paradoja de la desinstitucionalización en el análisis de las trayectorias de jóvenes vulnerables en Argentina. Estudios Sociológicos de El Colegio de México, XXXV (105), 489-516. En Memoria Académica. Recuperado de: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.7798/pr.7798.pdf [ Links ]

Roberti, E. (2017b). Perspectivas sociológicas en el abordaje de las trayectorias: un análisis sobre los usos, significados y potencialidades de una aproximación controversial. Sociologías, 19(45),300-335. [ Links ]

Rodriguez Enriquez, C., & Marzonetto, G. (2016). Organización social del cuidado y desigualdad: el déficit de políticas públicas de cuidado en Argentina. Revista Perspectivas de Políticas Públicas, 4(8), 103-134. doi: 10.18294/rppp.2015.949 [ Links ]

Secretaría de Equidad y Promoción del Empleo (2018). Programas de empleo. Gobierno de la Provincia de Córdoba. Recuperado de https://programasdeempleo.cba.gov.ar/ppp [ Links ]

Financing: This article of scientific and technological investigation is part of a project named “Processes of Subjectivity of the young people in poverty contexts: Trajectories and Life Projects”, financed by the Catholic University of Cordoba and filed in the Investigation Department and Unit Associated to Conicet/Area of Social Sciences and Humanities /School of Philosophy and Humanities. Dean Resolution N 991/16. Period 2016 - 2018

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. G. C. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e ; A. S. G. in a, b,c,d,e.

How to cite: Cardozo, G., & González, A. S. (2020). Trayectorias laborales de mujeres de sectores populares en transición hacia la vida adulta. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2210. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2210

Received: September 16, 2019; Accepted: May 19, 2020

texto en

texto en