Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.14 no.1 Montevideo 2020 Epub 01-Jun-2020

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2107

Artículos Originales

Teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities

1 Depto. de Psicología del Desarrollo y Educacional. Universidad Católica del Uruguay mmbermudez123@gmail.com, inavarre@ucu.edu.uy

Keywords: inclusion; attitudes; inclusive education; primary education; disability

Palabras clave: inclusión; actitudes; educación inclusiva; educación primaria; discapacidad

Palabras-chave: inclusão; atitudes; educação inclusiva; educação primária; deficiência

It is impossible not to consider disabilities as a part of the human condition and that every individual has them to some extent at a given moment in their life, as stipulated by the “Informe mundial sobre la discapacidad (World report on disability)” by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2011).

From that perspective, students with disabilities have a recognized right to be a part of the general education (Verdugo & Rodriguez, 2008). In the past few decades there has been an attempt to unify general and special education into a single educational system, accepting the inefficiency of segregated education. Moreover, some authors hold that:

It was not enough to attempt to integrate the student and assist them in learning different abilities in order to share a space and a curriculum in general education, but it was observed that integration could not take place if environmental aspects were not modified (p.7).

This is how the concept of inclusion was created. The changes identified in educational care for students with disabilities were linked to the ones that occur with the concept of disability: it is no longer regarded as a problem, a disorder or a student’s deficit and context and the interactions happening therein begin to considered.

Legal dispositions don’t change the practice (Sánchez, Borzi & Talou, 2012). It is the teacher can make a difference in the performance of the students, even for those whose performance is expected not to be good. The success or failure of their students is directly related to the teacher’s attitude.

Definition of the issue and objectives

Many researchers have reached the conclusion that the interaction between equals enables learning. However, this does not happen automatically (Elices, Del Caño & Verdugo, 2002). The starting point must be the teaching staff. In this sense, Ainscow (2012) states that the changes in the students depend on the behavior of adults and the expectation they have on their ability to learn. As studied by Romero (2006) committed teachers must always begin by reflecting upon their own tasks, since this will allow them to “make their intentions become purpose and action” (p. 43).

Considering that the legal regulations do not assure the success of the educational inclusion (Verdugo, 2002), and taking into account the importance of the context in the development of the individual, and that teachers are in charge of mediating the two, it seems essential to recognize the attitudes they have toward people with disabilities in order to understand their practices. Studies carried out under the supervision of Verdugo assert the possibility of modifying the attitude toward people with disabilities (Priante, 2003).

The general objective of this study is to recognize the attitudes of the teachers that work for state education in our country with regard to students with disabilities.

The specific objectives are: Describe the personal factors that may determine the attitude of the teachers regarding students with disabilities, and compare the teacher’s attitudes regarding their work context.

Conceptual framework

The concept of disability has taken multiple forms, changing the medical model that considered it an individual problem or a disorder from a biological point of view, (Clasificación Internacional de Deficiencias, Discapacidades y Minusvalías (CIDDM), 1989). The individual was, according to older view, perceived as deficient (Barton, 2011), having to rectify “limitations in their behavior” through medical treatments (Seoane, 2011).

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations Organization (UN), 2006) includes in the definitions of disability those individuals with long term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory shortcomings which may affect their full and effective participation in society, in the same conditions as everyone else, due to the presence of different barriers.

The WHO (2011) defines disabilities as a complex phenomenon that reflects the interaction between the characteristics of the human organism and the features of the society (negative attitudes, inaccessible transport and buildings and limited social support). Nowadays, disabilities are considered a human rights issue.

The biopsychosocial model does not look for a cure in order for the individual to adapt, but for society to offer forms to guarantee the accessibility and inclusion of every individual and it must be carried out through the adoption of public policies (Colamarco & Delamonica, 2013).

With regard to the educational response, López, Echeita and Martín (2009) state that the bureaucrat organization schemes oriented toward a homogenous education for a group of students considered homogenous has limited efficacy. It is possible to consider the process of educational inclusion as a response to the rights (UN, 2006), strengthening the relationship between internal or individual factors and external, social or contextual factors of the disabilities (Seoane, 2011). From there on, certain limitations in the restrictions that are imposed can be seen (Urmeneta, 2010) and there is a belief in the autonomy of the individuals, aware of their limitations and the necessity of services and a support system that facilitates the exercise of their abilities and rights (Seoane, 2011).

There is an attempt to recognize the differences between the students, not seeing them as a threat (Martinis & Redondo, 2006) but considering them as a support resource and not as a problem to resolve (Verdugo & Rodriguez, 2008). The goal is to offer “an education and a school performance that is high quality and strict taking into account the abilities of each student” (Wehmeyer, 2009, p. 107), which attempts to no longer center in the deficiencies and emphasizes the strengths of an common education, while also being adapted and personalized to the individual characteristics (Echeita, 2013).

For Echeita and Ainscow (2011), the identification and the destruction of the barriers that limit the presence, participation and learning experience is necessary, especially for those students who are in a more vulnerable condition. In school life, those barriers are physical but more importantly personal (Echeita, Verdugo, Sandoval, Simón, López, González-Gil & Calvo, 2008 ; Gutiérrez, 2007).

The most relevant proposal with regard to that topic brings to the table the idea of establishing collaboration networks inside and outside of education centers, creating connections between cultures and educational policies and practices (Booth & Ainscow, 2002). Inclusive cultures, according to those authors, refer to the values that guide actions of the community and are manifested in ways that suggest what individuals should do and how they should do it.

The success of inclusion, according to Verdugo (2009), not only requires actions addressing the practices (microsystem), but also organizational changes and innovations in the different educational systems (mesosystem) and in the educational policies (macrosystem). But true changes can only be carried out by those who work with students (Verdugo, 2011).

In the first place, it is essential to understand how human behavior is determined. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action, in order to predict a subject’s behavior, there is nothing more efficient than to ask them directly what their intention is. From this point of view, there is an attempt to analyze the processes that lead from an intention to an action (Reyes, 2007). According to this author, Fishbein and Ajzen (as cited in Reyes, 2007) believe that behavior can be foreseen through beliefs, given that human beings are rational beings who can make use of the information they posses in order to act. Moreover, Novo, Muñoz and Calvo (2011) base their investigation on the same theory, indicating that intentions are a result of the sum of the influences of attitudes and subjective norms.

Based on the cited authors, attitude means a predisposition to respond consistently in a favorable or unfavorable way to objects, people or groups of people and situations. In this way, three types of attitude components have been identified (Catalán & González, 2009; Gargallo, Pérez, Fernández & Jiménez, 2007; Sierra, 1999; Verdugo, 2002). From a cognitive or an ideological point of view, an attitude is supposed to reflect thoughts, ideas, beliefs, opinions and perceptions of an attitudinal object (in other words, how the attitudinal object is defined). Each thought has, moreover, a certain degree of positive or negative emotion associated with it (affective, evaluative, sentimental component), which implies sympathy or antipathy toward things or people. The conduct, behavioral or reactive component implies the predisposition to act, getting closer or further away or going against the object.

The attitudes and the project of the people or groups of individuals allow the educational policies to advance (Perrenoud, 2004). That shows the importance of the engagement of the teachers to carry out changes required by the students, the profession and the school, beyond legal dispositions (Bolivar, 2010).

In a more recent model than the one proposed by López et al. (2009) which is centered in disruptive conducts, Urbina, Simón and Echeita (2011) also considered that the previously mentioned cultures, policies and practices more or less inclusive result from the ideas of the teachers regarding their role.

After checking the investigations carried out on the attitude of the teacher toward people with disabilities, it was found that, in general, they were positive (Araya, González & Cerpa, 2014; Martinez & Bilbao, 2011; Moreno, Rodriguez, Saldaña & Aguilera, 2006), and the same applied to teachers in training (Castaño, 2012, Seva, 2016).

However, according to Baña, Fernández and Fernández (2006), the students do not have the same rights (voting, getting married, having children) or the same opportunities; they are not taught to be autonomous individuals who fully develop; they are discriminated against for being different and, as a consequence, they have a lower quality of life. These authors consider that teachers choose the kind of activity depending on the perception they have of students with disabilities and put an emphasis on the individual’s difficulties and deficiencies. By doing this, when teachers consider that students with disabilities are less intelligent than other people, they are given simple and repetitive tasks with plain instructions and thus they are not able to make use of the help, resources and strategies for their comprehensive development.

With regard to the personal variables that determine the attitude of the teachers toward disabilities, researchers do not offer a unanimous criterion regarding the influence of gender; some consider men have a more favorable attitude than women (Baña et al., 2006) and some have not found any significant differences (Dominguez & López, 2010, García & Alonso, 1985; Moreno et al. 2006) or consider women to be above the average and men, below (Martinez & Bilbao, 2011).

Attitudes turned out to be more positive among younger teachers (García & Alonso, 1985). Thus, Domínguez & López (2010) come to the conclusion that the older the teacher, the lower the importance they give to normative-legislative aspects that frame diversity. The rise in specialization or training seems to improve the attitudes (García & Alonso, 1985; Talou, Borzi, Vázquez, Gómez, Escobar & Hernández (2010)), but there does not seem to be a link between the attitude and the teacher’s work experience (Martínez & Bilbao, 2011).

It matters whether teachers have contact with people with disabilities or not: people with said experience had a more positive attitude (Baña et al., 2006; Castaño, 2012; Martínez & Bilbao, 2011; Moreno et al., 2006; Rodríguez, Álvarez & García, 2014). More positive attitudes toward inclusion were found in initial education and primary school teachers, possibly due to the existence of less academic, more individualized and less strict programs (García & Alonso, 1985); on the contrary, teachers working in more advanced educational stages believe there is an increase in difficulty in class control, self-efficacy and in developing the curriculum (Urbina et al., 2011).

Considering the characteristics of the context that determine the attitudes, García and Alonso (1985) did not find meaningful differences regarding the type of educational center, attributing success of inclusion to specific effort of some teachers, giving the organization a smaller role (Ossa, 2008). Martínez and Bilbao (2011) found similar results.

Given that attitudes are a product of learning (Ovejero, 2007; Verdugo, 2002) and, thus, they are shaped throughout an individual’s whole life, interventions in order to improve every mentioned aspect, as well as in educational contexts, promote integration and changes in ideas (González & Baños, 2012).

Training is one of the possible external aids teachers should receive to remain committed (Bolivar, 2010). As Perrenoud (2004) states, it should be important that teachers participate in the processes of decision and become agents in their own training.

Castaño (2012), in a study on the attitudes of more than a thousand teachers in training, observed that those with more knowledge about disabilities had also more positive attitudes. Seva (2016), while studying the attitudes teachers in training of Infant Education had toward disabilities, finds that those who were in their last year of training showed a higher degree of personal involvement that those who were in their first.

Zeballos (2015), after analyzing the misconceptions related to childhood disability and educational inclusion in the Teaching BA under Plan 2008, within the Uruguayan context, reached similar conclusions. The investigator believes that the differences are related to the teacher’s training background and practices. The training must be continuous and comprehensive, according to what has been proposed by Valenzuela, Guillén, and Campa (2014) and must be applied to all teachers, notwithstanding their workplace. Verdugo (2002) talks about “competence sense” and Baña et al. (2006) of “awareness”. Moreover, Novo, Muñoz, and Calvo (2015) state that the intention to support the inclusion of people with disabilities is affected by the teachers’ perception of their ability to help.

Ten years after the World Convention on Education for All, which constitutes a universal commitment to the access of education, Latin American, Caribbean and North American countries evaluated the progress carried out in the region. Gathered in Santo Domingo -on February 2000-, they committed “to establish legal and institutional frameworks to make inclusion effective and compulsory as a collective responsibility” (UNESCO, 2000, p. 39).

Later, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities approved on December 13, 2006 at the United Nation’s Headquarters, ratified by the Uruguayan State in the year 2008 (Act 18.418), implied a paradigm shift regarding people with disabilities. The Act clarifies and defines the cases where their rights have been violated, where it is necessary to introduce changes to allow them to exert their rights in an effective way and where their protection must be strengthened.

In Uruguay, Act 18.651, in article 40 states “the equality of opportunities for people with disabilities” (Chapter VII), defining them as “every person who suffers from or has a functional alteration (…) which, related to their age and social context, implies considerable disadvantages for their familiar, social, educational or occupational integration” (Chapter I, Article 2). This definition means an improvement given that it diverges from the concept of deficiency that was previously used (Viera & Zeballos, 2014).

In the last few years, there have been programs and devices which have tried to solve inclusion difficulties (Consejo de Educación Inicial y Primaria (CEIP), 2011). Such is the case of Maestros Comunitarios; Maestro más Maestro; Atención Prioritaria en Entornos con Dificultades Estructurales Relativas (from its Spanish initials, A.PR.EN.D.E.R.); Escuelas Disfrutables, and the Proyecto Intersectorial de Atención para el Desarrollo y el Aprendizaje, la Promoción de Derechos y el Fortalecimiento de las Instituciones Educativas (INTER-IN).

Circular no. 58 by CEIP (2014) approved the “Protocolo de inclusión educativa de educación especial (Protocol of educational inclusion for special education)” which stablishes the competence of Special Education to guide and support the inclusion of students with disabilities, optimizing interinstitutional coordination and considering support measures for inclusion (attendance at Common School or double attendance at a Common and a Special school, aids in Special schools, internships at Special schools, itinerant teachers, definition of the access adaptations of the curriculum).

In 2017, the “Protocolo de actuación para la inclusión de personas con discapacidad en centros educativos (Protocol of action for the inclusion of persons with disabilities in educational centers)” was approved, which guides actions in order to support diversity, bring a framework of good practices, details strategies to reach accessibility for all students and mentions the importance of sensitizing and educating teachers (Ministerio de Educación y Cultura (MEC), 2017).

According to the last Population Census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), 2011), 83% of children with disabilities attend common educational centers, while 17% of them attend special education centers. Moreover, 57% of children with disabilities are enrolled in Special Education, while 43% attend common schools (CAinfo, 2013). These conclusions must be treated with caution, given the difficulties that exist for the collection of information and the difficulties which are inherent to the diagnostic of disabilities. The data collected by the Census is based on the self-identification of the people and not on a technical diagnosis. The lack of availability of good quality statistical information on the right of education for children with disabilities in the country should be highlighted (Centro de Archivos y Acceso a la Información Pública (CAinfo), 2013), which shows the low visibility and priority this topic has had within the State.

Among the specific commitments the member States of the UN have taken up to ensure inclusion, there is the adoption of pertinent measures for the training of teachers and other professionals for working with people with disabilities, in every level of teaching (UN, 2006). However, a country’s ratification does not always mean a link between the proposals and the necessary actions (Colamarco & Delamonica, 2013). So much so that the Educational Inclusion is not a part of basic training for teachers in our country (CAinfo, 2013).

In the study plan for teacher training, the approach to inclusive models is only carried out through Learning and Inclusion (Consejo de Formación (CFE), 2017) and of Human Rights (CFE, 2016) Seminars and they do not modify, according to a study by Zevallos (2015), the graduates’ idea, since the number of courses on inclusion is not sufficient.

According to the National Teaching Census (Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP), 2007), the majority of teachers perceive learning difficulties as a problem for their work (87.2%), considering it a serious issue in 40.5% of the cases. Moreover, behavioral problems are perceived as a difficulty by 7 every 10 teachers (71.4%), among which half believe it to be a serious problem (34.5%). It is worth mentioning that children with behavioral problems make up the second biggest group among children with disabilities enrolled in state schools (26%), after learning disabilities (36%) (CAinfo, 2013).

Primary school teachers are the teachers who least take part in seminars, congresses or talks on education or their respective area (41.4%), although information shows an important predisposition among the teaching body toward broadening their training: approximately 3 every 10 teachers are willing to specialize if such training was offered by ANEP.

Notwithstanding the existing regulations, the numeric indicators and the training teachers receive, Uruguay keeps a segregated education system, consequently, change mute arise from institutional actors, directives, teachers and investigators (Viera & Zeballos, 2014). Continuous training and the perception of not having enough time to support diversity in class are essential when defining strategies in order to favor inclusion (Angenscheidt & Navarrete, 2017).

Method

This investigation is descriptive, of a transversal, correlational type (León & Montero, 2004), based on the application of a questionnaire.

Participants

The investigation consists of an analysis of the information obtained from a sample of 42 primary school teachers from state educational centers, located in rural and urban towns of the department of Lavalleja. Those schools are among the second and fifth quintile of sociocultural context (CEIP, 2017). All of them teach fifth and sixth grade in Common Education.

Among them, 42.9% are younger than 40 years old; 57.1% have been teaching for less than 20 years; 21.4% have primary school training. 50% work as teachers for multiple grades and the other 50% work at schools which only have one teacher per grade. 11.9% have worked at special education and 9.5% have taken courses on special education and/or learning difficulties.

78.6% of teachers express having had contact with people with different types of disabilities and 47.6% have children with disabilities in their class.

Instrument

To obtain quantitative data, the scale used was taken from Actitudes hacia las personas con discapacidad (Verdugo et al., 1994). The instrument is divided in two parts: identification data was gathered in the first part, and the second part consisted of a survey where the attitude toward people with disabilities is evaluated. It comprises 37 statements with 6 possible Likert answers. These are grouped in five different factors that shall act as dependent variables.

In order to carry out the following analysis, the items that show a negative valuation were codified in reverse for the values assigned to the scale. In this way, the highest score means a positive attitude toward people with disabilities.

The independent variables extracted from such instrument are: age, gender, training, specialization training and retraining courses in the area of Special Education, center where the teachers work, center characteristic, contact with people with disabilities, purpose and frequency of said contact.

The dependent variables are grouped in five different dimensions (Verdugo et al., 1992):

-Assessment of abilities and limitations: idea that the teacher has of people with disabilities regarding their ability to learn and perform; shows the inferences regarding skills related to task execution.

-Acknowledgement/denial of rights: acknowledgement of the individual’s fundamental rights, equality of opportunities, right to vote, to obtain credit and social integration.

-Personal implication; judgements related to potential behaviors that the person could have toward people with disabilities in personal, work and social situations.

-Generic rating: general statements and generic ratings the person has toward allegedly defining features of a person with a disability’s personality or behavior.

- Assumption: assumptions the teacher has about the idea people with disabilities have of themselves.

Procedure and data analysis

Previous to the investigation, pilot groundwork was carried out in a private school in the inner parts of the country to observe the teachers’ behavior toward the requested information. Once the teachers’ reaction toward the instrument was known, informed consent was requested from each participant and the scale to be filled out was handed in in an envelope and then returned to the corresponding researcher. APA’s ethical rules have been abided with.

Descriptive and comparative statistical analysis were carried out using the SPSS statistical package.

Results

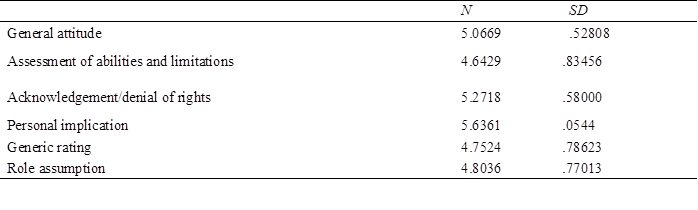

The average scores indicate that the teachers have a positive attitude toward people with disabilities (M = 5.0669). In Table 1, it can be seen that the subscale with the highest rating was Personal implication (M = 5.6361), followed by Acknowledgement/denial of rights (M = 5.2718). Role assumption (M = 4.8036), Generic rating (M = 4.7524) and Assessment of abilities and limitations (M = 4.6429) are below the overall average.

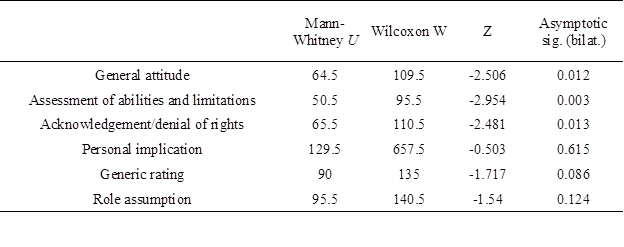

To compare the values, nonparametric tests were used, given that the data does not have normal distribution. Mann-Whitney’s U test is used to compare the average between the five dependent variables with the independent variables. Significant differences were found only regarding the variable (Table 2)

When the average is taken into account, it can be seen that the highest rating corresponds to teachers in general education in all three cases, as seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Variable average that show significant differences regarding the teacher’s initial training

No significant difference were found for the variables age (under 40/40 or older), years in the field (under 20 years in the field/20 years in the field or more), center’s characteristics (multiple grades per teacher/one teacher per grade), if they have worked in special education, have taken retaining courses, have contact with people with disabilities and have children with disabilities in their class.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the average related to the type of disability, the purpose and frequency of the contact but no significant differences were found for any of the five variables or for general attitude.

Having observed one of the items, it can be seen that the questions with the highest rating are no. 12 (People with disabilities should be able to have fun with everyone else) (t = 5.90), no. 10 (People with disabilities should be segregated in society) (with the same average) and no. 4 (Would you let your child accept an invitation to a birthday party of a child with a disability) (t = 5.88). These questions are the ones with the highest average.

The questions with the lowest average are no. 7 (People with disabilities operate like children in many aspects) (t = 3.62), no. 2 (A simple and repetitive task is the most appropriate task for people with disabilities) (t = 3.69) and no. 34 (The majority of people with a disability would rather work with other people who have the same disability) (t = 3.88). These questions correspond to the variables Assessment of abilities and limitations and Generic rating.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study’s main purpose was to understand the attitude teachers who work at state schools in our country have regarding their students with disabilities. According to the obtained results, it can be concluded that the attitude is positive, which matches with the consulted papers (Angenscheidt & Navarrete, 2017; Araya et al., 2014; Martínez & Bilbao, 2011; Moreno et al., 2006).

If the variables with the highest ratings are observed, it can be seen that, as many authors have stated (Araya et al., 2014; Martínez & Bilbao, 2011; Rodríguez, 2015), there is a positive attitude toward people with disabilities in the cases where teachers have or had interactions with people with disabilities in a personal, work related and/or social situation (Personal implication). The same occurs with regard to the acknowledgment of basic rights outside of the educational context, such as equality of opportunities, voting, obtaining credits, marriage, having children. However, the favorable attitude is limited by global statements regarding allegedly defining features of a person with a disability’s personality or behavior (Genetic qualification). The same occurs with the idea the teacher has regarding people with disabilities’ ability to learn and perform (Acknowledgement of abilities and limitations). Moreover, the obtained rating lowers due to what the teachers believe a person with disabilities’ idea of themselves is.

The first specific objective was to describe the personal factors that may determine a teacher’s attitude toward people with disabilities. No correlation has been found between attitude, age and years in the field, matching with what has been studied by Martínez and Bilbao (2011). The attitude is also not affected by whether the teacher has worked in special education or has taken retraining courses. Contact with people with disabilities does not seem to affect the attitude of the studied group, matching with what has been studied by Araya et al. (2014) and Macías (2016). Moreover, the results do not indicate a more positive attitude when the students were included, as also stated by Martínez and Bilbao (2011), who studied the attitudes of university professors in the city of Burgos.

However, the sample studied shows a favorable and statistically significant predisposition of the teachers in Common Education related to the teachers who, apart from having Common Education training, have also trained in Initial Education. The difference lies in their general attitude toward students with disabilities and the acknowledgement of their rights and their ability to learn and perform. These results match with Castaño (2012)’s who also uses the General Scale for Attitudes toward People with Disabilities by Verdugo et al. (1994), applied to a sample of 1.021 Teaching students in Spain. The author concludes that the Undergraduate students for Initial Education seem to have a poor belief in the possibilities people with disabilities have.

Having compared the attitude of the teachers and the context in which they work at (second specific objective), it can be concluded that, just as García and Alonso (1985) and Martínez and Bilbao (2011) established, there is no correlation between the attitudes with the center’s characteristics (where there are multiple teachers per grade/one teacher per grade)

With regard to obtaining empirical information regarding the ideas that predispose their conduct (third specific objective), the study of the dependent variables indicates that the teachers do not have doubts regarding the personality defining features of their students with disabilities, the idea they have about themselves, nor do they question the connection they develop with them. According to the identified significant differences, this investigation shows fewer positive attitudes in teachers who have training in Initial Education with regard to the rights of student and their ability to learn.

In order to explain the link found in this investigation between the teachers’ training and their attitude toward students with disabilities, characteristics of different study plans have been analyzed.

The teachers in Initial Education who were part of the sample were trained between 1994 and 2005, in accordance with the curriculum design established by Teachers’ Training Plan 1992 (ANEP, 1993) and its reform in the year 2000 (ANEP, 2000). This plan gave teachers the option to choose between General or Initial Education in their third year. If the second option was chosen, the degree had specific courses: Learning Orientation, Evolutive Psychology, Social Work, Play Psychosociology, Pedagogy, Musical, Body, Plastic and Linguistic Expression, Psychomotor Education (part of the course was for the teachers to be able to detect disruptions in the children’s psychomotor development), Biohygene (part of the course was Neuropsychic alterations in the preschooler). Within the population studied, teachers graduated in Initial Education have a double major, so the contents of these courses are additional to the training in General Education.

An already cited study carried out by Novo et al. (2015) based on the Theory of Reasoned Action indicated that the intention to support inclusion is conditioned by the perceived control, that is to say, the evaluation the individual makes whether a certain procedure can be easily carried out. Based on the collected theoretical information, it is possible to affirm, following the cited authors, that the initial training in attention to diversity of the teachers in Initial and Primary Education may be conditioning the perception of how easy it is to carry out inclusive conducts within the framework of primary schools in our country. This variable would affect the general attitude and the idea the teacher has towards their students with disabilities regarding their ability to learn and perform and recognizing their rights. Moreover, the studied sample refers to a group of teachers trained in Initial Education who are currently working in third cycles of Primary Education.

Based on the statements by Urbina et al. (2011), the teachers working at the highest grade in primary school constitute the least inclusive group, given their belief that there is a higher difficulty controlling the class and carrying out the curriculum with students with disabilities at this level. Authors have studied the ideas teachers have regarding disruptive conducts within the last school cycle during which the process of inclusion is perceived as hard and stressful. The students’ behaviors that interrupt school activities distort the normal development of the tasks carried out in class and force the teacher to invest a great part of the time needed for teaching. Teachers in our country, according to the 2007 Teachers’ Census, mention this as a major issue. Based on this, the cited authors promote the creation of spaces and opportunities for the teachers to delimit the contents ‘to stop and think’ about, regarding class disruption within the framework of the principles of inclusive education.

An adequate intervention proposal would be based mainly in creating spaces that provide listening options as a base for the implementation of educational policies that truly organize the support to tend to diversity, just as Booth and Ainscow (2002) state, to allow teachers to describe the activities that contribute to the center’s ability to respond to its students’ diversity. Thus, practices would be closer to the theoretical aspects of initial training since, taking into account Novo et al. (2015)’s conclusions, the attempt to support inclusion depends on whether the teacher believes it to be possible and to what degree it is possible to intervene.

Although the studied topic is not innovative, given that there have been numerous technics and instruments for the assessment of attitudes in different populations, this study may be beginning of an unexplored path of investigation on the attitudes of teachers who are working in State Schools in Uruguay. Given the limitations that are present in this study for its limited sample, it would be pertinent to extend the number, the variety, the representativity and the context, as well as emphasize the perceived control. It would also be necessary to investigate if the barriers Uruguayan state school teachers’ identify for an inclusive education can be modified based on the results of this study.

REFERENCES

Ainscow, M. (2012). Haciendo que las escuelas sean más inclusivas: lecciones a partir del análisis de la investigación internacional. Revista Educación Inclusiva, 5, 39-49. [ Links ]

Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP). (1993). Plan de Formación de Maestros 1992. Recuperado de https://www.anep.edu.uy/codicen/dsgh/formacion/programas [ Links ]

Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP). (2000). Propuesta de modificación Plan/92. Disponible en https://www.anep.edu.uy/codicen/dsgh/formacion/programas [ Links ]

Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP). (2007). Censo Nacional Docente. Recuperado de https://censodocente2018.anep.edu.uy/censo/contenido/2008dic-%20censo%20nacional%20docente%20-%20anep%202007.pdf [ Links ]

Angenscheidt, L. & Navarrete, I. (2017). Actitudes de los docentes acerca de la educación inclusiva. Ciencias Psicológicas, 11(2), 233-243. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v11i2.1500 [ Links ]

Araya, A., González, M. & Cerpa, C. (2014). Actitud de universitarios hacia las personas con discapacidad. Educación y Educadores, 17(2), 289-305. https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2014.17.2.5 [ Links ]

Baña, M., Fernández, M. & Fernández, L. (2006). Actitudes del profesorado hacia los alumnos con discapacidad. Memorias de las III Jornadas Innovación docente de la Universidad de La Coruña, España [ Links ]

Barton, L. (2011). La investigación en la educación inclusiva y la difusión de la investigación sobre discapacidad. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 70(25,1), 63-76. [ Links ]

Bolívar, A. (2010). La lógica del compromiso del profesorado y la responsabilidad del centro escolar. Una revisión actual. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 8, 10-33. [ Links ]

Booth, T. & Ainscow, M. (2002). Guía para la evaluación y mejora de la educación inclusiva: desarrollando el aprendizaje y la participación en los centros escolares. Madrid: OEI, FUHEM. [ Links ]

Castaño, R. (2012). Actitudes de los estudiantes de educación hacia la discapacidad. Un análisis diferencial de variables. En P. Miralles & A. Mirete (Eds.), La formación del profesorado en Educación Infantil y Educación Primaria (pp. 213-220). Murcia: Publicaciones Universidad de Murcia [ Links ]

Catalán, J. & González, M. (2009). Actitud hacia la evaluación del desempeño docente y su relación con la autoevaluación del propio desempeño, en profesores básicos de Copiapó, La Serena y Coquimbo. Psykhe, 18, 97-112. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-22282009000200007 [ Links ]

Centro de Archivos y Acceso a la Información Pública (CAinfo). (2013). Discapacidad y educación inclusiva en Uruguay. Recuperado de http://www.cainfo.org.uy/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/327_Informe-Educacion-Inclusiva-Difusion2013.pdf [ Links ]

Clasificación Internacional de Deficiencias, Discapacidades y Minusvalías (CIDDM). (1983). Manual de clasificación de las consecuencias de la enfermedad. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Servicios Sociales. [ Links ]

Consejo de Educación Inicial y Primaria (CEIP). (2011). Acta n.° 11. Resolución n. ° 9. Recuperado de http://www.ceip.edu.uy/documentos/carpetaarchivos/normativa/circulares/2011/actas/Acta11_Res9_11.pdf [ Links ]

Consejo de Educación Inicial y Primaria (CEIP). (2014). Protocolo de inclusión educativa de educación especial. Circular n. º 58. Recuperado de http://cep.edu.uy/documentos/2014/normativa/circulares/Circular58_14.pdf [ Links ]

Consejo de Educación Inicial y Primaria (CEIP). (2017). Monitor educativo. Uruguay. Recuperado de https://www.anep.edu.uy/monitor/servlet/consultaindicadores [ Links ]

Consejo de Formación en Educación (CFE). (2016). Expediente n. ° 2016-25-5-000470 - Seminario en educación de derechos humanos. Recuperado de http://www.cfe.edu.uy/images/stories/pdfs/planes_programas/seminarios/derechos_humanos.pdf [ Links ]

Consejo de Formación en Educación (CFE). (2017). Expediente n. ° 2017-25-5-007670. Seminario de Aprendizaje e Inclusión. Recuperado de http://www.cfe.edu.uy/images/stories/pdfs/planes_programas/seminarios/inclusion_diversidad.pdf [ Links ]

Colamarco, V. & Delamonica, E. (2013). Políticas para la inclusión de la infancia con discapacidad. Desafíos, Boletín de Infancia y Adolescencia, 15, 4-9. [ Links ]

Domínguez, J. & López, A. (2010). Funcionamiento de la atención a la diversidad en la enseñanza primaria según la percepción de los orientadores. Revista de Investigación en Educación, 7, 50-60. [ Links ]

Echeita, G. (2013). Inclusión y Exclusión Educativa. De Nuevo, “Voz y Quebranto”. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 11(2), 99-118. [ Links ]

Echeita, G. & Ainscow, M. (2011). La educación inclusiva como derecho: marco de referencia y pautas de acción para el desarrollo de una revolución pendiente. Tejuelo, 12, 26-46. ISSN: 1988-8430 [ Links ]

Echeita, G., Verdugo, M. A., Sandoval, M., Simón, C., López, M., González-Gil, F. & Calvo, M. (2008). La opinión de FEAPS sobre el proceso de inclusión educativa. Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 39(4), 228, 26-50. [ Links ]

Elices, J., Del Caño, M. & Verdugo, M. (2002). Interacción entre iguales y aprendizaje. Una perspectiva de investigación. Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada, 55, 421-438. [ Links ]

García, J. & Alonso, J. (1985). Actitudes de los maestros hacia la integración escolar de niños con necesidades especiales. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 30, 51-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.1985.10822070 [ Links ]

Gargallo B., Pérez C., Fernández A. & Jiménez M. (2007). La evaluación de las actitudes ante el aprendizaje de los estudiantes universitarios. El cuestionario CEVAPU. Revista Electrónica Teoría de la Educación. Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, vol. extraordinario, 238-258. [ Links ]

González, J. & Baños, L. (2012). Estudio sobre el cambio de actitudes hacia la discapacidad en clases de actividad física. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 12(2), 101-108. https://doi.org/10.4321/s1578-84232012000200011 [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M. (2007). Contextos y barreras para la inclusión educativa. Horizontes Pedagógicos, 9(1), 47-56. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2011). Censos 2011. Recuperado de http://www.ine.gub.uy/censos2011/index.html [ Links ]

León, O. & Montero, I. (2004). Métodos de investigación en psicología y educación. (3ª ed.). Madrid: Mc Graw-Hill. [ Links ]

Ley 18.418. (2008). Convención sobre los derechos de las personas con discapacidad. Poder Legislativo, Montevideo. República Oriental del Uruguay, 4 de diciembre de 2008. [ Links ]

Ley 18.651. (2010). Protección Integral a los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad. Poder Legislativo, Montevideo. República Oriental del Uruguay, 9 de marzo de 2010 [ Links ]

López, M., Echeita, G. & Martín, E. (2009). Concepciones sobre el proceso de inclusión educativa de alumnos con discapacidad intelectual en la educación secundaria obligatoria. Cultura y Educación, 21(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1174/113564009790002391 [ Links ]

Macías, E. (2016). Actitudes de estudiantes de magisterio en educación primaria hacia las personas con discapacidad. Revista Nacional e Internacional de Educación Inclusiva, 9(1), 54-69. [ Links ]

Martínez, M. & Bilbao, M. (2011). Los docentes de la universidad de Burgos y su actitud hacia las personas con discapacidad. Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 42, 50-78. [ Links ]

Martinis, P. & Redondo, P. (Comps.) (2006). Igualdad y educación. Escrituras entre (dos) orillas. Buenos Aires: Del Estante. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación y Cultura (MEC). (2017). Protocolo de actuación para la inclusión de personas con discapacidad en centros educativos. Disponible en https://www.mec.gub.uy/innovaportal/file/104231/1/protocolo-de-inclusion.pdf [ Links ]

Moreno, J., Rodríguez, I., Saldaña, D. & Aguilera, A. (2006). Actitudes ante la discapacidad en el alumnado universitario matriculado en materias afines. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 40(5), 1-12. [ Links ]

Novo, I., Muñoz, J. & Calvo, C. (2011). Análisis de las actitudes de los jóvenes universitarios hacia la discapacidad: un enfoque desde la teoría de la acción razonada. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 17(2), 1-26 [ Links ]

Novo, I., Muñoz, J. & Calvo, N. (2015). Los futuros docentes y su actitud hacia la inclusión de personas con discapacidad. Una perspectiva de género. Anales de Psicología, 31(1), 155-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.1.163631. [ Links ]

Organización de Naciones Unidas (ONU). (2006). Convención sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad y Protocolo Facultativo. Recuperado de http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-s.pdf [ Links ]

Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). (2011). Informe mundial sobre la discapacidad. Recuperado de https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/es/ [ Links ]

Ossa, C. (2008). Influencia de la cultura escolar en la percepción de docentes de escuelas municipalizadas acerca de la integración escolar. Horizontes Educacionales, 13(2), 25-39. ISSN: 0717-2141 [ Links ]

Ovejero, A. (2007). Las relaciones humanas. Psicología social teórica y aplicada. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

Perrenoud, P. (2004). Diez nuevas competencias para enseñar. Biblioteca para la actualización del maestro. México: Grao. [ Links ]

Priante, C. (2003). Mejoras en organizaciones de México y España mediante el desarrollo de una estrategia inclusiva. (Tesis doctoral). Recuperado de http://sid.usal.es/idocs/F8/FDO17184/tesis_priante.pdf [ Links ]

Reyes, L. (2007). La Teoría de Acción Razonada: implicaciones para el estudio de las actitudes. Investigación Educativa Duranguense, 7, 66-77. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, A., Álvarez, E. & García, R. (2014). La atención a la diversidad en la universidad: el valor de las actitudes. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 25(1), 44-61. https://doi.org/10.5944/reop.vol.25.num.1.2014.12012 [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M. (2015). Actitudes hacia la discapacidad en alumnos de Magisterio de Educación Infantil. Propuestas de formación para una Educación Inclusiva. Revista Nacional e Internacional de Educación Inclusiva, 8(3), 137-152. [ Links ]

Romero, F. J. (2006). ¿Hasta dónde debe llegar el compromiso como docente? Graffylia, 6, 39-45. [ Links ]

Sánchez, M. J., Borzi, S. & Talou, C. (2012). La inclusión escolar en la infancia temprana: de la Convención de los Derechos del Niño a la sala de clase. Infancias Imágenes, 11(1), 41-48. https://doi.org/10.14483/16579089.4551 [ Links ]

Seoane, J. (2011). Qué es una persona con discapacidad. Ágora, 30(1), 143-161. [ Links ]

Seva, S. (2016). Actitudes hacia la discapacidad en alumnos de Magisterio Infantil: la formación inicial docente. En J. L. Castejón (coord.), Psicología y educación: presente y futuro. Alicante: ACIPE, pp. 2.475-2.482. [ Links ]

Sierra, R. (1999). Técnicas de investigación social, teoría y ejercicios (13ª ed.). Madrid: Paraninfo. [ Links ]

Talou, C., Borzi, S., Vázquez, M., Gómez, M., Escobar, S. & Hernández, V. (2010). Inclusión escolar: reflexiones desde las concepciones y opiniones de los docentes. Revista de Psicología, 11, 125-145. ISSN: 0556-6274 [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2000). Marco de Acción de Dakar. Reuperado de http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001211/121147s.pdf [ Links ]

Urbina, C., Simón, C. & Echeita, G. (2011). Concepciones de los profesores acerca de las conductas disruptivas: análisis a partir de un marco inclusivo. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 34, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1174/021037011795377584 [ Links ]

Urmeneta, X. (2010). Discapacidad y derechos humanos. Norte de Salud Mental, 8(38), 65-74. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, B. A., Guillén, M. & Campa, R. (2014). Recursos para la inclusión educativa en el contexto de educación primaria. Infancias Imágenes, 13(2), 64-75. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.infimg.2014.2.a06 [ Links ]

Verdugo, M. A. (ed.) (2002). Personas con discapacidad: perspectivas psicopedagógicas y rehabilitadoras. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Verdugo, M. A. (2009). El cambio educativo desde una perspectiva de calidad de vida. Revista de Educación, 349, 23-43 [ Links ]

Verdugo, M. A. (2011). Implicaciones de la Convención de la ONU (2006) en la educación de los alumnos con discapacidad. Participación Educativa, 18, 25-34. [ Links ]

Verdugo, M. A. & Rodríguez, A. (2008). Valoración de la inclusión educativa desde diferentes perspectivas. Siglo Cero, 228, 5-25. [ Links ]

Verdugo, M. A., Arias, B. & Jenaro, C. (1994). Actitudes hacia las personas con discapacidad. Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Sociales. Instituto Nacional de Servicios Sociales. [ Links ]

Viera, A. & Zeballos, Y. (2014) Inclusión educativa en Uruguay: una revisión posible. Psicología, Conocimiento y Sociedad, 4(2), 237-260. doi: 10.1590/2175-3539/2018/055 [ Links ]

Wehmeyer, M. (2009). Autodeterminación y la tercera generación de prácticas de inclusión. Revista de Educación, 349, 45-67. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-0034-8082-RE [ Links ]

Zeballos, Y. (2015). Concepciones de infancia con discapacidad e inclusión educativa en estudiantes de magisterio de Lavalleja. (Tesis de Maestría). Disponible en https://www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12008/5494/1/Zeballos%2C%20Yliana.pdf [ Links ]

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M.M.B. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; I.N.A. in a,c,d,e

Correspondence: María Martha Bermúdez, e-mail: mmbermudez123@gmail.com; Ignacio Navarrete Antola, e-mail:inavarre@ucu.edu.uy

How to cite this article: Bermúdez, M.M., & Navarrete Antola, I. (2020). Teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(1), e-2107. doi: https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2107

Received: July 07, 2018; Accepted: April 20, 2019

texto en

texto en