Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.13 no.1 Montevideo jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i1.1814

Original Articles

Evaluation of the prejudice towards immigrants: Argentine adaptation of the scale of subtle and blatant prejudice

1 Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Argentina luciana.civalero@hotmail.com, alonsodaniela@conicet.gov.ar, sbrussino@conicet.gov.ar

4 2 CONICET. Argentina Correspondence: Luciana Civalero. CONICET y UNC. Facultad de Psicología, Enfermera Gordillo esq. Enrique Barros. Ciudad Universitaria -5000- Córdoba, Argentina. Email: luciana.civalero@hotmail.com. Daniela Alonso, email: alonsodaniela@conicet.gov.ar. Silvina Brussino, email: sbrussino@conicet.gov.ar

Abstract: The aim of this article is to analyze the psychometric properties of the scale of Blatant and Subtle Prejudice, developed originally by Pettigrew and Meertens (1995), in the Argentine context. This scale has five dimensions: two that evaluate blatant aspects and three that measure subtle aspects of prejudice. We took self-selected non-probabilistic sample of 856 tertiary and university students from the cities of Córdoba (N= 253), Buenos Aires (N= 193), Salta (N= 200) and Neuquén (N= 210). A confirmatory analysis was performed in order to access the scale structure and the Cronbach's Alpha coefficient was estimated to evaluate internal consistency. We also performed a convergent test through a correlation analysis between our scale and two variables whose correlation to prejudice was previously proven. The results supported the five dimensions structure proposed by the original authors, with 18 items and satisfactory internal consistency and validity indicators. In addition, favorable evidence of convergent validity was obtained.

Key words: subtle prejudice; blatant prejudice; discrimination; ethnic prejudice; immigrants

Palabras clave: prejuicio sutil; prejuicio manifiesto; discriminación; prejuicio étnico; inmigrantes

Introduction

Integration between culturally diverse groups is one of the greatest challenges of modern societies. While governments and educational systems worldwide have developed social strategies to mitigate these antagonisms, none has proven to be successful in all situations. Licata et al. (2011) claim that prejudice is rooted in a form of interaction where a majority group does not recognize another minority group as deserving of social esteem, that is, as worthy of access to the public sphere. Thus, although the formal rights of foreign citizens are being progressively recognized, as long as negative emotions and stereotypes continue replicating, their integration in societies will remain a distant ideal.

In this sense, according to Rueda and Navas (1996), in a contemporary social climate where the majorities value democratic and egalitarian ideals, there is a social rejection towards open discriminatory behavior, based on race, religion or ethnicity. On the other hand, there are implicit forms of discrimination against certain type of social groups, which would be accepted by the social environment. Thus, it is common to subtly discriminate against certain groups based on cultural differences, economic competence (for example, when they are seen as competitors for labor supply) or the fact that they benefit from state resources. In certain social circumstances, this expression can turn into blatant racist manifestations (Rueda & Navas, 1996).

As an example, research has found a relationship between the unfavorable perception of the economic situation and the prejudice towards immigrants (Cosby, Aanstoos, Matta, Porter & James, 2013; Fischer, Hanke & Sibley, 2012; Kessler & Freeman, 2005; Sánchez, 2014). Furthermore, Domenech and Magliano (2008) explain that in periods of economic crisis, immigrant groups tend to be considered as "unacceptable" and tend to be blamed for the social ills of the time. In Argentina, especially in these critical circumstances, mass media -socially defined as conservatives- have spread discourses aimed to promote xenophobic expressions against certain minorities coming from other countries (Pizarro, 2012; Sar, 2016; Valverde, 2015).

Thus, ethnic prejudice uses particular traits of minorities, connoting them negatively and using them as legitimizing beliefs of discriminatory practices. In addition, different contextual aspects -such as migratory flows that make certain groups of migrants visible, legislative frameworks of regulation and integration / exclusion policies, economic and social crises and hegemonic discourses- contribute to the exacerbation of these manifestations. During the last decades, Argentina has develop less restrictive legal frameworks aimed at the inclusion of immigrant groups with an emphasis on the human rights perspective (INADI, 2016a; López Rita, 2017; Velez & Maluf, 2017). However, equalitarian rights have not been really conquered in the exercise of citizenship (López Rita, 2017). In this sense, true integration would imply the cessation of discriminatory behavior and representations deeply rooted in Argentine society (INADI, 2016b; Muller, Ungaretti & Etchezahar 2017; Sar, 2016). In this framework, the study of ethnic prejudice continues to be a relevant issue.

Traditionally, the empirical study of ethnic prejudice focused on the most blatant forms of the phenomenon, capturing extreme and intolerant expressions of racism based, for example, on the belief in the genetic superiority of the ingroup (Rueda & Navas, 1996). Progressively, the measurement instruments developed in the initial stages of prejudice studies began to show evidence of decreasing levels of prejudice. However, social inequalities and discriminatory practices continued to be recorded (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). This raised the suspicion that the instruments were not adequately accounting for the phenomenon they wanted to evaluate. In this vein, Frey and Gaertner (1986) showed results from numerous studies in different contexts that stated that racism had not decreased. In fact, old forms of ethnic prejudice had turned into more subtle, complex and maybe more insidious forms of intolerance. Therefrom, new theoretical approaches were developed that analyzed these “new” and more indirect forms of rejection in terms of "modern racism" (Campo-Arias, Oviedo, & Herazo, 2014; Chambers, Schlenker & Collisson, 2013; McConahay, Hardee & Batts, 1981), "symbolic racism" (Berg, 2013; Chambers, Schlenker & Collisson, 2013; McConahay & Hough, 1976), "aversive racism" (Dovidio, Gaertner, & Pearson, 2017; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986; Minero & Espinoza, 2016), and "subtle prejudice" (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1992; 1995).

From this framework, Pettigrew and Meertens (1995) pointed out the inability of the existing prejudice measurement to capture these new forms of discrimination. Consequently, they developed a more complex scale that aimed to capture both subtle and blatant prejudice. Thereby, they contribute to bring this distinction from the theoretical level to an empirical one (Coenders, Scheepers, Sniderman & Verberk, 2001) developing a validated measurement that could -at least partially- overcome the influence of factors such as social desirability (Cárdenas et al., 2007; Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). Additionally, that empirical proposal not only differentiates between those two general aspects of prejudice, but also proposes a multidimensional structure within them. On the one hand, they posit two dimensions accounting for blatant prejudice. The first one was named as Threat and Rejection and assess racist beliefs based on the genetic inferiority of the outgroup, used as a justification of the unfavorable position of the latter in society, also denying the existence of discrimination towards these groups. The second component of blatant prejudice is named Intimacy and it refers to an emotional resistance to maintain close relationships with the outgroup. On the other hand, subtle prejudice comprises three dimensions that express prejudice in ways that are considered normative and acceptable in Western societies (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). The first dimension of subtle prejudice entails the defense of traditional values inherent to the ingroup and used them as a parameter from which to determine which behaviors are acceptable and necessary to be successful in the society in question. In contrast, it assumes that members of the outgroup act in improper ways. The second component involves the exaggeration of cultural differences, considering them as the reason of the disadvantaged position of the outgroup. Although these cultural differences may be real, in this case they are exaggerated and become stereotypes. Finally, the third subtle prejudice dimension involves the disguised denial of positive emotional responses to the outgroup. This dimension is understood as the most novel contribution of this proposal because it includes an affective dimension (Rueda & Navas, 1996).

This instrument has been translated and adapted for the Spanish context by Rueda and Navas (1996), being that the first psychometric study for a Spanish version. In turn, it has been applied for other researchers to evaluate prejudice towards ethnic minorities with satisfactory results (Canto, Perles, & San Martín, 2012; Cárdenas et al., 2007, Muñiz, Serrano, Aguilera & Rodriguez, 2013; Rubalcaba & Quintero, 2013; Ramirez Barría, Estrada Goic, & Yzerbyt, 2017). This version of the scale showed a two-dimensional structure and satisfactory reliability coefficients that allow the differentiation between subtle and blatant prejudice. Additionally, both dimensions were positively but moderately related which evidences that they are two distinct expressions of the same phenomenon. Also, Rueda and Navas (1996) warn about the possibility that the evaluation of both dimensions is subject to the effect of social desirability, requiring new attempts of adjustment to the social context.

In Latin America, the adaptation of Cárdenas et al. (2007) to the Chilean context specifically addresses prejudice towards ethnic minorities in the region and presents psychometric evidence that supports its validity. These authors also replicated a two-dimensional structure that reflected the theoretical dimensions of the original construct, being consistent with the previous evidence. They also presented evidence of satisfactory reliability, as well as positive and significant correlations between the two sub-scales.

In the case of Argentina, up to now are not any local psychometric studies on the application of this scale for the analysis of prejudice towards immigrants. However, there is a local version of this instrument which assesses prejudice toward “villeros” (stereotypical representation about people of social disadvantaged groups who lives in “villas”) (Muller et al., 2017). There is also a theoretical review that presents evidence on the development of this instrument in Latin America (Ungaretti, 2017). This previous studies are relevant antecedents for our own research proposal, being relevant to develop specific instruments to assess attitudes toward immigrants.

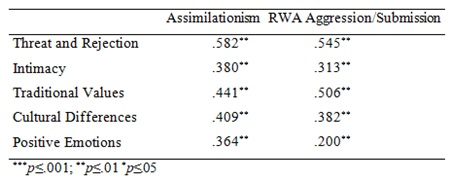

Consequently, our objective is to adapt and test a local version of the Subtle and Blatant Prejudice Scale developed by Pettigrew and Meertens (1995), evaluating its psychometric properties and its validity for the study of prejudice towards immigrants in Argentina. In addition, we assess not only the differences between the subtle and blatant dimensions, but the sub-dimensions within them. We also seek to provide evidence of convergent validity analyzing it’s correlation with Assimilationism and Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA), two variables that the literature has considered to be related to prejudice. This analysis will allow us to account for the adequacy of this instrument to measure the phenomenon we are interested in (Blacker & Endicott, 2002).

Assimilationism is a form of integration in which people recognized as culturally diverse must adapt to the dominant culture which concept is opposed to multiculturalism (Levin et al., 2012). Previous research has shown that those who hold attitudes that imply the desire for immigrants to abandon their customs and cultural values in order to adapt to the dominant ones, tend to show more prejudice and are less willing to demonstrate positive emotions towards them (Berry, 2006; Guimond et al., 2010; Levin et al., 2012). This differentiation in-outgroup, which associate a strong negative connotation to the outgroup characteristics, accounts for a belief in the superiority of the ingroup, a typical expression of prejudice (Bizumic & Duckitt, 2012; Jost & Hunyady, 2003; Monsegur, Espinosa & Beramendi, 2014).

We also analyzed the correlation between anti-immigrant prejudice and RWA. Previous studies posited that, among groups characterized by an orientation towards the preservation of norms, RWA was a strong predictor of negative attitudes towards diverse ethnic groups (Dru, 2007) or towards immigrants (Quinton, Cowan & Watson, 1996). According to some studies, the activation of threat perception could explain this correlation between RWA and Prejudice (Cohrs & Asbrock, 2009; Dru, 2007; Duckitt & Sibley, 2009).

Method

Participants

Our data was obtained from young adults who are studying at University in state or private institutions in four Argentinian cities: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (CABA) and metropolitan area, Córdoba City (Central region), Salta (Northern region) and Neuquén (Southern region). Taking into account that the different areas register different migratory trajectories (INDEC, 2010), the inclusion of these different areas becomes necessary. We selected the sample by a non-probabilistic self-selected method (Sterba & Foster, 2008). The total sample size was of 856 students (22.5% from CABA and GBA, 29.5% from Córdoba, 23.5% from Salta, and 24.5% from Neuquén). The average age was 23 years, 65,3% of the participants were women. We applied some career quotas in order to ensure the representation of different student’s profiles. In addition, we didn’t include students that identified themselves as immigrants.

Instruments

Sociodemographic and control variables: sex, age, academic unit, career, year of study, occupational status and place of residence were controlled using close-ended questions.

Subtle and Blatant Prejudice Scale: we applied an adapted Spanish version of the prejudice scale developed by Pettigrew and Meertens (1995). This version was based on the Spanish version of Rueda y Navas (1996) and the Chilean version of Cárdenas et al. (2007). We included the 20 items and 5 dimensions scale. The response format was five positions Likert type scale that asked the participant to express their level of disagreement / agreement with each statement. Thus, the Threat and Rejection (6 items) and Intimacy (4 items) dimension measured blatant prejudice, while subtle prejudice was assessed through the traditional values (4 items), cultural differences (4 items) and positive emotions (2 items) dimensions.

Assimilationism: we applied the instrument developed by Levin et al. (2012) which comprises 3 items with a 7-point Likert type response format. As this instrument was in English, prior to its application, a reverse translation and transcultural adaptation procedure was carried out following international guidelines (Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin & Ferraz, 2000).

Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA): the locally adapted version developed by Etchezahar (2014) from Altemeyer´s (1996) RWA scale was applied. This version has a two-dimensional structure consisting of 14 items with a 5-point likert response format. Here we only applied the aggression / submission dimension as it assesses perceptions about order and discipline and the role of the authorities in the restraint of groups that oppose to status quo (in this case, people culturally different from the native Argentinians).

Research Procedure

Data was collected through the individual application of a questionnaire. Prior to its administration, people were given information about the study, they were explained that the data collected would be used exclusively for academic-scientific purposes, guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality. In turn, it was emphasized that they could leave the study whenever they wished.

Data Analysis

Data was processed using SPSS 21 and AMOS 19 statistical packages. First, according to the proposal by Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham (2006) within the framework of the Classic Theory of Testing, descriptive statistics of the items were calculated: mean, standard deviation, asymmetry and kurtosis. Then, the construct validity of the scales was studied by confirmatory factor analysis using the maximum likelihood estimation method and replicating the 5-factor dimensional structure proposed by the literature. The following adjustment indexes were considered: Pearson chi-square statistic (X 2 ), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Goodness Fit Index (GFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Following the criteria proposed by Hu and Bentler (1995), values superior to .95 in CFI and GFI were considered optimal and Arbuckle's (2005) criterion of not using models whose RMSEA were greater than .08 was also followed. Subsequently, the reliability of the subscales was analyzed by estimating their internal consistency by the Cronbach's Alpha statistic. Also, to identify if there were items that reduced the reliability of the scale, we estimated the alpha coefficient when each element was eliminated. Finally, convergent validity was studied through correlation analysis between each of the subtle and blatant prejudice sub-scales and the assimilationist and RWA measurements. For that matter we estimated Pearson correlation coefficient. It is worth mentioning that prior to this procedure it was controlled that the latter also had satisfactory levels of reliability.

Results

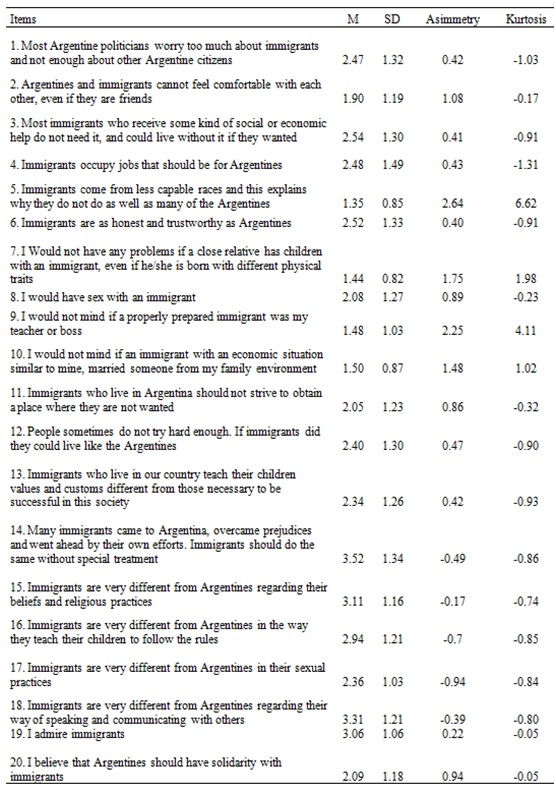

Table 1 shows the descriptive indexes for each of the items on the prejudice scale. According to the criteria established by George and Mallery (2011) to account for univariate normality, asymmetry and kurtosis values ± 2.00 are considered to be excellent and values between ± 1.00 adequate. Consequently, item 5 ("Los inmigrantes proceden de razas menos capaces y esto explica por qué no les va tan bien como a muchos de los argentines” - immigrants came from less competent races which explains why they live in worse conditions than Argentines-) and item 9 ("No me importaría si un inmigrante adecuadamente preparado fuera mi profesor o jefe” -I would not mind if a properly prepared immigrant was my teacher or boss-) were considered to be inadequate and were eliminated from subsequent analyzes.

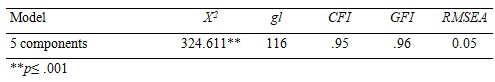

Including the 18 items that presented an adequate adjustment, we proceeded to study the construct validity through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Thus, we specified the multidimensional model of 5 components distributed according to the original proposal (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). Table 2 shows the model global adjustment indexes. Although the chi-square value yielded an unexpected result as it was statistically significant (p≤ .001), previous literature suggest that this is frequent and may be a product of the sample size (Kline, 2011). Meanwhile, the rest of the fit indexes are within the parameters established by the specialized literature, thus providing evidence of their adequacy.

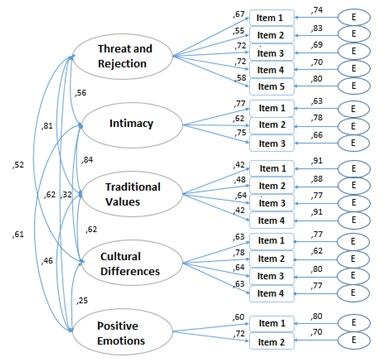

Figure 1 shows the model structure and the standardized beta coefficients that account for the load of each item on the dimension with their corresponding error terms. In all cases, the statistical significance was p≤.001.

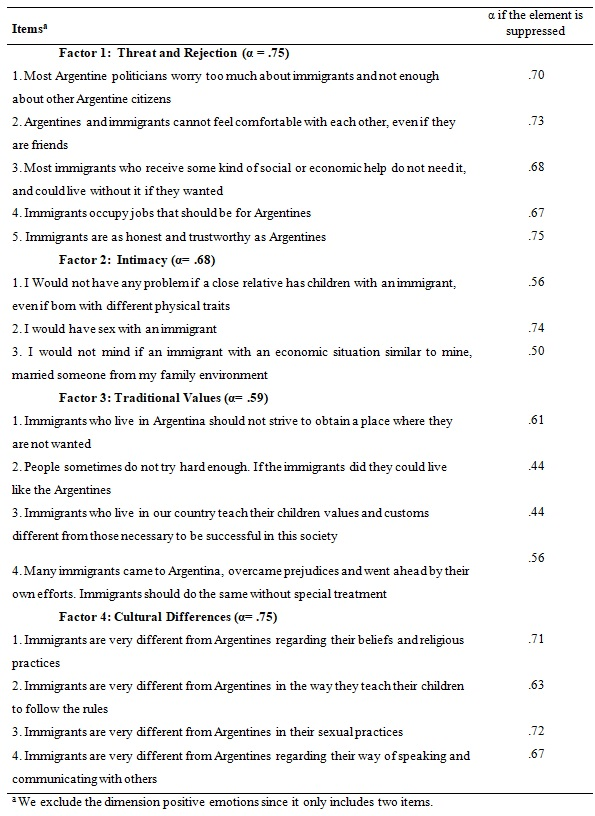

From this structure, we proceeded to the internal consistency analysis for each sub-dimensions. In addition, in order to verify the existence of items that reduce the reliability of the subscales, we estimated the Cronbach's Alpha statistic considering its variation if each element is eliminated (Table 3). As can be observed, the dimensions of blatant prejudice (threat and rejection and intimacy) obtained adequate levels of internal consistency (Maroco & García Marques, 2013). In the case of the intimacy dimension, the exclusion of the item “Tendría relaciones sexuales con un/a inmigrante” (I Would have sex with an immigrant) would increase internal consistency.

In respect of subtle prejudice, cultural differences dimension showed a satisfactory internal consistency (α = .75), while traditional values dimension was barely below the reference criterion (α = .59). In the latter case, the suppression of the item “Los inmigrantes que viven en Argentina no deberían esforzarse por hacerse un lugar donde no son queridos” (Immigrants who live in Argentina should not strive to obtain a place where they are not wanted) would increase the dimension reliability, although this increase is small (α = .61). Lastly, we could not estimate internal consistency for the positive emotions dimensions since it has only two items. Consequently, we estimated the inter-item correlation which was positive and statistically significant (r = .53; p≤ .001).

To test convergent validy, we estimated the Pearson correlation between each dimension of the prejudice scale, assimilationism and the submission / aggression dimension of RWA. The results exhibit a positive, moderate and statistically significant correlations (p≤ .01) between these variables, as expected (Table 4). This evidence indicates the adequacy of this construct for the evaluation of prejudice.

Discussion

The present study represents a significant contribution to the study of prejudice in Argentina as it provides an empirically validated instrument for addressing this phenomenon, not only in its most evident forms, but also in its more subtle aspects. More specifically, the results above presented provide evidence about the adequacy of the construct, both with respect to its structure and internal consistency and its external validity. It is important to note that most of the Spanish versions only replicated the differentiation between subtle and blatant prejudice, not being able to distinguish between different attitudinal conglomerates within each of those mentioned (Cárdenas et al., 2007; Rueda & Navas 1996). On our part, we were able to account for the multidimensional structure of the prejudice consistently with the original proposal developed by Pettigrew and Meertens (1995). This is particularly relevant since enables a more comprehensive analysis of this phenomenon.

The empirical evidence obtained regarding the internal consistency of each of these sub-dimensions indicates that the subtle aspects -especially those related to social values- seem to be more difficult to empirically assess. It is possible that, depending on the particularities of the migratory processes in each region, some of these items are ambiguous for many respondents. However, this is a hypothetical assumption and we need complementary evidence to test its adequacy (for example, application of the scale in conjunction with a cognitive interview).

It is relevant to highlight another original contribution of this study which refers to the convergent validity test. We were able to establish the relationship between our version of the subtle and blatant prejudice scale and two documented related variables (Berry, 2006; Dru, 2007; Guimond et al., 2010; Quinton, Cowan & Watson, 1996; Levin et al., 2012): Assimilationism and RWA. The correlation coefficients were more robust for some dimensions (threat and rejection, traditional values and cultural differences), while they were lower for the dimensions of intimacy and positive emotions. That is probably due to the fact that they correspond to the attitudinal aspects that emphasize less on cultural asymmetries, which are those that are more specifically evaluated trough the two convergent variables (especially the Asymilization index). On the other hand, the positive emotions index consists of only two items that can be interpreted in an ambiguous way, as they can refer (positively) to a certain empathy due to the unfavorable situation of immigrants in our country, or (negatively) to demonstrations of condescension towards those groups. Thus, it is possible that this index is not an exact approximation to the affective dimension of subtle prejudice insofar it may be biased by social desirability. However, it would be necessary to collect more empirical evidence to support this hypothesis and it would be desirable to make this measurement more complex, avoiding the evaluation of ambiguous affective aspects.

To sum up, the main findings of our study are the identification of the prevalence of prejudicial attitudes -even among young people- and the relevance of being able to evaluate the subtle dimensions of prejudice in order to achieve a better understanding of this phenomenon. Also, it allowed us to provide a locally validated measure that allows us to dialogue with the previous literature that has applied the same construct in different contexts. Also, as noted by Rueda and Navas (1996), it is possible that these measurements do not avoid the effect of social desirability, which should be controlled in future studies. For this reason, we emphasize the need to update and evaluate the adequacy of our empirical approaches in the study of complex social phenomena that are in permanent transformation.

Evidence of this is the very existence of subtle prejudice, which deepens - to the detriment of blatant expressions- as new rules are established that proscribe open expressions of prejudice and discrimination (Pettigrew & Meertens, 2001). Thus, in the last decades the indirect forms of prejudice represented new ways of preserving hierarchies based on racial, ethnic and religious dominance (Gómez Berrocal & Moya 1999). Consequently, the social function of prejudice is not only maintained, but it is reinvented in ways that -because they are less evident- become increasingly difficult to perceive, challenge and counteract. Furthermore, the use of instruments that are incapable of capturing the refined expression of prejudice could be functional to the masking of the consequences of prejudice. Thus, the illusion is created that it is an increasingly banished phenomenon of our social practices while inequality between groups is attributed to intrinsical and static attributes. Altogether, this allows to rationalize, justify and perpetuate existing hierarchies (Cárdenas et al., 2007). In this framework, the Pettigrew and Meertens (1995) scale and its adaptations, represent a valid contribution for the detection and study of new forms of prejudice in different contexts.

In addition, it is necessary to point out some methodological limitations of our research that must be taken into account for complementary studies. First, data were collected through a non-probabilistic sampling method, which limits the possibility of its generalization to the population. In addition, this instrument assesses attitudes towards immigrants as a general category, although this is not a homogeneous group and it is possible that - in accordance with prevailing hegemonic discourses - people have different attitudes towards immigrants based on aspects such as their origin. Thus, it would be relevant to compare attitudes towards European immigrants and Latin American immigrants; or towards immigrant women, given their particular difficulty in obtaining employment, which has been the subject of previous research (i.e. Andrade-Rubio, 2016; Bruno, 2016; Magliano, Perissinotti & Zenklusen, 2014). Finally, we want to emphasize the relevance of including the perspective of the immigrants themselves, who are directly suffering the consequences of prejudice and discrimination. It is essential to take into account the complexity of these phenomena and its concrete consequences for immigrants in order to devise public policies aimed to reversing situations of inequality and the achieving of real intercultural integration.

Referencias:

Arbuckle, J.L. (2005). Amos™ 6.0 User’s Guide. Pennsylvania: Amos Development Corporation [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Andrade-Rubio, K. L. (2016). Víctimas de trata: mujeres migrantes, trabajo agrario y acoso sexual en Tamaulipas.CienciaUAT,11(1, 22-36. [ Links ]

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures.Spine,25(24), 3186-3191. DOI: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 [ Links ]

Berg, J. A. (2013). Opposition to Pro‐Immigrant Public Policy: Symbolic Racism and Group Threat.Sociological Inquiry,83(1), 1-31. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-682x.2012.00437.x [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (2006). Mutual attitudes among immigrants and ethnocultural groups in Canada.International Journal of Intercultural Relations,30(6), 719-734. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.06.004 [ Links ]

Bizumic, B., & Duckitt, J. (2012). What is and is not ethnocentrism? A conceptual analysis and political implications.Political Psychology,33(6), 887-909. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00907.x [ Links ]

Blacker, D., & Endicott, J. (2002). Psychometric properties: concepts of reliability and validity. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington: American Psychiatric Association. [ Links ]

Bruno, S. F. (2016). Inserción laboral de los migrantes paraguayos en Buenos Aires. Revisión de categorías: desde el “nicho laboral” a la “plusvalía étnica”.Población y desarrollo,18(36), 7-24. [ Links ]

Campo-Arias, A., Oviedo, H. C., & Herazo, E. (2014). Correlación entre homofobia y racismo en estudiantes de medicina.Psicología desde el Caribe,31(1), 26-37. [ Links ]

Canto, J. M., Perles, F., & San Martín, J. (2012). Racismo, dominancia social y atribuciones causales de la pobreza de los inmigrantes magrebíes.Boletín de Psicología,104, 73-86. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M., Music, A., Contreras, P., Yeomans, H., & Calderón, C. (2007). Las nuevas formas de prejuicio y sus instrumentos de medida.Revista de Psicología,16(1), 69-96 [ Links ]

Cohrs, J. C., & Asbrock, F. (2009). Right‐wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice against threatening and competitive ethnic groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(2), 270-289. DOI: 10.1002/ejsp.545 [ Links ]

Chambers, J. R., Schlenker, B. R., & Collisson, B. (2013). Ideology and prejudice: The role of value conflicts.Psychological Science,24(2), 140-149. DOI: 10.1177/0956797612447820 [ Links ]

Coenders, M., Scheepers, P., Sniderman, P. M., & Verberk, G. (2001). Blatant and subtle prejudice: dimensions, determinants, and consequences; some comments on Pettigrew and Meertens. European Journal of Social Psychology,31(3), 281-297. DOI: 10.1002/ejsp.44 [ Links ]

Cosby, A., Aanstoos, K., Matta, M., Porter, J., & James, W. (2013). Public support for Hispanic deportation in the United States: the effects of ethnic prejudice and perceptions of economic competition in a period of economic distress.Journal of Population Research,30(1), 87-96. DOI: 10.1007/s12546-012-9102-9 [ Links ]

Domenech, E., & Magliano, M. J. (2008). Migración e Inmigrantes en la Argentina reciente: Políticas y Discursos de exclusión/inclusión (pp. 423-448). En M. del C. Zabala Argülles (Comp.): Pobreza, exclusión social y discriminación étnico-racial en América Latina y El Caribe. Bogotá: CLACSO. [ Links ]

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Pearson, A. R. (2017). Aversive racism and contemporary bias. En C. G. Sibley & F. K. Barlow (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the psychology of prejudice (pp. 267-294). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781316161579.012 [ Links ]

Dru, V. (2007). Authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice: Effects of various self-categorization conditions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(6), 877-883 DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.008 [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). A dual-process motivational model of ideology, politics, and prejudice.Psychological Inquiry,20(2-3), 98-109. DOI: 10.1080/10478400903028540 [ Links ]

Etchezahar, E. (2014). Las dimensiones del autoritarismo: análisis de la escala de Autoritarismo del ala de derechas (RWA) en estudiantes universitarios. Tesis para optar por el título de doctor en psicología. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Fischer, R., Hanke, K., & Sibley, C. G. (2012). Cultural and Institutional Determinants of Social Dominance Orientation: A Cross‐Cultural Meta‐Analysis of 27 Societies.Political Psychology,33(4), 437-467. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00884.x [ Links ]

Frey, D. L., & Gaertner, S. L. (1986). Helping and the avoidance of inappropriate interracial behavior: A strategy that perpetuates a nonprejudiced self-image. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(6), 1083-1090. [ Links ]

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (1986).The aversive form of racism. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press. [ Links ]

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2011). Descriptive statistics. SPSS for Windows step by step. A simple guide and reference, 18, 95-104. [ Links ]

Gómez-Berrocal, C., & Moya, M. (1999). El prejuicio hacia los gitanos: características diferenciales.Revista de psicología social,14(1), 15-40. DOI: 10.1174/021347499760260055 [ Links ]

Guimond, S., De Oliveira, P., Kamiesjki, R., & Sidanius, J. (2010). The trouble with assimilation: Social dominance and the emergence of hostility against immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations , 34(6), 642-650. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.01.002 [ Links ]

Hair J., Black W., Babin B., Anderson R. & Tatham R.L. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliff, NJ. [ Links ]

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model ²t. In Hoyley, R. H. (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: concepts, issues and applications (pp. 76-99). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo (INDEC) (2010). Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2010. Censo del Bicentenario. Pueblos originarios. Recuperado de: http://www.indec.gob.ar/publicaciones.asp [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional Contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo (INADI) (2016a). Migrantes y discriminación. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Instituto Nacional Contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo. Recuperado de: http://www.inadi.gob.ar/contenidos-digitales/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/migrantes-y-discriminacion.pdf [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional Contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo (INADI) (2016b). Racismo y xenofobia: hacia una Argentina intercultural. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Instituto Nacional Contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo. Recuperado de: http://www.inadi.gob.ar/contenidos-digitales/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/racismo-y-xenofobia-hacia-una-argentina-intercultural.pdf [ Links ]

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2003). The psychology of system justification and the palliative function of ideology.European review of social psychology,13(1), 111-153. DOI: 10.1080/10463280240000046 [ Links ]

Kessler, A. E., & Freeman, G. P. (2005). Public Opinion in the EU on Immigration from Outside the Community.JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies,43(4), 825-850. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2005.00598.x [ Links ]

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd edn). New York: Guilford Press [ Links ]

Levin, S., Matthews, M., Guimond, S., Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Kteily, N., Dover, T. (2012). Assimilation, multiculturalism, and colorblindness: Mediated and moderated relationships between social dominance orientation and prejudice.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,48(1), 207-212. DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.06.019 [ Links ]

Licata, L., Sanchez-Mazas, M., & Green, E. G. (2011). Identity, immigration, and prejudice in Europe: a recognition approach. En S. J. Schwartz, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 895-916). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

López Rita, A. M. (2017). Movilidad humana en América del Sur. Migración y derechos. Un análisis a partir de la experiencia argentina.Revista Cambios y Permanencias, 8(1), 274-288. [ Links ]

Magliano, M. J., Perissinotti, M. V., & Zenklusen, D. (2014). Mujeres bolivianas y peruanas en la migración hacia Argentina: especificidades de las trayectorias laborales en el servicio doméstico remunerado en Córdoba. Anuario Americanista Europeo, 11, 71-91. [ Links ]

Maroco, J., & Garcia-Marques, T. (2013). Qual a fiabilidade do alfa de Cronbach? Questões antigas e soluções modernas? Laboratório de Psicologia, 4(1), 65-90. [ Links ]

McConahay, J. B., Hardee, B. B., & Batts, V. (1981). Has racism declined in America? It depends on who is asking and what is asked.Journal of conflict resolution,25(4), 563-579. DOI: 10.1177/002200278102500401 [ Links ]

McConahay, J. B., & Hough, J. C. (1976). Symbolic racism.Journal of social issues,32(2), 23-45.DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1976.tb02493.x [ Links ]

Minero, L. P., & Espinoza, R. K. (2016). The influence of defendant immigration status, country of origin, and ethnicity on juror decisions: An aversive racism explanation for juror bias.Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,38(1), 55-74. DOI: 10.1177/0739986315620374 [ Links ]

Monsegur, S., Espinosa, A., & Beramendi, M. (2014). Identidad nacional y su relación con la dominancia social y la tolerancia a la transgresión en residentes de Buenos Aires (Argentina). Interdisciplinaria, 31(1), 5-23. [ Links ]

Muller, M., Ungaretti, J., & Etchezahar, E. (2017). Validación argentina de la Escala de Prejuicio Sutil y Manifiesto hacia villeros.Revista de psicología (Santiago),26(1), 1-13. [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Serrano, F. J., Aguilera, R. E., & Rodríguez, A. (2013). Estereotipos Mediáticos o sociales. Influencia del consumo de televisión en el prejuicio detectado hacia los indígenas mexicanos.Global Media Journal México, 7(14). [ Links ]

Pettigrew, T. F. y Merteens, R. W. (1992). Le racisme voile: dimensions et mesures. En M. Wieviorka (Ed.). Racisme et modernité. (pp. 109-126) Paris: La Decouverte. [ Links ]

Pettigrew, T. F., & Meertens, R. W. (1995). Subtle and blatant prejudice in Western Europe.Europeanjournal of social psychology,25(1), 57-75. DOI: 10.1002/ejsp.2420250106 [ Links ]

Pizarro, C. A. (2012). El racismo en los discursos de los patrones argentinos sobre inmigrantes laborales bolivianos: Estudio de caso en un lugar de trabajo en Córdoba, Argentina. Convergencia,19 (60), 225-285. [ Links ]

Quinton, W. J., Cowan, G., & Watson, B. D. (1996). Personality and Attitudinal Predictors of Support of Proposition 187-California's Anti‐Illegal Immigrant Initiative.Journal of Applied Social Psychology,26(24), 2204-2223. DOI: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01796.x [ Links ]

Ramirez Barría, E., Estrada Goic, C., & Yzerbyt, V. (2017). Estudio correlacional de prejuicio y discriminación implícita y explícita en una muestra magallánica.Revista Atenea, 513, 251-262. [ Links ]

Rubalcaba, D. H., & Quintero, C. S. (2013). Tipología y grado de prejuicio de un grupo de españoles hacia el colectivo colombiano. Una lectura con perspectiva de género.Educación y Humanismo, 15(24). [ Links ]

Rueda, J. F., & Navas, M. (1996). Hacia una evaluación de las nuevas formas del prejuicio racial: las actitudes sutiles del racismo.Revista de Psicología Social,11(2), 131-149. DOI: 10.1174/02134749660569314 [ Links ]

Sánchez, J. (2014). The Perception of the Economy Influencing Public Opinion on Immigration Policy. e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work, 2(3), 119-128. [ Links ]

Sar, R. A. (2016). La construcción mediática de los inmigrantes en Iberoamérica.Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo (RICD), 1(3), 25-39. [ Links ]

Sterba, S. K., & Foster, E. M. (2008). Self-selected sample. Encyclopedia of survey research methods, 806-808. [ Links ]

Ungaretti, J. (2017). La evaluación del prejuicio sutil y manifiesto hacia colectivos indígenas e inmigrantes de países limítrofes. Calidad de Vida y Salud, 10(1), 57-68. [ Links ]

Valverde, S. (2015). El estigma de la difusión y la difusión del estigma. La escuela histórico-cultural y los prejuicios hacia los pueblos indígenas de norpatagonia, Argentina.Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología,40(1), 327-349. [ Links ]

Vélez, F. R., & Maluf, N. A. (2017). Después de la negación: el Estado argentino frente al racismo y la discriminación.Cuadernos del CENDES,34(95), 155-182. [ Links ]

Received: July 12, 2018; Revised: February 27, 2019; Accepted: April 11, 2019

texto em

texto em