Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.2 Montevideo 2020 Epub 21-Mayo-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2202

Original Articles

Individual, contextual and organizational predictors of work engagement and job crafting

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Río Grande del Sur (PUCRS). Brasil

2 Fundación Universidad Federal de Ciencias de la Salud de Porto Alegre (UFCSPA). Brasil jhoanna.altamirano.b@gmail.com, paula.ferreira.rp@gmail.com, br.tocchetto@gmail.com, manoela.ziebell@gmail.com

The purpose of this research was to identify, in a group of motivators, the predictors of engagement at work and job crafting based on the job demand-resources theory with the eight motivational forces model of permanence and turnover. The sample comprised 215 Brazilian workers of the communication and marketing area. The results showed that: a) the individual aspects do not predict engagement at work nor job crafting, b) the contextual aspects (friends expectations and employability) predict in a different way both variables; and finally, c) the organizational aspects (affective identification, growth possibilities, interpersonal relationships and costs associated with leaving the organization) positively predict both engagement at work and job crafting. Considering the benefits of both variables at the individual and organizational level, the study contributes to the literature of the area by highlighting elements that promote them.

Keywords: work engagement; job crafting; organizational behavior; motivation

El propósito de esta investigación fue identificar, en un grupo de motivadores, los predictores de engagement en el trabajo y comportamientos de job crafting con base en la teoría de demandas y recursos laborales junto con el modelo de las ocho fuerzas motivacionales de permanencia y turnover. Integraron la muestra 215 trabajadores brasileños del área de comunicación y marketing. Los resultados mostraron que: a) los aspectos individuales no predicen engagement ni job crafting, b) los aspectos contextuales (expectativas de amigos y empleabilidad) predicen de forma diferenciada ambas variables; y finalmente, c) los aspectos organizacionales (identificación afectiva, posibilidades de crecimiento, relaciones interpersonales y costos asociados a dejar la organización) predicen positivamente tanto engagement como job crafting. Considerando los beneficios de ambas variables a nivel individual y organizacional, el estudio contribuye a la literatura del área al destacar elementos que las promueven.

Palabras clave: engagement laboral; job crafting; comportamiento organizacional; motivación

O objetivo deste estudo foi identificar, a partir de um grupo de motivadores, os preditores de engajamento no trabalho e comportamentos de job crafting com base na teoria de demandas e recursos de trabalho e no modelo das oito forças motivacionais de permanência e turnover. A amostra foi composta por 215 trabalhadores brasileiros da área de comunicação e marketing. Os resultados mostraram que: a) os aspectos individuais não predizem engajamento e job crafting; b) os aspectos contextuais (expectativas de amigos e empregabilidade) predizem de forma diferenciada ambas as variáveis; e por fim, c) os aspectos organizacionais (identificação afetiva, possibilidades de crescimento, relações interpessoais e custos associados a deixar a organização) predizem positivamente tanto engajamento como job crafting. Considerando os benefícios de ambas variáveis em relação aos níveis individual e organizacional, o estudo contribui para a literatura da área ao destacar elementos que as promovem.

Palavras-chave: engajamento no trabalho; job crafting; comportamento organizacional; motivação

The world of work is constantly changing. This change is reflected in the internal work dynamics and in the way in which people understand and direct their own careers, giving more value to positive experiences, prioritizing individual goals and seeking a healthy and satisfying work life. Thus, careers are no longer determined solely by organizational demands, but also by people's goals (Demerouti, 2014). If productivity was previously the focus of management, in the past years more companies have invested in human resource management actions, such as feedback exercises, engagement in decision-making, leader's support and facilitation for a variety of tasks (Bakker & Schaufeli, 2008).

Accordingly, therefore, organizations face difficulties in both recruiting and retaining employees (Oliveira, Beria, & Gomes, 2016). It shows the organization’s inability to manage the human factor and the individuals demands, while attending business objectives. In contrast, workers feel increasingly challenged by the demands of their corporations (Bakker & Demerouti, 2016), which expect high levels of productivity and value other capabilities such as flexibility, teamwork, commitment, proactivity and constant learning (Bakker & Schaufeli, 2008; Hakanen, Peeters, & Schaufeli, 2017).

The communication field is a clear example of this problem. Large marketing and advertising companies have been facing a migration movement of their workers, mainly the younger ones, to other business models related to entrepreneurship (Carvalho, Alves & Machado, 2016). Encouraged by the constant changes in the market, communication workers look not only for a job, but also for a space to meet their needs as professionals and individuals (Carvalho et al., 2016). For this reason, communication is no longer an area that has a low historical level of attention to human capital, now it begins to be an area that looks at the new demands of the communication’s professionals (Carvalho & Christofoli, 2015).

The complexity of these phenomena requires an analysis focused on experiences, individual characteristics and positive aspects, differentiating it from the traditional psychological paradigm and exploring the qualities related to the human being in the organizational environment. Because of it we delve into this work dynamic since the perspective of the job demands-resources theory (DRL; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001). This theoretical model suggests that every work characteristic can be divided into two categories: labor demands and labor resources. The processes of motivation and job deterioration occur through the interaction of these two categories along with personal resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). Additionally, the theory proposes that the relationship between work characteristics and workers' health and well-being influence each other over time (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

One of the most investigated indicators of individual well-being in the job demands-resources theory is engagement (Bakker, Demerouti & Sanz-Vergel, 2014), due to its positive impact for both organizations and workers (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter & Taris, 2008). Engagement is defined as the job-related positive mental satisfaction state characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). It is when an individual has high levels of energy and mental resilience and shows a willingness to invest efforts in his own work and a willingness to persist when facing difficulties. Engagement can also be described as when the individual gets strongly involved with his own activities and find them meaningful, feeling excited and inspired by the work, reaching states of complete concentration and absorption (Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, 2016). This state is related to several positive organizational results. Workers with more engagement are more innovative (Hakanen, Perhoniemi, & Toppinen-Tammer, 2008), they experience a better fit in relation to their jobs (Lascbinger, Wong, & Greco, 2006), they have high levels of performance (Bakker & Bal, 2010), they are more creative (Bakker & Xanthopoulou, 2013) and they show organizational citizenship behaviors (Rich, Lepine, & Crawford, 2010). Engagement is also important as it can promote well-being and health (Airila et al., 2014; Hakanen & Schaufeli, 2012). Studies also show that engagement is associated with proactive behaviors (Macey & Schneider, 2008), since it is a motivational well-being state with high energy levels (Salanova, Schaufeli, Xanthopoulou & Bakker, 2010), it is intrinsically related to the adoption of self-directed behaviors. Thus, numerous studies have already focused on the relationship of this variable with job crafting (Bakker, Rodríguez-Muñoz, & Sanz-Vergel, 2016; Demerouti, 2014).

Job crafting is a Wrzesniewski and Dutton's (2001) term to define physical and cognitive changes of individual’s own initiative where individuals modify their jobs in order to align it with their own abilities, needs and preferences. According to the job demands-resources theory, four types of job crafting are distinguished: increase in structural resources (look for ways to develop oneself as a professional or try to learn new things), increase in social resources (request feedback on self-performance to both colleagues and supervisors), increase in challenging demands (engaging voluntarily in new projects or tasks) and reduction of disruptive demands (avoiding or eliminating contact with mentally or emotionally draining situations). The first three types can be classified as expansive job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), while the latter should be considered closer to a coping strategy (Hakanen, Peeters & Schaufeli, 2017). This is due to some labor demands that have only negative impacts on workers, therefore the reduction of these hindering demands is a mechanism to protect the health of the worker himself (Demerouti, 2014). Therefore, job crafting is a type of bottom-up work redesign, which should be considered a complementary alternative to top-down approaches (Demerouti, 2014) since it increases the number of labor resources and it impacts the general well-being of workers (Tims, Bakker & Derks, 2013). This organizational behavior is also related to the increase in performance (Demerouti, Bakker, & Gevers, 2015), it allows individuals to resignify their jobs and to increase their probability of establishing better relationships, while achieving their individual goals (Slemp & Vella -Brodrik, 2014). The present study will no longer delve into the already well-established relationship between engagement and job crafting (Demerouti, 2014), instead we will focus on identifying what factors predict them independently.

In addition to the approaches of individual qualities and positive aspects within the work domain, the phenomena of turnover have been prompting managers and researchers to ask themselves for what reasons workers remain or leave their jobs (Holtom, Mitchell, Lee & Eberly, 2008). One of the studies representing these theoretical efforts resulted in Maertz & Griffeth's (2004) model of the eight motivational forces for permanence and turnover. This comprehensive model considers aspects of three levels: individual, contextual and organizational, translated into motivational forces (moral, normative, alternative, affective, calculative, contractual, constituent and behavioral).

One of the individual aspects considered in the model is moral strength, which is the favorable or unfavorable values and beliefs about leaving and / or staying in the organization (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004). Although no literature was found directly relating these beliefs to engagement or job crafting, we can assume that both (state and behavior) can be influenced by individual values, which play a fundamental role in shaping goals and behaviors (Shin & Zhou, 2003). Therefore, hypotheses 1 and 2 are:

Hypothesis 1: Moral forces, a) pro-bonds and b) pro-turnover positively and negatively predict Engagement.

Hypothesis 2: Moral forces, a) pro-bonds and b) pro-turnover positively and negatively predict Job crafting.

Contextual aspects are determined by normative and alternative forces. The normative force shows how the individual himself perceives the expectations of people outside his work (family and friends) on his continuity in the current organization (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004). Despite the various investigations on the positive effects of work engagement, its relationship with the individual family aspects is still poorly addressed (Culbertson, Mills & Fullagar, 2012) as well as its relationship with other nearby circles. On the other hand, the alternative force is a reflection of the interaction between one's perceived ability to find a new job and the perception one has about the current market (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004; Oliveira et al., 2016). Regarding perceived employability, the literature shows that feeling capable of acquiring new work alternatives increases the sense of well-being and the perception of objective and subjective success (Guest & Rodrigues, 2015). Therefore, the following hypotheses are established:

Hypothesis 3: The a) normative force negatively predicts Engagement and the b) alternative force predicts it positively.

Hypothesis 4: The a) normative force negatively predicts Job crafting and the b) alternative force predicts it positively.

Finally, the model of reasons for permanence and turnover also includes organizational aspects. Maertz & Griffeth (2004) categorize these aspects into five forces: a) affective, it is a motivational trend that implies positive emotions generated by the organization and by being part of it. It takes into account that an emotional response will be generated by what the worker thinks about the organization; b) calculative, it involves the worker's rational evaluation of the development possibilities inside the organization; c) contractual, it includes the perceptions about what the organization owes to the worker and conversely what the worker owes to the organization, where the sense of obligation to stay is a response to questions related to the psychological contract stipulated at the beginning of the labor bond; d) constituent, it deals with the quality of the worker relationships with leaders and coworkers; e) behavioral, it expresses the associated costs perceived on leaving the current organization.

Previous studies show that several aspects related to these forces above, such as social support, control over one's work, learning opportunity and performance feedback, have positive effects on work engagement (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, 2008). Similarly, the expectations generated by implicit and explicit conditions of labor contracts can generate feelings of violation since the individual will expect fair treatment and mutuality (Rios, Lula, Amaral, & Bastos, 2014). Consecutively, some studies identify organizational climate (Scott & Bruce, 1994), interpersonal relationships (Janssen, Van de Vliert & West, 2004) and job characteristics (Oldhman & Cummings, 1996) as important antecedents of innovative behaviors. Although job crafting is a different concept, recent studies suggest that workers modify their jobs according to their perceptions of themselves (Hakanen et al., 2017). Therefore, the following hypotheses are established:

Hypothesis 5: The a) affective, b) calculative, c) constituent and d) behavioral forces and e) the compliance component of the contractual force positively predicts Engagement, while the f) non-compliance component of the contractual force predicts it negatively.

Hypothesis 6: The a) affective, b) calculative, c) constituent and d) behavioral forces and the e) compliance component of the contractual force positively predict Job crafting, while the f) non-compliance component of the contractual force predicts it negatively.

In this context of constant changes, where the retention of the human factor and the promotion of positive aspects become the main focus of interest for both professionals and academics, it is necessary to understand which specific situations have the potential to stimulate or promote job engagement and job crafting behaviors. The present study aims to explore which individual, contextual and organizational aspects influence engagement and job crafting.

Method

Participants and procedures

The final sample was 215 Brazilian workers from Porto Alegre of the communication and marketing area. The mean age was 32.1 years (SD = 8.71) and 61.4% were women. Regarding the length of stay in the organization, 56.7% of the participants were working in the organization under two years, 26.5% between two and five years and eleven months, and 16.7% over six years. 55.3% had university degrees, 26% had regular basic education and 18.6% had specialization or postgraduate degrees.

The researchers contacted nine communication and marketing agencies through the region's union. During meetings with the human resources area of each agency, the goals of the study were explained, and a permission was requested in order to collect information. Six of these institutions agreed to participate in the study. Then, meetings were held with collaborators to present the research, to answer questions and to explain the data collection process. The online questionnaire was disclosed via email and it contained the informed consent form. The consent form included information on the confidential and voluntary nature of the study as well as a brief explanation of its objectives, procedures and inclusion criteria (to work as a dependent at the time of collection, to belong to the communication and / or advertising area and to be at least 18 years old). The participants had to indicate their agreement by checking the "I accept" option in the consent form to be part of the study. Invitations were sent to 385 workers between June and October 2017, and 215 were answered satisfactorily, reaching a response rate of 55.8%.

Materials

Engagement was evaluated with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, Portuguese adapted version by Vazquez, Magnan, Pacico, Hutz e Schaufeli (2015), which assesses the general state of mind of satisfaction and positive disposition characterized by vigor, dedication and concentration (i.e. In my work I feel full of energy). A questionnaire with 17 affirmative sentences, where the answers were on a likert scale of seven points ranging from zero (never) to six (always). The highest scores indicate higher levels of engagement. In the Brazilian adapted study, the Brazilian sample had an internal consistency of α = 0.95 and in the present study the internal consistency was α = .94.

Job crafting was evaluated with the Work Redesign Behavior Scale, a Portuguese adapted version by Chinelato, Ferreira & Valentini (2015), which assesses the self-initiated behaviors to modify work to increase structural resources (i.e. I try to learn new things), social resources (I ask others for my performance feedback) and challenging demands resources (When an interesting project appears, I offer myself as a participant of it). Questionnaire with 14 affirmative sentences, the answers were in a five-point likert scale from one (never) to five (always). The highest scores indicated more job crafting behaviors. The brazilian adapted study had internal consistency results of α = .71 for an increase in structural resources, α = .78 for an increase in social resources and α = .77 for an increase in challenging demands. In the present sample, the internal consistencies were α = .86, α = .79 and α = .77 respectively.

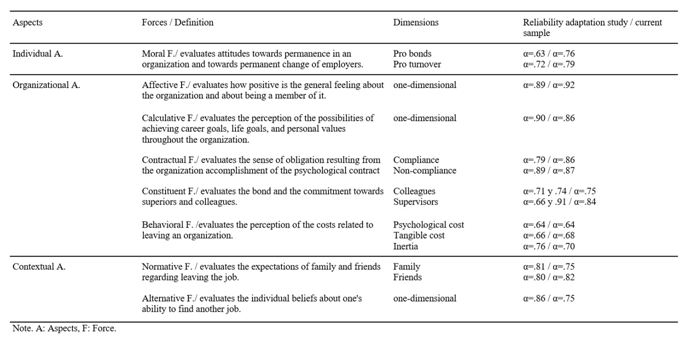

The individual, organizational and contextual aspects were evaluated with the Turnover and Permanence Motivations Inventory, adapted to Portuguese by Oliveira et al. (2016). Inventory with 88 items in a likert scale ranging from one (totally disagree) to five (totally agree). The 88 items reflect eight motivational forces to stay or leave the current organization. These eight forces are operationalized through 14 dimensions, as detailed in Table 1.

Previous research suggests that age, educational level, hierarchy, and permanence time in the organization are related to our study variables (Berdicchia, Nicolli & Masino, 2016; Petrou, Demerouti & Schaufeli, 2015; Vasquez et al., 2015; Yim, Choi & Park, 2015). Thus, in the present study questions concerning these points were incorporated in a sociodemographic questionnaire prior to the presentation of the scales.

Analysis

The data was analyzed in two stages. Pearson's correlation analysis was first performed between engagement, job crafting (increase in structural resources, increase in social resources and increase in challenging demands), the reasons for permanence and turnover (motivational forces categorized in individual, organizational and contextual aspects) and the sociodemographic variables (age, educational level, hierarchy and permanence time). Then hierarchical regressions were performed controlling for the effect of sociodemographic variables and the inclusion of predictors was performed independently for engagement and job crafting through the step-by-step method.

Ethical considerations

The detailed procedures were contemplated within the research with human beings’ ethical standards provided by the Brazilian National Health Council Resolution No. 510/2016. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) with CAAE: 66476517.7.0000.5336.

Results

Preliminary results

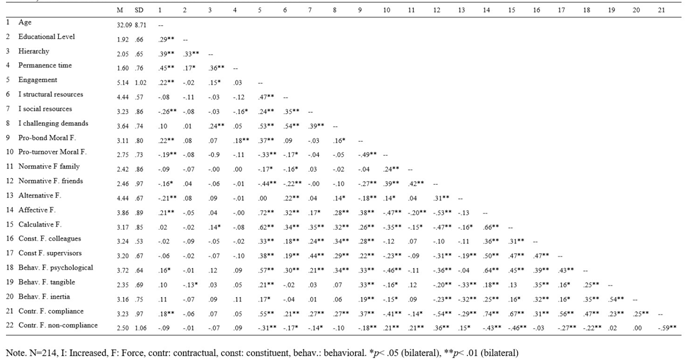

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations and the correlations between the variables. These results confirm the positive association between engagement and all dimensions of job crafting (increase in structural resources: r = .47, p <.01, increase in social resources: r = .24, p <.01 and increase in challenging demands: r = .53, p <.01). Likewise, the correlations in Table 2 provide preliminary support for the hypotheses presented.

Hypotheses confirmation

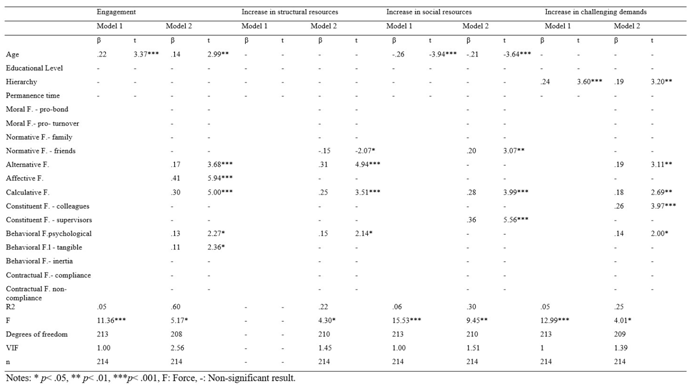

Table 3 shows the regression models used to verify the prediction hypotheses. In the first step (Model 1), the sociodemographic variables (age, educational level, hierarchy, and permanence time) were included to control their effect on the dependent variables. Age showed to be significantly associated with engagement and with an increase in social resources. The hierarchy level achieved significant results only in relation to the increase in challenging demands. Both educational level and permanence time did not achieve significant results with any of the dependent variables. In the second step (Model 2), the independent variables (individual, contextual and organizational aspects) were added, following the step-by-step method.

Regression analysis showed that individual aspects did not predict engagement or job crafting when controlling for the effect of sociodemographic variables. For this reason, hypotheses 1 and 2 were rejected.

Likewise, the regressions showed that the alternative force positively and significantly predicts engagement (β = .17, p <.001), so hypothesis 3 is partially accepted. In the same way, hypothesis 4 is partially accepted since the friend dimension of the normative force predicts the increase in structural and social resources (β = -.15, p <.05 and β = .20, p <.01, respectively), and the alternative force positively predicts the increase in structural resources and challenging demands (β = .31, p <.001 and β = .19, p <.01, respectively).

Finally, regarding hypotheses 5 and 6, the results significantly showed that affective forces (β = .41, p <.001), calculative forces (β = .30, p <.001), psychological behavioral forces (β = .13, p <.05) and tangible forces (β = .11, p <.05) positively predict engagement. So, hypothesis 5 is partially accepted. On hypothesis 6, the calculative forces (β = .25, p <.001, β = .28, p <.001 and β = .18, p <.01 for increase in structural resources, increase in social resources and increase in challenging demands respectively), constituent-colleagues (β = .26, p <.001 for increase in challenging demands), constituent-supervisors (β = .36, p <.001 for increase in social resources) and behavioral-psychological (β = .15, p <.05 and β = .14, p <.05 for increase in structural resources and increase in challenging demands respectively) showed significant prediction results for job crafting. So, hypothesis 6 is partially accepted.

Discussion

The main goal of the present study was to explore which individual, contextual and organizational aspects influence engagement and job crafting, based on the definitions of the job demands-resources theory (Demerouti et al., 2001) in combination with the Maertz & Griffeth’ (2004) model of motivational forces for permanence and turnover. Our results strengthen the idea that there are contextual situations, in addition to the traditionally associated organizational ones, that impact on positive results within companies. Below we discuss the study results in greater detail.

Sociodemographic variables effect on engagement and job crafting

For the purposes of the present study, the effects of age, educational level, hierarchy and permanence time in the company were controlled. Several studies (Berdicchia, Nicolli & Masino, 2016; Petrou et al., 2015; Vasquez et al., 2015; Yim, Choi & Park, 2015) and theories in the field of organizational psychology refer to the relationship between aspects as age, educational level, hierarchy and permanence time and our variables.

Age had a positive effect on work engagement as reported by Vasquez et al. (2015) who found that the older the worker, the higher the levels of engagement. Likewise, the negative effect of age on the increase in social resources of job crafting was evident. That is, as people get older, fewer efforts are directed towards seeking social support and feedback. This reduction reinforces what was suggested by Kanfer and Ackerman (2004), who noted that younger workers compared to older workers are learning-oriented, which could explain their greater inclination to this type of job crafting. Kooij, Tims, & Kanfer (2015) also mentioned that older workers prefer social interactions that affirm their competencies to interactions that offer them future career development opportunities.

The hierarchy had a positive effect on the increase in challenging job crafting demands. As you become more senior, you will invest more in actions geared towards this type of job crafting. This result is in line with findings on the positive association between job crafting oriented to the extension of tasks with degrees of autonomy (Petrou, Demerouti & Xanthopoulou, 2016).

It is important to note that the variables of educational level and permanence time in the organization did not achieve significant results with any of the variables under study here. This suggests that all people, regardless of academic resources or the time they have within an organization, can actively modify their work environments to more satisfying spaces with greater personal significance.

Contextual predictors

The alternative force, within the contextual aspects, positively predicted both engagement and job crafting. This measure, although it is a reflection of self-efficacy regarding one's own ability to get a new job, is subject to our perception of the labor market in which we are immersed (Oliveira et al., 2016). The results reinforce the position that an employable professional does not specifically seek new alternatives, but on the opposite, it contributes to their own sense of success and job satisfaction (Guest & Rodrigues, 2015). On the other hand, according to the conservation of resources theory, by investing one’s own resources (job crafting ways) in increasing employability, the individual reduces the risk of becoming unemployed, while increasing the possibility of get a better job with better opportunities for learning and growth, which ultimately improves their state of engagement and leads to a spiral of profit (Salanova et al., 2010). Similarly, regarding engagement, the results are related to what was found by Schaufeli, Dijkstra and Vázquez (2013), who reported positive association between self-efficacy and affective well-being at work.

The normative force, specifically the dimension that refers to friends outside the organization, had significant potential to predict the increase in structural and social resources. Thus, as the worker perceives that their friendship environment, external to the organization, does not agree with his continuity in their current work, he will invest less effort in increasing his structural resources (that is, learning new things, engaging in new projects). And on the opposite, he will seek to increase his social resources (that is, search for social support and feedback) to compensate for the missing support from his external friends with new internal networks.

Organizational predictors

Four out of five organizational aspects evaluated here obtained significant results as predictors of engagement and job crafting. This supports Macey and Schneider's (2008) finds that the positive experience involved in feeling engaged has the work configuration as a background. Regarding job crafting, Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001) also point out that it is not enough to provide opportunities to promote these behaviors. This as a whole, also strengthens what is proposed in the Hackman and Oldman's (1975) model of the post characteristics. Organizations can act on various aspects of the work to encourage resignification of it, to encourage the employees to take responsibility for the organization objectives and other positive phenomena.

The affective force, which reflects positive feelings of comfort or pleasure towards the organization, has engagement increasing as a logical trigger. Indeed, it effectively showed predictive power. As Schaufeli and Bakker (2010) mentioned, engagement has a connotation that refers to involvement, commitment, passion, focus and energy, which implicitly refers to positive affection and well-being. Salanova et al. (2010) mentioned that workers in the state of engagement consider that they are in pleasant situations, even if they must deal with job challenges and demands.

The calculative force, that is the perception of opportunities to achieve professional life goals through the organization, was a predictor aspect of both engagement and all dimensions of job crafting. The results show that if the evaluation on development or growth is positive, individuals will feel more engaged and they will invest forces and energies to get involved in learning new things, in seeking feedback and in emerging projects (increased structural, social and challenging demands). In this regard, Baruch (2006) mentions that organizations cease to signify control over people’s professional development to become support and development itself, as a way to enable the success of their workers.

The constituent force, that is, the quality of the relationships maintained in the labor context, was a predictor of job crafting in increasing social resources and in increasing challenging demands. Positive relationships with coworkers stimulate the increase in challenging demands, while the positive relationship with the boss or supervisor impacts the increase in social resources. These results show that interpersonal relationships affect the way in which individuals alter their working conditions. People in general invest their resources in maintaining or improving their supportive relationships (Allen, Shore & Griffeth, 2003). This explains that in workplaces where positive interpersonal relationships exist, people engage in job crafting ways that imply contact with others. On the other hand, Parker, Willliams and Turner (2006) study shows that feeling confidence in coworkers leads people to engage in proactive behaviors. This leads us to infer that in spaces where interpersonal relationships are negative, there is less orientation to engage through one's own initiative in redesigning behaviors at work.

Finally, the behavioral force proved to be significantly important in predicting both engagement and two forms of job crafting (increased structural resources and challenging demands). These behavioral forces, specifically the psychological and the tangible, refer to the desire to avoid the psychological and explicit cost that is associated with the withdrawal from the organization (Oliveira, 2016). It is possible that in the face of the economic crisis and the small number of communication agencies in the city where the study was conducted, the participants have perceived that leaving the organization would imply great losses. This perception would lead to higher levels of engagement and job crafting, especially activities capable of making work more interesting and challenging.

It is clear then that the affective aspects, the possibilities of growth, the interpersonal relationships and the costs associated with the work loss are not only important as promoters of job satisfaction, and the motivation related to it, as widely stated in Herzberg and McClelland's models of work motivation in the classical organizational literature, but also generate phenomena with high energy loads and action orientation such as engagement and job crafting.

Individual predictors

The eight motivational forces for permanence and turnover model (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004) considers moral force as a reflection of how the individual values the constant change among employers (Oliveira et al., 2016). The possibility that this moral value could impact on the engagement state or job crafting behaviors was evaluated. However, in none of the regression models the moral force represented important variables for the explanation of these phenomena.

Theoretical and practical implications

This study contributes and expands research on engagement and job crafting in four ways. First, it extends the literature on these variables and their relationship with individual perceptions or motivations in line with Esteves and Lopes (2001) and Petrou et al. (2015) studies. That said, the essence of the eight motivational force’s measure is a reflection of how workers perceive many aspects related to work.

Second, our results show how aspects related to the permanence or departure of workers also impact, in different ways, on the affective state of engagement and on the way in which workers alter their working conditions (job crafting). These findings guide professionals in human resource management on what issues should be addressed in a policy implementation that go beyond passive welfare states such as job satisfaction. Specifically, paying attention to organizational aspects with prediction potential. For example, the analysis showed that having clear professional development plans (reflecting the calculative force) increases levels of work engagement and job crafting behaviors. It will ultimately impact higher levels of performance and it will consequently contribute to business strategy.

Therefore, succession plans as the identification and development of collaborators with high potential and individual dialogues about one's career are good practices that could contribute to the increase of positive states and behaviors at work (engagement and job crafting). Similarly, the incorporation of training and development programs, including job crafting, increases people's confidence and self-efficacy and motivate them to feel more engaged (Anitha, 2014) and to have more tools and resources to invest in behaviors of job crafting.

Third, in close relationship with the above, our results provide valuable information to the area of communication and marketing. This area had our special attention since, as commented by Carvalho et al. (2016), it is perceived as a sector that has been modifying its internal practices in order to attract and maintain its talents. There are still few studies on psychological phenomena in professionals in this area, even though the area has moved more than 15 billion reais in recent years (Sacchitiello, 2019). Taken all together, these factors may be responsible for the frequent experience of overload and stressful work environment (Sarquis & Ikeda, 2007). Therefore, the results obtained must be taken as a picture of the moment that the area is experiencing in order to propose action plans to improve the conditions of its employees. The action plans should focus on the promotion of affective identification in relation to the organization, the promotion and clarification about the possibilities of professional growth, favoring positive interpersonal relationships to promote a work environment that is perceived as undesirable to leave.

Fourth, the present study contributes to the contextualized understanding of these variables at a specific moment in the country (Brazil). Considering that social and economic relationships involve any type of organizational behavior, by focusing on a specific group and market (communication and marketing area) and its particularities, we have a more precise vision of the facts that motivate professionals in this occupational group.

Limitations and future steps

As well as other investigations, the present study contemplates certain limitations. First, since it is a cross-sectional study, its potential for generalization is limited with respect to longitudinal studies. Future research could take measures at different times to understand the real effect of these aspects (individual, contextual and organizational) on engagement and job crafting.

The measures used for the analysis arose from self-report questionnaires, which are affected by the subjectivity of each individual. On the other hand, since the questionnaires were analyzed within an organizational context, their results could be due to an attempt to show the positive aspects of this.

Within the individual aspects, only the values and beliefs about staying or leaving the organization were considered. Future research could investigate in more detail the relationship of engagement and job crafting with other individual aspects such as self-efficacy, proactive personality, resilience at work, among others.

The evaluation of job crafting included only three types (increase in structural resources, in social resources and in challenging demands). The dimension of demands reduction that appears in several evaluations of job crafting did not achieve significant results in the Brazilian study that did the adaptation and validation of the instrument to the Brazilian context (Chinelato et al., 2015). In other words, the brazilian population did not identify expansive job crafting behaviors as belonging to the same group as those focused on reducing demands on their jobs. This phenomenon deserves future research aimed to clarify whether this is due to some context-differentiating dynamics or to the instrument itself. Finally, our study focused on a single occupational area - communication and marketing - which could also limit the generalizability of the results. Therefore, it is suggested to replicate the present investigation to broaden the understanding of the phenomena.

REFERENCES

Airila, A., Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., Luukkonen, R., Punakallio, A., & Lusa, S. (2014). Are job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? The mediating role of work engagement. Work & Stress, 28, 87-105. doi:10.1080/02678373.2013.872208 [ Links ]

Anitha J., (2014). Determinants of employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(3), 308-323. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-01-2013-0008 [ Links ]

Allen, D. G., Shore, L. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (2003). The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process. Journal of Management, 29, 99-118. doi:10.1177/014920630302900107 [ Links ]

Bakker, A.B. & Bal, P.M. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 189-206. doi:10.1348/096317909X402596 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands - resources theory. En: C. Cooper & P. Chen (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (pp. 37-64). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2016). Job Demands-Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. Avance de publicación online. doi:10.1037/ocp0000056 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD-R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 389-411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2016). Modelling job crafting behaviours: Implications for work engagement. Human Relations, 69(1), 169-189. doi:10.1177/0018726715581690 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Positive organizational behavior: engaged employees in flourishing organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 47-g [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22, 187-200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2013). Creativity and charisma among female leaders: The role of resources and work engagement. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24, 2760-2779. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.751438 [ Links ]

Baruch, Y. (2006). Career development in organizations and beyond: Balancing traditional and contemporary viewpoints. Human resource management review, 16(2), 125-138. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.002 [ Links ]

Berdicchia, D., Nicolli, F., & Masino, G. (2016). Job enlargement, job crafting and the moderating role of self-competence. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(2), 318-330. doi:10.1108/JMP-01-2014-0019 [ Links ]

Carvalho, C. M., Alves, D. A., & Machado, A. R. (2016). As novas gerações e o trabalho publicitário. En: E. Freitas, J.A. Saraiva, & G. Haubrich (Eds.), Diálogos Interdisciplinares: Cultura, Comunicação e Diversidade no Contexto Contemporâneo. (pp. 201-213). Nuevo Hamburgo, RS: Feevale. [ Links ]

Carvalho, C. M., & Christofoli, M. P. (2015). O campo publicitário, a agência e a noção de aceleração do tempo: questões iniciais para pensar novos modelos e negócios na prática do mercado publicitário. Sessões do Imaginário, 20(34), 91-99. doi:10.15448/1980-3710.2015.2 [ Links ]

Chinelato, R. S. C., Ferreira, M. C., & Valentini, F. (2015). Evidence of validity of the Job Crafting Behaviors Scale. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 25(62), 325-332. doi:10.1590/1982-43272562201506 [ Links ]

Culbertson, S. S., Mills, M. J., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Work engagement and work-family facilitation: Making homes happier through positive affective spillover. Human Relations , 65(9), 1155-1177. doi:10.1177/0018726712440295 [ Links ]

Demerouti, E. (2014). Design your own job through job crafting. European Psychologist, 19, 237-247. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000188 [ Links ]

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. M. (2015). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87-96. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.001 [ Links ]

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied psychology, 86(3), 499-512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 [ Links ]

Esteves, T., & Lopes, M. P. (2001). Crafting a Calling: The Mediating Role of Calling Between Challenging Job Demands and Turnover Intention. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 34-48. doi:10.1177/0894845316633789 [ Links ]

Guest, D. E. & Rodrigues, R. (2015). Career control. En: A. De Vos & B. Van der Heijden (Eds), Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers (pp. 205-222). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Different types of employee well-being across time and their relationships with job crafting. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. Avance de publicación online . doi:10.1037/ocp0000081 [ Links ]

Hakanen, J.J., Perhoniemi, L., Toppinen-Tammer, S. (2008). Positive gain spirals at work: from job resources to work engagement, personal initiative and work-unit innovativeness. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 73(1), 78-91. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.003 [ Links ]

Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141, 415-424. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.043 [ Links ]

Holtom, B. C., Mitchell, T. R., Lee, T. W., & Eberly, M. B. (2008). Turnover and retention research: A glance at the past, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. Academy of Management Annals, 2, 231-274. doi:10.1080/19416520802211552 [ Links ]

Janssen, O., Van de Vliert, E., & West, M. (2004). The bright and dark sides of individual and group innovation: A Special Issue introduction. Journal of Organizational Behavior , 25, 129-145. doi:10.1002/job.242 [ Links ]

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. The Academy of Management Review, 29, 440-458. [ Links ]

Kooij, D. T., Tims, M., & Kanfer, R. (2015). Successful aging at work: The role of job crafting En: P. Bal, D. Kooij, & D. Rousseau (Eds.) Aging workers and the employee-employer relationship (pp. 145-161). Londres: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08007-9_9 [ Links ]

Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, 3-30. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2007.0002.x [ Links ]

Maertz, C.P. Jr., & Griffeth, R.W. (2004). Eight motivational forces and voluntary turnover: A theoretical synthesis with implications for research. Journal of Management , 30(5), 667-683. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2004.04.001 [ Links ]

Lascbinger, H.K.S., Wong, C.A., Greco, P., 2006. The impact of staff nurse empowerment on person-job fit and work engagement/burnout. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 30(4), 358-367. [ Links ]

Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 607-634. doi:10.2307/256657 [ Links ]

Oliveira, M. Z. D., Beria, F. M., & Gomes, W. B. (2016). Validity Evidence for the Turnover and Attachment Motives Survey (TAMS) in a Brazilian Sample. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) , 26(65), 333-342. doi:10.1590/1982-43272665201604 [ Links ]

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior. Journal of Applied psychology , 91, 636-652. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636 [ Links ]

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E. & Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Job Crafting in Changing Organizations: Antecedents and Implications for Exhaustion and Performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 470-480. doi:10.1037/a0039003 [ Links ]

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2016). Regular Versus Cutback-Related Change: The Role of Employee Job Crafting in Organizational Change Contexts of Different Nature. International Journal of Stress Management. Avance de publicación online. doi:10.1037/str0000033 [ Links ]

Rich, B.L., Lepine, J.A., Crawford, E.R., 2010. Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal , 53(3), 617-635. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988 [ Links ]

Rios, M. C., Lula, A. M., do Amaral, N. D. A., & Bastos, A. V. B. (2014). Contratos psicológicos e comprometimento: o mapeamento cognitivo dos construtos junto a profissionais de RH. Acta Científica. Ciências Humanas, 1(16), 9-24. [ Links ]

Sacchitiello, B. (2019, abril 10). Cenp-Meios: compra de mídia em 2018 foi praticamente igual à de 2017. Meio & Mensagem. Recuperado de https://www.meioemensagem.com.br/home/midia/2019/04/10/mercado-publicitario-movimenta-r-165-bilhoes-em-2018.html [ Links ]

Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W. B., Xanthopoulou, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). The gain spiral of resources and work engagement: Sustaining a positive worklife. En: A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 118-131). New York: Psychology Press [ Links ]

Sarquis, A. B., & Ikeda, A. A. (2007). A prática de posicionamento de marca em agências de comunicação. Revista de Negócios, 12(4), 55-70. [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. En: A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 10-24). Nueva York: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701-716. doi:10.1177/0013164405282471 [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W. B., Dijkstra, P., & Vazquez, A. C. (2013). Engajamento no trabalho. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Shin, S. J., & Zhou, J. (2003). Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal , 46, 703-714. doi:10.2307/30040662 [ Links ]

Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal , 37, 580-607. doi: 10.2307/256701 [ Links ]

Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2014). Optimizing employee mental health: the relationship between intrinsic need satisfaction, job crafting, and employee well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(4), 957-977. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9458-3 [ Links ]

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 18(2), 230-240. doi:10.1037/a0032141 [ Links ]

Vazquez, A. C. S., Magnan, E. D. S., Pacico, J. C., Hutz, C. S., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Adaptation and Validation of the Brazilian Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Psico-USF, 20(2), 207-217. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200202 [ Links ]

Wingerden, J. V., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands-resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 31(3), 686-701. doi:10.1108/JMP-03-2014-0086 [ Links ]

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of management review, 26(2), 179-201. doi:10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011 [ Links ]

Yim, S., Choi, A., & Park, K. (2015). Effects of Employee Value Proposition and Proactive Personality on Job Crafting: South Korean Professional Assistants' CaseInternational Information Institute (Tokyo). Information, 18(11), 4579-4585 [ Links ]

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. J.A. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e ; P.O. b,c,d,e in ; B.S.T in b,c,d,e;M.Z.O. in a,b,c,d,e

Correspondence: Jhoanna Altamirano; PUCRS. Av. Ipiranga, 6681, Prédio 11, Sala 938. CEP 90619-900. Porto Alegre - RS, Brasil. E-mail: jhoanna.altamirano.b@gmail.com. Paula Oviedo, PUCRS. E-mail: paula.ferreira.rp@gmail.com. Bruna Simões Tocchetto, UFCSPA. Calle Sarmento Leite, 245, anexo II, sala 117. CEP 90050-170. Porto Alegre - Rs, Brasil. E-mail: br.tocchetto@gmail.com. Dra. Manoela Ziebell de Oliveira, PUCRS. E-mail: manoela.ziebell@gmail.com

How to cite: Altamirano, J., Oviedo, P., Tocchetto, B.S., & Oliveira, M.Z. (2020). Individual, contextual and organizational predictors of work engagement and job crafting. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(2), e2202. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i2.2202

Received: June 15, 2018; Accepted: May 21, 2020

texto en

texto en