Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.11 no.2 Montevideo nov. 2017

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v11i2.1500

Original Articles

Teachers`attitudes towards inclusive education

1Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Católica del Uruguaymarialeticiaang@gmail.com

2Facultad de Psicología - Universidad Católica del Uruguay Correspondencia: Ignacio Navarrete Antola. Depto. de Psicología del Desarrollo y Educacional.. Comandante Braga 2715. C.P 11600. Montevideo inavarre@ucu.edu.uy

Abstract: The first aim of this study is to describe the attitudes of preschool and elementary school teachers from a private school in Montevideo towards inclusive education. Attitude is defined as a set of perceptions, beliefs, positive and negative feelings, and ways of reacting to an educational process in which the main focus is for all learners to achieve learning outcomes. The second aim is to analyze whether these attitudes depend on a teacher’s position, academic background, contact with people with disabilities, educational stage, and years of professional experience. The study had a cross-sectional, descriptive design and utilized the Inclusive Education Opinion Scale instrument. Attitudes were assessed using a 23-item instrument with five response levels on a Likert-type Attitude Scale. The study worked with a non-probability sample of 44 English and Spanish teachers. The results demonstrated positive attitudes towards the foundations of inclusive education and towards inclusive practices. Additionally, the results reflect that Spanish language teachers have more positive attitudes towards the foundations of inclusive education compared to their English language colleagues. Furthermore, more experienced teachers were found to have more positive attitudes towards inclusive measures and practices. No statistically significant differences were found between teachers’ attitudes and the educational stage taught

Key Words: Inclusion; attitudes; inclusive education; preschool and elementary education

Resumen: Este estudio tiene como primer objetivo describir las actitudes de los docentes de enseñanza inicial y primaria en un colegio privado de Montevideo sobre la educación inclusiva. Entendiendo como actitud, un conjunto de percepciones, creencias, sentimientos a favor o en contra y formas de actuar ante el hecho educativo que centra su esfuerzo en el logro de los aprendizajes. Un segundo objetivo es analizar si dichas actitudes dependen del cargo como docente, la formación académica, el contacto con personas con discapacidad, la etapa educativa y los años de experiencia profesional. El diseño fue de tipo transversal y descriptivo y el instrumento utilizado, la Escala de Opinión acerca de la Educación Inclusiva. Las actitudes se valoraron a través de un instrumento de 23 ítems, con cinco alternativas de respuesta en la Escala de Actitudes tipo Likert. Se trabajó con una muestra no probabilística de 44 docentes de inglés y español. Los resultados mostraron una actitud favorable hacia los fundamentos de la educación inclusiva y hacia las prácticas inclusivas. Asimismo, reflejan que los docentes de español tienen una actitud más favorable que sus pares de inglés con respecto a los fundamentos de la educación inclusiva. Además, se encontró que los docentes con más experiencia tienen una actitud más favorable en relación con las medidas y prácticas inclusivas. No se hallaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre las actitudes de los docentes y la etapa educativa

Palabras clave: inclusión; actitudes; educación inclusiva; enseñanza inicial; educación primaria

Introduction

While inclusive education is recognized as a human right in Uruguay, (Art. 24; Ley General de Educación, 2008, Art.1; OEI, 2010), it still represents a challenge in practice. It seems that progress in the legal field contrasts with what is put into practice, and there is a gap-in our country and on an international scale-between what the law espouses and what is in fact achieved at the level of educational institutions.

UNICEF, together with the Inter-American Institute on Disability and Inclusive Development (Unicef-iiDi, 2013), has systematized the information available on the subject in Uruguay. At present there are clear examples of inequality regarding disabilities and access to education. By analyzing 21st century policies and strategies for inclusion (UNESCO, 2009), they describe several scenarios in which learners with disabilities are integrated into mainstream public schools with support teachers or itinerant teachers. However, “making progress on inclusive projects in mainstream schools continues to be one of the biggest challenges for the Uruguayan education system” (Unicef-iiDi, 2013; p. 48). The progress made towards implementing inclusive education is slow, a fact that is also reflected in international research (Vislie, 2006; Ferguson, 2008).

Evidence suggests (Unicef-iiDi, 2013; p. 48) a lack of clear models of inclusive education put into practice successfully. For that reason, there is a salient need for educational innovation that can have an impact on classrooms. Quality professional training that is prepared to meet the challenge of diversity, flexibility in the curriculum and in the organizational structure, and, according to international studies, positive teacher attitudes towards inclusion could be key to progress in inclusive education. Do teachers in Uruguay have a positive attitude towards inclusion?

Towards inclusive education

For Booth and Ainscow (2011), inclusive education is a set of processes that aims to eliminate or reduce barriers that limit the learning and participation of all learners. They describe three dimensions: culture, policies, and practices. Culture refers to an educational community with shared values and beliefs oriented towards learning for all. Policies focus on inclusion as the engine of the educational institution and define the different support methods that respond to diversity. Practices guarantee that school activities promote full and effective participation in line with the culture they belong to and the policy guidelines they have (Booth & Ainscow, 2011).

Ainscow (2001) argues that inclusive education allows an educational institution to provide quality education for all learners, whether they have special educational needs (SEN) or not, on the basis of equal opportunities and accepting diversity. According to Echeita (2007; p.15) inclusive education strives to address diversity and answers the question of “how to learn to live with differences, and how to learn from differences.” In the field of education, educating among diversity refers to individual differences as something intrinsic in all people, and not as the specific situation of a certain setting, group, or person (Bravo, 2013). According to Arnaiz Sánchez (2003), diversity is a fact that manifests as differences in ability, interests, motivations, attitudes, thinking styles, and learning styles, among others. As with other countries in Latin America, inclusive education is still conceived of in Uruguay as targeted towards a certain group of learners who have SEN associated with some type of disability. For this reason, the existing initiatives have arisen from the need to modify the curriculum in accordance with differences in learner capabilities, and not on diversity in a broader sense (Cardona, 1995; 2003; Chiner & Cardona, 2013). This obstacle to a paradigm shift is reflected in educational practices that do not yet comply with the inclusive education model.

Eisenman, Pleet, Wandry y McGinley (2011) highlight some of the relevant components necessary for making progress in inclusive education. These include leadership in the educational institution, a collaborative culture, and adapted access to infrastructure, among others. Idol (2006) also indicates certain important indicators of successful implementation of inclusive practices in school settings. These include: the type of disabilities learners have, the use of and number of support staff available, how the members of the educational community perceive their ability to make changes in their teaching methods and in the curriculum, and their ability to control learner discipline and class management. Additionally, Idol (2006) notes that the success of inclusive practices depends on the attitudes of the members of the educational community towards other members, collaborative work, learners with special educational needs and inclusion.

Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion are a determining factor for academic success in a normal classroom environment. (Batsiou, Bebetsos, Panteli, & Antoniou, 2008; Dupoux, Hammond, Ingalls, & Wolman, 2006).

Bravo (2013) defines attitude as a person’s disposition, or learned predisposition to react in a certain way towards an event, person, or situation, and that this manifests in an organized way through experiences, and influences or guides behavior towards objects or situations. Figure 1

According to the contributions of Ajzen and Fishbein (1975), the more inclusive the institutional culture and the educational policies of the institution in which a teacher works, the greater the probability that a teacher with a positive attitude towards inclusion will implement inclusive educational practices in the classroom (subjective norm). Ajzen (1998) added the importance of perceived control over behavior to this model. Teachers will be more willing to change their educational practices the more they perceive that they are able to do so (perceived control over behavior). For that to occur, teachers must feel competent to manage said practices, trained in attending to diversity, and supported on an organizational level by their institution (time for planning and coordination with colleagues).

If attitude is such a determining factor in developing inclusive education, then it is pertinent to wonder whether a negative attitude can be changed, and how to change it. To be able to do so, it is crucial to discover what factors affect teachers’ attitudes.

One relevant theory when considering inclusion and disability is the Intergroup Contact Theory (Allport, 1954), which argues that not all contact has a beneficial effect on attitude change; the quality of the contact between two groups determines whether the vulnerable group is accepted or rejected (Allport, 1954). The theory indicates three factors that promote positive attitudes towards a group of people: equal status of the individuals in a given situation, having common goals, and receiving institutional support.

Attitudes are gradually learned through experience. Thus, if attitudes are acquired over a lifetime through personal experiences, then teaching experience in classrooms with learners with different types of disabilities-and therefore experience in serving diverse needs-can influence teachers’ perceptions of the issue and consequently their attitudes towards inclusive education.

Research on teachers’ attitudes

Current research has not produced conclusive results when describing teachers’ attitudes or determining which factors influence positive attitudes (Verdugo, 2002). However, it is agreed that positive attitudes towards people with disabilities tend to improve these learners’ educational prospects (Merino & Ruiz, 2005; en Sanhueza, Granada & Bravo, 2013). Chiner (2011) claims that teachers’ attitudes are affected by factors related to the body of learners, the teachers, and the context. This study will consider the factors related to the teachers and the context.

De Boer, Pijl and Minnaert (2011) carried out a literature review of 26 studies on teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. They posit that most teachers have a neutral or negative attitude towards including learners with SEN in mainstream education, and that the factors that have an impact on these attitudes include training, gender, years of experience in inclusive settings, and the type of educational needs of the learners.

One of the first teacher-related factors to consider is professional training. Nowadays, after receiving basic training, a teacher is expected not only to be competent in the subject matter he or she must teach, but also capable of encouraging all learners to learn and participate and fostering opportunities for educational development and inclusion (Sola, 1997). He or she should have the tools to provide quality educational solutions for diverse learners in the teaching-learning process. Similarly, a teacher should expect ongoing training throughout his or her professional career that provides the up-to-date skills and knowledge necessary to meet potential future demands.

To this effect, there are also various studies that refer to teachers calling for further training. Sánchez, Díaz, Sanhueza and Friz (2008) claim that 92% of student teachers indicate that teachers in mainstream education do not have the training necessary to address the needs of learners with SEN. Different studies signal the importance of teacher training as a deciding factor in making inclusive education possible (Arnaiz 2003; Stainback & Stainback, 1999). De Boer et al. (2011) indicate that teachers do not feel well prepared to serve the needs of the learners with disabilities in their classrooms. To this effect, teachers with more training have a more positive attitude than those with less training.

Studies show that another relevant factor to consider when analyzing teacher attitudes is teaching experience. Teaching experience is understood as the time a teacher has spent practicing professionally that has allowed him or her to discover, develop, and experience a particular educational practice. Past studies indicate that years of experience have an influence on attitudes towards inclusive education. Teachers with less years of teaching experience show more positive attitudes than those with more experience.

Similarly, teachers with previous experience in inclusive education show more positive attitudes than those with less experience in inclusive settings (De Boer et al., 2011). Sanhueza, Granada, and Pomés (2013) point out that in this vein it is possible to analyze teachers’ experiences in two ways: on the one hand, in terms of the number of years a teacher has worked, and on the other, in terms of previous experiences associated with inclusive practices. In the first case, more years of teaching does not favor inclusive education, whereas specific experience with inclusive education does positively impact attitude. It is worth mentioning that it is not just contact or previous work with people with disabilities alone, but experience in inclusive settings. Avramidis y Norwich (2002) affirm that there is no significant relationship between contact with people with disabilities and a positive attitude towards inclusion, and that addressing the needs of learners with disabilities in normal classrooms can cause stress which negatively affects teachers’ support of inclusion.

There are two factors that are considered essential in relation to context. One of these is the possibility of having the time, space, and opportunity to plan, coordinate, and collaborate on putting different diversity-serving pedagogical actions into practice. In this regard, Sanhueza et al., (2011) establish that material resources and time continue to be seen by teachers as an obstacle to developing inclusive practices.

Another context-related factor that influences teachers’ attitudes within the framework of inclusive education is access to support resources. Support serves as the means by which institutions strive to address diversity in the classroom. There are two types of support: human resources (professionals, assistants, colleagues, and family) and material resources (inclusive practices). Seventy-seven percent of educators believe that the best option for educating learners with SEN is through general education with sufficient teaching assistants to work with each learner who needs support (Idol, 2006).

Material resources include adapted curricula and inclusive teaching and learning strategies (collaborative work, co-teaching, or multilevel activities, among others). There is evidence that educational institutions that employ diverse forms of support and varied teaching strategies can be effective in catering to diversity, and achieve good academic results (Jordan, Glenn & McGhie-Richmond, 2010). In previous studies in the U.S. and Canada relating to material resources, teachers signal the need to reduce the number of learners per class (Horne & Timmons, 2009).

Curone and Di Segni (2014) carried out a pilot study on how teachers at two private schools in Montevideo perceive and conceive of including learners with special educational needs, and the strategies used in teaching. Although the results are not conclusive because of the small sample size, the study indicates that the perceptions and attitudes of the teachers towards inclusion were moderately positive, and teacher-related variables do not appear to be determining factors for attitude, which leaves the door open for a new line of research on context-related variables (available support, among others).

Taking into account developments in inclusive education since the late 1990’s, and the lack of research on the topic in this country’s context, the current study has the following aim: to determine the attitudes of preschool and elementary school teachers in a private school in Montevideo towards inclusive education. To do so, the first objective of the study will be to describe the attitudes that preschool and elementary school teachers in this institution have towards inclusion. The second aim will be to analyze whether these attitudes vary by teacher-related variables (teacher’s position, academic background, previous teaching experience with people with disabilities, educational stage, and years of professional experience), and lastly, to investigate which types of inclusive practices teachers favor implementing in their classrooms.

Method

The study chose a non-experimental, cross-sectional, descriptive design that employed a survey. Given that attitudes cannot be directly measured, the study opted to rely on opinions as an indicator of the participants’ attitudes. This methodological choice is consistent with quantitative approaches discussed by several authors (Albert, 2007; Hernández, Fernández, & Baptista, 2010).

Participants

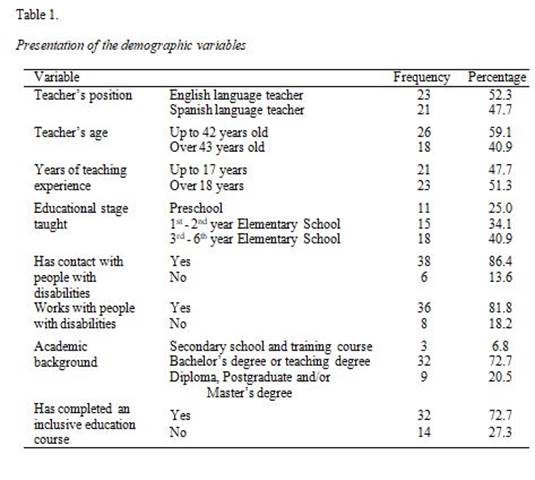

By means of convenience, non-probability sampling, the voluntary survey was applied to all English and Spanish language teachers of preschool and elementary education of a private school in Montevideo. A total of 44 participants were gathered. Table 1 shows frequencies and percentages of socio-demographic variables.

Characteristics of the educational institution

The institution is a bilingual school located in a residential neighborhood of Montevideo. In recent years, they have begun to consider diversity in their classrooms by implementing different types of support: in the classroom, outside the classroom, after school coaching, curricular adaptations, learning tutors, and even from 2016, an “Aula Estable” support method was implemented (Sola, 2013). Under this method, during part of the day, learners in this group receive individual intervention in the areas of greatest difficulty and carry out a program that contemplates their interests and needs in a resources classroom, and during the other part of the day, they are in the regular classroom with the appropriate adjustments, if necessary. They have approximately seven hundred learners, considering preschool and elementary education. There is a total of 54 teachers (n = 54) among substitute, area-specific, and regular teachers. At the end of elementary school, learners may optionally take an international examination in English as their mother tongue, in the areas of language, natural sciences and mathematics.

From early childhood education to first year, a teaching assistant accompanies the group throughout the day. There is also an Educational Guidance Team, which consists of psychologists specialized in educational psychology, learning tutors, educational psychologists, teachers specialized in learning difficulties, and psychomotor specialists. The Preschool and Elementary School Director leads a group of coordinators of English and Spanish in preschool and elementary school, physical education and sports, pastoral and educational guidance. She is part of the Faculty Board, together with the General Director, the High School Director, the Administrative Director, the General Coordinator of English Language, and the General Pastoral Coordinator.

According to the Uruguayan legislation, each educational center is responsible for coordinating non-significant and significant curricular adjustments, as well as access adjustments for learners with special educational needs. Regarding the presence of learners with disabilities in the regular classroom, the indicator used for their identification are the curricular adaptations applied. Six per cent of the preschool and elementary education learners have some kind of curricular adaptation.

Measurement instrument

The instrument used was the Inclusive Education Opinion Scale. The instrument was designed and adapted by Cardona (2013) based on other similar instruments used in previous studies (Cardona, 2006; Cornoldi, Terreni, Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1998). It is a multidimensional scale with very good reliability values (Cronbach’s alpha = .84) and validity (IVC = 0.95).

It consists of a first part with a socio-demographic questionnaire. Three items were included, one in reference to the attendance or not to training courses on inclusion, another to having or not having contact with people with disabilities, and the last one to having worked or not with people with disabilities. The second part is a Likert opinion scale. It consists of 23 items distributed in three sub-scales. The first sub-scale is about the “Foundations of Inclusive Education” and aims at identifying the attitudes of teachers towards the fundamental principles of the concept of inclusion. The second sub-scale, called “Conditions for Inclusive Education”, is about the scope of available supports, human resources, materials, training, and education. The last one is called “Measures to Address Diversity”, which aims at identifying the degree of agreement with institutional practices and measures, whether of a technical or administrative nature, which favor inclusion.

Rating of each item ranges from “strongly disagrees” (MD = 1), “disagrees” (ED = 2), “agrees” (DA = 3), “strongly agrees” (MA = 4) and “does not know or does not respond” (DK / NR = 5). Scores are arranged positively, that is, the higher the score, the more favorable is the teacher’s attitude.

Table 2 shows the results of the analysis of internal consistency coefficients of the instrument for this study, using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

Ethical standards and procedure

After requesting the corresponding authorizations in the educational center, we proceeded to give the school’s English and Spanish teachers informed consent. The aim of the research was explained, guaranteeing the confidentiality of the results, and it was provided by a single researcher.

The statistical package SPSS.22 was used to create the database and subsequent analysis. Regarding the description of the sample, frequencies, percentages, and averages were used. Average comparison studies were carried out with the factors of the scale, taking into account the different independent variables. For such purpose, Mann-Whitney’s U and Kruskall Wallis were used for more than two independent groups.

Results

The aim of this research was to describe the attitudes of preschool and elementary education teachers in a private school in Montevideo towards inclusive education, and analyze whether they varied according to some demographic variables, such as: teaching experience, his or her position as a teacher, academic background, having had contact with people with disabilities, having worked with people with disabilities, and the educational stage. Finally, to investigate what kind of inclusive practices teachers are most in favor of putting into practice.

The results of the descriptive statistics of the answers given by the teachers in the Inclusive Education Opinion Scale, organized according to the factor solution used by Bravo (2013), are hereby presented.

The average of teachers, regarding the foundations of inclusion (see Table 3), was M = 3.35 (DE = .55), above the midpoint of the scale (x = 2.50), thus indicating an opinion clearly favorable to the fundamental principles of inclusion.

Fifty-two per cent of respondents agree that all learners benefit academically from being in regular classrooms, and 70% agree or strongly agree that all learners benefit socially in inclusive schools. The majority (68%) also maintains that inclusion is possible in all educational stages and that inclusion has more advantages than disadvantages.

Regarding the conditions provided by the center to carry out inclusion, personal conditions to carry it out, the opinion of teachers was moderately favorable (M = 2.95), as shown in Table 3. Eighty-three per cent of teachers agree or strongly agree that they have enough support from the faculty board and the educational guidance team. Regarding having the necessary skills to deal with diversity in their class, 46% feel they do not have them, and 70% indicate that they are not sufficiently qualified to serve students with SEN. On the other hand, 72% of respondents feel they do not have enough time to help their students.

Regarding the measures to address diversity (inclusive practices), teachers agreed strongly (M = 3.69). Sixty-eight per cent of participants agree or strongly agree with the implementation of curricular access or non-significant adaptations. Also, with the application of significant adaptations, collaborative work and co-teaching between regular and special teachers. Another inclusive measure with strong adherence by this group of teachers is the implementation of multilevel activities (88%), and evaluation according to individual standards (84%). All teachers point to the need for more training.

Analysis of comparison of averages, and its relationship with socio-demographic variables

Average comparison studies were carried out with the factors of the scale, taking into account the variable of teaching experience. The results presented in Table 4 show that there is a statistically significant difference (p ≤ .05) in the factor “Inclusive Measures and Practices”. This difference indicates higher scores of the group with more years of experience.

Secondly, tests were carried out with respect to the teacher’s position variable. Table 5 shows the comparison of averages, showing a significant difference in the factor “Foundations of Inclusive Education” (p = .031). Spanish language teachers have a more favorable view towards inclusive education, regarding general principles, than English language teachers.

Tests were then performed according to the rest of the variables, but no statistically significant differences were found.

Discussion and Conclusion

Progress towards more inclusive cultures in every educational institution is a process that takes time, as it would be the result of the transformation of their educational policies, as well as the assimilation and adoption of innovative and inclusive educational practices by teachers, in a culture that is gradually accepting diversity.

The key of educational change is the teacher. Teachers can be facilitators or barriers to it. Their attitude towards the implementation of inclusive educational practices can promote full and effective participation of learners, or can minimize it.

The results in this study indicate that teachers have a positive attitude towards the principles of inclusive education. The attitude of Spanish teachers is more positive towards this factor than that of their English colleagues. On the one hand, this difference can be attributed to the fact that the language area is where most of the learners’ learning difficulties converge. In learning a second language, these difficulties are even more evident. Spanish teachers have other areas where they can exploit the strengths of learners. On the other hand, towards the end of elementary education, students have the option to take an international exam. This external examination guides educational practice, in some way, towards the achievement of the international standards required, especially in the last years of elementary education.

Previous studies indicate that, although teachers can agree with the fact that learners have the right to be in the normal classroom with the required supports, when put it into practice in their own classrooms and having the responsibility that all learners achieve high academic levels in addition to significant learning, they may manifest greater concerns. English teachers may perceive less flexibility to personalized learning and apply curricular diversification programs with learners whose academic competences differ significantly from the majority of the group-class for the purpose of performing an external standardized assessment (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007; Cornoldi et al., 1998, Valeo, 2008).

With respect to the conditions for carrying out inclusive education, teachers demand more time and more training to deal with diversity in the regular classroom (Alghazo and Naggar, 2004; Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Cardona, 2003). The attitude of these teachers to this sub-scale was favorable, however, it was not so much when compared with that of the other two sub-scales. Teachers’ continuing education, and of those responsible of training teachers, as well as perceiving they do not have enough time to deal with diversity in the classroom, emerged as essential when defining strategies to favor inclusion.

More experienced teachers have a more favorable attitude towards the implementation of inclusive practices. It is necessary to contextualize the term teacher experience in this case. It should be noted that 73% of teachers have some training on inclusion, 86% reported having had contact with people with disabilities, and 82% work with people with disabilities. It follows that teachers use a broad concept of the term disability, and have training in this regard. In this sense, this result matches that obtained in previous research: the greater the experience in inclusive contexts, the more favorable the opinion in this regard.

Among the participants, there is a broad consensus on the benefits of the implementation of inclusive practices. This contrasts with the conditions teachers perceive they have, in the sense that they feel they need training, and that they lack the skills and time to do it. Precisely, implementing inclusive practices, such as the proposal of multilevel activities -strategy of personalization of basic education to address diversity (Arnáiz, 2003, Echeita, 2007, 2008)- requires acquiring skills in classroom planning, classroom management, flexible groupings, as well as time.

The faculty board of this institution has the challenge of maintaining this positive attitude in teachers. For this purpose, according to the research contributions of Horne & Timmons (2009), it will be necessary to provide greater administrative support, planning time, and training on pedagogical strategies. In this way, the teacher’s perceived control will be greater, so his or her intention to implement inclusive practices will be even more favorable (Ajzen, 1988, Allport, 1954).

Likewise, it would be advisable to continue to promote collaborative work, especially among the most experienced teachers with their less experienced colleagues. In order to promote better conditions to carry out inclusive education, it would also be positive to optimize pedagogical support per learner, by encouraging the support teacher to work during more instances within the normal classroom.

Likewise, in order to create an increasingly inclusive culture, it would be advisable to offer workshops on the rights of people with disabilities, and the opportunity of the educational community to eliminate the barriers that hinder full participation and, in this aspect, perhaps to also involve parents in a planned manner, as they are the first potential agents to promote positive attitudes towards people with disabilities.

Knowing the attitudes of teachers is even more important nowadays, considering the context of Uruguay, where educational policies and existing legislation begin to be reflected in greater number of students with some type of disability in normal classrooms. These attitudes reflect the way in which inclusion develops in practice. In view of the results of this study, some proposals for both future research and practice arise.

In the current context of education in our country, it is possible to think that, in the daily work of a large number of teachers, several of these factors are making an impact on their attitude towards the new demands of a more inclusive educational approach. Teachers with inadequate initial education and training for the current context, with little time to plan their work, and without previous experience dealing with diversity will be more likely to express a negative attitude.

At the level of professional training, there is a need for substantial change. Considering the issue of inclusion, teachers must graduate being competent in the choice and use of teaching strategies to deal with diversity. In order to do so, it will also be necessary to train teacher trainers.

Undoubtedly, the need to have formal education and training to deal with diversity, with an adequate administrative organization to promote planning time and collaboration among teachers, as well as and enough human resources, it can be extrapolated to the context of our education in general. All these elements limit or facilitate the attempts of teachers to generate more inclusive practices.

As a line of research for future studies, it would be interesting to investigate the implementation of inclusive practices and their impact on classrooms. Will its use be determined by an appropriate professional training? By having the time necessary? By having a clear institutional stance? Or by the teacher’s openness to change? Resistance to change is an important variable to consider. According to the results obtained in the PISA evaluation in 2015, Uruguay is among the top five countries with the greatest resistance to change by teachers. This is an indicator that in our country emerges as problematic in all stages, and has been increasing since 2003 (Ravela, 2017).

Although the results obtained are generally consistent with those of previous international studies (Chiner, 2011; De Boer et al., 2011), it is necessary to consider the limitations of the present study. It should be noted that in descriptive studies by means of a survey, it is necessary to consider the margin of error of the information obtained, since it is possible that the sample has been influenced by “social desirability.” Likert scales as an instrument for measuring attitudes have some limitations as well, since when working with average scores, some extreme answers may not have been reflected in the results of the study.

The changes that inclusive education must generate in a school are structural changes that require the joint work of the whole educational community: faculty board, teachers, students, and families. A community with a clear leadership guiding the necessary educational policies, so that the different factors that influence educational work have a positive impact on the attitudes of those who have in their hands the possibility of innovation.

Referencias

Ainscow, M. (2001). Desarrollo de escuelas inclusivas. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. (1988). From intentions to actions. En I. Ajzen (ed.). Attitudes, personality and behaviour. Chicago: The Dorsey Press. [ Links ]

Albert, M. (2007). La Investigación Educativa. Claves Teóricas. España: Mc Graw Hill. [ Links ]

Alghazo, E. & Naggar Gaad, E. (2004). General Education Teachers in the United Arab Emirates and Their Acceptance of the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 31(2), 94-99.doi: 10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335 [ Links ]

Allport, G.W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Arnaiz-Sánchez, P. (2003). Educación Inclusiva: una escuela para todos. España: Aljibe. [ Links ]

Avramidis, E. & Kalyva, E. (2007). The Influence of Teaching Experience and Professional Development on Greek Teachers` Attitudes towards Inclusion. European Journal of Special Needs education, 22(4), 367-389. doi:10.1080/08856250701649989 [ Links ]

Avramidis, E., & Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers` attitudes towards integration inclusion: a review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs education ,17(2),129-147. DOI:10.1080/08856250210129056 [ Links ]

Batsiou, S., Bebetsos, E., Panteli, P., & Antoniou, P. (2008). Attitudes and Intention of Greek and Cypriot Primary Education Teachers towards Teaching Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(2), 201-219. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603110600855739 [ Links ]

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2011). Índex para la inclusión. Guía para la evaluación y mejora de la educación inclusiva. Madrid: Consorcio Universitario para la Educación Inclusiva. [ Links ]

Bravo, L. (2013). Percepciones y opiniones hacia la educación inclusiva del profesorado y de los equipos directivos de los centros educativos de la dirección regional de Cartago en Costa Rica. (Tesis doctoral Inédita). Universidad de Alicante. [ Links ]

Cardona, M. C. (1995). Respuesta a la diversidad: modelos de intervención psicopedagógica. Qurriculum: Revista de teoría, Investigación y Práctica, 10(11), 27-48. [ Links ]

Cardona, M. C. (2003). Inclusión y cambios en el aula vía adaptaciones instructivas. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 21(2), 465- 487. doi: 10.1016/0193-3973(81)90032-0 [ Links ]

Cardona, M. C. (2006). Creencias, percepciones y actitudes hacia la inclusión una síntesis de la literatura de investigación. En C., Jiménez-Fernández, (Coord.), Pedagogía diferencial. Diversidad y equidad: 239-266. Madrid: Pearson. [ Links ]

Cardona, M.C. (2000). Regular classroom teachers ‘perceptions of inclusion: Implications for teacher preparation programs in Spain. En C. Day (Ed.), Educational Research in Europe, (pp. 37-47). Louvain: Garant & European Research Association. [ Links ]

Cardona, M. C. & Bravo, L. (2010). Escala de opinión hacia la educación inclusiva. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante. [ Links ]

Chiner, E., & Cardona, C. (2013) Inclusive education in Spain: How do skills, resources, and supports affect regular education teachers’ perceptions of inclusion? University of Alicante. [ Links ]

Chiner, E. (2011). Las percepciones y actitudes del profesorado hacia la inclusión del alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales como indicadores del uso de prácticas educativas inclusivas en el aula. (Tesis doctoral Inédita). Universidad de Alicante. [ Links ]

Cornoldi, C., Terreni, A., Scruggs, T., & Mastropieri, M. (1998). Teacher`s attitudes in Italy. After twenty years of inclusion. Remedial and Special Education, 19, 350-363. http://rse.sagepub.com/content/19/6/350. doi: 10.1177/074193259801900605 [ Links ]

Curone, G., & Di Segni, L. (2014). Percepciones y actitudes de los docentes hacia la inclusión y sus prácticas. Memoria final de Postgrado. Universidad Católica del Uruguay. [ Links ]

De Boer, A., Pijl, S., & Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers` attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education , 15(3), 331-353. doi:10.1080/13603110903030089 [ Links ]

Dupoux, E., Hammond, H., Ingalls, L., & Wolman, C. (2006). Teachers’ attitudes toward students with disabilities in Haiti. International Journal of Special Education, 21(3),1-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1030011200022600 [ Links ]

Echeita, G. (2007). Educación para la inclusión. Educación sin exclusiones. Madrid: Narcea . [ Links ]

Echeita, G. (2008). Inclusión y exclusión educativa. “Voz y quebranto”. Revista Electrónica Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 6(2), 9-18. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2012.700563. [ Links ]

Eisenman, L. T., Pleet, A. M., Wandry, D., & McGinley, V. (2011). Voices of special education teachers in an inclusive high school: Redefining responsibilities. Remedial and Special Education 32, 91-104. doi: 10.1177/0741932510361248 [ Links ]

Ferguson, D. (2008). International Trends in Inclusive Education: The Continuing Challenge to Teach Each One and Everyone. European Journal of Special Needs education , 23(2), 109-120. doi: 10.1080/08856250801946236 [ Links ]

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2010). Metodología de la investigación. Madrid: Pearson . [ Links ]

Horne, P. E., & Timmons, V. (2009). Making it work: Teachers’ perspectives on inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education ,13, 273-28. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603110903046010. [ Links ]

Huh, J., Delorme, D.E., & Reid, L.N. (2006). Perceived Third Person Effects and Consumer Attitudes on Preventing and Banning DTC Advertising. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 40(1), 90-116. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00047.x [ Links ]

Idol, L. (2006). Toward Inclusion of Special Education Students in General Education. A Program Evaluation of Eight Schools. Remedial and Special Education , 27, 77-94. doi:10.1177/07419325060270020601 [ Links ]

Jordan, A., Glenn, C., & McGhie-Richmond, D. (2010). The Supporting Effective Teaching (SET) project: The relationship of inclusive teaching practices to teachers’ beliefs about disability and ability, and about their roles as teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 259-266. [ Links ]

Ley General de Educación Nro. 18.437. Asamblea General del Uruguay. (2008). Disponible en: http://www.bibna.gub.uy/ [ Links ]

Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos para la Educación, la ciencia y la Cultura. (2010). Metas Educativas 2021. La Educación que queremos para la generación del Bicentenario. Disponible en: http://www.oei.es/metas2021. [ Links ]

Ravela, P. (2017). Once aspectos en los que el sistema educativo uruguayo se destaca en el concierto internacional. Recuperado de: http://www.180.com.uy/articulo/66898_once-aspectos-en-los-que-el-sistema-educativo-uruguayo-se-destaca-en-el-concierto-internacional [ Links ]

Sánchez, A., Díaz, C., Sanhueza, S., & Friz, M. (2008). Percepciones y actitudes de los estudiantes de pedagogía hacia la inclusión educativa. Estudios pedagógicos, 2: 169-178. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052008000200010. [ Links ]

Sanhueza, S., Granada, M., & Bravo, L. (2012). Actitudes del profesorado de Chile y Costa Rica hacia la inclusión educativa. Cuadernos de pesquisa, 42(147), 844-899. doi: 10.1590/S0100-15742012000300013 [ Links ]

Sanhueza, S., Granada, M., & Pomés, M. (2013). Actitud de los profesores hacia la inclusión educativa. Papeles de trabajo-Centro de Estudios Interdisciplinarios en Etnolingüística y Antropología Socio-Cultural, (25) Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1852-45082013000100003&lng=es&tlng=es. [ Links ]

Sola, T. (1997). La formación inicial y su incidencia en la educación especial. En Sánche Palomino, A. y J. Torres González, Educación especial I. Una perspectiva curricular, organizativa y profesional. Madrid: Pirámide. [ Links ]

Solla, C. (2013). Guía de Buenas Prácticas en Educación Inclusiva. Madrid: Save the children. [ Links ]

Stainback, W. & Stainback, S. (1999). Aulas inclusivas. Madrid: Narcea . [ Links ]

UNESCO (2009). Estrategia de la OIE para 2008-2013. Ginebra Suiza. , UNESCO/OIE. [ Links ]

UNICEF-iiDi (2013). La situación de niños, niñas y adolescentes con discapacidad en Uruguay. La oportunidad de la inclusión. Montevideo: Mastergraf. [ Links ]

Valeo, A. (2008). Inclusive education support systems: Teacher and administrator views. International Journal of Special Education , 23(2), 8-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9604.2011.01480 [ Links ]

Verdugo Alonso, A. (Dir.) (2002). Persona con discapacidad: Perspectivas psicopedagógicas y rehabilitadoras. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Vislie, Lise. (2006). Special education under the modernity. From restricted liberty, through organized modernity, to extended liberty and a plurality of practices. European Journal of Special Needs education , 21, 395-414. doi: 10.1080/08856250600956279 [ Links ]

Received: March 11, 2017; Revised: August 17, 2017; Accepted: September 24, 2017

texto en

texto en