Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ciencias Psicológicas

versão impressa ISSN 1688-4094versão On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.11 no.2 Montevideo nov. 2017

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v11i2.1490

Original Articles

Conjugality and late coparenting

1,,Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia da Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos. Brasil fidelisdaiana@gmail.com dfalcke@unisinos.br clarissepm@unisinos.br

Abstract: This study aimed to understand the transition from conjugality to late coparenting in dual career-couples. Five heterosexual couples in which women got pregnant after aging 35 years old, displaying professional activities, and having a firstborn child aged up to one year old participated in the study. Exclusion criterion was participants who have undergone any type of fertilization treatment. Instruments were a sociodemographic questionnaire and a semi-structured interview. The results point out changes in marital and coparenting relations. Fathers demonstrated to be collaborative throughout gestation period and mainly after child’s birth, splitting care tasks with their wives, as well as home tasks, which were reflected in high levels of coparenting agreements articulated with good marital quality. Although the investigated couples demonstrated high workloads, the majority of them seemed satisfied about their jobs due to employment flexibility, thus parents were able to conciliate their career with parenting

Key Words: conjugality; coparenting; late gestation; dual career couples; qualitative investigation

Resumo: Este estudo buscou compreender a transição da conjugalidade para a coparentalidade tardia em casais com dupla carreira. Teve âmbito exploratório, descritivo e qualitativo. Participaram cinco casais heterossexuais, ambos com profissionais, filho primogênito de até um ano de idade e com mais de 35 anos. Como critério de exclusão, não poderiam ter realizado tratamento de fertilização. Utilizou-se um questionário sociodemográfico e uma entrevista. Os resultados apontaram modificações nas relações conjugais e coparentais. O pai se mostrou presente durante a gestação e principalmente depois do nascimento do filho, dividindo as tarefas de cuidados e tarefas domésticas, refletindo altos níveis de acordo coparental e, boa qualidade conjugal. Os casais deste estudo ainda que com grande carga horária de trabalho se mostraram satisfeitos com seu emprego por terem flexibilidade, permitindo conciliar trabalho e parentalidade

Palavras chave: conjugalidade; coparentalidade; gravidez tardia; casal de dupla carreira; pesquisa qualitativa

Resumen: Este estudio buscó comprender la transición de la conyugalidad a la coparentalidad tardía en parejas de doble carrera. Tuvo alcance exploratorio, descriptivo y cualitativo. Participaron cinco parejas heterosexuales, profesionales, hijo primogénito hasta un año de edad, y mujeres mayores de 35 años. Como criterio de exclusión, no podían haber hecho tratamiento de fertilización. Se utilizó un cuestionario sociodemográfico y una entrevista. Los resultados han señalado cambios en la conyugalidad y coparentalidad. El padre se mostró presente durante el embarazo y en especial después del nacimiento del hijo, compartiendo las tareas de atención, así como las tareas del hogar, lo que refleja los altos niveles de acuerdo coparental y una buena calidad conyugal. Las parejas de este estudio aunque con una alta carga horaria de trabajo, se mostraron satisfechas con su empleo por tener flexibilidad, lo que les permite conciliar trabajo y parentalidad

Palabras clave: conyugalidad; coparentalidad; embarazo tardío; parejas de doble carrera; investigación cualitativa

The transition from conjugality to coparenting is a moment of great importance in the family life cycle, as it demands a reorganization of the couple, since it generates changes in the image of the self, the other and the relationship itself (Prati & Koller, 2011). This moment of the evolutionary lifecycle, focusing on parenting, has been studied in the Brazilian and international context for more than 30 years and the results indicate the importance of emotional support between the spouses at that moment time, as well as the involvement of both in the process (Dorsey, Forehand, & Brody, 2007; Teubert & Pinquart, 2010; Piccinini, Silva, Gonçalves, Lopes, & Tudge, 2004; Piccinini, Gomes, Nardi, & Lopes, 2008; Menezes & Lopes, 2007; Lee & Doherty, 2007; Beltrame & Botolli, 2010). Specifically about the transition to coparenting, studies remain scarce. The relevance of studying this dimension in this process is maintained, unlike parenting, as a construct of a relational nature between the spouses / parents.

Coparenting is understood as the sharing of the child’s care and duties between the couple (Feinberg, 2003). The coparental subsystem is based on four dimensions: agreement or disagreement on parental practices, division of child-related work, support / sabotage of coparental role and joint management of family relationships.

This construct differs from the marital relationship, as it does not contemplate the legal, romantic, sexual, emotional and / or financial aspects, which are not related to the child’s care (Feinberg, 2003, Holland & McElwain, 2013, Jia & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2011), and it is distinct from parenting, as it is not restricted to the parents’ styles and practices in educating the children (McHale et al., 2002).

According to the literature, although different from conjugality, the quality levels of coparenting stem from the articulation between characteristics of the marital relationship and of parenting, which will result in the coparental dynamics between the parents (Morril, Hines, Mahmood, & Cordova, 2010). In this sense, the emotional support between the spouses has been highlighted as of great importance for the marital relation during the pregnancy, in view of the reflexes it will entail after the baby’s birth. Brazilian (Menezes & Lopes, 2007) and international studies (Lee and Doherty, 2007) argue that high levels of marital quality in the transition to parenting are essential because they are associated with the father’s increased involvement with the children. It should be emphasized that this dynamic should be established prior to the transition, as the difficulties inherent in the process are inevitable.

There is a consensus in the literature on the importance of conjugality in the transition to coparenting and, consequently, in the psychological adjustment of the children and the family functioning (Dorsey et al., 2007; Teubert & Pinquart, 2010; Lamela, Nunes-Costa, & Figueiredo, 2010). This subsystem needs to be understood in a current context of multiple demands though. Couples are currently reconciling personal, marital, family and professional life, which leads to a burden as a consequence of the multiplicity of roles (Lamela et al., 2010).

Therefore, the question raised is how the transition from conjugality to coparenting occurs in the dual-career context of the spouses, who are working full-time (Heckler & Mosmann, 2014). Demands of personal, marital and professional life and also childcare lead to challenges and overloads (Aryee, Srinivas, & Tan, 2005; Demerouti, Bakker, & Schaufeli 2005), characterizing one of the greatest challenges in the lives of dual-career families, which has made many couples postpone maternity / paternity.

Some studies indicate that many women postpone having children because they first want to gain financial stability, focused on solidifying their career and gaining professional success, and then think about getting pregnant. This extension of maternity is done until achieving the condition the couple considers appropriate for this responsibility or, even, the option for non-maternity (Grzywacz, Almeida, & McDonald, 2002).

The postponement of maternity / paternity has also occurred due to options not related to professional life, as shown in the research by Ronchi and Avellar (2011). The results indicated that the decision to have children later came from both the woman and the man, linked to the desire to carry out other plans before entering into parenting. Among the causes for late pregnancies, above 35 years, there is the widespread availability of contraceptive methods, the delay of marriage, the higher incidence of divorces, the desire to reach a higher educational and professional level, to achieve safety and financial independence, to accomplish dreams, to enjoy travel and entertainment, and to improve artificial fertilization techniques (Zavaschi, Costa, Brunstein, Kruter, & Estrella, 1999; Schupp, 2006).

In the study by Bauer and Kneip (2013), couples’ decision to have children late was associated with the consonance of the two partners’ desires. Studies indicate that this alignment is associated with good levels of marital quality that entail higher levels of coparental adjustment after the birth of the child (McHale & Rotman, 2007; Vanalli & Barham, 2012). This adjustment appears in the literature also associated with greater paternal involvement in this context of multiple demands (Piccinini et al., 2004; Beltrame & Botolli, 2010). The results indicate that the spouses report providing emotional and material support to their wives during pregnancy, who show satisfaction. Due to the long working day, spouses end up having little leisure time with their children, but they evaluate to be affectionate and say that when they are present, they share the responsibilities for the children with their wives.

Although male participation in childcare and household chores is increasingly balanced with female involvement (Lavee & Katz, 2002; Coltrane, 2000; Dessen & Braz, 2000), women still devote twice as much as men to taking care of the children, washing and ironing clothes, buying groceries, cleaning the house, among others (Baxter, Hewitt, & Haynes, 2008; Hernandez & Hutz, 2010; Vanalli & Barham, 2012). The question is raised whether currently, the option to get pregnant after the age of 35, after the spouses have reached professional stability, can occur in an environment in which both can have more time to share tasks after the birth of the children. In addition, support from the workplace becomes critical.

The results by Oliveira, Galdino, Cunha and Paulino (2011), who qualitatively analyzed the experience of pregnancy in women after 35 years of age, show that, being financially consolidated and living in a stable marital union, women were able to choose to reduce their workload and to be closer to their children. The results of the study by Cruz and Mosmann (2015), which aimed to understand the perceptions of couples about their marital relationship in the transition to parenthood in the context of planned pregnancy, corroborate this perspective. The couples reported that the length of the relationship prior to parenting and the fact that they had already completed their academic and professional plans were fundamental for both to be more available and for the transition process to occur in a less wearisome manner for the couple.

On the other hand, some studies report that the difficulties in the process of transition to coparenting would be the same as in pregnancies of couples before 35 years, associated with physical exhaustion due to the few hours of sleep, added to domestic tasks, as well as a decreased investment in the professional career, which implies a high financial cost. In addition, the wear in the marital relationship of these couples who take longer to have children is noteworthy, as they often lived a significant time only between the two, resenting more because they spend less time just the two, which is reflected in their sexuality (Soares, 2012; Matos & Magalhães, 2014).

It is identified that the emotional implications of this context of pregnancy over 35 years of age and dual career in the transition from conjugality to coparenting still require more national studies. Considering this scenario of transformations, we sought to investigate the transition from conjugality to late coparenting in couples with a dual career.

Materials and Methods

A qualitative and exploratory research was undertaken.

Participants

Five heterosexual couples with first-born children, conceived by women over 35 years of age, both working and living in metropolitan Porto Alegre, participated in this study. The number of five couples was defined by the difficulty found in accessing couples who met the criteria for inclusion in the sample and who felt comfortable talking about their experiences, since many women after 35 years of age have already made attempts to become pregnant, which were not successful, making them feel uncomfortable. Inclusion criteria were: spouses who were married or had lived together for at least two years; only one child up to one year of age; in a dual career. As exclusion criteria, the participants could not have undergone any type of fertilization treatment, since the aim was to investigate couples who chose pregnancy after the age of 35, without any biological impediment.

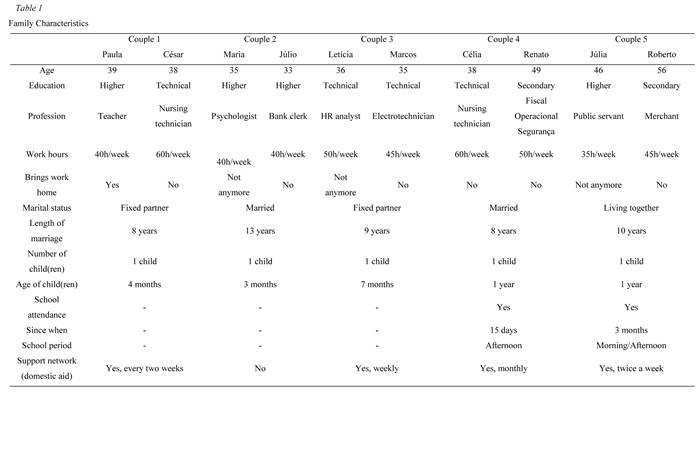

As shown in Table 1, participants were between 33 and 56 years of age, with work hours starting at 35 hours per week. Regarding the couples’ education, two finished high school, four held a technical degree and four an undergraduate degree. In relation to marital status, only one couple does not live with a fixed partner or is married, but merely lives together. Of the five participating couples, three of the mothers were on maternity leave, and were consequently taking care of the children. In the other two couples, the children were already attending school.

Ethical procedures and data collection

After the University’s Ethics Committee had approved the study under opinion 15/231, the data collection started. The participants’ selection process was by convenience. The couple was invited to participate in the research, signed the Free and Informed Consent Form and answered the interview by the researcher.

Instruments

- Sociodemographic data questionnaire. Developed by the authors of the research, aimed to collect information on the family, such as the education level, length of the relationship, professional information.

- Interview on coparenting. The semistructured interview on coparenting contains 31 questions and addresses the following axes: Conjugality, Care Sharing, Engagement in activities with the family and Career. It was developed by the Study and Research Group on Developmental Disorders at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul - UFRGS (Study and Research Group on Developmental Disorders -NIEPED-, 2006) and adapted to address the research objective.

Data analysis procedure

Content analysis was used, which according to Minayo (1994) is a data analysis procedure that is intended to examine the communication with the aim of obtaining indicators that permit knowledge inferences on the conditions in which the messages are produced. The recorded and transcribed interviews were submitted to content analysis and the categories were defined in a mixed form, a priori and a posteriori (Franco, 2005). The a priori categories were based on the interview about coparenting and the a posteriori categories emerged from the interviews.

Results and Discussion

The structure of the categories and subcategories used is displayed in Table 2. The participants’ statementswere fully transcribed and discussed in light of the theoretical framework proposed in the introduction.

Conjugality

This category addresses contents on how the couples related before and after the motherhood/fatherhood, their marital dynamics and the transformations after the child’s birth.

Before the child’s birth

Before the birth of their child, Paula and César report that they used to go out a lot, were active and participated in a motorcycle group. Confirming this idea, Maria says “It’s just that routine thing really, which has changed. Let’s go out at night? Let’s go, at large, without giving explanations”(Maria, Couple - 2).

Celia and Renato confirm these ideas by pointing out that, before they had their daughter, the couple focused on their interests, were active and liked to travel.

These statements are in line with the results of the research by Ronchi and Avellar (2011), which pointed out that couples currently wish to perform other activities before getting into parenting, to enjoy their freedom, a reality the couples of the present study had also experienced.

On the other hand, Maria and Júlio say that, before the pregnancy, their dynamics were not very different, that what has changed were routine questions, which is more organized now, as expressed in: “I do not know if it is very different from what we are now, in fact, in terms of relationship level it is basically the same thing”(Júlio, Couple - 2).

It should be noted that, despite these changes pointed out by the spouses in the transition from conjugality to coparenting, this did not take the form of divergences and conflicts. This result supports the research by Menezes and Lopes (2007) and Lee and Doherty (2007), in which the results showed that high levels of marital quality in the transition to parenthood are essential to maintain satisfaction with the relationship despite the difficulties inherent in this process. Nevertheless, these dynamics should be established prior to the transition.

The couples in the present study already experienced good levels of marital satisfaction before the birth of their children, with conflicts inherent in any two-way relationship: “It was good, it was fighting, but it was good” (Roberto, Couple - 5). After that, conflicts are expected, but they do not significantly impact on marital satisfaction: “Every once in a while a small fight happens, but this is normal, but otherwise it is always well” (Marcos, Couple - 3).

After the birth of the child

In addition to not reporting high levels of conflict, couples report higher levels of satisfaction after the child’s birth. Paula and César say they are more united after the birth of their child, experiencing higher levels of marital satisfaction. Paula justifies that now they have to work together taking care of the son, as soon as they had the news of the pregnancy the union became more solid and her husband is more attentive to her, as she says:

“It’s because we have to work together, take care of him together, so I think we’re even more united, as soon as we found out that I was pregnant, and he started to pay more attention to me, right, takes care of me more, and woman like that, right, so I think it considerably enhanced the relationship. “(Paula, Couple - 1).

Maria and Júlio argue that their marital life is well, that whenever they can, they manage to go out and have fun: “Within the time that we can stay together, it’s okay, when possible the grandmothers are around, we can leave her to go for a walk and so” (Júlio, Couple - 2).

In the same sense, Célia and Renato say that, after their daughter was born, they have more tasks, but they feel satisfied with this new dynamic: “Look ... it is much more tumultuous, but it gives a feeling that it is complete” (Célia, Couple - 4). These data are in line with the study by Bossardi (2011) in that, the more satisfied with the marital relationship, the more the father engages in basic care for the children, which offers positive feedback for the marital and family dynamics.

On the other hand, Roberto indicates that the change was significant in the conjugality, especially the sexual life being restricted due to the lack of time and fatigue: “Wow, it was like, very intense, it was very intense, we had a very different life and today it’s when it’s possible, right, when it’s possible, when you’re not tired” (Roberto, Couple - 5).

Leticia and Marcos’ statements support the previous couple and describe that the sexual life after the daughter’s birth is “stopped”, because at times the daughter wakes up and needs care, as they report: “It’s kind of stopped, right love? We date when we can, and it is also difficult for us to go out “(Leticia, Couple - 3).

This transition period is significant in the family lifecycle because it generates changes in the image of the self, the other and the relationship. So the spouses who previously had their lives and desires now need to reorganize and establish new roles (Prati & Koller, 2011).

It is observed that couples reported significant changes in conjugality and, for some, this transformation appears more incisively, entailing further negative repercussions. That is so because it is the marital space that is more constrained, especially for these couples that chose to take longer to have children. They often spent significant time just the two of them. Hence, some couples resent spending less time as a couple, which is reflected in the sexuality, while others don’t. The coparenting seems to have approached the couple further, producing a feeling of union in the marital relationship (Soares, 2012; Matos & Magalhães, 2014).

Coparenting

This category covers issues related to sharing in childcare. Unlike the marital relationship, the coparenting relationship is triadic, as it involves the parental pair and the child, establishing a specific dynamic (Feinberg, 2003; Holland & McElwain, 2013; Jia & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2011).

Paula and César express that they divide the tasks related to the child, not overloading one or the other, as evidenced by the following statements:

“I feed him, he takes him, he burps, or he washes him and I make the bed, we are dividing this step well, so, not leaving everything on one side, if one sees that the other is tired, he takes the baby and takes care of, and goes to sleep, as he did when he arrived today, he saw and stayed with the baby and I went to sleep, so we are dividing” (Paula, Couple - 1).

Leticia and Marcos corroborate this discourse and say that they are dividing the tasks in relation to their daughter, according to the time each person has:

“It’s because like this, [...] ... he puts her clothes to wash and folds her clothes, sometimes I wash them, sometimes I fold them, he stays with her so I can take a shower, to eat, I stay with her, the only thing that I do is the part of the bath and change her, but the rest he participates “(Leticia, Couple - 3).

Célia and Renato also share the tasks in relation to their daughter, but they say they have done this since the beginning of the relationship, before the birth of their daughter: “If you come home and were unable to do the dishes, I’ll do it somehow, I’ll wait for Lara to sleep, I go there and get the job done “(Renato, Couple - 4). “It’s from the beginning, we always share everything, if I did not have time to bathe her he does so, easily” (Célia, Couple - 4).

Marie and Júlio say they do not have specific tasks, what is more specific is related to the night, which Maria is responsible for during the week, while Júlio takes care of their daughter at weekends:

“[...] Look, we do not have specific tasks of one or specific of the other, the only thing that we have more specific are the early mornings during the week because of my work, there [...] the early mornings during the week she takes care and, when the next day is not a working day, I give her a break, but the rest of the activities with her are well divided so, it’s actually who’s with her at that moment, so that one person is not responsible for everything”(Júlio, Couple - 2).

In relation to the tasks of picking up and taking the child or going to doctors, couples also have an organization that, in some cases, involves the extended family. In the case of Renato, who cannot take his daughter to school because he is working, Célia takes on this role and, when Renato is at home, he always picks p his daughter: “As for taking, he can’t, because he is working so it’s always me who takes her with the support of my father and my mother and, to pick her up, if he is at home he goes “(Célia, Couple - 4).

Roberto and Julia are very flexible, when one cannot pick up the child, the couple communicates. The couple Marcos and Leticia, in relation to taking and picking up their daughter at the grandmother’s, the two do this together.

As we can see, the couples show each other support in the tasks in relation to the child, with a division between the spouses. It is noteworthy that most of the coparenting issues reported by couples refer to tasks involving the children. This probably expresses the momentum of the lifecycle, with children still very small, without demand to express other coparenting dimensions. The literature indicates that coparental support between spouses is also expressed in higher levels of marital satisfaction and entails more significant repercussions than spouses who only divide domestic tasks, but not the tasks related to children (Piccinini et al., 2004; Beltrame & Botolli 2010). Thus, coparenting is very important, including the balance between paternal and maternal involvement, for the quality of this transition process.

Sharing of housework

This subcategory relates to how couples have divided the household chores after the birth of the child, emphasizing an egalitarian process. Paula says that César does a lot and already did so during the pregnancy, because she had already lost a baby, she had some limitations and her belly was already large, but whenever she could and can, she does the chores.

“When I was pregnant, I was not doing anything in here, he was doing everything, I did what I could, because my belly was very big and I had many limitations, but it really is divided” (Paula, Couple - 1) .

Marcos takes care of the food and is responsible for the couple’s dog, while Leticia takes care of the daughter and cleans the house:

“He washes dishes at night, he makes breakfast and I stay with her, he is responsible for his dog, and I stay with Rafa, cleaning the house like that, I do it, I sweep, I mob the floor, take off the dust, there is a person who helps, but in daily life we divide things” (Leticia, Couple - 3).

Célia and Renato also have the help of a domestic servant, but they report dividing the chores in their daily lives: “There is a girl who comes once a month who does the heavy cleaning really, but on a day-to-day basis it’s both of us “(Célia, Couple - 4).

Regarding the domestic chores, Maria and Júlio say that they also share well, that when one is responsible for Mariana, the other uses the opportunity to do some household chores: “Who is not with Mariana (laughs), usually we are dividing like this, I do more dishes and clothes, she does more mobbing and things like that, it is also a kind of rotation like this “(Júlio, Couple - 2).

Unlike the other couples, who have only some help with housework, Júlia and Roberto have full-time help. A nanny takes care of her daughter every day and also does household chores, and a domestic servant twice a week, who leaves everything organized, even the food, because Júlia says she does not know how to cook, as follows:

“Not to mention that I do not even know, I do not even know how to make food. Then she leaves food ready and I warm it up and serve the things, and I give her food ... So there’s not so much housework” (Júlia, Couple - 5).

It is identified that the men of some couples in this study engage equally in household tasks, as opposed to what some authors argue (Baxter et al., 2008; Hernandez & Hutz, 2010), who reported that, although the men are collaborating more in housework, women still dedicate themselves twice as much to take care of the children, wash and iron clothes, buy groceries, clean the house, etc. It is noteworthy, however, that the most recent of these studies is from 2010, inferring changes in these processes over time.

The greater participation of men in household tasks is a predictor of marital satisfaction (Lavee & Katz, 2002; Coltrane, 2000; Dessen & Braz, 2000), which can be associated with good levels of marital quality reported by the couples in this study, in addition to the good levels of coparenting experienced. On the other hand, some couples, when asked if some of the activities have already caused some conflict, affirmed that this was the case, coinciding with Vanalli & Barham (2012), in that women still feel that they contribute more than the men in the housework and report a burden.

Leticia says that conflicts have occurred, as she considers herself “quarrelsome” and wants things quickly and feels overwhelmed at times:

“It has already caused [conflict], we have already fought over the tasks, I am very quarrelsome, because I think he could help a little more or be more agile in the execution of the task. And I’m nervous, right, I want things for yesterday, and sometimes there is conflict about that, right? “(Leticia, Couple - 3).

The couple Célia and Renato say they have some conflicts, but that they solve them by talking. “Yes, there is always a comment, it’s always me who does that or kind of, you do a little and do not tell me to do it then! (Laughter) But we always talk later and settle things” (Célia, Couple - 4).

These reports show that women tend to demand that men do the tasks in their way and time, which can end up leading to conflict. In the couples in this study, however, these issues are discussed and solved, which according to Vanalli & Barham (2012) has a positive impact on the marital relationship. The following statements highlight this dynamic: “We communicate, one puts the table, the other goes there and cleans it” (Paula, Couple - 1). “I think nothing was that rehearsed in advance, things came up and it was kind of automatic, there are days when I’m super tired, when I am unable to do anything like that, and he totally supports me” (Célia, Couple - 4).

When asked how the spouses feel by assigning tasks to one another, they do not show difficulties and demonstrate satisfaction: “It is something easy for us” (Paula, Couple - 1).

It is identified that most of the men in this study showed to participate in household chores. For these couples, the division happened naturally and they do it to the extent that they have time. Despite causing small conflicts for some couples, there seems to be a relatively equalitarian division and they demonstrated satisfaction.

Dual - Career / Dual - Work

This category considers the careers of couples and the repercussions of the child’s birth, which started to require more flexibility to meet the demands. Some couples have jobs that entail significant demands and report this in the following statements:

“In my job, they demand a lot, they have a lot of work. So sometimes, if you are diffuse and end up not coping and forgetting the dates, deadlines and something that is important that should be done and you end up not doing it”(Leticia, Couple - 3).

“Mine is like, how can I say, there’s emotion and everything, because I work at the emergency, but I leave everything there, but something always ends up staying, when it ‘s a child it moves us” (César, Couple - 1). “Like, [..] ... I’m thinking about changing jobs, because I’m already close to retiring. I want something less stressful, more quiet that does not absorb me much. Because I want to have more time for the family too [... ] «(Renato, Couple - 4). «[... [ Ah, I have a bit more than 30 employees, right, so every day there is a problem, it›s a problem, it›s a ... I stress a lot» (Roberto, Couple - 5).

Some authors consider that all this burden of professional work can cause lack of energy or fatigue, influencing the motivation in other roles, such as the family and home (Aryee et al., 2005; Demerouti et al., 2005). According to the literature (Grzywacz et al., 2002), the balance between work and family life is still one of the greatest challenges in the life of dual-job or dual-career families. The following statements highlight these repercussions:

“In domestic activities, it exerts influence for me, because I feel discouraged, I do not have the courage sometimes to do the things I have to do, before Rafa, I would do things by myself, I would come home from work and do it, I would clean the house, sometimes he arrived from his course about 22h / 23h and I was still cleaning up and nowadays I no longer have that disposition to do so” (Leticia, Couple - 3).

“I think so, not so much the work of the hospital, but the caregiver, as I am one of the managers I have to spend much time on the cell phone, making weekly work scales, solving these last-minute unforeseen situations, sometimes this is very exhausting, my daughter wants attention. Pedro has also complained several times that I only stay on the phone, now I have policed myself more and when necessary I ask for more respect, right? “(Célia, Couple - 4).

It is noted in the previous statements that the arrival of the children changes the dynamics between the work and the household chores, as the care for the child is a priority. Tiredness causes the household chores, for example, to fall into the background.

In this context, support from the workplace can reduce stress and also serve to approximate the professional and family roles, promoting flexibility and support for this integration. The studies by Barnett (1998) and Jacobs and Gerson (2004) stress that perceiving the supervisor’s support in terms of family matters, even if informal, entails repercussions in reducing conflicts between the professional and the family, as we can see in the following statements.

“His is a lot quieter than mine in this sense, one day Lara got sick, and he had to stay home with her, because I could not, I have a dual journey, so his is more flexible than I in this sense “(Célia, Couple - 4).

In addition, it is identified that some couples, such as Júlio and Leticia, after maternity / paternity, have reduced their working hours, choosing no longer to bring work home, so they can spend more time with their child. This data evidences the findings of the research by Oliveira et al. (2011) in that, once financially stabilized and in a solid marital union, couples were able to choose to reduce their workload so as to be able to be closer to their children.

“For me, I had a lot more influence before Mariana was born, because it took me a lot longer to disconnect, after Mariana was born that reset lots of things for me in that sense, like[...]Now I get home and the key is already off, because she requires attention and also the part of liking to play with her” (Júlio, Couple - 2).

These results show that couples have a high weekly workload, and that some of them no longer bring chores home to increasingly dedicate themselves to their children, changing their relationship with work, so we identify that, although the work is exhausting, they are pleased to have flexibility, as mentioned earlier. Although professional practice is essential to the economic support of the family, family obligations are imposed, demanding flexibility to adapt.

Final considerations

The aim of this study was to understand the transition from conjugality to late coparenting in couples with dual careers, which we consider to have been achieved. We emphasize, however, that the findings need to be understood in view of the socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of the research sample.

In this context, the results indicate changes in marital and coparenting relationships. In particular, the parents in this study were significantly involved in the emotional and behavioral development of their children, a characteristic that used to be more attributed to women. In addition, they demonstrated participation that already started during the pregnancy and increased after birth, dividing the care for their children with their wives. This more egalitarian division of tasks concerning children and the home indicates the importance of high levels of coparenting, which are reflected in good marital quality indices. It is also important to point out that the fact that children are still small means that some dimensions of coparenting are not visible, which is likely to be expressed over the years, as a result of the educational demands and daily life of the tryad’s relationship.

In the transition from conjugality to coparenting, the couples in this study underwent changes in their routine. Before motherhood / fatherhood, they were more sexually and socially active, but this did not entail significant conflicts between them. On the other hand, different from the literature, some couples feel more satisfied in conjugality after the child’s birth, due to the sense of union promoted by the exercise of coparenting. It is noteworthy that the couples in this study have children under one year of age, a period of intense need for care, which may promote greater and coparental support.

The study participants’ high workload stands out, as well as the fact that most of them do not count on significant help, either from the extended family or from professionals, and yet did not report significant complaints of burden when having to reconcile careers and maternity / paternity. In this process, work flexibility, with the possibility of reducing the workload to spend more time with their children, was an expressive source of support.

This study may contribute to future intervention programs by referring to the importance of positive coparenting performance for marital quality and the development of the children. Finally, it is important to carry out more national studies on this phenomenon, such as quantitative studies, in order to map a larger number of couples.

Referências

Aryee, S., Srinivas, E., & Tan, H. (2005). Rhythms of life: antecedents and outcomes of work-family balance in employed parents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1) 132-146. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.132 [ Links ]

Barnett, R. (1998). Toward a review and reconceptualization of the work/family literature. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs, 124(2), 125-153. [ Links ]

Bauer, G., & Kneip, T. (2013). Fertility from a couple perspective: a test of competing decision rules on proceptive behaviour. European Sociological Review , 29(3), 153-548. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr095 [ Links ]

Baxter, J., Hewitt, B., & Haynes, M. (2008). Life course transitions and housework: Marriage, parenthood, and time on housework.Journal of Marriage and Family,70(2), 259-272. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00479.x [ Links ]

Beltrame, G. R., & Bottoli, C. (2010). Retratos do envolvimento paterno na atualidade.Barbaroi, 32(1), 205-226. doi:10.17058/barbaroi.v0i0.1380 [ Links ]

Bossardi, C. N. (2011). Relação do engajamento parental e conflito conjugal no investimento com os filhos. Florianópolis. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brasil. [ Links ]

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208-1233. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x [ Links ]

Cruz, Q. S., & Mosmann, C.P. (2015). Da conjugalidade à parentalidade: vivências em contexto de gestação planejada. Aletheia 47-48, 22-34. [ Links ]

Demerouti, E, Bakker, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2005). Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 67, 266-289. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.07.001 [ Links ]

Dessen, M. A., & Braz, M. P. (2000). Rede social de apoio durante transições familiares decorrentes do nascimento de filhos.Psicologia Teoria e Pesquisa, 16(3), 221-231. doi:10.1590/s0102-37722000000300005 [ Links ]

Dorsey, S., Forehand, R., & Brody, G. (2007). Coparenting conflict and parenting behavior in economically disadvantaged single parent African American families: The role of maternal psychological functioning.Journal of Family Violence, 22, 621-630. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9114-y [ Links ]

Feinberg, M. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting, 3, 85-131. doi:10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01 [ Links ]

Franco, M. (2005). Análise de conteúdo (2ª. ed.) Editora Líber Livro: Brasília [ Links ]

Grzywacz, J., Almeida, D., & McDonald, D. (2002). Work-family spillover and daily reports of work and family stress in the adult labor force. Family Relations, 47, 255-266. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00028.x [ Links ]

Heckler, V. I., & Mosmann, C. P. (2014). Casais de dupla carreira nos anos iniciais do casamento: Compreendendo a formação do casal, papéis, trabalho e projetos de vida.Barbarói, (41), 119-147. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/CaVBQk [ Links ]

Hernandez, J. A. E., & Hutz, C. S. (2010). Transição para a parentalidade: ajustamento conjugal e emocional.Psico,40(4), 414-421. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/6VABUx [ Links ]

Holland, A. S., & McElwain, N. L. (2013). Maternal and paternal perceptions of coparenting as a link between marital quality and the parent-toddler relationship. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 117-156. doi:10.1037/a0031427 [ Links ]

Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: work, family and gender inequality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Jia, R., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2011). Relations between coparenting and father involvement in families with preschool-age children. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 106-118. doi:10.1037/a0020802 [ Links ]

Lamela, D., Nunes-Costa, R., & Figueiredo, B. (2010). Modelos teóricos das relações coparentais: Revisão crítica.Psicol. Estud. , 15 ,205-216. doi:10.1590/S1413-73722010000100022 [ Links ]

Lavee, Y., & Katz, R. (2002). Divison of labor, perceived fairness, and marital quality: The effect of gender ideology.Journal of Marriage and Family ,64(1), 27-39. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00027.x [ Links ]

Lee, C. S., & Doherty, W. J. (2007). Marital satisfaction and fathers involvement during the transition to parenthood. Fathering, 5(2). Retrieved from http://goo.gl/ehmfkM [ Links ]

Matos, M. G., & Magalhães, A. S. (2014). Tornar-se pais: sobre a expectativa de jovens adultos.Pensando familias,18(1), 78-91. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/rz5KBP [ Links ]

McHale, J. P., & Rotman, T. (2007). Is seeing believing? Expectant parents’ outlooks on coparenting and later coparenting solidarity.Infant Behavior and Development,30(1), 63-81. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.007 [ Links ]

McHale, J., Khazan, I., Erera, P., Rotman, T., DeCourcey, W., & McConnell, M. (2002). Coparenting in diverse family systems. In Bornstein, M. (Ed.),Handbook of parenting (pp. 75-107). New Jersey: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Menezes, C. C., & Lopes, R. C. S. (2007). Relação conjugal na transição para a parentalidade: Gestação até dezoito meses do bebê. Psico USF, 12(1), 83-93. doi:10.1590/S1413-82712007000100010 [ Links ]

Minayo, M. C. S. (1994). O desafio do conhecimento: pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. (3a ed). São Paulo: Hucitec. [ Links ]

Morril, M. I., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Cordova, J. V. (2010). Pathways Between Marriage and Parenting for Wives and Husbands: The Role of Coparenting. Family Process, 49, 59-73. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01308.x [ Links ]

Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas em Transtorno do Desenvolvimento [NIEPED] (2006). Entrevista sobre coparentalidade. Porto Alegre: NIEPED - UFRGS. [ Links ]

Oliveira, R. B., Galdino, D. P., Cunha, C. V., & Paulino, E. D. F. R. (2011). Gravidez após os 35: uma visão de mulheres que viveram essa experiência.Corpus et Scientia, 7(2), 99-112. Recuperado de: http://goo.gl/dNbo1M [ Links ]

Piccinini, C. A., Gomes, A. G., Nardi, T. D., & Lopes, R. S. (2008). Gestação e a constituição da maternidade. Psico l. Estud., 13(1), 63-72. doi:10.1590/S1413-73722008000100008 [ Links ]

Piccinini, C. A., Silva, M. R., Gonçalves, T. R., Lopes, R. C. S., & Tudge, J. (2004). O envolvimento paterno durante a gestação. Psico l. Reflex. Crit. , 17(3), 303-314. doi:10.1590/s0102-79722004000300003 [ Links ]

Prati, L. E., & Koller, S. H. (2011). Relacionamento conjugal e transição para a coparentalidade: Perspectiva da Psico logia Positiva. Psico l. Clin. , 23(1),103-118. doi:10.1590/S0103-56652011000100007 [ Links ]

Ronchi, J. P., & Avellar, L. Z. (2011). Família e ciclo vital: a fase de aquisição. Psico l. Rev.,17(2), 211-225. doi:10.5752/P.1678-9563.2011v17n2p211 [ Links ]

Schupp, T.R. (2006). Gravidez após os 40 anos de idade: análise dos fatores prognósticos para resultados maternos e perinatais diversos. USP: São Paulo [ Links ]

Soares, D. A. M. (2012). Paternidade e Geratividade na Transição para a Parentalidade (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Centro Regional de Braga, Portugal. [ Links ]

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting , 10, 286-307. doi:10.1080/15295192.2010.492040 [ Links ]

Vanalli, A. C. G., & Barham, E. J. (2012). Após a licença maternidade: a percepção de professoras sobre a divisão das demandas familiares. Psico l. Soc. , 24(1), 130-138. doi:10.1590/S0102-71822012000100015 [ Links ]

Zavaschi, M. L., Costa, F., Brunstein, C., Kruter, B. C., & Estrella, C. G. (1999). Idade materna avançada: Experiência de uma boa interação. Rev. Psiquiatr. Rio Gd Sul, 21(1), 16-22. [ Links ]

Received: February 01, 2017; Revised: June 21, 2017; Accepted: August 09, 2017

texto em

texto em

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI