1. Introduction

Soil microbiota (bacteria, archaea, fungi, protists, and viruses) associated with vineyards are essential for agroecosystem health and productivity1. Bulk soil microbiota is a major reservoir of microorganisms for the rhizosphere2 and aerial organs as leaves, flowers and grapes3. It is widely recognized that the sensory qualities of a wine from a specific region are defined by abiotic (climate, soil) and biotic (grape variety and rootstock and soil biology) factors along with anthropogenic ones (viticultural management and winemaking techniques), defining the concept of terroir4. In addition to these influences, recent studies emphasize the role of native vine microbiota in the winemaking process, imparting a unique character to the wines of each region5. As well, the potential influence of soil microbiota on grape and wine quality has also been suggested 4)(6) . With the advances and increasing accessibility of high-throughput sequencing technology, more information is available worldwide about the microbial communities associated with vineyard soils and the key factors that drive their diversity and structure. Spatial distance or geographic location 7)(8) 9, climate8, and agricultural management 10)(11) 12 are factors that have a determinant role in vineyard soil microbiota.

With regard to agricultural management, previous studies have shown that the use of cover crops and different soil management strategies under vines in vineyards influenced the composition and diversity of soil microbial communities. For example, Chou and others10 found that soil management under vines in vineyards altered the composition of soil microbial communities, although the microbiome of grapefruit was not affected. Similarly, Hendgen and others11 showed that different management regimes (integrated, organic, and biodynamic) shaped the composition of fungal community in vineyard soils, and that vegetation under vines increased the richness and activity of soil-borne fungi. In contrast, bacterial communities were more uniform across all treatments, although richness was reduced under integrated management. Longa and others12 also observed that green manure was the greatest source of soil microbial biodiversity and significantly changed microbial richness and community composition compared with other soils. Taken together, these studies support the idea that under-vine vegetation and cover crop strategies can modulate the microbial community dynamics in vineyard soils. Under-vine cover crops or living mulches in sustainable agricultural management are a promising strategy for simultaneously enhancing many ecosystem processes13. The use of cover crops or living mulches in vineyards serves multiples purposes, among them: 1) reducing plant vigour in regions with excessive precipitation, 2) diminishing cluster rot development through modifications in canopy microclimate, 3) minimizing herbicide use, and 4) fostering improvements in soil organic carbon (SOC), aggregate stability, soil respiration, and microbial diversity14. Despite these well-documented benefits, Uruguayan winegrowers primarily rely on herbicide application to maintain bare soil under the vine, particularly within non-irrigated vineyards15.

The rhizosphere microbiota is the result of complex interactions in which both plant and soil characteristics play a key role in shaping its structure, stability, and succession16. Previous studies conducted in a Tannat/SO4 vineyard in Uruguay showed that under-vine soil management can influence both the sensory attributes of wine17 and the composition of prokaryotic and fungal communities in the grapevine rhizosphere18. In particular, the use of an under-vine cover crop was associated with improved soil and vine health 17)(18) , and promoted the recruitment of microbial taxa with known beneficial traits18. However, the study by Bernaschina and others18 focused on a single vineyard and specifically on the rhizosphere compartment. In contrast, little is known about the diversity and composition of bulk soil microbiota -the broader reservoir from which rhizosphere communities are assembled- in Uruguayan soils, particularly those associated with vineyards.

To address this gap, the present study investigates whether there are significant differences in the composition of soil prokaryotic and fungal communities across three Tannat vineyards managed with herbicides under the vines (conventional soil management), and evaluates, within each site, the effect of permanent living mulch (PLM) as an alternative management strategy. Amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and ITS2 region was used to analyze bulk soil microbial diversity, as well as the shared and differentially abundant taxa among vineyards and under-vine soil management practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Site Characteristics

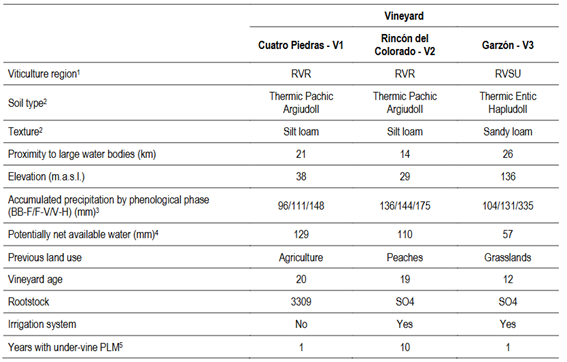

The study was conducted in Southern Uruguay, which accounts for 92% of the vineyards area in the country19. The three vineyards of Tannat cultivar were located in Cuatro Piedras-V1 (34º 62' S, 56º 28' W), Rincón del Colorado-V2 (34°44′ S, 56°13′ W) and Garzón-V3 (34.57' S, 54.63 W), geographically separated as follows: V1-V2 9 km, V1-V3 152 km and V2-V3 158 km (Figure S1, in Supplementary material). The vineyards exhibit differences in soil type, land use history and plant age (Table 1). According to the viticultural zoning of Uruguay based on bioclimatic indices (Heliothermal, Dryness, and Cool Night)20, the three vineyards belong to the same climatic type IHA3 IFA2 ISA1, all of them influenced by the Atlantic Ocean and the estuary of Río de la Plata. The climatic type IHA3 IFA2 stands for temperate climate, moderate drought from bud break to harvest, and mild nights (14-18 °C) from veraison to harvest.

Table 1: Characterization of the three Uruguayan vineyards studied

Note: 1 Uruguayan viticulture region (RVR: Rioplatense, RVSU: Sierras del Uruguay). 2 According to USDA Soil Taxonomy56. 3 BB-F (from bud breaking to flowering), F-V (from flowering to veraison), V-H (from veraison to harvest). 4 V1 and V3 according to Molfino21. V2 estimated by Coniberti and others17. 5 PLM: permanent living mulch.

Vines were trained to a vertical shoot positioning system with a planting density of approximately 1 m within rows and 2.5, 2.8 and 2 m between rows in V1, V2 and V3, respectively. Vineyard V1 was not irrigated, while in V2 and V3, the irrigation strategy aimed to avoid severe water stress until berries pea-sized stage (stage 3122). From then on, deficit irrigation (70% ETc) was applied for all treatments once the plants reached -0.7 MPa mid-day stem water potential (Ψstem). To prevent Ψstem from becoming more negative than -1.1 MPa after a prolonged period of deficit irrigation, the amount of water the vines had consumed the previous week was occasionally applied at 100% ETc.

2.2 Under-Vine Soil Management

The three vineyards implemented two under-vine soil managements (U-VSM): bare soil by herbicide use (BS) and permanent living mulch (PLM). The treatments were imposed in alternating rows in each vineyard. Within each row with homogeneous management (BS or PLM), four plots with eight consecutive plants with similar plant vigour were defined. In vineyards V1 and V3, PLM and BS were implemented in March 2020, while in V2 in 2011.

The BS management consists of a 1.0 m-wide weed-free strip under the vine with a combination of herbicides: 3 applications of glyphosate (1L/ha) and one application of glufosinate-ammonium (3 L/ha) during grapevine growing season. Herbicide sprays were separated by at least one and a half months before the soil sampling date. PLM in vineyards V1 and V3 consisted of spontaneous vegetation characterized mainly by a mixture of gramineous species, while in V2 it corresponds to a Festuca arundinacea (Schreb.) crop (“tall fescue”) established in 2011 with a seeding rate of 60 kg/ha. In all cases, the alleys between the rows consisted of permanent spontaneous vegetation mowed when necessary.

2.3 Soil Sampling

Soil samples were collected at harvest in March 2021 (phenological stage 3822). Eight composite bulk soil samples were collected per vineyard, four from PLM plots and four from BS plots, totaling 24 samples. Each composite sample consisted of 20 soil cores randomly collected with a soil core auger (2 cm diameter) at 0-15 cm depth, mixed and homogenized by sieving with a 2 mm mesh (roots and stones previously removed by hand) immediately after sampling. Then, the soil sample was split into subsamples for the different analyses.

2.4 Soil Biological and Physicochemical Property Analyses

Soil basal respiration (SR), autoclaved citrate-extractable soil protein (SP), and potentially oxidizable carbon (PoxC) were assessed in bulk soil samples (0-15 cm depth)23. SR and SP were determined in air-dried soil, while PoxC was measured in fresh soil stored at 4 °C until analysis. SR, used as a proxy for microbial activity, was measured by incubating 20 g of sieved soil for 4 days at 21 °C in sealed jars containing a 0.5 M KOH CO₂ trap, with CO₂ release estimated based on conductivity changes. SP, reflecting labile organic nitrogen, was extracted from 3 g of soil using sodium citrate buffer, autoclaved, and quantified via the BCA assay. PoxC, representing readily available organic carbon, was determined by oxidation with 0.2 M KMnO₄, and absorbance was measured at 550 nm to estimate carbon content. Air-dried bulk soil samples were analyzed at the Laboratorio de Suelos y Plantas - INIA La Estanzuela (http://www.inia.uy/productos-y-servicios/laboratorios/Laboratorio-de-Suelos-Plantas-y-Agua) for electrical conductivity (EC, mmhos/cm 25 ºC), pH (H2O), Total N (%), soil organic carbon - SOC (%), P Bray 1 (µg P/g), Ca (meq/100g), Mg (meq/100g), K (meq/100g), and Na (meq/100g). Soil bulk density (SBD) (2-7 cm depth) was determined by weighing the dry soil contained in a metal ring of known volume24.

Soil under-vine management effects on soil physicochemical and biological properties were analyzed using linear models. In the case of the significance for Fisher test (Type III ANOVA), mean separation was performed by computing the estimated marginal means. Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.0.4, with the package’s stats, lme425, lmerTest26, performance27, emmeans28, multcomp and multcompView29.

2.5 Soil Microbial Community Analysis

Total community-DNA (TC-DNA) was extracted from 500 mg of frozen bulk soil (wet weight) stored at −20°C with the Fast DNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA), using a Fast Prep-24-bead-beating system, following the manufacturer's instructions. The integrity and concentration of TC-DNA were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Invitrogen, USA), respectively.

From 24 bulk soil samples, the microbiota was determined by amplicon sequencing using Illumina MiSeq (2 × 300 bp, paired/end) at Macrogen Inc. (Korea). For the prokaryotic communities, the 16S rRNA gene (V3-V4 region) was selected and amplified with primers 341F 5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3' and 805R 5'-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3'30. For the fungal communities, the ITS2 region was selected and amplified with primers 3F: 5'-GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC-3' and 4R: 5'-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3'31.

Raw sequence reads quality was evaluated using FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and the subsequent analyses were performed in R v4.0.4 environment. The DADA2 v1.24.0 package32 was used to filter and trim the reads, correct by error learning, merge pairs and identify amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Prokaryotic reads (16S) were trimmed after 250 bp while fungal (ITS2) reads were trimmed after 280 bp and 250 bp for forward and reverse, respectively. Also, 16S and ITS2 reads with expected errors higher than 3 for forward and reverse reads were discarded. The remaining filters were used by default. Reads were merged with a minimum overlap of 20 bp and a maxMismatch of 0. Chimeric sequences were identified and removed. For the quality control, we focused on filtering rare ASVs based on prevalence. First, we calculated the prevalence of each ASV across samples, added taxonomic information, and identified low-represented phyla that could be false positives, which were subsequently removed. Non-microbial taxa, such as chloroplasts and mitochondria, were also excluded. Taxa with a mean read count below a set threshold (1e-5) or observed in fewer than 10% of samples were filtered out. Samples with fewer than 1000 reads were also discarded, although no samples were removed in this case. Finally, a prevalence threshold of 5% was applied, keeping only ASVs present in at least 5% of the samples. ASVs taxonomic assignment was realized against reference training dataset SILVA v138.1 database33 for prokaryotes and UNITE reference database (sh_general_release_dynamic_s_10.05.2021) for fungi34. Classification and subsequent analyses were done with Phyloseq v1.34.035.

Alpha diversity indexes (Shannon, Pielou's evenness, Species Richness) were estimated using Microbiome v1.12.036. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Permanova) based on Bray-Curtis’s distance was run with 10,000 permutations using Vegan v2.5.737 to test the effect of the vineyards with conventional management and the effect of U-VSM within each vineyard on the prokaryotic and fungal communities. Within the same package, a pairwise multilevel comparison using adonis2 was performed to test for differences among vineyards, and the analysis of multivariate homogeneity of group dispersions (variances) was done using betadisper. A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-curtis dissimilarity as the distance method was performed to illustrate differences between the community's composition for prokaryotic and fungi separately. All data visualizations were produced using the ggplot2 package v3.4.438.

To determine the core community across different vineyards for prokaryotes and fungi, the amp_venn function from the ampvis2 package was employed39. The analysis was grouped by the factor “vineyard” to investigate shared and unique prokaryotic and fungal taxa among vineyards. A minimum relative abundance threshold (cut_a) of 0.01% was set to ensure that only amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) present above this threshold were considered in the analysis. Additionally, a frequency cutoff (cut_f) of 50% was applied, meaning that an ASV must be present in at least 80% of the samples within each vineyard group to be included in the core microbiota.

Differential abundance (DA) analysis was performed using the analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOM-BC2) among vineyards and between U-VSM within V2 from package ANCOM-BC40.

2.6 Accession Numbers

Unassembled raw amplicon data were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and can be retrieved under BioProject accession number PRJNA1032922.

3. Results

3.1 Diversity and Composition of Vineyard Microbiota Managed with Under-Vine Herbicide

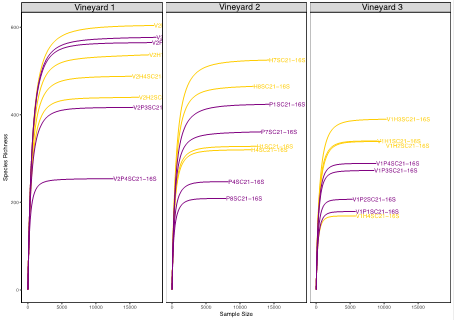

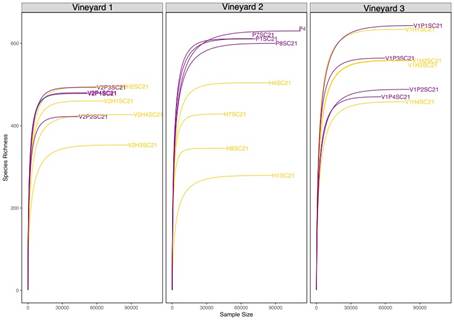

A total of 1,487,685 and 1,547,636 reads were processed for the 16S and ITS2 datasets, respectively. Following quality filtering, 6,722 prokaryotic ASVs and 3,661 fungal ASVs were identified. The sequencing depth was enough to cover the microbial diversity, as a plateau was reached in the rarefaction curves (Figure S2 and Figure S3, in Supplementary material).

The relative abundance profiling of prokaryotic communities was similar among vineyards, with Actinobacteriota and Proteobacteria as the most abundant phyla (Figure S4 A, in Supplementary material). The relative abundance profile of prokaryotic and fungal communities was similar among vineyards. The phyla Actinobacteriota and Proteobacteria were the most abundant prokaryotes (Figure S4 A, in Supplementary material), and Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota and Mortierellomycota were the most abundant fungal phyla (Figure S4 B, in Supplementary material).

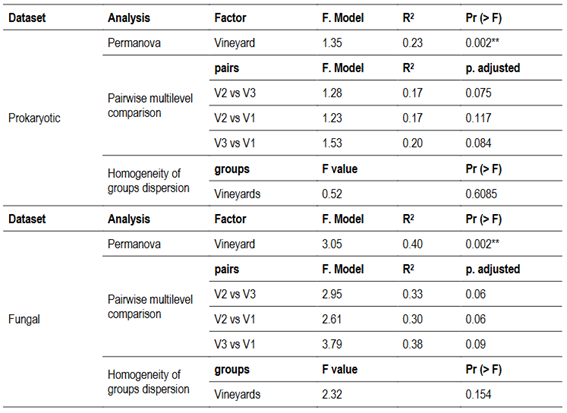

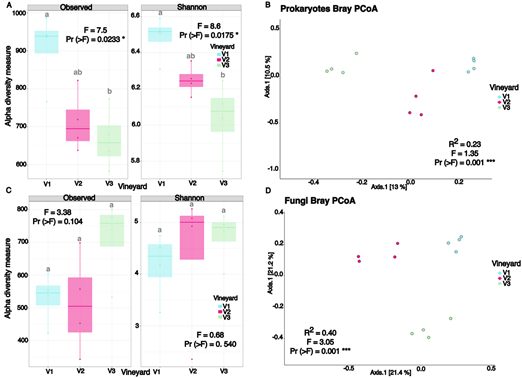

Alpha diversity indices (Observed ASVs and Shannon) revealed statistically significant differences among vineyards, but only for prokaryotic communities (Figure 1 A and C). Vineyard V1 exhibited higher Observed ASVs and Shannon diversity values compared to V3, while V2 did not differ significantly from either V1 or V3. Vineyard identity accounted for 23% and 40% of the variation in beta diversity for prokaryotic (R² = 0.23, p = 0.001) and fungal communities (R² = 0.40, p = 0.001), respectively. However, no significant differences were found between the three vineyards for either prokaryotic or fungal communities in the multilevel pairwise comparisons (Table 2, Pr (>F) > 0.05). Variances for both prokaryotic and fungal communities were homogenous (Pr (>F) for prokaryotes = 0.609; Pr (>F) for fungi = 0.154). PCoA visualizations showed that, for both communities, V1 and V2 clustered together and separated from V3 (Figure 1 B and D).

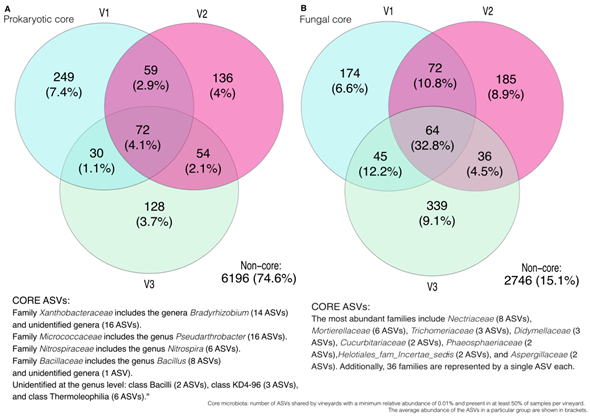

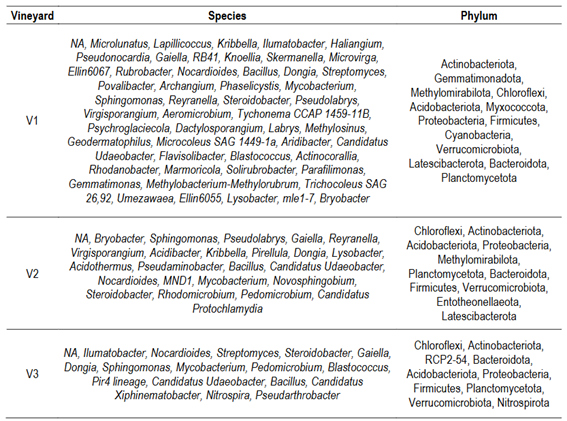

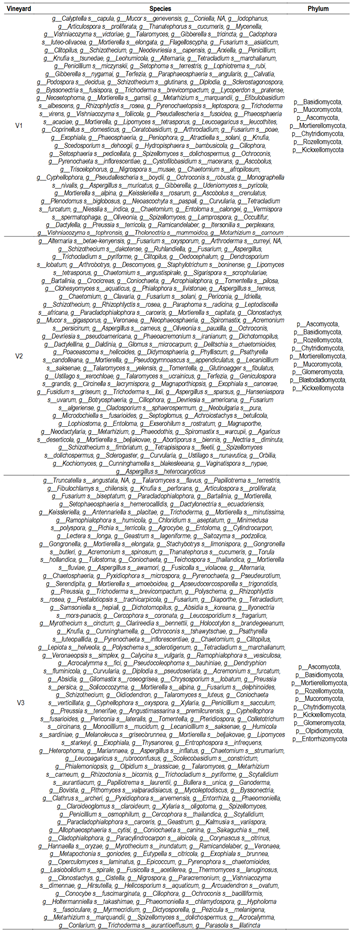

The core microbiota -shared taxa- among vineyard soils was composed of 72 prokaryotic and 64 fungal ASVs (Figure S5 A and B, in Supplementary material). The most represented taxa for prokaryotes were Xanthobacteraceae family (30 ASVs), from which the genus Bradyrhizobium accounted for 14 ASVs, while 16 ASVs could not be identified at genus level. The most represented families in the fungal core include Nectriaceae (8 ASVs), Mortierellaceae (6 ASVs), Trichomeriaceae (3 ASVs), Didymellaceae (3 ASVs), Cucurbitariaceae (2 ASVs), Phaeosphaeriaceae (2 ASVs), Helotiales_fam_Incertae_sedis (2 ASVs), and Aspergillaceae (2 ASVs). Additionally, 36 families were represented by a single ASV each. Several prokaryotic unique ASVs were identified for each vineyard (Figure S5 and Table S1, in Supplementary material). The most represented phylum for V1 were Actinobacteriota (132 ASVs), followed by Proteobacteria (39 ASVs) and Acidobacteriota (23 ASVs); for V2, Verrucomicrobiota (41 ASVs), followed by Actinobacteriota (36 ASVs), Proteobacteria (26 ASVs) and Firmicutes (11 ASVs); and for V3, Proteobacteria (40 ASVs), Actinobacteriota (30 ASVs) and Firmicutes (22 ASVs). Regarding unique fungal ASVs (Figure S5 and Table S2, in Supplementary material), the most represented phylum for V1 were: Ascomycota (113 ASVs), followed by Basidiomycota (35 ASVs), Chytridiomycota (11 ASVs) and Mortierellomycota (10 ASV); for V2, Ascomycota (132 ASVs), Basidiomycota (22 ASVs); and for V3, Ascomycota (223 ASVs), Basidiomycota (53 ASVs), Chytridiomycota (15 ASVs), Mortierellomycota (14 ASVs) and Rozellomycota (13 ASVs).

Table 2: Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Permanova), pairwise multilevel comparison among vineyards and multivariate analysis of homogeneity of groups dispersion based on Bray-Curtis distance for prokaryotic and fungal communities

Vineyards: V1 (Cuatro Piedras), V2 (Rincón del Colorado) and V3 (Garzón), Uruguay

Figure 1: Alpha diversity indexes (Observed ASVs, Shannon) and Principal Coordinates Analysis based on Bray-Curtis distance of prokaryotic (A-B) and fungal communities (C-D), respectively

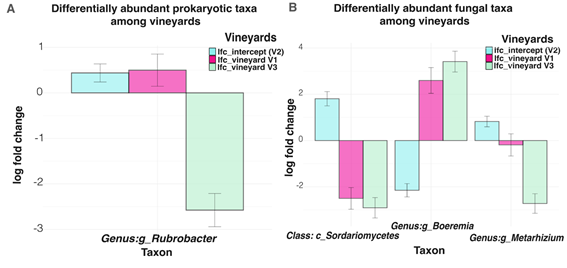

A few differentially abundant taxa, named responders, were detected for prokaryotic and fungal communities. Rubrobacter was the only prokaryotic genus identified as differentially abundant among vineyards for prokaryotic communities (Figure 2 A). The vineyard V3 had a lower abundance of Rubrobacter in comparison to V2 (q-value = 0.01), whilst among V1 and V2 no differences were found.

For fungal communities, 2 genera and 1 class were identified as differentially abundant between vineyards V3 and V1 and V2 (Figure 2 B). The vineyard V3 showed a higher abundance of genus Boeremia (q-value = 0.01) and a lower abundance of class Sordariomycetes (q-value = 0.02) and the genus Metarhizium (q-value = 0.03) in comparison to V2 (intercept).

3.2 Impact of Under-Vine Soil Management on Soil Microbiota and Properties in Vineyards

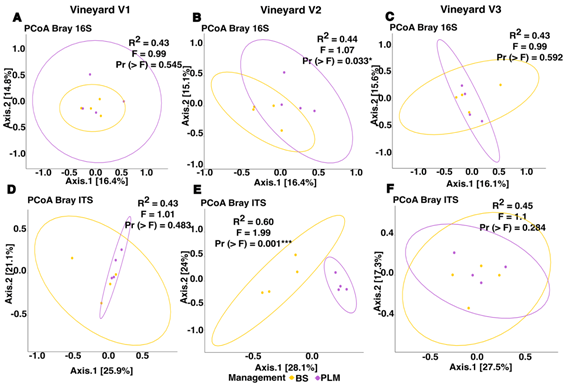

Analyses of the composition analyses of prokaryotic and fungal communities within vineyards revealed a significant impact of U-VSM solely in V2, the vineyard with a 10-year implementation of PLM (Figure 3). Permanova demonstrated a significant effect of U-VSM on both prokaryotic (F = 1.23, R² = 0.15, Pr (>F) = 0.006***) and fungal communities (F = 2.7, R² = 0.27, Pr (>F) = 0.001***). The homogeneity of dispersion tests ensured comparable variances within the prokaryotic (F = 0.7, Pr (>F) = 0.444) and fungal communities (F = 3.5, Pr (>F) = 0.112) across different U-VSM. PCoA visualization further supported these findings with more pronounced separation for fungal communities (Figure 3 B and E).

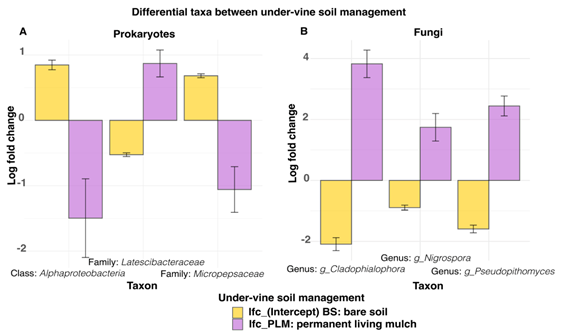

In V2, three taxa were identified as key responders to soil management practices, for both prokaryotes and fungi. Among the prokaryotic responders, the class Alphaproteobacteria and the family Micropepsaceae were more abundant in BS, whereas the family Latescibacteraceae was prevalent in PLM. For fungi, the genera Cladophialophora, Nigrospora, and Pseudopithomyces were more abundant in PLM (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Principal Coordinates Analysis based on Bray-Curtis distance of prokaryotic (A-C) and fungal communities (D-F) from vineyard soils with two under-vine soil management: Bare soil (BS) and PLM (permanent living mulch)

Figure 4: Differentially abundant taxa between under-vine soil management (Bare soil-BS and Permanent living mulch-PLM) in vineyard V2 for prokaryotic (A) and fungal (B) communities

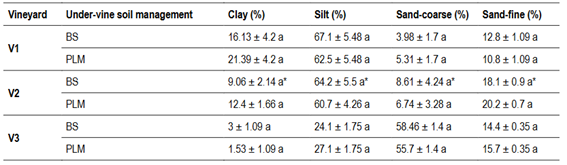

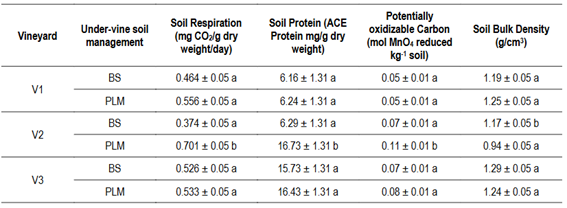

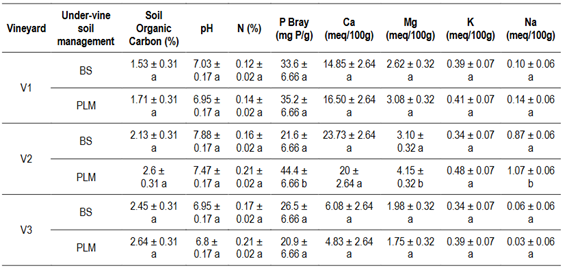

Regarding soil properties, soil respiration (SR), soil protein (SP), potentially oxidizable Carbon (PoxC) and soil bulk density (SBD) were significantly different only for U-VSM in V2. Mean values for SR, SP, PoxC were 47%, 63% and 36% higher and SBD 20% lower in PLM than in BS (Table 3). P Bray, Mg, and Na content were also affected by U-VSM, showing higher values under PLM in comparison to BS (Table 4), while texture variables were not affected (Table S3, in Supplementary material).

Table 3: Soil biological and physical properties from vineyard soils with two under-vine soil management: bare soil (BS) and permanent living mulch (PLM)

Lower case letters in the columns indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA, p < 0.05) between under-vine soil management within vineyards. V1 (Cuatro Piedras), V2 (Rincón del Colorado) and V3 (Garzón), Uruguay.

Table 4: Soil chemical properties from vineyard soils with two under-vine soil management: bare soil (BS) and permanent living mulch (PLM)

Lower case letters in the columns indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA, p < 0.05) between under-vine soil management within vineyards. V1 (Cuatro Piedras), V2 (Rincón del Colorado) and V3 (Garzón), Uruguay.

4. Discussion

4.1 Soil Microbial Community Composition Shows Moderate Differences among Tannat Vineyards under Conventional Herbicide Management

This work provides information on the impact of vineyard under-vine soil management on bulk soil microbiota. The composition of the bulk soil prokaryotic and fungal communities did not exhibit significant differences between the studied vineyards, despite notable variations in cropping history, irrigation practices, altitude and soil types (V3 vs V1 and V2). Although pairwise Permanova comparisons between vineyards did not remain significant after FDR correction, the global analysis indicated a significant effect of vineyard for both prokaryotic and fungal communities. Furthermore, the Bray-Curtis PCoA visualization suggests that V3 is distinct from V1, and especially from V2, which could reflect the differences mentioned above. These observations highlight that, even with similar herbicide management under the vines, site-specific factors may contribute to shaping the composition of the microbial community. Although our study was conducted in a limited geographical area with vineyards sharing the same climatic classification (IHAS IFA2 ISA1)20, previous research indicated that biogeographical soil patterns exert a strong influence on microbial diversity, which can vary between regions and between vineyards 4)(41) . The same land-use (Tannat vines) and uniform soil management (bare soil with herbicides) over at least ten years is likely to have resulted in the homogenization of soil microbial communities. This phenomenon has been observed at global and regional scales, where monoculture-dominated landscapes reduce environmental heterogeneity, leading to homogenization of soil microbiome composition42. The differential abundance analysis confirms these findings, with only a few taxa being differentially abundant among vineyards. Despite some differences were observed, such as lower relative abundance of Rubrobacter in V3 and higher abundance of Sordariomycetes and Metarhizium in V1, the ecological relevance of these taxa remains uncertain. These groups are commonly found in soil, and their differential abundance may reflect multiple factors beyond soil composition alone, such as microclimatic conditions or historical land use. While V3 differs in certain soil properties (e.g. texture) compared to V1 and V2, no direct correlation analysis was performed. Therefore, further research would be needed to clarify whether these taxa respond consistently to soil characteristics or hold functional importance in vineyard ecosystems.

Beta diversity revealed only subtle differences among vineyards; a small core of prokaryotic taxa was found, while fungal communities exhibited a larger core microbiota in terms of mean relative abundance. The relatively small core suggests a high microbial diversity among less abundant taxa, which may be attributed to substantial intra-vineyard variability. The intra-vineyard variability of soil properties has been observed in other Uruguayan vineyards within the same viticultural region as V1 and V2 (viticulture region: RVR). Particularly those variables related to soil moisture (e.g. electrical conductivity and clay content), nutrient availability (e.g. pH, calcium, magnesium, and potassium), and root development (e.g. sand content, sodium, and soil penetration resistance) have been identified as playing a critical role in the spatial differentiation of zones within a vineyard43.

In the present study, bulk soil microbiota or some differentially abundant taxa may not yet be considered a reliable indicator to differentiate among vineyards. Nevertheless, further research involving a higher number of vineyards may reveal more profound distinctions and contribute to the definition of viticultural zones including information about microbial patterns. The potential of using microbiome data to differentiate vineyards has recently been the subject of considerable interest, given the pivotal role played by the microbiota in shaping the terroir and influencing grape and wine quality 3)(4) .

4.2 Lasting Permanent Living Mulch Shaped the Soil Microbial Composition within the Vineyard

The most substantial effect of U-VSM on bulk soil microbiota and properties was observed in vineyard V2, where PLM has been implemented for at least ten years. No differences in community composition and soil properties were observed between soil managements in either V1 or V3 vineyards, which had undergone a single year of implementation of PLM management. Our results suggest that soil microbiota and soil physical, chemical and biological properties need time to evolve in order to detect differences between managements.

The use of permanent living mulches or cover crops in vineyard soils (under the vine and between rows) is an alternative to the conventional management of spraying herbicides to avoid competition for water and nutrition15. Permanent living mulches provide several benefits, such as weed suppression, carbon sequestration, avoiding erosion and nutrient leaching and soil health promotion14. Little is known about how soil microbiota is impacted by PLM in vineyards and how many years are needed to observe significant changes, besides these changes may be different for prokaryotic and fungal communities. Soil microbiome is intricately linked with soil structure44. A stronger effect of geography has been suggested for bacterial community composition, while fungi seem more responsive to soil management or land use45, especially when implementing tillage practices, probably due to the mechanical disruption of hyphal networks46. But also soil coverage strongly influences soil temperature and water dynamics47, and soil porosity and pore connectivity determine water availability and oxygen flux, modulating soil microbiota 46)(48) . Furthermore, cover crops can influence microbial communities through diverse carbon inputs49, which microorganisms then degrade or employ as substrate for production of soil-binding agents44. In our study, soil health indicators like SR, PoxC, SP and SBD suggested these potential impacts on soil microbiota.

PLM showed a major abundance of family Latescibacteraceae, while BS was characterized by a major abundance of Alphaproteobacteria and the family Micropepsaceae. In a previous study carried out in the same vineyard (V2) at three different phenological stages, U-VSM also affected grapevine rhizosphere microbiota, with several Alphaproteobacteria also identified as responders to herbicide use18. The prevalence of Alphaproteobacteria in soils managed with herbicides can be attributed to a multitude of ecological and environmental variables. The application of herbicides has the potential to disrupt plant-microbe interactions, reducing the availability of plant-derived carbon sources50 and creating an environment conducive to the proliferation of microorganisms adapted to survive in low-nutrient environments51, like Alphaproteobacteria. This class is renowned for a multitude of members with a pivotal role in nitrogen cycling52, which can be vital in soils where plant derived inputs, like root exudates or plant debris, are minimal.

The increased abundance of Cladophialophora, Nigrospora, and Pseudopithomyces in soil with PLM can be attributed to several factors. Vines managed with PLM, as opposed to bare soil, support more complex ecosystem-level interactions where soil microbiota are influenced not only by root exudates from the vines but also by the plant species that integrate the PLM53. In our study, root exudates from tall fescue, a perennial grass, provide a continuous and additional source of carbon and nutrients, promoting microbial growth and creating favorable conditions for saprophytic fungi 53)(54) . In addition to root exudates, the presence of plant residues offers a substrate for fungal species involved in decomposition processes55. Moreover, the enhanced soil structure (estimated by SBD) resulting from PLM is likely to provide a more conducive environment for fungal growth than the more compact and nutrient-poor conditions observed in bare soil.

Given the variability of factors that influence the composition of soil microbiota, it is crucial to determine whether the differentially abundant group for each management is consistent at different times (years of implementation, seasons, phenological stages) and soil/rhizosphere and plant compartments (roots, leaves, flowers and grapes) for the same vineyard and between vineyards with similar history of soil management implementation. Once the genera or groups that are consistently promoted by a particular management have been identified, further studies about their functional significance can be undertaken. By understanding the unique or differentially abundant microbial taxa associated with specific soils and managements, we may gain insights into how the soil microbiome contributes to the terroir concept, potentially impacting grape and wine quality, enriching our understanding of terroir beyond traditional climatic and geographic parameters.

5. Conclusions

Despite differences in crop history, irrigation practices, and soil types, continued herbicides use and bare soil maintenance might have contributed to reducing variability in bulk soil microbiota composition across vineyards. Vineyards with more than ten years of PLM exhibited distinct microbial communities and improved soil properties compared to BS, reinforcing the role of sustained management in shaping soil microbiota. Our findings emphasize the need for long-term studies to capture microbial responses to soil management practices. Additional research incorporating a wider range of vineyards could refine microbial-based indicators for viticultural zoning, providing valuable insights into the microbial dimension of terroir and its implications for sustainable vineyard management.