Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.1 Montevideo 2020 Epub 08-Abr-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2150

Original Articles

Analysis of the internal structure of the Character Strengths Scale

1 Programa de Pós Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco. Brasil ana.noronha@usf.edu.br, helder.hvb@gmail.com

Keywords: psychological evaluation; psychometrics; emotions; life satisfaction; psychological tests

Palavras-chave: avaliação psicológica; psicometria; emoções; satisfação com a vida; testes psicológicos

Palabras clave: evaluación psicológica; psicometria; emociones; satisfacción con la vida; pruebas psicológicas

Introduction

The study of character strengths is characterized as an alternative to traditional treatments in psychology that emphasized the psychopathological aspects and the maladjusted characteristics of individuals (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2009). Character strengths are defined as positive characteristics related to human behaviors, thoughts, and feelings that contribute to the development of goodwill and a better life (Park & Peterson, 2006; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). A greater frequency of strengths enables the experience of more positive emotions, better relationships, and greater engagement in activities such as work, studies, among others (Littman-Ovadia, Lavy, & Boiman-Meshita, 2017; Seligman, 2009).

The importance of strengths lies in the fact that they serve as a protective factor against mental illness, allowing people to develop more healthily (Litman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010), minimizing symptoms of anxiety and depression (Rouse et al., 2015), and increasing psychological and subjective well-being (Linley et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2016), as well as emotional self-regulation (Noronha & Batista, 2020). More recently, Noronha and Campos (2018) identified that strengths can be predicted by personality characteristics, such as extraversion and socialization. Furthermore, in relation to parenting styles, understood as a behavioral pattern of relationships between parents and children, character strengths showed greater associations with responsiveness than with demandingness (Noronha & Batista, 2017). In turn, Martínez-Marti and Ruch (2016) found predictive values of strengths in relation to resilience, optimism, life satisfaction, self-esteem, social support, positive affect, and self-efficacy.

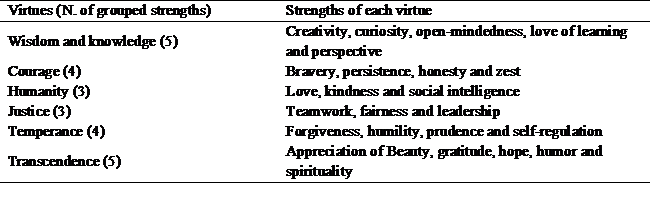

Peterson and Seligman (2004) organized the Values in Action (VIA) classification of Character of Strengths, which includes 24 independent strengths arranged into six virtues, as shown in Table 1. The VIA was developed from extensive research in various cultures, considering legislative, philosophical, and religious texts (Dahlsgaard, Peterson, & Seligman, 2005), which gave rise to the VIA-Inventory Strengths instrument, assuming that the six-dimensional structure was stable over time and across cultures (Brazeau, Teatero, Rawana, Brownlee, & Blanchette, 2012; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

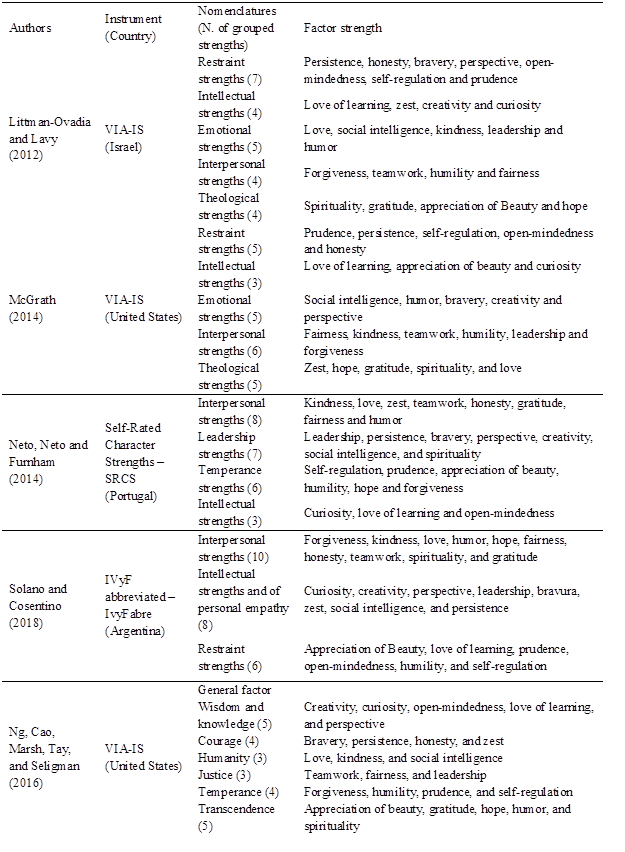

Unlike Peterson and Seligman (2004), some authors believe that the strengths have some degree of interdependence between them (Allan, 2014; Fowers, 2008; Schwartz & Sharpe, 2006). In this regard, it should be noted that the structure with six virtues and 24 strengths proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004) was not replicated empirically (Litman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; McGrath, 2014; Neto, Neto, & Furnham, 2014; Ng, Cao, Marsh, Tay, & Seligman, 2016; Noronha, Dellazana-Zanon, & Zanon, 2015; Solano & Cosentino, 2018). Table 2 shows some factor structures identified in empirical studies. The cultural concerns of each country and the contexts of application are variables considered to justify possible differences in the structures identified for the character strengths (Ciarrochi, Atkins, Hayes, Sahdra, & Parker, 2016); therefore further research on the construct is needed.

In the study developed by Solano and Cosentino (2018), the authors investigated the psychometric properties of an abbreviated strengths scale (abbreviated IVyF) and identified a three-factor structure for the 24 strengths. The factors were called interpersonal strengths, intelligence/personal motivation strengths, and restraint strengths. In turn, McGrath (2014) analyzed a cross-cultural sample, from 16 countries, in order to identify the measurement invariance of different translations of the VIA. The author found a structure of five factors for the VIA, which were named according to the strengths they grouped as: interpersonal, emotional, theological, intellectual, and self-regulation.

The five-factor structure was also observed in the adaptation of the VIA to Hebrew, conducted by Litman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012). Although Neto et al. (2014) found the four-factor factorial solution as the most suitable for the VIA, the nomenclatures are similar to those found by McGrath (2014) and Litman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012), and the strengths were grouped as interpersonal, leadership, temperance, and intellectual strengths. Furthermore, Ng et al. (2016) identified a 2-factor structure for the VIA, in which the general factor was called dispositional positivity, while the specific factors were wisdom, courage, temperance, justice, humanity, and transcendence.

In the Brazilian context, Noronha and Barbosa (2016) developed the Character Strengths Scale (CSS) based on the theoretical assumptions of Peterson and Seligman (2004), but the instrument is not an adaptation of the VIA. In the CSS validation study, Noronha et al. (2015) found a one-dimensional structure that explained 32% of the variance; however they emphasize that the divergences regarding the theoretical model of character strengths should not be an obstacle for researchers to investigate the construct in different samples and with different statistical analyses. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate the factorial structure of the Character Strengths Scale (CSS; Noronha & Barbosa, 2016), using exploratory factorial analyses, since the internal structure of the CSS was not investigated in previous studies.

Method

Participants

Participants included a total of 1500 individuals, aged between 16 and 64 years (M = 23.25; SD = 7.961), being 98.7% (n = 1481) women. They were university students from private institutions of higher education, two in the state of São Paulo and one in the state of Minas Gerais.

Instrument

Character Strengths Scale (CSS; Noronha & Barbosa, 2016). It was based on the Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Three items were designed for each of the 24 character strengths, except for Appreciation of Beauty, which was left with two items, totaling 71 items. They are organized on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me) and have a one-dimensional structure (α = .93; Noronha et al., 2015). Examples of items: ‘I don't hold a grudge if someone mistreats me’ and ‘I think a lot before making a decision’.

Procedures

After data collection was authorized, the project was sent to the Research Ethics Committee of xx, and was approved under number (CAAE: xxx). The instrument was administered in the educational institutions, collectively, after the signing of the Free and Informed Consent Form (FCF), for adults, and the Free and Informed Permission for those who were minors, when authorized by parents, after signing the FCF. On average, 30 minutes were enough to complete the instrument.

Data analysis

The FACTOR software - version 10.5.03 (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006), was used to perform the analyses, for polychoric items, ranging from 0 to 4. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and the Bartlett’s coefficient were considered to identify whether the data matrix was factorable. Parallel analysis (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011), Velicer’s MAP (Minimum Average Partial) (1976), and the Hull’s method (Lorenzo-Seva, Timmerman, & Kiers, 2011) were used for factor retention. The observed fit indices were the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and the Root Mean Square of Residuals (RMSR), in addition to Pearson’s correlation between the factors. Then, exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted using ULS (Unweighted Least Squares) and Promin rotation, to achieve factor simplicity. A minimum value of .30 was established for factor loadings. Items of the same strength with values above .30 in more than one factor were grouped according to the number of items in the factor, the theoretical relevance, and the factor loading value.

Results

Endorsements to items ranged from 1.77 (item 26 - I don’t hold a grudge if someone mistreats me) to 3.44 (item 50 - I think it’s important to help others). Standard deviations ranged from .76 (item 50) to 1.39, for the item “I am patient” (item 12). The possibility of factoring the data matrix was confirmed by KMO, whose coefficient was .93, considered very good. The Bartlett’s sphericity test was estimated at 44058.6 (df = 2485; p < 0.001).

The EFA with ULS extraction method and Promin rotation, chosen as not to delimit, a priori, the interaction between the factors, revealed an initial factor solution of 15 factors with eigenvalues >1.0 which, together, explained 57% of the variance. However, the parallel-based analysis recommended the retention of 10 factors, which did not seem theoretically appropriate given the arrangements of the items. In view of the objective of the study, a structure of 6 factors was requested given the theoretical classification of Peterson and Seligman (2004), with the exclusion of 8 items that did not reach the minimum factor loading of .30 (3, 26, 31, 36, 39, 55, 57, 59). The explained variance was 44.23%, being factor 1 responsible for 22.48%; factor two, 5.40%; factor three, 5.05%, factor four, 4.42%; factor five, 3.84%, and factor six, for 3.04%.

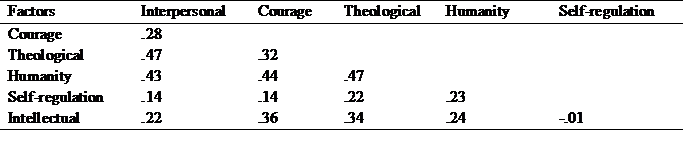

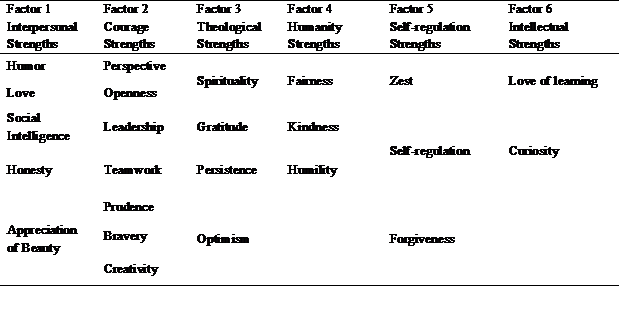

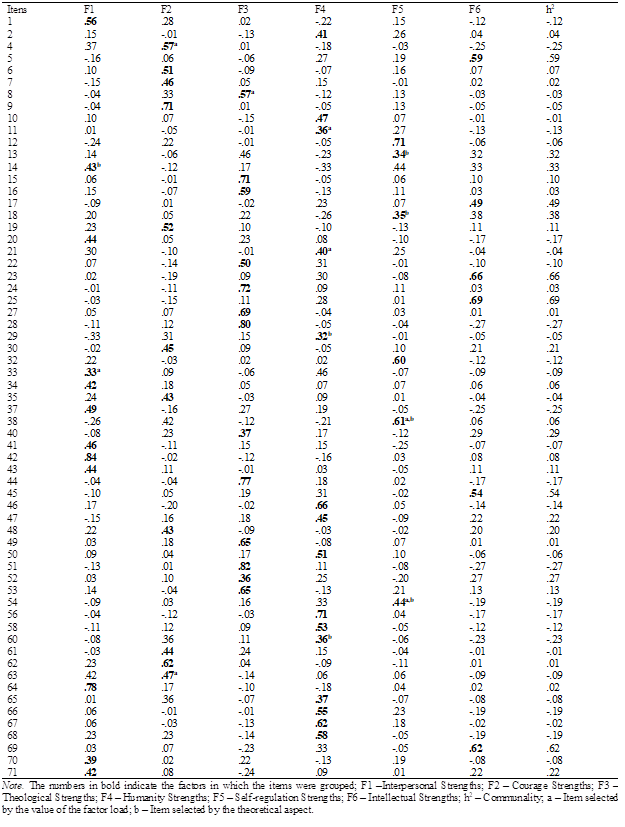

As for the fit indices, the RMSR, a descriptive measure of the mean magnitude of the residual correlations, was .05, therefore acceptable for the 6-factor model. In turn, the GFI was of .97, considered an excellent fit. Precision was estimated using the alpha coefficient, based on polychoric correlations being .89 for factor 1 (12 items); 0.88 for factor 2 (12 items); 0.93 for factor 3 (12 items); 0.91 for factor 4 (14 items); 0.83 for factor 5 (7 items), and 0.88 for factor 6 (6 items). Factor 1 included strengths that refer to relationships with others and was called “interpersonal”. Factor 2 was called “courage”, since it gathered coping strengths. Factor 3 grouped transcendence strengths and was named “theological”. Factor 4 was named “humanity” because it grouped strengths that indicate egalitarian and kind relationships. Factor 5 was called “self-regulation,” once it gathered self-control strengths. Finally, factor 6 was named ‘intellectual’ for gathering learning strengths. Finally, regarding the correlations between the factors, Table 3 presents the information. The correlations and all other parameters are derived from the polychoric correlations matrix, but that are, in the final solution, bivariate correlations between the factors.

The moderate coefficients were found between factors 3 and 1; 4 and 1; 4 and 2; and 4 and 3. Table 4 informs the factor structure and the respective loadings.

Table 4: Factor Loadings (>0.30) and Communalities (h 2 ) values of the Character Strengths Scale (Loading Matrix) - FACTOR

In 15 items, loadings were observed on two factors and the decision was to respect retention of the factor that had higher loading, after theoretical analysis of relevance.

Discussions

The present manuscript intended to investigate the factor structure of the Strengths Scale (Noronha & Barbosa, 2016). The suggestion of the factor retention methods, with ten or 15 factors for the CSS, was not identified in previous studies on character strengths (Litman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; McGrath, 2014; Neto, Neto, & Furnham, 2014; Ng, Cao, Marsh, Tay, & Seligman, 2016; Noronha, Dellazana-Zanon, & Zanon, 2015; Solano & Cosentino, 2018). Thus, we considered the classification proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004), the Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Strengths, prepared by the authors based on extensive literature review, and the result of five years of research, conducted by a team of approximately 40 researchers, as reported by Waters and White (2015). The VIA organizes 24 character strengths, defined as positive, relatively stable psychological characteristics, translated into an analogy as psychological ingredients that lead people to seek the good for themselves, for others, and for society (Park & Peterson, 2006, 2009; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The instrument used in this study (CSS) was built based on the VIA (Noronha & Barbosa, 2016) and had its internal structure initially studied by Noronha et al. (2015). The investigation, with second order analyses, resulted in a better fit for the one-factor solution, not confirming the theoretical structure of Peterson and Seligman (2004), with six virtues and 24 strengths.

Previously, validity studies were conducted based on the relationship with other variables, such as personality and parental styles (Noronha & Batista, 2017; Noronha & Campos, 2018). The personality traits Extraversion and Socialization were the ones that most predicted character strengths (Noronha & Campos, 2018). In relation to parenting styles, the strengths presented higher magnitudes of correlation with responsiveness, which in turn translates affection, involves sensitivity, acceptance, and commitment (Noronha & Batista, 2017).

As for the findings of the present study, the final version consisted of 63 items. Factor 1 included the items of the strengths Humor, Love, Social Intelligence, Honesty, and Appreciation of Beauty. Factor 2 included Perspective, Openness, Leadership, Teamwork, Prudence, Bravery and Creativity. The strengths Spirituality, Gratitude, Persistence, and Optimism were organized in factor 3. Factor 4 included Impartiality, Kindness, and Humility. Factor 5 included Zest, Self-regulation and Forgiveness, and, finally, factor 6, included Love for Learning and Curiosity. To facilitate the visualization of the results, Table 5 shows the strengths by factor.

Ng et al. (2016) tried to replicate the theoretical structure of the VIA, using a large database with more than 400 thousand participants who responded electronically to the instrument. However, although they have reasonably arrived at a similar structure, it should be noted that more than half of the 240 items were excluded, with the instrument remaining with 107. In addition, a general factor was found, in which 30 items loaded more heavily on it than on the specific factor.

In the present study, the first factor found has the relationship with others as its central nucleus, showing lightness and achieving a joyful vision of adversity (Humor), establishing two-way relationships (Love), ease of interactions (Social Intelligence), and taking responsibility for feelings and actions (Honesty). Possibly, what distances it from this nucleus is Appreciation of Beauty; however, it adds beauty, which can be found in everyday life. Solano and Cosentino (2018) also identified that the strengths Humor, Love, and Honesty were grouped in the same factor, called interpersonal strengths.

Factor 2 deals with characteristics of coping, decision, or the pursuit of goals. There is a block referring to the relationship with others, such as providing wise advice (Perspective), teamwork (Sense of collectivity), and encouraging a group (Leadership), and another referring to a movement of the individual him/herself, such as allowing a change of mind (open-mindedness) and new and productive thinking (Creativity), reflecting on one’s choices (Prudence), or not being afraid of challenges (Bravery).

The third factor was the one that best replicated the model by Peterson and Seligman (2004), for including three strengths out of the five theoretically predicted for the virtue of transcendence, which concerns connections to the universe and meaningfulness. Persistence, a strength that originally accompanies the virtue of courage, could contribute in this block with the conviction that it must be present in the face of difficulties. In this regard, there is relevance when one takes optimism as a reference, since it is shaped by goals and expectations. Similar results were found by Littman-Ovadia and Lavy (2012), except for the non-inclusion of Persistence.

Factor 4 can be called Humanity, especially due to the presence of Kindness and Humility, although only Kindness is included in the virtue suggested by the VIA (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Allied to this is Fairness, which reveals equal treatment to everyone and the sense of equity and justice. The factor called Interpersonal by McGrath (2014) included the same three strengths of this study, adding also Forgiveness and Leadership.

The three strengths that make up Factor 5 show coherence. Forgiving others and not being revengeful (Forgiveness) and having control over one’s emotions (self-regulation) compose the virtue of temperance, which values the control of excesses. In another measure, Zest refers to vital energy and has been an important marker of mental health for its negative relationships with depression (Rouse et al., 2015). Self-regulation (SR), as highlighted by Berking, Wirtz, Svaldi, and Hofmann (2014), can also be an important protective factor for depression, which was corroborated by the findings of Weiss, Gratz, and Lavender (2015), who investigated significant and low associations between SR, generalized expectation for regulation of negative mood, and difficulty in emotional regulation and non-acceptance of emotion.

Finally, the sixth factor added two strengths, Love for learning and Curiosity, which is partially in line with the findings of Neto et al. (2014), which included in the group of Intellectual Strengths, Curiosity and Love for Learning, besides Open-mindedness. Similarly, in the findings of McGrath (2014), the third strength to compose the factor was Appreciation for Beauty, not Open-mindedness.

Possibly, the differences found between the theoretical model of Peterson and Seligman (2004) and the results of the present study, are explained by the fact that there is some interdependence between the strengths (Fowers, 2008; Schatz & Sharpe, 2006). Allan (2014) mentioned the importance of investigating strengths considering some pairs (for example, honesty and kindness; love and social intelligence), since when isolated, they may be less effective than when used together. The intellectual strengths found in factor 6 are close to the proposition by Allan (2014), once Curiosity indicates interest, search for novelties, and thirst for knowledge, while Love for learning concerns more systematized knowledge, even without external incentives. In other words, having Curiosity without Love for learning can lead the individual to be only interested in something, but without seeking a deepening and, consequently, growth in certain subjects.

Conclusions

The results of this research go in the same direction of other studies, indicating that the theoretical model proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004) has no empirical support. Although a six-factor structure was identified, character strengths were arranged differently in the factors when compared to the original theoretical proposition.

We may consider as limitations of the present study, the fact that no analyses were conducted to indicate the influence of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in the responses to the items, which would minimize some possible scale biases. In this sense, it is important that further studies consider analyses that investigate the differential functioning, acquiescence, social desirability, and discriminatory power of the items in order to better understand such factor arrangements.

REFERENCES

Allan, B. A. (2014). Balance among character strengths and meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(5), 1247-1261. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9557-9 [ Links ]

Berking, M., Wirtz, C. M., Svaldi, J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2014). Emotion Regulation Predicts Symptoms of Depression over Five Years. Behavior Research and Therapy, 57(1), 13-20. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.003 [ Links ]

Brazeau, J. N., Teatero, M. L., Rawana, E. P., Brownlee, K., & Blanchette, L. R. (2012). The Strengths Assessment Inventory: of a New Measure of Psychosocial Strengths for Youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(3), 384-390. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9489-5 [ Links ]

Ciarrochi, J., Atkins, P. W. B., Hayes, L. L., Sahdra, B. K., & Parker, P. (2016). Contextual positive psychology: Policy recommendations for implementing positive psychology into schools. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(1561), 1-16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01561. [ Links ]

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 203-213. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.203 [ Links ]

Fowers, B. J. (2008). From continence to virtue: Recovering goodness, character unity, and character types for positive psychology. Theory & Psychology, 18(5), 629-653. doi:10.1177/0959354308093399 [ Links ]

Linley, P. A., Nielsen, K. M., Wood, A. M., Gillett, R., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). Using Signature Strengths in Pursuit of Goals: Effects on Goal Progress, Need Satisfaction, and Well-being, and Implications for Coaching Psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 5(1), 6-15. Recuperado de http://www.enhancingpeople.com/paginas/master/Bibliografia_MCP/Biblio05/USING%20SIGNATURE%20STRENGTHS%20IN%20PURSUIT%20GOALS.pdf [ Links ]

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2012). Character strengths in Israel Hebrew adaptation of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 41-50. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a00008 [ Links ]

Littman-Ovadia, H., Lavy, S., & Boiman-Meshita, M. (2017). When theory and research collide: examining correlates of signature strengths use at work. Journal of Happiness Studies , 18(2), 527-548. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9739-8 [ Links ]

Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Ferrando, P. J. (2006). FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analyses model. Behavior Research Methods, 38(1), 88-91. doi: 10.3758/BF03192753 [ Links ]

Martínez-Martí, M. L., & Ruch, W. (2016). Character strengths predict resilience over and above positive affect, self-efficacy, optimism, social support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(2), 1-10. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1163403 [ Links ]

McGrath, R. E. (2014). Measurement Invariance in Translations of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment , 32(3), 187-194. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000248 [ Links ]

Neto, J., Neto, F., & Furnham, A. (2014). Gender and Psychological Correlates of Self- rated Strengths Among Youth. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 315-327. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0417-5 [ Links ]

Ng, V., Cao, M., Marsh, H. W., Tay, L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2016). The factor structure of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS): An item-level Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (ESEM) bifactor analysis. Psychological Assessment, 29(8). doi: 10.1037/pas0000396 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Barbosa, A. J. G. (2016). Forças e virtudes: Escala de Forças de Caráter. In C. S. Hutz (Org.), Avaliação em Psicologia Positiva: Técnicas e Medidas (pp. 21-43). São Paulo: CETEPP. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2017). Escala de Forças e Estilos Parentais: Estudo correlacional. Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia, 8(2), 2-19. doi: 10.5433/2236-6407.2017v8n2p02 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2020). Relações entre forças de caráter e autorregulação emocional em universitários brasileiros. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 29(1), 73-86. doi: 10.15446/.v29n1.72960 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Campos, R. R. F. (2018). Relationship between character strengths and personality traits. Estudos de Psicologia, 35(1), 29-37. doi: 10.1590/1982-02752018000100004 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L., & Zanon, C. (2015). Internal structure of the Characters Strengths Scale in Brazil. Psico-USF, 20(2), 229-235. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200204 [ Links ]

Oliveira, C., Nunes, M. F. O., Legal, E. J., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2016). Bem-Estar Subjetivo: estudo de correlação com as Forças de Caráter. Avaliação Psicológica, 15(2), 177-185. doi: 10.15689/ap.2016.1502.06 [ Links ]

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29(6), 891-909. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.011 [ Links ]

Park, N., & Peterson, P. (2009). Character strengths: Research and practice. Journal of College & Character, 10(4). doi: 10.2202/1940-1639.1042 [ Links ]

Peterson, C. E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rouse, P. C., Jet, J. J. C. S., Zanten, V. V., Ntoumanis, N., Metsios, G. S., Yu, C., …, & Duda, J. L. (2015). Measuring the positive psychological well- being of people with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional validation of the subjective vitality scale. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 17(1), 1-7. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0827-7 [ Links ]

Schwartz, B., & Sharpe, K. E. (2006). Practical wisdom: Aristotle meets positive psychology. Journal of Happiness Studies , 7(3), 377-395. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3651-y. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Felicidade autêntica: usando a Psicologia Positiva para a realização permanente. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva. [ Links ]

Solano, A. C., & Cosentino, A. C. (2018). IVyF abreviado -IVyFabre-: análisis psicométrico y de estructura factorial en Argentina. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana/Bogotá (Colombia), 36(3), 619-637. doi: 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.4681 [ Links ]

Timmerman, M. E., & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2011). Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 209-220. doi: 10.1037/a0023353 [ Links ]

Waters, L., & White, M. (2015). Case study of a school wellbeing initiative: Using appreciative inquiry to support positive change. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5(1), 19-32. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v5i1.2 [ Links ]

Weiss, N. H., Gratz, K. L., & Lavender, J. M. (2015). Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification, 39(3), 431-453. doi: 10.1177/0145445514566504 [ Links ]

Financing: This work was carried out with the support of the Coordination for the Improvement of Personnel and Higher Education - Brazil (CAPES) - Financing Code 001

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. A.P.P.N. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; H.H.V.B. in c,d,e.

Correspondence: Ana Paula Porto Noronha. Universidade São Francisco, Campinas-SP. Endereço: Rua Alexandre Rodrigues Barbosa, 45, Itatiba, SP - Brasil, 13251-900. E-mail: ana.noronha@usf.edu.br. Helder Henrique Viana Batista. Universidade São Francisco, Campinas-SP. Endereço: Rua José Augusto de Mattos, 475, Campinas, SP - Brasil, 13060-748. E-mail: helder.hvb@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2020). Analysis of the internal structure of the Character Strengths Scale. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(1), e-2150. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2150

Received: October 22, 2018; Accepted: April 08, 2020

texto em

texto em