Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.13 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2019 Epub 01-Dic-2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i2.1886

Artículos Originales

Psychometrics characteristics of the child and adolescent perfectionism scale in primary school students in Chile

1 Universidad del Bio-Bio. Chile cossa@ubiobio.cl, marce.ing.est@gmail.com, nlagos@ubiobio.cl, mpalma@ubiobio.cl, sperez@ubiobio.cl

Key words: perfectionism; psychometric; primary education; personality; psychology

Palabras clave: perfeccionismo; psicometría; educación primaria; personalidad; psicología

Introduction

Perfectionism has been understood as a relatively stable personality trait over the years. Within psychology and psychiatry, it has been considered as one inherent to populations of individuals with some personality disorders, linked to a pathologizing tendency and focused on therapeutic treatment around irrational beliefs (González, Gómez and Conejeros, 2017). However, based on research from the last ten years (Damian et al., 2013; Herman, Wang, Trotter, Reinke and Lalongo, 2013; Maia et al., 2011; McGrath et al., 2012; Sherry et al. , 2013), it is now considered a relevant psychological factor due to the fact that it acts as a reference point in the treatment of various psychopathologies.

This characteristic is no longer only considered as a one-dimensional concept and a secondary symptom of specific pathological conditions, but as a complex and multidimensional personality trait, which may also be related to adaptive mechanisms, where it plays a relevant role in personal development related to motivation and perseverance (González et al., 2017).

In relation to the above, perfectionism is defined as the tendency to establish high performance standards in combination with an excessively critical evaluation of them, and a growing concern about making mistakes (Galarregui and Keegan, 2012). In addition, the importance of perfectionism in the academic field has also been pointed out, by addressing the fact that such characteristic is not only widely present in adult students but also, significantly and with temporary stability, in elementary students, as reported by studies in the Spanish population (Vicent, 2017). Perfectionism is evidenced in the academic field through behaviors such as meticulousness in the study, an excessive concern for obtaining high levels of performance, and a concern about not failing in academic areas.

Apparently, there is a relationship between perfectionism and other psychoeducational variables that would allow the reduction of its maladaptive characteristics, which have also proven to be effective in reducing other psychological disorders (Aldea, Rice, Gormley and Rojas, 2010; Arpin-Cribbie, Irvine and Ritvo, 2012; Arpin-Cribbie et al., 2008; Fairweather and Wade, 2015; LaSota, 2008; Wilksch, Durbridge and Wade, 2008). On this basis, it is suggested that strengthening the adaptive characteristics of perfectionism could strengthen academic achievement skills.

In line with the above, González et al. (2017) point out in a study conducted with Chilean students, that adaptive perfectionist subjects showed a more prosperous view of the environment, considering it as an inexhaustible source of enriching experiences that contribute to their personal development.

On the other hand, maladaptive perfectionism could have a negative impact on academic performance, is associated with various disorders and contributes to psychological fatigue and even abandonment of studies at the university level. These characteristics are probably related to the burnout syndrome, as the difficulty to reach high expected levels of performance would increase the anguish and could generate depressive symptoms (Arana et al., 2014).

Child-adolescent Perfectionism Scale

Research on perfectionism has been largely developed in young and adult population, leaving a gap in the knowledge of how perfectionism is measured and modeled in the early development stages (Vicent, 2017). Even though perfectionism was originally conceptualized as a one-dimensional construct, it is currently considered as a multidimensional concept that has both personal and social components, present not only in adults but also in children.

According to Flett et al. (2016) there is a growing interest in perfectionism among children and adolescents, as well as a growing interest in measures designed to evaluate perfectionism in young people. The results of their research support the use of CAPS and the notion that vulnerable children and adolescents who are perfectionists are under considerable pressure to meet expectations, which could lead to negative emotional and health situations.

Vicent (2017) found six instruments that allow the assessment of the level of childhood perfectionism, which considers between 2 and 7 factors, presenting good psychometric properties in general. Among them, the Child-Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS) stands out due to the fact that it is one of the most commonly used, and it is also the only scale in which temporal consistency is reported.

Flett, Hewitt, Boucher, Davidson and Munro (2000) developed the Child-adolescent Perfectionism Scale, which includes 22 items and contemplates two dimensions, Socially Prescribed Perfectionism (SPP), which is considered more misfit, and self-oriented Perfectionism (SOP), which constitutes a more adaptive construction. As perfectionism is associated with psychological distress in clinical and non-clinical populations, it is necessary to strengthen its adaptive dimension (Bento, Pereira, Saraiva and Macedo, 2014).

The internal consistency scores were α = 85 for SOP and α = 81 for SPP. The test-retest analysis with a five-week interval showed adequate temporal stability coefficients that ranged between .66 and .74 for the dimensions of SOP and SPP, respectively. Likewise, the authors discovered sexual differences, in favor of men, in the mean scores of the SPP dimension (Vicent, 2017).

In addition, the temporal structure of the scale has been reexamined, in instances where there was a coincidence with the original structure of two factors (O'Connor, Dixon and Rasmussen, 2009); even though statistically adequate indices have also been found in models of three and four factors (Vicent, 2017). In relation to this, O'Connor et al. (2009) conducted an instrument analysis and suggested a solution of 3 factors (that is, socially prescribed perfectionism, effort self-oriented perfectionism and criticism self-oriented perfectionism).

These authors validated their 3-factor model in an independent replication sample (n = 514) and confirmed that the 3-factor structure was invariant based on sex and time (test-retest for 6 months). Taking these analyzes together, the authors concluded that their discriminant structure of 3 factors is withstanding (O’Connor et al., 2009).

Vicent (2017) also performs a validation of the instrument in a sample of 1809 Spanish children (ages 8 to 11 years old) maintaining all three factors. However, she decreases the number of items of the instrument to 14, unlike the other authors who maintained the original number of 22 items. In addition, she points out that the instrument has good indicators of reliability at global level (a = .80) and in its dimensions (.70 to .75).

Therefore, despite great development of the subject in the psychoeducational field, there are few experiences of implementation and validation of the instrument in the Chilean school population, which does not allow the exploration of the behavior of this variable in said population. Thereby, the aim of this study is to validate a Chilean adaptation of said instrument, by analyzing the psychometric characteristics that it presents in a population of primary school students in Chile.

Participants

1195 students from educational establishments, both municipal and private, from the Ñuble province of Chile participated in the study; the ages of the participants ranged from 10 to 17 years old (M = 12.5; D.E. = 1.38); 46% were men (550), while 54% were women (645). The students were in fifth (19%), sixth (23%), seventh (29%) and eighth grade (29%).

Instruments

The instrument used was the Child-adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS) of Flett et al., (2000) adapted by Vicent (2017) to a Spanish population. However, the items writing was adapted to the Spanish used in Chile. The original instrument consists of 22 items and has, according to Vicent, a good overall consistency level (α = .80) just as in the factors she found (α between .70 and .75). The answers are distributed on a Likert scale of five alternatives (completely disagree, slightly agree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly disagree and completely disagree).

Ethical considerations

The research project and its instruments were reviewed and endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the Research Directorate of the Universidad del Bio-Bio.

Procedures

The process began by contacting educational establishments through their principals, who selected a teacher to coordinate the implementation of the instrument. In each course parents of children and teenagers were informed and they were also requested to give an informed consent of the participation of the students; the implementation of the instrument was carried out in a classroom of each course, at a time given by the teachers. Once the instruments were tabulated, a database was generated, which was then analyzed with the SPSS V. 21 program, applying an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to determine the number of factors in the instrument, as well as Cronbach's alpha to determine the global reliability of the instrument and of its factors. Finally, descriptive statistics (measures of central tendency and dispersion) were applied.

Results

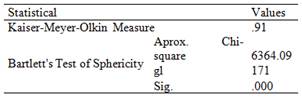

The Exploratory Factor Analysis (AFE) considers Pearson's correlation matrix among the 22 items. The extraction method considered was that of Maximum Likelihood and Varimax rotation. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy measure resulted in a value equal to 0.907, which is satisfactory (Lloret-Segura, Ferreres-Traver, Hernández-Baeza and Tomás-Marco, 2014) and indicates that there is a strong interrelation between the items of the instrument. Bartlett's sphericity test indicates, according to the results obtained (Chi-square = 6609.167, gl: 231, p-value = .000 <.05), that the established null hypothesis is rejected, which stipulated that the data matrix is equal to an identity matrix and therefore there would be no collinearity (Table 1). With respect to the number of axes to retain, the latent root criterion, which leaves those factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, indicates that three factors must be retained, as from the fourth factor a linearity is formed in the trend; these first three factors explain 46.31% of the variance of the original data.

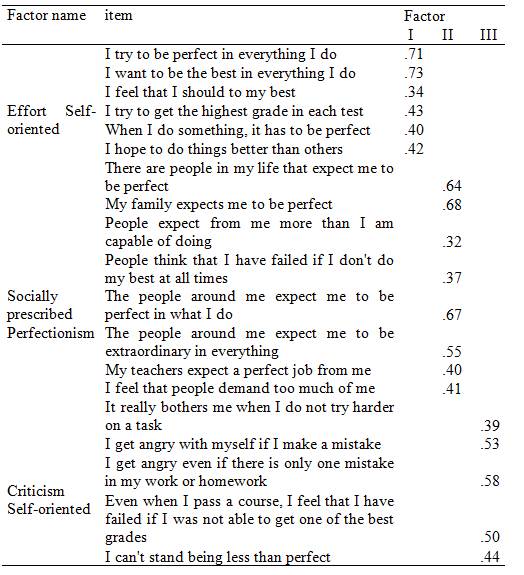

Table 2 shows the matrix of components rotated using the Varimax method. In addition, in the matrix, the factorial loads (correlation between each of the items and the factors) are presented, in this way, it is possible to determine the main factors of the instrument, which refers to those factors that present a factorial load greater than .3. This establishes an adequate relation between the item and each factor, except for items 3, 9 and 18, which report the lowest factor load. Some items (3, 9, 11, 18, and 19) also present a load in two different factors, which was clarified by determining the higher load (more than one point). However, items 3, 9 and 18 presented differences lower than the established, so it was decided to eliminate them. The three factors and their items were related to the factors indicated in the study of Vicent (2017), and they were distributed in a relatively homogeneous.

Table 2: Exploratory Factor Analysis with three components rotated with the Varimax method with Kaiser

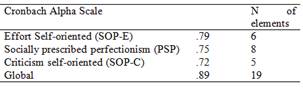

In addition, an analysis of reliability, in which the latter was understood as the internal consistency of the items of an instrument, was applied. This analysis allows studying the properties of the measurement scales and the items that comprise it, and providing information about the relationships between the latter. Reliability as internal consistency of the global questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, which resulted in a value equal to 0.89, considered suitable according to the criteria of the authors George and Mallery (2003).

The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the Effort Self-Oriented Factor has a value equal to 0.79, the Criticism Self-Oriented Factor (PAO-C) value is 0.72, and the Socially Prescribed Perfectionism (PSP) value is equal to 0.75; the coefficients obtained are considered acceptable (George and Mallery, 2003), (Table 3).

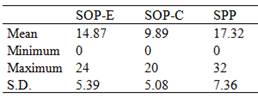

Finally, the overall result of the students in the instrument was analyzed, finding that effort self-oriented perfectionism registers an average response of 14.87, which would correspond to 61.9% of the total value of the scale score; while criticism self-oriented perfectionism registers an average of 9.89 that would correspond to 49.5% of the value of the scale score. Socially prescribed perfectionism registers an average of 17.32, reaching 54% of the total value of the scale score (Table 4).

Thus, it can be inferred that effort-oriented perfectionism is the type of perfectionism that displays the greatest development in the students, while criticism-oriented would be the least developed.

Discussion

The research of perfectionism as a factor that affects the development of people is an underdeveloped area in Chile. However, in recent years, there has been a greater interest on its research, especially regarding its relationship with academic factors (González et al., 2017). Although there are different instruments that enable the evaluation of perfectionism, the CAPS test has shown good statistical indicators as well as temporal consistency, which is useful in the study of different cohorts of students, and makes it possible to work with children from the age of 8 years old (Vicent, 2017 ).

Although there are few studies of perfectionism in the Chilean school population (Albornoz, 2016; Correa, Zubarew, Silva and Romero, 2006), the measurement of perfectionism has been carried out indirectly, through subfactors of scales of eating disorders or attentional deficits, and a specific scale that evaluates the construct has not been applied. This is important because there are no studies available in Chile that show the psychometric characteristics of the CAPS perfectionism scale, thus, the results derived from this research could be a good starting point for its use in the country.

The results obtained in this study are presented in a similar way to the validation studies made in Spanish samples, showing the existence of three factors after the construct, and also associating almost the same items to those factors. The Spanish implementation, however, makes a significant reduction of items to achieve greater reliability, ending with 13 items. Although a reduction of items was made in the present study, in comparison, it was quite minor, which allowed an instrument of 19 items.

In addition, it is also observed that the level of reliability of the global instrument was good, and reached a level somewhat higher than the research carried out in the Spanish sample; the factors encountered also have an adequate level of reliability. In light of the above, the results would indicate that an adequate instrument can be available for the study of perfectionism in elementary school students.

On the one hand, at a descriptive level, it is observed that effort-oriented perfectionism (SOP-E) would present the greatest development in the students who participated in the study, which would indicate that behaviors related to commitment to tasks and to make an effort to perform activities are valued. On the other hand, criticism self-oriented perfectionism (SOP-C), showed a minor development among the participants, which would be more related to the assessment of the demands rather than of the achievements. These two factors represent the internal facet of the construct, that is, they are autonomous manifestations of the phenomenon, which in some sense is related to the locus of internal control (Vicent, 2017). As for socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP), it showed a lower score than the other factors in the sample, which is valued as positive since this would be an external manifestation, related to society's demands, which are difficult to control and more iatrogenic.

In this sense, the panorama presented among students is positive since effort-oriented perfectionism is one of the positive aspects of this process (Arana et al., 2014; Vicent, 2017), which would imply that the students would have a high evaluation of effort and would be motivated to carry out activities while paying more attention to the satisfaction of performing the tasks, than to self-imposed demands or to demands established by the social environment, which could be positive to the development of autonomous behavior.

Conclusions

The study conducted on specifying the psychometric characteristics of the CAPS test presented good results and maintained a coherence in the structure of factors and items that the Spanish implementation, the closest to Chile’s reality, had presented.

To be able to have an instrument with good reliability indicators, in the area of primary education in Chile, is an important step as there are few studies on this subject, as well as few instruments that directly account for the local reality. This would allow not only to obtain information regarding the presence of perfectionism in Chilean elementary students, but also to be able to relate this characteristic to educational variables that can help students’ development.

The sample selection is considered as a limitation of the study, as it focused only on one region of the country, and due to the fact that its design was not randomized. This implies that the data cannot be generalized and that normative standardized profiles for the population also cannot be obtained.

Finally, as a projection of the research, we take into account the need to apply the instrument to a sample that incorporates a greater number of students who also come from different sectors of the country, as well as from different socio-cultural environments. In addition, it is necessary to proceed with the concurrent validation, relating this instrument with similar ones to obtain a valid construct.

Ackowledgment:

Project code GI 160823-EF for research groups, supporting by Research Department of Bío-Bío University, Chile.

REFERENCES

Aldea, M. A., Rice, K. G., Gormley, B. & Rojas, A. (2010). Telling perfectionists about their perfectionism: effects of providing feedback on emotional reactivity and psychological symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy 48, 1194-1203. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.003 [ Links ]

Albornoz, E. (2016). Desatención e Hiperactividad y Variables Socio- demográficas en Población Adolescente Chilena. Tesis para optar al grado de Doctor en Salud Mental. Universidad de Concepción, Chile. Disponible en: http://repositorio.udec.cl/bitstream/handle/11594/1989/Tesis_Desatencion_e_Hiperactividad_y_Variables.Image.Marked%20-%201.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Arana, F. G., Galarregui, M. S., Miracco, M. C., Partarrieu, A. I., De Rosa, L., Lago, A. E., Traiber, L. I., …. & Keegan, E. G. (2014). Perfeccionismo y desempeño académico en estudiantes universitarios de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 17(1), 71-77. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2014.17.1. [ Links ]

Arpin-Cribbie, C. A., Irvine, J. & Ritvo, P. (2012). Web-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for perfectionism: a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 22(2), 194-207. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.637242 [ Links ]

Arpin-Cribbie, C. A., Irvine, J., Ritvo, P., Cribbie, R. A., Flett, G. L. & Hewitt, P. L. (2008). Perfectionism and psychological distress: a modeling approach to understanding their therapeutic relationship. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26, 151-167. doi: 10.1007/s10942-007-0065-2 [ Links ]

Bento, C., Pereira, A., Saraiva, J. & Macedo, A. (2014). Children and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale: Validation in a Portuguese Adolescent Sample. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 27(2), 228-232. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201427203 [ Links ]

Correa, V., María Loreto, Zubarew, G., Tamara Silva, M. Patricia, & Romero S, María Inés. (2006). Prevalencia de riesgo de trastornos alimentarios en adolescentes mujeres escolares de la Región Metropolitana. Revista chilena de pediatría, 77(2), 153-160. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0370-41062006000200005 [ Links ]

Damian, L. E., Stoeber, J., Negru, O. & Baban, A. (2013). On the development of perfectionism in adolescence: perceived parental expectations predict longitudinal increases in socially prescribed perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 688-693. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.021 [ Links ]

Fairweather, A. K. & Wade, T. D. (2015). Piloting a perfectionism intervention for preadolescent children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 73, 67-73. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.004 [ Links ]

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Boucher, D. J., Davidson, L. A. & Munro, Y. (2000). The Child Adolescent Perfectionism Scale: development, validation, and association with adjustment. Manuscrito inédito, York University: Toronto, Ontario, Canadá. [ Links ]

Flett, G., Hewitt, P., Besser, A., Su, Ch., Vaillancourt, T., Boucher, L. & Gale, O. (2016). The Child-Adolescent Perfectionism Scale: Development, Psychometric Properties, and Associations With Stress, Distress, and Psychiatric Symptoms. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(7), 634 - 652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916651381 [ Links ]

Galarregui, M. & Keegan, E. (2012). Perfeccionismo y procrastinación: relación con desempeño académico y malestar psicológico. Estado del arte. IV Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XIX Jornadas de Investigación VIII Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. Facultad de Psicología - Universidad de Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th Ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

González, A., Gómez-Arízaga, M. P. & Conejeros-Solar, M.I. (2017). Caracterización del Perfeccionismo en Estudiantes con Alta Capacidad: Un Estudio de casos exploratorio. Revista de Psicología, 35(2), 581-616. doi: https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.201702.008 [ Links ]

Herman, K. C., Wang, K., Trotter, R., Reinke, W. M. & Lalongo, N. (2013). Developmental trajectories of maladaptive perfectionism among African American adolescents. Child Development, 84(5), 1633-1650. doi 10.1111/cdev.12078 [ Links ]

LaSota, M. T. (2008). A cognitive-behavioral-based workshop intervention for perfectionism. Nevada: Edic. Universidad de Nevada [ Links ]

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A. & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de psicología, 30, 1151-1169 [ Links ]

Maia, B. R., Soares, M. J., Pereira, A. T., Marques, M., Bos, S. C., Gomes, A., & Macedo, A. (2011). Affective state dependence and relative trait stability of perfectionism in sleep disturbances. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 33(3), 252-260. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462011000300008 [ Links ]

McGrath, D. S., Sherry, S. B., Steward, S. H., Mushquash, A. R., Allen, S. L., Nealis, L. J. & Sherry, D. L. (2012). Reciprocal relationships between self-critical perfectionism and depressive symptoms: evidence from a short-term, four-wave longitudinal study. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44(3), 169-181. doi: 10.1037/a0027764 [ Links ]

O'Connor, R. C., Dixon, D., & Rasmussen, S. (2009). The structure and temporal stability of the Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 437-443. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016264 [ Links ]

Sherry, S. B., MacKinnon, A. L., Fossum, K. L., Antony, M. M., Stewart, S. H., Sherry, D. L. & Mushquash, A. R. (2013). Perfectionism, discrepancies, and depression: testing the perfectionism social disconnection model in a short-term, four-wave longitudinal study. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 692-697. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.017 [ Links ]

Vicent, M. (2017). Estudio del perfeccionismo y su relación con variables psicoeducativas en la infancia tardía. Tesis para optar al grado de Doctor en Investigación Educativa. Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, España [ Links ]

Wilksch, S. M., Durbridge, M. R. & Wade, T. D. (2008). A preliminary controlled comparison of programs designed to reduce risk of eating disorders targeting perfectionism and media literacy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 939-947. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799f4a [ Links ]

Note:Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. C.O.C. has contributed in a,b,c,d,e; M.L.F. in b,c,d; N.L.S.M. in a,d,e; M.P.L. in b,d,e; J.S.P.N. in b,d,e.

Correspondence: Carlos Ossa-Cornejo. Universidad del Bio-Bio. Av. Andrés Bello # 720, Casilla postal 447, Chillán, Chile; e-mail: cossa@ubiobio.cl. Marcela López-Fuentes; e-mail: marce.ing.est@gmail.com. Nelly Lagos-San Martín; e-mail: nlagos@ubiobio.cl. Maritza Palma-Luengo; e-mail: mpalma@ubiobio.cl. José Samuel Pérez-Norambuena; e-mail: sperez@ubiobio.cl

How to cite this article: Ossa-Cornejo, C., López-Fuentes, M., Lagos-San Martín, N., Palma-Luengo, M., Pérez-Norambuena, J.S. (2019). Psychometric characteristics of the child-adolescent perfectionism scale (CAPS) in elementary school students of Chile. Ciencias Psicológicas, 13(2), 296 - 304. doi: 10.22235/cp.v13i2.1886

Received: March 08, 2018; Accepted: May 02, 2019

texto en

texto en