Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 28-Mayo-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2201

Original Articles

Perception of gender equity and work-family balance in workers belonging to public and private companies in Chile

1 Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Talca. Chile anjimenez@utalca.cl,agus.hndez.r@gmail.com

It is analyzed whether there are significant differences in the Perception of Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance in workers belonging to public and private companies. The instruments Work-Family Balance (Moreno, Sanz, Rodríguez & Geurts, 2009) and Gender Equity Perception (Gómez & Jiménez, 2015) were applied to 300 workers from public and private companies. It is observed that there are statistically significant differences between workers belonging to public and private companies in the levels of Gender Equity Perception and Work-Family Balance, where workers in private companies have a higher Gender Equity Perception. Likewise, they have a higher perception of Work-Family Balance. There are significant and positive correlations between the perception of gender equity and work-family balance. It is concluded that the companies present differences in their actions in favor of establishing good reconciliation practices that have an impact on the perception of equity.

Keywords: gender equity perception; work-family balance; public companies; private companies

Se analiza si existen diferencias significativas en la Percepción de Equidad de Género y Equilibrio Trabajo-Familia en trabajadores pertenecientes a empresas públicas y privadas. A 300 trabajadores de empresas públicas y privadas, se les aplicaron los instrumentos, Equilibrio Trabajo-Familia (Moreno, Sanz, Rodríguez & Geurts, 2009) y Percepción de Equidad de Género (Gómez & Jiménez, 2015). Se observa que existen diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los trabajadores pertenecientes a empresas públicas y privadas en los niveles de Percepción de Equidad de Género y Equilibrio Trabajo-Familia, donde los trabajadores de empresas privadas tienen una mayor Percepción de Equidad de Género. Asimismo, presentan una mayor percepción de Equilibrio Trabajo-Familia. Se presentan correlaciones significativas y positivas entre Percepción de Equidad de Género y Equilibrio Trabajo-Familia. Se concluye que las empresas presentan diferencias en sus accionar en pro de establecer las buenas prácticas de conciliación que repercuten en la percepción de equidad.

Palabras clave: percepción de equidad de género; equilibrio trabajo-familia; empresas públicas; empresas privadas

Se analisa a existência de diferenças significativas na percepção de equidade de gênero e equilíbrio entre trabalho e família em trabalhadores de empresas públicas e privadas. Para 300 trabalhadores de empresas públicas e privadas, foram aplicados os instrumentos de Equilíbrio Trabalho-Família (Moreno, Sanz, Rodríguez & Geurts, 2009) e Percepção da Equidade de Gênero (Gómez & Jiménez, 2015). Observa-se que existem diferenças estatisticamente significativas entre trabalhadores de empresas públicas e privadas nos níveis de Percepção da Equidade de Gênero e Equilíbrio Trabalho-Família, na qual trabalhadores de empresas privadas apresentam maior Percepção de Equidade de Gênero, assim como, apresentam uma maior percepção do Equilíbrio Trabalho-Família. São apresentadas correlações significativas e positivas entre a Percepção da Equidade de Gênero e o Equilíbrio entre Trabalho e Família. Conclui-se que as empresas apresentam diferenças em suas ações em pro de estabelecer boas práticas de conciliação que impactam a percepção da equidade.

Palabras-chave: percepção de eqüidade de gênero; equilíbrio trabalho-família; empresas públicas; empresas privadas

Introduction

Work and family are two important areas for the personal and social development of citizens (Marín, Infante & Rivero, 2002). One of the biggest and most common problems in the world of work has been women's access to it. This process has led to changes in the history of the role that women have played in society, which is related to domestic and upbringing tasks, while that of men is related to the role of provider and breadwinner in the family. This conception has been changing in recent years, due to changes in family structure and greater access by women to education and more flexible working conditions (Jiménez & Moyano, 2008).

According to Gómez and Martí (2004), the access of women into paid work has presented difficulties for families, since both men and women have to dedicate proportionally more time to work than to home, and this leads to fatigue and stress. Balancing work and family with the obligation to admit the variety of roles creates conflict and stress in the person (Riquelme, Rojas & Jiménez, 2012).

In relation to the redistribution of roles within the family, which arises from the incorporation of women into the workplace, it is important to mention the responsibility that organizations have in terms of reconciling work and family through the implementation of organizational practices specifically commissioned in these areas (Caballer, Peiró & Sora, 2011). These policies implemented by the organizations favor work-family conciliation as perceived by the workers, who in turn improve performance in their jobs (Anderson, Coffey & Byerly, 2002). The appreciations that workers have about the support given by their organization in family issues, is related to the perception of organizational support (Allen, 2001). This is shown by a study carried out by Besarez, Jiménez and Riquelme (2014) with 137 workers that compares companies with and without organizational policies in work-family balance issues, in which it was observed that there were significant differences in terms of the organizational support perceived towards the family and work satisfaction.

This is why companies implement organizational policies that assume social responsibility, safeguarding the quality of life of workers. According to Servicio Nacional de la Mujer SERNAM (2003), these policies are indicated as all those initiatives, additional to those established by law, adopted by organizations with the objective of contributing to good labor practices and thus, improving the performance and adherence of employees to the company (Abarca & Errázuriz, 2007). To the same end, gender equity or work-family conciliation practices are created. One of the initiatives to enrich gender equity within companies was implemented by SERNAM (2017) by creating the IGUALA model between 2007 and 2012, which follows a plan that is transversal for both public and private companies, as well as for large, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), contemplating all workers belonging to the organization and focused on the eradication of gender differences. Among the actions carried out through this model, the following stand out (SERNAM, 2017, p. 8)

The commitment to increase the number of women and equal opportunities between women and men in the selection and internal promotion process. The effort to achieve balanced mixed teams, ensuring quotas for women in training activities commonly targeted at men. The carrying out of information and training activities on the importance of equality in labor relations and the prevention of violence and sexual and labor harassment. The development of initiatives for the protection of maternity, i.e., for example, the organization of working hours for pregnant women. The implementation of actions to reconcile work, family and personal life through a progressive return from the post-natal period up to 9 months of the child's life. The extension of the male postnatal period by adding three additional days to those considered by the law. The provision of childcare and school tutoring services for the children of workers; and the implementation of a flexible working day.

The model was accepted by 79% of the Chilean workers surveyed in 2011, who showed positive changes to the gender equity approach. On the other hand, in Chile, there is a national platform, called the Gender Parity Initiative (IPG), which is carried out by authorities belonging to the government and representatives of the private sector. The aim is to bring more women into the economy and end gender inequalities in both the public and private sectors (Comunidad Mujer, 2016). It is important to point out that integrating the gender perspective in enterprises generates enthusiasm for creating practices oriented to women's development, where they can feel equal, strengthening their commitment to the organization (Stevens & Van Lamoen, 2001).

Not implementing labor measures specifically aimed at reconciling family and work, damages the quality of life of the worker, reflecting in desires of abandonment, when this is interfered by the incompatibility of family tasks (Boles, Johnston & Hair, 1997) and the decrease of satisfaction caused by their employment, affecting their well-being, which is reflected in physical problems, such as fatigue and stress, and mental problems, such as worry and guilt (Greenglass, 1985).

The strong insertion of women in the labor market not only posed problems in the family dynamics, but also within their jobs, where there are great gender differences. This is pointed out by Comunidad Mujer (2016) when it states that women's participation in the labor market does not ensure equality with the opposite gender, since in this context there are several discriminations, segmentation situations and several other difficulties that are detrimental to their salaries (National Institute of Statistics, 2015) and the opportunities they have to apply for more important or leadership positions. Under this point, measures have been implemented that target good labor practices by promoting gender equity within organizations, since promoting equality between men and women promotes economic efficiency and has a positive impact on other areas of economic or personal development (World Bank, 2012). In addition, adopting organizational practices that are not equitable between men and women can lead to feelings of injustice, which affect performance within the company, causing a dissociation from their work (Lambert, Hogan & Barton, 2001).

On the other hand, domestic work has come to be recognized by international organizations as a job, which is closely related to the concept of the double shift (Ruvalcaba, 2001). This is because the time spent on work is done by virtue of the time spent on domestic work, thus creating the double shift, and as women increase as wage-earning or non-wage-earning workers, they will do so by virtue of this condition (Hirata & Zariffian, 2007). For its part, the OECD (2010) reports that in Chile there is a high number of hours that people spend in their workplace, totaling approximately 2000 hours per year. In this regard, the National Institute of Statistics (2016) shows that during 2015 in Chile 28.2% of women worked an average of 1 to 30 hours per week, while those who worked 31 to 44 hours represented 19.9%.

In this regard, this strong incorporation of women into the work environment provides a new vision of family dynamics, modifying roles and adding the role of producer, if observed from the perspective of the traditional family model, a new concept of family is proposed. It has been possible to perceive, during the last time, the changes that have been generated in the structures and family dynamics. Factors such as greater access to education, falling fertility rates and the growing need to incorporate economic income into the household (Abramo & Valenzuela, 2006) have changed the forms of work and employment and have promoted the redistribution of the roles assigned to men and women, replacing the role of men as the sole provider of the household with the incorporation of women into paid work. This change generates transformations in economic, social and political life, reflected in the distribution of responsibilities between men and women within the family, which generates conflicts between work and family, because of the demands and incompatibility that these two contexts cause, causing a drain on a person's energy (Guerrero, 2003). In addition, it is possible to observe these transformations in people who choose to live alone, in couples and without children, in single-parent homes and in unions of mutual agreement.

It should be noted that the existing gender inequalities correspond to the patriarchal model that dominated Chilean society which, culturally speaking, differentiates the roles belonging to men and women, where the former focus their lives on work, being the breadwinner and reducing their participation in family tasks, and not the woman, who follows the traditional role of employing various roles, such as housewife, mother, wife and worker. However, the existing gender distinctions today are not only dictated by the concept of society, but also by the existing prejudice about the lack of work experience (Heilman, 2001) and by the inability of women to perform efficiently and consistently in work tasks, since these are carried out at a fertile age (Lorenzini et. al., 2013).

All this is reflected by the growing male labor participation, which according to the INE survey (2018) corresponds to a percentage of 71.1%, compared to 49% for women. 3%, by the differences in wages, which the ESI survey conducted in 2017 indicates is equal to U$228 per month between men and women (Durán & Kremerman, 2018) and, by the different types of labor discrimination, such as horizontal segregation, which refers to jobs carried out by women who are scarce in activity and profession and, vertical segregation, which is understood as jobs at the bottom of the hierarchy, according to positions within an organization (Maruani, 1993). One of the reasons for this problem is the assignment of the protective role given to women in the care of children, which makes them the main responsible for the costs of reproduction, since according to Comunidad Mujer (2017):

Most women receive lower salaries than men due to the employer's punishment of women of childbearing age, in anticipation of the eventual cost of pre- and post-natal care, maternity leave, the right to food, crèche and/or absences of young children in case of illness or other reasons (p. 10).

The objective of this work is to evaluate if there are differences in the perception that workers, belonging to public or private companies, have about the Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance variables within their companies.

The specific objectives are:

Determine if there are differences in the perception of Gender Equity among workers in a public and a private company.

To determine if there are differences in relation to the Work-Family Balance in the workers of a public and a private company.

Describe the relationship between the Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance variables of the total sample.

Based on the reported background, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1: There are statistically significant differences in the perception of Gender Equity between a public and a private company.

H2: There are statistically significant differences in the Work-Family Balance between a public and a private company.

H3: There is a strong and positive relationship between the Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance variables applied to the total sample.

Method

Participants

The study included a sample of 300 workers, 150 women and 150 men, distributed equally between a public and a private organization. The sample was chosen on a non-probability basis and for convenience. The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 64 years, with an average of 38 years. Of the total sample, 35.7% are married, 33% are single, 21.7% say they are in a couple, 5.3% are separated, 3% are divorced, and finally 0.7% are widowed. In terms of the number of children each participant in the sample has, it can be seen that 29.7% have no children, 55.3% have 1 or 2 children and 11.3% have 3 or more children.

Instruments

SWING questionnaire (Moreno, Sanz, Rodríguez & Geurts, 2009). This instrument consists of 22 items with a Likert type scale with answers from 0 to 3, where 0 is never, 1 sometimes, 2 often and 3 always. The items are distributed in 4 subscales, which are presented as follows: Negative work-family interaction (8 items), Negative family-work interaction (4 items), Positive work-family interaction (5 items), and Positive family-work interaction (5 items). The Spanish validation of the instrument by Moreno et al. (2009) showed Cronbach's Alpha indexes between .77 and .89, these being indicators of a high reliability of the questionnaire.

Gender Equity Perception Questionnaire (Gómez & Jiménez, 2015). This questionnaire consists of 14 Likert-type items, where the answers range from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. In addition, they are distributed in 4 subscales, which are Perception of availability of personal time (3 items), Perception of distribution of household care responsibilities (5 items), Perception of distribution of household financial support responsibilities (3 items), and Perception of distribution of labor demands (3 items). The validation of the instrument by Gómez and Jiménez (2015) yielded a Cronbach's Alpha index of .87, which is a highly reliable indicator of the questionnaire (Jiménez & Gómez, 2019).

Procedure

First, an institutional mail was sent to public and private companies, explaining the purpose of the research, in order to obtain their support and authorization. Then, contact was made with the people in the sample, through meetings with professionals from Human Resources, Sub-Directorate, Labor Relations and Head of Welfare. Finally, the application of the battery of instruments was carried out, inviting each staff member personally and voluntarily to his or her workplace, which is stipulated in an informed consent, which is read together with the volunteers before carrying out the questionnaire, in paper format.

Design and data analysis

Correlational cross-sectional study. The data were processed and analyzed by the statistical program SPSS, carrying out descriptive and correlational analyses. Since the assumption of normality for the distribution of the variables under study (Kolmogorov Smirnov p < 0.5) was fulfilled, parametric tests were used.

Results

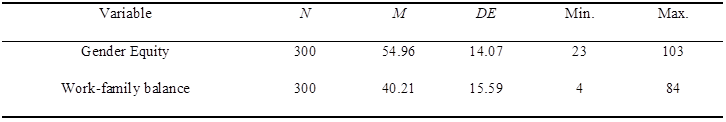

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance variable.

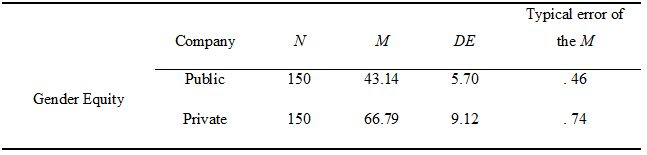

With respect to the variable Gender Equity Perception, the public company presents an average of 43.14 and the private company an average of 66.79 (see Table 2).

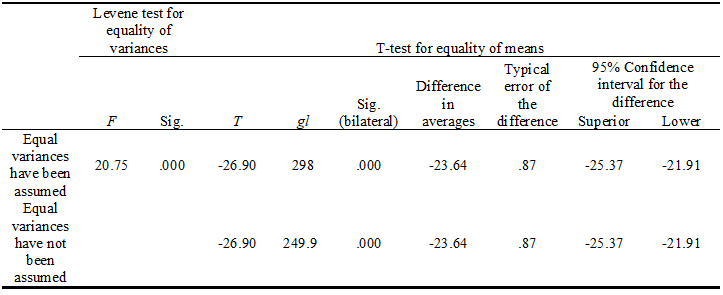

By means of the analysis carried out through the T test for independent samples in which inequality of variance has been assumed (F = 20.75; p < .05) it is possible to point out that there are statistically significant differences in relation to the Gender Equity Perception between the public company and another private company (t = -26.90; p < .05) (see Table 3).

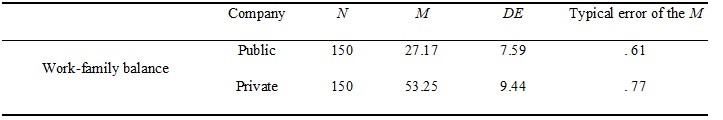

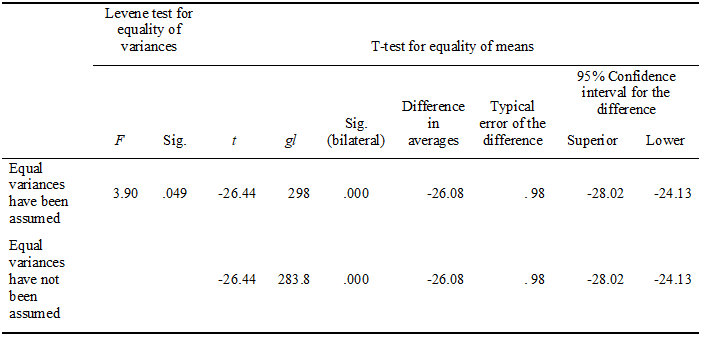

With regard to the variable Work-family balance, the public company presents an average of 27.17 and the private company an average of 53.25. By means of the analysis carried out by means of the T test for independent samples (see Table 4) in which inequality of variance has been assumed (F = 3.90; p < .05) it is possible to indicate that statistically significant differences exist in relation to the Work-Family Balance between the public company and another private company (t = -26.44; p < .05) (see Table 5).

It can be seen that there is a strong and positive correlation between the variables Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance (r = .796, p < .05).

Discussion and Conclusions

The objective of this research was to determine if there are differences in the perception of gender equity and in relation to the work-family balance in workers belonging to a public and a private company in Chile. To this end, three hypotheses were put forward, which will be described below by discussing the results obtained.

In relation to hypothesis 1, it is proposed that there are statistically significant differences in the perception of gender equity among the enterprises. As for their characteristics, it can be mentioned that they differ in their modes of operation.

On the one hand, despite the constant effort that state organizations make to achieve the welfare of their workers, this is impaired by the different goals or purposes shared by the stakeholders who make decisions within the organization, either by the sharp variations in the staff that make up the management as a result of changes of government, or by the objectives expected by parliamentarians, which may differ from the rest. In turn, within these companies there are groups that seek to resolve their own interests without thinking about the opinion of others (Hernández & Argimon, 2000). In contrast, private companies have a direct relationship between managers and their workers, ensuring their health and welfare through short, medium and long term measures (Trujillo & Vargas, 1996). It should be noted that these organizations live at an accelerated and dynamic pace, seeking innovations to increase their profits (Merlano, 1983).

On the other hand, according to the results obtained in the application of the SUSESO/ISTAS 21 questionnaire, the public sector showed a higher percentage of women in its organizations (39.8% men and 60.2% women) than the private sector (51.6% men and 48.4% women), which leads us to expect that perceptions will differ as a result of the number of workers belonging to one sector or another (Social Security Superintendency, 2017).

The results obtained in this study confirm the existence of statistically significant differences in the Perception of Gender Equity between a public and a private company (p < 0.5), resulting that, workers belonging to the private company have a greater perception of gender equity than workers belonging to the public company.

In the studies carried out by Hofstede (1990) in 20 public and private organizations in the Netherlands and Denmark, it is mentioned that such organizations differed in terms of their implemented practices, which had much to do with the system of control by the managers, the performance of the task and the hierarchization of the company. On the other hand, Gilbreath (2004) propose that organizational policies have better results in the workers, when they involve a more personal relationship between management and subordinates, such as those that can be observed in private companies, thus creating a homogeneous group within which each implemented measure will benefit the whole group. The perceptions that individuals have about these organizational practices and about the tasks carried out within the work environment will be oriented towards improving the climate within the company (Goncalves, 2002).

Hypothesis 2 of this work raised the existence of statistically significant differences in relation to the Work-Family Balance between a public and a private company. The implementation of organizational practices that promote work-family balance is linked to the work that companies do, specifically in the area of human resources, in order to protect their employees, provide them with well-being and satisfaction and avoid absenteeism or resignations (Cappelli, 2000). It is expected that companies in the public and private spheres will differ in their management, which will differ from one another in their actions.

The results presented in this study confirm the existence of statistically significant differences in relation to the Work-Family Balance between a public and a private company (p < 0.5), with the result that workers belonging to the private company report a greater work-family balance than workers belonging to the public company.

According to the literature reviewed by Idrovo (2006) on studies carried out in private companies, it is observed that the organizational policies that integrate these institutions are linked to production and efficient work by employees, that is, they implement practices of work-family conciliation to retain their more efficient workers and increase productivity. In addition, these are related to the worker's job satisfaction, reduction of stress and commitment to and with the company. On his part Allen (2001) mentions that the perception of support that the workers have by the company has a positive relation with the accomplishment of the tasks that these have in their two more important scopes, work and family.

Finally, hypothesis 3 stated that there is a positive correlation between the Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance variables applied to the total sample. According to the above, it can be pointed out that solving the conflict generated by trying to reconcile work and family would benefit the women who belong to the company, as well as the implementation of practices such as: part-time work and reducing the double working day, assuming shared responsibilities, which would be linked to the principle of gender equality and work-family balance (Papi, 2005).

The results observed in this study confirm the existence of a strong and positive correlation between the variables Gender Equity and Work-Family Balance (r= .796, p < .05) applied to the total sample.

The literature reviewed shows that the social and political changes that have occurred, in terms of the redistribution of men's and women's roles, have generated conflicts between work and family. The need to increase household income has been modifying family dynamics, such as women's entry into paid work. Access to work by both parents generates problems in reconciling work and family, not only for women but also for men, who have had to become more involved in household tasks (Idrovo, 2006).

With regard to the limitations of this investigation, it can be noted that a sample was used that does not represent the totality of companies, both public and private, in the country, and therefore the results cannot be generalized. At the same time, no differences could be determined between these companies, including only the questionnaires applied. In turn, the institutions compared belong to different headings, which could interfere with the results obtained.

Despite the fact that organizational practices are created to encourage worker motivation, procure their welfare and strengthen their commitment to the company, there is little empirical evidence as to how they are carried out within organizations and if they are feasible in these areas, thus generating a limitation to the incorporation and creation of policies on issues of work-family balance and gender equity.

To this effect, it is proposed to emphasize a design that incorporates a more complete analysis, encompassing both qualitative and quantitative techniques, incorporating the opinion of the interviewees, on the understanding that, due to the strong psychosocial changes occurring worldwide, life projections, both personal and professional, are different from one worker to another, which may interfere with the levels of perception of gender equity or work-family balance. At the same time, integrating other variables such as family co-responsibility will benefit the results that can be extracted from such a design, since assuming the tasks that a household entails between men and women in an equitable manner will improve the balance in the work-family spheres (Dirección del Trabajo, 2015). It is necessary to evaluate the practices oriented to reconcile work and family within the organizations, since these can be giving solution to the conflict generated between these contexts improving the perception of support that the workers have about their company, that is why it is suggested to integrate the variables culture and organizational support to reinforce the effectiveness in which these measures are carried out. Finally, it is important to evaluate the type of position that women have in the companies studied and the policies that the companies have implemented when applying the study, since, according to citizen evaluation workshops applied by law, the perception of gender inequality is mostly present in women (63%) than in men (52%) and is reflected in the organizations with directors or managers, which means that unequal pay would be more detrimental to women in the professional field (Dirección del Trabajo, 2015), so perceptions differ depending on the hierarchy or structure of the organization

REFERENCES

Abarca, N. y Errázuriz, M. (2007). Propuestas para la Conciliación Trabajo y Familia, en Camino al Bicentenario. Propuestas para Chile, Pontifica Universidad Católica. Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Abramo, L. & Valenzuela, M. (2006). Inserción laboral y brechas de equidad de género en América Latina. En L. Abramo (Ed.), Trabajo decente y equidad de género en América Latina (pp. 9-62). Santiago, Chile: Organización Internacional del Trabajo. [ Links ]

Allen, T. (2001). Family-Supportive Work Environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 414-435. Doi: 10.1006 / jvbe.2000.1774 [ Links ]

Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. S., & Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal Organizational Initiatives and Informal Workplace Practices: Links to Work-Family Conflict and Job-Related Outcomes. Journal of Management, 28(6), 787-810. Doi: 10.1177/014920630202800605 [ Links ]

Banco Mundial (2012). Informe Sobre el Desarrollo Mundial: Igualdad de Género y Desarrollo, Panorama General. Recuperado de: https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDR2012/Resources/7778105-1299699968583/7786210-1315936231894/Overview-Spanish.pdf [ Links ]

Besarez, F., Jiménez, A. & Riquelme, E. (2014). Apoyo organizacional hacia la familia, corresponsabilidad y satisfacción laboral según tipo de políticas organizacionales de equilibrio trabajo‐familia. Trabajo y Sociedad, 23, 525-535. [ Links ]

Boles, J., Johnston, M., & Hair, J. (1997). Role stress, work-family conflict and emotional exhaustion: Interrelationships and effects on some work-related consequences. Journal of Personnel Selling & Sales Management, 17(3), 51-52. Doi: 10.1080 / 08853134.1997.10754079 [ Links ]

Caballer, A., Peiró, J. M., & Sora, B. (2011). Consecuencias de la inseguridad laboral. El papel modulador del apoyo organizacional desde una perspectiva multinivel. Psicothema, 23(3), 394-400. [ Links ]

Cappelli, P. (2000). A market driven approach to retaining talent. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 103-111. [ Links ]

Comunidad Mujer. (2016). Iniciativa paridad de género en Chile. Documento técnico. Recuperado de: http://www.comunidadmujer.cl/wpcontent/uploads/2016/12/2016 _12_07-Documento-Ejecutivo-t%C3%A9cnico_VF.pdf [ Links ]

Comunidad Mujer. (2017). Para un Chile sostenible: 10 propuestas de género. Documento técnico. Recuperado de: http://www.comunidadmujer.cl/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09 Propuestas_Digital_PL-1.pdf [ Links ]

Dirección del Trabajo (2015). La Desigualdad Salarial entre hombres y mujeres. Cuadernos de investigación 55. Recuperado de: https://www.dt.gob.cl/portal/1629/articles-105461_recurso_1.pdf [ Links ]

Durán, G. & Kremerman, M. (2018). Los Verdaderos Sueldos de Chile: Panorama Actual del Valor de la Fuerza del Trabajo Usando la ESI 2017. Estudios de la Fundación Sol. Recuperado de: http://www.fundacionsol.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Los-Verdaderos-Salarios-NESI-2017-1.pdf [ Links ]

Gilbreath, B. (2004). Creating healthy workplaces: The supervisor’s role. In C. L. Cooper I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 93-118). Chichester, England: Wiley [ Links ]

Gómez, S. & Martí, C. (2004). La incorporación de la mujer al mercado laboral: Implicaciones personales, familiares y profesionales, y medidas estructurales de conciliación trabajo-familia. Documentos de Investigación Núm. 557. Barcelona: IESE Business School, Universidad de Navarra.: 49. [ Links ]

Gómez, V. & Jiménez, A. (2015). Corresponsabilidad familiar y el equilibrio trabajo-familia: Medios para mejorar la equidad de género. Polis, 14(40), 377-396. [ Links ]

Goncalves, A. (2002) Dimensiones del clima organizacional. Recuperado de: http://www.geocities.ws/janethqr/liderazgo/130.html [ Links ]

Greenglass, E. (1985). Psychological implications of sex bias in the workplace. Academic Psychology Bulletin, 7, 227-240. [ Links ]

Guerrero, J. (2003). Los roles no laborales y el estrés en el trabajo. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 12, 73-84. [ Links ]

Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57. 657-673. Doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00234 [ Links ]

Hernández, P., Argimón, I. & González-Páramo, J. M. (2000). ¿Afecta la titularidad pública la eficiencia empresarial? evidencia empírica con un panel de datos del sector manufacturero español. España: Imprenta del Banco de España. [ Links ]

Hirata, H. & Zariffian, P. (2007). El concepto de trabajo. Revista de Trabajo, 3(4), 33-36. [ Links ]

Idrovo, S. (2006). Las políticas de conciliación trabajo-familia en las empresas colombianas. Estudios gerenciales, 22(100), 49-70. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2015). Encuesta Suplementaria de Ingresos. Recuperado de: https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/ingresos-y-gastos/encuesta-suplementaria-de-ingresos [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2016). Enfoque estadístico: Género y empleo. Recuperado de: https://www.ine.cl/docs/defaultsource/laborales/ene/publicaciones /g%C3%A9nero-y-empleo---enfoque estad%C3%ADstico-mayo-2016.pdf?sfvrsn=4 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2018). Compendio estadístico 2018. Recuperado de: https://www.ine.cl/docs/defaultsource/publicaciones/2018/bookcompendio2018.pdf?sfvrsn=fae156d2_5 [ Links ]

Jiménez, A., & Moyano, E. (2008). Factores laborales de equilibrio entre trabajo y familia: medios para mejorar la calidad de vida. Revista Universum, 23(1), 116-133. [ Links ]

Lambert, E., Hogan, N. & Barton, S. (2001). The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Turnover Intent: A Test of a Structural Measurement Model Using a National Sample of Workers. The Social Science Journal, 38, 233-250. [ Links ]

Lorenzini, P., Ceroni, G., De Urresti, A., Gutiérrez, H., Gutiérrez, R., Monckeberg, N., Robles, A. & Sepúlveda, A. (2013). Evaluación de la ley 20.348: Resguarda el derecho a la igualdad de remuneraciones. Departamento de Evaluación de la Ley. Recuperado de: http://www.evaluaciondelaley.cl/foro_ciudadano/site/artic/ 20130325/asocfile/20130325153119/informe_ley_nro_20348.pdf [ Links ]

Marín, M., Infante, E. & Rivero, M. (2002). Presiones internas del ámbito laboral y/o familiar como antecedente del conflicto trabajo-familia. Revista de Psicología Social, 17(1), 103-112. [ Links ]

Maruani, M. (1993). La cualificación, una construcción social sexuada. Economía y Sociología del Trabajo, 21-22, 41-50. [ Links ]

Merlano, A. (1983). Motivación y productividad. Revista administración de personal. ACRIP, 3, 31. [ Links ]

Moreno, B., Sanz, A., Rodríguez, A. & Geurts, S. (2009). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del Cuestionario de Interacción Trabajo-Familia (SWING). Psicothema , 21, 331-337. [ Links ]

Organización para la Cooperación y Desarrollo Económicos (OCDE)(2010) Estudio Económico de Chile. Recuperado de https://www.oecd.org/centrodemexico/44493040.pdf [ Links ]

Papí, N. (2005). La conciliación de la vida laboral y familiar como proyecto de calidad de vida desde la igualdad. Revista Española de Sociología, 5, 91-107. [ Links ]

Riquelme, E., Rojas, A., & Jiménez, A. (2012). Perspectivas analíticas sobre la dinámica social. Equilibrio trabajo, familia, apoyo familiar, autoeficacia parental y funcionamiento familiar percibidos por funcionarios públicos de Chile. Trabajo y sociedad, 18, 203-215. [ Links ]

Rubalcava, R. (2001). Evolución del ingreso monetario de los hogares en el período 1977-1994. En: J. Gómez de León. & C. Rabell (Eds.). La población de México. Tendencias y perspectivas sociodemográficas hacia el siglo XXI (pp. 694-724). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERAM) (2003). Análisis de los costos y beneficios de implementar medidas de conciliación de vida laboral y familiar en la empresa. Departamento de Estudios y Estadísticas de SERNAM, 84. Recuperado de: https://estudios.sernam.cl/documentos/?eODYxNjMwAn%C3%A1lisis_de_los_costos_y_beneficios_de_implementar_medidas_de_concliliaci%C3%B3n_de_la_vida_laboral_y_familiar_de_las_empresas. [ Links ]

Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERAM) (2017). Caracterización de Acciones de Buenas Prácticas Laborales con Equidad de Género (BPLEG), desarrolladas en organizaciones públicas y privadas del país. Recuperado de: http://www.biblioteca.digital.gob.cl/bitstream/handle/123456789/3618/SERNAMEG%202017-Estudio%20Caracterizacion%20de%20acciones%20de%20BPL%20con%20equidad%20de%20genero.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Stevens, I. & Van Lamoen, I. (2001). Manual on Gender Mainstreaming at Universtities. ‘Equal Opportunities at Universities. Towards a Gender Mainstreaming Approach’. Garant: Leuven Apeldoorn. [ Links ]

Superintendencia de Seguridad Social. (2017). Riesgo psicosocial en Chile. Resultados de la aplicación del Cuestionario SUSESO/ISTAS21 (2016). Panorama Mensual Seguridad y Salud en el Trabajo, 3(12). Recuperado de: https://www.suseso.cl/607/articles-480616_archivo_01.pdf [ Links ]

Trujillo, M. & Vargas, D. (1996). Categorías motivacionales requeridas para mantener e incrementar la productividad de trabajadores de empresas públicas y privadas de Santa Fe de Bogotá. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Departamento de Psicología, Bogotá [ Links ]

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. A.J.F. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; A.H.R. in b,c,d.

Correspondence: Correspondencia: Andrés Jiménez Figueroa, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Talca. Chile. Avda. Lircay s/n, Talca, Chile. E-Mail: anjimenez@utalca.cl. Agustina Hernández Reveco, Universidad de Talca. E-Mail: agus.hndez.r@gmail.com

How to cite: Jiménez Figueroa, A., & Hernández Reveco, A. (2020). Perception of gender equity and work-family balance in workers belonging to public and private companies in Chile. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2201. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2201

Received: July 26, 2019; Accepted: May 28, 2020

texto en

texto en