Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.13 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2019 Epub 01-Dic-2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i2.1889

Original Articles

Contributions from Psychology to communication in the health sector

1Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. España

2Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. España mpquevedoag @upsa.es, mhbenaventecu@upsa.es

Keywords: psychological intervention; healthcare professional-sick communication; bad news communication; Counseling

Palabras clave: intervención psicológica; comunicación profesional sanitario-enfermo; comunicación de malas noticias; Counseling

Introduction

Interacting as human beings has a preventive, supportive and healing value, which is essential for the development of our very sense of life. Without human relations we are merely rational animals with no prospects, capable of destroying ourselves and others (Bermejo, 2013). In recent years, several studies have been conducted to help people improve their relational capacity (Cibanal, 2013) and, above all, to enable them to communicate effectively according to the specific context of the situation.

This study is focused on reflecting on the importance of communication in a hospital and clinical setting, and how a good healthcare professional-patient relationship can provide a series of advantages both to the professional and to the patient. It is important to bear in mind that, from a user's perspective, there is a common perception that too many healthcare professionals seem to have forgotten about the non-physiological elements that form part of patients, only focusing on healing the person (Llubiá Maristany, 2008), without taking into account that the hospital stay, examination and treatment processes and, above all, news of declining health can all impact a person's well-being.

In an illness, it is clearly vital to consider how the patient is, so it is important for healthcare professionals to pay attention to this from the very outset. It must be taken into account that communication not only affects cognitive and emotional aspects, but it can also impact a patient's immune response, thus having a positive or negative effect on the development of an illness. (Borrás, 2003).

Our main objective is to make healthcare professionals understand that good communication in the healthcare professional-patient relationship has a series of causes and consequences, which can be both negative (when the healthcare professional is only concerned about alleviating the symptoms without considering how these symptoms affect the patient's life), and positive (in this case, communication skills will be used by the healthcare professional to foster a better relationship with the patient, not only treating the symptoms, but also aspects that impact the patient emotionally). Therefore, we will try to demonstrate that it is necessary to treat the “sick person” and not only the illness; that it is not only a question of curing physical aspects, but also of alleviating and promoting psychological aspects.

The importance of healthcare professional-patient communication

Healthcare professional-patient communication has been greatly overlooked compared to the great efforts devoted to evaluating the effectiveness of diagnostic instruments, and of surgical or pharmacological interventions and treatments (Borrás, 2003). The focus of healthcare professionals on healing, safety and their particular attention on the outcome, can sometimes lead them to neglect certain aspects such as communication, listening and interest in other non-physiological elements that form part of the person (Llubiá Maristany, 2008).

For this reason, Bayés (2004) states that it is essential for healthcare professionals to not only examine the patient's organism, but also the emotional, biographical and cultural circumstances that accompany their somatic symptomatology and biomedical history. In this respect, at points of the hospitalization in which the patient is feeling a wide range of negative emotions such as anguish or distress, non-verbal language takes prominence; this is why Peabody (1927) and Bayés (2004) state that healthcare professionals must learn how to observe their patients, learning how to examine not only their organism, but also their biography, words, facial expression and their circumstances.

Certain actions that weaken the healthcare professional-patient relationship and that are not beneficial for the latter have been analyzed in different studies, such as those conducted by Falvo and Tippy (1988) and Borras (2003), who concluded that during 38% of visits, patients received no explanation as to the amount of medication prescribed; during 50% they were not informed about how long their treatment would last, and healthcare professionals did not check that the patient had actually understood their indications; and possible obstacles with respect to therapeutic compliance were not examined, nor was the importance of a follow-up visit explained. Furthermore, Beckman and Frankel (1984) and Borras (2003), discovered that patients were interrupted on average 18 seconds after having started to answer the questions put to them by the healthcare professional. In the same vein, Suchman et al (1997) and Borras (2003) state that healthcare professionals do not always take potential opportunities to show empathy, in the case of verbal clues from patients, communicating their emotional distress.

Moreover, it seems that all too often patients feel like mere objects of study in university hospitals, and there has been debate surrounding the privacy of patients on one hand and, on the other, the need for students and healthcare professionals to carry out internships in order to acquire the necessary training to become good professionals in the future (Sánchez et al, 2003).

Another particularly important aspect for patients is waiting time, including: the waiting list to visit the specialist, waiting their turn to enter surgery or family members awaiting news on the condition of the patient in unexpected situations. It must be noted that subjective times are different to real times, (Campion, 2001; Bayés, 2004), and that subjective times are experienced differently by patients (suffering and uncertainty) compared to healthcare professionals (Bayés and Morera, 2000; Alvarado, 2003). Such suffering could be eased by good care from healthcare professionals. Cassell (1982) and Bayés (2004) emphasize that alleviating suffering and curing the illness must be valued as identical obligations by healthcare professionals who are truly devoted to patient care.

Through training methods in communication skills, we can help healthcare professionals to improve on these actions, given that, not only is it advisable but also ethically vital to address these aspects (Borras, 2003).

All medical acts are formed by three processes that take place in parallel: the physical care, the behavioral care and the cognitive and emotional care of patients. Therefore, the health outcome achieved will be influenced, simultaneously, by four types of response that must be borne by patients: the physical response to treatment (medication, surgery), their behavioral response (in terms of the therapeutic treatment, health-related behaviors), their cognitive response (beliefs about the illness and the treatment, expectations, perception of control) and their emotional response (anxiety, depression, animadversion).

In consultations, it is possible for healthcare professionals to both ease the symptoms of a certain health issue suffered by the patient, and to forge certain thoughts and emotions in the patient in relation to the illness and its treatment. In this respect, it has been discovered that healthcare professional-patient communication has significant clinical effects, both at cognitive and emotional level. (Borrás, 2003; Llubiá Maristany, 2008).

The information-communication process with the patient

Communication with patients is an essential and unavoidable activity. Therefore, there will always be a process in which the healthcare professional and the patient have to establish a type of communicative relationship; in this respect, the form of communication will depend on the type of relationship established by the professional with patients. (Benítez del Rosario and Asensio Fraile, 2002).

According to the proposals of Borrell i Carrió (1989) and Tazón Ansola, García Campayo and Aseguinolaza Chopitea (2002), in the clinical field there are four healthcare profiles when establishing “professional-patient” communication. We will describe each of them in detail below.

a.The “Technical model” is focused on the illness and neglects the psychosocial aspects of patients. Professionals use an aggressive style of communication in which the patient is not allowed an opinion, censoring possible criticism that could be made by the patient, and are cold when making recommendations or prescriptions. This means that patients do not feel that they are being well treated, leading to a lack of trust between the professional and the patient and, as a result, the latter does not accept the care offered by the healthcare professional, or follow their recommendations. Unfortunately, as stated by Tazón Ansola, García Campayo and Aseguinolaza Chopitea (2002), this model has been widely used.

b.Another model that has also taken prominence along with the previous one is the “Paternalistic or priestly model”, described by Benítez del Rosario, Asensio Fraile (2002) as the biomedical model in which there is a predominance of “little white lies” (covering up the truth about the health of the patient) and “communication focused on the professional”. In this model, healthcare professionals do take into account the biopsychosocial aspects of the patient, but they are only valued from the subjective perspective of the professional, who will decide what is best for the patient. Therefore, the individual values of the professional are imposed on patients, without taking into account their opinion or feelings. This model has been respected and demanded by society for years, but has recently come under criticism, specifically by patients with a certain cultural level. However, those who support this paternalistic style develop a high dependence on the professional, which provides beneficial effects to a certain extent.

c.The third model is the “Comradeship or complacent model”, which is common, although recent. Characterized by the absence of therapeutic distance, in this model the professional believes that the most important aspect is to get along with the patient. Unlike the previous model, the patient is the person who leads the situation, while the healthcare professional does not assume responsibility, letting the patient take the lead without placing any limits. (Tazón et al, 2002). The healthcare worker uses passive elements to communicate with the patient. The professional's main goal is to avoid conflicts at any cost and to allow everything requested of them. However, it also entails certain manipulation, for example, if the patient calls for more professional attitudes or therapeutic solutions, the professional would draw support from their good relationship to avoid accepting professional defeat.

d..And finally, the model that healthcare professionals are currently most advised to follow is the “Cooperative or contractual model”. As established by Tazón Ansola, García Campayo and Aseguinolaza Chopitea (2002), this model is totally focused on the importance of the emotions and feelings of the patient, without imposing intimate values. The professional accepts the opinion of patients, asking them to collaborate in their own care, providing opinions and selecting therapeutic options, but without ignoring their professional role and always acting as the expert. Thus, responsibilities are shared, as patients can decide what to do with their own health, while the professional remains within their role as expert. It is therefore a negotiation-based and assertive style; a good relationship is established between the professional and the patient, but the professional continues to be the expert, unlike the previous model. Consequently, as stated by Benítez del Rosario and Asensio Fraile (2002), it is a patient-focused communication model, which entails appropriate techniques to benefit the approach towards the private world of the individual.

Without a doubt, when communicating bad news, we recommend that the “Cooperative or contractual model” be used, given that it can facilitate quality communication, characterized by allowing patients to express their feelings and fears about their state of health, along with radiating emotional aspects that show patients that they will not be ostracized or neglected (Benítez del Rosario and Asensio Fraile, 2002).

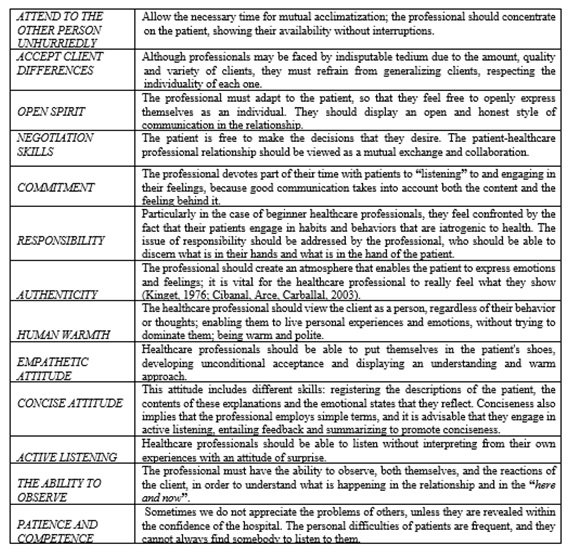

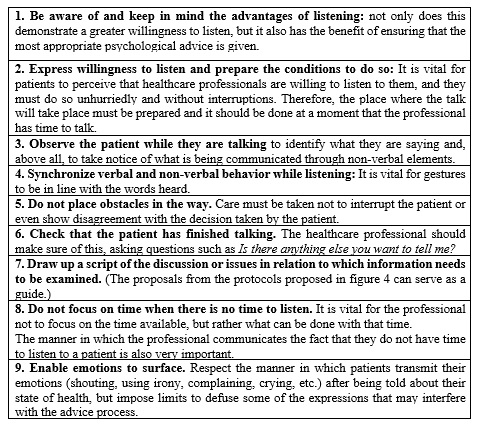

But, what do we mean by “good professional attitude”? Cibanal, Arce and Carballal (2003), demonstrate some of the appropriate attitudes, from a humanistic perspective, that should be adopted by healthcare professionals. (See Figure 1).

Communication of bad news

The communication process established between the healthcare professional and the patient is initiated through the clinical interview, which takes place within a situation in which the two start a conversation to address the health issues suffered by the patient, in order to clear up any doubts with regards to establishing a diagnosis and treatment (Rivera Rey, Veres Ojea, Rego González and Tuñez Lopez, 2016).

As established by Villa López (2007), communication, along with symptom examination and emotional support, are the basic tools used in the daily development of the work of healthcare professionals. A lack of skills when communicating the patient's diagnosis can lead to additional and unnecessary suffering for the patient when receiving information about their state of health, besides negatively affecting the healthcare professional-patient relationship. In this respect, healthcare professionals are in a complicated position due to their role as a health professional and the needs of the patient, meaning that bad news should be communicated in the most appropriate way possible. (Bukman, 1984; Almanza, 1999; Rabow and McPhec, 1999; Ayarra, 2001; Alves, 2003; Gómez, 2006; Núñez, 2006; Barreto, 2007; Bascuñán, 2007; Villa, 2007; Mirón, 2010; Rivera Rey, Veres Ojea, Rego González and Tuñez López, 2016).

Nevertheless, healthcare professionals can choose several different ways to face “complicated situations or conversations”; in any event, this should be done in a standardized manner and following a series of guidelines through what are known as “bad news communication protocols”. These guidelines have a series of objectives in common, as outlined by Bascuñán (2013):

a.Check what the patient knows and their expectations about their state of health.

b.Ascertain how prepared the patient is to hear the news, offering them a proportionate amount of information, depending on their state.

c.Provide emotional support, reducing the impact of the news and the feeling of distress.

d.Facilitate the patient's cooperation in a joint work plan.

Based on these protocols, especially with regards to the communication of bad news, healthcare professionals can create a style of relationship and communication with the patient, in which they can appropriately structure both the communication of the bad news, with the minimum possible damage, and the adaptation of the information given to each patient in relation to their resources (Arranz Carrillo, 2002). In this sense, the objectives are:

To reduce the huge psychological impact associated with this type of information.

To promote the assimilation and incorporation of the communication in the patient's cognitive frameworks.

To provide emotional support.

To facilitate the initiation of coping resources to aid the integration of the process.

To prevent the conspiracy of silence, promoting the revelation of the truth.

Action Protocols

Some of the protocols most widely used by healthcare professionals to communicate bad news to patients on their state of health are listed below:

The so-called SPIKES protocol (Buckman, 2005 and Mirón González, 2010), is one of the protocols that is most widely used and well-known by healthcare professionals. The name is formed by the initials of each of the stages to be followed when giving bad news. We will analyze each stage in detail below:

Setting: Bad news must be given in private, in the presence of the patient, family members or people close to the patient and the necessary members of the care team.

Perception of the patient: The healthcare worker should be aware of what the patient knows about their state of health before communicating bad news, for which open questions are usually used. If healthcare professionals take into account prior information in relation to the patient, they will be able to modify any inaccurate information and also personalize the information, depending on the patient's understanding, to achieve greater effectiveness.

Invitation: As stated by Rodríguez Salvador (2010), healthcare professionals should invite patients to ask everything they need to know, also enabling them to ascertain what really concerns the person; this is known as “bearable truth” (Mirón González, 2010), in the sense that the patient's individual pace must be respected.

Knowledge: In the case of a patient who wishes to receive the information, this is the moment to make them understand that they will be given bad news (if the patient does not want to hear it, the professional should move directly on to the therapeutic plan). There are three tasks to be performed during this stage (Arranz Carrillo, 2004): To decide on the objectives, to align with the patient and to inform.

Empathy: Once the patient has understood the information, a series of behavioral responses will usually be initiated, which can include: anxiety, fear, sadness, aggressiveness and ambivalence. The first step towards helping the patient is to validate, accept and understand these emotions; the patient basically needs to feel heard and understood.

Strategy and summary : After receiving bad news, Rodríguez Salvador (2010) determines that patients often feel lonely and uncertain, for which he proposes several procedures to reduce such anguish, consisting in: summarizing what has been discussed, lonely and uncertain, for which he proposes several procedures to reduce such anguish, consisting in: summarizing what has been discussed, checking what has been understood and formulating a work and follow-up plan.

The “ABCDE” protocol is based on five stages that are very similar to those of the “SPIKES” or “EPICEE” protocols (Rabow and McPhec, 1999 and Rivera Rey et al, 2016)

The “A” stands for: “Advance preparation”: Healthcare professionals have to pay attention to the physical space, but they also have to prepare themselves emotionally and mentally to give the bad news.

The “B” stands for: “Build a therapeutic environment/relationship” : This includes both steps 2 and 3 from the EPICEE and SPIKES protocols.

The “C” stands for: “Communicate well”: What is recommended during this stage is to “call things by their name”, avoiding the use of euphemisms.

The “D” stands for: “Deal with patient and family reactions”: The objective is to pay close attention to the emotional reactions of the patient, and provide emotional support.

The “E” stands for “Encourage and validate emotions: The professional's main role is to give realistic hope and to talk about the future.

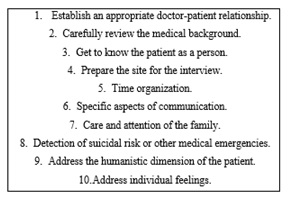

In addition, widely referenced and used today, Mirón González (2010) presents another protocol formed by 10 orientative points proposed by Almanza Muñoz in 1998and 1999, which serve as a guide to healthcare professionals when communicating bad news and which are as follows (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Protocol “10 points to be used as a guideline to communicate bad news”. (Source: Almanza Muñoz, J.J.; Holland, J.C, 1998, pp. 372-378)

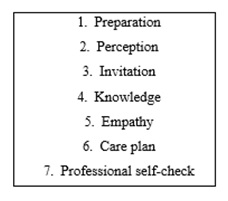

Finally, Villa López (2007) proposes a further protocol that follows the same steps as “EPICEE”, but with two differences: the sixth stage is named “care plan”, and she adds an extra point called “professional self-check”. Below, we will define these two new “stages”, “phases” or “points” proposed by this author. (Figure 3).

Sixth stage. “Care plan”: During this stage, the healthcare professional and the patient draw up a new care plan, based on the expectations hoped to be achieved: relieve symptoms and share fears and concerns.

Seventh stage. “Professional self-check”: The healthcare professional will self-examine the feelings and attitudes that emerged during the communication (flight, anguish, anxiety, fear...), subsequently identifying feelings that will enable them to improve in the development of their profession; and moreover, it will also help them to maintain good mental health, essential to avoid burnout.

The protocols that we have just described are like a game of insinuations, silent and indirect truths to help patients develop their own reality, always taking into account that the key issue is to communicate the bad news to the patient without destroying their hope, providing a climate of security and confidence. Healthcare professionals have to understand that it is difficult to find a balance and get it right every day. Drawing from science, their hearts and experience can bring them closer to achieving this (Arranz Carrillo, 2004).

Procedures and skills for communicating bad news in the Emergency Department

We have explained the most widely used ways of communicating bad news when giving information on a specific clinical diagnosis, but how should this be addressed when providing information in unexpected situations?

Ayarra and Lizarraga (2001) state that when family members are informed of an unexpected event, such as a death in an accident, a sudden serious illness, etc., it is advisable to use the “narrative technique”; that is, explaining everything that occurred from the very beginning. This narrative enables the brain of family members to gradually adapt to the new reality. These situations are becoming more frequent in our environment and cause immense suffering. Núñez, Marco, Burillo-Putze and Ojeda (2006) establish that 65% of unpredictable deaths happen in the emergency department and, because of this, hospital services must have professionals with a series of skills and attitudes who can inform the patient's companions in an appropriate fashion. Thus, they propose a series of guidelines to follow when facing such difficulties, taking into account that it is not possible to prepare in advance for the interactions following the death, so the healthcare professionals are the first ones who should be prepared. In this sense, it is advised:

If the patient's prognosis is death in the upcoming minutes, healthcare professionals should inform family members of what is happening, warning that the situation is critical, so as not to give rise to false hope.

If the patient has just died, healthcare professionals must use the narrative technique as described above, reporting the events occurred, the treatment provided and the patient's response, to ultimately communicate the bad news of the patient's death.

If the patient's relatives need to be contacted by telephone, the following elements should be taken into account:

Confirm that the appropriate person is on the phone.

Introduce yourself without initially using words such as “serious”, if family members do not know that the patient arrived unexpectedly.

Briefly describe the patient's situation, avoiding impacting terms such as “heart attack” or “accident”.

Advise the family member or members to go the emergency department as soon as they can so that a doctor can inform them more precisely about the patient's state.

Use a slow and calm tone of voice.

Furthermore, explaining what happened to the patient is extremely important when communicating the bad news. According to Issacs (2005) and Núñez, Marco, Burillo-Putze and Ojeda (2006), relatives will pay great attention to what is said and how it is said, and the message must be clear and the language accessible and understandable to family members, besides informing them that the patient has died, avoiding confusing words or expressions.

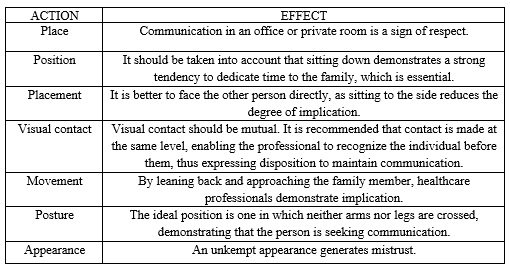

It is also necessary for the healthcare professional to take note of the non-verbal communication, taking into account, as stated by Hall (1989) and Núñez, Marco, Burillo-Putze and Ojeda (2006), that verbal communication forms 60% of the communication in total. These same authors have provided a series of expressions to be taken into account by healthcare professionals when providing information in unexpected situations (Figure 4).

Figure 4: “Certain expressions of non-verbal communication”. (Source: Núñez, S., Marco, T., Burillo-Putze, G., & Ojeda, J., 2006, pp. 581).

The communication of bad news will always be an unpleasant, but necessary, part of the clinical process. Nevertheless, healthcare professionals must do all they can (Johnston, 1992 and Villa López, 2007) to help individuals process their feelings, and to help family members to understand and accept the reactions of each one.

Communication in advanced oncology patients

A conspiracy of silence is considered to exist when information is withheld from a person who wants to know what is happening, and this is usually done to hide the diagnosis, prognosis and/or severity of the situation; it is often a habit of badly focused love (Barbero et al, 2005). As stated by Lizárraga Mansoa, Ayarra Elia and Cabodevilla Eraso (2006), the communication of information is a complex process for healthcare professionals and, furthermore, there are several factors to take into account when deciding whether to provide information or not:

There is a misconception that the patient will ask if they wish to receive information (Leydon ,2000 y Lizárraga et al 2006).

Healthcare professionals and family members believe that they know the desires and needs of patients (Bruera et al 2001 and Lizárraga et al 2006).

It must be taken into account (Lizárraga et al 2006) that the majority of families do not wish to inform the patient, as this information will take away their hope.

When faced with this new adaptation, family members need to protect themselves. The conspiracy demonstrates the obstacles experienced by family members when facing the suffering of what is happening and, in this sense, they need or want to deny it (Arranz et al, 2005).

However, it seems evident that it is necessary to communicate and transmit accurate information to oncology patients, for several different reasons: on one hand, due to the patient's legal right to be informed and, on the other, because the majority of patients are aware of the seriousness of their illness and imminent death, and if the people around them, both family members and healthcare professionals, deny and hide this fact, they have to experience their emotions and feelings alone, without being able to show and express their fears and concerns. In this respect, sharing information with the patient reduces their anxiety and enables them to lead a more normal life, aware of the advancement of their illness and imminent death. Furthermore, the help that can be provided by family members to the patient in this sense is also important (Lizárraga et al 2006).

With regards to the question about what information to provide, Arranz Carrillo y Barbero (2011) provide a series of guidelines that can help healthcare professionals when communicating with the patient and family members:

The information required by the patient at any given time.

Not only must the patient be informed about the diagnosis and prognosis of a particular illness, but also values and priorities must be established to include the patient in the decision-making process, enabling them to prepare for death.

Compare personal importance between quality and quantity of life.

Provide information about drawing up a living will.

Provide family members with information about caring for the patient.

Inform each family member of the advantages and disadvantages of hospitalizing the patient.

Another important aspect is the information that the healthcare professional believes the patient should know, in order to optimize their communicative and empathetic capacity. In this respect, Arranz Carrillo and Barbero (2011) propose a series of questions to facilitate the evaluation and dialog with this type of patients, and the subsequent emotional support (Arranz Carrillo, 2004):

Explore what the illness means to the patient

Recognize the coping method used by the patient

Inspect the patient's social support network

Define and prioritize problems

Evaluate spiritual resources

Identify psychological vulnerability

Identify the economic circumstances

Establish a relationship with professionals

Healthcare professionals should be aware that the patient is at the fore, and their difficulties should not hinder communication. Accompanying a patient in illness and in death requires great effort and stress at the beginning, because it means experiencing very intense emotions with the patient, the family and the healthcare professionals themselves (Lizárraga Mansoa, Ayarra Elia and Cabodevilla Eraso, 2006).

Furthermore, with regards to intervention with family members, and following the proposals of Watzlawick, Beavin Bavelas and Jackson (1987), it can be understood that interpersonal systems (such as family) can be explained as feedback loops, whether positive or negative, which influence the homeostasis of individuals and result in the system changing. Therefore, when a patient falls ill or is at the end of their life, this brings about changes in family members, who must do their part to ensure that the family system can become balanced once again.

Another open debate in relation to oncology patients and their family members is the question of who the most appropriate person is to transmit the bad news. In principle, the most appropriate person to communicate the news should be the physician who is responsible for the direct care of the patient, and who has the most complete/best information on the therapeutic process and the possible solutions, whether alone or in cooperation with other professionals on the medical team. Nevertheless, the importance of coordinating and defining roles within the health team must be noted: in other words, the patient and their family members often raise queries with different professionals and, for this reason, it is necessary to define who will be responsible for informing them, so that the answers are the same and there are no contradictions (Rassin et al, 2006; Mirón González, 2010).

Counseling in the healthcare field

Counseling (Rogers, 1977) originated in the clinical and hospital setting, as a way to address psychological aspects focused on individuals. It is now considered an essential technique to improve the “healthcare professional-patient” relationship in any pathological field (Bimbela, 2001; Arrnz et al, 2005 and Martí-Gil, Barreda-Hernández, Marcos-Pérez and Barreira-Hernández, 2013).

To conduct this process, the professional must accept the idea that health is a right or option of the user and not an obligation, and a series of essential skills must be developed, going well beyond the good communication skills that, naturally, a professional may have (Bimbela, 2001; Arranz et al, 2005). Therefore, healthcare professionals should train in the development and management of: Emotional skills, communication skills and motivation skills for behavioral change.

Emotional skills

The development of these skills is necessary to establish communication at the beginning, during and after professional interactions that take place, in order to manage any emotional alterations that may arise in the professional or in the patient and/or family members. The goal is to find solutions to ensure that these emotions do not overwhelm the professional or the patient, before selecting the alternative and acting. To achieve this, action should be taken with regards the three levels of human response that are at the origin and maintenance of emotions: cognitive level, physiological level and motor level. They are described briefly below.

a.Firstly, intervention at cognitive level influences the patient's interpretation of a situation. The healthcare professional must ensure that the individual duly interprets the new situation, without any kind of cognitive distortion. If cognitive distortions do appear, they will prevent the patient from seeing the reality objectively, thus blocking any attempted solution (Beck, 1962, 1995).

b.It is also essential to intervene at physiological level, as the vegetative system is probably altered after having received the news as threatening, stressful or unpleasant. Having activated the nervous system, if it is maintained for an excessive amount of time, or is activated at very high levels, it can lead to both deteriorated cognitive and motor levels, and the reduced ability of patients to duly confront their state of health. Tazón et al (2002) propose that to duly adapt to and confront the new situation, both active strategies, distraction strategies and attention diversion strategies should be used.

c.The motor or behavioral level also requires action: faced with a powerful and unexpected situation, it is very probable that the patient does not know how to act appropriately.

Communication skills

The healthcare professional must pay attention both to the words used and the accompanying gestures, as everything that they do and do not do is part of communication (Watzlawick, 1967). Among the central elements in human communication, we will focus mainly on active listening and empathy.

a.We will start with active listening. How can the healthcare professional listen actively and with attention, in a manner in which the patient realizes that this is being done? Costa Cabanillas, López Méndez (2008) propose nine essential rules when implementing active listening (Figure 5). Through listening, healthcare professionals can encourage patients to talk and discuss what they feel. They can thus ascertain the patient's perception of the new situation, reducing perceptual bias and promoting a climate of dialog and negotiation on the possible alternatives to be considered (Costa Cabanillas, López Méndez ,2008).

b.Not only is active listening important, but it must also be accompanied by empathy. Rogers (1980) was the first author who underlined the importance of empathic understanding as an essential requirement in establishing the therapeutic relationship. According to this author, it entails the precise observation of the feelings experienced by the patient and of what they mean to them and, once observed, communicating them through messages that contain an emotional component towards the patient. (Costa Cabanillas, López Méndez, 2008).

Figura 5: Nine rules to facilitate active listening. (Source: Costa, M. & López Méndez, E., 2003, pp. 133-135)

Motivation skills for behavioral change

The main goal of these skills is to encourage patients to correctly follow the alternative that they have chosen (Adherence to the treatment). As this is something that will be done by the patients themselves, it is important that the healthcare professionals have previously acknowledged the freedom of choice surrounding the therapeutic objectives as a way of increasing patient motivation. (Thornton, Gottheil, Gellens and Alternan, 1977; Sánchez -Craig and Lei, 1986; Miller and Rollnick 1999).

We will focus on how to develop these skills in order to create motivation towards changing the patient's behaviors and habits. Bimbela (2001) proposes the P.R.E.C.E.D.E model (an adaptation of that proposed by Green, 1991).

a.Firstly, it is necessary to ascertain the predisposing factors that are related to the individual's motivation to engage in the behavior that is to be promoted; analyzing the attitudes and opinions of the patient towards the treatment, and ensuring that the patient's values and beliefs are in line with the steps being taken.

b.Analysis of the enabling factors is also vital. In this way, the healthcare professional can ascertain the patient's skills and abilities to engage in the behavior.

c.And finally, healthcare professionals must pay particular attention to reinforcing factors. They have to ascertain what a particular therapeutic action means to the patient: how it affects their social environment, family, themselves, the physical and emotional benefits or disadvantages obtained and the resulting consequences.

If these interpersonal skills are correctly developed, the processes of influence of the healthcare professional become effective in promoting the essential objectives of counseling: acceptance, support, validation, empowerment and change (Costa Cabanillas, López Méndez, 2008). Furthermore, counseling benefits both the healthcare professional, who can work in a more effective and satisfactory manner, and the patient, who feels better cared for, more satisfied and more motivated to engage in healthy behaviors, benefiting healthcare institutions, which can make a more rational use of services and pharmaceuticals, while promoting and maintaining healthier lifestyles (Bimbela, 2001).

Conclusions

Establishing good communication between healthcare professionals and patients is not only beneficial to improving the life and emotional welfare of the patient, but it also contributes to enhancing the final curative effectiveness of biomedical interventions, and the effectiveness and efficiency of the health system.

It is essential for healthcare professionals to be trained in the correct development of their communication skills, enabling them to establish a good healthcare professional-patient relationship, given that, as we have seen, the use of good communication can lead to an improved emotional state, the eminent psychological acclimatization of patients and greater capacity to cope with the deterioration of their state of health. Therefore, not only must they have clinical knowledge, but they must also be able to identify the necessary skills that must be developed in order to strengthen the relationship and communication with the patient.

Furthermore, it is essential to introduce counseling in the healthcare field for several different reasons: when healthcare professionals effectively develop emotional, communication and motivational skills, not only can they achieve an improved relationship with their patient, but it also entails benefits for both; the former, as they feel greater satisfaction in their work, as they work more efficiently and observe better results in the behavior of their patients; and the latter, as not only do they achieve greater autonomy, by making decisions and taking action in relation to their own health, but long-lasting changes can also be observed in their behavior and lifestyle, preventing iatrogenesis, thanks to the knowledge and recommendations of the healthcare professional, who encourages them to reflect.

During university training processes, it is vital to instill the importance of avoiding such learning shortages in healthcare professionals, to ensure that they can duly manage the psychological reactions that emerge in communication with patients.

Therefore, it is fundamental for healthcare professionals not only to care for the physical side of patients, but also their emotions, concerns and feelings, learning a series of skills to improve communication with the patient, also resulting in greater quality in the healthcare professional-patient relationship and in improved perception of health systems.

REFERENCES

Almanza Muñoz, J.J. & Holland, J.C. (1998). La comunicación de las malas noticias en la relación médico paciente. Guía clínica práctica basada en evidencia. Revista Sanidad Militar, 52(6),372-378. [ Links ]

Arranz Carrillo, P. (2004). Información y comunicación con el enfermo como factor de prevención del dolor y el sufrimiento: La acogida. Dolor y sufrimiento en la práctica clínica, (2) ,127-137. [ Links ]

Arranz, P. & Barbero, J. (2011). Modulo comunicación, gestión emocional y duelo. XII edición Master Cuidados Paliativos UAM: 1- 57 [ Links ]

Ayarra, M. & Lizarraga, S. (2001). Malas noticias y apoyo emocional. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra, 24(2): 55-63 [ Links ]

Barbero, J., Barreto, P., Arranz, P., & Bayés, R. (2005). Comunicación en oncología clínica. Madrid: Just in Time/Roche Farma. [ Links ]

Bascuñán, M.L. (2013). Comunicación de “malas noticias” en salud. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 24(4) ,685-693. [ Links ]

Bayés, R. (2004). Alivio o incremento del dolor y el sufrimiento en el ámbito hospitalario: pequeños esfuerzos, grandes ganancias. Dolor y sufrimiento en la práctica clínica , 1, 113-125 [ Links ]

Benítez del Rosario, M.A. & Asensio Fraile, A. (2002). La comunicación con el paciente con enfermedad en fase terminal. Atención Primaria, 30(7) ,463-466. (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0212-6567(02)79073-2) [ Links ]

Bimbela, J.L. (2001). El Counselling: una tecnología para el bienestar del profesional. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra , 24(2) ,33-42. [ Links ]

Borrás, F. (2003). La comunicación médico enfermo como posible factor de mejoría o yatrogenia: psicoconeuroinmunologia (http://www.terapianeural.com/images/stories/basic/COMUNICACION_MEDICO-PACIENTE.pdf ) [ Links ]

Cibanal Juan, L., Arce Sánchez, M., & Carballal Balsa, M. (2003). Técnicas de comunicación y relación de ayuda en Ciencias de la Salud. Madrid: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Costa, M. & López Méndez, E. (2003). Consejo psicológico. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis. [ Links ]

Llubià Maristany, C. (2008). El poder terapéutico de la escucha en medicina crítica. Humanitas Humanidades Médicas, 27, 13-27. (http://www.iatros.es/wp-content/uploads/humanitas/materiales/TM27.pdf) [ Links ]

Martí-Gil, C., Marcos-Pérez, G. & Barreira-Hernández, D. (2013). Counselling: una herramienta para la mejora de la comunicación con el paciente. Farmacia Hospitalaria, 37(3), 236-239. [ Links ]

Miller, W. & Rollnick, S. (1999). La Entrevista motivacional: preparar para el cambio de conductas adictivas. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Mirón González, R. (2010). Comunicación de malas noticias: perspectiva enfermera. Revista española de comunicación en salud, 1(1) ,39-49. [ Links ]

Núñez, S., Marco, T., Burillo-Putze, G. & Ojeda, J. (2006). Procedimientos y habilidades para la comunicación de las malas noticias en urgencias. Medicina Clínica, 127(15) ,580-583. [ Links ]

Rivera Rey, A., Veres Ojea, E., Rego González, F. & Túnez López, J.M. (2016). Análisis de la formación en comunicación y la relación médico-paciente en los grados de Medicina en España. Índex Comunicación, 6(1), 27-51 [ Links ]

Rodríguez Salvador, J. (2010). Comunicación Clínica: Cómo dar Malas Noticias. (http://doctutor.es/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Dar-Malas-Noticias-JJ-Rodriguez-S-2010.pdf) [ Links ]

Rogers, C.R. (1972). Proceso de convertirse en persona: mi técnica terapéutica. Barcelona: Paidós . [ Links ]

Tazón Ansola, M.P., García Campayo, J., & Aseguinolaza Chopitea, L. (2002). Relación y comunicación. Madrid: Difusión Avances de Enfermería. [ Links ]

Villa López, B. (2007). Recomendaciones sobre cómo comunicar malas noticias. Nure Investigación, 1, 31. (http://www.nure.org/OJS/index.php/nure/article/view/355/346) [ Links ]

Watzlawick, P., Jackson, D., & Bavelas, J. (1987). Teoría de la comunicación humana: interacciones, patologías y paradojas. Barcelona: Editorial Herder. [ Links ]

Note: Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. M.P.Q.A. has contributed in a,d,e; M.H.B.C. in a,d,e.

Correspondence: María Paz Quevedo Aguado, Facultad de Psicología. Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, Nº 5. 37002. Salamanca (España). E-mail: mpquevedoag @upsa.es. María H. Benavente Cuesta, e-mail: mhbenaventecu@upsa.es

Received: February 26, 2018; Accepted: May 02, 2019

texto en

texto en