Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.10 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2016

ESTRÉS POST-TRAUMÁTICO Y ESTRÉS SUBJETIVO EN ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS TRAS ALUVIÓN DE BARRO

POST- TRAUMATIC STRESS AND SUBJECTIVE STRESS IN COLLEGE STUDENTS AFTER MUDSLIDE

Francisco Lería Dulčić

Jorge Salgado Roa

Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Atacama. Chile

Resumen: El estudio es de carácter preliminar y tiene como objetivo describir los niveles de sintomatología de estrés post-traumático y estrés subjetivo en una muestra de 149 estudiantes universitarios de Copiapó, Chile Se utilizó una estrategia asociativa de tipo comparativa transversal y un diseño de grupos naturales. Se aplicó una encuesta sociodemográfica breve y los instrumentos: Escala de Gravedad de Síntomas del Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (TEPT) y Escala de Impacto al Evento Revisada (EIE-R). Se observó que del total de la muestra el 2% presenta síntomas de estrés postraumático; el 85% presenta síntomas de mediana intensidad de impacto al evento y el 13.4% síntomas severos de estrés subjetivo. Se encontraron diferencias significativas en los puntajes de las escalas en función de la variable grado de impacto emocional, TEPT, F(4, 144) = 17.81, p < .001 y EIE-R F(4, 144) = 17.96; p < .001 y grado de pérdida material, TEPT, F(5, 143) = 3.20, p < .01 y EIE-R, F(5, 43) = 3.26; p < .01. No se encontraron diferencias en las puntuaciones en función del sexo. Los resultados sugieren la existencia de baja prevalencia de estrés postraumático.

Palabras Clave: desastres naturales; eventos ambientales traumáticos; estrés post-traumático; malestar emocional

Abstract: The preliminary study in nature aims to describe the levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms and subjective stress in a sample of 149 college students from Copiapó, Chile. A cross-comparative associate strategy with natural groups was used. A brief sociodemographic survey and two instruments were applied: Severity Scale Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Impact Event Scale Revised (EIE-R). Outof the total sample, reslts show that 2% have symptoms of post-traumatic stress; 85% have symptoms of medium impact intensity to the event and 13.4% have severe symptoms of subjective stress. Significant differences were found in the scores of the scales depending on the varying degree of emotional impact: PTSD, F(4, 144) = 17.81, p < .001 and IES-R, F(4, 144) = 17.96; p < .001; and grade of material loss: PTSD, F(5.143) = 3.20, p < .01 and IES-R, F(5.143) = 3.26; p < .01. No differences in scores were found according to gender. These results suggest low prevalence of PTSD.

Key Words: natural disaster; environmental traumatic event; post-traumatic stress; emotional distress

Recibido: 01/2016 Revisado: 04/2016 Aceptado: 07/2016

Correspondencia: Francisco Lería D., Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Atacama. Chile.

Correo Electrónico: francisco.leria@uda.cl

Introducción

Cada vez con más frecuencia es posible constatar el impacto que los cambios climáticos tienen en la población y sus infraestructuras, los cuales muchas veces por su carácter impredecible agravan sus efectos constituyéndose en un desafío para las autoridades. Tales cambios se originan debido a diversas causas y comprenden variados parámetros climáticos (temperatura, heladas, presión, vientos, lluvias, entre otros). En los últimos años se ha venido acuñando la expresión cambio climático antropogénico y/o peligro antrópico para señalar la influencia de la variable humana en su gestación (Oreskes, 2004; Rojas Vilches, & Martínez Reyes, 2011); y la denominación desastre socionatural para relevar el impacto que estos tienen en las personas (Villalba, 2012). La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) en su declaración constituida el año 2008, trató el tema del cambio climático global destacando la consideración de la amenaza directa que este representa para la salud (Chang, 2008 como se citó en Ochoa Zaldívar et al., 2015). Desde entonces se ha venido reconociendo la importancia de la investigación en desastres, existiendo una gran proliferación de estudios respecto de sus efectos en la salud mental (de la Barra, & Silva, 2010; Salcedo, 2014) y algunos de sus conceptos asociados como lo son la vulnerabilidad, la resiliencia y la gestión del riesgo (Aledi, & Sulaiman, 2014).

Una de las respuestas a eventos desastrosos que han sido objeto de amplio estudio han sido las reacciones de estrés, las cuales se sabe tienen un alto impacto en la salud mental. Sus efectos tienden a persistir en el tiempo adquiriendo muchas veces un carácter de cronicidad, técnicamente denominado estrés postraumático. La literatura especializada muestra cómo estas respuestas, junto a ser un fenómeno variable y dependiente del tipo de evento traumático, aumentan significativamente en casos de víctimas de catástrofes, desastres, emergencias naturales y/o socialmente inducidas (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011). Se ha afirmado que la naturaleza de estos eventos y su carácter repentino e intenso está asociada a una serie de respuestas sintomatológicas de estrés y finalmente a trastornos mentales, en los cuales la capacidad de funcionamiento diario del sujeto se ve altamente comprometida. El impacto psicológico a un evento catastrófico y su consecuente respuesta de estrés postraumático tiende a perdurar en el tiempo tanto en víctimas directas como indirectas (Samper, 2015); siendo su prevalencia estimada en la población mundial altamente variable entre un 4% hasta un 70%; específicamente en Chile desde un 4.4% a un 36% (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011; Pérez et al., 2009).

El Trastorno por Estrés Post-traumático (TEPT) es un tipo de trastorno de ansiedad caracterizado por la aparición de síntomas que siguen a la exposición a un evento estresante y que aparecen selectivamente cuando el sujeto se enfrenta a estímulos que recuerdan un aspecto del acontecimiento traumático, siendo tal la activación autonómica que produce una serie de dificultades tales como problemas del sueño, irritabilidad, dificultades para concentrarse, hipervigilancia, deterioro social y/o laboral, entre otras (American Psychiatric Association, 2002).

La investigación psicosocial en desastres ha estado inicialmente centrada en el impacto en la salud física y mental de las víctimas, para luego centrarse en el estudio del comportamiento de los grupos frente a eventos desastrosos en los cuales sus miembros se ven desbordados en los mecanismos habituales de afrontamiento (López-Ibor, Christodoulou, Maj, Sartorius, & Okasha, 2005). Estudios meta-analíticos clásicos como el de Rubonis y Bickman (1991), constataron que los síntomas ansioso-depresivos (e.g. consumo excesivo de bebidas alcohólicas), son de aparición más frecuente y mayor prevalencia. Estudios contemporáneos han enfatizado otras reacciones propias de la experiencia postraumática ante el desastre, como la falta de control y pérdida de confianza (Pineda Marín, & López-López, 2010). La característica de la respuesta postraumática varía y presenta elementos en común respecto del tipo de catástrofe. Por ejemplo, la exposición a terremotos está asociada a altos niveles de trastorno de estrés post-traumático (TEPT) como en el caso del ocurrido el 12 de mayo de 2008 en China, provincia de Sichuan, donde la prevalencia de TEPT a 18 meses fue de un 12.2% y 40.8% para síntomas depresivos (Zhiyong et al., 2012). En el terremoto de Haití ocurrido el 12 de enero del 2010, a 30 meses se observó una prevalencia de 36.75% para TEPT; 25.98% para síntomas depresivos en población de víctimas adultas (Cénat, & Derivois, 2014); y de 22.25% de TEPT en víctimas menores de edad (Cénat, & Derivois, 2015); destacando además cómo profesionales con experiencias previas en este tipo de situaciones (voluntarios y/o personal militar) obtienen puntajes superiores en la medición sintomatológica de TEPT (Guimaro, Santesso Caiuby, Pavão dos Santos, Lacerda, & Baxter Andreoli, 2013); hallazgo con antecedentes en la literatura científica (Soto, 2013). En una muestra de jóvenes a 9 meses de ocurrido el terremoto y explosión de la planta nuclear en Fukushima, Japón, el 11 de marzo del 2011, se observaron altos niveles de TEPT y comorbilidad con dolor menstrual y dismenorrea (Matsuoka et al., 2012; Takeda, Tadakawa, Koga, Nagase, & Yaegashi, 2013). En el continente europeo, luego del terremoto ocurrido en este caso en la ciudad de L’ Aquila en Abruzzo, Italia, el 6 de abril del 2009; se detectó sintomatología de TEPT y dificultades neuropsicológicas asociadas a la memoria retrógrada a 6 meses del evento, principalmente a causa del miedo persistente por las réplicas (Roncone et al., 2013).

En el caso de exposición a Tsunamis, como el ocurrido en el océano índico el año 2004, se ha encontrado una prevalencia de TEPT a 6 meses de entre 20 y 30%, destacando el miedo peritraumático, neuroticismo y bajos niveles de apoyo social como factores inductores de la respuesta de estrés postraumático (Hussain, Weisæth, & Heir, 2013).

Catástrofes por tormentas de nieve han sido también objeto de investigación, como la acaecida en China -provincia de Hunan- entre el 25 de enero y el 6 de febrero del 2008, con una prevalencia en jóvenes víctimas de un 14.5% para TEPT, concluyendo que los factores de riesgos más prominentes para el desarrollo del trastorno son: la distancia hogar-escuela, bajas estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés, neuroticismo y la presencia de apoyo emocional de su profesor (Daxing, Huifang, Shujing, & Ying, 2011).

En el caso de desastres por aluviones y avalanchas de agua y barro, como la causada por la erupción volcánica ocurrida el 12 y 13 de agosto de 1985 en Armero, Colombia, la depresión, ansiedad generalizada y TEPT fueron los 3 diagnósticos más frecuentes a 8 meses del desastre (Lima, Santacruz, Lozano, Luna, & Pai, 1988). Ante este tipo de catástrofe se ha visualizado a la hiperactivación autonómica como el síntoma de mayor prevalencia (Craparo, Faraci, Rotondo, & Gori, 2013). En otro estudio, en Taiwán, luego del tifón y aluvión Morakot -8 de agosto del 2009- se encontró un 25.8% de TEPT, particularmente representado por pensamientos intrusivos, hiperactivación fisiológica y psicológica y evitación (Cheng-Sheng et al., 2011). Un dato de especial preocupación es la alta prevalencia de TEPT (25.8%) encontrada ante este tipo de desastre, en jóvenes víctimas a 3 meses de un aluvión por el efecto de la sintomatología ansiosa de tipo irruptiva e intrusiva en el desarrollo cognitivo (Pinchen et al., 2011).

También se han desarrollado investigaciones en sobrevivientes de tornados, como el caso de Katrina -20 de agosto de 2005- en Estados Unidos, encontrándose una relación positiva entre la exposición directa a la catástrofe, la sintomatología de TEPT y la ocurrencia de episodios asmáticos (Arcaya, Lowe, Rhodes, Waters, & Subramanian, 2014).

No obstante, han sido los efectos traumáticos de post-guerra los más estudiados, existiendo solamente en la base PubMed 3961 resultados a enero del 2016. Estudios actuales se centran en 6 factores sintomatológicos frecuentes ante este tipo de experiencia traumática: la intrusión de pensamientos, la evitación, el afecto negativo, la anhedonia, la disforia y la excitación ansiosa (Konecky, Meyer, Kimbrel,& Morissette, 2015). Existen otras áreas interesantes de investigación al respecto, por ejemplo, los efectos en la población civil víctima de desastre por guerra y su visión y sentido relativo de la vida durante los procesos de reconstrucción social (Čorkalo, Ajdukovic, & Low, 2014).

A pesar de la unicidad de estos resultados y en relación a la alta prevalencia de TEPT en víctimas de catástrofes, ésta se ha mostrado altamente dependiente de la naturaleza y características del evento traumático, así como de las víctimas que lo experimentan. Por ejemplo, los efectos postraumáticos particulares de una catástrofe compleja como el terremoto y tsunami ocurrido en Chile -27 de febrero de 2010-, evidenciaron una prevalencia de TEPT muy superior a la esperada, entre 20% y 36% (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011). Finalmente, entre los factores de riesgo para la aparición de TEPT luego de la exposición a desastres se destacan: el bajo nivel educacional, el sexo de la víctima, la presencia premórbida de rasgos obsesivo-compulsivos, la presencia de emociones de aflicción y desespero, la posesión de hijos(as) bajo los 6 años de edad, el desplazamiento social a causa de las pérdidas materiales, la carencia de apoyo social posterior al evento, la ausencia de medidas precautorias frente a la posibilidad de un evento desastroso y los antecedentes premórbidos para el desarrollo de TEPT (Chen et al., 2014; Pollice, Bianchini, Roncone, & Casacchia, 2012). Otras variables moduladoras de la aparición y efecto postraumático son: sexo, género, nivel educativo, lesiones y/o mortandad en el tiempo de ocurrencia del evento desastroso (Grimm, Hulse, Preiss, & Schmidt, 2012). Por el contrario, existen factores comunes protectores dentro de los cuales se cuentan: la independencia social, iniciativa interpersonal, responsabilidad social y apertura social (Ling-Xiang, & Cody, 2011); la estabilidad emocional percibida (Hussain, Weisæth, & Heir, 2013) y la condición física (Momma et al., 2014).

De acuerdo a McFarlane y Norris (2006), los desastres pueden ser calificados de naturales (huracanes, terremotos, inundaciones) en oposición a desastres “humanos”, que a su vez pueden incluir desde accidentes no intencionales a acciones deliberadas (e.g. terrorismo). En la literatura especializada se ha enfatizado, sin embargo, que la exclusiva denominación desastre natural posee el riesgo de enmascarar el verdadero impacto de los factores sociales por sobre la acción de la naturaleza, siendo los primeros moduladores de la experiencia de estrés vivida por los sujetos víctimas. Según Cova y Rincón (2010), estas distinciones han sido cuestionadas, señalando que si bien en algunos desastres el factor gatillador central es un evento natural en gran medida incontrolable, sus implicaciones y efectos son derivados de la acción humana. Un ejemplo de ello son los estudios meta-analíticos, que han mostrado la variabilidad del impacto en la salud mental en los miembros de las comunidades víctimas de una catástrofe, provenientes de países de menor desarrollo económico (Norris, & Elrod, 2006).

Actualmente se utiliza el concepto desastre socionatural para integrar las variables que intervienen en la producción de eventos desastrosos, junto a los aspectos moduladores de la experiencia traumática de la víctima. Además, se busca precisar “las responsabilidades de los distintos actores y lograr que gobiernos, organismos multilaterales y organizaciones no gubernamentales contribuyan a reducir riesgos, a evitar eventos, disminuir impactos” (Villalba, 2012). Por otra parte, el estudio de los modelos de intervención en desastres y emergencias descubren que el impacto psicosocial de un evento desastroso está vinculado en gran medida a la deficiente preparación que las comunidades y los gobiernos tienen (Osorio Yepes, & Díaz Facio Lince, 2012). Considerando lo anterior, la delimitación de un factor sociocultural es esencial a la hora de evaluar los reales efectos de una catástrofe y pueden ser medidos por el impacto que estos tienen en la sociedad que lo experimenta, Según Arnold-Cathalifaud (2010), en el caso de Chile y el desastre ocurrido el 27 de febrero de 2010 (27 F), con su “movimiento sísmico y con todas sus réplicas juntas, es menor que el terremoto social ocurrido en el país” (p. 41). El autor agrega: “nadie puede ser culpable del terremoto o del maremoto en tanto fenómenos naturales, pero sí pueden imputarse responsabilidades por una mala preparación para afrontarlos, por malas construcciones, malos diseños de hospitales o aeropuertos”. Otros estudios han enfatizado que el impacto de una catástrofe pasa de ser inicialmente un evento natural a uno socio-natural, mostrando cómo el accionar del Estado incurre en una serie de intervenciones que son percibidas por la población como agravantes al desastre natural mismo (Ugarte, & Salgado, 2014). Un ejemplo de ello es cómo el factor humano se puede constituir en un elemento agravante frente a eventos fortuitos y/o inesperados, por ejemplo, en el caso del desastre ocurrido en Estonia -28 de septiembre de 1994- cuando un ferry de pasajeros se hundió dejando a 852 personas fallecidas y solamente 137 rescatadas, luego de varias horas de flotación en condiciones meteorológicas adversas. En este estudio se evaluó a los sobrevivientes luego de tres meses, uno, tres y catorce años después de la catástrofe, encontrando un 27% de prevalencia de estrés postraumático (Arnberg, Eriksson, Hultman, & Lundin, 2011). En el caso de Chile, existen estudios que han caracterizado la prevalencia y gravedad de síntomas del TEPT en personas afectadas por la dictadura militar ocurrida entre los años 1973 y 1990, revelando una mayor presencia de sintomatología ansiosa en mujeres y personas que no tenían una participación política al momento de la represión, registrando más síntomas de tipo evitativo (Moscoso, 2013).

El impacto de un desastre no depende solo de la exposición directa al evento estresante (terremoto, alud, incendio, etc.), sino también de las pérdidas, daños y sentimientos de amenaza que se generan sobre las personas y su entorno inmediato, así como las consecuencias de mediano y largo alcance (Félix, & Rincón, 2010). Estas consecuencias tienden a manifestarse particularmente en cada sujeto y/o grupo víctima, generándose un efecto particular y selectivo en contraposición a una reacción global de estrés indiferenciada. Por ejemplo, el citado terremoto y tsunami ocurrido en el sur de Chile (27 F) generó, en un grupo de trabajadores, altos niveles de estrés sin una disminución de su satisfacción laboral (Jiménez, & Cubillos, 2010). Finalmente, existe evidencia acerca del impacto del tratamiento individual con víctimas de catástrofes (Figueroa, Marín, & González, 2010; Zhang, Feng, Xie, Xu, & Chen, 2011), así como la efectividad de programas de orientación psicosocial en el mejoramiento de las estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés (Bianchinia, et al., 2013). Osorio Yepes y Díaz Facio Lince (2012) citan 30 modelos y experiencias documentadas de intervención psicosocial en situaciones de desastre en España y Latinoamérica. Estas investigaciones han mostrado que la latencia de la intervención (e. g. rescate o abastecimiento de primera necesidad), la presencia de abundante ayuda material, los espacios de ayuda psicosocial post-evento y la especial atención a grupos de alto riesgo, juegan un papel central en la rehabilitación de las víctimas de desastres y emergencias (Chen et al., 2014).

El 25 de marzo del 2015 se precipitó en las regiones chilenas de Antofagasta, Atacama y Coquimbo el mayor desastre pluviométrico en 80 años. El evento provocó fuertes precipitaciones en un corto período de tiempo con el consecuente desborde de los ríos Copiapó y El Salado y el deslizamiento de tierras, en gran parte provenientes de los relaves de la minería situados alrededor de la ciudad (27° 21′ 59″ S, 70° 19′ 59″ W). Como consecuencia fueron cortadas o aisladas varias rutas, viviendas destruidas, cortes de energía eléctrica y fibra óptica, entre otros estragos. El gobierno decretó zona de catástrofe y luego zona de excepción constitucional, razón por la cual unos mil militares se hicieron cargo del resguardo del orden público y de las tareas de ayuda de las áreas damnificadas (“Mil militares resguardan Atacama”, 2015).

La población fue expuesta a una serie de eventos estresantes durante al menos 10 días luego de ocurrida la catástrofe, principalmente por cortes de luz y agua; detención total del tránsito en muchos de los sectores de la ciudad y el no funcionamiento de los servicios básicos. Además, se observó una importante alza de precios en bienes de primera necesidad e intentos de saqueos (Gutiérrez, 2015). Los datos oficiales cuentan más de 28.000 víctimas, 31 personas fallecidas, 16 desaparecidas y 16.588 daminficados (Ministerio de Interior y Seguridad Pública, 2015). Además, se estableció la existencia de un 43% de viviendas con daños reparables, un 23% daños leves, un 13% moderados, un 7% mayores y un 6% no reparables (Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 2015). La ciudad se vio además altamente sectorizada, por ejemplo, los callejones de la ciudad fueron inundados casi por completo, a diferencia de los sectores altos. Además, luego de transcurrido algún tiempo, la ciudad se vio afectada por contaminación del aire, daños en la vía pública y peatonales, basura y montones de barro apilados en distintos sectores de la ciudad, entre otros efectos y residuos del aluvión, situación que plantea la permanencia de factores de estrés que prolongan el impacto de la catástrofe en el tiempo.

Considerando los antecedentes expuestos, las preguntas que guían el presente estudio son las siguientes; 1) ¿Cuáles son los niveles de sintomatología de estrés post-traumático y de estrés subjetivo posterior al aluvión?;

2) ¿Qué factores sociodemográficos determinan la variabilidad de las escalas TEPT y EIE-R?; 3) ¿El grado de impacto emocional y la pérdida material determinan la variabilidad de los resultados en las escalas TEPT y EIE-R?

El objetivo ha sido identificar los niveles de sintomatología de estrés post-traumático y de estrés subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios posteriores al aluvión y determinar los factores que establecen su variabilidad.

Materiales y método

Diseño de investigación

El estudio corresponde a una investigación empírica, se utilizó una estrategia asociativa de tipo comparativa transversal y un diseño de grupos naturales, no se manipulan variables y se analizan las relaciones de estas indagando las diferencias entre dos o más grupos de individuos a partir de los contrastes generados por la naturaleza y la sociedad (Ato, López, & Benavente, 2013).

Participantes

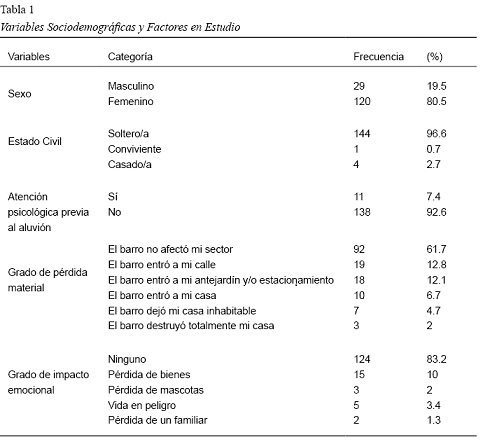

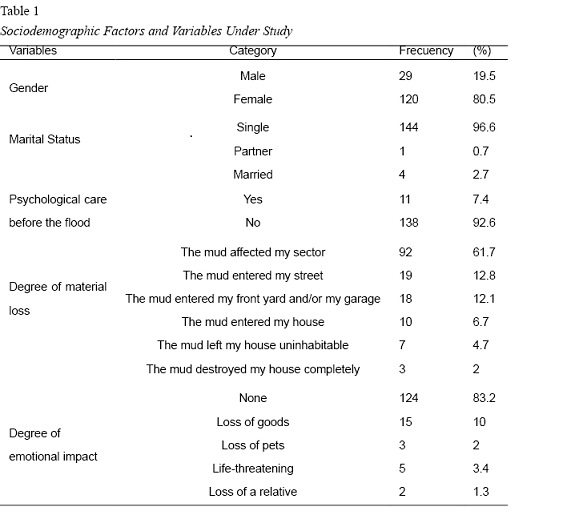

Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico intencional o por conveniencia. Participaron 149 estudiantes universitarios de la comuna de Copiapó, quienes fueron seleccionados por cursar carreras que se dictaban en un Campus universitario afectado severamente por el aluvión y que presentaba dificultades de acceso y de normal funcionamiento durante los meses posteriores al desastre. En cuanto a las características de la muestra, el 19.5% de los encuestados, corresponde al género masculino y el 80.5% al género femenino; con edades entre 17 y 25 años (M = 19.71 y DE = 3.22), en su mayoría (96.6%) solteros/as. Además, el 38.3% informa de haber sido afectado por el barro en distintos niveles de severidad y el 16.7% informa de impacto emocional con distintos niveles de intensidad (ver tabla 1).

Instrumentos

- Escala de Gravedad de Síntomas del Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (Echeburúa, Corral, Amor, Zubizarreta, & Sarasua, 1997a). Corresponde a una escala de evaluación de síntomas de TEPT según los criterios del Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales (DSM-IV, 2002). Se presenta en formato tipo Likert (0 = Nada hasta 3 = 5 o más veces por semana) que incluye 17 reactivos agrupados en tres dimensiones (Reexperimentación intrusiva, Evitación y Activación). Cuenta además con una subescala complementaria de Manifestaciones Somáticas. Ha sido validada en España con víctimas de agresión sexual y violencia intrafamiliar, presentando altos niveles de fiabilidad a través de su estabilidad temporal y consistencia interna (Alfa de 0.89 y 0.92 respectivamente), lo cual demuestra ser un instrumento que sobrepasa las exigencias mínimas para ser utilizado en contextos de investigación, clínicos y/o jurídico-forenses, ha sido usado en diversas investigaciones en el área (Blasco-Ros, Sánchez-Lorente, & Martínez, 2010; Echeburúa, Corral, Amor, Sarasua, & Zubizarreta, 1997b; Echeburúa, Corral, & Amor, 2003). Fue aplicada en Chile por Moscoso (2013) a personas afectadas por terrorismo de Estado, obteniendo coeficientes Alfa satisfactorios en todas las dimensiones (entre .86 y .94) y un Alfa de .96 para el resultado global, lo que indica alta consistencia interna y un nivel de fiabilidad satisfactorio. El cuestionario presentó una adecuada validez discriminante de los criterios diagnósticos de estrés post-traumático, a diferencia de otros cuadros ansiosos.

- Escala de Impacto al Evento Revisada (IES - Impact of Event Scale de Weiss, & Marmar, 1997) validada en España por Baguena et al. (2001). Este es un instrumento que posee 22 ítems y 3 subescalas (Intrusión, Evitación e Hiperactivación) con formato tipo Likert para la evaluación de la intensidad de la sintomatología (desde 0 = Nada hasta 4 = Extremadamente). Permite obtener a partir de la puntuación global la severidad del malestar emocional o estrés subjetivo (Costa Requena, & Gil Moncayo, 2012). El instrumento se ha utilizado en diversas investigaciones respecto del impacto a desastres y emergencias (Arcaya et al., 2014; Brunet, St-Hilaire, Jehel, & King, 2003; Caamaño, González, & Sepúlveda, 2011; Creamer, Bell, & Failla, 2003; Giorgi et al., 2015; Morina, Ehring, & Priebe, 2014; Warsini, Buettner, Mills, West, & Usher, 2015). incluyendo aluviones de barro (Cheng-Sheng, et al., 2011; Craparo et al., 2013); sus propiedades psicométricas han sido evaluadas en China arrojando valores adecuados (Wu, & Chan, 2004). Además presenta un 72% de sensibilidad para la detección de TEPT en relación a otros instrumentos psicométricos similares (Mouthaan, Sijbrandij, Reitsma, Gersons, & Olff, 2014). La EIE-R fue adaptada y validada para población chilena por Caamaño et al., (2011) concluyendo que es una medida confiable de autoreporte y adecuada validez.

- Encuesta sociodemográfica: construída por los autores para recolectar información referente a edad, sexo, carrera universitaria, estado civil, lugar de residencia, lugar donde se encontraba el día del aluvión, grado de pérdida material (consta de 6 niveles, 1 = El barro no afecto mi sector; 6 = El barro destruyó totalmente mi casa) y grado de impacto emocional informado (5 niveles, 0 = Ninguno; 4 = Perdida/muerte de un familiar), siendo estas de carácter nominal y ordinal a excepción de la edad del sujeto.

Procedimiento

Los instrumentos fueron aplicados en los tres meses posteriores al aluvión de barro, previa aprobación por un comité de idoneidad científica de la institución de los autores que acredito los aspectos éticos del estudio. Una vez comunicados a los participantes los objetivos, se procedió a entregar un protocolo con las dos escalas, el cuestionario sociodemográfico y un consentimiento informado, que debía ser devuelto en sobre sellado para garantizar la confidencialidad de los datos.

Las diferencias se estimaron utilizando el análisis de varianza (ANOVA) de un factor en función de las variables sociodemográficas y las categorías de grado de pérdida material e impacto emocional. Para el sexo se utilizó la prueba t de Student, para muestras independientes. Se determinó la homogeneidad de varianzas con la prueba de Levene, en el caso de no existir se aplicó el test de Welch (Armitaje, Berry, & Matthews, 1994). Las comparaciones post-hoc se realizaron aplicando la prueba de Tukey. Se utilizó como medida del tamaño del efecto la d de Cohen y Eta parcial al cuadrado (ηp2) (Cohen, 1988). Se realizaron regresiones lineales utilizando el método por pasos.

Resultados

A continuación, se presentan los principales resultados obtenidos en el estudio, siendo estos de carácter preliminar.

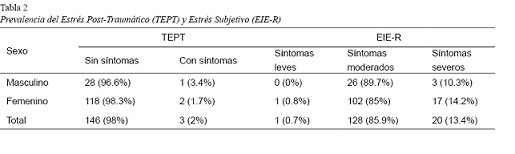

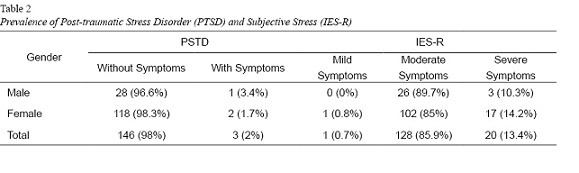

El análisis respecto de la prevalencia de síntomas de estrés postraumático muestra que 146 participantes (98%) no presentan síntomas de estrés postraumático y 3 sujetos (2%) presentan la sintomatología arrojada por la Escala de Gravedad de Síntomas del Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (TEPT). Según la EIE-R, 20 estudiantes (13.4%) presentan síntomas severos de estrés subjetivo o malestar emocional (ver tabla 2).

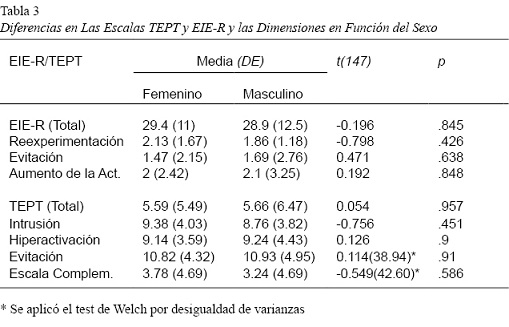

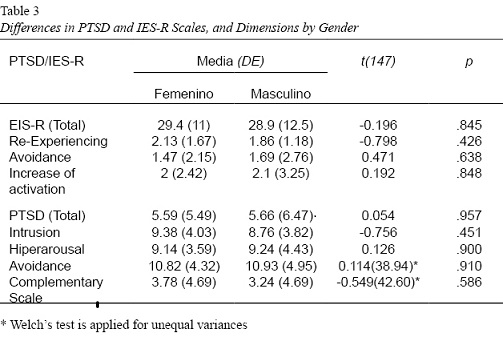

Profundizando en el análisis y siguiendo las preguntas de investigación, no se encontraron diferencias significativas de medias entre hombres y mujeres respecto de la sintomatología de estrés postraumático y estrés subjetivo (ver tabla 3).

En relación a la variabilidad de la sintomatología de estrés postraumático y el estrés subjetivo, se procedió a comparar los resultados de las escalas totales y las dimensiones del EIE-R y TEPT en función de las variables sociodemográficas estado civil y carrera universitaria y las categorías de gradación del “grado de impacto emocional” y “grado de pérdida material”.

Como se muestra en la tabla 4, no se encontraron diferencias significativas en la sintomatología de estrés postraumático y estrés subjetivo en función del estado civil y la carrera universitaria.

Se encontró homogeneidad de varianzas en las categorías de “grado de pérdida material” respecto del estrés subjetivo (EIE-R) y la sintomatología de estrés postraumático (TEPT) arrojando el estadístico de Levene valores de 1.70 (p = .137) y 1.41 (p = .221) respectivamente. Se hallaron diferencias significativas de medias en la EIE-R y sus dimensiones (Reexperimentación y Aumento de la Activación) en función del grado de perdida material a excepción de Evitación, F(5. 143) = 2.166 , p > .05. Además, se observa que el tamaño del efecto de las diferencias en el EIE-R y la dimensión de Reexperimentación es moderado/alto (valores de ηp2 entre 0.10 y 0.14) (Cohen, 1988). También se encontraron diferencias significativas en el TEPT y todas sus dimensiones (Intrusión, Hiperactivación y Evitación) en función del grado de perdida material y el tamaño del efecto es de moderado/alto (valores de ηp2 entre 0.06 y 0.14). La prueba post hoc HDS Tukey no logró diferenciar los grupos.

Para la variable “grado de impacto emocional” existe homogeneidad de varianzas respecto del estrés subjetivo (EIE-R) y la sintomatología de estrés postraumático (TEPT), arrojando el estadístico de Levene valores de 2.202 (p = .06) y 1.372 (p = .06) respectivamente. Se encontraron diferencias significativas en las puntuaciones del EIE-R y todas sus dimensiones en función del grado de impacto emocional. Se observa que el tamaño del efecto es alto (valores de ηp2 entre 0.19 y 0.31) (Cohen, 1988). También se presentan diferencias significativas en el TEPT y todas sus dimensiones en función del grado de impacto emocional y el tamaño del efecto de las diferencias igual es significativo (valores de ηp2 entre 0.22 y 0.32).

La prueba post hoc HDS Tukey reveló que las diferencias se producen entre la categoría “vida en peligro” y los otros cuatro grupos respecto a los síntomas de estrés postraumático (p < .05) y de estrés subjetivo (p < .001).

Se realizó un análisis de regresión lineal múltiple con los puntajes obtenidos en las escalas TEPT y EIE-R considerando la edad, el grado de pérdida material y el grado de impacto emocional. La variable que entró en el modelo fue el grado de impacto emocional que predice el 21.3% de la varianza de los puntajes obtenidos en el TEPT (R2 = .213). siendo significativo, F(1.147) = 39.90, p = .000,

β = 0.462, p = .000, 95% IC[.374, .549]. También predice el 16.8% de la varianza de los puntajes obtenidos en el EIE-R (R2 = .168), siendo igualmente significativo, F(1.147) = 29.731, p = .000, β = 0.410, p = .000, 95% [0.376, 0.805]. En los dos casos el aporte de la variable grado de perdida material fue menor.

Discusión y conclusiones

El estudio tuvo como objetivo identificar los niveles de sintomatología de estrés post-traumático y de estrés subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios posteriores al aluvión y determinar los factores que establecen su variabilidad. Los factores evaluados fueron de tipo sociodemográfico y las categorías de impacto emocional y pérdida material.

Según los resultados preliminares, no se encontraron porcentajes significativos de presencia de sintomatología de estrés postraumático (2%), ni de estrés subjetivo (13.4%), lo que se relaciona con los datos registrados en Chile que van desde un 4.4% a un 36% (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011; Pérez et al., 2009). Por otra parte, se presenta un porcentaje mayor en los síntomas moderados de estrés subjetivo (85.9%), lo que sugiere la presencia perdurable del impacto psicológico tanto en víctimas directas como indirectas (Samper Lucerna, 2015). Así también, se confirma lo acotado por Arnold-Cathalifaud (2010) quien afirma que el impacto psicológico a un desastre no se encuentra limitado a los sujetos que se ven directamente afectados.

Con respecto a las variables sociodemográficas como sexo, estado civil y carrera cursada, no se presentan diferencias en las escalas de estrés postraumático y el estrés subjetivo, siendo posible asociar que la mayoría de los estudiantes universitarios eran solteros (96.6%) y que podría relacionarse con independencia social (Ling-Xiang, & Cody, 2011) y estabilidad emocional percibida (Hussain, Weisæth, & Heir, 2013). Así también, el nivel educativo de los participantes se constituiría en un factor protector en la aparición y efecto del estrés (Grimm, Hulse, Preiss, & Schmidt, 2012).

La variabilidad en los resultados obtenidos con las escalas de sintomatología de estrés postraumático y estrés subjetivo se presentan en función de las variables “grado de impacto emocional” y “grado de pérdida material”, siendo la primera la que provoca mayor variabilidad. Respecto de lo señalado por el Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (2015) un 6% de las viviendas presentan daños no reparables que requieren ser reconstruidas posterior al aluvión, y la información entregada por el Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública (2015) da cuenta de un total de 31 personas fallecidas y 16 desaparecidas, lo que se relaciona con las categorías de “vida en peligro” y “el barro destruyó completamente mi casa”, que figuran con la gradación de mayor severidad del grado de impacto emocional y de perdida material respectivamente. Cerca del 25.5% de los participantes fue afectado por el ingreso del barro al antejardín y/o estacionamiento mientras que el 13.4% fue dañado por el ingreso del barro a sus casas. El 6.7% informa de un mayor impacto emocional, sin embargo, no atribuye gran intensidad a la perdida de bienes. De esta forma, se sostiene lo planteado por Arnold-Cathalifaud (2010) respecto del impacto psicológico y la vivencia directa del evento, siendo esta última la que generaría TEPT altas y explicaría las diferencias encontradas en el presente estudio con la literatura que plantea niveles significativos de TEPT en personas expuestas a terremotos (Cénat & Derivois, 2014; Guimaro et al., 2013; Leiva-Bianchi, 2011; Matsuoka et al., 2012; Roncone et al., 2013; Takeda et al., 2013; Zhiyong et al., 2012;); tsunamis (Hussain et al., 2013); tormentas de nieve (Daxing et al., 2011); tifón y aluvión (Cheng-Sheng et al., 2011) y tornados (Arcaya et al., 2014).

Con relación a lo anterior, la severidad en la sintomatología de estrés postraumático y estrés subjetivo está determinada por el tipo de desastre, siendo el TEPT mayor en los afectados por terremotos (sobre el 12.2%) que, por aluviones, donde la Hiperactivación autonómica es el síntoma de mayor prevalencia (Craparo et al., 2013).

Los datos proporcionados por el Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2015) señalan que la ciudad ha mostrado en el tiempo altos índices en la percepción de problemas sociales y ambientales en relación a la contaminación, higiene y falta de infraestructura comunitaria; todos factores que afectan la calidad de vida de los habitantes. Por último, considerando que las variables emocionales, tales como la felicidad subjetiva, estrés percibido, gestión de las emociones, entre otras, tienen un impacto en el desempeño académico (Ferragut, & Fierro, 2012; Peña-Sarrionandia, Mikolajczak, & Gross, 2015), sería interesante conocer si la presencia de sintomatología de estrés subjetivo de mediana intensidad encontrada en los participantes afectó su desempeño académico. Por último, es conveniente señalar que, al tratarse de un estudio de prevalencia de tipo preliminar, queda pendiente la realización de otros análisis estadísticos, como por ejemplo pruebas de residuos, chi cuadrado y regresión logística multivariada, entre otras. Además, incorporar a la muestra otros sectores de la población que fueron afectados directa e indirectamente por el aluvión, para lograr precisar y extender los alcances de este estudio. Actualmente se están desarrollando los análisis mencionados bajo el proyecto “Impacto en el bienestar subjetivo, calidad de vida y visión de mundo a un año de la exposición a una catástrofe socionatural”, financiado por la Universidad de Atacama, Chile.

Referencias

Aledi, Antonio, & Sulaiman, Samia. (2014). La incuestionabilidad del riesgo. Ambiente & Sociedade, 17(4), 9-16. doi:10.1590/1809-4422ASOCEx01V1742014

American Psychiatric Association. (2002). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales, DSM-IV-TR. Barcelona: Masson.

Arcaya, M.C., Lowe, S. R., Rhodes, J. E., Waters, M. C., & Subramanian, S. (2014). Association of PTSD Symptoms with Asthma Attacks among Hurricane Katrina Survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 725–729. doi:10.1002/jts.21976

Arnberg, F.K., Eriksson, N.G., Hultman, C.M., & Lundin, T. (2011). Traumatic Bereavement, Acute Dissociation, and Posttraumatic Stress: 14 Years after the MS Estonia Disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(2) 183–190. doi:10.1002/jts.20629

Arnold-Cathalifaud, M. (2010). Catástrofes naturales y sociedad. Revista Chilena de Salud Pública, 14(1), 40-42.

Ato, M., López, J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología, 29(3),1038-1059. doi:10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Bianchinia, V., Ronconea, R., Tomassinia, A., Necozione, S., Cifone, M., Casacchiaa, M., & Pollicea, R. (2013). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Young People after L’Aquila Earthquake. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 9, 238-242. doi:10.2174/1745017901309010238

Blasco-Ros, C., Sánchez-Lorente, S., & Martínez, M. (2010). Recovery from depressive symptoms, state anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in women exposed to physical and psychological, but not to psychological intimate partner violence alone: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 98. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-98

Brunet, A., St-Hilaire, A., Jehel, L., & King, S. (2003). Validation of a French version of the impact of event scale-revised. Canadian Jourmal of Psychiatry, 48(1), 56-61.

Caamaño, L., González, L., & Sepúlveda, M. (2011). Adaptación y validación de la versión chilena de la escala de impacto de evento-revisada (EIE-R). Revista Médica de Chile 139, 1163-1168. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872011000900008

Cénat, J. M., & Derivois, D. (2015). Long-term outcomes among child and adolescent survivors of the 2010 Haitian earthquake. Depression and anxiety, 32(1), 57-63. doi:10.1002/da.22275

Cénat, J. M., & Derivois, D. (2014). Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in adults survivors of earthquake in Haiti after 30 months. Journal of Affective Disorders, 159, 111-117. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.025

Chen, H., Chen, Y., Au, M., Feng, L., Chen, Q., Guo, H., Li, Y., & Yang, X. (2014). The presence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in earthquake survivors one month after a mudslide in southwest China. Nursing and Health Sciences, 16, 39–45. doi:10.1111/nhs.12127

Cheng-Sheng, C., Chung-Ping, C., Cheng-Fang, Y., Tze-Chun, T., Pinchen, Y., Rei-Cheng,…Hsin-Su, Y. (2011). Validation of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised for adolescents experiencing the floods and mudslides. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 27, 560-565. doi:10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.033

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Čorkalo, D.B., Ajduković, D., & Löw Stanic, A. (2014). When the world collapses: changed worldview and social reconstruction in a traumatized community. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, 1-6. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v5.24098

Costa Requena, G., & Gil Moncayo, F. (2012). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala revisada del impacto del evento estresante (IES-R) en una muestra española de pacientes con cáncer. Análisis y Modificación De Conducta, 33(149). Recuperado de http://www.uhu.es/publicaciones/ojs/index.php/amc/article/view/1218

Cova, F., & Rincón, P. (2010). El Terremoto y Tsunami del 27-F y sus Efectos en la Salud Mental. Terapia psicológica, 28(2), 179-185. doi:10.4067/S0718-48082010000200006

Craparo, G., Faraci, P., Rotondo, G., & Gori, A. (2013). The Impact of Event Scale – Revised: psychometric properties of the Italian version in a sample of flood victims. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 1427–1432. doi:10.2147/NDT.S51793

Creamer, M., Bell, R., & Failla, S. (2003). Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale Revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 1489–1496. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010

Daxing, W., Huifang, Y., Shujing, X., & Ying, Z. (2011). Risk factors for posttraumatic stress reactions among Chinese students following exposure to a snowstorm disaster. BMC Public Health, 11(96), 1-7. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-96

de la Barra, Flora, & Silva, Hernán. (2010). Desastres y salud mental. Revista chilena de neuro-psiquiatría,48(1), 7-10. doi:10.4067/S0717-92272010000200001

Echeburúa, E., Corral, P. D., Amor, P. J., Zubizarreta, I., & Sarasua, B. (1997a). Escala de gravedad de síntomas del trastorno de estrés postraumático: propiedades psicométricas. Análisis y modificación de conducta, 23(90), 503-526.

Echeburúa, E., Corral, P. Amor, P.J., Sarasua, B., & Zubizarreta, I. (1997b). Repercusiones psicopatológicas de la violencia doméstica en la mujer: un estudio descriptivo. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 2, 7-19.

Echeburúa, E. Corral, P., & Amor, P.J. (2003). Evaluation of psychological harm in the victims of violent crime. Psychology in Spain, 7, 10-18.

Ferragut, M.& Fierro, A. (2012). Inteligencia emocional, bienestar personal y rendimiento académico en preadolescentes. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 44(3), 95-104

Félix, C., & Rincón, P. (2010). El Terremoto y Tsunami del 27-F y sus Efectos en la Salud Mental. Terapia Psicológica, 28(2), 179-185. doi:10.4067/S0718-48082010000200006

Figueroa, R.A., Marín, H., & González, M. (2010). Apoyo psicológico en desastres: Propuesta de un modelo de atención basado en revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Revista médica de Chile, 138, 143-151.

Giorgi, G., Fiz Pérez, F.S., Castiello, A., D’Antonio, A.C., Mucci, N., Ferrero, C. ... Arcangeli, G. (2015). Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale-6 in a sample of victims of bank robbery. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 8, 99-104. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S73901

Grimm, A., Hulse, L., Preiss, M., & Schmidt, S. (2012). Post- and peritraumatic stress in disaster survivors: an explorative study about the influence of individual and event characteristics across different types of disasters. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(7382) 1-9. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.7382

Guimaro, M., Santesso Caiuby, A., Pavão dos Santos, O., Lacerda, S., & Baxter Andreoli, S. (2013). Sintomas de estresse pós-traumático em profissionais durante ajuda humanitária no Haiti, após o terremoto de 2010. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 18(11), 3175-3181. doi:10.1590/S1413-81232013001100008

Gutiérrez, P. (26 de marzo de 2015). Catástrofe en el norte. La nación. Recuperado de http://www.lanacion.cl/noticias/regiones/catastrofe-en-el-norte/denuncian-que-bidones-de-agua-se-venden-a-15-mil-en copiapo/2015-03-26/123315.html

Hussain, A., Weisæth, L., & Heir, T. (2013). Posttraumatic stress and symptom improvement in Norwegian tourists exposed to the 2004 tsunami – a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 13(232), 1-11. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-232

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2015). Encuesta nacional de calidad de vida y salud. Recuperado de http://www.ine.cl/canales/chile_estadistico/calidad_de_vida_y_salud/calidadvida/final3region. pdf

Jiménez, A.E., & Cubillos, R.A. (2010). Estrés percibido y satisfacción laboral después del terremoto ocurrido el 27 de febrero de 2010 en la zona centro-sur de Chile. Terapia Psicológica, 28, 191-196. doi:10.4067/S0718-48082010000200007

Meyer, E.C., Kimbrel, N.A., & Morissette, S.B. (2015). The structure of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in war veterans. Anxiety Stress Coping 16, 1-10. doi:10.1080/10615806.2015.1081178

Leiva-Bianchi, M. (2011). Relevancia y prevalencia del estrés post-traumático post-terremoto como problema de salud pública en Constitución, Chile. Revista Salud pública 13(4), 551-559.

Lima, B.R., Santacruz, H., Lozano, J., Luna, J., & Pai S. (1988). Primary mental health care for the victims of the disaster in Armero, Colombia. Acta Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de América Latina, 34(1),13-32.

Ling-Xiang, X., & Cody, D. (2011). The Relationship between Interpersonal Traits and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: Analyses from Wenchuan Earthquake Adolescent Survivors in China. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(4), 487–490. doi: 10.1002/jts.20655

López-Ibor, J. (2004). ¿Qué son desastres y catástrofes? Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 32(2), 1-16.

Lopez-Ibor, J., Christodoulou, G., Maj, M., Sartorius, N., & Okasha, A. (2005). Disasters and Mental Health. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England: Wiley.

McFarlane, A., & Norris, F. (2006). Definitions and concepts in disaster research. In F. Norris, S. Galea, M. Friedman, & P. Watson (Eds.), Methods for disaster mental health research (pp. 3–19). New York: Guilford Press.

Matsuoka, Y., Nishi, D., Nakaya, N., Sone, T., Noguchi, H., Hamazak, K., ...Koido, Y. (2012). Concern over radiation exposure and psychological distress among rescue workers following the Great East Japan Earthquake. Public Health 12(249), 1-5. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-249

Mil militares resguardan Atacama: Hay 1.727 albergados y 800 damnificados. (25 de marzo de 2015). Diarioatacama. Recuperado de http://www.soychile.cl/Copiapo/Sociedad/2015/03/25/312324/Rio-se-desborda-y-deja-inundado-a-Copiapo.aspx

Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (2015). MINVU presenta estrategia para reconstrucción de la región de Atacama. Recuperado de http://www.minvu.cl/opensite_det_20150422130517.aspx

Momma, H., Niu, K., Kobayashi, Y., Huang, C., Otomo, A., Chujo, M.,…Nagatomi, R. (2014). Leg Extension Power Is a Pre-Disaster Modifiable Risk Factor for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLOS ONE, 9(4), 1-10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096131

Morina, N., Ehring, T., & Priebe, S. (2014). Diagnostic Utility of the Impact of Event Scale–Revised in Two Samples of Survivors of War. PLOS ONE, 8(12), 1-8.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083916

Moscoso, V. (2013). Caracterización de la escala de gravedad de síntomas del trastorno de estrés post-traumático en personas afectadas por terrorismo de Estado en Chile: un acercamiento a la evaluación del daño. PRAXIS Revista de Psicología, 15(24), 89-114.

Mouthaan, J., Sijbrandij, M., Reitsma, J. B., Gersons, B. P. & Olff, M. (2014). Comparing Screening Instruments to Predict Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. PLOS ONE, 9(5), 1-8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097183

Norris, F.H. & Elrod, C.L. (2006). Psychological consequences of disaster: a review of past literature. F.H., Norris, S. Galea, M.J., Friedman, P.J., Watson (eds). Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research. New York: The Guilford Press.

Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública. ONEMI (2015). Monitoreo por Evento Hidrometeorológico. Recuperado de http://www.onemi.cl/alerta/monitoreo-por-evento-hidrometeorologico/

Ochoa Zaldivar, M., Castellanos Martínez, R., Ochoa Padierna, Z., & Oliveros Monzón, J. L. (2015). Variabilidad y cambio climáticos: su repercusión en la salud. MEDISAN, 19(7), 873-885. Recuperado de http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1029-30192015000700008&lng=es&tlng=es.

Osorio Yepes, C. D., & Díaz Facio Lince, V. E. (2012). Modelos de intervención psicosocial en situaciones de desastre por fenómeno natural. Revista de Psicología Universidad de Antioquia,4(2), 65-84. Recuperado de http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2145-48922012000200005&lng=pt&tlng=es.

Peña-Sarrionandia, A., Mikolajczak, M., & Gross, J. (2015). Integrating emotion regulation and emotional intelligence traditions: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(160), 1-27. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00160

Pérez Benítez, C. I., Vicente, B., Zlotnick, C., Kohn, R., Johnson, J., Valdivia, S., & Rioseco, P. (2009). Estudio epidemiológico de sucesos traumáticos, trastorno de estrés post-traumático y otros trastornos psiquiátricos en una muestra representativa de Chile. Salud Mental, 32(2), 145–153.

Pinchen, Y., Cheng-Fang, Y., Tze-Chun, T., Cheng-Sheng, C., Rei-Cheng, Y., Ming-Shyan, H.,…Hsin-Su, Y. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents after Typhoon Morakot-associated mudslides. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 362–368. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.10.010

Pineda Marín, C., & López-López, W. (2010). Atención Psicológica Postdesastres: Más que un “Guarde la Calma”. Una Revisión de los Modelos de las Estrategias de Intervención. Terapia psicológica, 28(2), 155-160. doi:10.4067/S0718-48082010000200003

Pollice, R.; Bianchini, V., Roncone, R. & Casacchia, M. (2012). Distress psicológico e disturbo post-traumático da stress (DPTS) in una popolazione di giovani sopravvissuti al terremoto dell’Aquila. Rivista di psichiatria, 47(1), 59-64.

Rojas Vilches, O., & Martínez Reyes, C. (2011). Riesgos naturales: evolución y modelos conceptuales. Revista Universitaria de Geografía, 20(1), 83-116. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1852-42652011000100005&lng=es&tlng=es.

Roncone, R., Giusti, L., Mazza, M., Bianchini, V., Ussorio, D., Pollice, R., & Casacchia, M. (2013). Persistent fear of aftershocks, impairment of working memory, and acute stress disorder predict post-traumatic stress disorder: 6-month follow-up of help seekers following the L’Aquila earthquake. SpringerPlus, 2(636), 1-11. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-636.

Rubonis, A., & Bickman, L. (1991). Psychological impairment in the wake of disaster: The disaster–psychopathology relationship. Psychological Bulletin, 109(3), 384-399.

Salcedo, V. (2014). La salud mental ante los desastres naturales. Salud Mental 37(5), 363-364.

Samper Lucerna, E. (2015). Factores de riesgo psicológico en el personal militar que trabaja en emergencias y catástrofes. (Tesis doctoral). Universidad Complutense de Madrid. España.

Soto, F.L. (2013). Impacto de los desastres en la salud mental del personal sanitario de ayuda de emergencia. Revisión bibliográfica. (Tesis de Maestría). Universidad de Oviedo. España.

Takeda, T., Tadakawa, M., Koga, S., Nagase, S., & Yaegashi, N. (2013). Relationship between Dysmenorrhea and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Japanese High School Students 9 Months after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 355-357. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.06.020.

Ugarte, A.M., & Salgado, M. (2014). Sujetos en emergencia: Acciones colectivas de resistencia y enfrentamiento del riesgo ante desastres; el caso de Chaitén, Chile. Revista INVI 80(29), 143-168.

Villalba, C. A. (20 de setiembre de 2012). Plataforma Regional para la Reducción del Riesgo de Desastres en las Américas. Recuperado de http://eird.org/pr14/nota-igninte-stage-todo-desastre-es-socionatural. html

Warsini, S., Buettner, P., Milles, J., West, C. & Usher, K. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the Indonesian version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22, 251–259. doi:10.1111/jpm.12194

Weiss, D.S., & Marmar, C.R. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. En Wilson JP & Keane TM (eds.), Assesing psychological trauma and PTSD: A Handbook for practioners. New York: Guilford Press.

Wu, K.K., & Chan, S.K. (2004). Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Hong Kong J Psychiatry, 14(4), 2-8.

Zhang, Y., Feng, B., Xie, J., Xu, F., & Chen, J. (2011). Clinical Study on Treatment of the Earthquake-caused Post-traumatic Stress Disorder by Cognitive-behavior Therapy and Acupoint Stimulation. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 31(1): 60-63.

Zhiyong, Q., Donghua, T., Qin, Z., Xiaohua, W., Huan, H., Xiulan, Z., . . . Fan, X. (2012). The Impact of the catastrophic earthquake in Chine’s Sichuan province on the mental health of pregnant women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 117–123. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.021

Para citar este artículo:

Lería Dulčić, F., & Salgado Roa, J. (2016). Estrés post-traumático y estrés subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios tras aluvión de barro. Ciencias Psicológicas, 10(2), 129 - 141.

POST- TRAUMATIC STRESS AND SUBJECTIVE STRESS IN COLLEGE STUDENTS AFTER MUDSLIDE

ESTRÉS POST-TRAUMÁTICO Y ESTRÉS SUBJETIVO EN ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS TRAS ALUVIÓN DE BARRO

Francisco Lería Dulčić

Jorge Salgado Roa

Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Atacama. Chile

Abstract: The study is preliminary in nature and aims to describe the levels of symptoms of post-traumatic stress and subjective stress in a sample of 149 college students from Copiapó, Chile. A cross comparative’s associate strategy with natural groups was used. A brief sociodemographic survey and two instruments were applied: Severity Scale Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Impact Event Scale Revised (EIE-R). It was observed that from the total sample the 2% have symptoms of post-traumatic stress; 85% have symptoms of medium intensity impact the event and 13.4% severe symptoms of subjective stress. Significate differences were found in the scores of the scales depending on the varying degree of emotional impact, PTSD, F(4,144) = 17.81, p < .001 and IES-R, F(4,144) = 17.96; p < .001, and grade of material loss, PTSD, F(5,143) = 3.20, p < .01 and IES-R, F (5,143) = 3,26; p < .01. No differences in scores by gender were found. The results suggest low prevalence of PTSD.

Key Words: natural disaster; environmental traumatic event; post-traumatic stress; emotional distress

Resumen: El estudio es de carácter preliminar y tiene como objetivo describir los niveles de sintomatología de estrés post-traumático y estrés subjetivo en una muestra de 149 estudiantes universitarios de Copiapó, Chile Se utilizó una estrategia asociativa de tipo comparativa transversal y un diseño de grupos naturales. Se aplicó una encuesta sociodemográfica breve y los instrumentos: Escala de Gravedad de Síntomas del Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (TEPT) y Escala de Impacto al Evento Revisada (EIE-R). Se observó que del total de la muestra el 2% presenta síntomas de estrés postraumático; el 85% presenta síntomas de mediana intensidad de impacto al evento y el 13,4% síntomas severos de estrés subjetivo. Se presentaron diferencias significativas en los puntajes de las escalas en función de la variable grado de impacto emocional, TEPT, F(4,144) = 17.81, p < .001 y EIE-R, F(4,144) = 17.96; p < .001, y grado de pérdida material, TEPT, F(5,143) = 3.20, p < .01 y EIE-R, F(5,143) =3.26; p < .01. No se presentan diferencias en las puntuaciones en función del sexo. Los resultados sugieren la existencia de baja prevalencia de estrés postraumático.

Palabras Clave: desastres naturales; eventos ambientales traumáticos; estrés post-traumático; malestar emocional

Received: 01/2016 Reviewed: 04/2016 Accepted: 07/2016

Correspondencia: Francisco Lería D., Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Atacama. Chile.

Correo Electrónico: francisco.leria@uda.cl

Introduction

The impact of climate change on population and infrastructure and its effects are more frequently possible to be seen, and this impact, due its unpredictability, becomes a challenge for authorities. This change is caused by different elements and include various climatic parameters (temperature, frost, pressure, wind, rain, etc.). In the latter years, the term anthropogenic climate change and/or anthropic danger has been coined to point out the influence of the human variable in its origin (Oreskes, 2004; Rojas Vilches, & Martínez Reyes, 2011) and the name of socio-natural disaster given to relieve the impact these changes have on people (Villalba, 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO), in its 2008 declaration, addressed the issue of global climate change, highlighting the consideration of direct health threat (Chang, 2008, as quoted in Ochoa Zaldivar et al., 2015). Since then, the importance of disaster research has been recognized and a considerable amount of studies concerning its effects on mental health has proliferated (de la Barra, & Silva, 2010; Salcedo, 2014), together with some of its related concepts such as vulnerability, resilience and risk management (Aledi, & Sulaiman, 2014).

Stress reactions are some of the responses to disastrous events have been the subject of extensive study and it is known they have a high impact on mental health. Their effects tend to persist over time and become, most of the times, chronic, technically called post-traumatic stress. The specialized literature shows how these responses, which are a variable phenomenon and dependent on the type of traumatic event, increase significantly in cases of disaster victims, disasters and natural and/or socially induced emergencies (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011). It has been stated that the nature of these events and their sudden and intense character is associated with a number of symptomatologic stress responses and finally to mental disorders, in which the ability of daily functioning of the person is highly compromised. The psychological impact of a catastrophic event and its consequent post-traumatic stress response, tends to last over time in both direct and indirect victims (Samper, 2015); with an estimated prevalence in the world population highly variable between 4% to 70%; specifically in Chile from 4.4% to 36% (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011;. Pérez et al., 2009).

The post-traumatic stress disorder is a type of anxiety disorder characterized by the appearance of symptoms after being exposed to a stressful event and selectively displayed when the person is exposed to stimuli that resemble an aspect of the traumatic event. This autonomic arousal produces a series of difficulties such as sleep problems, irritability, concentration difficulty, hypervigilance, social and/or labor deterioration, among others (American Psychiatric Association, 2002).

Psychosocial research in disasters has been initially focused on the impact on the physical and mental health of the victims, later on the behavior of groups of people who have experienced disastrous events, in which its members find themselves overwhelmed with their habitual mechanism of dealing with or coping with (Lopez-Ibor, Christodoulou, Maj, Sartorius, & Okasha, 2005). Classic meta-analytic studies such as Rubonis and Bickman (1991), noticed that the anxious-depressive symptoms (eg. excessive consumption of alcohol) were more frequent and had a higher prevalence. Contemporary studies have emphasized other post-traumatic reactions to disaster, such as lack of control and loss of confidence (Pineda Marín, & López-López, 2010). The character of the post-traumatic response varies and has elements in common with respect to the type of disaster. For example, exposure to earthquakes is associated with high levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as in the earthquake of May 12, 2008 in China, Sichuan Province, where the prevalence of PTSD after 18 months was 12.2% and 40.8% for depressive symptoms (Zhiyong et al., 2012). In the Haiti earthquake of January 12, 2010, a prevalence of 36.75% was observed for PTSD; 25.98% for depressive symptoms in adult population victims (Cénat, & Derivois, 2014); and 22.25% of PTSD in minor victims (Cénat, & Derivois, 2015) after 30 months; also highlighting how professionals with previous experience in this type of situations, e.g.: volunteers and/or military personnel, get higher scores on the measurement of PTSD symptomatology (Guimaro, Santesso Caiuby, Pavão dos Santos, Lacerda, & Baxter Andreoli, 2013); a finding already present in previous scientific literature (Soto, 2013). In a sample of youngsters after 9 months the earthquake and explosion of the nuclear plant in Fukushima, Japan, on March 11, 2011, high levels of PTSD and comorbidity were observed with menstrual pain and dysmenorrhea (Matsuoka et al., 2012; Takeda, Tadakawa, Koga, Nagase, & Yaegashi, 2013). On the European continent, after the earthquake in the city of L’Aquila in Abruzzo Italy on April 6, 2009; PTSD symptoms and neuropsychological difficulties associated with retrograde memory were detected after 6 months of the event, mainly caused by the persistent fear for aftershocks (Roncone et al., 2013).

In the case of exposure to Tsunamis, such as the one in the Indian Ocean in 2004, a prevalence of PTSD between 20 and 30% was found after 6 months, highlighting the peritraumatic fear, neuroticism and low levels of social support as inducer factors of post-traumatic stress response (Hussain, Weisæth, & Heir, 2013).Snowstorm catastrophes have also been investigated, such as the one occurred in China, Hunan Province, between January 25 and February 6, 2008, with a prevalence in young victims of 14.5% for PTSD, concluding that most prominent factors for the development of the disorder risks are: home-school distance, low stress coping strategies, neuroticism and the presence of emotional support from their teacher (Daxing, Huifang, Shujing, & Ying, 2011).

In the case of landslides and avalanches of mud and water disasters, such as the one caused by the volcanic eruption on August 12 and 13, 1985 in Armero, Colombia, depression, generalized anxiety and PTSD were the 3 most frequent diagnoses 8 months after the disaster (Lima, Santacruz, Lozano, Luna, & Pai, 1988). Autonomic hyperarousal has been recognized as the most prevalent symptom in this kind of catastrophe (Craparo, Faraci, Rotondo, & Gori, 2013). In another study in Taiwan after Typhoon and flood Morakot occurred on August 8, 2009; 25.8% of PTSD, particularly intrusive thoughts, physiological and psychological hyperarousal, and avoidance was found (Cheng-Sheng et al., 2011). One important concern is the high prevalence of PTSD (25.8%) found in this type of disaster in young victims after 3 months of a flood, caused by anxiety symptoms and intrusive type of irruptive in cognitive development (Pinchen et al., 2011).

Research has also been conducted on survivors of tornadoes, as in the case of Katrina occurred on August 20, 2005 in the United States, finding a positive relationship between direct exposure to catastrophe, symptoms of PTSD and the occurrence of asthmatic episodes (Arcaya, Lowe, Rhodes, Waters, & Subramanian, 2014).

However, post-war traumatic effects have been more than any other studied event. There are 3961 studies only on the database PunMed to January 2016. Current studies emphasize six common symptomatological factors in this type of traumatic experience: intrusive thoughts, avoidance, negative affect, anhedonia, dysphoria and anxious arousal (Konecky, Meyer, Kimbrel, & Morissette, 2015). There are other interesting areas of research in this regard, for example, the effects on civilian victims by war disaster and their vision and sense of life during the process of social reconstruction (Čorkalo, Ajdukovic, & Low, 2014).

Despite the uniqueness of these results in relation to the high prevalence of PTSD in victims of disasters, it has been shown to be highly dependent on the nature and characteristics of the traumatic event, as well as the victims who experience it. For example, the particular post-traumatic effects after a complex catastrophe like the earthquake and tsunami in Chile on February 27, 2010, showed a prevalence of PTSD much higher than expected, between 20% and 36% (Leiva-Bianchi, 2011). Finally, among the factors of risk for the appearance of PTSD after exposure to disasters are: the low educational level, sex of the victim, the premorbid presence of obsessive-compulsive traits, the presence of emotions of grief and despair, having children under 6 years old, social displacement because of material losses, lack of social support after the event, the absence of precautionary measures against the possibility of a disastrous event, and premorbid background for the development of PTSD (Chen et al., 2014; Pollice, Bianchini, Roncone, & Casacchia, 2012). Other modulating variables of post-traumatic appearance and effect are: sex, gender, education level, injury and/or death in the time of occurrence of the disastrous event (Grimm, Hulse, Preiss, & Schmidt, 2012). On the other side, there are protective common factors such as: social independence, interpersonal initiative, social responsibility and social openness (Ling-Xiang, & Cody, 2011); perceived emotional stability (Hussain, Weisæth, & Heir, 2013); and fitness (Momma et al., 2014).

According to McFarlane and Norris (2006), disasters can be classified as natural (hurricanes, earthquakes, floods), as opposed to “human” disasters which in turn can range from unintentional accidents to deliberate actions (eg. terrorism). The specialized literature has emphasized, however, that the exclusive designation natural disaster has the risk of masking the true impact of social factors on the action of nature. These factors are the first modulators of stressful experience lived by victims. According to Cova and Rincón (2010), quoting several authors, these distinctions have been questioned, pointing out that although in some disasters the triggering factor is a natural event, greatly uncontrollable, its implications and effects are derived from human action. As an example of this, the meta-analytical studies have shown that the impact on mental health in members of the victim communities of a catastrophe from less developed countries is variable (Norris, & Elrod, 2006).

The concept socio-natural disaster is currently used to integrate the variables involved in the origin of disastrous events, along with changing aspects of the traumatic experience of the victim. In addition, it seeks to clarify “the responsibilities of the different actors and to ensure that governments, multilateral agencies and non-governmental organizations contribute to reduce risks, to avoid events, reduce impacts” (Villalba, 2012). Moreover, the study of models of intervention in disasters and emergencies reveals that the psychosocial impact of a disastrous event is linked to a large extent to the poor preparation that communities and governments have (Osorio Yepes, & Díaz Facio Lince, 2012). Hence, the definition of a sociocultural factor is essential in order to evaluate the actual effects of a disaster which can be measured by the impact they have on the society that experiences it. According to Arnold-Cathalifaud (2010), in the case of Chile and the disaster occurred of February 27, 2010, with its “earthquake and all its aftershocks together, is less than the social earthquake in the country” (p. 41), the author adds: “No one can be guilty of an earthquake or a tsunami, as they are natural phenomena, however, responsibility for a bad preparedness, by poor construction, poor design of hospitals or airports can be imputed” (p. 41). Other studies have emphasized that the impact of a catastrophe is, at first, a natural event, and then it becomes a socio-natural occurrence which shows how the State makes a series of interventions that are perceived by the population as aggravating the same natural disaster (Ugarte, & Salgado, 2014). Research on this matter confirms these claims. An example of how the human factor can be aggravating against fortuitous and/or unexpected events, is the case of the disaster which occurred in Estonia on September 28, 1994, when a passenger boat sank leaving 852 dead persons and only 137 rescued after several hours floating in adverse weather conditions. In this study, survivors were evaluated three months, one year, three years, and fourteen years after the catastrophe, and the prevalence of PTSD was 27% (Arnberg, Eriksson, Hultman, & Lundin, 2011). In the case of Chile, studies have described the prevalence and severity of PTSD symptoms in people affected by the military dictatorship that took place between 1973 and 1990, revealing a greater presence of anxiety symptoms in women and people who did not politically participate at the time of political repression, recording more symptoms of avoidant type (Moscoso, 2013).

The impact of a disaster depends not only on direct exposure to the stressful event (earthquake, landslide, fire, etc.), but also on loss, damage and feelings of threat felt by people and their immediate milieu, as well as medium and long range consequences (Felix, & Rincón, 2010). These effects tend to affect particularly at each individual and/or victims group, giving way to a special and selective effect and not to a global reaction of undifferentiated stress. For example, the aforementioned earthquake and tsunami in southern Chile (February 27) caused high stress levels in a group of workers without a decrease in job satisfaction (Jimenez, & Cubillos, 2010). Finally, there are records regarding the impact of individual treatment to disaster victims (Figueroa, Marín, & González, 2010; Zhang Feng, Xie, Xu, & Chen, 2011), as well as the effectiveness of psychosocial oriented programs aiming at the improvement of stress coping strategies (Bianchinia et al., 2013). Osorio and Díaz (2012) mention 30 models and documented experiences of psychosocial intervention in disasters in Spain and Latin America. These investigations have shown that the latency of the intervention (e. g. rescue or essential supplies), the presence of abundant material support, post-event psychosocial support spaces and special attention to high-risk groups, all play a central role in the rehabilitation of victims of disasters and emergencies (Chen et al., 2014).

On March 25, 2015 the largest rainfall disaster in 80 years in the Chilean regions of Antofagasta, Atacama and Coquimbo occurred. The event brought heavy rainfall in a short period of time followed by the overflowing of Copiapó and El Salado rivers, and landslides coming mainly from mine tailings located around the city (27 ° 21 ‘59 “S 70 ° 19 ‘59 “W). As a result, there were several interrupted or isolated routes, destroyed homes, power and fiber optics outages, among other impacts. The Government decreed a catastrophe zone and then a state of emergency, and a thousand soldiers were sent to safeguard public order and provide aid to the affected areas (“Thousand Soldiers Guard Atacama”, 2015).

The population was exposed to a series of stressful events for at least 10 days after the disaster, mainly by power outages and water shortage, full stop traffic in many areas of the city and the non-functioning of basic services. In addition, a significant rise in prices of basic goods, and attempted looting (Gutiérrez, 2015) were observed. Official data estimates more than 28.000 victims and 31 dead people, 16 missing (according to denunciation for presumed misfortune); and 16.588 damaged (Interior Ministry’s National Emergency Office, 2015). Moreover, the existence of 43% of homes with repairable damage; 23% of slight damage; 13% of moderate damage; 7% of severe damage; and 6% of non-repairable damage requiring replacement or complete housing rebuilding was detected (Ministry of Housing and Urban Development , 2015). The city found itself highly sectorized. For example, the alleys of the city, were flooded almost completely, unlike the high sectors, which suffered no damage. In addition, after some time, the city was affected by air pollution, damage to public and pedestrian routes, trash and piles of mud piled up in different parts of the city, among other effects and residues of the alluvial situation, which posed the presence of permanent stress factors that prolong the impact of the disaster in time.

Considering the above background, the questions that guide the present study are as follows; 1) What are the levels of symptoms of post-traumatic stress and subjective stress after the flood?; 2) What socio-demographic factors determine the variability of PTSD and IES-R scales?; 3) Does the degree of emotional impact and material loss determine the variability of results in PTSD and IES-R scales?

The objective was to identify post-traumatic stress symptom levels and subjective stress in university students after the mudslides an determine factors of their variability.

Materials and Methodology

Research Design

This study is an empirical research. A partnership strategy of cross-comparative type and design of natural groups were used. Variables are not manipulated and the relationships among them are analyzed by investigating the differences between two or more groups of individuals from the contrasts generated by nature and society (Ato, López, & Benavente, 2013).

Participants

An intentional non-probability or convenience sampling was used. 149 college students participated in the city of Copiapó, who were selected because they were pursuing careers that are dictated in a university campus severely affected by the flood, and that had access and normal operation problems during several months after the disaster. As for the characteristics of the sample, 19.5% were male, and 80.5% female gender; ages range was between 17 and 25 years (M = 19.71 and SD = 3.22), of which 96.6% were single. In addition, 38.3% reported being affected by the mud at different levels of severity and 16.7% reported emotional impact with different levels of intensity (see table 1).

Instrumentos

The following was used: The Scale Severity of Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD; Echeburúa, Corral, Love, Zubizarreta, & Sarasua, 1997a), which corresponds to a scale of assessment of PTSD symptoms according to criteria found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). It comes in Likert-type format (0 = Nothing to 3 = 5 or more times per week), which includes 17 questions grouped in three dimensions (intrusive re-experience, avoidance, and activation). It also has a complementary somatic manifestations subscale. It has been validated in Spain with victims of sexual assault and domestic violence, presenting high levels of reliability through its temporal stability and internal consistency (alpha of 0.89 and 0.92 respectively), which proves to be an instrument that exceeds the minimum requirements for being used in research settings, clinical and/or legal forensics included (Blasco-Ros, Sánchez-Lorente, & Martínez, 2010; Echeburúa, Corral, Amor, Sarasua, & Zubizarreta, 1997b; Echeburúa, Corral, & Amor, 2003). It was applied in Chile by Moscoso (2013) to people affected by State terrorism obtaining satisfactory Alpha coefficients in all dimensions (between 0.86 and 0.94), and an Alpha of 0.96 for the overall result, which indicates high internal consistency and a satisfactory level of reliability. The questionnaire provided an adequate discriminant validity of the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress unlike other anxiety disorders.

The Impact Scale Event Revised (IES - Impact of Event Scale Weiss & Marmar, 1997); validated in Spain by Baguena et al. (2001). This is an instrument that has 22 items and 3 subscales (Intrusion, Avoidance and Hyperarousal) of Likert type to evaluate the intensity of symptoms (from 0 = None to 4 = Extremely). It allows to measure, form the global score, the severity of emotional distress or subjective stress (Costa Requena, & Gil Moncayo, 2012). This instrument has been used in various research regarding the impact of disasters and emergencies (Arcaya et al., 2014; Brunet, St-Hilaire, Jehel, & King, 2003; Caamaño, González, & Sepúlveda, 2011; Creamer, Bell, & Failla, 2003;, Giorgi et al., 2015; Morina, Ehring, & Priebe, 2014; Warsini, Buettner, Mills, West, & Usher, 2015), including mudslides (Cheng-Sheng et al., 2011; Craparo et al., 2013); and its psychometric properties have been evaluated in China showing appropriate values (Wu, & Chan, 2004). It also presents 72% sensitivity for the detection of PTSD in relation to other similar psychometric instruments (Mouthaan, Sijbrandij, Reitsma, Gersons, & Olff, 2014). The IES-R was adapted and validated for Chilean population by Caamaño et al. (2011), concluding that it is a reliable measure of self-reporting and of adequate validity.

Sociodemographic Survey. This survey was devised by the authors to collect information such as age, sex, college career, marital status, place of residence, place where the person was during the day of the flood, degree of material loss (consisting of 6 levels, 1 = Mud did not affect my sector; 6 = the mud completely destroyed my house), and degree of emotional impact reported (5 levels, 0 = None; 4 = loss / death of a relative), all of this being of nominal and ordinal character, except the age of the individual.

Procedure

The instruments were applied three months after the mudslide, previously approved by a scientific qualified committee of the institution of the authors which approved the ethical aspects of the study. The Chairs of the different Departments of the institution granted formal permission to access the classrooms of participating students. The research collaborators presented the objectives of the study and stated the anonymous and confidential nature of the obtained data. Once this was communicated to the participants, a package containing the two scales, the socio-demographic questionnaire, and an informed consent to be returned in a sealed envelope to ensure confidentiality of the data, was handed in. The differences were estimated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) of a factor depending on sociodemographic variables and categories of degree of material loss and emotional impact. For the gender category, the Student t-test was used for independent samples. Homogeneity of variance was determined by the Levene’s test, in the absence of it, the Welch test was applied (Armitaje, Berry, & Matthews, 1994). The post-hoc comparisons were made using the Tukey’s test. Cohen’s d and partial Eta squared (ηp2) were used to measure the effect size (Cohen, 1988). Linear regressions were performed using the stepwise method.

Results

The main results of the study, which are of preliminary nature, are presented below.