Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.12 no.2 Montevideo nov. 2018

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1692

Short Communication

Psychological assessment in the forensic field: early release in the Uruguayan context

1Departamento de Psicología Social y Organizacional, Facultad de Psicología. Universidad Católica del Uruguay, lbarboni@ucu.edu.uy

2Instituto Nacional de Criminología, Ministerio del Interior. Uruguay, bonillan@vera.com.uy Correspondencia: Lucía Barboni Pekmezian. Comandante Braga 2715, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Católica del Uruguay. Natalia Bonilla Armada. Instituto Nacional de Criminología. I.N.R. Ministerio del Interior, Montevideo, Uruguay. Agraciada 4129, Montevideo.

Keywords: hazard; risk assessment; forensic assessment; psychological expertise; prison

Palabras clave: peligrosidad; evaluación de riesgo; evaluación forense; pericia psicológica; cárcel

Introduction

Tejero (2016) defines the role of “experts” (peritos) as the professional exercise of issuing an opinion with evidential value, arising from the knowledge inherent to the expert’s science, with a specific demand and with the purpose of assisting the judge. In the Uruguayan General Procedure Code, expert evidence is used when special scientific, artistic or technical knowledge is required (Law Nº 15982;1988).

Forensic psychological expert examination is defined as an instrument to provide advice to the judicial authority, through an opinion based on a thorough assessment in a specific area and with a particular aim (Ching, 2005). Although it is important to underscore that expert reports are not binding for judges, they are still a highly relevant auxiliary element for them (Tejero, 2016).

For the purpose of having certain procedure parameters during expert assessments, there is a Manual prepared by expert psychologists of the Medical-Criminological department of the Technical-Forensic Institute of the Uruguayan Judicial Branch (hereinafter, the I.T.F., as per its acronym in Spanish). This manual states that the professional must take into consideration certain characteristics when assessing the person, such as: the fact that the subject is not willingly submitting him/herself to the assessment, stress caused by court proceedings, and the subject’s need to present him/herself positively, which increases desirability bias and margin of error in tests (Instituto Técnico Forense,1998; Muñoz, 2013; Echeburúa, Muñoz, & Loinaz, 2011).

In the Uruguayan context, expert psychologists provide advice to criminal justice administration in the different stages of the process, from initial stages for the verification of criminal facts, until the resolution for the possible granting of an early release.

Although the semi-structured expert interview is the main and mostly used instrument during the assessment process, professionals need to have other tools to reduce the impact of the subjective variable, trying to reach objective conclusions for the resolution of assessments.

With the purpose of planning and carrying out an assessment aimed at providing an answer with respect to the presence of potential static and dynamic risk and/or protective factors (Arbach et al., 2015) within the framework of the consequences of access to the benefit of early release, it is worth providing readers with some information about what is established by regulations. The National Institute of Criminology (hereinafter, I.NA.CRI., as per its acronym in Spanish) works as of this date within the National Rehabilitation Institute (hereinafter, I.N.R., as per its acronym in Spanish). The National Center of Criminological Opinions is in charge, among other things, of conducting assessments of individuals deprived of their liberty applying for an early release, in accordance with Art. 328 of the Criminal Procedure Code (hereinafter, C.P.P. as per its acronym in Spanish). This process (until October 31st 2017) mandatorily required an expert examination carried out exclusively by technicians of the Institute, and such examination would result in a Personality and Dangerousness assessment (Instituto Técnico Forense, 1998) aimed at analyzing the subject’s current psycho-social functioning towards deciding whether or not to recommend access to such benefit. This was only a non-binding psychological opinion; the actual granting or denial of early release was the competence of the Supreme Court of Justice (hereinafter, S.C.J.).

Before the recent reform, the C.P.P. stated in its article 328 that the S.C.J. may grant early release in the following cases: If the sentence is of up to 24 months and the person has already served half of the sentence; if the sentence is of at least 2 years or a fine, whatever the time served; if the person has served two thirds of the sentence. It may only be denied on reasonable grounds, in cases where the person does not show evident signs of rehabilitation. In any case, the mandatory report carried out by I.NA.CRI. is required.

However, the C.P.P. had a new wording introduced by Law No. 19,293 (2015) where it is expected that the benefit of early release may be granted to sentenced persons, who, being deprived of their liberty, can be formulated a favorable prognosis of social reintegration taking into account their behavior, personality, form and conditions of life. It is considered that: if the sentence relapses out of prison, you may request it at any time; if the sentence was a penitentiary, it may be requested it having served half of the sentence; in the event that the penalty of penitentiary has been added to eliminative security measures, it may be requested after it has reached two thirds of the penalty. This modification of the Law supplants the expertise for the technical report referring to the re-socialization skills of the prisoner, leaving aside the exclusive competence of the I.NA.CRI in the evaluation for the Anticipated Freedom (Article 229; Law Nº 19293, 2015). Subsequently, the judge of Enforcement and Surveillance will decide before the Public Prosecutor's Office, disposing of: the report of prison conduct and the technical reports that are available referring to the re-socialization skills of the prisoner; the reassessment of the penalty for work and study, and the updated criminal record. In this way we seek to modify a procedure that until now seemed to be very extensive since not only the expert assessment carried out by the I.NA.CRI., but also the S.C.J. which will decide whether or not to grant early release.

Violent behavior has been considered as one of the most characteristic elements of serious crime and, in connection with this, the level of dangerousness attributed to those who have committed serious crimes has been used as an explanatory and predictive argument, both for the seriousness of criminal acts, as for recidivism (Andrés-Pueyo & Arbach, 2014; Andrés-Pueyo & Redondo, 2007), both matters directly linked to the assessment for early release.

The historically debated concept of “dangerousness” refers to the individual’s propensity to commit dangerous and violent acts, summarizing it with apparent clarity as the quintessential predictor of future violent behavior (Scott & Resnick, 2006). It assumes a static quality, a psychological disposition (Arbach & Andrés-Pueyo, 2007) which might become highly stigmatizing for the subject under assessment, this being a clinical opinion reached idiosyncratically and with conceptualization deficiencies (Arbach et al., 2015). Since the development of criminological psychology has shown the limited and inefficient predictive ability of the concept of dangerousness to make prospective decisions in clinical, forensic or prison contexts, the use of the risk-assessment concept has been promoted at international level (Andrews & Bonta, 2003).

Violent behavior risk assessment, as an alternative to the dangerousness diagnosis (as a predictor of violent behavior), states that each type of violence has its own specific risk and protective factors (Andrés-Pueyo & Echeburúa, 2010) and that the way in which violent behavior assessment is carried out and in which intervention is planned has a direct impact on court decisions, social welfare and professional work (Ochoa-Balarezo et al., 2017).

Both in formal and informal contexts there is a social interest to know about and predict violent behavior in individuals; in addition, there is a need to systematize empirically-based criteria, in order to carry out such predictions (Folino & Escobar, 2004). Certain individual psychological characteristics (personality traits and psycho-social skills) are considered as risk factors that have an impact on violent behavior, predisposing the individual to anti-social behaviors. When these behaviors are combined with certain social factors, they give rise to serious or extreme violent behavioral expressions. Knowing the action mechanisms of risk factors, triggering factors and the interaction between them (opportunity, context, characteristics of the case) allows us to predict and prevent violent behavior (Andrés-Pueyo & Redondo, s.f; Loinaz, 2017), which is especially useful for early release assessments.

The creation of multiple violent behavior risk assessment guides during the past decades and the increasing adaptation thereof at an international level are evidence of the changes that have been taking place in assessment systems. Research at an international level shows concern for the systematization of violence risk assessment and, as a consequence, for the planning and monitoring of interventions aimed at preventing recidivism in this kind of behavior (Ochoa-Balarezo et al., 2017).

The use of risk assessment instruments has become a usual procedure for psychologists in the United Kingdom, Australia, United States and Denmark; however, there is a greater trend towards actuarial tools, rather than to structured clinical judgment tools (Singh et al., 2014). Said instruments make it easier to receive and critically review actors in the system, making both assessment as decision-making processes more transparent (Muñoz & López-Ossorio, 2016).

According to a survey (Viljoen, McLachlan, & Vincent, 2010), the nine mostly used instruments include: Assessing Risk for Violence-HCR-20 (Douglas, Hart, Webster, & Belfrage, 2013) Sexual Violent Risk-SVR-20 (Boer, Hart, Kropp, & Webster, 1998), Spousal Assault Risk Assessment Guide- SARA (Kropp & Hart, 2000) and Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth -SAVRY (Borum, Bartel, Forth, 2003); Level of Service Inventory-revised- LSI-R (Andrews & Bonta, 1995), theHare Psychopathy Checklist- revised- PCL-R (Hare, 2003), Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide- SORAG (Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 1998), Static-99 (Hanson & Thornton, 1999) and Violence Risk Appraisal Guide- VRAG (Harris, Rice, & Quinsey, 1993).

There is a vast body of research on such instruments which reflects the importance of including them in new procedures (Viljoen et al., 2010; Gacono, 2000; Arbach et al., 2015; Fazel et al., 2012; Loinaz, 2017). Although the general picture in Latin America shows that risk development tools are at a budding stage of development, the use of other type of instruments still prevails (Singh, Condemarín, & Folino, 2013; Arbach, et al., 2017).

This paper is aimed at bringing us closer to the situation of forensic psychological expert assessment in individuals who applied for the benefit of early release, based on a documentary review of national records.

Documentary Review

This documentary review collected information from records of the data base of I.NA.CRI. from 2013 to 2017. The following data were inquired:

Number of individuals assessed by experts per year

Type of crime appearing in the file cover

Prison where the person was assessed

Professional training of I.NA.CRI technicians

Type of recommendation by I.NA.CRI technicians

Once these data were obtained, resolutions by the S.C.J. published in the Statistics section of the website of the Judicial Power (Judicial Power, 2017) were analyzed in relation to the number of early releases granted and the number of early releases denied, in general.

Results

Based on the documentary study carried out on the records of people who were psychologically assessed in the face of the request for early release within the framework of the criminal process in Uruguay, the results that arise from the review of the records included in the records control system are presented together with the assessments carried out by the I.NA.CRI, like the resolutions that the SCJ takes in the same periods (Judicial Power, 2017) regarding the granting of anticipated freedoms between the years 2013 and 2017.

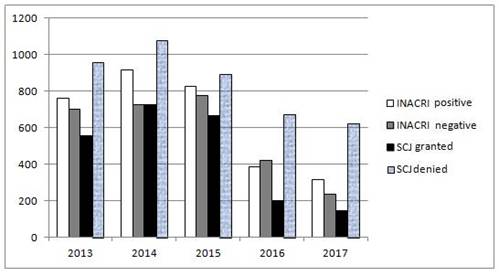

Figure 1 shows the totality of annualized assessments with favorable recommendation (positive reports) and unfavorable (negative reports) to obtain the benefit by I.NA.CRI. In relation to the resolutions of the S.C.J.2, all the concessions and denials of anticipated freedom are also included on an annualized basis.

In year 2013, technicians recommended granting 736 early release applications, while they recommended denying such benefit in 701 cases. In the same year, the S.C.J. granted 554 early releases and denied 961.

In year 2014, there were 915 positive recommendations and 727 negative recommendations. The S.C.J. granted 728 early releases and denied 1078.

In year 2015, there were 828 favorable recommendations and 778 unfavorable recommendations. The S.C.J. granted 666 early releases and denied 894.

Between 2013 and 2015, there were more positive recommendations regarding access to the benefit of early release than negative recommendations. However, the situation changed in 2016, when there were 420 negative reports and 384 positive reports. In this year, the S.C.J. granted 201 early releases and denied 676.

Finally, in year 2017, the S.C.J. granted 147 early releases and denied 625, while I.NA.CRI. issued 316 positive reports and 237 negative reports.

Discussion

The study was aimed at describing the characteristics and procedures inherent to the role of psychologists as court advisors in early release applications in Uruguay, through a theoretical review of the issue and the presentation of figures referring to expert assessments conducted between 2013 and 2017, which problematize the need to review professional practices in accordance to what international publications recommend in terms of forensic-psychological expert assessments. The main aim was to show, for the first time, information relative to the Uruguayan general situation as for psychological expert assessments for early release applications.

With regard to preliminary findings of this documentary review, the analysis of expert assessments carried out reflects a need to computerize reports with higher quality; results show a decrease in the number of expert assessments and resolutions which responds to - among other things - a need for more human resources, as well as to the lack of guides to direct professional practices.

It was also found that, except for a few exceptional cases, the only technique used was interviews. Although there are claims that tests and other assessment techniques aimed at greater objectivity have to be used carefully, based on planning that takes into consideration their use, application time, scientific quality and limitations, risk assessment instruments in the field of expert assessment are advantageous in many ways (Muñoz & López Ossorio, 2016).

The documentary review showed a lack of criteria for the unification of concepts such as rehabilitation, progressivity, re-socialization process or vulnerability to crime. In addition, we observed minimum use of specific assessment tools of the forensic field taking into account the specific characteristics of the population assessed. Results also reflect the difficulties faced daily by technicians when they assess a discharge plan (as a risk factor and as a protective factor) when individuals assessed lack social networks or any chances to enter the labor market in a stable and formal manner after they leave prison. More importantly, the thoroughness required to show a possible relation between a personality structure and a criminological prognosis.

From February 2013 to December 2017, the S.C.J. granted 2296 early releases, there being a total of 3179 favorable recommendations and 2863 unfavorable recommendations by I.NA.CRI. The number of assessments made does not correspond with the number of resolutions issued by the S.C.J., possibly due to a lag in processing times, which is a weakness when it comes to analyzing the correlation between data. Since this is a resolution that implies access by subjects to their freedom of movement before serving their full sentence, taking into account the different repercussions of this (mainly regarding more violent crimes), and that in most cases (except in 2017) S.C.J. resolved in favor of positive reports, the scientific quality of expert assessments is valued as highly relevant and they have evidential value for the S.C.J.

Taking into consideration the complexity of the role of experts, the lack of local bibliographical sources and consultation with qualified informants, it becomes clear that I.NA.CRI. does not have, to this date, a formal professional practice guide available to the public, to guide, suggest and standardize the step-by-step process for forensic-psychological assessments. However, in the field of forensic psychology and in different areas, there are significant and highly recommended guides for professionals (Colegio Oficial de Psicólogos de Madrid, 2009; Asociación de Psicólogos Forenses de la Administración de Justicia, 2018; American Psychological Association, 2013; Colegio Oficial de Psicología de Catalunya, 2014; Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, 2010; Fiscalía de Chile, 2008; Ruiz, 2014; Instituto de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, 2016; Poder Judicial, 2008).

The creation of professional practice guides, the implementation of forensic assessment tools adapted to our population, which allow professionals to unify assessment criteria and optimize results obtained, a better systematization of data and the promotion of research in this field, are necessary adjustments to continue developing this area.

One of the main reviews to current practices that is worth pointing out is the urgency to understand that the role of experts, as indicated by the concept itself, indicates a specialty in a specific area and this forces professionals in this role to have specific training addressing particular aspects of the field.

Working from the perspective of violent behavior risk assessment instead of estimating levels of dangerousness implies not only a step forward in terms of the thoroughness of the expert’s work, but also a way of thinking about how to manage this risk taking into account that it is dynamic, situational; in other words, taking into consideration that there are several risk factors that have an impact, apart from individual factors. Nevertheless, it is worth emphasizing that it is important for technicians to know tools and to be able to select the adequate tool for each case, paying special attention to the predictive effectiveness thereof, but also to the accuracy required to define what will be assessed, for what purpose and how.

The apparent transition towards a better overall picture in Latin American practices (Singh, Condemarín, & Folino, 2013) should be an incentive when it comes to future research, and Uruguay cannot miss out on this challenge.

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association (2013). Specialty Guidelines for Forensic Psychology. American Psychologist. 68(1), 7-19. DOI: 10.1037/a0029889 [ Links ]

Andrés-Pueyo, A. & Arbach, K. (2014). Peligrosidad y valoración del riesgo de violencia en contextos forenses. En E. García-López. (Ed.), Psicopatología Forense: comportamiento humano y tribunales de justicia. (pp. 505-525). Bogotá: Editorial El Manual Moderno Colombia. Recuperado de https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucusp/detail.action?docID=3223956 [ Links ]

Andrés-Pueyo, A. & Echeburúa, E. (2010). Valoración del riesgo de violencia: instrumentos disponibles e indicaciones de aplicación. Psicothema, 22, 403-409. Recuperado de http://www.psicothema.com/PDF/3744.pdf [ Links ]

Andrés-Pueyo, A. & Redondo, S. s.f Aportaciones psicológicas a la predicción de la conducta violenta: reflexiones y estado de la cuestión. Departamento de personalidad. Grupo de Estudios Avanzados en Violencia (GEAV). Universidad de Barcelona: España. Recuperado de http:// www.ub.es/personal/geav.htm [ Links ]

Andrés-Pueyo, A. & Redondo, S. (2007). La predicción de la violencia: entre la peligrosidad y la valoración del riesgo de violencia. Papeles del Psicólogo, 28, 157-173. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/778/77828301.pdf [ Links ]

Andrews, D., Bonta, J. (1995). LSI-R: The Level of Service Inventory-Revised. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems Inc. [ Links ]

Andrews, J., Bonta, R. (2003). The psychology of criminal conduct (3rd. Ed.). Cincinnati: Anderson Pub. Cgo. [ Links ]

Arbach, K. & Andrés-Pueyo, A. (2007) Valoración del riesgo de Violencia en enfermos mentales con el HCR-20Papeles del Psicólogo , 28(3), 174-186. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/778/77828301.pdf [ Links ]

Arbach, K., Dezmarais, S. L. , Hurducas, C., Condemarin, C., Dean, K., Doyle, M., Folino, J.O. … Singh, J.P. (2015). La práctica de la evaluación de riesgo en España. Revista de Facultad de Medicina, 63(3), 357-366. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v63n3.48225 [ Links ]

Arbach, K., Bondaruk, A., Carubelli, S., Palma-Vegar, M. F., & Singh, J. P. (2017). Evaluación forense de la peligrosidad: Una aproximación a las prácticas profesionales en Latinoamérica. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencia Psicológica, 9(1), 1-15. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5872/psiencia/9.1.23 [ Links ]

Asociación de Psicólogos Forenses de la Administración de Justicia (2018). Evaluación psicológica forense de los abusos y maltratos a niños, niñas y adolescentes. Guía de buenas prácticas. España. Recuperado de http://copmelilla.org/descargas/pdf/guiebuenaspracticasymaltratoinfantil.pdf [ Links ]

Boer, D., Hart, S., Kropp, P., & Webster, C. (1998). Manual for the Sexual Violence Risk-20. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. [ Links ]

Borum, R., Bartel, P., & Forth, A. (2003). Manual for the Structured Assessment for Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [ Links ]

Ching, R. (2005). Psicología Forense: Principios fundamentales. Recuperado de https://books.google.com.uy/books?id=bSd3q_EuXW0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Ching,+R.+(2005).+Psicolog%C3%ADa+Forense:+Principios+fundamentales.+(Primera+reimpresi%C3%B3n).+San+Jos%C3%A9,+Costa+Rica:+Editorial+Universidad+Estatal+a+Distancia.&hl=es419&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false [ Links ]

Colegio Oficial de Psicólogos de Madrid (2009). Guía de buenas prácticas para la elaboración de informes psicológicos periciales sobre custodia y régimen de visitas de menores. Madrid. Recuperado de http://www.copmadrid.org/webcopm/recursos/guia_buenas_practicas_informes_custodia_y_regimen_visitas_julio2009.pdf [ Links ]

Colegio Oficial de Psicología de Catalunya (2014). Guía de buenas prácticas para la evaluación psicológica forense y la práctica pericial. Catalunya. Recuperado de http://www.infocop.es/pdf/guiaforense2014.pdf . [ Links ]

Douglas, K. S., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Belfrage, H. (2013). HCR-20 (Version 3): Assessing Risk for Violence. Burnaby, BC, Canada: Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University. [ Links ]

Echeburúa, E., Muñoz, J.M., & Loinaz, I. (2011). La evaluación psicológica forense frente a la evaluación clínica: propuestas y retos de futuro. International Journal of Clinic and Health Psychology, 11(1), 141-159. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/337/33715423009.pdf [ Links ]

Fazel, S., Singh, J., Doll, H, & Grann, M. (2012). Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24827 people. Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 24(345). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4692 [ Links ]

Fiscalía de Chile (2008). Evaluación pericial psicológica de credibilidad de testimonio. Documento de trabajo interinstitucional. Santiago de Chile. Recuperado de http://www.fiscaliadechile.cl/Fiscalia/archivo?id=625&pid=60&tid=1 [ Links ]

Folino, J.O., & Escobar Córdoba, F. (2004). Nuevos aportes a la evaluación de riesgo de violencia. MedUnab, 7(20), 99-105. Recuperado de https://revistas.unab.edu.co/index.php/medunab/article/view/227/210 [ Links ]

Gacono, C. (2000). The clinical and forensic assessment of Psychopathy: A practitioner’s guide. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum [ Links ]

Hanson, R. K., & Thornton, D. (1999). Static-99: Improving actuarial risk assessments for sex offenders. User Report 99-02. Ottawa: Department of the Solicitor General of Canada. [ Links ]

Hare, R. (2003). The Hare Psychopathy Checklist - Revised Manual. 2nd ed. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, Inc. [ Links ]

Harris, G.T., Rice, M.E., & Quinsey, V.L. (1993). Violent recidivism of mentally disorders offenders: the development of a statistical prediction instrument. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 20, 315-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854893020004001 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (2010). Guía para la realización de pericias psiquiátricas y psicológicas forenses mediante autopsia psicológica en la determinación de la manera de muerte (suicida, homicida o accidental). Bogotá. Recuperado de http://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/documents/20143/40473/Gu%C3%ADa+para+la+realizaci%C3%B3n+de+pericias+psiqui%C3%A1tricas+o+psicol%C3%B3gicas+forenses+mediante+autopsia+psicol%C3%B3gica+en+la+determinaci%C3%B3n+de+la+manera+de+muerte+suicida%2C+homida+.pdf/3e166326-5933-7734-5b32-a80171456ac3 [ Links ]

Instituto de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (2016). Guía de evaluación psicológica forense en casos de violencia contra las mujeres y los integrantes del grupo familiar; y en otros casos de violencia. Lima. Recuperado de https://portal.mpfn.gob.pe/descargas/Guia_04.pdf [ Links ]

Instituto técnico Forense, (1998). Poder Judicial del Uruguay. Manual del Instituto Técnico Forense. Montevideo. [ Links ]

Kropp, P.R. & Hart, S. D. (2000). The Spousal Assault Risk Assessment (SARA) Guide: Reliability and validity in adult male offenders. Law and Human Behaviour, 24, 101-118. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005430904495 [ Links ]

Ley Nº 15982. Código General del Proceso. Uruguay, 14 de noviembre de 1988. Recuperado de https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/codigo-general-proceso/15982-1988 [ Links ]

Ley Nº 19.293. Código del Proceso Penal. Uruguay, 9 de enero de 2015. Recuperado de https://legislativo.parlamento.gub.uy/temporales/leytemp6967303.htm [ Links ]

Loinaz, I. (2017). Manual de evaluación del riesgo de violencia. Madrid, España: Ediciones Pirámide. [ Links ]

Muñoz, J.M. (2013). La evaluación psicológica forense del daño psíquico: propuesta de un protocolo de actuación pericial. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 23, 61-69. Recuperado de http://www.copmadrid.org/webcopm/publicaciones/juridica/jr2013v23a10.pdf [ Links ]

Muñoz, J. M., & López- Ossorio, J.J. (2016). Valoración psicológica del riesgo de violencia: alcance y limitaciones para su uso en el contexto forense. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 26, 130-140. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apj.2016.04.005 [ Links ]

Ochoa-Balarezo, J.V., Guillén, X.K., Ullauri-Ortega, Narváez, J.L., León-Mayer, E., & Folino, J. (2017) Sistematización de la evaluación de riesgo de violencia con instrumentos de juicio profesional estructurado en Cuenca, Ecuador. Maskana, 9(1), 1-14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18537/mskn.08.01.01 [ Links ]

Poder Judicial (2008). Evaluación y recomendaciones para la elaboración de peritajes psicológicos y psiquiátricos en el Poder Judicial. San José, Costa Rica. Recuperado de https://www.poder-judicial.go.cr/violenciaintrafamiliar/index.php/de-su-interes?download=384:peritajespsicolpsiquiatpj [ Links ]

Poder Judicial (2017). Estadísticas. Sección Libertades y Visitas de Cárceles (enero a diciembre de 2017). Uruguay. Recuperado de http://poderjudicial.gub.uy/images/Estad%C3%ADsticas_Enero_a_diciembre_2017.pdf [ Links ]

Quinsey, V. L., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Cormier, C. A. (1998). Violent offenders: Appraising and managing risk. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Ruiz, J.I. (Ed.) (2014). Manual para la formulación, diseño y evaluación de programas penitenciarios. Bogotá: Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho, Instituto Nacional Penitenciario y Carcelario-INPEC y Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Laboratorio de Psicología Jurídica. [ Links ]

Scott, C. L., & Resnick, P. J. (2006). Violence risk assessment in persons with mental illness. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 11(6), 598-611. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.12.003 [ Links ]

Singh, J. P., Desmarais, S. L., Hurducas, C., Arbach, K., Condemarin, C., Dean, K., Doyle, M. … Otto, R. K. (2014). International perspectives on the practical application of violence risk assessment: a global survey of 44 countries. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 13(3), 193-206. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2014.922141 [ Links ]

Singh, J. P., Condemarín, C., & Folino, J. (2013). El uso de instrumentos de evaluación de riesgo de violencia en Argentina y Chile. Revista Criminalidad, 55(3), 279-290. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/crim/v55n3/v55n3a06.pdf [ Links ]

Tejero, R. (2016). Ejercicio profesional del psicólogo forense y pautas para el orientador. TSOP: Psicología forense y justicia social: estrategias de intervención, 10, 10-24. Recuperado de https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucusp/reader.action?docID=4823934 [ Links ]

Viljoen, JL., McLachlan, K., & Vincent, GM. (2010). Assessing violence risk and psychopathy in juvenile and adult offenders: a survey of clinical practices. Assessment, 17, 377-95. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191109359587 [ Links ]

Received: March 06, 2017; Revised: August 07, 2018; Accepted: September 11, 2018

texto en

texto en