Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.10 no.1 Montevideo mayo 2016

EVIDENCE OF VALIDITY OF THE LSB-50: CROSS-VALIDATION, FACTORIAL INVARIANCE AND EXTERNAL CRITERION ANALYSIS

EVIDENCIAS DE VALIDEZ DEL LSB-50: VALIDACIÓN CRUZADA, INVARIANZA FACTORIAL Y VALIDEZ DE CRITERIO EXTERNO

Mercedes Fernández Liporace** ***

*Universidad de Palermo. Argentina

**Universidad de Buenos Aires. Argentina

***CONICET. Argentina

Resumen: Este trabajo tuvo como objetivo obtener evidencias de validez del LSB-50 (de Rivera & Abuín, 2012), un instrumento psicométrico de screening (despistaje) para medir psicopatología, en una muestra de adolescentes argentinos. Los participantes fueron 1002 individuos (49.7% hombres; 50.3% mujeres) de edades entre 12 y 18 años (M = 14.98; DE = 1.99). Se llevaron a cabo estudios de validación cruzada e invarianza factorial para probar la adecuación de un modelo de siete factores correspondientes a las siete escalas clínicas del LSB-50 (Hipersensibilidad, Obsesiones-Compulsiones, Ansiedad, Hostilidad, Somatización, Depresión, y Alteraciones del sueño) en muestras divididas de acuerdo al sexo y edad de los evaluados. La estructura de siete factores demostró tener un buen ajuste en las cuatro submuestras. Luego, el ajuste del modelo se estudió simultáneamente en las muestras mencionadas a través de modelos jerárquicos en los que se impusieron distintas restricciones de igualdad. Los resultados indicaron la invarianza de las siete dimensiones del LSB-50. El cálculo de alfas ordinales indicó que todas las escalas tenían un buen nivel de consistencia interna. Finalmente, las correlaciones con una medida externa de diagnóstico de psicopatología (PAI-A) indicaron, tal como era esperado, una convergencia moderada. Se concluye que los análisis realizados proveen de contundente evidencias de validez del LSB-50.

Palabras Clave: LSB-50; cribado en psicopatología; validez de constructo; invarianza factorial; validación cruzada

Abstract: The aim of this paper was to obtain evidence of the validity of the LSB-50 (de Rivera & Abuín, 2012), a screening measure of psychopathology, in Argentinean adolescents. The sample consisted of 1002 individuals (49.7% male; 50.3% female) between 12 and 18 years-old (M = 14.98; SD = 1.99). A cross-validation study and factorial invariance studies were performed in samples divided by sex and age to test if a seven-factor structure that corresponds to seven clinical scales (Hypersensitivity, Obsessive-Compulsive, Anxiety, Hostility, Somatization, Depression, and Sleep disturbance) was adequate for the LSB-50. The seven-factor structure proved to be suitable for all the subsamples. Next, the fit of the seven-factor structure was studied simultaneously? in the aforementioned subsamples through hierarchical models that imposed different constrains of equivalency?. Results indicated the invariance of the seven clinical dimensions of the LSB-50. Ordinal alphas showed good internal consistency for all the scales. Finally, the correlations with a diagnostic measure of psychopathology (PAI-A) indicated moderate convergence. It is concluded that the analyses performed provide robust evidence of construct validity for the LSB-50.

Key Words: LSB-50; psychopathological screening; construct validity; factorial invariance; cross-validation

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) under Grant PIP 11220110100504/2012-2014, Res. 2043/14.

Correspondencia: Guadalupe de la Iglesia, Universidad de Palermo.

Correo Electrónico: gdelaiglesia@gmail.com

Recibido: 01/2016

Revisado: 03/2016

Aceptado: 04/2016

Psychopathology in adolescence

Although the risk of psychopathology exists during the complete cycle of life, adolescence is a stage when the chances of developing psychological symptoms are intensified (Jessor, 1991). One of the reasons is the predisposition of young people to engage in risk-taking behaviors. Though some risk behaviors are considered desirable, expected, or even beneficial (Ellis et al., 2012), their association with psychological symptoms should not be overlooked (e.g., Vrouva, Fonagy, Fearon, & Roussow, 2010). Jessor’s (1987) Problem Behavior Theory (PBT) posits that engagement in risk-taking behaviors may be related to adolescents’ need to oppose society norms. It is believed, that this conduct is temporary and will decline in adulthood (Briggs, 2009; Graham, 2004). However, in the meantime, they favor adolescents’ vulnerability to psychopathology.

The presence of psychopathology does not only entail a personal discomfort but it is also related to other unwanted consequences. Research has shown that psychological symptoms in adolescence are related, for example, to defective social functioning, low academic achievements, family stress (e.g., Angold, Costello, & Worthman, 1998; Kofler et al., 2011; Quiroga, Janosz, Bisset, & Morin, 2013) or even psychological symptoms in adulthood (e.g., Helgeland, Kjelsberg, & Torgersen, 2005; Stepp, Olino, Klein, Seely, & Lewinsohn, 2013). In consequence, identifying those adolescents at risk of developing some kind of psychopathology constitutes an important goal.

It is estimated that nearly 20% of the Argentinean population suffers from some type of psychological symptom (Ministerio de Salud, 2010). However, these statistics are just estimations based on data from other Latin-American countries as there is a lack of epidemiological information from Argentina. One of the reasons for the nonexistence of local statistics relies on the absence of valid and reliable screening tools for assessing psychopathology in Argentina.

Screening psychometric tests constitute appropriate tools when the objective is to rapidly assess certain psychological characteristics in a population (Hernández-Aguado, Gil de Miguel, Delgado Rodriguez, Bolúmar Montrull, Benavides, Porta Serra, Álvarez-Dardet Díaz, Vioque López, & Lumbrera Lacarra, 2011; Lewis, Sheringham, Kalim, & Crayford, 2008). For instance, its use becomes fundamental for a pivotal concern of public health: the study of psychopathology prevalence in the community (Kohn et al., 2005). Therefore, the development of this type of instruments constitutes a prerequisite for pursuing public health issues such as: establishing the prevalence of psychopathology, studying possible factors associated with it, and detecting subjects at risk of developing a mental disorder in order to implement early interventions.

Common features of screening measures of psychopathology

Screening measures of psychopathology are usually self-report Likert scales that ask respondents about a diverse range of psychological symptoms. There is a debate regarding the accuracy of the use of self-reports. However, it has been established that self-reports not only result adequate for screening purposes but also allow individuals to freely and sincerely communicate their symptoms (Corcoran & Fischer, 2000; de Rivera & Abuín, 2012).

The most frequently used screening measure of psychopathology is the revised version of the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1983). As its length was unsuitable for screening purposes, a briefer version was developed: the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis 1975; Derogatis, & Spencer, 1982). Then, an even shorter version of the scale was proposed: the BSI-18 (Derogatis, 2001). Although, the SCL-90-R is commonly applied, the three versions of the scale are frequently employed both in research and applied fields (e.g. Aroian, Patsdaughter, Levin, & Gianan, 1995; Torres, Miller, & Moore, 2013; Zhang & Zhang, 2013).

The SCL-90-R has been heavily criticized. Some of the denoted flaws are: inadequate wording, type of symptoms assessed, length, and most importantly, lack of factorial evidence, among others (e.g. Bados, Balaguer, & Coronas, 2005; de Rivera & Abuín, 2012; Sandín, Valiente, Chorot, Santed, & Lostao, 2008). Holi (2003), for example, pointed out that the SCL-90-R has some evidence of discriminant validity as it usually differentiates normal or control samples from patients. However, researchers have had difficulties replicateing the original nine-dimension structure in factor analyses.

Due to the SCL-90 shortfalls, newer versions of the instrument have been developed. Davison et al. (1997), for example, designed another shorter version named Symptom Assessment-45 Questionnaire (SA-45). Despite the intention of introducing improvements, some of the flaws of the original instrument remained in the newer version as well as in its adaptations (Alvarado, Sandín, Valdez-Medina, González-Arratia & Rivera, 2012; Sandín et al., 2008).

Considering the aforementioned scenario, de Rivera and Abuín (2012) recently developed the Listado de Síntomas Breve (LSB-50) –Short Checklist of Symptoms–. This psychometric test tends to overcome some of the SCL-90 alleged flaws. The improvements made were, for example, the exclusion of both Psychoticism and Paranoid Ideation scales, as respondents find its symptoms unclear and difficult to understand, and because those symptoms could be easily detected in clinical interviews. Moreover, Eaton, Neufeld, Chen, and Cai (2000) indicated that psychotic disorders should not be addressed by self-report measures. Additionally, psychometric studies have shown that both scales do not emerge as singular factors in factor analyses (Prunas, Sarno, Preti, Madeddu, & Perugini, 2012). Other improvements of the LSB-50 were the language adjustment in order to obtain a more accurate equivalence of terms, and the addition of a new scale to assess sleep disorders.

The resulting 50-item measurement of psychopathology was designed to enable users to calculate different measures. The severity of symptoms may be addressed in four indexes: (a) Global Severity index, (b) Number of Symptoms, (c) Intensity of Symptoms index, and (d) Risk of Psychopathology index. Then, seven main clinical scales can be evaluated: Hypersensitivity, Obsessive-Compulsive, Anxiety, Hostility, Somatization, Depression, and Sleep disturbance. Additionally, two clinical scales: Psychoreactivity, which addresses both Obsessive-Compulsive and Hypersensitivity symptoms; and, Sleep disturbance extended, that combines the assessment of Anxiety and Depression symptoms related to sleep. Distortions in responses may be analysed by the Magnification and Minimization scales.

Since the LSB-50 is a relatively new measure, there is not yet much evidence of its psychometric properties in different populations. Until now, this instrument has been studied in Spanish, Colombian and Argentinean populations (Abuín & de Rivera, 2014; de la Iglesia, Fernández Liporace, & Castro Solano, 2015; Rojas Gualdrón, 2012). The analyses conducted with the scale include: internal consistency by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, and discriminant analysis. Although the test was originally developed to be used in adults, the psychometric study performed in Argentina showed excellent results within adolescents. In detail, the LSB-50 has shown to have adequate internal consistency by Cronbach’s alphas and confirmatory factor analysis of a second order factorial structure resulted in a excellent fit of a model were the seven aforementioned clinical scales loaded in a higher psychopathology dimension.

Factorial analyses

Factorial analyses of psychopathology screening instruments tend to be intricate and inconstant. In the case of the tests mentioned –SCL-90-R, BSI, BSI-18, SA-54–, for example, items showed complex loadings and models presented different amount of factors (Cyr, McKenna-Foley, & Peacock, 1985; Martínez Azumendi, Fernández Gómez, & Beitía Fernández, 2001). Factorial structures range from a one-factor model to two, five, six and even eight dimensions (e. g. Abuín & de Rivera, 2014; Daoud & Abojedi, 2010; De Las Cuevas et al., 1991; Hoffmann & Overall, 1978; Urbán et al., 2014). According to de Rivera and Abuín (2012), one reason for these inconsistencies in factorial structures might be clinical comorbidity of disorders.

A recurrent finding in exploratory factor analyses (EFA) is a unique higher-order dimension usually conceived as a measure of general psychiatric discomfort (Benishek, Hayes, Bieschke, & Stoffelmayr, 1998; Bonynge, 1993; Boulet & Boss, 1991; Cyr et al., 1985; Daoud & Abojedi, 2010; Grande, 2014; Loutsiou-Ladd, Panayiotou, & Kokkinos, 2008; Martínez Azumendi et al., 2001; Piersma, Boes, & Reaume, 1994; Prunas et al., 2012; Torres et al., 2013; Zack, Toneatto, & Streiner, 1998). Particularly, in the case of the SCL-90-R, the constant failure to replicate the postulated structure of nine scales derived in questioning the suitability of such dimensional structure. The lack of factorial evidence makes it almost impossible to justify the use of the proposed nine scores. In fact, Bados et al. (2005) stated that the use of a unique measure of psychological discomfort might be the better option. Thus, although appropriate and informative, a general measure of psychopathology does not meet all the needs of researchers and clinicians.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), also display the same difficulty in replicating the multidimensionality of the psychopathology screening measures. Again, the SCL-90-R has shown inadequate fit indexes for the proposed nine-factor structure (Hardt, Gerbershagen, & Franke, 2000; Ming-zhi, Heng-fen, & Huei-fang, 2004; Rauter, Leonard, & Swett, 1996; Schmitz et al., 2000; Vassend & Skrondal, 1999), or just merely acceptable ones (Urbán et al., 2014). CFA of the BSI showed results just below the required value (Liu, Chen, Cao, & Jiao, 2013) or simply inadequate values (Benishek et al., 1998). In the case of the SA-54, indexes of fit do not meet the expected results either (Alvarado et al., 2012; Sandín et al., 2008). While the LSB-50 showed good fit in a CFA conducted in Colombian population (Rojas Gualdrón, 2012); the dimensions found differed from those proposed by de Rivera and Abuín (2012).

Cross validation and factorial invariance

Cross validation studies also provide important evidence of validity for psychometric tests. That is, the search of evidence that indicates if a factorial structure shows to be valid across different groups divided by a certain characteristic (e.g. sex, age). In the case of the SCL-90-R, Martínez Asumendi et al. (2001) did not obtain any satisfactory results when conducting cross validation of different factorial models. However, Torres et al. (2013) analysed the cross validation of a one-factor and a three factor structure of the BSI-18 across a sample divided by nationality, sex and language with acceptable results.

An even more demanding test of validity is the study of factorial invariance. In this analysis, the equivalence in the fit of the factorial structure and the equivalence in the function are examined simultaneously across different groups. For instance, one particular study found that the variability of nine-factor structure of the SCL-90-R did not remain the same when the sample was divided by sex (Vassend & Skrondal, 1999). In the case of the BSI, when analysing just a one-factor model, the factorial invariance was satisfactory across clinical and general population samples (Daoud & Abojedi, 2010), but it was not adequate between adolescent and adult samples (Piersma et al., 1994). In the same line, Torres et al. (2013) tested the factorial invariance of a one-factor and a three-factor model of the BSI-18 across sex, language and nationality. Results only showed invariance across sex.

Studying the invariance of the explored and the confirmed factorial structures results crucial for guaranteeing the quality of the measure. A positive result would not only suggest that the structure shows a good fit statistically speaking, but also that its results remain constant throughout different groups.

Internal consistency assessment

Most screening measures are formed by items answered in a Likert scale and scholars commonly use Cronbach’s alphas to assess internal consistency. However, Elosúa and Zumbo (2008) posit that this procedure is not completely accurate and, instead, they proposed to use a method that takes into account the ordinal nature of the elements, such as the ordinal alpha. This statistic is based on the correlations obtained by a polychoric matrix, which is a more appropriate calculation for semi-quantitative data. That is, psychopathology screening measures that use Likert scales to gather data should include the assessment of internal consistency by ordinal alphas. In the aforementioned psychometric instruments, the internal consistency was performed by the estimation of Cronbach’s alpha and, predominantly, results show a good internal consistency (e.g. Abuín, & de Rivera, 2014; Caparrós Caparrós et al. 2007; Carrasco Ortíz, Sánchez Moral, Ciccotelli, & del Barrio, 2003; Casullo & Castro Solano, 1999; Ruipérez, Ibáñez, Lorente, Moro, & Ortet, 2001).

External criterion validity: Diagnostic tests or gold standards

Psychometric instruments may be classified into two main groups: diagnostic tests and screening tests. Diagnostic tests are characterized by a thorough, specific and extensive evaluation. Screening measures, on the other hand, aim to detect risk cases by a brief and simple assessment (Hernández Aguado et al., 2011; Lewis, Sheringham, Kalim, & Crayford, 2008). However, when studying the psychometric properties of a screening measure, diagnostic tests are helpful to analyse the appropriateness of the screening instrument. Correlations between these measures should be positive and moderate, indicating that although both instruments assess the same construct in a considerable degree, the measures are not interchangeable. Usually, individuals identified as ‘at risk’ need to continue with a proper diagnostic procedure. The initial selection of cases allows a better use of resources. Therefore, studying if the LSB-50 correlates with an external diagnostic criterion of psychopathology such as the Personality Assessment Inventory for Adolescents (PAI-A; Morey, 2008) would allow to analyse the validity of the LSB-50. Consequently, the objectives of the present study were: (1) to cross validate the LSB-50’s seven-factor structure in four subsamples (males, females, adolescents of 12-15 years old, adolescents of 16-18 years old); (2) to test the LSB-50’s factorial invariance across sex and age; (3) to study the LSB-50’s internal consistency of each scale using ordinal’s alphas; and, (4) to study the associations of the LSB-50’s clinical scales scores with an external criterion of psychopathology (PAI-A).

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1002 Argentinean adolescents between 12 to 18 years old (M = 14.98; SD = 1.99). Sex distribution was proportional (49.7% male; 50.3% female). Regarding family’s characteristics, 64% of the participants were raised by both parents, 29.2% was resided by one of their parents, and a small percentage had their father (2.9%) or their mother (0.7%) passed away. Finally, 65.1% of the sample reported having one or two siblings, 22.3% three or more brothers or sisters, and 11.3% was an only child.

For the cross-validation and invariance testing analysis, the main sample was divided into female and male subsamples. The mean age was 15.00 years (SD = 1.99) for the female subsample (n = 504) and 14.96 (SD = 1.98) for the male subsample (n = 498). Additionally, the main sample was divided into age groups: 12 to 15 years old (n = 577) and 16 to 18 years old (n = 425). As in Argentina, adolescents acquire different civil rights - as the option to vote and to drive vehicles - at the age of 16, this age was used as the rationale to split the sample.

Materials

- Listado de Síntomas Breve - Short Checklist of Symptoms - (LSB-50; de Rivera & Abuín, 2012; de la Iglesia, Fernández Liporace, & Castro Solano, 2015). This is a 50-item scale that assesses different psychological symptoms in seven main clinical scales: (a) Hypersensitivity (seven items), that refers to intra and interpersonal sensitivity (e.g. “I think other people look at me or talk about me”); (b) Obsessive-Compulsive (seven items), which attempts to cover the presence of doubts, rituals, and compulsions (e.g. “I have to do things very slowly in order to be sure that I am doing them properly”); (c) Anxiety (nine items), that enquires about symptoms of panic, general anxiety disorder and phobic disorders (e.g. “I feel fearful in the street or in open spaces”); (d) Hostility (six items), which asks about behaviours of rage, anger and resentment (e.g. “I want to break or destroy something”); (e) Somatization (eight items), that assesses somatic symptoms that have basis on psychological or medical problems (e.g. “My heart beats really fast”); (f) Depression (ten items), which examines lack of energy, and feelings of guilt, sadness, and hopelessness (e.g. “I feel sad”); and (g) Sleep disturbance (three items), that inquires possible sleeping difficulties from a wellbeing perspective (e.g. “I wake up at dawn”). Items are answered by a 5-point likert scale which ranges from 0 = nothing to 4 = a lot.

- Personality Assessment Inventory-Adolescents (PAI-A; Cardenal, Ortiz Tallo, & Santamaría, 2012; Stover, de la Iglesia, Castro Solano, & Fernández Liporace, 2015; Morey, 2008). This instrument was designed to assess psychopathology in adolescents aged between 12 and 18. It is composed by 264 items that allow calculating several scales. For the purpose of this research, only some scales and subscales will be used: Paranoia, Obsessive-Compulsive (subscale of Anxiety Related Disorders), Anxiety, Aggression, Somatic Complaints, Depression and Stress. Local adaptation included the analysis of internal consistency by Cronbach’s alphas, and principal component analysis to study its dimensionality (Stover, de la Iglesia, Castro Solano, & Fernández Liporace, 2015).

Procedure

It was a non-randomized sample. All participants were volunteers and their parents had to sign an informed consent as a requirement. Data was gathered by trained psychology students from a university in Buenos Aires with senior researchers supervising their work.

The tested model proposed a first-order factorial structure where 50 observed elements (psychopathology symptoms) were loaded in seven clinical scales (see Figure 1). For the cross-validation analyses and invariance testing the software EQS 6.2 was used. Due to the categorical nature of the items (Likert scaled), the estimation method ran for both analyses was robust maximum likelihood, using the polychoric correlation matrix. This type of method and matrix are more appropriate when variables are ordinal and when there is evidence of high values of skewness and kurtosis (Freiberg Hoffmann, Stover, de la Iglesia, & Fernández Liporace, 2013; Muthén & Kaplan, 1985).

To test for model fit in the cross validation study, different indexes obtained by the robust method were examined: CFI (Comparative Fit Index), NFI (Normed Fit Index), IFI (Incremental Fit Index) and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation). CFI, NFI and IFI values are considered to be appropriate when they are above .90. RMSEA, on the other hand, should be below .05 (Byrne, 2006; Kline, 1998).

In order to analyze factorial invariance, hierarchical models with constrains were studied. MODEL 1 had no constraints, MODEL 2 constrained loadings, and MODEL 3 constrained loadings and covariances. This analysis was done twice: first, to test invariance between the female and male subsamples; and secondly, to test invariance between younger and older groups of adolescents (12-15 year olds vs. 16-18 year olds). Fit was assessed by the Satorra Bentler scaled statistic (S-B), CFI and RMSEA. Invariance was tested by the ΔS-B and the ΔCFI. The former was expected to be statistically no significant at a .05 alpha level, while the latter was expected to be lower than .01 (Byrne, 2006).

Finally, external criterion correlations were calculated with SPSS 18.0 and ordinal alphas were calculated with Excel following the procedure suggested by Elosúa and Zumbo (2008).

Results

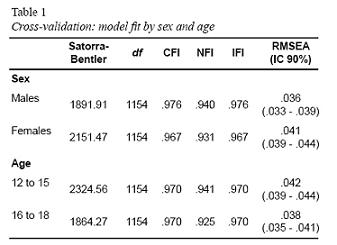

First, cross-validation analyses were conducted to test if the fit of the model prevailed in samples differentiated by sex and age. Thus, the male and the female subsamples were tested separately. As seen in Table 1, fit indexes showed to be an excellent fit for both groups. Model fit was also tested in two age samples: adolescents aged 12-15 years and 16-18 years. Again, fit indexes showed the appropriateness of the model (Table 1).

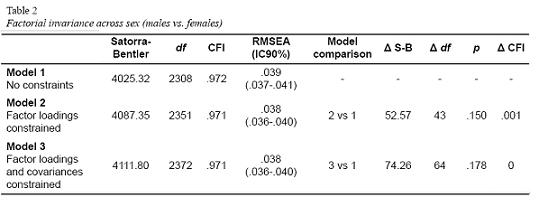

Additionally, hierarchical models with constrains were studied in order to analyse factorial invariance. To study invariance between the samples differentiated by sex, the fit was firstly tested in a model without constraints (MODEL 1). Both CFI and RMSEA values were adequate (see Table 2). A second model (MODEL 2) imposed constraints in all factor loadings. Again, model fit showed the expected values. The third and last model tested (MODEL 3) also imposed constraints in covariances. In this case, model fit was also correct.

Furthermore, Table 2 shows values for model comparison. The difference in the Satorra-Bentler scaled statistic (ΔS-B) corresponding to the comparison of MODEL 1 versus MODEL 2 was not significant at an alpha level of .05. Change in CFI was minimum (.001). In the case of the more constrained (MODEL 3), there was no significant change in the S-B scaled statistic (p > .05). Moreover, in this case, CFI showed no change in fit (invariance).

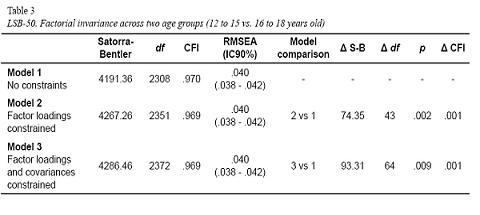

When testing for factorial invariance in groups compared by age, the same procedures were performed. That is, a model with no constraints was firstly tested (MODEL 1); then, factor loadings were imposed (MODEL 2); and finally, covariances were constrained (MODEL 3). CFI and RMSEA values were adequate in all cases (Table 3). Model comparison showed a significant statistical difference in the Satorra-Bentler scaled statistic between MODEL 1 and 2, and also between MODEL 1 and MODEL 3. In both cases, a change of .001 was found in the CFI.

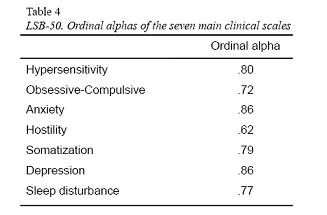

Then, considering that all items are responded in a Likert-type scale, ordinal alphas were calculated to study internal consistency. As seen in Table 4, all ordinal alphas indicate excellent internal consistency.

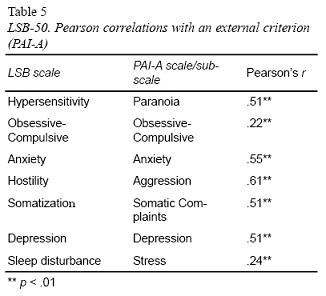

Finally, in order to obtain evidences of validity by external criterion, Pearson correlations were calculated between the clinical scales of the LSB-50 and their paires of the PAI-A. The association between the LSB-50’s Hypersensitivity scale and Paranoia was positive and moderate (r = .51; p < .001). The Obsession-Compulsion scale showed a positive but low correlation

(r = .22; p < .001) with the Obsessive-Compulsive subscale of the Anxiety Related Disorders (ARD) scale. The association between the Anxiety scales was positive and moderate

(r = .55; p < .001). Hostility had a positive and strong correlation with PAI-A’s Aggression scale (r = .61; p < .001). The correlation between Somatization and Somatic Complaints was also positive and moderate (r = .51; p < .001). The relation between the Depression scales was positive and moderate (r = .57; p < .001). And finally, Stress was chosen as the external criterion for Sleep disturbance. The result indicated that their association was positive and low (r = .24; p < .001) (Table 5).

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to study the psychometric properties of the LSB-50 (de Rivera & Abuín, 2012) in a sample of Argentinean adolescents. The results of the present study found support for the seven-factor structure in the cross-validation and factorial invariance. In the former, the model exhibited good fit in female and male samples as well as in the younger and older groups. Factorial invariance was found in all the proposed models, which entailed different restrictions of equivalency. However, the ΔS-B was statistically significant when studying invariance across the age, while the ΔCFI was minimal, indicating a good overall fit of all models (Byrne, 2006). Moreover, the goodness of fit was also reach at the level of the item, providing a more strict proof of construct validity than when the sum of scores are used as input values for factorization.

It is possible that the positive results of this study may rely on two issues. Firstly, as mentioned, the LSB-50 was carefully designed to overcome the alleged flaws of the SCL-90-R. The thorough examination of that instrument - considering results from globally conducted studies - may have had a positive impact in content validity and consequently positively affected the result of factorial analyses. Secondly, the analyses conducted in the present research contemplated the ordinal nature of the elements under study, using polychoric matrixes and robust methods in all cases. It is possible that this statistic decision also favoured the results obtained.

Finally, in regards to internal consistency, as stated, previous studies commonly used Cronbach’s alphas for its assessment. In general, psychopathology screening measures showed good results when using this procedure (e.g. Abuín & de Rivera, 2014; Caparrós Caparrós et al., 2007; Carrasco Ortíz et al., 2003; Casullo & Castro Solano, 1999; Ruipérez et al., 2001). However, Elosúa and Zumbo (2008) proposed the use of ordinal alphas as a more appropriate choice when scores are obtained in Likert scales. In this study, the ordinal alphas for the seven scales of the LSB-50 indicated good internal consistency.

Also, it was important to determine if the LSB-50’s clinical scales were correlated with a diagnostic measure as the PAI-A. As expected, mostly positive and moderate associations were found. The were some exceptions such as the Obsession-Compulsion and Sleep disturbance scales that showed positive but low correlations with the Obsessive-Compulsive subscale of ARD and the Stress scale, respectively.

In the case of Obsession-Compulsion, the weak association with the Obssessive-Compulsive subscale of ARD may be due to differences in the content of the items that form the scale. Despite having the same name, the LSB-50’s Obsession-Compulsion score refers to the presence of doubts and rituals or compulsions, while the PAI-A’s Obsessive-Compulsive subscale mostly refers to indecision, rigidity and perfectionism. Although both scales share the measurement of doubts/indecision, the remaining items cover different content, which certainly explains the weak but positive association between them.

As Sleep disturbance did not have an exact correlate in the PAI-A, the Stress scale was chosen as its external criterion. However, both scales do not measure the same construct. Notwithstanding, a positive correlation was expected between them as stressed individuals tend to also experience some sleep disturbance. The results obtained provide support to this assumption.

Regarding the limitations of the study, they are centred on two issues. Firstly, the sample was nonrandomized. Although this is a common practice within psychology researches, it might entail restrictions for the generalization of the results obtained. Secondly, the LSB-50 does not yet count with external validity evidence. Consequently, further studies should test this aspect and provide information about sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values, as well as Receiving Operating Characteristic curves to establish adequate cut-off values.

Previous research on the psychometric properties of other screening measures of psychopathology - such as the SCL-90, the SCL-90-R, the BSI, the BSI-18, and the SA-54 - provided little evidence of validity of a multidimensional model. Since those psychometric measures for screening psychopathology tend to show serious difficulties to demonstrate evidence of construct validity as well as separated scores for the proposed clinical scales (e.g. Benishek et al., 1998; Hardt et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2013; Ming-zhi et al. 2004; Rauter et al., 1996; Sandín et al., 2008; Schmitz et al., 2000; Vassend & Skrondal, 1999), rigorous factorial analyses result imperative for any new instrument that alleges to constitute an improvement of the former instruments. Cross-validation studies and the test of factorial invariance are among the strictest calculations for testing construct validity and proving the multidimensionality of a psychometric instrument. The Argentinean adaptation of the LSB-50 has shown evidence of construct validity and reliability. It should be highlighted that the robust statistics obtained support the calculation of seven separated clinical scales: Hypersensitivity, Obsession-Compulsion, Anxiety, Hostility, Somatization, Depression, and Sleep disturbance. Therefore, this scale is recommended for its use in research and applied psychological fields with Argentinean adolescents.

References

Abuín, M. R., & de Rivera, L. (2014). La medición de síntomas psicológicos y psicosomáticos: El Listado de Síntomas Breve (LSB-50). Clínica y Salud, 25, 131-141. doi: 10.1016/j.clysa.2014.06.001

Aroian, K. J., Patsdaughter, C. A., Levin, A., & Gianan, M. E. (1995). Use of the Brief Symptom Inventory to assess psychological distress in three immigrants groups. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 41(1), 31–46.

Alvarado, B. G., Sandín, B., Valdez-Medina, J. L., González-Arratia, N., & Rivera, S. (2012). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the SA-45 Questionnaire in a Mexican simple. Anales de Psicología, 28(2), 426-433. doi: 10.6018/analesps.28.2.148851

Angold, A., Costello, E.J., & Worthman, C.M. (1998). Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine, 28(1), 51-61.

Bados López, A., Balaguer, G., & Coronas, M. (2005). Qué mide realmente el SCL 90 R?: Estructura factorial en una muestra mixta de universitarios y pacientes. Psicología Conductual Revista Internacional de Psicología Clínica de la Salud, 13(2), 181-196.

Benishek, L. A., Hayes, C. M., Bieschke, K. J., & Stoffelmayr, B. E. (1998). Exploratory and confirmatory analyses of the Brief Symptom Inventory among substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse, 10(2), 103–114. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(99)80127-8

Bonynge, E. R. (1993). Unidimensionality of SCL-90-R scales in adult and adolescent crisis samples. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(2), 212–215. Doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199303)49:2<212::AID-JCLP2270490213>3.0.CO;2-V

Boulet, J., & Boss, M. W. (1991). Reliability and validity of the Brief Symptom Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(3), 433–437. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.433

Briggs, S. (2009). Risks and opportunities in adolescence: understanding adolescent mental health difficulties. Journal of Social Work Practice: Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community, 23(1), 49-64. doi: 10.1080/02650530902723316

Byrne, B. M. (2006). Structural Equation Modeling with EQS. Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Caparrós Caparrós, B., Villar-Hoz, E., Juan Ferrer, J., & Viñas-Poch, F. (2007). Symptom Check-List-90-R: Fiabilidad, datos normativos y estructura factorial en estudiantes universitarios. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7(3), 781-794.

Cardenal, V., Ortiz Tallo, M., & Santamaría, P. (2012). PAI-A. Inventario de evaluación de la personalidad para adolescentes. Manual de aplicación -Versión experimental. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Carrasco Ortiz, M. A., Sánchez Moral, V., Ciccotelli, H., & del Barrio, V. (2003). Listado De Síntomas SCL-90-R: Análisis de su Comportamiento en una Muestra Clínica. Acción Psicológica, 2(2), 149-161.

Casullo, M. M., & Castro Solano, A. (1999). Síntomas psicopatológicos en estudiantes adolescentes argentinos. Aportaciones del SCL-90. Anuario de Investigaciones, 7, 147-157.

Corcoran, K., & Fischer, J. (2000). Measures for Clinical Practice. A sourcebook. New York: The Free Press.

Cyr, J. J., McKenna-Foley, J. M., & Peacock, E. (1985). Factor structure of the SCL-90-R: Is there one? Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(6), 571-578. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4906_2

Daoud, F. S., & Abojedi, A. A. (2010). Equivalent factorial structure of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in clinical and nonclinical Jordanian populations. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 116-121. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000016)

Davison, M. L., Bershadsky, B., Bieber, J., Silversmith, D., Maruish, M. E., & Kane, R. L. (1997). Development of a brief, multidimensional, self-report instrument for treatment outcomes assessment in psychiatric settings: Preliminary findings. Assessment, 4(3), 259-276.

de la Iglesia, G., Fernández Liporace, M., & Castro Solano, A. (2015). Psychometric study of the main clinical scales of the Listado de Síntomas Breve (LSB-50) -Short Checklist of Symptoms- in Argentinean adolescents. Manuscript submitted for publication.

de la Iglesia, G., Castro Solano, A., & Fernández Liporace, M. (2015, in press). Adaptación del PAI-A en población de adolescentes argentinos. En Santamaría Fernández, P. (Ed.), Adaptación del Inventario de Evaluación de la Personalidad (PAI-A) en población Argentina. Madrid: TEA.

De Las Cuevas, C., Gonzalez De Rivera, J. L., Henry Benitez, M., Monterrey, A. L., Rodriguez-Pulido, F., & Gracia Marco, R. (1991). Análisis factorial de la versión española del SCL-90-R en la población general Anales de psiquiatría, 7(3), 93-96.

de Rivera, L., & Abuín, M. L. (2012). LSB-50 Listado de Síntomas Breve: Manual. España: TEA Ediciones.

Derogatis, L. R. (1975). Brief Symptom Inventory. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research.

Derogatis, L. R. (1983). SCL–90–R: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual II. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research.

Derogatis, L. R. (2001). The Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI 18). Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson, Inc.

Derogatis, L. R., & Spencer, M. S. (1982). The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit.

Eaton, W. W., Neufeld, K., Chen, L., & Cai, G. (2000). A comparison of self-report and clinical diagnostic interviews for depression: Diagnostic Interview Schedule and Schedules for Clinical assessment in Neuropsychiatry in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment area follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(3), 217-222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.217

Elosúa, P., & Zumbo, B. D. (2008). Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada Psicothema, 20(4), 896-901.

Freiberg Hoffmann, A., Stover, J. B., de la Iglesia, G., & Fernández Liporace, M. (2013). Correlaciones Policóricas y Tetracóricas en Estudios Exploratorios y Confirmatorios. Ciencias Psicológicas, 7(2), 151-164.

Graham, P. (2004). EOA: The End of Adolescence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grande, T. L. (2014). Path analysis of the SCL-90-R: Exploring use in outpatient assessment. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0748175614538061.

Hardt, J., Gerbershagen, H. U., & Franke, P. (2000). The symptom checklist, SCL-90-R: Its use and characteristics in chronic pain patients. European Journal of Pain, 4(2), 137-148. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0162

Helgeland, M.I., Kjelsberg, E., & Torgersen, S. (2005). Continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1941–1947.

Hernández-Aguado, I., Gil de Miguel, A., Delgado Rodriguez, M., Bolúmar Montrull, F., Benavides, F. G., Porta Serra, M., Álvarez-Dardet Díaz, C., Vioque López, J. ... Lumbrera Lacarra, B. (2011). Manual de Epidemiología y Salud Pública para grados en Ciencias de la Salud (2ª ed.). Madrid: Médica Panamericana.

Hoffmann, N. G., & Overall, P. B. (1978). Factor Structure of the SCL-90 in a Psychiatric Population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46(6), 1187-1191. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.46.6.1187

Holi, M. (2003). Assessment of psychiatric symptoms using the SCL-90 (Doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychiatry, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland). Retrieved from http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/laa/kliin/vk/holi/assessme.pdf

Jessor, R. (1987). Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. British Journal of Addiction, 82(4), 331-342. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01490.x

Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12(8), 597-605.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kofler, M.J., Rapport, M.D., Bolden, J., Sarver, D.E., Raiker, J.S., & Alderson, R.M. (2011). Working memory deficits and social problems in children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(6), 805-817.

Kohn, R., Levav, I., Caldas de Almeida, J. M., Vicente, B., Andrade, L., Caraveo-Anduaga, J. J., Saxena, S., & Saraceno, B. (2005). Los trastornos mentales en América Latina y el Caribe: Asunto prioritario para la salud pública Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 18 (4/5), 229-240.

Lewis, G., Sheringham, J., Kalim, K., & Crayford, T. (2008). Mastering Public Health: A postgraduate guide to examinations and revalidation: A Guide to Examinations and Revalidation. Londres: Royal Society of Medicine Press.

Liu, Z., Chen, H., Cao, B., & Jiao, F. (2013). Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Brief Symptom Inventory in high school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21(1), 32-34.

Loutsiou-Ladd, A., Panayiotou, G., & Kokkinos, C. M. (2008). A review of the factorial structure of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Greek evidence. International Journal of Testing, 8(1), 90-110. doi:10.1080/15305050701808680

Martínez Azumendi, O., Fernández Gómez, C., & Beitía Fernández, M. (2001). Variabilidad factorial del SCL-90-R en una muestra psiquiátrica ambulatoria. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 29(2), 95-102.

Ministerio de Salud (2010). Estimación de la población afectada de 15 años y más por trastornos mentales y adicciones. Retrieved from http://www.inclusionmental.com.ar/contents/biblioteca/1329413814_–estimacion–de–la–poblacion–afectada–por–salud–mental–arg.pdf

Ming-zhi, X., Heng-fen, L., & Huei-fang, Z. (2004). Factorial Structure of the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) in College Students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 12(4), 2004, 348-351.

Morey, L. C. (2008). Personality Assessment Inventory - Adolescent (PAI-A). Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc.

Muthen, B., & Kaplan, D. (1985). A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38, 171-189.

Piersma, H. L., Boes, J. L., & Reaume, W. M. (1994). Unidimensionality of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in adult and adolescent inpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63(2), 338-344. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6302_12

Prunas, A., Sarno, I., Preti, E., Madeddu, F., & Perugini, M. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R: A study on a large community sample. European Psychiatry, 27(8), 591-597. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.12.006

Quiroga, C.V., Janosz, M., Bisset, S., Morin, A.J.S. (2013). Early Adolescent Depression Symptoms and School Dropout: Mediating Processes Involving Self-Reported Academic Competence and Achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 552-560.

Rauter, U. K., Leonard, C. E., & Swett, C. P. (1996). SCL-90-R factor structure in an acute, involuntary, adult psychiatric inpatient sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52(6), 625-629. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199611)52:6<625::AID-JCLP4>3.0.CO;2-J

Rojas Gualdrón, D. F. (2012). Capacidad Explicativa de los Síntomas del LSB-50 sobre un Único Factor de Psicopatología General Presented at the I Congreso Internacional de Psicología: Investigación y Responsabilidad Social, Bucaramanga, Colombia.

Ruipérez, M. A., Ibáñez, M. I., Lorente, E., Moro, M., & Ortet, G. (2001). Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the BSI: Contributions to the Relationship Between Personality and Psychopathology. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17(3), 241–250. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.17.3.241

Sandín, B., Valiente, R. M., Chorot, P., Santed M. A., & Lostao, L. (2008). SA-45: forma abreviada del SCL-90 Psicothema, 20(2), 290-296.

Schmitz, N., Hartkamp, N., Kiuse, J., Franke, G. H., Reister, G., & Tress, W. (2000). The Symptom Check-List-90-R (SCL-90-R): A German validation study. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 9(2), 185-193. doi: 10.1023/A:1008931926181

Stepp, S.D., Olino, T.M., Klein, D.N., Seeley, J.R., & Lewinsohn, P.M. (2013). Unique influences of adolescent antecedents on adult borderline personality disorder features. Personality Disorders, 4(3), 223-229. doi: 10.1037/per0000015

Stover, J. B., de la Iglesia, G., Castro Solano, A., & Fernández Liporace, M. (2015). Inventario de Evaluación de la Personalidad para adolescentes: Consistencia interna y dimensionalidad en adolescentes de Buenos Aires. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Torres, L., Miller, M. J., & Moore, K. M. (2013). Factorial Invariance of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) for Adults of Mexican Descent Across Nativity Status, Language Format, and Gender. Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 300–305. doi: 10.1037/a0030436

Urbán, R., Kun, B., Farkas, J., Paksi, B., Kökönyei, G., Unoka, Z., Felvinczi, K., Oláh, A., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Bifactor structural model of symptom checklists: SCL-90-R and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in a non-clinical community sample. Psychiatry Research, 216(1), 146-154. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.027

Vassend, O., & Skrondal, A. (1999). The problem of structural indeterminacy in multidimensional symptom report instruments. The case of SCL-90-R. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(7), 685-701. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00182-X

Vrouva, I., Fonagy, P., Fearon, P.R., & Roussow, T. (2010). The risk-taking and self-harm inventory for adolescents: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychological Assessment, 22(4), 852-865. doi: 10.1037/a0020583

Zack, M., Toneatto, T., & Streiner, D. L. (1998). The SCL-90 factor structure in comorbid substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse, 10(1), 1998, 85-101. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(99)80143-6

Zhang, J., & Zhang, X. (2013). Chinese college students’ SCL-90 scores and their relations to the college performance. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(2), 134-140. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.09.009

Para citar este artículo:

de la Iglesia, G., Castro Solano, A., & Fernández Liporace, M. (2016). Evidence of validity of the LSB-50: cross-validation, factorial invariance and external criterion analysis. Ciencias Psicológicas, 10(1), 63-73.