Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Related links

Share

CLEI Electronic Journal

On-line version ISSN 0717-5000

CLEIej vol.16 no.1 Montevideo Apr. 2013

Relevant Organizational Values in the Implementation of Software Process Improvement Initiatives

Odette Mestrinho Passos, Arilo Claudio Dias-Neto, Raimundo da Silva Barreto

Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), Institute of Computing (IComp)

Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil, 69077-000

odette@ufam.edu.br, {arilo,rbarreto}@icomp.ufam.edu.br

Abstract

In a globalized world, organizational culture plays an important role in companies since it represents one of the main factors of business success in competitive scenarios. Organizational culture is defined by a set of attitudes, behaviors, norms and beliefs that may guide the life of a company. Organizational values can ensure a common understanding among everyone in the organization, provided that they are shared by all their members. This study describes the results of a systematic literature review on typological model of organizational culture in order to identify organizational values for characterizing the organizational culture in a company. Additionally, we managed a survey to researchers and practitioners analyzing which organizational values are most relevant to a software organization involved with a software process improvement (SPI) initiative. In this paper, we describe forty organizational values identified in the systematic review, and we give particular emphasis in the values the survey results indicate as the main ones that influence the adoption/maintenance of SPI initiatives, i.e., (i) being committed to a high-quality policy for products, services, and processes; (ii) having a well-defined and established vision and goals; and (iii) imposing responsibilities on the team members for meeting deadlines and achieving goals.

Portuguese abstract

Em um mundo globalizado, a cultura organizacional desempenha um papel importante nas empresas, uma vez que representa um dos principais fatores de sucesso dos negócios em cenários competitivos. A cultura organizacional é definida por um conjunto de atitudes, comportamentos, normas e crenças que guiam a vida de uma empresa. Valores organizacionais podem garantir um entendimento comum de todos na organização, desde que sejam compartilhados por todos os seus membros. Este trabalho descreve os resultados de uma revisão sistemática da literatura sobre modelos de tipologias para análise da cultura organizacional com o objetivo de identificar os valores organizacionais que caracterizam a cultura organizacional de uma empresa. Além disso, realizamos um survey com pesquisadores e praticantes da indústria de software sobre quais valores organizacionais são mais relevantes para uma organização de software que esteja envolvida com um iniciativa de melhoria de processo de software. Neste artigo, descrevemos 40 valores organizacionais identificados na revisão sistemática e damos ênfase especial nos principais valores indicados pelo resultado do survey que influenciam a adopção/manutenção de iniciativas de MPS, isto é, (i) ter uma política de compromisso com a qualidade dos produtos, serviços e processos; (ii) ter a visão, metas e objetivos claros e estabelecidos; e (iii) exigir que os membros tenham responsabilidades quanto a prazos e metas.

Keywords: Organizational Culture, Organizational Values, Software Process Improvement, Survey, Systematic Literature Review, Typological Model.

Portuguese Keywords: Cultura Organizacional, Valores Organizacionais, Melhoria de Processo de Software, Survey, Revisão Sistemática da Literatura, Modelo de Tipologia.

Received: 9/7/2012 Revised: 13/12/2012 Accepted: 29/12/2012

1. Introduction

In recent years, many software companies have invested in software process improvement (SPI) initiatives to ensure their survival in an increasingly competitive world with ever more demanding customers. These programs consist of a sequence of steps to ensure that the development process will deliver excellence in product quality (1) (2). However, the adoption of these programs alone often do not ensure software quality, as social, human, and cultural aspects are, usually, not considered by these programs.

Some studies indicate that organizational culture (which will be referred to a OC in this paper) is one factor that can influence the way professionals respond to SPI initiatives (1)(3)(4)(5). OC also helps to explain an organization’s success or failure in implementing such initiatives, as well as its implication for the motivation and performance of their employees (1)(3)(5).

OC is a subject that has received only scant attention in scientific reserach. Even though the cultural assumptions underlying some maturity models have been the subject of study, the impact of workplace culture, i.e. OC, on SPI efforts has not been thoroughly examined (5).

Hofstede (6) regarded OC as the collection of values, beliefs and norms shared by its members and reflected in its practices and goals. We adopt the definition presented in (7), where the authors state that OC refers to “a value (features) system shared by members of an organization that distinguish it from others”. OC has generated enormous interest in business and therefore it is necessary to identify the cultural profiles of organizations. A step in this direction is the study and classification of the organizational values, which are the fundamental core of OC (8).

Organizational values (which will be referred to a OV in this paper) can be defined as the beliefs held by an individual or group regarding means and purposes that an organization ought to identify in its management, in choosing what business actions or objectives are preferable to alternative actions, or in establishing organizational objectives (9). Values define a social institution, and norms, symbols, rituals and other cultural activities around them (9). OV become embedded within organizations, providing organizations the characteristic of stability which is similar to individual and societal values (10). They are an essential component of OC (11) and define what is important to a group (1).

The top managers should have knowledge of OV to achieve desired organizational goals contributing to the competitive success of an organization and providing the company a significant strategic advantage over other competitors (12). The identification of the OV is a critical step since it will affect the behavior of members of an organization. Therefore, the organizations should be aware of their OV in order to meet their objectives. The OV is a contributing factor to an organization’s success in the market and gives the company a significant strategic advantage over its competitors. Good fit between the values embedded in the software development process and the overall organization’s values lead to a more successful implementation of SPI initiatives (1) (3). Software managers and SPI agents are advised to reorganize the SPI initiative to better accommodate cultural variation within the organization (3).

Based on this scenario, we decided to investigate how OC could influence the success/failure of an SPI initiative. To achieve results with scientific value, we followed a methodology based on empirical studies (13). As the first step, we conducted a systematic literature review aimed to identify, analyze and evaluate the typological models for analysis of OC, and to extract the relevant OV among each type of OC from selected models. The application of a systematic review requires following a well-defined and sequential set of steps, according to an appropriately developed research protocol (14). This protocol is designed considering a specific theme representing the central element of the investigation. The steps of the research, the strategies set out to collect the evidence, and the focus of the research questions are explicitly defined, so that other researchers can reproduce the same research protocol, and also to judge the adequacy of the standards adopted in the study (5).

After the identification of these OV, we conducted a primary study – survey (as presented in (13)) – to identify which OV extracted from typological models are important to characterize the OC in a software organization from the viewpoint of researchers and practitioners involved with SPI. Moreover, we analyzed the level of relevance of each organizational value for a software organization involved in the implementation of an SPI initiative.

This paper describes the results obtained from these two initial studies (systematic review and survey) with emphasis on identifying the OV that are most relevant for the adoption and implementation of SPI initiatives by software organizations.

The text is organized into five sections, including this introduction. Section 2 describes the typological models for analyzing OC utilized for the extraction of the OV, indentified from a systematic review. Section 3 discusses the relevance of the OV for the success of SPI initiatives, according to the opinion of surveyed software engineers. Section 4 compares the results of our studies with related studies. Finally, Section 5 presents our final considerations and implications for future work.

2. Systematic Review to Identify Typological Models and Organizational Values

A systematic review “is an instrument to identify, evaluate and interpret all available research and relevant information on a research question, a topic or phenomenon of interest, and has as the main aim to provide a fair assessment of a research topic, using a reliable, rigorous, and auditable methodology” (14).

A systematic review requires considerable effort compared to an informal literature review. While the literature review is conducted on an informal ad-hoc basis, usually driven by personal interests of researchers, without planning and selection criteria established a priori, a systematic review follows a formal protocol to conduct research on a particular theme, and a well-defined sequence of methodological steps (16).

The process for conducting a systematic review involves three main phases, as listed below (16). In our work, we conducted a systematic review according to technical reports published in (15)(14).

-

Planning the Review: The research objectives are listed and the protocol of the review is defined;

-

Conducting the Review: The sources for the systematic review are selected, the primary studies are identified, selected, and evaluated according to the criteria for inclusion, exclusion, and quality protocol established during the review;

-

Reporting the Review: The study data are extracted and synthesized to be published.

2.1 Planning the Systematic Review

The objectives of this study are (i) identifying the types of typological models in the technical literature for analysis of OC; and (ii) extracting the main values addressed by the identified models. We sought answers to two questions:

Q1: What typological models for analysis of OC are available in the technical literature?

Q2: What are the OV described as important elements to characterize the OC by the identified models?

The publications were accessed by digital libraries using their respective search engines. Such publications are not restricted to the area of computing since OC is an aspect shared in several fields such as social sciences and humanities, life sciences, physical sciences and engineering.

The sources used in this systematic review were international digital libraries (Scopus, ScienceDirect, Emerald, and Ebsco) and Brazilian digital libraries (Journal of Business Administration - RAE and Brazilian Administration Review - BAR). In addition to this, we also included as sources one paper and seven books that are relevant to the topic of OC:

-

Paper 1: Hofstede, G.; Neuijen, B.; Ohayv, D.; Sanders, G. Measuring Organizational Cultures: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study Across Twenty Cases. Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 286-316, 1990.

-

Book 1: Carvalho, C.; Ronchi, C. Cultura Organizacional: Teoria e Pesquisa. Rio de Janeiro: Fundo de Cultura, 2005 (in Portuguese).

-

Book 2: Dias, R. Cultura Organizacional. Campinas: Alínea, 2003 (in Portuguese).

-

Book 3: Fleury, M.; Fischer, R. (Org). Cultura e Poder nas Organizações. 2nd ed., São Paulo: Atlas, 2007 (in Portuguese).

-

Book 4: Freitas, M. Cultura Organizacional: Formação, Tipologias e Impactos. São Paulo: Makron, McGraw-Hill, 1991 (in Portuguese).

-

Book 5: Motta, F.; Caldas, M. Cultura Organizacional e Cultura Brasileira. São Paulo: Atlas, 1997 (in Portuguese).

-

Book 6: Robbins, S. Organizational Behavior. 11th ed., New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Pearson Education, 2005.

-

Book 7: Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 3rd ed., San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2004.

We restricted the search by using specific keywords to find publications of interest. As this study represents a mapping study (characterizing a field), the search string was defined according to two aspects (Population and Intervention (17)) , as in the structure below:

-

Population: works that describe results regarding organizational culture (and synonym) :

-

Keywords: "organizational culture" OR "organisational culture" OR "culture profile" OR "organizational change" OR "organisational change" OR "organizational behavior" OR "organisational behavior" OR "organizational change management" OR "organisational change management" OR "subculture"

-

Intervention: typological model for analysis of organizational culture:

-

Keywords: "model" OR "template" OR "framework" OR "type" OR "method" OR "methodology" OR "strategy" OR "analysis"

2.2 Conducting the Systematic Review

A systematic review was done between January 2011 and February 2011 and the publications were selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria established during the review protocol. Duplicated publications and those not available on the Internet were excluded. In addition, we excluded publications that clearly dealt with other matters not relevant to the research.

In an intitial analysis, we analyzed the title, abstract and keywords. If we found relevance to the research topic, the publication was pre-selected. In a second analysis, we analyzed the full-paper, extracting the OV described by the typological models.

2.3 Reporting the Systematic Review

Initially, we identified 861 papers/books that discussed OC. After the first analysis, we selected 178 studies for the second stage (full-paper analysis), being 171 papers and 7 books. Table 1 shows the consolidated distribution of works. Thus, after reading all 178 studies, we identified 36 models for analysis of OC (Table 2).

During the search, three similar models were verified: i) Competing Values Model (CVM), ii) Competing Values Approach (CVA) and iii) Competing Values Framework (CVF), authors Robert Quinn, John Rohrbaugh, John Kimberly, Michael McGrath, and Kim Cameron, where the latter is an evolution of the first two, and therefore distinctions between them will not be made in this report. We will refer to only the model of Cameron and Quinn (18) called the Competing Values Framework (CVF). Likewise, the model of Denison and Mishra (19) is similar to the model of Denison (20). Therefore it will be simply referred to as Denison’s model.

Table 1: General results of the number of identified publications

Hofstede’s model (6)(20) is related to the analysis of national culture, but in many studies, it has been employed to assess OC. The model of Hofstede et al. (8) is specifically used for the analysis of OC. Thus, no distinctions are made between these models, as both are used to analyze the OC of an organization.

Table 2: Overall results of the identified models’s authors

As can be seen, 36 models were identified. From this list, seven models (see Table 3) were selected according to the following criteria:

-

CRI1: access to the paper/book that describes the complete model;

-

CRI2: description of an empirical validation in research on OC;

-

CRI3: presentation of detailed definition regarding the characteristics (values) of the typologies listed by model;

-

CRI4: the method of evaluation to achieve the typologies of OC in a company should be suitable for quantitative research;

-

CRI5: explicit description of the quantitative method used to achieve the typological models in order to emphasize the OV.

The model of Schein (11) was not selected because it is not based on typologies but on a set of assumptions that he called cultural dimensions: (1) assumptions about issues of external adaptation; (2) assumptions about the management of internal integration; (3) deeper cultural assumptions about reality and truth; (4) assumptions about the nature of time and space; and (5) assumptions about the nature, activity and human relationships.

Importantly, the references for the study of OV were extracted directly from the authors of the selected models, thus avoiding the problem of opinion/comments of others. Organizational values were extracted from the definition of typological characteristics listed for each selected model, and the description of the quantitative method used to achieve this typology. Therefore, it was so important that the reading of the references of the models were from the author who developed it.

The OV were classified into three categories representing the type of professional in the organization responsible for the implementation of each value (22). The categories defined were:

-

Top Manager: representing the top management and directors;

-

Project Leader: representing project managers and team leader;

-

Developer: representing the project’s technical team (designers, testers, programmers and analysts).

Table 3: Selected models for the extraction of OV

The classification of OV in categories was based in reading the definition of typological characteristics which suggest the class in which the OV is associated, for example, work groups, leaders, founders, managers and organization. These classes were adapted to the specific professional type that works in a software organization, as top manager, project leader, and developer. Moreover, we distributed the OV in accordance with our analysis of keywords indicating who is the professional responsible for their implementation in a software organization.

From the total, we selected 40 OV. Of the 40 values, 20 (50%) were attributed to the category of top manager, 7 (17%) to the category of project leader and 13 (33%) to the category of developer. Table 4 lists the OV according to the model they were extracted from.

The model of Cameron and Quinn (18) approached 65% of the values identified, while the models of Handy (23) and Denison (20) approached 32.5%. This shows that the model of Cameron and Quinn (18) covers many of the values found by this systematic review in addition to being among the most cited research on OC.

The model of Schein (11), although one of the most cited in the technical literature, was not selected to be part of this research. The reason is due to the fact that its method for collecting data on the type of OC is clinical research, which according to Schein (11), requires the researcher's presence and involvement in the organization and therefore it is a qualitative method.

Table 4: List of OV extracted from the models

Based on the results obtained in this systematic review, a survey was carried out aimed at identifying the importance of each identified organizational value to characterize OC in a software organization, and their level of relevance for a software organization involved in an SPI initiative. The next Section describes in detail the planning and the results obtained in this study.

3. Survey to Assess the Relevance of Organizational Values for the Success of SPI Initiatives

The goal of this survey is to analyze which OV are important to define the OC of a software organization and the level of relevance of each organizational value for a software organization involved in an SPI initiative.

This study was designed from the structure proposed by the GQM paradigm as follows:

-

Analyze an initial set of OV extracted from typological models that analyze the OC of a company.

-

With the purpose of characterizing them.

-

With respect to their importance to characterize a model of OC for a software organization and their relevance to the implementation of SPI initiatives.

-

From the point of view of project leader and manager, developer, outside consultants and assessors of SPI initiatives.

-

In the context of software organizations implementing an SPI initiative.

The survey was carried out in two main phases: (i) Planning and Executing the Survey: subjects selection and questionnaire definition, and (ii) Reporting the Survey: the study data was extracted and synthesized to be published.

3.1 Planning and Execution the Survey

The survey population was comprised of software engineers who work or have worked in software organizations that (i) are starting, (ii) initiated, or (iii) are evaluated in SPI initiatives, represented by:

-

Software organization, through their directors, project leader and developer;

-

Outside consultants;

-

Assessors of SPI initiatives.

They had been chosen from a list issued by SOFTEX (Association for Promoting Brazilian Software Excellence – in Portuguese “Associação para a Promoção da Excelência do Software Brasileiro”). This association authorizes institutions to assess or implement the MPS.Br program in organizations that have implemented the Reference Model MR-MPS (28) and maintains a list of businesses and professionals that offer consulting services on SPI.

An online questionnaire was developed (in Portuguese) as an instrumentation of this study. Thus, the subjects could answer it using the Internet. There are five steps to complete the questionnaire:

-

Log-in screen: screen where the subject confirms his/her identity in the online questionnaire;

-

Characterization of the knowledge and skills of the subjects: in this step, the subject is asked about his/her personal data (name, e-mail, institution/organization and country), level of experience in implementing SPI initiatives, the time working with SPI initiatives, the number of organizations in which the participant has supported the implementation of such initiatives, academic background, the kind of participation in the implementation of SPI initiatives and, finally, which SPI initiatives the participant has worked with;

-

Identification of the importance of OV to characterize the OC in software organizations: for each organizational value, the subject should indicate whether it is important to characterize the OC in software organizations. In addition, the subject may include additional OV that he/she considers important and were not included in the initial set;

-

Definition of the level of relevance of each organizational value during the implementation of SPI initiative in a software organization: in this step, the organizational value indicated by subjects as important in step 3 are analyzed. Six levels of relevance were defined using a Likert scale:

(0) No Relevance: the lowest level of relevance. This means that the organizational value would have no influence on the success of a software organization implementing an SPI program;

(1) Very Low Relevance: This indicates the organizational value would not significantly affect a software organization involved with an SPI program;

(2) Low Relevance: This indicates the OV could be more relevant in some particular scenario, but in general the organization is not affected in the absence of this value;

(3) Medium Relevance: This indicates the organizational value has considerable impact when implementing an SPI program in a software organization, that is, the organization in certain projects would be affected in the absence of this value;

(4) High Relevance: This indicates the organizational value must be considered during the implementation of an SPI program in a software organization. It could be unnecessary only in a restricted number of particular scenarios;

(5) Very High Relevance: This indicates the organizational value is absolutely necessary to be considered during the implementation of an SPI program in a software organization. Absence of this value in software organizations may make the application of SPI programs unfeasible.

-

Thanks screen: screen where researchers thank the subjects for his/her participation.

3.1.1 Analysis Procedures Subjects Weight

For data analysis, the subject was not individually examined and, therefore, they have a different weight according to their level knowledge and skill. Researchers with higher experience level or skills must have a greater weight.

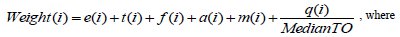

The mathematical formula used to define the subject’s weight was based on the proposal of a survey (29), and it has been adapted for this study. The formula to define subject’s weight is:

-

Weight (i) is the weight assigned for subject i;

-

e(i) is the subject’s experience level. The options for this field are: [0] = low; [1] = medium; [2] = high; [3] = excellent.

-

t (i) is work experience with SPI initiatives. The options for this field are: [0] = less than 1 year; [1] = between 1 and 2 years; [2] = between 3 and 5 years; [3] = between 6 and 10 years; [4] = more than 10 years.

-

f(i) is academic education. The options for this field are: [0] = high school or undergraduate; [1] = graduate degree; [2] = specialization degree; [3] = masters degree; [4] = PhD or DSc degree.

-

a(i) is the number of different roles assumed by the subject previously during the implementation of SPI initiatives, that could be: part of the internal team (such as top manager, project leader and developer), outside consultants, and/or assessors of SPI initiatives.

-

m(i) is the number of maturity models that the subject has applied (MPS-Br, CMMI, PMBOK, ISO 15504, ISO 12207 and others).

-

q(i) is the total number (estimated) of organizations that subject has supported in the implementation of SPI initiatives;

-

MedianTO is the median of the total number of organizations that subjects have supported in the implementation of SPI initiatives.

3.1.2 Analysis Procedures of Organizational Values

Identification of the Importance of Organizational Values

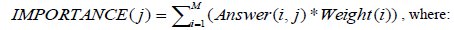

In order to define which OV are important to characterize the OC of a software organization, it is necessary, first, to sum the answer of all subjects (multiplying it by its respective weight).

-

IMPORTANCE(j) is the total organizational value of the answers of all subjects (multiplied by their respective weight);

-

Answer(i,j) is the indicator or importance (1) or not (0) defined by the subject i for the organizational value j;

-

Weight(i) is the weight attributed to the subject i;

-

M is the total of subjects that have participated in the survey.

Identification of the Relevance Level of Organizational Values

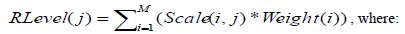

To define the level of relevance of organizational value classified previously as “important”, it is first necessary to sum the answer of each subject (multiplied by its respective weight). The formula is:

-

RLevel(j) is the total organizational value of the answer of all subjects (multiplied by their weight) for the organizational value j;

-

Scale(i,j) is the level of relevance scale (0-5) defined by the subject i for the organizational value j;

-

Weight(i) is the weight attributed to the subject i;

-

M is the total of subjects that have participated in the survey.

After this step, the OV were ordered from higher to the lower. The more relevant OV will be the one with the higher value for RLevel(j).

3.2 Reporting Survey Results

In total, 173 researchers and professionals in the industry were invited to take part in the survey. Of these, 41 answered the survey, which indicates a confidence level of around 87% for the collected data, using the formula described in Hamburg (30) .

3.2.1 Analysis of the Subject’s Characteristics

Table 5 shows the subjects’ characterization, including the weight, Formula (1), previously calculated for each subject. The subjects’ answers were analyzed for each organizational value, and thus provided the final result of the level of relevance of all OV.

Table 5: Subject’s characterization

Considering the profile of the participants that answered the survey we can say that:

-

Expertise Level: 42% of the participants were characterized as having "high" expertise related to the implementation of SPI initiatives;

-

Education: 44% of the participants have an Masters degree, and 20% have a PhD. degree;

-

Knowledge: 78% of participants have already been involved in the implementation of at least one SPI initiative. Specifically, 22% have attended one SPI initiative; 20% have attended two initiatives; 22% have attended three initiatives; and 15% have been involved with four or more SPI initiatives;

-

Industry Background: 51% of the participants have over 10 years of participation in the industry with SPI initiatives.

Although all participants were Brazilian software engineers, we believe that this fact does not invalidate our results or diminish their relevance, since they give a national perspective on the subject. In addition, 71% of the respondents have experience in implementing the CMMI, which is an international SPI model. We are also planning the extension of this survey to researchers and industry professionals from other sites around the world.

3.2.2 Analysis of the Importance of Organizational Values

After calculating the subject’s weights, we analyzed the importance of OV to characterize the OC of software organizations. There is not enough space to present all answers of all subjects; therefore, we present only the results obtained after the statistical data analysis. Applying the mathematical formula (2), we obtained the results shown in Table 6.

The obtained data indicated that there are five more important VO (100% of level of importance) to characterize the OC in a software organization. Firstly, the leader/manager project should adequately notify employees about decisions that may affect their work and ensure that they have access to this information. Moreover, it would be essential for a software organization to define a quality policy for its products, services and processes, including providing a salary according to an employee’s position, as well as clarify its perspectives and goals. The results also indicate that the team members should have commitment to deadlines and goals in a software project.

As seen in Table 6 , the organizational value “results and profits” with importance level of 122.0 (23.4%) is very distant from other values. This difference suggests this value has low importance to a software organization compared to the other values.

Table 6: Evaluation of the OV’s importance level

In addition to the OV included in the initial set, eleven new OV were added to the final set. They were indicated by some subjects, according to Table 7.

Table 7: New OV suggested by the subjects

After identifying the OV considered important by the subject, the next step is the definition of their level of relevance for a software organization involved with an SPI initiative, that is, the weight of each organizational value for a software organization involved with an SPI initiative. Applying the mathematical Formula (3) to the calculation of the level of relevance, we obtained the results shown in Table 8.

Table 8: Relevance evaluation of OV

Analyzing which OV would be more relevant to support the implementation/evaluation to SPI initiatives, according to the subject’s opinion, the main values would be for the top managers: (i) having a commitment to the quality policy for products, services and processes, (ii) establishing a vision, goals, and objectives clear and well-established, and (iii) monitoring of planned activities. In addition, the team members must have responsibilities with deadlines and goals for the project and have an involvement, commitment and participation in the final result. This last organizational value, according to the subjects’ opinions, is one the most relevant to the implementation/evaluation to SPI initiatives (with 87.6%) and one of the most important for charactering and achieving success in a software organization (96.6%). For the eleven new OV suggested by the subjects, a level of relevance was also indicated, as presented in Table 9.

Table 9: Relevance Level of OV suggested by the subjects

3.2.4 Analysis of Importance x Relevance of Organizational Values

General Analysis of Organizational Values

We can observe in the results that the OV obtained different classification considering their importance and relevance analysis. Table 10 provides a comparison between the order of importance x relevance for each organizational value.

These results obtained in this survey are very similar to the results published in Rocha et al. , which described the planning and execution of a survey that analyzed the experience of software engineers regarding the difficulties and success factors using the SPI programs MR-MPS and CMMI in small, medium and large software organizations. The results indicated the more typical factor in a successful implementation of SPI initiative is related to organization of employees and top management.

Observing Table 10, the OV (i) commitment to the quality policy for products, services and processes, (ii) clear and well-established vision, goals, and objectives and (iii) commitment to deadlines and goals, are among the five top OV most significant in order of importance and order of relevance.

Analyzing the results, they indicate that the OV “salary appropriate to the position” and “information on decisions” are very important for the characterization of a software organization. However, they would not be so relevant for the success of an SPI initiative implementation in a software organization. On the other hand, the OV “cooperation and collaboration” and “strategic management plan” are among the ten OV more relevant to the success of an SPI initiative implementation in a software organization, but they are not listed among the most important OV to characterize a software organization.

This difference in order could be due to many factors; for instance, in an SPI initiative, the subjects’ opinion, employees’ commitment and a strategic management plan are more relevant than a salary appropriate to the employee’s positions.

Analysis of Organizational Values per Category

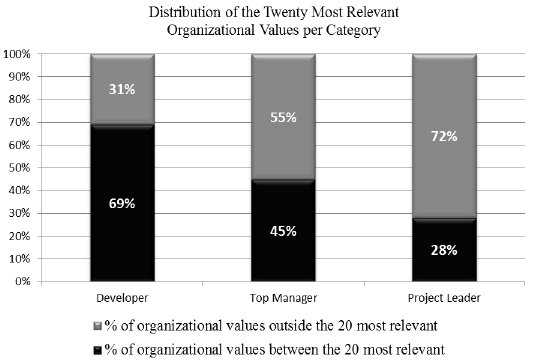

Observing Table 4 , we assigned a category to each organizational value as a way to specify who is responsible to implement such OV in a company. Evaluating in Table 10 the distribution of the 20 most relevant OV by category, representing 50% of all evaluated values, we find that 9 are related to category developer, 9 other OV are related to category top manager and only 2 OV are related to category project leader, as shown in Figure 1. The same result can be observed for the 20 most important.

This scenario suggests the commitment of the top managers in the implementation of an SPI initiative is insufficient for achieving success in this initiative. The contribution of the development team is also very important to reach the organization’s goal.

Thus, in order to complement this analysis, we evaluated the distribution of the 20 most relevant OV by the total number of OV per category. We found that 69% (9 of the 13) of OV in the category developer were included in the 20 most relevant organizational values. Similarly, 45% (9 of the 20) of OV in the category top manager and 29% (9 of the 13) of OV in the category project leader were included into the 20 most relevant OV. Figure 2 shows this analysis.

Table 10: Analysis of OV’s Importance x Relevance Order

Figure 1: Distribution of the most important/relevant OV by category

This result indicates that although the developers and top manager have the same number of OV in the 20 most relevant OV (with 9 items each category), in proportion, the role of the development team would be more important for a software organization to obtain success in the implementation of an SPI initiative. This demonstrates that the developers must constantly contribute to the process and product quality control in a software organization to reach its goal.

Figure 2: Distribution of the twenty more relevant OV

4. Comparison with Related Works

In recent years, several studies have been conducted with the aim of identifying the motivations and difficulties that determine whether the adoption and implementation of an SPI initiative will be a success or a failure. On the whole, however, the focus of these studies has been more generalized, referring to these motivations and difficulties either as critical success factors (CSF) or risks factors (RF) in initiatives for improvement (2)(33)(34). Many of these factors concern organizational issues, which reinforces the premise that OC is an important aspect for the successful implementation of SPI initiatives.

Montoni and Rocha (33) investigated CSF that affect the implementation of SPI initiatives applying qualitative and quantitative methods of data analysis. Table 11 presents a comparison between the CSF from Montoni and Rocha (33) to the OV identified in our proposed systematic literature review.

As can be seen in Table 11, from the 25 critical factors identified by Montoni and Rocha (33), 18 are similar to OV found in the systematic review. This represents 72% of all critical factors. Twenty two OV were used for obtaining the similarities, and about 68% (15 of them) are among the 20 more relevant, according to our study, for a software organization involved in the implementation of an SPI initiative.

Niazi (34)also presentes a study reporting empirical study and literature survey of risk factors that impact SPI implementation. The objective of this exploratory research is to gain an in-depth understanding of risks that can compromise SPI implementation from the perspective of software development practitioners. Interviews were conducted as the main approach of data collection from 34 Australian SPI practitioners in 29 companies. The experiences, opinions and views of practitioners, identified via technical literature, were analysed too. Eighteen critical factors for the success of SPI initiatives were identified (see Table 12).

Table 11: Comparison with Montoni and Rocha’s work (33)

Analyzing the critical factors identified by Niazi (34), we can see that 14 of them, about 78%, were similar to the OV identified by this research, as shown in Table 12. In this case, 21 values were used for obtaining the similarities, and 67% (14 of them) are among the 20 more relevant according to order of relevance.

Table 12: Comparison with Niazi’s work (34)

Dyba (2)carried out an experimental investigation of key factors for the successful implementation of SPI initiatives based on the data collected from 120 software organizations. This is a seminal work in the area of software process improvement. In addition to this, Dyba (2) shows that for the successful running of SPI initiatives the organization needs to give special attention to organizational issues, as much as it gives to technological ones. Table 13 presents a comparison between the results of this experimental investigation with OV identified in the systematic review. We find similarities with seven critical success factors (see Table 13) and five values are among the ten most relevant.

Table 13: Comparison with Dyba’s work (2)

Table 14 presents a summary of the results found in the published studies of Dyba (2), Niazi 34), and Montoni and Rocha (33) respectively, comparing the occurrence of factors that can influence over SPI initiatives with the OV identified by this survey. We can observe that 83% of the critical factors described in Dyba’s (2) study, 72% of the critical factors described in Montoni and Rocha’s (33) , and 78% of risks factors described in the study of Niazi (34) are related to OV identified by this study.

Table 14: Summary of the results found in the comparison analyses

This reinforces the concept of the relevance of OC for the success of SPI initiatives because the similar OV that are the majority are also the most relevant, according to the critical factors identified in the studies cited above. Thus we provide evidence from the results of experimental studies that OC is an important aspect for the successful adoption and implementation of SPI initiatives.

5. Conclusion

Several software organizations are focused on improving the quality of their products and processes. One possible solution that may contribute to achieving these goals is to adopt SPI programs. But, often, this solution alone is not enough, since organizational issues are not addressed by these programs. Organizational culture consists of the specific identity of a company, which makes this company unique compared to others. This allows for having a vision of how the organization works internally (its goals, aims, decision-making, mission and standards), socially (interaction between the members, beliefs, attitudes, habits and behavior) and externally (customer relationship and business rules).

In addition, some OV are associated with OC, among them: competitiveness, commitment, collaboration, leadership and communication. These OV are very important for a company to achieve success and accomplish goals, and improve their products. Thus, those responsible for the implementation of SPI initiatives in software organizations must understand and appreciate the following OV: (1) optimize your results, (2) identify and promote behaviors to achieve your goals and (3) to improve the quality of your products.

For this reason, we conducted a systematic review aimed at identifying, analyzing and assessing typological models for OC analysis in order to extract the main OV from selected models.

Such typologies are considered as an alternative providing a simplified means for evaluating cultures and are therefore commonly used in studies on OC. Study by Cameron and Quinn (18), who identified the types i) clan ii) adhocracy iii) market and iv) hierarchical, contribute significantly to these typologies, as well as the study of Hofstede et al. (8).

We should also note that many publications address the topic of OC, but not specific typological models for analysis of OC. In this systematic review, we identified 36 models. From these, seven models were selected according to certain criteria that mainly consider the origin of the source, giving priority to books/papers of the author of the model. The model most often applied in the selected papers was that of Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn (18) being 42% of the total of all models, while the model most often cited was that of Hofstede et al. (8) being 20%.

After selection of the models 40 OV were extracted, which correspond to a set of attitudes and beliefs that guide company and employee behavior, and can serve as a guide to achieve success and survival in the job market.

The sources used for the search of the publications may be considered a limitation of this research. There are a variety of national and international journals, and conferences that were not consulted, because we had no access, despite being extremely important to the OC. There are also other models that were not examined because we did not have access to the paper/original book. However, these can be consulted later in order to extract more OV proposed by the OC.

From the systematic review, we executed a survey to verify, in the opinion of professionals in the industry and academia, which 40 OV are most important to characterize a software organization and which would be relevant for an organization implementing SPI initiatives.

The results indicated that for a software organization implementing SPI initiatives to achieve success, it must follow some recommendations:

-

The organization must be committed to the quality policy for products, services and processes;

-

The organization must provide salaries appropriate to a particular position;

-

The organization must have a clear and well-established vision, goals, and objectives;

-

The project leader must monitor planned activities;

-

The project leader must have and provide adequate information for decisions;

-

Team members must have a commitment to deadlines and goals;

-

Team members must be involved, committed, and participate.

It becomes also clear that the OC needs to be aligned with the organization’s actions and proceedings, such as planning, investments, communication and management, since the CSF for SPI initiatives identified in other studies are generally related to OC.

Our findings support the idea that the developers need to act in conjunction with the managers when implementing an SPI initiative. They need to take part in the planning process and monitor the actions required by the adopted program in order to guarantee that the product delivered is in fact what the client expected, a quality product delivered within the agreed time frame. As further work, a study can be carried out in such a way that experimented SPI practitioners might indicate the most appropriated professional for implementing the organizational value in software organizations.

We intend to suggest recommendations on how OV can contribute to an SPI initiative’s success in the software development context (35). Thus, we are developing a framework to support SPI initiative according to OV. Specifically, we want to propose a mechanism to reduce the impact of such an implementation in a software organization thus contributing to the success of this initiative.

In conclusion, it can be observed that software organizations need to understand the importance of OC as a factor for achieving the established goals and targets and motivating the collaborators involved in the process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Foundation of Support the Research of the State of Amazonas (FAPEAM), Brazil. Jim Hesson of AcademicEnglishSolutions.com proofread the English.

REFERENCES

(1) C. Shih and S. Huang, “Exploring the Relationship Between Organizational Culture and Software Process Improvement Deployment”, Information and Management, vol. 47, pp. 271-281, 2010.

(2) T. Dyba, “An Instrument for Measuring the Key Factors of Success in Software Process Improvement”, Empirical Software Engineering, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 357-390, 2000.

(3) S. Muller, P. Kræmmergaard, and L. Mathiassen, “Managing Cultural Variation in Software Process Improvement: A Comparison of Methods for Subculture Assessment”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 584-599, 2009.

(4) S. Muller, A. Nielsen, and M. Boldsen, “An Examination of Culture Profiles in a Software Organization Implementing SPI”, in: 16th European Conference on Information Systems, Galway, 2008.

(5) S. Muller, L. Mathiassen, and H. Balshoj, “Software Process Improvement as Organizational Change: A Metaphorical Analysis of the Literature”, The Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 83, no. 11, pp. 2128-2146, 2010.

(6) G. Hofstede, Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

(7) S. Robbins, Organizational Behavior, 11th ed., New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Pearson Education, 2005.

(8) G. Hofstede et al., “Measuring Organizational Cultures: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study Across Twenty Cases”, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 286-316, 1990.

(9) C. Enz, “The Role of Value Congruity in Intraorganizational Power”, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 33, pp. 284-304, 1988.

(10) P. Webster, Why are Expectations of Grievance Resolution Systems not Met? A Multi-Level Exploration of Three Case Studies in Australia. Custom Book Centre, University of Melbourne, 2010.

(11) E. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd ed., San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2004.

(12) S. Michailova and D. Minbaeva, “Organizational Values and Knowledge Sharing in Multinational Corporations: The Danisco Case”, International Business Review, vol. 21, pp. 59-70, 2012.

(13) A. Dias-Neto, R. Spinola, and G. Travassos, “Developing Software Technologies Through Experimentation: Experiences from the Battlefield”, in XIII Ibero-American Conference on Software Engineering, Cuenca, 2010.

(14) B. Kitchenham, “Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews”, Software Engineering Group, Department of Computer Science, Keele University, Joint Technical Report TR/SE 0401, 2004.

(15) J. Biolchini et al., “Systematic Review in Software Engineering”, Systems Engineering and Computer Science Department, COPPE/UFRJ, Technical Report TR/ES 679/05, 2005.

(16) B. Kitchenham and S. Charters, “Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering”, Software Engineering Group, Evidence-Based Software Engineering (EBSE), Technical Report TR/EBSE 2007-01, 2007.

(17) K. Petersen et al., “Systematic Mapping Studies in Software Engineering”, in Proceedings of the Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (EASE'08), pp. 1-10, Bari, Italy, 2008.

(18) K. Cameron and R. Quinn, Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on The Competing Values Framework, The Jossey-Bass Business & Management Series, 2006.

(19) D. Denison and A. Mishra, “Toward a Theory of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness”, Organizational Science, vol. 6, no. 2, 1995.

(20) D. Denison, Organizational Culture: Can It Be a Key Lever for Driving Organizational Change?, in Cartwright, S., Cooper, C., The Handbook of Organizational Culture. John Wiley and Sons, London, UK, 2000.

(21) G. Hofstede, Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, Unit 2, 2009. Available: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/orpc/vol2/iss1/8.

(22) M. Niazi, D. Wilson, and D. Zowghi, “A Maturity Model for the Implementation of Software Process Improvement: An Empirical Study”, Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 155-172, 2005.

(23) C. Handy, Understanding Organizations, 4th ed., Penguin, 1993.

(24) R. Daft, Organization Theory and Design, 10th ed., South-western College Pub, 2009.

(25) R. Nelson, Organizational Culture: Winning the Dragon of Resistance, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Imagem, 1996 (in Portuguese).

(26) W. Schneider, The Reengineering Alternative: A Plan for Making your Current Culture Works, 1st ed., Mcgraw-Hill Companies, 2000.

(27) V. Basili, G. Caldiera, and H. Rombach, The Experience Factory, J. Marciniak (Ed), in Encyclopedia of Software Engineering, New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1994.

(28) Association for the Promotion of Brazilian Software Excellence (SOFTEX), “MPS.Br – Software Process Improvement in Brazilian – Gereral Guide”, 2012. Available: http://www.softex.br/mpsbr (in Portuguese).

(29) A. Dias-Neto and G. Travassos, “Surveying Model Based Testing Approaches Characterization Attributes”, in International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM), Kaiserslautern, 2008.

(30) M. Hamburg, “Basic Statistics: A Modern Approach”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (General), vol. 143, no. 1, 1980.

(31) A. Rocha et al., “Success Factors and Difficulties in Software Process Deployment Experiences based on CMMI and MR-MPS.BR”, in 6th International Workshop on Learning Software Organizations (LSO'2006), pp. 77-87, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2006.

(32) Software Engineering Institute (SEI), “CMMI for Development (CMMI-DEV)”, version 1.3, CMU/SEI-2010-TR-033, 2010. Available: http://www.sei.cmu.edu/reports/10tr033.pdf.

(33) M. Montoni and A. Rocha, “Applying Grounded Theory to Understand Software Process Improvement Implementation” in 7th International Conference on the Quality of Information and Communications Technology, Portugal, pp. 25-34, 2010.

(34) M. Niazi, “An Exploratory Study of Software Process Improvement Implementation Risks”, Journal of Software Maintenance and Evolution: Research and Practice, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 877-894, 2012.

(35) O. Passos, A. Dias-Neto, and R. Barreto, “Organizational Culture and Success in SPI Initiatives”, IEEE Software, vol. 29, pp. 97-99, 2012.