Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.12 no.2 Montevideo nov. 2018

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1681

Original Articles

Relationships between character strengths and perception of social support

1Programa de Pós-graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco. Brasil ana.noronha8@gmail.com,elainenogueira.psi@gmail.com, fabian.rueda@usf.edu.br Correspondence: Ana Paula Porto Noronha. Rua Waldemar Cesar da Silveira, 105, Jardim Cura D´ars. Campinas - SP - Brasil

Keywords: positive psychology; psychological assessment; social support; strengths; adolescence

Palabras clave: psicología positiva; evaluación psicológica; apoyo social; fortalezas; adolescencia

Palavras-chave: psicologia positiva; avaliação psicológica; suporte social; forças; adolescência

Introduction

Character strengths are relatively stable, pro-social characteristics that can be manifested through behaviors, thoughts, or feelings. They must be authentic to the individual and allow a functioning close to his or her ideal (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The authors elaborated a classification (Niemiec, 2013), resulting from an extensive literature review, titled Values In Action (VIA), which brings together 24 strengths distributed among six virtues, in order to clearly describe human potentialities.

Two instruments were developed based on VIA suppositions: the Values In Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) and the Values In Action Youth Survey (VIA-Y). Both scales are aimed at assessing individual differences in people’s qualities (Snyder & Lopez, 2009). The instrument was translated into several languages, which generated much research, some with recent publications (McGrath, 2015a, McGrath, 2015b, Proyer, Gander, Wellenzohn, & Ruch, 2015; Ruch, Martínez-Martí, Proyer, & Harzen, 2014a, Ruch, Weber, Park, & Peterson, 2014b, Shoshani & Slone, 2013, among others). There is a Portuguese translation and a study with a Brazilian sample was published with the objective of performing a cross-cultural adaptation, investigating the internal structure, and obtaining demographic data (Seibel, DeSouza, & Koller, 2015).

Moreover, in Brazil, Noronha and Barbosa (2016) constructed a Character Strengths Scale, using the VIA model and applying it to Brazilian samples. In this context, the present work proposes to seek relationships between character strengths and perceived social support (American Education Research Association, American Psychology Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education - AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014 Urbina , 2007). The relationship with other variables was chosen for this research, which sought correlation patterns between the test scores and other variables that measure the same construct or related constructs and with variables that measure different constructs (American Education Research Association, American Psychology Association & National Council on Measurement in Education - AERA, APA & NCME, 2014).

Character strengths and social support will be correlated, through the respective instruments, and the theoretical justification is based on the understanding that the environment exerts influence in the strengthening of emotions and character strengths, that being in a promising and safe social environment, in which there is the incentive of potential, it is likely that individuals have more resources to improve their skills (Snyder & Lopez, 2009). For the authors, children and adolescents living in social contexts in which the negative aspects are pronounced do not develop coping resources and, seeking solutions to their problems, face life with little enthusiasm. The statement by Campos (2004) follows the same reasoning: the extent to which the individual perceives this support and finds the strength to face adverse situations, results in positive consequences for his/her well-being, such as reduced stress, increased self-esteem and psychological well-being.

According to Cobb (1976), social support refers to the support received by members of the individual’s social environment-i.e. friends, classmates, work colleagues and community), though it can also be offered by family. Supportive relationships can be considered a positive factor in individuals’ development, given the need for interrelationship and satisfaction that the giving or receiving process helps trigger, as well as the impact on self-esteem (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, 2008).

Still in order to define the construct, Cobb (1976) stated that social support is related to the beliefs of being loved, being appreciated for his/her value, and, finally, to the perception that people care about him/her. Thois (1982), in turn, postulated that the social support construct presents a so-called instrumental dimension, beyond the affective dimension mentioned above, in which the individual realizes that people can help him/her through financial and practical resources such as, for example, lending money, taking care of a child for a few hours, or even giving a ride to the doctor when needed. Rodriguez and Cohen (1998) stated that one more dimension should be included in social support, namely informational support, which refers to the possibility of receiving information from others that helps the individual in the problem-solving and decision-making processes.

Positive psychology interventions aimed at youth have been necessary, to ensure the positive development of young people. There is ample evidence for its effectiveness in increasing well-being, improving depression (Proyer, Gander, Wellenzohn, & Ruch, 2015), and increasing academic performance (Weber & Rusch, 2012). However, the authors prioritize the determination of individuals’ principal strengths (Proyer et al., 2015), and not on their relation to other constructs, which affirms the importance of the present study. Bastianello and Hutz (2016) endorse claims that research on issues related to character strengths, emotions, and positive attachments, such as optimism and social support, appear to be poorly addressed.

Among the themes investigated are those designed for the construction and validation of instruments, such as the present work, and those designed for intervention (Renshaw & Steeves, 2016).

Although studies with the VIA instruments are becoming current (Toner, Haslam, Robinson, & Williams, 2012), their relation with other constructs is still incipient. Highlighting the research of Shoshani and Slone (2013), in a longitudinal study, the authors' goal was to examine the associations between character strengths, subjective well-being, school performance of adolescents, and social behavior during the transition to high school in public schools. The results identified, especially in relation to social behavior, that the strengths of kindness, love, and gratitude predict social adjustment and can improve the ability of adolescents to maintain and establish interpersonal relationships and develop social identities and a sense of belonging.

Regarding the relationship between subjective well-being, Gratitude, Hope/Optimism, Love, and Vitality strongly correlated with life satisfaction in the research of Ruch, et al. (2014a). Accordingly, Ruch et al. (2014b), in developing research to adapt VIA-Youth to a German population, found the same strengths as those most related to life satisfaction.

Using the Character Strengths Scale in Brazil, Noronha and Martins (2016) found a relationship between Vitality, Gratitude, Hope/Optimism, Perseverance, and Love with life satisfaction in moderate magnitudes. In a similar study, Oliveira, Nunes, Legal and Noronha (2016) found relationships between subjective well-being and the same previous strengths, plus Humor and Love of learning. The present research aimed to relate the results of the Character Strengths Scale (EFC) to those related to the Social Support Scale (EPSUS-IJ).

Method

Participants

A total of 293 adolescents participated in the study, age 14 to 17 years (M = 14.95, SD = 3.038), 67.8% female and 32.2% male. The participants were junior high and high school students in the 8th (n = 9), 9th (n = 9), 10th (n = 85), 11th (n = 150) and 12th (n = 40) grades. With regard to parental marital status, 53.6% of the adolescents had parents that were married. The convenience sample was from five public schools in state of São Paulo.

Instruments

Two instruments were used to meet the study’s objectives. First, the Character Strengths Scale (EFC, Noronha & Barbosa, 2016) was developed based on the Values In Action model and is intended to evaluate 24 character strengths. A 72-item construction was submitted to a review panel for analysis and for the pilot study. One item was suppressed and, for the validity studies, a second order analysis was performed, with the 24 character strengths, to investigate the dimensionality of the instrument. To determine the number of factors that should be extracted, Noronha, Dellazzana-Zanon and Zanon (2015) used different methods of analysis in determining that the theoretical model of virtues could not be replicated. The alpha coefficient (0.93) indicated high reliability.

The Perceived Social Support Scale-Child-Adolescent Version (EPSUS-IJ) was the second instrument used, developed by Baptista and Cardoso (2013) and based on the assumptions of Rodriguez and Cohen (1998). The scale’s objective is to evaluate children’s and adolescents’ perceptions of support received in the social context, that is, to evaluate how they perceive their social relationships in affective aspects, social interaction, and coping with problems. The scale is composed of 23 items, distributed among three factors, such as: Coping with Problems (11 items, with α = 0.91), related to the respondent’s perception of peer support in moments of decision-making; Social Interaction (five items, with α = 0.88), which evaluates the quality of subjects' relationships with others; and Affectivity (seven items, with α = 0.91), related to emotional support.

Procedures

The project was first submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Francisco and, after approval (CAAE 36085814.6.0000.5514), the school board for a town in São Paulo state was contacted, as well as the institutions, to gain authorization for data collection. After receiving Board approval, and approval by the schools, a secondary contact was made with the schools to schedule the applications.

Because the survey participants were under 18 years of age, all research information, guidelines and collection procedures were provided to the guardians via the students, and Free and Informed Consent forms (FIC) were signed. After the FICs were collected, students were shown to a separate room where they responded to the instruments. With regard to the instrument sequence, the EFC was administered first followed by the EPSUS-IJ. The instruments were applied collectively, within a duration of approximately 45 minutes.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software version 22.0, linear regression in particular. For this, enter was the chosen method, considering each of the 24 character strengths as a dependent variable and the five personality traits as independent variables. This analysis was used to meet the objective of the study (Hair, Tatham, & Black, 2005).

Results

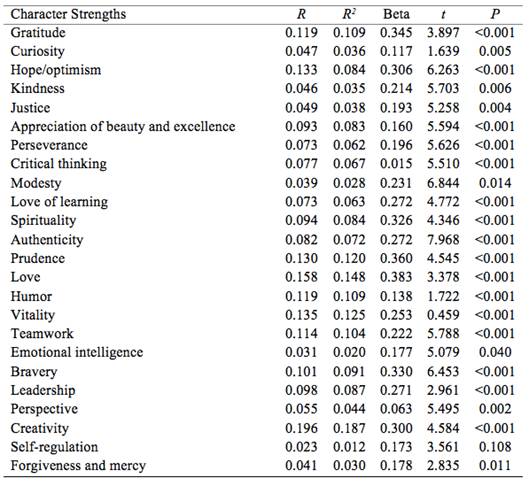

Prior to the aforementioned linear regression analysis, predictive character strengths analyses were performed, individually, based on the Perceived Social Support Scale factors. For each of the 24 regressions, Coping with Problems (Factor 1), Social Interaction (Factor 2) and Affectivity (Factor 3) were selected as independent variables. Table 1 shows the regression coefficients summarized.

Of the 24 regressions, with the exception of Self-regulation, the 23 others were significant. Of these, the adjusted coefficients of determination (R 2 ) varied from 0.020 (Emotional Intelligence) to 0.187 (Creativity). Accordingly, we can say that 7 strengths were better predicted, namely Gratitude, Prudence, Love, Humor, Vitality, Teamwork and Creativity. Continuing in this line, perceived social support represented 19% of the explained variance of the strength Creativity, 15% of Love and 13% of Vitality. In order to better understand the contribution of EPSUS-IJ factors toward the explanation of character strengths, Table 2 informs on the significance of each.

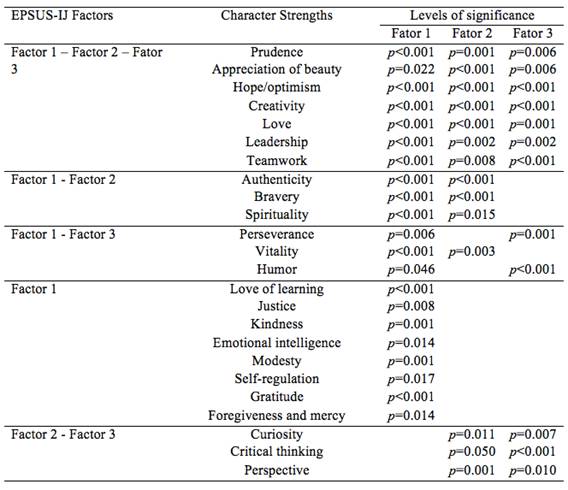

Table 2: Levels of significance relative to the contribution of each factor of EPSUS-IJ to explain character strengths

The data allow us to identify that Factor 1 (Coping with Problems) contributed significantly in 21 strengths. Social Interaction, Factor 2, presented significant coefficients in 14 strengths, and Affectivity (or Factor 3), in 12 strengths. A discussion of these findings follows.

Discussion

According to McGrath (2015a), one reason that studies directed at the character strengths, such as the present research, are relevant is because such strengths are subject to lexical differences as well as cultural context, even while they are recognized as universal human characteristics. From this perspective, studying the model with distinct samples is necessary. Added to this is the fact that validity evidence is sought for a character strengths assessment instrument whose construction and validation of measures is still urgent (Aens, APA, & NCME, 2014; Renshaw & Steeves, 2016).

Favorable perceived social support plays a protective role in the face of the difficulties encountered by adolescents (Thompson, Mazza, Herting, Randell, & Eggert, 2005), and may reduce negative effects on health (Nurullah, 2012). Because of this, it was elected as a construct to be related to the Character Strengths Scale. For Procidano and Hellen (1983), the study of perceived social support in adolescents may reveal important information since, depending on the nature of established peer relationships, changes are observed throughout their development, which negatively or positively impact perceived social support.

Regarding the findings, perceived social support-that is, how much the participants in the sample perceive that their social relationships have affective aspects and help to face problems-predicted with greater prominence seven strengths. Three strengths (1) Love (values relationships with others, in which there is reciprocal exchange and affection, and prioritizes to closeness with them), (2) Teamwork (works well within a group, collaborates and is loyal) and (3) Humor (makes people laugh and systematically values positive aspects of situations) are very focused on contact with the Other, which justifies the results. Similarly, Gratitude (being aware that good things happen) also favors the relationship between life events and people.

By another measure, the strengths of Creativity (trying to do things differently), Vitality (living with enthusiasm and energy), and Prudence (being cautious in one’s decisions so as not to take undue risks) seem to be necessary to the establishment of favorable relationships. As highlighted by Snyder and Lopez (2009), if the social context lacks positive role models and affection, young people will have fewer resources to face life with enthusiasm and solve their problems. In the same direction, the authors endorse that environment exerts great influence in the forging of character strengths. From this perspective, a promising and safe environment tends to stimulate the development of potentialities, so that the individual tends to present more resources for perfecting his/her skills.

Ruch et al. (2014a) developed research aiming to adapting the VIA-Youth to the German population. Their results partially corroborate those of the present study, since the character strengths of Hope, Gratitude, Love and Vitality correlated positively with life satisfaction. In relation to social behavior, Shoshani and Slone (2013) have shown that interpersonal strengths (among them, Kindness, Love and Gratitude) are predictors of social adjustment and, in addition, can improve the adolescent’s ability to establish and maintain interpersonal relations, and to develop social identities and a sense of belonging, which reaffirm part of the results obtained here. The authors endorse that social support, feeling of belonging to the group, is associated with psychological well-being.

As for the best predictor, Factor 1 of the Perceived Social Support Scale, respondents most frequently related their perception of how much support was received from their social network members in moments of decision-making. This is pertinent given the assertions of Bastianello and Hutz (2016), that people who perceive strong social support present better emotional adjustment. Finally, character strengths can be fortified and programs that aim to broaden them have achieved satisfactory effects (Proyer, Gander, Wellenzohn, & Ruch, 2015; Wagner & Ruch, 2015).

Final considerations

The first objective of the research was satisfied. Findings indicated that perceived social support, most strongly the EPSUS-IJ Factor 1 that evaluates perceived support from one’s social network in moments of decision making, is related to character strengths.

The strengths are understood as protective factors for the adolescents and, to some extent, taking as a reference the concept of character strengths, that is, pre-existent capacity for a particular form of behavior, thought and feeling, that present themselves in an authentic way to the individual, his/her relation with the coping with problems, and affectivity reaffirms the characteristic of the strengths’ protective factor, as pointed out by Peterson and Seligman (2004). In addition, social support refers to a complex and multifaceted construct, which brings together different dimensions of the subject's life, and translates the individual's perception of the environment and his/her relationships (Baptista, Baptista, & Torres, 2006).

This investigation can aid in the social understanding of the emotional, familiar and social phenomena of the subjects. That said, all scientific investigation of human potentialities that may contribute to the development of psychological knowledge, becomes relevant.

A limitation of the study refers to the sample, which is primarily represented by public school youth from a town in the São Paulo countryside. Therefore, as a research agenda, we see the need to broaden the analyzed variables and rely on a more representative sample. Verifying relationships between the adolescents and their parents (guardians) could also suggest other important reflections.

Referencias

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education - AERA, APA, & NCME (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. New York: American Educational Research Association. [ Links ]

Baptista, M. N., & Cardoso, H. F. (2013). Escala de Percepção do Suporte Social (Versão Infanto-Juvenil): relatório técnico não publicado. Universidade São Francisco: Itatiba. [ Links ]

Bastianello, M. R., & Hutz, C. S. (2016). Otimismo e suporte social em mulheres com câncer de mama: uma revisão sistemática.Psicologia: teoria e prática,18(2), 19-33. doi: 10.15348/1980-6906/PSICOLOGIA.V18N2P19-33. [ Links ]

Campos, E. P. (2004). Suporte Social e Família. En: J. Mello Filho (Org.), Doença e família (pp. 141-161). São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38(5), 300-314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [ Links ]

De Jong Gieverld, J., & Dykstra, P. A. (2008). Virtue is its own reward? Support-giving in the family and loneliness in middle and old age. Ageing and Society, 28(2), 271-287. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X07006629. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., & Black, C., (2005). Análise Multivariada de Dados. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [ Links ]

McGrath, R. E. (2015a). Measurement Invariance in Translations of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 1, 1-8. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000248. [ Links ]

McGrath, R. E. (2015b). Integrating psychological and cultural perspectives on virtue: The hierarchical structure of character strengths. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 407-424. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.994222. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Barbosa, A. J. G. (2016). Escala de Forças e Virtudes. En C.Hutz (Org.), Avaliação em Psicologia Positiva (pp. 42-53). São Paulo: Hogrefe. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L., & Zanon, C. (2015). Internal Structure of the Strengths and Virtues Scale in Brazil. Psico-USF, 20(2), 229-235. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200204. [ Links ]

Noronha, A. P. P., & Martins, D. F. (2016). Associações entre forças de caráter e satisfação com a vida: estudo com universitários. Acta Colombiana de Psicologia, 19(2), 83-89. [ Links ]

Nurullah, A. S. (2012). Received and provided social support: a review of current evidence and future directions.American Journal of Health Studies, 27(3), 173-188. [ Links ]

Oliveira, C., Nunes, M. F. O., Legal., E., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2016). Subjective Well-Being: Linear Relationships to Character Strengths. Avaliação Psicológica, 15(3), 177-185. [ Links ]

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E.P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Procidano, M. E., & Heller, K. (1983). Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11(1), 1-24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [ Links ]

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2015). Strengths-based positive psychology interventions: A randomized placebo-controlled online trial on long-term effects for a signature strengths- vs. a lesser strengths-intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(456), 1-14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00456. [ Links ]

Renshaw, T., & Steeves, R. M. O. (2016). What good is gratitude in youth and schools? A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates and intervention outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 286-305. doi: 10.1002/pits.21903. [ Links ]

Rodriguez, M., & Cohen, S. (1998). Social support. En: H. Friedman(Org.), Encyclopedia of Mental Health (pp. 535-544). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Ruch, W., Martínez-Martí, M. L., Proyer, R. T., & Harzen, C. (2014). The Characters Strengths Rating Form (CSRF): Development and initial assessment of a 24-item rating scale to assess character strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 53-58. [ Links ]

Ruch, W., Weber, M., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2014). Character strengths in children and adolescents: Reliability and initial validity of the German Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth (German VIA-Youth). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30(1), 57-64. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000169. [ Links ]

Seibel, B. L., DeSouza, D., & Koller, S. H. (2015). Adaptação Brasileira e Estrutura Fatorial da Escala 240-item VIA Inventory of Strengths. Psico-USF, 20(3), 371-383. doi: 10.1590/1413-82712015200301. [ Links ]

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2013). Middle School Transition from the Strengths Perspective: Young adolescents´ Character Strengths, Subjective Well-Being and School Adjustment. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1163-1181. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9374-y. [ Links ]

Snyder, S. J., & Lopez, C. R. (2009). Psicologia Positiva: uma abordagem científica e prática das qualidades humanas. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Thompson, E. A., Mazza, J. J., Herting, J. R., Randell, P. B., & Eggert, L. L. (2005). The mediating roles of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness on adolescent suicidal behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behavior, 35(1), 14-34. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.1.14.59266. [ Links ]

Toner, E., Haslam, N., Robinson, J., & Williams, P. (2012). Character strengths and wellbeing in adolescence: Structure and correlates of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Children. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 637-642. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.014. [ Links ]

Urbina, S. (2007). Fundamentos da testagem psicológica. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Wagner, L., & Ruch, W. (2015). Good character at school: Positive classroom behavior mediates the link between character strengths and school achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(610), 1-13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00610. [ Links ]

Weber, W., & Ruch, W. (2012). The role of a good character in 12-year-old school children: Do character strengths matter in the classroom? Child Indicators Research, 5, 317-334. doi: 10.1007/s12187-011-9128-0. [ Links ]

Received: October 09, 2017; Revised: May 29, 2018; Accepted: July 31, 2018

texto en

texto en