Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.13 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2019 Epub 01-Dic-2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i2.1890

Original Articles

An analysis of normative perception, and its relation to values and psychosocial well-being

1 Universidad de Buenos Aires. Argentina, maiteberamendi@gmail.com

Key words: norms; transgression; values; well-being; workers

Palabras clave: bienestar; normas; trabajadores; trasgresión; valores

In recent years, an increase in normative transgression in Argentina may be seen. It appears as a common and deeply rooted practice since all kinds of transgressions are displayed on a daily basis ranging from failure to follow rules of coexistence to acts of political corruption (Beramendi 2014; Beramendi & Zubieta, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018). This has allowed to speak of a culture of Argentina transgression that gives account of practices and beliefs that perpetuate the regulatory breach (Beramendi, 2014; Nino, 2005). Beginning with high rates of transgression and the factors that influence the perception of lack of institutional legitimacy, the need to investigate the relationship of individuals with norms and their institutions arises, not only at the individual level but from an approach that contemplates a more complex psychosocial perspective (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014, 2018). Within this complex framework that relates to the individual and society, individual and collective values are configured that materialize in norms, and function as frames of reference in the organization and control of social and institutional dynamics (Gouveia, Milfont, Fisher & Santos, 2008; Gouveia, Milfont & Guerra, 2014). These values, by guiding behavior and functioning as cognitive representations of both human needs and institutional and societal demands (Gouveia et al., 2008; Gouveia, Milfont, Fisher & Coelho, 2009), influence the perception of the normative system - and the consequent action -, and these both, due to their personal impact, influence well-being (Schwartz, 2012).

Normative Transgression

Within the framework of social psychology, Beramendi (2014) and Beramendi & Zubieta (2014, 2018) propose a model to analyze the functioning of the normative system, defined as a complex organism that includes norms, institutions and agents that promote, support and control them, as well as citizens' normative beliefs and practices about norms. The normative system contemplates three dimensions:

1. The perception of legitimacy: it is an evaluation that is carried out on the perception of justice in the organization of institutions, the management of the authorities and the social distribution of resources. Lack of legitimacy would lead people not to voluntarily accept the rules, because they believe it is not "right" or "fair." This promotes the instability of any institutional structure. There would be six attributes that would contribute to this lack of legitimacy: negative perception of economic distribution, negative perception of the functioning of justice processes, low institutional confidence, perception of corruption, perception of institutional inefficiency, and the degree of authoritarianism on the part of the authorities.

2. The perception of transgression: it is an evaluation of the perception of beliefs and standards of transgressive behaviors in a society, which are not congruent with the socially expected. To this end, five attributes are envisaged that would enable a greater perception of social transgression: the degree of lack of sanction and normative control, associated with the belief that in the absence of control or sanction by the competent authorities people will tend to violate the norms, habituation, generalization and naturalization about normative non-compliance, and, finally, if people develop individual normative systems according to their own values, customs and/or individual norms.

3. The perception of normative weakness: it is a negative assessment that is made on the power of the norm, determined by the obedience and credibility of the standards that should be fulfilled. It is made from three attributes; the arbitrariness, organization and management of institutions based on double standards where informal norms have more power than formal ones and the power of authority over the power of the norm.

Various investigations were carried out based on this approach, which analyzed the perception of the normative system and different variables. A cross-cultural study was carried out comparing Argentine, Peruvian and Venezuelan citizens, resulting in the perception of the normative system being more negative in Venezuela, followed by Peru and finally Argentina (Beramendi, Espinosa & Acosta, 2019). In the local context, research shows that in Argentina emerges mainly the lack of institutional legitimacy, which is directly related to transgression - a naturalized and accepted fact - and the perception of a double standard of formal and informal norms that coexist. And women were found to have a greater negative perception than men of the normative system (Beramendi, 2014). Likewise, in Buenos Aires, university students and future officers of the Argentine army perceived that the functioning of the normative system is adverse, and is associated with feelings of social demoralization, and negative emotions/feelings such as sadness and mistrust (Beramendi & Zubieta, 2016).

Values

One of the most recognized theories of values at present is the theory Functional Theory of Human Values (Gouveia et al. 2008). This presents an integrative model that includes four main assumptions: 1) Human Nature: it takes on the benevolent or positive nature of human beings, so that it only admits positive values. 2) Motivational Basis: values are assumed as cognitive representations of human needs but also of institutional and societal demands. 3) Terminal Character: only terminal values have been taken into account, conceived as superior and transcendent cognitive goals, not being restricted to immediate and biologically urgent goals. 4) Individual Guiding Principles: values incorporated by the culture that have been useful for the survival of the group, making them desirable, and that enable the continuity of society, enabling general categories of guidance for the behaviors of individuals.

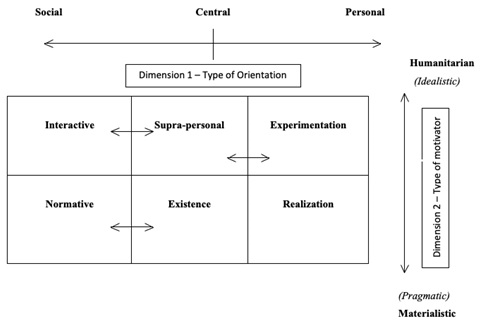

Gouveia, Santos, Athsyde, Souza and Gusmão (2014) have identified two main functions of human values: (1) guide actions (type of orientation) and (2) represent human needs (type of motivator). The first function presents three orientation possibilities: social, central and personal. The second function of values is to cognitively represent human needs. In this sense, all values can be classified as materialistic (pragmatic) or humanitarian (idealistic). Materialistic values are related to practical ideas, and an orientation towards specific goals and regulatory rules. Humanitarian values express a universal orientation, based on more abstract ideas and principles. In this way the horizontal axis would correspond to the function of values to guide human actions, while the vertical axis would indicate the function of the values to cognitively represent human needs.

According to Figure 1, the three types of orientation are represented by two sub-functions each: social (normative and interactive), central (existence and supra-personal) and personal (realization and experimentation). Similarly, three sub-functions represent each of the motivating types: materialism (existence, normative and realization) and humanitarian (supra-personal, interactive and experimentation). Therefore, it is possible to speak of six differentiated quadrants: social-materialist, central-materialist, personal-materialist, social-humanitarian, central-humanitarian and personal-humanitarian (Gouveia, Milfont et al., 2014).

Both functions and sub-functions of the values are latent structures, which require a representation through specific indicators or values. Gouveia, Milfont et al. (2014) describe six sub-functions:

a. Existence sub-function. It represents the materialistic motivator and represents a central orientation. Health, survival and personal stability are values that can represent this sub-function.

b. Realization sub-function. Values based on a personal principle to guide the lives of individuals, while emphasizing material realizations (e.g., success, prestige and power).

c. Normative sub-function. Materialistic motivator with a social orientation, reflecting the need for control, preserving culture and conventional norms (e.g., tradition, obedience and religiosity).

d. Supra-personal sub-function. They represent the aesthetic, cognition, and self-realization needs (e.g., knowledge, maturity and beauty). Defined as humanitarian, oriented by a central type.

e. Experiment sub-function. The physiological need for satisfaction or the inclination towards the pleasure principle (hedonism) (e.g., sexuality, pleasure and emotion). Humanitarian motivator, but with a personal orientation.

f. Interactive sub-function. Humanitarian motivator, but with a social orientation. Common destiny, affective experience between individuals, and needs for belonging (e.g., affectivity, coexistence and social support).

Welfare

The psychological and social perspective of health and well-being envisions an approach that accounts for the interrelationship of individual and social needs as promoters of well-being or discomfort. It is a question of studying not only the psychological criteria but also the social criteria of well-being, that is, the relationship of people with their environment and how it ensures their well-being of relational and microsocial criteria, which society must offer the person for it to meet its needs (Hervás & Vázquez, 2013).

The need for brief and comprehensive measures that can be used to perform rapid, reliable and valid assessments of well-being promoted the development of the Integrative Welfare Model, The Pemberton Happiness Index (PHI) (Hervás & Vázquez 2013) validated for a variety of languages and countries since its inception. Hervás and Vázquez (2013) proposed a comprehensive approach which incorporates three types of well-being: subjective, psychological and social.

Subjective well-being: defined as "a broad category of phenomena that includes people's emotional responses, satisfaction with domains and global judgments about life satisfaction" (Diener, Suh, Lucas & Smith, 1999, p .277). It is linked to the hedonic tradition of well-being, which attributes that well-being consists of subjective happiness, and refers to the experience of pleasure versus displeasure.

Psychological well-being: Ryff and Keyes (1995) focused their attention on capacity development and personal growth, conceived as key indicators of positive functioning, both personal and interpersonal perception, appreciation of the past, participation in the present and mobilization for the future (Valle, Beramendi & Delfino, 2011). Linked to the eudaemonic tradition of well-being, which indicates that true happiness is found in the expression of virtue; in doing what is worth doing (Ryan & Deci, 2001), as well as in living a life that represents human excellence (Ryan, Huta & Deci, 2006).

Social welfare aims to characterize positive functioning, not at the private and personal level, but at the level of the individual's relationship with the public and social domain (Keyes, 1998). That is, to give relevance to “the individual as well as the social, to the given world as to the inter-subjectively constructed world, to nature and to history” (Blanco & Diaz, 2005, p. 585). Keyes (1998) points out that each person's evaluation of the circumstances (social welfare), and the functioning of society is also necessary to think and understand the concept of well-being.

Objectives

The overall objective of this research is to analyze the relationship between the perception of the normative system, psychosocial well-being, and human values in workers in the private and public sphere of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and Conurbano Bonaerense. Specific objectives are expected to describe the perception of the normative system, psychosocial well-being, and human values in private and public workers of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and Conurbano Bonaerense. And on the other hand, to investigate differential profiles in the psychosocial aspects mentioned in the main objective based on socio-demographic aspects, such as age, gender, place of residence, religious practice, work environment and psychosocial aspects such as economic self-perception economic and ideological self-positioning.

Method

Design and type of study

The study design is non-experimental, transversal, being a type of descriptive-correlational study.

Participants

The sample was non-probabilistic and intentional, and comprised of 148 workers resident in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (40.5%) and Conurbano Bonaerense (59.5%). 33.85% (n = 50) belong to the male gender, and 66.2% (n = 98) to the female gender, with an average age of 31.40 years (SD = 10.99; Min = 20, Max = 77). The organizations in which the participants work are 66.9% in CABA and 33.1% in Conurbano Bonaerense. They differ between public-sector institutions, 18.9% (n = 28), and private-sector, 81.1% (n = 120). 35.8% express working between a range of 10 and 5 years, followed by 31.1% who express work less than 5 years ago. The overall average working time in the current organization is 5.83 years (SD = 8.30).

Instruments

A self-administered questionnaire consisting of the following scales, and a set of psychosocial questions was designed:

Normative System Perception Scale (EPSN, Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014): composed of 20 items that are organized in three dimensions that assess the Perception of Lack of Legitimacy, the Perception of Transgression and the Perception of Normative Weakness. Items such as “public bodies are inefficient” or “many norms are arbitrary and meaningless” are presented, whose responses are presented in a Likert scale format, from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree) . High scores account for a negative perception of the normative system. The internal consistency of the scale that was applied in this study was acceptable (α = .86).

Basic Values Questionnaire (CVB, Gouveia et al., 2014): the most current version consists of 18 items/values. The questionnaire presents two descriptions for each value (for example, EMOTION: enjoy challenges or unknown situations; seek adventures / TRADITION: follow the social norms of your country; respect the traditions of your society). Each item is evaluated on a seven-point scale, with the following extremes: 1 (Totally unimportant) and 7 (Most important), considering its importance as a guiding principle in their lives. The internal consistency of the scale dimensions that were applied in this shot were acceptable: experimentation (α = .53), realization (α = .42), existence (α = .31), supra-personal (α = .45), interactive (α = .31) and normative (α = .54).

Pemberton Happiness Index (PHI, Hervás & Vázquez, 2013): designed to measure happiness in the general population, it consists of 11 items related to remembered well-being, each with a Likert scale of 11 points; where 0 strongly disagrees and 10 totally agree. The well-known scale of PHI is considered one-dimensional. The well-being score remembered is calculated with the average score of the 11 items and can vary from 0 to 10. The internal consistency of the scale that was applied in this shot was acceptable (α = .87).

Socio-demographic questions: age, gender, city of residence, location of the organization in which you work.

Procedure

Data collection was carried out based on two modalities: online version and paper version. The online version was made from the SurveyMonkey platform. For the paper version, the lead researcher approached private and public companies to apply the questionnaire. The administrations were individual.

Data collection was carried out from November 2016 to February 2017. All participants were given an informed consent that explicitly stated participation was voluntary, that the information was confidential and that it would only be used for academic purposes. Data analyzes were performed based on the SPSS 21 statistical program.

Results

Descriptive analysis of scales

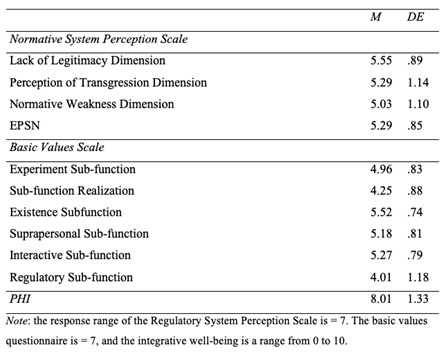

From the data obtained, as observed in Table 1, participants perceive the Argentine normative system negatively. The worst evaluated dimension was the Perception of Lack of Legitimacy, followed by the Perception of Transgression, and finally by the Perception of Normative Weakness dimension. To compare the scores between dimensions, a repeated measures ANOVA was calculated. The data indicates that the Mauchly sphericity test is rejected, so the Greenhouse-Geisser correction is used, which indicates that there is a difference between the dimensions, F (1, 915) = 17.303, p <.001. To observe the differences between these, the main effects were compared, corroborating the differences between all the variables of the scale and the order named.

In relation to the results of the Basic Values scale, Table 1 shows the descriptive analyzes that indicate the scores obtained by the participants. As in the previous analysis, a repeated measures ANOVA was carried out, which rejected the Mauchly sphericity test, indicating that there are differences between the sub-functions, F (4, 173) = 79,806, p <.001. In addition, to observe the differences between the sub-functions, the main effects were compared. This resulted in the existence sub-function obtaining the highest scores. Next, the interactive and supra-personal sub-function also reflected high scores. While the experimentation, realization and regulation sub-functions showed lower ratings, being the last one that obtained the lowest score.

With respect to the Integrative Wellbeing Scale (PHI), the sample score indicates that participants have high well-being. In this sense subjective, psychological and social well-being are integrated allowing optimal functioning of the person as well as interaction with the social context (Table 1).

Comparison between variables associated with work

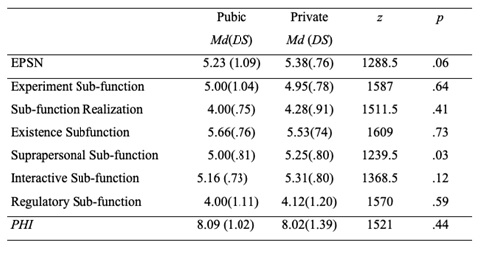

In relation to the variables associated with the work, we can observe in Table 2 that there is no difference in the perception of the normative system according to the scope of work of the participants. Regarding the comparison of values, it can be seen that the only difference is found in the Supra-personal sub-function where private sector participants have higher scores. No significant differences were found regarding the residence of the workplace.

On the other hand, differences were found in relation to the distinct groups representing different ranges of years of work, where people who have been working for 5 to 10 years have higher scores in the experimentation sub-function (z = 10,840, p = .03 ).

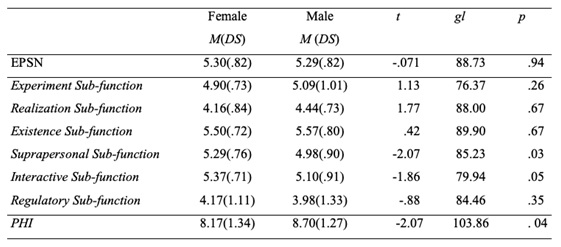

However, regarding the analysis of the socio-demographic variables evaluated, Table 3 shows that differences were found with respect to gender, particularly in the supra-personal and interactive sub-functions, these being mostly valued by women. Also relevant differences were found regarding the welfare of workers, where it is observed that women perceive less well-being in relation to men.

Regarding the differences according to the age of the participants, only differences in the values were observed. From the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Bonferroni contrast analysis, younger participants were found to have mostly experimental values than larger (z = 11.29, p = .01). In addition, differences were found between the older and middle-aged groups, with the first group presenting the highest scores (z = 7.18, p = .03). In relation to the normative dimension, it is observed that there are only differences between the middle-aged group and the smallest group, the first ones having the highest scores (z = 7.87, p = .02).

On the other hand, differences were found between workers residing in CABA and Conurbano Bonaerense, with the last ones having the lowest scores in the normative dimension, t(146) = 2,264, p = .03; MCABA = 4.37, SD = 1.24; MConurbano = 3.93, SD = 1.12). Regarding the educational level, this socio-demographic variable was regrouped, and a differentiation of the variable between primary, secondary, tertiary and university was obtained. The results show that no differences were found between the variables analyzed and the educational level of the workers.

Relationship between the variables

To analyze whether there was a relationship between the perception of the normative system, values and well-being, a Pearson correlation analysis was performed. No relationship was found between the perception of the normative system, values and well-being. Instead, a relationship was found between values and well-being. More precisely between the supra-personal sub-function and the PHI (r (148) = .18, p = .03), and the interactive sub-function and the PHI, r (148) = .18, p = .03.

Discussion

The results reveal that there is no relationship between the perception of the normative system, values and well-being. These data attracts attention as these concepts are understood as part of a system that interacts and influences each other, and as part of the social framework that converges in the creation of cultural and individual identity. Understanding by this fact that, whether positively or negatively, a relationship between variables would be found as part of the complexity that makes to society.

Previous studies (Gouveia et al., 2008, Gouveia, Milford et al., 2014; Schwartz, 1977) argue that values being holistically engaged to people affect their way of perceiving the norm, and this will affect well-being. But, it is likely that a context where transgression is part of the socialization process, historically and culturally rooted, directly influencing the legitimacy of institutions, will no longer have an impact on other complex processes of individuals because it is naturalized.

On the other hand, it is clear from the results a relationship between well-being and the values of the workers. The integration between deeply rooted values, which are holistically or totally engaged in the life of the individual, allows the optimal development of psychological and health capacities, as well as cognitive thinking (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). The results showed more precisely a relationship between well-being and values such as knowledge, maturity, beauty, affectivity, coexistence and social support. These values are mainly represented by young people (Gouveia, Santos et al., 2014), and are characterized as values that respond to a more idealistic or humanitarian motivation where it does not affect whether or not there is access to the necessary and basic material goods for the survival, which are more associated with the incidence of social norms to access them. This research was mainly formed by young people, which would explain the results.

The findings show that workers believe to a greater extent that there is a lack of legitimacy associated with the lack of distributive and procedural justice, corruption events, low efficiency and institutional trust, and authoritarianism by the authorities. In the second instance, participants perceive high levels of widespread transgression that are rooted in shared beliefs and patterns, as well as visualize low levels of control and sanction with respect to non-compliance with the rules. Transgression appears as a shared and naturalized belief in the Argentine context, which alerts and induces rethinking the concept of norm, since it has a negative aspect, associated with arbitrariness and meaninglessness. Finally, to a lesser extent, workers believe that norms are arbitrary and meaningless, and perceive double institutional standards, where informal norms have more power than formal ones, suggesting that transgression is introduced into the institutional life of Argentine society by imposing guidelines of interaction that live with her. As they also believe that the authorities of the institutions are above the norms. In this way, people visualize transgression not as an isolated and reduced fact to a specific group of society, but as something that is embodied in a generalized and rooted way in the social framework. These results are consistent with previous research conducted in the local context (Beramendi, 2014; Beramendi et al., 2019; Beramendi & Zubieta, 2014, 2018).

Regarding psychosocial repercussions, workers manifest a type of central orientation of values, and the type of motivator has a tendency to be mostly humanitarian (Gouveia et al., 2014), which does not mean that participants are better represented by materialistic values, or one cannot speak of a tendency towards the social or personal. That said, it was observed that health, survival and personal stability are the most esteemed values, representing a central orientation with a materialistic motivator. Which are preferred by individuals in contexts of economic scarcity, or by those who have been socialized in such environments (Inglehart, 1977). However, participants also highlighted equal peer relationships, the universal principle of orientation, and the openness to change that represent a humanitarian motivation. Usually it is the young people, mostly in this research, who are characterized by this type of motivator, where equality of groups and change are some values that represent them. And justifying that, on the contrary, the importance of preserving conventional culture and norms, valuing the religiosity and tradition, are some of the aspects less valued by the participants. We find that older people are typically more likely to be guided by these values (Rokeach, 1973). Prioritizing normative values would show that obedience to authority is important.

On the other hand, in terms of psychosocial well-being, the results showed a high level of well-being in the workers. This suggests a high capacity of development and personal growth, both conceived as main indicators of the positive functioning of mental health (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Positive relationship of workers with their own satisfaction, emotions, and a feeling of happiness based on high subjective well-being (Rodríguez-Carvajal, Díaz, Moreno-Jiménez, Blanco & van Dierendock, 2010). It is striking that there is no direct impact of the transgressive system on welfare. That is to say, the results obtained are contradicted, since they refer to a high social well-being that implies the relationship of the individual with the public and social domain (Valle et al., 2011), and high scores were obtained in the negative assessment that the workers make of the circumstances and the normative functioning within society.

On the other hand, because there were no differences in the perception of the normative system among those who work in the public sphere of the private sector, it is possible to indicate a generality in the institutional normative problem that crosses the whole society and is not limited to an area of society in particular. Although there is no difference, private sector workers are those who claim to have greater well-being. In this sense, one might think that the private sphere is characterized by a more positive organizational climate and working conditions, where labor and personal development, stability, and satisfaction of life goals are promoted, allowing us to talk about a psychological functioning more positive.

Since transgression is an accepted and collectively applied social norm, normative non-compliance becomes a descriptive social norm (Cialdini, 2007), which informs people about how they should behave normatively, works only as adaptive and context-effective behavior (Beramendi, 2014). Therefore, workers adopt, on the one hand, a way of managing with respect to norms, dissociating their actions, legitimized by the rest of society, from their personal integration with society. In this sense, autonomy and social coherence is maintained. Well-being, in addition of being promoted by the work environment, could be thought as a result of a differentiation between acting in society, and the own and individual search for integrative well-being.

Regarding gender, women were found to attach greater importance than men to values of knowledge, maturity and beauty, which is associated with a current cultural context that gives value to aesthetics and self-improvement. And at the same time, they represent the needs of belonging, love and affiliation, values that are mostly expected, allowed and socialized in the female gender. In addition, they score highest in relation to well-being. The data is consistent with previous research where women measure better in relation to men, showing stability and trust needs more satisfied (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). From a social perspective, women better assess the quality of their relationships with society or their groups of belonging, while feeling more useful, as they manage to make the most of the environment and contribute to the common good (Zubieta, Muratori & Fernández, 2010).

In the age variable it was found that the youngest prioritize the satisfaction of basic physiological needs (e.g., eating, drinking, sleeping) and the need for security, directly associated with the socio-economic context. Moreover, in the society they build, values are no longer primarily linked to production. Work no longer carries with it the signs of social recognition (Sanchis, 1988) giving rise to another type of current social recognition such as the search for happiness and satisfaction. Likewise, it was observed that this group differs from those of middle age, who are more in agreement with the importance of preserving culture and conventional norms. It corresponds to previous research, where older people are typically more likely to be guided by these values (Gouveia et al., 2015). Consequently, it is the young people who have just begun their employment and who have been working for 5 to 10 years. They observe the need for satisfaction and pleasure, and the promotion of changes and innovations in the structure of social organizations, all characteristics commonly adopted by young people.

One of the possible limitations of the sample is the non-probabilistic nature and the mainly focus on a small part of Argentina (CABA and Conurbano). Another limitation that was found is the absence of counterbalance of the scales.

These findings are useful as a diagnostic tool to understand the beliefs and practices that support normative transgression in institutions and, depending on them, work on interventions aimed at promoting their change, such as understanding the values that sustain these practices and their impact on people's well-being. These limitations will be considered in future studies while incorporating new analysis variables as well as new measures to assess well-being. It is relevant to continue addressing the phenomenon of transgression in the local context, as the perception levels of normative malfunction are high and completely harm society as a whole.

REFERENCES

Beramendi, M. (2014). Percepción del sistema normativo, transgresión y sus correlatos psicosociales en Argentina (Tesis doctoral inédita). Facultad de Psicología. Universidad de Buenos Aires: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Beramendi, M., Acosta, Y., & Zubieta, E. (2016). Polarización sociopolítica y percepción del sistema normativo en Venezuela. Psychologia: Avances de la Disciplina, 10(1), 35-45. doi: 10.21500/19002386.2464. [ Links ]

Beramendi, M., Espinosa, A. & Acosta, Y.(2019). Percepción del Sistema Normativo y sus correlatos psicosociales en Argentina, Perú y Venezuela. Manuscrito enviado para su publicación. [ Links ]

Beramendi, M. & Zubieta, E. (2013). La identidad nacional y las relaciones sociales en una cultura de la transgresión. Revista de Psicología Política, 13(26), 165-177. [ Links ]

Beramendi, M. & Zubieta, E. M. (2014). Norma Perversa: transgresión como modelado de legitimidad. Universitas Psychologica, 12(2). doi:10.11144/javeriana.upsy12-2.nptm [ Links ]

Beramendi, M. & Zubieta, E. M. (2015). Un estudio exploratorio sobre la relación entre la legitimidad institucional y la transgresión normativa en Argentina. Ciencias Psicológicas, 9, 15 - 26. Montevideo. [ Links ]

Beramendi, M. & Zubieta, E. (2016). Análisis de la percepción del sistema normativo y sus repercusiones psicosociales en los futuros oficiales del Ejército Argentino. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Política, 12(37), 125-139. [ Links ]

Beramendi, M. & Zubieta, E. (2018). The factorial validation of the normative system perception scale: a proposal to analyze social transgression. Acta Colombiana en Psicología. 21(1), 249-259. doi: 10.14718/acp.2018.21.1.11. [ Links ]

Blanco, A. & Díaz, D. (2005). El bienestar social: su concepto y medición. Psicothema, 17(4), 582-589. [ Links ]

Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Descriptive Social Norms as Underappreciated Sources of Social Control. Psychometrika, 72(2), 263-268. doi:10.1007/s11336-006-1560-6. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E. & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being. Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 125(2), 276 - 302. [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., Fischer, R., & Coelho, J. A. P. (2009). Teoria funcionalista dos valores humanos: aplicações para organizações. RAM. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 10(3), 34-59. doi:10.1590/s1678-69712009000300004. [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., Fischer, R., & Santos, W. S. (2008). Teoria funcionalista dos valores humanos. In M. L. M. Teixeira (Ed.), Valores humanos e gestão: Novas perspectivas (pp. 47-80). São Paulo, SP: Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Comercial. [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., & Guerra, V. M. (2014). Functional theory of human values: Testing its content and structure hypotheses. Personality and Individual Differences, 60, 41-47. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.012. [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V., Santos, W. S. dos, Athayde, R. A. A., Souza, R. V. L. & Gusmão, E. É. da S. (2014). Valores, Altruísmo e Comportamentos de Ajuda: Comparando Doadores e Não Doadores de Sangue. Psico, 45(2), 209-218. doi:10.15448/1980-8623.2014.2.13837. [ Links ]

Gouveia, V., Milfont, T. L., Correa Vione, K. & Santos, W. S. (2015). Guiding Actions and Expressing Needs: On the Psychological Functions of Values. Psykhe (Santiago), 24(2), 1-14. doi:10.7764/psykhe.24.2.884. [ Links ]

Hervás, G., & Vázquez, C. (2013). Construction and validation of a measure of integrative well-being in seven languages: The Pemberton Happiness Index. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 66. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-66. [ Links ]

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: changing values and political styles among western publics. Nueva Jersey: Princenton University Press, [ Links ]

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social Well-Being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(2), 121-140. doi:10.2307/2787065. [ Links ]

Nino, C. (2005). Un país al margen de la ley. Buenos Aires: Ariel. [ Links ]

Rokeach, M.(1973). The nature of human values. NewYork: Free Press. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Díaz, D.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Blanco, A. & van Dierendock, D. (2010). Vitalidad y recursos internos como componentes del constructo de bienestar psicológico. Psico thema , 22(1), 63-70. [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Living well: a self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 139-170. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9023-4 [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141-166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [ Links ]

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719. [ Links ]

Sanchis, E. (1988). Valores y actitudes de los jóvenes ante el trabajo. Reis, 41, 131-151. doi:10.2307/40183314. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influence on altruism. En L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 221-279). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1-20. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1116. [ Links ]

Valle, M., Beramendi, M. & Delfino, G. (2011). Bienestar Psicológico y Social en jóvenes universitarios argentinos. REVISTA DE PSICOLOGÍA, 7(14), 7-26. [ Links ]

Zubieta, E., Muratori , M., & Fernández , O. (2012). Bienestar subjetivo y psicosocial: explorando diferencias de género. Salud & Sociedad, 3(1), 66-76. doi:10.22199/s07187475.2012.0001.00005 [ Links ]

Note:Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. L.S. has contributed in a,b,c,d; M.B. in a, c, d, e.

Correspondence: Maite Beramendi, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Argentina, Email maiteberamendi@gmail.com.

Received: October 26, 2018; Accepted: June 18, 2019

texto en

texto en