Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.13 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2019 Epub 01-Dic-2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i2.1877

Original Articles

Routes and collisions at work care for women victims of violence in Spain

1 Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristóvão. Brasil psimulti@gmail.com, joilsonp@hotmail.com

2Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. España ptt.alicia@gmail.com, leonor.cantera@uab.cat

Key words: health personnel; self-care; battered women; working conditions; workplace violence

Palavras chave: profissionais da saúde; autocuidado; mulheres agredidas; condições de trabalho; violência no local de trabalho

Palabras clave: profesionales de la salud; mujeres maltratadas; autocuidado; condiciones de trabajo; violencia en el trabajo

Introduction

The organization of laws to combat violence against women in Spain is a fact established in compliance with recommendations to combat this reality by international organizations, such as the UNO (United Nations Organizations). Thus, this effort was promoted in the Spanish context by approval of the Organic Law of Protective Measures of Integral Protection Against Gender Violence in 2004 (Jefatura de Estado. Governo de España, 2004). This legal apparatus establishes measures to raise awareness, prevent, detect and assist violence against women.

There is a diversity in the characteristics of the professional group allocated to this type of service and their services are offered in different contexts: telephone lines, emergency centers, shelters, associations in administrative, judicial, police scopes, among others (Gomà-Rodríguez, Cantera, & Silva, 2018). During contact with this demand, the offer of listening to the cases of violence against women by professionals refers to the construction of a space both for collecting information and measuring the risks involved in the situation, such as for reflecting on emotions and feelings of confusion in violent relationships and understanding and acceptance of the reality narrated by the battered woman (Gimena, Alonso, & Monzó, 2012).

This professional experience of receiving violence cases can cause feelings of helplessness, anger, frustration and confusion in providers of this type of service (Howlett & Collins, 2014; Penso et al, 2010; Vieira & Hasse, 2017). It is known that there is a biological basis for understanding this phenomenon through mirror neurons in which the brain activates and reflects the interlocutor’s emotion modifying it in an own internal experience (Oliver, Albornoz, & López, 2011).

Thus, as a cost to the health of these professionals, the activity of taking care of treated cases can lead to burnout and secondary traumatic stress disorder. Burnout is a syndrome studied by Freudenberger in the 1970s and developed by researchers Malasch and Jackson that is characterized by the presence of the following components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduction of personal fulfillment (Oliveira, 2015).

Secondary traumatic stress disorder has the following main symptoms: physiological hyperactivation, avoidance of situations similar to those seen in the workplace, and recall of treated cases (Moreno-Jiménez, Morante, Garrosa, & Rodríguez, 2004).

In addition to the need to address these individual psychosocial risks, the team is also a component that reflects the level of illness or burnout present in that work context. This is evidenced by the traumatization of teams that will be present, somehow, in the following aspects: lack of trust among team members, fear of addressing conflicts, lack of commitment from the professional body, avoidance of responsibilities, noise and distortions in communication, tendency towards group disintegration and disarticulation of joint work (Chile, 2009).

These findings are reinforced by harassment practices found in care teams for women victims of violence, as attested by a study by Quiñones, Cantera and Ocampo (2013). Thus, for the healthy progress and development of activities by teams and their members, it is essential that they change the way they perceive work and life and direct their attention to mental, emotional, social and spiritual health. The guiding axis for this change is self-care (Medrano, 2014).

This is an element characterized by the set of care that the person can provide to him/herself to achieve a better quality of life and it can be exercised individually or collectively through groups, family or community (Correa, 2015).

The exercise of self-care, on an individual level, is implemented by actions such as: having room for distraction, knowing how to ask for help, learning to delegate responsibilities, developing emptying and decompression rituals, taking care of food and sleep, incorporating physical activities and care for one's body-mind balance, take responsibility for one's own health and well-being, develop and maintain clear boundaries between work and private life, and create opportunities for maintaining support networks such as friends and family, avoiding isolation (Coles, Dartnall, & Astbury, 2013; Gimena, Alonso, & Monzó, 2012).

This professional caring also reveals itself as an institutional responsibility, since individual or group illness results in damages to the quality of services offered to users, either due to these internal conflicts or the results caused by them (Ginés & Barbosa, 2010). Thus, maximizing the well-being of teams and their members develops through the implementation of strategies such as providing a balance between work and private life, organizing supervisory spaces, developing a culture of learning, sharing and support within the workplace, support in identifying symptoms of secondary traumatic stress and predicting professional development and training (Veslázquez, Rivera, & Custodio, 2015).

In addition to these issues, the protection and attention to basic infrastructure conditions by institutions are also designed as a form of self-care. Among them, the following aspects make up the fulfillment of infrastructural requirements such as: adequate and available spaces for the performance of individual and group activities, sufficient supply of material resources for recording, documentation and professional use with attended cases, good conditions of convenience, privacy, noise regulation and restriction of free movement of persons within the workspaces and adequate transport availability (Chile, 2009).

The positive impact of these self-care practices is demonstrated by studies such as the study carried out by Choi (2011) with social workers in the United States. This study indicated that workers with greater support from their superiors, colleagues, and team, as well as access to strategic organizational information had lower levels of secondary traumatic stress.

Given the considerations and notes on health risks of professionals dealing with human suffering, this study presents the following objectives: describe the working conditions, investigate the experience of care for women victims of violence and observe self-care practices exercised by the professional group at the personal, professional, collective and institutional levels in Spanish service centers.

Method

The sample in the Spanish context consisted of 10 professionals of direct assistance to victims of violence against women. These participants have an average age of 47 years and provide services of this nature in different service centers of public and private associations in Spain.

This is a convenience sampling whose selection criteria followed the parameters of personal availability to participate in the research.

The instrument used was the interview script whose guiding thematic axes of questions were the work trajectory, statements about violence, violence and work, health and daily life at work with violence. The approach with participants of this project in this country was interceded by representatives of four centers to respond to demands of violence against women in order to map the number of professionals specialized in providing services of this nature and available to participate in this study. After this stage, a date and place were scheduled with professionals assisting victims of violence against women to conduct the interviews.

This study followed the ethical recommendations promoted by Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (UAB) through the Ethics Committee on Animal and Human Experimentation (CEEAH).

The collected data were translated and adapted to Portuguese and results were obtained using the computerized program Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (IRAMUTEQ). It is a computerized method that provides different forms of textual analysis resulting in a clear and understandable organization of the collected written material. For this research, the Descending Hierarchical Classification (CHD) was chosen, which provides the vocabulary in classes in a dendogram that clarifies the relationships between them (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

Results and Discussion

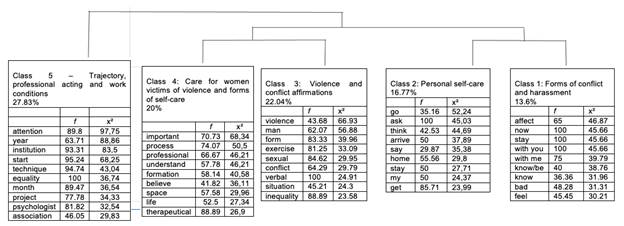

The corpus investigated consisted of 10 UCI (interviews) and was organized into 1,304 text segments and 5,188 words with a frequency of 15.29 words per answer. The elaborated dendogram, based on the homogeneity of text segments (Figure 1), recognized five classes of text segments. Through the analysis of the profiles tab generated by the descending hierarchical classification, the lexical contents of each of these classes are pointed out (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

The most recurring words in each class are described in the dendogram shown in Figure 1. The first 10 words displayed in each class were chosen. Participants' speeches or text segments explained in this analysis were extracted from the Profiles tab so that the context of each class was explained by textual segments characteristic of the researched reality.

At first, the corpus was divided (1st partition) into two subcorpora. On one side, class 5, and on the other, classes 4, 3, 2 and 1. In the next step, the second subcorpus was divided into two (2nd partition), bringing class 4 and 3 on one side and on the other, classes 2 and 1.

Results and discussion of this study will be premiered by Class 5 entitled “Trajectory, professional acting and working conditions” that directs the discussion to practice, the professional path taken by these workers and the working circumstances in which they are inserted. In a second phase, Class 4, entitled “Care for women victims of violence and forms of self-care”, will be discussed, followed by Class 3, “Violence and Conflict Affirmations”. In the development of this construction, the attention of this topic will be directed to Class 2 that received the denomination of “Personal Self-Care” and finally, Class 1, designated “Forms of Conflict and Harassment”, which will finish the discussion about the reality of these professionals in the Spanish context.

Figure 1: Dendogram of the Descending Hierarchical Classification of Corpus “Work of Professionals Assisting Victims of Violence Against Women in Spain”

Professional Performance in Assistance to Women Victims of Violence

Class 5 called “Trajectory, professional acting and working conditions” makes up 27.8% of text segments worked by the corpus. This category is concerned with presenting characteristics of the work path designed by these workers, the ways in which these professionals work with targets of this violence and the work environment in which they are allocated.

The professional course of these interviewees is characterized by changes in the professional role so that, at a given moment, they enter the care services for women victims of violence. This statement can be elucidated by the following clipping: “Before finishing my degree, I worked in the city hall as a socio-cultural animator, but my work as a professional, besides being a volunteer in the whole issue of therapy, was as a prison educator. I was young and then in the women's prison in Barcelona for ten years. So I came here (...).” (Participant 9).

Within this professional path taken by these professionals, it is identified that the entrance of these workers in the context of care for women targets of violence is undertaken by the construction and/or implementation of projects in institutions that host this public. Besides being a way of access to this labor field, projects are the main axis of action of these professionals in the fight against violence against women.

In speeches of the interviewees, references are found to this type of intervention that unfolds in different ways, denominations and objectives: “We have a dedicated individual psychological counseling area, specialized criminal, civil and family legal counseling, we have a group of volunteers trained in a pioneering project called “Veines per veines” (neighbors by neighbors)." (Participant 9)

As described so far, it is clear that the entry of these women in this area of activity and the concomitant change in their work trajectory is accomplished by the implementation of care projects for battered women. However, it should be noted that the diversity of professional spaces occupied by these professionals, along their professional trajectories, point to their functional flexibility.

This versatility of occupations is matched by the idea of qualitative flexibility, as pointed out by Hirata (2007), which is characterized by its versatility and its ability to inserting into a productive organization based on a variety. This finding is part of a reality of a capitalist society that needs, in its accumulation process, a flexible and cheap availability of the female labor force (Nascimento, 2014).

In addition to being exposed to this delineation in the work market, the interviewees' statements refer to working conditions in care centers for women victims of violence characterized by weakened contractual links, work overload, low pay, lack of structure and long hours of labor. This note is revealed by the following discourse:

Well, I think I suffered more like the institution or the place or the work or the structure. They don't recognize you, they don't pay you enough, or they don't give you the emotional support we would need, I suffered too much from it. (Participant 10)

As pointed out below by participant 6, excessive workload impacts the quality of care given to cases of violence:

I am working there and maybe I see a woman who is undecided, or who is in a riskier situation (...), but because of the schedule availability, I can't pay a visit until a month and a half from now.

The use of functional flexibility and subjection to forms of labor with precarious labor guarantees found in the female professional reality are also supported by socio-cultural legitimation. This translates into subordination to labor activities in more precarious circumstances mirroring the sexual division of labor that attributes the public space to men and women, the private domestic environments (Nascimento, 2014).

In addition to being subject to a logic of precarious work, these professionals are in contact with a reality characterized by the denial or social concealment of violence whose revelation impacts on the physical and mental health of witnesses of aggression stories. This picture will be portrayed by class 4 entitled “Care for women victims of violence and forms of self-care."

The following statement exposes the portrait of the situation of professionals facing cases of violence attended: “But, besides, we are very much left in the “hands of God”, at the social level, there has been a very important change, the people who work with violence are very much exposed continuously, more and more families, more and more situations.” (Participant 5).

In addition to the weariness of witnessing the target's imprisonment in the cycle of violence, these professionals need to face the risk of being targeted by some kind of violence. As pointed out by Ojeda (2006), these two aspects compose sources of illness of external origin. This reality is reinforced by reports of signs of physical and emotional illness that once again signal the emotional mobilization involved in this activity: “There are so many emotions and I started going to a chiropractor who works everything in a holistic way, not only physically. Understanding that the physical is emotions that are blocked, and then I did therapy, gym or something else.” (Participant 8).

As a consequence of the emotional distress caused by recurring approaches to these stories, some respondents also reported the appearance of burnout syndrome within this professional context. This finding brings us to costs associated with the care of cases that can lead to burnout, fatigue due to empathy or vicarious trauma and secondary stress disorder (Oliveira, 2015).

Thus, to preserve health and avoid the risk of illness in the face of this reality, self-care is an element of health promotion and quality of life for workers and can be exercised individually or collectively through groups, families or community (Correa, 2015). The speeches below mention the forms of self-care mobilized by the surveyed professionals: “(...) understanding that when you are working with violence, self-care is a very important part and doing what you can that does you good.” (Participant 1), “(...) that there is this part of trying to take care of yourself, trying to do as much as possible and therefore establishing some spaces, more or less basic, for me therapy is sacred.” (Participant 6).

According to the above notes, interviewees are aware of the risks involved in this service and, therefore, seek individual actions to preserve health and distance from diseases. One of the actions signaled is participation in an individual psychotherapeutic process, which, as described by participant 6, has become a resource for coping with this reality and reducing physical symptoms.

On the other hand, despite their attempts to care for themselves individually, these respondents are exposed to few actions of this nature at the institutional level or even their absence: “(...) at the institutional level, I think it is for lack of motivation and interest because we don't have the means to take care of the team. Look, we, in our case, the good thing they have is that they allow us to do a lot of training." (Participant 5). "I can't be fine because I spend my salary on therapies. Here the institution would have to do things to prevent psychosocial risks.” (Participant 8).

The institution's role in promoting self-care for its workers is a point of significant impact on team health (Kulkarni, Bell, Hartman, & Herman- Smith, 2013). However, what can be seen from the transcribed reports is that the institution does not adopt this type of role or does it insufficiently. Some entities offer professional training or supervision of cases treated and others do not pay attention to these actions, which mobilizes the financial resources of workers in the search for prevention of psychosocial risks.

Besides the consequences suffered in detriment of the approximation with the history of violence of attended cases, these professionals are also situated in a social and institutional scenario permeated by conflicts and violent interactions. Understanding of this conjuncture will be made explicit by class 3 called “Violence and Conflict Affirmations”.

Conflict, Self-Care and Harassment in Care of Women Victims of Violence

This class, accounting for 22.04% of text segments, reveals the statements made by participants about conflicts and violence. Within this construction, these researches point to socio-cultural issues that catalyze gender-based violence, narrate the emergence of violent acts and their circumstances, and, finally, trace evidence of conflicts within the workplace and the institution as a missing element in conflict resolution.

Regarding gender violence, the respondents indicate how education makes stereotyped gender markings that trigger the confinement of men and women in fixed and defined roles whose consequences are present in the naturalization of male aggressiveness and concomitant male violence as well as the vulnerability of women in the face of economic and sociocultural appeals: “Male chauvinistic violence is against women because they are women, but we see that this education has caused men to practice violence against women, but also against other men.” (Participant 10); “(...) the market tries to make us all inadequate. That's why we buy, spend, look for impossible desires, but in the case of women, it's even more blatant, so you have every basis to legitimately engage in all this violence.” (Participant 6)

These considerations resonate with the writings of Bourdieu (2016) that point to constitutive divisions of the social order, promoted by family, social, institutional and cultural environments, as the basis for classifying and distinguishing things from the world and all practices in separate spaces reducible and opposites between male and female. In this order, women are relegated to resignation and submission through this work of socialization in an androcentric context.

Within these statements, it is questioned how female professionals immersed in an aggressive and male chauvinist scenario visualize the acts of violence witnessed in the care of battered women. To problematize this point, it is discussed below speech taken from this research that point to the description of violence phenomenon as something characterized by invisibility, subtlety, variety of forms and unconsciousness of acts: “In all relational contexts, sometimes violence does not have a reason, most of the time it is not always exercised physically or tangibly, there can be symbolic violence, violence of several kinds, in any field.” (Participant 4).

The recognition of forms of violence assisted in service provision is consistent with Hirigoyen's (2006) notes on the different forms of violence in love relationships and, especially, the psychological violence that is characterized by the adoption of behaviors, expressions and attitudes aimed at denying the other's way of being. Within this characterization, subtlety and invisibility are also found in the author's exercise of violent acts.

On the other hand, when elaborating the recognition of characteristics of attended aggressions, it is identified a confluence in experiences of conflict and violence experienced by professionals in their work environments with the public served. As reported in the following speeches, the boundaries between conflicting situations and episodes of violence in these spaces adopt sometimes faint, inaccurate or unnamed features, sometimes the respondents occupy a position of spectators or relievers of conflicts: “Well, I have found some people who do not listen and want their decision to be agreed. It is a form of conflict, not letting you talk, talking to you abruptly, creating a situation abruptly.” (Participant 8).

(...)situations with someone who has a very strong character and so, oh well, I'm cold, I'm hot. And you adjust the air conditioning because you are cold and someone comes and suddenly someone changes the temperature of the device to impose their will. (Participant 9)

This invisibility and naturalization of conflicts and violent events are aspects found, in part, by the research promoted by Quiñones, Cantera and Ocampo (2013) with professionals who work in places of assistance to violence that, among other points, point to consequences physical and mental health caused by exposure to these experiences of violence.

Following this discussion, the institutional figure presents itself as an axis that dynamizes the mental illness and removal of workers due to rigid hierarchical structures and the lack of attention and preparation to deal with the psychosocial risks involved in the care of women victims of violence: “(...), but where I lived most of the violence was at the institutional level. Because the institution is not prepared to give you answers.” (Participant 4).

(...)Again, I left because the person who had been my tutor was not mentally well. For my health, I had to go. The institution did nothing to stop this person from being there, and for my health and for me, I had to leave. (Participant 1)

These data reinforce the findings found in class 4 regarding the absence and insufficiency of self-care promoted by the institution and indicates, once again, how this agent plays an important role in team health (Kulkarni et al, 2013). In addition, as reported above, this agent does not handle emerging team conflicts, maintains distance in the education of its employees to detect signs of traumatic stress or burnout, as well as creates conditions for an illness and emergency/conflict-strengthening workplace and violence in work relations.

On the other hand, faced with this context permeated by conflicts and violence in the provision of services or in social spaces at work, these respondents create personal resources as the basis of empowerment to manage this context. The detail of this scenario will be in Class 2.

This class called “Personal Self-Care”, composed of 22.04% of text segments, discusses the personal and social resources triggered by participants to preserve their health when dealing with events of conflict and violence, and in the care of the targets of violence, whether in the relationships undertaken in their workspaces.

The first aspect revealed is about the performance of physical activities by the respondents as a clearer way of understanding the problems experienced, strengthening and maintaining the mood or even appreciation of the exercise itself. The following extract characterizes this issue:

(...)I go running, I walk and I realize that thinking of movement changes me, works and gives me clarity. Because before I could maybe stay at home or on the couch, in bed and such and I realized that when I have a problem and walk, it facilitates clarification of ideas. (Participant 4)

The incorporation of physical activities and care with the body-mind balance are configured as personal self-care paths (Veslázquez, Rivera, & Custodio, 2015). The entry of this way of taking care of yourself, as said above, assumes that the practice of physical exercise adds benefits to the body and mind of these participants.

This approach and recognition of the internal reality in the face of contact with the external world and vice versa also become tools for managing events arising from the provision of services to the public served and in relations with other actors in the working context: “(...) I was doing something I wasn't trained for and it scared me. With therapy, I grew stronger, knowing what my limits were, what I could do, and what I couldn't do.” (Participant 4).

This principle of identifying and discerning their subjective experiences becomes a fundamental axis of empowerment and care for themselves, as well as a way to elaborate your actions and understandings in face of this reality. Within this recognition of their psychological particularities, this professional group carries out their interventions, responses and conceptions about the episodes experienced in the provision of services and interaction with colleagues in a more active, assertive and safe manner: “(...) well, In a meeting, I had to get up and cry because I thought why the hell I have to put up with it. And now that I see with more, with more distance and so” (Participant 4). “I face, I face, I have a strong character, although I am very sensitive, I am a very assertive girl (...)” (Participant 8).

This way of setting boundaries and addressing these events transcribed above is designed as a result of this investment in their internal reality as well as a self-care exercise (Ginés & Barbosa, 2010) in delimiting, externalizing, facing and resignifying the demands and unfolding in contact with the individual public and professional network.

Despite the predominance of self-care exercise in a more independent and self-centered field, speeches were also directed to the importance of family relationships and the network of friends. These findings are presented in the lines below: “(...) Well, I like to read, I like to write, I like to go to the movies and comment on movies, I like to have dinner, go out to dinner, talk, meet friends, friends.“ (Participant 8).

My husband and I have a relationship. My husband and I have been very close friends for two years and we fell in love and I think it is a foundation that has remained in the relationship and so actually this is very good for me. (Participant 3).

As explained above, the family environment and friends' network are sources of security and support for these professionals, emerging as social support of great importance. According to Campos (2016), social support is understood as the source of interpersonal relationships that provides feelings of protection and support, generating a sense of being recognized, cared for and accepted, as well as a basis that generates conditions for coping with everyday stress to the recipient.

Thus, it appears from this class that the practices of self-care at the individual level are located in actions of identification and recognition of their subjectivities, autonomy and self-empowerment so that they are used with assertiveness and safety through the demands of their work context in contact with the public served, either in labor relations. At this level of discussion, it is worth pointing out how culture influences the determination of personal skills and attitudes for health preservation, disease prevention and the achievement of a better quality of life (Correa, 2015).

Returning to the questions raised about claims of conflict and violence, it is identified in Class 1 called “Forms of Conflict and Harassment”, accounting for 13.6% of text segments, that the invisibility, inaccuracy and subtlety of conflicting and violent situations found in Class 3 acquire a more objective and clear definition.

Regarding harassment practices, speeches are identified that refer to the experience of isolation and refusal of communication that are perceived by the targets as a subtle practice: “(...) because a year ago, I had an affectation, of which I was not aware, but I found that I was working alone, not as a team.” (Participant 9).

(...)Here I think there was an exercise of violence by the other. On the way of talking. The way to transfer information, in a very subtle way, with things like your birthday. I know it is and everyone congratulates you and one person doesn't congratulate me. (Participant 4)

In the speeches noted above, it is observed that this practice materializes through gestures, words and behaviors systematically and repeatedly within the field of relations in workspaces. Both isolation and refusal of communication convey the wordless message that the other does not interest or even does not exist for the perpetrator of violence (Hirigoyen, 2006). These violent actions cause target affects such as renunciation, confusion and fear.

These harassing and conflicting situations emerged in the management of multiple activities bringing the precariousness aspect of the work assigned in Class 5 and the sharing of decisions for the progress of activities. The following statement elucidates this statement: “(...) we managed everything, we managed, from the entrance of the door, printer, the schedules. Everything. The calls, I mean the entire overload, all the overload that were the management, all this generates discomfort and can generate conflicts in a team, yes.” (Participant 7).

Entering these situations of harassment and conflict, one identifies the appearance of characteristics present in labor relations that are marked by individualistic, precarious, overloaded and lack of recognition of the other. It is walking in a space that recalls how workers are subjected to any employment condition and are subject to new management based on high performance to shake off the threat of unemployment (Barreto & Heloani, 2015; Figueredo, 2012).

Occurrences of harassment and conflict are practiced in an upward and downward direction as punctuated by the following statement: “(...) there were actions or ways the bosses treated me that I did not like. It is true. We can talk about authoritarian people that if you don't agree with them, they will isolate you.” (Participant 1).

Downwardly abusive behaviors are characteristic of highly hierarchical structures (Freitas, Heloani, & Barreto, 2008) and is the most common form of violence relief (Quiñones, Cantera, & Ocampo, 2013). On the other hand, the statements above show that participants experienced this violence when they occupied management positions or committed violent acts directed at these spaces.

In this context of living with conflicts and harassment, it is clear that the lack of involvement of institutional agents in the management and resolution of conflicts and violent practices bring psychological consequences to targets such as insecurity and anger:

(...)And of course, it affects, if you with your colleague or your colleague, you have to do regular interviews, you have to do home visits, you have to accompany families somewhere, and it turns out that he is angry with you. (Participant 9).

The situation portrayed is constructed with the notes of Sansbury, Graves and Scott (2015) that points to the need for institutions to handle conflicts within their own team without achieving the quality of services provided. In addition, they reinforce how these professionals are immersed in fragile employment relationships that impact not only employees, but also others who establish professional ties and recognition of the quality of services provided.

The exposition of findings of this class indicates that conflicts and practices of violence in the workplace are intertwined in the speeches of those surveyed by other aspects related to working conditions that, as discussed in Class 5, are characterized by precariousness whose presence in work environments provides the emergence of violence in these scenarios (Pioner, 2012).

Given the findings listed in this debate, it is directed, at this moment, to an understanding that these Spanish professionals are subject to a series of factors that potentiate the risks of illness in addition to that already afforded by the very nature of work.

In contrast, these workers are aware of the risks involved in the practice of their activities and thus assume the position of investing in their self-care on a personal level, either by investing in their autonomy and recognizing their psychic world, which in some cases have been promoted psychotherapy, either by approaching the networks of family and friends.

Conclusion

This research indicated, through the exploration of interviews, evidence of precarious working conditions, stories of illness in this work context, professional trajectories marked by functional flexibility, statements about violence and conflicts prepared by participants about the witnessed cases that refer to their own experiences of this nature in their workspaces and their individual efforts to take care of their own health given their understanding of risks involved in the activity.

In this researched environment, workers made considerations about conflict and violence that point to the invisibility, variety of forms, subtlety and naturalization of these phenomena in attended cases. However, these statements are intertwined by the conflicting and aggressive experiences they experienced in relationships within the workplace. In conjunction with this situation, reports are also found about not only precarious institutional self-care, but also the appearance of these agents as factors of potential damage to the health of these employees. This reality brings us to the notes of Kulkarni et al (2013) about the considerable influence that institutions have on the health of professionals.

In contrast, respondents promote an individual work of approaching, recognizing and empowering their internal world, either through the practice of physical activities or psychotherapy, as ways of more assertive and safe management of demands arising from attended cases and in contact with the professional network. This pursuit of investment itself is designed as personal self-care (Coles, Dartnall, & Astbury, 2013; Gimena, Alonso, & Monzó, 2012) as insight and identification of one's own subjective experiences drive the construction of boundaries, empowerment autonomy and safety in interventions with the outside world. It is worth noting that the construction of these self-care skills is interspersed with cultural issues (Correa, 2015).

This exploration also pointed to the need for institutional agents to adopt practices aimed at addressing conflicts and reinforcing personal self-care practices, health care for professionals through education and monitoring of signs of vicarious trauma, traumatic stress burnout and signs of harassment in the team (Sansbury, Graves, & Scott, 2015). Given the precarious working conditions, the forms of illness found and the scarce or nonexistent institutional efforts to take care of the workers' health, we highlight the importance of the full and homogeneous implementation of current self-care programs, the discussion of the role of women's condition in the labor market and the elaboration of proposals to take care of the professional team that take into account the social, economic and cultural particularities of the places of intervention.

When thinking about the role played by institutions, it is essential to remember that they are immersed in a neoliberal capitalist logic that increasingly strives for the weakening of working conditions, the cheap use of female labor force and the charging of high performance in performing functions (Nascimento, 2014). Thus, the effective implementation of self-care practices goes beyond the institutional spheres.

Finally, the present research has limitations that may be overcome by future studies. The first refers to the lack of application of an instrument that measures and verifies burnout reports so that these findings were related to other aspects of this research. The second issue is characterized by the absence of investigative questions about aspects involved in elements inherent to organizational dynamics. The third limitation lies in the lack of questions that understand the circumstances that lead to unmanaged conflict as a potential source of workplace bullying.

REFERENCES

Barreto, M., & Heloani, R. (2015) Violência, saúde e trabalho: a intolerância e o assédio moral nas relações laborais. Serviço Social e Sociedade, 123, 544-561. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-6628.036 [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (2016). A dominação masculina: a condição feminina e a violência simbólica. Rio de Janeiro: Bestbolso. [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., & Justo, A. M. (2013). Tutorial para uso do software de análise textual IRAMUTEQ. Florianopolis-SC: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Disponível em http://www.iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/tutoriel-en-portugais [ Links ]

Campos, Eugênio Paes (2016). Quem cuida do cuidador? Uma proposta para profissionais de saúde.2a ed. Teresópolis: Unifeso; São Paulo: Pontocom. [ Links ]

Chile (2009). Manual de orientación para la reflexividad y el autocuidado Dirigido a Coordinadores de Equipos Psicosociales de los Programas del Sistema de Protección Social Chile Solidario. Santiago de Chile: Mideplan. [ Links ]

Choi, G. Y. (2011). Organizational impacts on the secondary traumatic stress of social workers assisting family violence or sexual assault survivors. Administration in Social Work, 35(3), 225-242. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03643107.2011.575333 [ Links ]

Correa, O. T. (2015). El Autocuidado Una Habilidad para Vivir. Hacia la promocion de la salud, 8(1), 38-50. Disponível em https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/33538149/EL_AUTOCUIDADO.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1523484916&Signature=YW07G7pVFvMVQjkwFaQp3yg2F%2BU%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DEl_AUTOCUIDADO.pdf [ Links ]

Coles, J., Dartnall, E., & Astbury, J. (2013). “Preventing the pain” when working with family and sexual violence in primary care. International journal of family medicine. 1-5. Disponível em http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/198578 [ Links ]

Freitas, M. E. de Heloani, R., & Barreto, M. (2008). Assédio moral no trabalho. São Paulo, SP: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Figueredo, P. M. (2012). Assédio contra mulheres nas organizações. São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Gimena, M. M.R., Alonso, E.P., Monzó, L.M. (2012). Guía didáctica de formación de formadoras y formadores para la atención a la violencia de pareja hacia las Mujeres. Agência Laín Entrago. Consejería de Sanidad: Comunidad de Madrid. Recuperado de http://www.madrid.org/cs/Satellite?c=CM_Publicaciones_FA&cid=1142695400469&language=es&pagename=ComunidadMadrid%2FEstructura [ Links ]

Ginés, O., & Barbosa, E. C. (2010). Cuidados con el equipo cuidador Cuidados com a equipe de atendimento. Revista Brasileira de Psicoterapia, 12(2-3), 297-313.Disponível em http://www.conexus.cat/admin/files/documents/14_CuidadosEquipoProfesionalViolenciaTrauma_OriolGines.pdf [ Links ]

Gomà-Rodríguez, I., Cantera, L. M., & Silva, J. P. da (2018). Autocuidado de los profesionales que trabajan en la erradicacion de la violencia de pareja. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 17(1). Recuperado de http://www.psicoperspectivas.cl/index.php/psicoperspectivas/article/view/1058/740 [ Links ]

Hirigoyen, M. F. (2006). A violência no casal: da coação psicológica à agressão física. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Bertrand Brasil. [ Links ]

Hirata, H. (2007). Flexibilidade, trabalho e gênero. In: H. Hirata & L. Segnini (Orgs.) Organização, Trabalho e Gênero (89-108). São Paulo: Editora Senac São Paulo. [ Links ]

Howlett, S. L., & Collins, A. (2014). Vicarious traumatisation: risk and resilience among crisis support volunteers in a community organisation. South African Journal of Psychology, 44(2), 180-190. Disponível em http://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC153403 [ Links ]

Kulkarni, S.; Bell, H.; Hartman, J. L. & Herman-Smith, Robert L. (2013). Exploring individual and organizational factors contributing to compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout in domestic violence service providers. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 4(2), 114-130 https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.5243/jsswr.2013.8 [ Links ]

Medrano, S. G. (2014). Promoción del autocuidado desde el cuerpo: La importancia del cuerpo en el autocuidado en equipos profesionales. México, D. F.: Equidad de Género: Ciudadanía, Trabajo y Familia, A.C. http://repositorio.gire.org.mx/handle/123456789/2722 [ Links ]

Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Morante, M. E.; Garrosa, E., & Rodríguez, R. (2004). Estrés traumático secundario: el coste de cuidar el trauma. Psicología conductual, 12(2), 215-231. http://www.uam.es/gruposinv/esalud/Articulos/Salud%20Laboral/2004el-coste-cuidar-el-traumapsconductual.pdf [ Links ]

Nascimento, S. D. (2014). Precarização do trabalho feminino: a realidade das mulheres no mundo do trabalho. Temporalis, 14(28), 39-56. https://doi.org/10.22422/2238-1856.2014v14n28p39-56 [ Links ]

Ojeda, T. E. (2006). El autocuidado de los profesionales de la salud que atienden a víctimas de violencia sexual. Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia, 1(52), 21-27. Disponível em http://sisbib.unmsm.edu.pe/BVRevistas/ginecologia/vol52_n1/pdf/a05v52n1.pdf [ Links ]

Oliveira, R.M. K. de. (2015). Pra não perder a alma: o cuidado aos cuidadores. 3ª ed. São Leopoldo: Sinodal. [ Links ]

Oliver, E. B., de Albornoz, P. A. C., & López, H. C. (2011). Herramientas para el autocuidado del profesional que atiende a personas que sufren. FMC-Formación Médica Continuada en Atención Primaria, 18(2), 59-65. Disponível em https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/42878634/Herramientas_para_el_autocuidado_del_pro20160220-23006-1oemzes.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId= AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1523476912&Signature=Uy%2Bv3iRVrocAeJQZmrBNps%2B642E%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DHerramientas _para_el_autocuidado_del_pro.pdf [ Links ]

Penso, M. A., Almeida, T. M. C. de, Brasil, K. C. T., Barros, C. A. de, & Brandão, P. L. (2010). O atendimento a vítimas de violência e seus impactos na vida de profissionais da saúde. Temas em Psicologia, 18(1),137-152. Recuperado dehttp:// pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413389X2010000100012 [ Links ]

Pioner, L. (2012). Trabalho precário e assédio moral entre trabalhadores da Estratégia de Saúde da Família. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Trabalho, 10(1),113-120. Recuperado de https://www.cmfc.org.br/sul/article/view/16. [ Links ]

Quiñones, P., Cantera, L. M., & Ocampo, C. L.O. (2013). La violência relacional em contextos laborales que trabajan contra la violência. In L.M. Cantera, S. Pallarés & C. Selva (Eds.), Del Mal-estar al Bienestar Laboral (135-155).Barcelona: Amentia Editorial. [ Links ]

Sansbury, B. S.; Graves, K. & Scott, W. (2015).Managing traumatic stress responses among clinicians: Individual and organizational tools for self-care. Trauma, 17(2), 114-122 Disponível em http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1460408614551978 [ Links ]

Veslázquez, T., Rivera, M., & Custodio, E. (2015). El acompañamiento y el cuidado de los equipos en la Psicología Comunitaria: Un modelo teórico y práctico. Psicología, Conocimiento y Sociedad, 5(2), 307-334. [ Links ]

Vieira, E. M., & Hasse, M. (2017). Percepções dos profissionais de uma rede intersetorial sobre o atendimento a mulheres em situação de violência. Interface-Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, 21(60), 52-62. Disponível em DOI: 10.1590/1807-57622015.035 [ Links ]

Note:Authors' participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. K.D.A.S contribuiu em c, d; J. P. S em a, e; A.P. T em a, b; L.M.C.E em a, e.

Correspondence: Karine David Andrade Santos, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, São Cristóvão, SE, Brasil, Av. Marechal Rondon, s/n. Rosa Elze São Cristóvão/SE CEP: 49100-000, Brasil. Email: e-mail: psimulti@gmail.com. Joilson Pereira Silva, joilsonp@hotmail.com. Alícia Perez Tarrés, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona: Bellaterra-Barcelona, Barcelona, Espanha, Edifici B Despatx B5/040, Campus de la UAB · 08193 Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès). Email: ptt.alicia@gmail.com. Leonor María Cantera Espinosa. Email: leonor.cantera@uab.cat

Received: June 14, 2018; Accepted: May 16, 2019

texto en

texto en