Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

Ciencias Psicológicas

Print version ISSN 1688-4094On-line version ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.12 no.2 Montevideo Nov. 2018

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1689

Original Articles

Subjective well-being of children and adolescents: Integrative review

1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia. Universidade de Fortaleza. Brasil,rebecafflima@gmail.com, normandaaraujo@gmail.com Correspondência: Rebeca Fernandes Ferreira Lima, Araujo de Morais Universidade de Fortaleza. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia. Avenida Washington Soares, 1321, Edson Queiroz. CEP: 60.811-905. Fortaleza, CE. E-Mail: rebecafflima@gmail.com. Normanda Araujo de Morais, e-mail: normandaaraujo@gmail.com

Keywords: life satisfaction; positive affect; negative affect; positive psychology; integrative review

Palavras-chave: satisfação de vida; afeto positivo; afeto negativo; psicologia positiva; revisão integrativa

Palabras-clave: satisfacción con la vida; afecto positivo; afecto negativo; psicología positiva; revisión integradora

Introduction

There are an increasing amount of studies on positive psychological indicators and in the movement entitled Positive Psychology, whose focus is the research and promotion of happiness, it is hope, creativity and other characteristics that drive healthy development (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). In this context, research on well-being is being developed that is based on different philosophical currents, which are the hedonic and eudaimonic paradigms, implying different conceptions of well-being.

The hedonic perspective is based on subjective well-being (SWB) (Diener, 1984), in which there is a focus on the perception of happiness, life satisfaction (LS) and the positive balance between pleasurable and unpleasant emotions. The SWB is defined by individual and subjective assessments that include cognitive judgment of life satisfaction (LS) and emotional reactions (positive affect - PA and negative affect - NA) to life events. From this perspective, the SWB is approached from bottom-up theories, which propose that the explanation of well-being comes from the influence of external factors, situations and sociodemographic variables; and the top-down theories, which have an emphasis on subjective variations, such as personality traits, in determining well-being. Thus, there are the influences of genetic factors and social conditions on well-being (Diener, Oishi, & Tay, 2018).

The eudaimonic perspective is the basis for psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989), and presents a set of psychological capacities and resources that people need to function fully and realize their potential. This is a conception that originates from questions about SWB indicators, with the argument that previous research has neglected positive psychological functioning. This proposal listed six dimensions for understanding well-being: self-acceptance, positive relationships with others, autonomy, mastery over the environment, purpose in life, and personal growth. Keyes (1998), who was also interested in the successful functioning of people, investigated the influence of social indicators on welfare assessments, conceiving of social welfare. This addresses five dimensions, which are social integration, social contribution, social coherence, social updating and social acceptance. Keyes (2002) proposed that measurements of emotional well-being, psychological well-being and social well-being collectively make up mental health. There are also studies on personal well-being (Cummins, 2010) defined by the subjective evaluation of quality of life in seven domains related to satisfaction with different areas of life, these are satisfaction with health, living standards, things achieved, safety, security about the future, relationships with other people and with belonging to the community. Studies in this area highlight relationships in immediate environments, such as activities involving family, peers, and neighborhood security that are more consistently related to levels of well-being (Lee & Yoo, 2015).

The perspectives (hedonic and eudaimonic) differ in the understanding of well-being. And while the interrelation between them is not denied, as Ryan and Decy (2001) argued, the importance of demarcating different conceptions of well-being is emphasized. For example, SWB was commonly used as a synonym for happiness, however, it was found that people who experience NA can have high levels of happiness and not every PA leads to increased happiness (Damásio, Zanon, & Koller, 2014). Casas (2015) compared different psychometric scales of well-being with children and adolescents from 15 countries (e.g., Spain, Nepal, Israel), identifying clear differences in well-being assessment with variations between ages and sociocultural contexts. Given this empirical evidence and the theoretical studies that mention the difficulty of defining the concept of well-being (e.g., Pureza, Kuhn, Castro, & Lisboa, 2012; Scorsolini-Comin & Santos, 2010), it is therefore relevant to study the growing scenario of research on SWB. There are also advances in the literature that sought to test whether hedonia and eudaimonia can represent a global well-being construct or two related dimensions, identifying that this global perspective is obtained with more precision when measured by self-reported subjective and psychological well-being (Disabato et al., 2016).

This article aims to prioritize references of methodological models that consider SWB in the affective (PA and NA) and cognitive (LS) dimensions in researches with children and adolescents, mainly because it is recognized that the literature has prioritized the population of adults and the elderly, and there are few studies about SWB in children/adolescents (Casas et al., 2013). This population has traditionally been described in theories centered on psychopathologies and behavioral problems. However, this view has been deconstructed from the emergence of contextualized conceptions of development and studies that increasingly value their positive aspects (e.g., Baptista, Filho, & Cardoso, 2016, Lima & Morais, 2016a; 2016b).

Based on the previous considerations regarding the lack of consensus in the definition of SWB and the scarcity of studies on this subject in the child and adolescent population, this study aims to carry out an integrative review of the national and international literature, considering the period from 2005 to 2016, on the subjective well-being of children and adolescents. For this, we chose to use the SWB concept, as defined by Diener (1984), a criterion already used in a meta-analysis study on SWB and life events (Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid, & Lucas, 2012).

Method

Study type. This is an integrative review that aims to summarize the studies carried out on a certain subject that investigate the same or similar problems and analyze them in a systematic way (Pompeu, Rossi, & Galvão, 2009). Thus, conclusions and reflections are constructed for future research, based on the results demonstrated in each study. To implement this review, eight steps were followed (Costa & Zoltowski, 2014): 1) Delimitation of the question to be researched; 2) Choice of data sources; 3) Choice of the keywords for the search; 4) Search and storage of results; 5) Selection of articles by abstract, according to inclusion and exclusion criteria; 6) Extraction of the data from the selected articles; 7) Evaluation of articles; and 8) Synthesis and interpretation of data. The PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) (Liberati et al., 2009) were also followed.

Index bases and uniterms used. The search for articles in indexed scientific journals was done using the following databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, SciELO, PEPSIC, LILACS and IndexPsi. The search terms used were: “("subjective well-being" OR "life satisfaction" OR “positive affect” OR “negative affect”)” AND “(child OR adolescent)" and their inter-terms in English, Portuguese and Spanish. As the integrative review on SWB (in the period 1970 and 2007) by Scorsolini-Comin and Santos (2010), had indicated a concentration of publications in 2005, it was decided to focus on publications from 2005 to 2016, in order to access studies that presented the recent interest in the scientific development of the theme of SWB.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria. This review included studies that met the following criteria: (1) published between 2005 and 2016; (2) articles in English, Portuguese or Spanish; (3) available in full in the databases; (4) contained the term "subjective well-being" in the title and/or keywords; (5) presented definition and measurement of SWB in the set of its components (LS, PA and NA), as defined by Diener (1984); and (6) performed with the general population of children and/or adolescents. Works that were excluded had the following criteria: (1) works other than articles, such as theses, monographs, dissertations, books and book chapters; (2) articles prior to the year 2005; (3) approach SWB only in a tangential way; (4) literature review articles; (5) performed with clinical population and other age groups (e.g., adults); (6) measured SWB with measurements corresponding to related variables (e.g., happiness); and (7) analyzed SWB limited to one of its dimensions, either LS or PA and/or NA.

Procedures. The initial search of the studies was performed through the uniterms and their combinations in the six bases selected. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to retrieved works. The complete articles were retrieved and cataloged in a spreadsheet in Excel for later analysis with a two-phase multimethod design, allowing for the broad analysis of the construct investigated. In the first stage, using a quantitative approach, an objective description of the profile of the publications was sought from eleven categories (Pires, Nunes, & Nunes, 2015): language of publication; geographic region in which the university of the first author is located; year of publication; design; analysis method; type of study; data collection material; instruments; number of participants; age of the participants (considering children to be from zero to eleven and adolescents from twelve to eighteen); and profile of participants. In the second stage, using a qualitative approach, the results were synthesized and interpreted with the identification of the themes based on the prominent trends found in the compilation of the selected studies. To do so, through content analysis (Bardin, 1977/1979), the next steps were followed: (a) the pre-analysis; (b) the exploration of the material; and, (c) treatment of results and interpretation. Thus, in an initial floating reading of the selected studies, hypotheses and indicators of analysis were identified. The data were then scanned and encoded from the units of registration based on the emerging central themes related to SWB. This was followed by verification of similarities and differences between the themes for further classification and grouping of the data into thematic axes. Afterwards, the data were presented and discussed based on the specific literature on SWB.

Results and Discussion

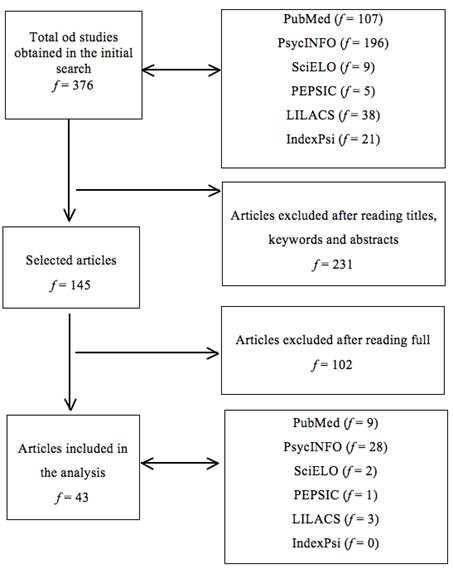

The initial search resulted in a total of 376 publications. After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria to the titles, keywords and abstracts and later after complete reading of the articles, 43 studies were selected, as shown in Figure 1.

Profile of the studies found and reasons for exclusion

In this section a description is presented of the reasons for exclusion of the studies found in the initial search and that were not included in the quantitative and qualitative analyzes because they did not meet the selection criteria. Of these studies, 104 publications examined SWB from other populations, these being different age groups (e.g., adults), clinical patients or patients with psychopathological symptomatology. The SWB of the adult population was investigated specifically in longitudinal studies that evaluated SWB as a measurement of psychosocial adjustment in adulthood and as an indicator of health in mothers of children with illnesses or developmental disorders.

Regarding the evaluation measurements, studies (f = 48) that used instruments which evaluated constructs related to SWB were excluded. These studies used scales of happiness, quality of life, perceived health, personality, self-esteem, self-efficacy, coping, social support, anxiety and depression. A consensus was found in regard to the diversity of definitions in the literature on SWB and that this construct is composed of the affective and cognitive dimensions. There were also studies that did not present a theoretical discussion about SWB, these were mainly studies in the area of health using the SWB nomenclature as a reference to measurements in quality of life and perceived health.

In regard to the theoretical perspective, studies (f = 25) that addressed three different conceptions of well-being were excluded. The most frequent was personal well-being (f = 17), followed by psychological well-being (f = 4) and well-being as a component of mental health (f = 4). These are conceptually close and are commonly used as synonyms of SWB. It is noted that the overlapping of expressions of well-being may be related to the theoretical and methodological discussions arising from the hedonic and eudaimonic paradigms and the bottom-up and top-down theories. In addition, there were those which did not present SWB in the title or keywords (f = 25), other languages (f = 11), theoretical studies (f = 4), errata of studies (f = 2), chapters and review (f = 12), dissertations and theses (f = 14), SWB evaluated only by affections (f = 6) or life satisfaction (f = 21) and SWB treated tangentially (f = 2).

Quantitative analysis of included studies

A predominance of publications in English (f = 38) was identified. Three studies were included in Portuguese and two in Spanish. The United States stood out with the largest number of publications (f = 13), followed by Brazil, Israel and China with five each, and Serbia with four publications. Next were Turkey with three publications and Mexico with two publications. Finland, Norway, Sweden, Spain, Malaysia and the Philippines had one publication each. This demonstrates an imbalance in the scientific production, warning that cultural differences need to be addressed in order to avoid a mistaken diffusion of theories and practices which come from a hegemonic context of populations not represented in the literature.

It was observed that there was an irregular increase in the number of productions over the years, with a significant increase in 2015 (f = 9) and 2012 (f = 9), followed by 2014 and 2013 with six publications in each year and 2011 with five publications. In the years 2016, 2009 and 2008, two publications were found in each year and in 2007 and 2005 one publication per year. No publications in the years 2010 and 2006 were found. The increase in SWB publications in the national and international contexts is consistent with previous studies in Positive Psychology, which reveal a rising trend in the study of subjective experience and positive personal characteristics (Reppold, Gurgel, & Schiavon, 2015).

There was a predominance of cross-sectional (f = 35) and quantitative (f = 39) studies. Only three studies were qualitative and one study was of mixed methods. Longitudinal studies evaluated SWB mainly as an indicator of satisfactory developmental outcomes. There is a definite need for elucidating longitudinal research on the possibilities of stability or variation in SWB over time.

Regarding the type of study, most (f = 34) identified correlations between SWB and negative aspects (e.g., domestic violence), positive aspects (e.g., coping) and socio-demographic variables (e.g., gender). In the correlation studies, there was a prevalence in those which explored the positive aspects, reflecting the variety of constructs and instruments developed in regard to positive emotions and characteristics, as well as the growing academic interest in positive functioning and personal growth. There were also studies that performed mediation (f = 3) and moderation (f = 3) analyzes. In addition, there were also studies that sought comparisons (f = 3), validation (f = 2) and construction (f = 1) of instruments.

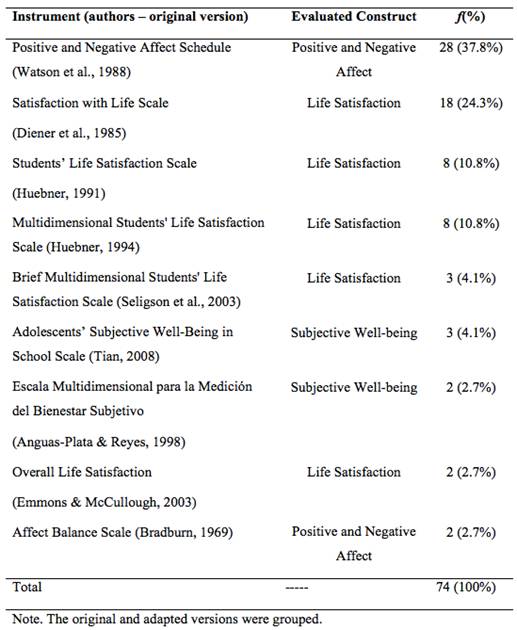

Studies that used pencil and paper instruments as data collection material were the most frequent (f = 39), followed by those which used the interview (f = 2), focal group (f = 1) and mixed (f = 1). In regard to the instruments, a variety of 22 were found (see Table 1). Such diversity reveals the concern of the researchers of the need to use instruments that consider the specificities of the age group and culture of the population investigated. For example, there are the instruments adapted for the Serbian (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-X - SIABPANAS; Novovi & Mihi, 2008) and adolescent population (Positive and Negative Affective Scale for Adolescents - EAPNA, Segabinazi et al., 2012). As shown in Table 1, most of the instruments were developed to measure life satisfaction. This finding is related to the complexity of the concept of life satisfaction which varies in the assessment of both life in an overall manner and its specific dimensions (family, school, etc.). However, seventeen publications used scales constructed in studies with the adult population without reporting adaptations to the infant/adolescent context, demonstrating that in these studies the measurement of SWB in children and adolescents may have been performed from the perspective of adults.

Table 1: Instruments Used to Evaluate Subjective Well-Being (Life Satisfaction, Positive Affect and Negative Affect)

The number of participants in the analyzed publications varied between 19 and 1476. More than 70% of the studies had from 1 to 500 participants and, as expected, the lowest sample quantity was found in the qualitative studies. The predominant age group was adolescents (f = 34), followed by mixed population (f = 5) and children (f = 4). The majority involved students from public and private urban schools (f = 40) and only three studies were carried out with non-normative population (organized and collected in social welfare institutions or in street situations). These results show the scenario of the publications about SWB, where the low number of studies with children and a non-normative population is revealed. It is noted that these population segments may require extra theoretical and methodological effort due to their nuances and specificities. However, research aimed at positive development and well-being must be attentive to the diversity of contexts and stages of the life cycle.

Qualitative analysis of included studies

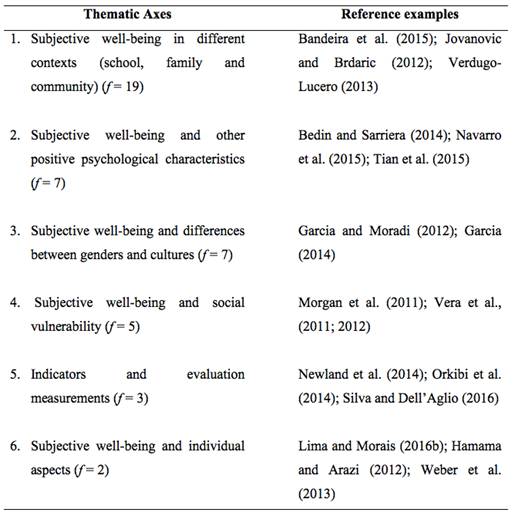

The qualitatively analyzed publications were classified into six thematic axes (see Table 2), in which the main themes and results addressed in the studies were highlighted, contributing to the findings related to the psychological evaluation, to the determinants of SWB, as well as to the relationship of SWB with the other positive psychological characteristics.

1. Subjective well-being in different contexts (school, family and community)

This study considers SWB as a multidimensional construct, which is influenced by contextual, social and cultural aspects. In the child/adolescent population, the school, family and community were the main ecological environments related to SWB.

In regard to the school context, the SWB favored positive academic results due to the influence of LS (e.g., Heffner & Antaramian, 2015). Students with a school curriculum with increased sports and arts activities were more satisfied with their lives (Orkibi, Ronen, & Assoulin, 2014). The social support of teachers and peers (eg, Tian, Zhao, & Huebner, 2015) and parental involvement (Yap & Baharudin, 2015) have beneficial effects on the self-efficacy of adolescents and these have, in turn, facilitated SWB. In addition, character strengths of temperance and transcendence (Shoshani & Slone, 2013), life purpose and clear objectives (Erylmaz, 2012) were indicators of SWB in school.

When considering the family context, adolescents with family satisfaction experience, on a global level, more LS and PA and less NA (Bernal, Arocena, & Ceballos, 2011). It can be emphasized that the relationship between adverse events and affections is not consensual. Some studies have pointed to more NA and less PA when there is exposure to domestic violence (Silva & Dell'Aglio, 2016), while others have not shown this influence, noting that self-control may favor higher levels of PA (Ronen, Hamama, & Rosenbaum, 2014). It is important to emphasize the investigation of interpersonal and contextual aspects in relation to SWB, since adolescents reported factors such as family conflict and death of a family member, among other adversities related to displeasurable emotions (Joronen & Åstedt-Kurki, 2005).

The studies express agreement on the relationship between SWB and ecological contexts, indicating that positive well-being is related to satisfactory experiences in the family, school and community and, longitudinally, at work (Newland et al., 2014). Schotanus-Dijkstra et al (2016) identified that higher levels of SWB were influenced by better living conditions and social support in family, friends and neighbors. It is noteworthy that in addition to satisfactory interpersonal relationships, the physical environment and access to sports and arts activities are indicators of the positive results of SWB, both globally and in specific domains. Therefore, there is a systemic approach, in which there seems to be a relationship of interdependence between LS and family satisfaction, among other significant contexts of development.

2. Subjective well-being and other positive psychological characteristics

The literature has shown interactions between SWB and other positive psychological variables (e.g., self-esteem, hope, optimism) (Borsa, Damásio, & Koller, 2016). In the population of children/adolescents, coping, optimism and creativity particularly stood out. A study on SWB and coping showed that in adolescents with high SWB index, the most used coping mechanism was acceptance of responsibility and the least frequently used was avoidance (Verdugo-Lucero et al., 2013). It is emphasized that the choice of coping mechanism used is important to understand the positive or negative impact on SWB. People may have higher levels of SWB while being guided and encouraged to use positive and efficient coping mechanisms (Zhou, Wu, & Lin, 2012).

In regard to optimism and SWB, the LS of the children was related to the optimism of the mothers (Bandeira, Natividade, & Giacomoni, 2015). This evidence enriches the discussion of positive attributes from a trans-generational point of view. Although there are no firm conclusions about the transmission from parents to children of SWB and optimism, the possibility of optimistic mothers working with positive parenting practices that imply pleasant experiences for the family members, which in turn favors SWB, is pointed out.

Looking at curiosity, positive relationships between curiosity, PA and LS (e.g., Jovanovic & Brdaric, 2012) were found. Although it is evident that curiosity does not directly contribute to positive emotional results, high levels of curiosity can promote SWB, but low levels of curiosity do not imply a greater experience of NA. This can occur due to low curiosity leading to avoidance of risky behavior, for example. The results that point to curiosity as a predictor of positive well-being corroborate the perspective that the PA and NA are independent.

In the relationship between gratitude and SWB, Froh, Yurkewicz, & Kashdan, (2009) refer to the strong relationship between gratitude and satisfaction in school, suggesting that the experience of gratitude seems to be an effective intervention to promote SWB. Future research should address specific outcomes related to SWB, gratitude, and academic performance (e.g., improvement in grades, increased attendance at school, and development and maintenance of positive peer relationships).

Thus, this indicates progress in the studies on SWB and other positive psychological characteristics. When analyzing the association between different positive correlates, there is progression in the proposition of effective strategies to raise the levels of well-being in the population. For example, by identifying the influence of personal goals on SWB, it is possible to delineate interventions to raise well-being levels by targeting, developing and strengthening personal goals and objectives (Steca et al., 2016).

3. Subjective well-being and differences between genders and cultures

Morgan et al. (2011) identified a reduced influence of predictive capacity in gender (between 4% and 6%) in NA levels. However, discussions about the relationship between SWB and gender do not concur, and thus do not allow for the confirmation of the importance of considering gender differences in SWB studies. For example, Vera et al. (2012) found that school satisfaction predicted LS in boys, while for girls, family satisfaction predicted LS. These differences may be related to gender stereotypes, in which boys are encouraged to enter extrafamilial spaces while girls are supposed to remain in the domestic space.

As for cultural differences in cultural minorities, studies (e.g., Vera et al., 2011) propose a bio-ecological perspective for understanding SWB, assessing individual and contextual aspects. In these studies, the importance of preventive programs that seek to promote SWB was highlighted. For these actions to take place, interventions were advised that articulate communication, relationships and coping, aiming at strengthening family cohesion and school support. Such strategies may help protect the individual against difficulties arising from the experience of living in different cultural conditions, protecting them from the possible negative effects of stressors and discrimination. These results show the relevance of research carried out on diverse populations, since the knowledge of the SWB indicators in different populations, which consider their singularities, can help advance programs directed to the promotion of skills and abilities that are personal and social, with a consequent positive impact on the SWB.

4. Subjective well-being and social vulnerability

Few studies have been found on the SWB of children/adolescents in socially vulnerable situations. In this study, some authors analyzed the SWB of young people living in war-threatened environments (e.g., Weber, Ruch, Littman-Ovadia, Lavy, & Gai, 2013), indicating personal and social resources as influential factors for SWB maintenance. Fear of war adversely affected SWB, while social support promoted SWB. In studies with young people in social welfare institutions, these adolescents reported more NA than those who lived with their families; however, the sample did not differ in relation to PA and LS (Poletto & Koller, 2011). Hamama and Arazi (2012) indicated that young members of families with low cohesion report low LS and high NA, which in turn precipitate aggressive behaviors. Results that were confirmed in later studies pointed to street children/adolescents experiencing more stressful events and worse adjustment indicators, with the exception of PA which did not differ from those living with their families ( Morais, Koller, and Raffaelli, 2012). However, it is important to consider the impact of situations of vulnerability on the health and well-being of children/adolescents. Zappe and Dell'Aglio (2016) found that institutionalized adolescents experience more intrafamily violence, have lower self-esteem and display more risky behavior than those who live with their families.

It is well known that adversities do not impede the SWB experience, as well as the fact that the promotion of a cohesive family environment is conducive to positive welfare assessments. It can be added that in the context of institutionalization, professionals and peers are important people with whom young people establish links that promote pleasant experiences (Lima & Morais, 2016b). The family is understood from an extended perspective that goes beyond consanguinity and is based on the quality and meaning of the ties. In this review, it is recommended to strengthen the positive relationships of the support network, be it the family, and/or the institution, among other expressive environments in the life of the children/adolescents.

5. Indicators and evaluation measurements

The identification of indicators and evaluation measurements has been of recurring interest in research with children/adolescents in the area of well-being, aiming to foster appropriate practices that promote quality of life. Navarro et al. (2015) sought to understand the concept of SWB and its influential factors from the perspective of children/adolescents by considering aspects that favor or impede the experience of well-being. It was pointed out that being healthy and having satisfying experiences with family, friends and school are important indicators of SWB, although it is necessary to consider differences between age, gender and sociocultural specificities. For example, what indicators would stand out in non-normative populations? What relationships established with people and environments of the support network would influence the SWB of this population? Should the school be referred to by children/adolescents who are not included in this context? Other studies have focused on improving SWB instruments for adolescents in the school context (Tian, Wang, and Huebner, 2015) and for specificities of the Brazilian population (Bedin & Sarriera, 2014).

These questions demonstrate the complexity surrounding SWB assessments. Considering life as a whole and its specific domains, in addition to differences between cultures that require transcultural validations, the literature presented reveals the expansion of the psychological evaluation in this field. Although there is a gap in other important micro-systems in the life of children/adolescents, such as those living in institutions or on the streets, for example. There is a need for a greater contextualization in the investigation of indicators and construction and validation of SWB instruments, with the aim to reach other networks of relationships and environments that are significant to the development of children and adolescents.

6. Subjective well-being and individual aspects

This axis is an expanding area, mainly regarding the investigations about the relationship between the personality factors and SWB (Noronha, Martins, Campos, & Mansão, 2015). In investigations of temperament (e.g., the search for new things), character (e.g., self-direction) and life events in relation to SWB, it was found that adolescents with high SWB recall more positive than negative events, indicating that they are predisposed to positivity. It was also pointed out that interventions focusing on the promotion of SWB should facilitate motivating experiences of self-acceptance, self-esteem, sense of purpose and value, sense of accomplishment and satisfactory interpersonal relationships (e.g., Garcia, 2014). It should be emphasized that the publications of this axis focused on the relationship of SWB with individual aspects without neglecting the influence of behavioral (temperament) and contextual factors (life events). This scenario corroborates with research which indicate an interactionist approach (between internal and external determinants) for a holistic understanding of SWB (Woyciekoski, Natividade, & Hutz, 2014).

Final considerations

The prevalence of international, empirical and cross-sectional publications of a quantitative nature, with adolescents, students from regular schools, can be identified. Even using a combination of search terms for the child and adolescent descriptors, a quartile of the publications dealt with the SWB of adults (which were excluded in the process of the selection of studies), with little representation of the population of children, especially from contexts of non-normative development.

There was observed an overlapping of terms of well-being, which, although having different conceptions, used SWB as a synonym. In order to clarify the specificities of the concepts investigated, there is the necessity to position the authors in regard to the paradigms that the investigations are based on, since depending on the theoretical contribution, the inquiries and explanations raised by the phenomena researched are different. For example, the hedonic paradigm considers emotions as components of well-being, while for the eudaimonic, emotions are products of psychological conditions (Ryan & Deci, 2001). These conceptions are complementary and contribute to a complex and holistic view of well-being. Yet, by focusing interests on different dimensions of well-being, there is a theoretical demarcation which aims to avoid undue conclusions in the understanding of scientific evidence.

The above considerations are increased for the methodological field, since the frequent use of evaluation measurements that address other positive psychological characteristics or even the use of negative moods (anxiety and depression) for SWB evaluation were found. Theoretical intersections regarding the positive functioning of people and those with whom they relate to may have contributed to this diversity of methodological compositions, as well as the misconceptions - for example, to measure SWB with a depression score. Thus, there is the need for methodological refinement, with the purpose of finding agreement between theory and method for adequate construction of the science of SWB in children and adolescents.

Although the interest is recent, it has been identified that scientific progress in the field of SWB has evidenced a combination of strategies to promote well-being, such as participating in religious activities, the meeting of basic needs and competences, relationships with others and autonomy, especially for those at school. The evidence from the studies emphasizes that the analysis of the relationship between SWB and other positive variables, as well as the simultaneous investigation of PA, NA and LS collaborate to identify factors that contribute to positive developmental outcomes. Thus, a bio-ecological model of well-being is observed, in which the relationships with the family, peers and professionals are evidenced, as well as the promotion of the individual characteristics (e.g., optimism) for SWB in children/adolescents. However, it is understood that there is a need to carry out further studies that address these issues, since there are many studies that evaluate SWB in only one of its components and there are different results, such as the relationship between curiosity and SWB.

Emphasis is given to the gap in knowledge regarding the population in social vulnerability. A small amount of the literature dealt with coping and overcoming strategies for the difficulties of these young people. In addition to this, we emphasize the need to investigate the common experience of feeling happy and satisfied with life. Longitudinal delineations can contribute to increasing knowledge of the developments of SWB, verifying its positive implications for development in the face of stressors and risks. Finally, it is indicated that the creation and evaluation of interventions with an emphasis on positive psychological characteristics in different contexts (including the family and institutions, among other significant environments for children/adolescents) is a fertile field for development in atypical contexts, deserving, therefore, further attention in future research.

This article has received financial support from CNPq nº 308659/2015, FUNCAP nº 15/2013 and CAPES nº 19/2016.

Referências

Bandeira, C. de M., Natividade, J. C., & Giacomoni, C. H. (2015). As relações de otimismo e bem-estar subjetivo entre pais e filhos.Psico-USF,20(2), 249-257. doi:10.1590/1413-82712015200206 [ Links ]

Baptista, M. N., Filho, N. H., & Cardoso, C. (2016). Depressão e bem-estar subjetivo em crianças e adolescentes: Teste de modelos teóricos. Psico, 47(4), 259-267. doi: 10.15448/1980-8623.2016.4.23012 [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (1979). Análise de Conteúdo. (L. Reto & A. Pinheiro, Trad.). São Paulo: Edições 70, Livraria Martins Fontes. ( Originalmente publicado em 1977). [ Links ]

Bedin, L. M., & Sarriera, J. C. (2014). Propriedades psicométricas das escalas de bem-estar: PWI, SWLS, BMSLSS e CAS. Avaliação Psicológica ,13(2), 213-225. [ Links ]

Bernal, A. C. A. L., Arocena, F. A. L., & Ceballos, J. C. M. (2011). Bienestar subjetivo y satisfacción con la vida de familia en adolescentes mexicanos de Bachillerato. Psicología Iberoamericana, 19(2), 17-26. [ Links ]

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Koller, S. H. (2016). Escala de Positividade (EP): Novas evidências de validade no contexto brasileiro. Psico -USF , 21(1), 1-12. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712016210101 [ Links ]

Casas, F. (2015). Analyzing the Comparability of 3 Multi-Item Subjective Well-Being Psychometric Scales Among 15 Countries Using Samples of 10 and 12-Year-Olds. Child Indicators Research, 10(2), 297-330. doi: 10.1007/s12187-015-9360-0 [ Links ]

Casas, F., Fernández-Artamendi, S., Montserrat, C., Bravo, A., Bertrán, I., & Dell Valle, J. F. (2013). El bienestar subjetivo en la adolescencia: estudio comparativo de dos Comunidades Autónomas en España.Anales de Psicología , 29(1), 148-158. doi:10.6018/analesps.29.1.145281 [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., & Zolowski, A. P. C. (2014). Como escrever um artigo de revisão sistemática. In S. H. Koller, M. C. P. P. Couto, & J. Von Hohendorff (Eds.),Manual de Produção Científica (55-70). Porto Alegre: Penso Editora. [ Links ]

Cummins, R. A. (2010). Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 1-17. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9167-0 [ Links ]

Damásio, F., Zanon, C., & Koller, S. (2014). Validation and psychometric properties of the brazilian version of the subjective happiness scale. Universitas Psychologica, 13(1), 17-24. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-1.vppb [ Links ]

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Human Behavior, 2, 253-260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6 [ Links ]

Disabato, D. J.; Goodman, F. R.; Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L., & Jarden, A. (2016). Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 471-482. doi: 10.1037/pas0000209 [ Links ]

Erylmaz, A. (2012). A model of subjective well-being for adolescents in high school. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 275-289. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9263-9 [ Links ]

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T.B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence , 32(3), 633-50. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006 [ Links ]

Garcia, D. (2014). La vie en rose: high levels of well-being and events inside and outside autobiographical memory. Journal of Happiness Studies , 15(3), 657-672. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9443-x [ Links ]

Hamama, L., & Arazi, Y. (2012). Aggressive behaviour in at-risk children: Contribution of subjective well-being and family cohesion. Child & Family Social Work, 17, 284-295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00779.x [ Links ]

Heffner, A. L., & Antaramian, S. P. (2015). The role of life satisfaction in predicting student engagement and achievement. J Happiness Stud, 1-21. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9665-1 [ Links ]

Joronen, K., & Astedt-Kurki, P. (2005). Familial contribution to adolescent subjective well-being. International Journal of Nursing Practice,11(3), 125-33. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00509.x [ Links ]

Jovanovic, V., & Brdaric, D. (2012). Did curiosity kill the cat?Evidence from subjective well-being in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 380-384. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.043 [ Links ]

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61, 121-140. doi: 10.2307/2787065 [ Links ]

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207-222. doi: 10.2307/3090197 [ Links ]

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., ... Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 65-94. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700 [ Links ]

Lee, B. J., & Yoo, M. S. (2015). Family, School, and Community Correlates of Children’s Subjective Well-being: An International Comparative Study. Child Ind Res, 8(1), 151-175. doi: 10.1007/s12187-014-9285-z [ Links ]

Lima, R. F. F., & Morais, N. A. (2016a). Fatores associados ao bem-estar subjetivo de crianças e adolescentes em situação de rua. Psico (Porto Alegre), 47(1), 24-34. doi:10.15448/1980-8623.2016.1.20011 [ Links ]

Lima, R. F. F., & Morais, N. A. (2016b). Caracterização qualitativa do bem-estar subjetivo de crianças e adolescentes em situação de rua. Temas em Psicologia, 24(1), 1-15. doi:10.9788/TP2016.1-01 [ Links ]

Luhmann, M., Hofmann, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 102(3), 592-615. doi:10.1037/a0025948 [ Links ]

Morais, N. A., Koller, S. H., & Raffaelli, M. (2012). Rede de apoio, eventos estressores e mau ajustamento na vida de crianças e adolescentes em situação de vulnerabilidade social. Universitas Psychologica , 11(3), 779-791. doi: 10.11144/779 [ Links ]

Morgan, M. L., Vera, E. M., Gonzales, R. R., Conner, W., Vacek, K. B., & Coyle, L. D. (2011). Subjective well-being in urban adolescents: Interpersonal, individual, and community influences. Youth Society, 43(2), 609-634. doi:10.1177/0044118X09353517 [ Links ]

Navarro, D., Montserrat, C., Malo, S., González, M., Casas, F. and Crous, G. (2015), Subjective well-being: What do adolescents say? Child & Family Social Work . doi:10.1111/cfs.12215 [ Links ]

Newland, L. A., Giger, J. T., Lawler, M. J., Carr, E. R., Dykstra, E. A., & Roh, S. (2014). Subjective well-being for children in a rural community. Journal of Social Service Research , 40(5), 642-661. doi:10.1080/01488376.2014.917450 [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., Martins, D. da F., Campos, R. R. F., & Mansão, C. S. M. (2015). Relações entre afetos positivos e negativos e os cinco fatores de personalidade.Estudos de Psicologia, 20(2), 92-101. doi:10.5935/1678-4669.20150011 [ Links ]

Orkibi, H., Ronen, T., & Assoulin, N. (2014). The subjective well-being of israeli adolescents attending specialized school classes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(2), 515-526. doi:10.1037/a0035428 [ Links ]

Pires, J. G., Nunes, M. F. O., & Nunes, C. H. S. da S. (2015). Instrumentos baseados em Psicologia Positiva no Brasil: Uma revisão sistemática. Psico -USF , 20(2), 287-295. doi:10.1590/1413-82712015200209 [ Links ]

Poletto, M., & Koller, S. H. (2011). Subjective well-being in socially vulnerable children and adolescents. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica,24(3), 476-484. doi:10.1590/S0102-79722011000300008 [ Links ]

Pompeu, D. A., Rossi, L. A., Galvão, C. M. (2009). Revisão integrativa: Etapa inicial do processo de validação de diagnóstico de enfermagem. Acta Paul. enferm., 22(4), 434-438. doi:10.1590/s0103-21002009000400014 [ Links ]

Pureza,J. R., Kuhn, C. H. C., Castro,E. K., & Lisboa, C. S. M. (2012). Psicologia positiva no Brasil: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. doi:10.5935/1808-5687.20120016 [ Links ]

Reppold, C. T., Gurgel, L. G., & Schiavon, C. C. (2015). Research in positive psychology: A systematic literature review. Psico -USF, 20(2), 275-285. doi:10.1590/1413-82712015200208 [ Links ]

Ronen, T., Hamama, L., & Rosenbaum, M. (2014). Subjective well-being in adolescence: The role of self-control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies ,17(1), 1-24. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9585-5 [ Links ]

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Reviews Psychology, 52, 141-166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 [ Links ]

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happinnes is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Jornal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [ Links ]

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H. C., Westerhof, G. J., Graaf, R., ten Have, M., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of Happiness Studies , 17,1351-1370. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9647-3 [ Links ]

Scorsolini-Comin, F., & Santos, M. A. (2010). O estudo científico da felicidade e a promoção da saúde: Revisão integrativa da literatura. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 18(3), 187-195. [ Links ]

Segabinazi, J. D., Zortea, Ma., Zanon, C., Bandeira, D. R., Giacomoni, C. H., & Hutz, C. S. (2012). Escala de afetos positivos e negativos para adolescentes: Adaptação, normatização e evidências de validade.Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem Avaliação Psicológica,11(1), 1-12. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psycology: an introduction. American Psychological Association, 55(1), 5-14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 [ Links ]

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2013). Middle school transition from the strengths perspective: Young adolescents’ character strengths, subjective well-being, and school adjustment. J Happiness Stu, 14(4), 1163-1181. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9374-y [ Links ]

Silva, D. G., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2016). Exposure to Domestic and Community Violence and Subjective Well-Being in Adolescents. Paidéia, 26(65), 299-305. doi:10.1590/1982-43272665201603 [ Links ]

Steca, P., Monzani, D., Greco, A., D’Addario, M., Cappelletti, E., & Pancani, L. (2016). The effects of short-term personal goals on subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies , 17, 1435-1450.doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9651-7 [ Links ]

Tian, L., Wang, D., & Huebner, S. (2015). Development and validation of the brief adolescents’ subjective well-being in school scale (BASWBSS). Social Indicators Research , 120(2), 615-634. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0603-0 [ Links ]

Tian, L., Zhao, J., & Huebner, E. S. (2015). School-related social support and subjective well-being in school among adolescents: The role of self-system factors. J Adolesc ., 45, 138-48. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.003 [ Links ]

Vera, E. M., Moallem, B. I., Vacek, K. R., Blackmon, S., Coyle, L. D., Gomez, K. L., & Steele, J. C. (2012). Gender differences in contextual predictors of urban, early adolescents' subjective well-being. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development, 40, 174-183. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2012.00016.x [ Links ]

Vera, E. M.., Vacek, K., Coyle, L. D., Stinson, J., Mull, M., Doud, K., … Langrehr, K. J. (2011). An examination of culturally relevant stressors, coping, ethnic identity, and subjective well-Being in urban, ethnic minority adolescents. Professional School Counseling, 15(2), 55-66. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2011-15.55 [ Links ]

Verdugo-Lucero, J. L., Ponce de León-Pagaza, B. G., Guardado-Llamas, R. E., Meda-Lara, R. M., Uribe-Alvarado, J. I., & Guzmán-Muñiz, J. (2013). Estilos de afrontamiento al estrés y bienestar subjetivo en adolescentes y jóvenes. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 11(1), 79-91. doi:10.11600/1692715x.1114120312 [ Links ]

Weber, M., Ruch, W., Littman-Ovadia, H., Lavy, S., & Gai, O. (2013). Relationships among higher-order strengths factors, subjective well-being, and general self-efficacy - the case of Israeli adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences , 55(3), 322-327. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.006 [ Links ]

Woyciekoski, C., Natividade, J. C., & Hutz, C. S. (2014). As contribuições da personalidade e dos eventos de vida para o bem-estar subjetivo. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 30(4), 401-409. doi: 10.1590/s0102-37722014000400005 [ Links ]

Yap, S. T., & Baharudin, R. (2015). The relationship between adolescents’ perceived parental involvement, self-efficacy beliefs, and subjective well-being: A multiple mediator model. Soc Indic Res. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-0882-0 [ Links ]

Zappe, J. G., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2016). Risco e proteção no desenvolvimento de adolescentes que vivem em diferentes contextos: Família e institucionalização. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 25(2), 289-305. doi: 10.15446/rcp.v25n2.51256 [ Links ]

Zhou, T., Wu, D., & Lin, L. (2012). On the intermediary function of coping styles: Between self-concept and subjective well-being of adolescents of Han, Qiang and Yi nationalities. Psychology, 3(2), 136-142. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.32021 [ Links ]

Received: September 01, 2017; Revised: March 20, 2018; Accepted: August 27, 2018

text in

text in