Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.13 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2019 Epub 01-Dic-2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i2.1895

Short Communications

The concept of device-group on adoption support: denaturalizing established meanings

1Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Fedral de Santa Catarina. Brasil

2CAPES juliana.gomesfiorott@gmail.com

3Centro Universitário FADERGS Porto Alegre. Brasil

4Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Brasil

Keywords: adoption; adoption support; group; device-group; intervention-research

Palavras-chave: Adoção; apoio à adoção; grupo; grupo-dispositivo; pesquisa-intervenção

Palabras clave: adopción; apoyo a la adopción; grupo; grupo-dispositivo; investigación-intervención

Introduction

This article analyzes intervention-research done with members of an Adoption Support Group in the city of Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. To this end, use the concept of group of devices in the understanding of the results of the creation of working conditions, highlighting the work groups that are produced among the members of the group. Through the concept, the group experience ceases to be complete with a group of people gathered in the same place, with a single objective, to be interpreted as a whole for a production of meanings, which each builds upon the others, as well as , a problematization of historically instituted issues involving a group subjectivity (Barros, 2007).

The practices of the Adoption Support Groups involve, from the reception of people interested in joining the application for adoption, to parents who are already in their custody foster children. Groups also act as devices in the re-signification of conflicts and emotions that emerge in the period of waiting and after the arrival of the children. In this way, they stimulate psychic, affective, social and political processes, producing new subjectivities (Hur & Viana, 2016). At the same time, they enable experiences with peers who share similarities, which results in an identification of roles and also the demystification of preconceived contents (Sequeira & Stella, 2014).

In the expectation of the arrival of the child, the participation in groups can also support the maintenance of the adoptive project and raise questions about the modification of the idealized profile of the desired child, making it closer to the real profile of a foster child (Levy, Diuana & Pinho, 2009). In cases of modification of the desired initial profile, there is a reflection on the applicants 'adoptive project, including their self-analysis on the ability to develop affective bonds with a larger child, dealing with prejudice linked to the belief that older children will be' more problematic ', to reflect on the life trajectory already covered by the child/adolescent and the relation with possible future problems (Mello, Luz & Esteves, 2016).

Among the elements that involve adoption, understanding the group as a device to work with the subjectivities involved can facilitate the process of sensitization of the profile of the predentents to adoption and becomes relevant to increase the knowledge about other possibilities of adoption. Such a contribution of the concept of a device-group helps in the process of late adoptions, which are still considered difficult, increasing the chances of children and adolescents being welcomed and developing in a protective family environment.

With regard to the concept of device-group, it is broad and speaks of a complex and multilevel set in which Deleuze (1988), from a reading of Foucault, presents the device as a first ball, composed of lines of visibility and enunciation. In this perspective, Barros (2007) reflects that the device-group is connected in processualities and not in units, as well as it is decentered from its place of object of knowledge, being thus taken by a tangle of lines that in the group are crossed by the histories that compose in him.

Thus, this article analyzes how the concept of device-group makes it possible to denaturalize meanings instituted in the adoption process, producing other subjectivities involved. Adoption is still very much related to the idea of the biological model, in which the suitors define specific profiles, by normative logics, and in this, infants, children and adolescents, who do not fit these norms, go for a long time waiting for an adoptive family. Thus, understanding how an adoption support group can serve as a device for sensitizing and redefining the senses of adopting becomes central to the practices of psychology in this field.

Method

Investigation Type

The article deals with the report of a research-intervention of a qualitative nature, of participatory methodology, in which researcher and researched are coauthors of the process of intervention and social transformation (Aguiar & Rocha, 2007). From this, it was sought to understand how the concept of device-group allows the construction of new meanings about adopting it, producing subjective resignifications in the participants.

Participants

Eighteen members of the Adoption Support Group - "ELO, talking about adoption", linked to the National Association of Adoption Support Groups (AGAAD). The participants of the group were in different stages of the adoptive project: 1) in the stage of procedural habilitation; 2) waiting to be called to finalize the process and receive custody of the child; 2) in a period of adaptation with the child / adolescent.

Procedures for the Data Collection

In order to collect the data, the researchers were inserted in an adoption group, becoming facilitators and coordinators of the group. The group meetings lasted three months, with one meeting per month, lasting one hour and thirty minutes and an average of twenty participants per meeting. The systematics of the group proceeded through discussions that had as a question the following question: how do you understand late adoption and its relationship with society? The dialogues were recorded in voice and there were records in field diary.

Procedures for Data Analysis

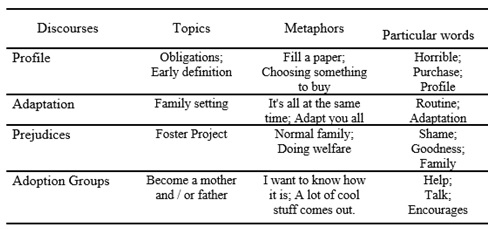

The data were transcribed, divided by themes and submitted to Discourse Analysis, under the Foucaultian perspective (Foucault, 2002), by continuous readings that established recurrent themes, specific metaphors and words with particular meanings, as Table 1. Articulated to the concept of device-group, Discourse Analysis integrates subjective questions to socio-historical aspects that are explicit in the different forms of discourse (oral language, writing, visual, institutions, politics, legislations, among other forms of human expression) (Fischer, 2012). Thus, the theoretical references of Schizoanalysis, such as Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and Brazilian authors such as Aguiar and Rocha (2007) and Hur e Viana (2016) were used to discuss the data. Such a framework allows us to consider the meanings about adoption as subjective processes of a particular socio-historical context, which explicitly establishes established statements and historically naturalized discourses.

Ethical Procedures

The accomplishment of the study that supports the construction of this article respected the guidelines and norms of Resolution 466 of December 12, 2012 of the National Health Council. After registration in the Brazil Platform, it was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) corresponding to the University Center, for evaluation and evaluation, which obtained approval, according to process nº 71001317.1.0000.5309. Participants were explained the objectives of the study, their risks and benefits, as well as the Free and Informed Consent Term (TCLE).

Results and Discussions

The research data were organized into four topics, according to the recurrence of the discourses in the group, as shown in Table 1.

These themes emerged in different forms of discourse, throughout the adoptive process and in the relationship with the device group, undergoing processes of resignification throughout the experiences. Next, the specifics of each one of them are presented, as opposed to the theoretical framework of the area.

Profile

The thematic profile was present in the participants' speeches based on different questions, one of them being the obligation to define it, as can be observed in the following statement: “when we started thinking about the profile, filling out that role that we even talked about here again in the group, that horrible role, it seems that we are choosing something to buy (P5)”. The requirement for this early definition of a profile, to be included in the National Justice Council suitors' register, with a need to specify detailed characteristics, often results in anxieties and fantasies about the process. (Reppold et al., 2005).

Beyond these anxieties and fantasies inherent in a device group, the logic of consumption appears in the discourse linked to adoption, when the group participant says: “It seems that you are choosing something to buy”. Adoption has historically been a mode of family constitution on the fringes of biological affiliation, and today there is a system that regulates and legally adopts. When there is the possibility of choosing the profile, in a consumption logic, there is an objectification of the child / adolescent, in which the human, affective and social factor is set aside, obeying a sterile and merely bureaucratic logic. It should be noted that the device group makes it possible to problematize the modes of constitution of institutions, their discourses (Barros, 2007) which, in this case, is present by the questioning of the norm imposed in the adoption process that is highlighted. Thus, from the doubts about the legal order around the profile, it becomes possible for the group to express the subjective effect that the instituted imposes through its crystallization.

In another moment of the speech, the utterance expressed refers to the definition of a profile understood as late adoption: “when we started talking about adoption, we already had a profile from 0 to 5 years old, because neither he nor I was seeing a baby. (P8)”. A study conducted specifically with adopters of older children looked at mothers 'and fathers' perceptions of the foster project and found that their motivation was related to pure altruism and the desire to perform as a parent, as well as practicality and desire of company (Dias, Silva & Fonseca, 2008). The device group, which tensiones fixed territories (Barros, 2007), is the example of the above clipping, in which the participants bring a report, which breaks with the normalizing logic of desire for the baby son, and are heard by others, thus allowing think of them in different possibilities.

Participants who have had the experience of direct contact with foster children demonstrate a broader conception of the desired profile for adoption. (Giacomozzi, Nicoletti & Godinho, 2015). This leads us to reflect on the possibility of interventions that bring adopters closer to the reality of children and adolescents in a situation of institutional care and already detached from their families of origin. The following speech is an example: “our first profile was from 0 to 3 and after we had contact with the kids from the shelter we stopped to think why not extend our profile to a bigger child so we went to the forum and put it up to eight years old (P4).” Such contact, when well conducted, can provide an approximation of the desired profile to the actual profile of the child received, demystifying stereotypes, breaking with the predominant model of affiliation.

Adaptation

The adaptation is a phase foreseen in the legislation, in which the professionals of the sticks of childhood and youth are monitored and begins after the first meeting between the postulants and adopters. In general, this stage begins with visits by the applicants to the host institutions, then with small departures, advancing to weekends at the home of the prospective parents and, finally, the temporary custody, in which the child or adolescent will live. along with your new family (Nabinger, 2010).

The adaptation period has subjective impacts as it causes changes in the routine, both for the family receiving the child and for the child or adolescent, who needs to become familiar with new environments, rules, etc. In couples situations, changes also occur in this relationship, which may seem to lose some of its intimacy and closeness due to the insertion of a new subject in the setting (Costa & Rossetti-Ferreira, 2007). In this context, adaptation is a necessary phase in which, gradually, the necessary modifications and adjustments occur for the occurrence of a new family configuration, as can be seen in these clippings: Adaptation is really necessary, because it's all at the same time, I've never been a mother, it's the first time, so it's the routine that changes, you have to adapt it all (P3) ”(...)“ There were times when I had no time to go to the bathroom. (P4).”

Prejudices

Another theme that emerges in the group's dialogues is related to prejudice against the adoptive project. Having a child by adoption is different from having a biological child, because adoption involves different legal, social and affective aspects of biological affiliation (Reppold & Hutz, 2003), however, the fact that they are different does not imply the classification of one of them as superior to the other. Yet often, through a purely philanthropic, welfare view, adoption is subjectively conceived more as an act of kindness than as a mode of family constitution (Barros, 2014).

Throughout the intervention research, the device group was presented as an important strategy for the deconstruction of normative family models. Normativity that was reflected in the subjective expression of the subjects in the group field, configured as prejudices around the adoptive project: family constitution models, racist and stereotyped views on ethnicity and race, hierarchical classification of children based on age and biological mark were being denaturalized. and resignified in other ways. Through psychological intervention in the group collectivity, discourses such as “shame, “beautiful”, “kindness”, “family constitution”, “philanthropy” and “welfare” they gained other significant contours, other subjective interpretations. In this regard, it is important to pay attention to the device group as something that presents itself as a warm network that carries, in its production process, a continuous production, which enables the construction of other worlds, other meanings, other outputs, different problems (Barros, 2007).

Adoption Groups

Regarding the understanding of the role of groups with the adoption theme, it can be stated that they effectively transform subjectivities in the process of becoming a mother and / or father by adoption (Comin, Amato & Santos, 2006; Scorsolini-Comin & Santos, 2008; Levy, Diuana & Pinho, 2009). This happens from the first moment that the idea of adoption is still being built, as it can be seen in the speech: “the groups really help us, at this moment I want to know how it is, we start talking and a lot of cool things come out. (P17)”. At the same time, it is necessary to problematize that the group-device, beyond being a mechanism of clarification and doubts, is permeated by a tangle of lines, which are configured from the different stories that cross it (Barros, 2007).

Following the same logic, such groups, as devices, also act in the demystification of stereotypes and broadening the conception of adoption, as can be evidenced: “we start listening to our colleague there, who already has a big son, who is difficult, but that is working, you will encourage him (P18)”. In this logic, the relevance of the exchange and sharing of experiences, subjective expressions and expansion of possibilities is based on the discourse of the other, constituted through the encounter (Scorsolini-Comin & Santos, 2008). Thus, the device group is understood as an intervention device of psychology that is not exempt from an active engagement in the ethical and socially implied dimension by which it chooses to build.

Final Considerations

This article aimed to analyze the process of an intervention research, conducted with members of an adoption support group, in relation to the concept of group-device. From the data, it was found that the concept helps in understanding the pathways of creation of group conditions, emphasizing the singular movements and their historically established location that involves group subjectivity. In the adoption field it was possible, through the results, to show how device group can denaturalize instituted meanings related to: the desired adoption profile; the impasses of adaptation; the prejudices involved in adopting; and the group movements that emerge in this field of intervention of psychology.

Through the speeches produced in the group, it was possible to identify that the participation in the groups, besides the exchange of experiences, also allows a reflection about their own adoptive project. Thus, the device group can be a powerful space for deconstructing subjective meanings about normative family models, based on group utterances that break with this logic and report adoptive experiences with older children. These deconstructions can help transform the conception of adoption, expanding it to profiles of children and adolescents that would rarely be adopted without a denaturalization of established meanings about adoption.

Thus, it is concluded that adoption support groups are important practices, when conducted in order to allow a space for reflection, as they act as a device for the denaturalization of meanings established in the adoption process. The concept of group-device, in this context, becomes an important intervention device for the area of psychology because it enables the expansion of subjective conceptions historically instituted at the collective, social, individual and unconscious levels. By emphasizing the singular movements that emerge in the group field, the concept enhances the affirmation and production of localized subjectivities, allowing other meanings about care, protection and family constitution to be produced. By reframing these meanings, a psychology is affirmed that intervenes ethically so that the right of every baby, child or adolescent, to live in family receiving affection and material and subjective investments, is assured regardless of their age, gender, ethnicity or race.

REFERENCES

Aguiar, K. F. D., & Rocha, M. L. D. (2007). Micropolítica e o exercício da pesquisa-intervenção: referenciais e dispositivos em análise. Psicologia: ciência e profissão, 27(4), 648-663. [ Links ]

Barros, R. B. D. (2007). Grupo: a afirmação de um simulacro. Porto Alegre: Sulina. [ Links ]

Barros, R. M. S. (2014). Adoção e família: a preferência pela faixa etária, certezas e incertezas. Curitiba: Juruá Editora, 146 p. [ Links ]

Comin, F. S., Amato, L. M., & dos Santos, M. A. (2006). Grupo de apoio para casais pretendentes à adoção: a espera compartilhada do futuro. Revista da SPAGESP, 7(2), 40-50. [ Links ]

Costa, N. R. D., & Rossetti-Ferreira, M. C. (2007). Tornar-se pai e mãe em um processo de adoção tardia. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 20(3). [ Links ]

Dias, C. M. D. S. B., Silva, R. V. B. D., & Fonseca, C. M. S. M. D. (2008). A adoção de crianças maiores na perspectiva dos pais adotivos. Contextos Clínicos, 1(1), 28-35. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. (1988). Foucault. U. de Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Fischer, R. M. B. (2012). Trabalhar com Foucault: arqueologia de uma paixão. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 113-132. [ Links ]

Foucault , M. A Arqueologia do Saber, 7ª. Ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2002. [ Links ]

Giacomozzi, A. I., Nicoletti, M., & Godinho, E. M. (2015). As representações sociais e as motivações para a adoção de pretendentes brasileiros à adoção. Psychologica, 58(1), 41-64. [ Links ]

Levy, L., Diuana, S., & Pinho, P. G. R. (2009). O grupo de reflexão como estratégia de promoção de saúde com famílias adotivas. Mudanças-Psicologia da Saúde, 17(1), 39-42. [ Links ]

Mello, M. M., Luz, K. G., Esteves, C. S. (2016). Adoção Tardia: Contribuições do projeto DNA da Alma de Farroupilha/RS. Saúde e Desenvolvimento Humano, 4(1), 37-46. [ Links ]

Nabinger, S. (2010). Adoção: O encontro de duas histórias. Santo Ângelo: FURI. [ Links ]

Reppold, C. T., & Hutz, C. S. (2003). Reflexão social, controle percebido e motivações à adoção: características psicossociais das mães adotivas. Estudos de psicologia (Natal)8 (1) (jan./abr. 2003), p. 25-36. [ Links ]

Reppold, C. T., Chaves, V., Nabinger, S., & Hutz, C. S. (2005). Aspectos práticos e teóricos da avaliação psicossocial para habilitação à adoção. Violência e risco na infância e adolescência: pesquisa e intervenção, 43-70. [ Links ]

Sequeira, V. C., & Stella, C. (2014). Preparação para a adoção: grupo de apoio para candidatos. Psicologia: teoria e prática, 16(1), 69-78. [ Links ]

Scorsolini-Comin, F., & Santos, M. A. D. (2008). Aprender a viver é o viver mesmo: o aprendizado a partir do outro em um grupo de pais candidatos à adoção. Vínculo-Revista do NESME, 5(2). [ Links ]

Hur, D. U., & Viana, A. D. (2016). Práticas grupais na esquizoanálise: cartografia, oficina e esquizodrama. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 68(1). [ Links ]

Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. J.G.F has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; Y.A.P. in a,c,d,e; D.D.I.E. in c,d,e.

Juliana Gomes Fiorott. Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas (UFSC). R. Eng. Agronômico Andrei Cristian Ferreira, s/n - Trindade, Florianópolis - SC - Brasil; e-mail: juliana.gomesfiorott@gmail.com.

Fiorott, J. G., Palma, Y.A., & Ecker, D.D.I. (2019). The concept of device-group on adoption support: denaturalizing established meanings. Ciencias Psicológicas, 13(2), 390 - 397. doi: 10.22235/cp.v13i2.1895

Received: December 04, 2018; Accepted: July 17, 2019

texto en

texto en