1. Introduction

The agri-food sector plays an important role in providing food and fiber for a growing population and supplying a wide variety of inputs for the industry. Currently, the way in which we produce, distribute, sell and consume agri-food products is affected by crises in several dimensions, interconnected and unprecedented1. This context hinders necessary transformations towards sustainability; reduction of hunger, poverty and inequalities; digital inclusion of part of the world population, and advancement in regulatory aspects, business models and governance to support this process. Some of these challenges are 2)(3) : to provide food in a way that guarantees livelihoods for everyone working in the food supply chain, and contribute to environmental sustainability, considering the growing scarcity of natural resources, such as water and land, and global climate change caused by human action.

Some events further increase the uncertainties associated with global agriculture, such as the effects of a recent pandemic of the new Coronavirus (Sars-CoV-2)4 and armed conflicts -between Russia and Ukraine, which began in 2022, and between Israel and Hamas, in Palestine, started in 2023-. Conflicts generate logistical difficulties, and shortages of inputs (especially fertilizers), rising prices of agricultural products5.

Historically, technological change processes have contributed to tackling the different challenges facing agriculture, leading to real, almost immediate impacts6. The analysis of the Brazilian case shows that the adoption of new technologies -such as agricultural machinery and equipment, fertilizers, and pesticides- played a key role in the growth of agricultural productivity, notably from the 2000s onwards.

The information technology revolution, which began in the 1990s7, evolved and accelerated to the “digital transformation”, a phenomenon that involves the combined effects of several digital innovations bringing new actors, structures, practices, values and beliefs that change, threaten, replace or complement the existing rules of the game within organizations, ecosystems and sectors8. Digital technologies can be defined as tools that collect, store, analyze and share data and information digitally, using computing devices (including smartphones) and the internet connectivity infrastructure9. These digital technologies represent a new factor of production that begins to modify the bases of economic growth by transforming strategy, culture and organizational processes based on the communication infrastructure of the internet10.

In recent years, a broad digital revolution has also been established in agriculture, even though the sector has -until recently- been considered a laggard in the digitalization movement11. This digital transformation of the agriculture is characterized by the transition from analogue processes -even if already technological- to production chains structures by new digital, disruptive, convergent, and interrelated technologies12. Called Digital Agriculture or Smart Farming13, this movement is characterized by the adoption of computational and geoprocessing technologies in production activities, which allow producers to plan, monitor and manage operational and strategic activities. It is noteworthy that this transformation encompasses the entire agricultural production chain, starting with inputs, going through production, logistics, processing, distribution, and retail from seed to fork14.

Several groups of digital technologies have been building this new revolution in the sector, also known as Agriculture 4.0, among them: field and remote sensors, access to broadband mobile communication, internet of things, big data analytics, automation and robotics, computing in cloud and artificial intelligence 1)(10) . Some trends that characterize this technological movement involve the provision of new technological services structured from data, the possibility of transparency and certification offered by traceability tools and the construction of new business models, in particular, digital platforms for commercialization, whether of inputs or final products, reducing transaction costs and offering more business security15.

There are some expected benefits associated with the digital revolution in agriculture, including: increasing the sector's resilience, increasing productivity and sustainability, and providing greater transparency and reliability to activities from production on the farm to the consumer’s table16.

Although agricultural innovation has traditionally always been associated with a large number of stakeholders -such as universities and research institutions; technical assistance and rural extension companies; rural producers of different sizes and segments; suppliers of inputs, equipment, financial services; processing and distributing companies; producer associations and cooperatives9-, digitalization attracts new actors interested in exploring the new opportunities offered. Among the new entrants we have agtech startups working with digital technologies; business accelerators and venture capital investors; large information technology companies (such as IBM, Google, Meta), and operators in the telecommunications sector15.

Since the 2010s, there has been a strengthening of agtech entrepreneurship in several countries17, whether in those with a strong innovation environment marked by incentives and developed actors, as is the case in the United States and the United Kingdom, or in nations in which agriculture represents a significant portion of the gross domestic product (GDP), such as India and China18. During this period, a favorable context was established for the flourishing of startups based on agricultural technologies through the expansion of risk investors, the emergence of specific incubation and acceleration programs for agtechs, and a movement of acquisitions of startups by corporations that sought to integrate into this movement of technological transformation, through the acquisition of their skills and innovative business models.

In this research, the agricultural innovation ecosystem approach19 is used to investigate this new innovative context, understood as a complex socio-technical system in which heterogeneous actors participate and collaborate with each other in digital innovation activities20, from several dimensions: technological, social, economic, and institutional21.

The ecosystem is one of the most important concepts in the field of ecology, defined as a system formed by several components: plants, animals and the physical environment that surrounds them, such as soil and climate, which interact and organize themselves to promote a state of balance dynamic22. The ecosystem metaphor becomes richer and more contextualized when applied to the study of agricultural innovations, by including biological components, natural resources, the physical environment, and socially constructed elements (such as economic actors, interactions and relationships, culture, technologies, institutions, laws, and standards23).

The literature points out that agtech entrepreneurship is an important element in the context of an agricultural innovation ecosystem15. And, in this sense, it is understood that the mechanisms for developing and encouraging innovative startups contribute to the digital transformation of agriculture 16)(20) . Business incubators and accelerators are promising instruments to support the creation, development, and maturation of technology-based startups24. These initiatives are structured around educational activities conducted in groups, during a defined period -a few months, in general-, associated with the offer of targeted mentoring for each participating startup25.

The objective of this research was to study the specificities of the agricultural sector with regard to the digitalization movement, investigating in particular the contribution of startups in this process. The aim is to promote an overview of the contribution of agro-digital entrepreneurs to the digital transformation of agriculture. A case study was conducted with startups participating in the Techstart Agro Digital program in the 2020/2021 cycle26. This open innovation and acceleration program is co-carried out by Embrapa Agricultura Digital and Venture Hub since 2019, and seeks to explore the opportunities offered by the digitalization of the agricultural sector.

Techstart Agro Digital is structured around interventions typical of an acceleration program, such as sessions to disseminate content and entrepreneurial techniques; technical and business mentoring, and access to services and technologies at subsidized prices; pitch preparation workshops; examination boards with the participation of researchers, professionals and investors working in the agricultural sector27. The aim is to establish spaces for exchanging knowledge and experiences, as well as networking moments to expand the access of agtechs to various actors in the innovation ecosystem. All these benefits are offered in exchange for equity participation of the startups, negotiated on a case-by-case basis.

The scope of the research involved a survey with entrepreneurs participating in the 2020/2021 batch of this program, to establish a profile of the startup, its technological offer and operating markets, as well as their perceptions related to future trends in the sector. This article has five sections in addition to this introduction. The next section presents the methodology used in the analysis and, subsequently, the results found, a discussion, and the conclusions of the study are presented.

2. Materials and Methods

This research aimed to answer a central question: what is the contribution of agtechs to the digital transformation of the agricultural sector?

To answer this question, a case study was promoted, surveying the perceptions of young companies based on agricultural digital technologies participating in the Techstart Agro Digital program during the 2020/2021 batch. The case study approach is suitable for investigating a contemporary social phenomenon over which the researcher has no control28, to seek an understanding of its dynamics through more detailed and exploratory questions and analyses. In this sense, it is understood that the search for an understanding of the contribution of startups to the digitalization of the agricultural sector is a theme consistent with this approach.

This research followed the reference parameters of the study “Digital Agriculture in Brazil”14 based on the selection of a specific target audience -the 26 startups participating in the Techstart Agro Digital program during the 2020/2021 batch-. Data collection was conducted from an online questionnaire in survey format using mostly quantitative data and qualitative elements (the latter identifying the entrepreneurs' perception of future trends in agtechs sector). A strategy of mixed methods29 was employed with the integration of qualitative and quantitative data, in order to obtain a pragmatic approach to address a central issue: insights of the contribution of agtechs to the digitalization of agriculture. Qualitative data tends to be open-ended and subjective, while quantitative data usually includes closed-ended responses and objectivity29. This combined strategy based on the triangulation from different data sources allows more possibilities of obtaining deeper insights than isolated methods.

The structure of the online form is presented in Table 1.

The questionnaire involved different types of questions (alternatives, multiple choice and discursive) grouped into the following thematic axes:

(I) Identification of each agtech;

(II) Segment and operating profile: segment (agriculture, livestock and forestry); types of digital solutions offered; agricultural chains served; customer categories (farmers, traders, consultancy companies, cooperatives, among others); the most prominent technological fields and markets;

(III) Data science expertise: startup's performance in data science, an optional question;

(IV) Perception of the entrepreneurs (qualitative): advantages provided by digital technologies by agricultural sector; challenges and/or limitations for its commercialization/diffusion, and perspectives of using different types of technologies in digital agriculture.

It is worth highlighting that the structure and topics of the consultation were analyzed and validated by experts regarding relevance and form of presentation. The questionnaire was built at the Google Forms platform, and sent by email between December 15, 2020 and January 5, 2021. The Supplementary Material 1 presents the complete survey questionnaire. The main results and analyses are presented below.

Table 1: Structure of the online consultation form of the agtechs at Techstart Agro Digital 2020/21

Notes: *According to IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.**such as: farmers, companies, cooperatives, governments, among others.***UAVs, drones, satellites, nanosatellites, among others.****Seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, biological control agents and water.

3. Results

Founders of 30 agtechs participating in the 2020/2021 cycle of the Techstart Agro Digital program were invited to participate in the online consultation. A voluntary return of 26 fully completed questionnaires was obtained, equivalent to 86.6% of the selected sample. The results obtained in the different thematic axes are presented and discussed below.

3.1 Profile of Agtechs: Location and Production Chains of Operation

From the information collected in the thematic axes “identification” and “segment and operating profile” it was possible to establish a profile of the responding agtechs. In relation to time of experience, 65.4% indicated that they have been operating for at least five years, a profile consistent with an acceleration program that seeks startups with minimally viable products and services and/or with first sales.

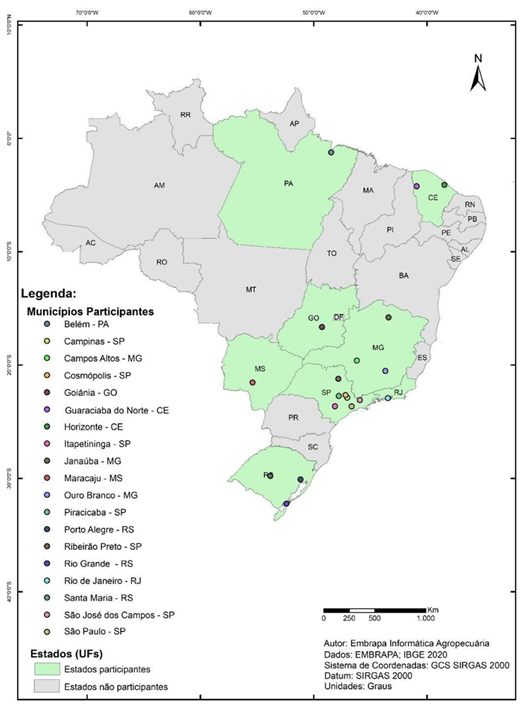

The analysis of the participants' location presents a distribution across seven Brazilian states, as shown in Figure 1. There is a concentration in the southeast of the country (69%) and in São Paulo (54%). The percentage distribution in the other states is: Minas Gerais (11%), Rio Grande do Sul (11%), Ceará (8%), Rio de Janeiro (4%), Mato Grosso do Sul (4%), Goiás (4%), and Pará (4%).

The responses showed that many of the responding agtechs do not limit their operating range to the municipality or state of “headquarters”: 42% of them operate in more than one region of the national territory, or throughout Brazil. It was indicated that 77% operate in the southeast; 65% in the midwest; 62% in the south; 54% in the northeast, and 42% in the northern region, which reveals a slight concentration of activity in the center-south axis of the country.

The analysis of the spatial distribution of the location of startups and their area of activity allows us to infer the diffusion and adoption of digital technologies in different regional production arrangements.

Regarding the production chains in which the responding startups operate, it was found that some of them operate in more than one segment. The results indicated that the majority of agtechs operate in the agriculture sector (73%). Among these, totaling 20 startups, there are three main crops mentioned: soybeans (60%), corn (50%) and wheat (40%). It is noteworthy that these three agricultural crops (soybeans, corn and wheat) make up almost 90% of the harvested area in Brazil and 91% of the grain production harvest30. Other crops indicated were: beans and vegetables (both with a proportion of 20%), cotton, rice and coffee (both with a proportion of 15%), English potatoes, tobacco, sunflower, apple, cassava, mango and millet (all with a proportion of 10%).

Around 23% of respondents operate in livestock and forestry, each. Livestock activity is mainly focused on cattle farming, with 50% of respondents working with beef cattle and 37.5% with dairy cattle; 25% work in poultry farming, and 12.5% work in pig farming. In forestry activities, 63.6% of participants indicated that they operate in the segment of eucalyptus, 54.5% with pine and 9.1% with other exotic species. It should also be noted that 54.5% also indicated that they work with native species. The research also showed that many agtechs serve clients working with more than one species (eucalyptus, pine and native trees).

3.2 Operating Market: Customers, Types of Products/Services, and Data Science

Among the main categories of customers of agtechs participating in the survey, the following stand out: farmers (76.9%), associations, cooperatives, unions or non-governmental organization (NGOs) (69.2%), and municipal, state and/or federal governments (38.5%), service providers (30.8%), livestock farmer and silviculture (23.1%), with the same participation, and equipment and machine companies and financial institutions with equal percentage (11.5).

Regarding technological fields of operation, 73% of the responding agtechs supply cell phone applications, computer programs or digital platforms for managing property or agricultural production. Secondly, 42% of respondents stated that they offer services based on data or images about plants, animals, soil, water, climate, diseases or pests provided by sensors in the field. The third most cited field of activity -with 35% of respondents- involves working with data or images of the farm, provided by remote sensors, such as satellites, airplanes, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and/or drones.

Figure 2 presents the technological fields of operation of the responding agtechs.

Digital technologies can be categorized into three groups -low, medium and high complexity of applications- which directly influence decision-making regarding acquisition and use by Brazilian farmers31. According to the literature31 the following technologies are categorized as low complexity: internet and connectivity/wireless; mobile apps, digital platforms and software; global positioning systems, and digital maps. Medium complexity applications are based on proximal and field sensors, remote sensors, embedded electronics, telemetry, and automation. High complexity applications are developed with deep learning and internet of things, cloud computing, big data, blockchain and cryptography, and artificial intelligence.

A previous study31 identified that between 60% and 70% of farmers use low-complexity digital technologies such as applications and digital platforms to support property management, purchase of inputs and commercialization of production; between 16% and 22% use medium complexity technologies, such as data from remote and field sensors for mapping and agricultural monitoring; and 5% to 9% use automation and embedded electronics, still classified as technologies of medium complexity, even though they are more sophisticated and evolved than those previously mentioned.

Even though there are connectivity restrictions (both in terms of coverage and transmission of data), the use of cell phones is already a reality in Brazilian rural areas, where 71% of the farmers already use applications aimed at managing their crops or selling products, whether directly on the property or via associations or cooperatives31.

It is noteworthy that “data-driven agriculture”32 is being established by reducing the costs of collecting, analyzing, and storing data in agriculture, whether through sensors and computers at more affordable prices, through access to connectivity, and cloud computing. This technological trend has allowed the generation of unprecedentedly large amounts of data on modern farms, collected in the process of digitalization of field and management operations.

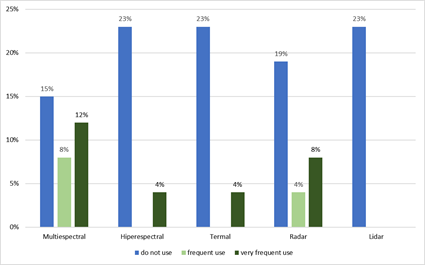

Regarding this matter, two questions of the survey -optional- explored aspects related to the use of remote sensing associated to commercialization of products and/or services based on images and/or data obtained by drones, UAVs, nanosatellites, satellites and/or planes, highlighting the sensor most frequently used. Approximately 35% of survey participants answered this question, as shown in Figure 3.

The analysis of the responses indicates the combined use of images and data for digital agriculture, with the multispectral sensor being the most used. Radars had the second highest frequency of use. Regarding non-use, 23% of startups do not use hyperspectral, thermal and LiDAR, and 15.4% do not use multispectral.

It is worth noting that the increasing evolution of remote sensors has been offering a greater range of agro-environmental mapping and monitoring applications through increased spatial, temporal, and spectral resolution. Sensors that initially had a spatial resolution greater than 30 meters now have a sub-metric pixel size. Previously restricted to fortnightly or monthly revisits, today they can map the same area daily. If previously they focused on the visible (RGB) or near-infrared bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, today they have up to a hundred bands at different wavelengths.

These new remote sensors -embedded in satellites, nanosatellites and UAVs- have been used by Brazilian farmers to assess soil characteristics and fertility, monitor irrigation and drainage processes, and map land use and cover32. There are also increasing applications of spectral vegetation indices, such as the traditional NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) and the EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index), an adjusted version of the NDVI with a focus on denser vegetation, which allow decision-making on land management, soil or agricultural crops in near real time.

More innovative applications involve the use of hyperspectral sensors, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), fluorescence spectroscopy, and thermal spectroscopy. These conditions, associated with new applications based on machine learning and computer vision algorithms, allow the collection of more accurate data and images and the development of more complex tools, such as evaluating soil properties or a specific agricultural crop through the analysis of specific compounds, molecular interactions, and biophysical or biochemical characteristics.

However, even with the increasing availability of images at different spatial, temporal, and spectral resolutions, the agricultural sector has not yet fully implemented remote sensing technologies due to knowledge gaps regarding their sufficiency, suitability, and technical-economic feasibility33.

3.3 Applications and Perception of Advantages and Benefits

The responses obtained regarding types of applications offered were quite heterogeneous, involving a wide distribution of categories. The main purposes/applications highlighted by the respondents were: production and/or productivity estimates (53.8%); obtaining information for planning and managing rural properties (53.8%); certifications and traceability of agricultural products (42.3%); disease detection and/or control (38.5%); mapping and land use planning (38.5%); pest detection and/or control (34.6%); detection and/or control of areas with water deficit (30.8%); detection and/or control of operational failures (30.8%), and detection and/or control of weeds or nutritional deficiencies (26.9%).

The research investigated three groups of digital technologies in more detail: (i) web applications and services; (ii) field sensors -soil, plants, animals, machines and equipment-, and (iii) remote sensors -satellites, drones and UAVs-. Applications and web services are those that present the greatest perception of benefits from the perspective of entrepreneurs, highlighting greater access to direct sales to consumers (84.7%), greater ease of marketing products (84.6%), better planning of daily activities (46.2%) and greater increase in profit (42.3%).

Field sensors/machines/equipment are associated with benefits related to greater optimization in the use of inputs (53.8%) and greater labor efficiency to carry out activities (38.5%), together with increased productivity (34.6%), greater cost reduction (27%), and greater profitability (26.9%).

Remote sensors are associated with benefits involving reduced environmental impact in production (38.5%), greater cost reduction (34.6%), greater productivity (30.8%), and better planning of daily activities (30.8%).

3.4 Challenges, Limitations and Perspectives for Digital Agriculture

The last thematic axis of the survey regarded the perception of entrepreneurs in relation to the challenges and/or limitations for the commercialization or provision of services in digital agriculture. Two challenges received most mentions: the availability of internet connectivity in rural areas and users' access to training in digital agriculture technologies. And these issues have been prioritized by federal government policies for some years now 15)(25) .

Obtaining qualified and specialized external labor was also a frequently cited challenge. Other challenges for the adoption of technologies by the producer were named, such as the difficulty in proving the benefits for the farmer, the value of the investment for acquiring technologies and hiring service providers by farmers, and the operational and maintenance cost of machines, equipment, and applications. Another point to improve would be access to credits for the purchase of machinery and equipment by service providers and farmers.

The last item of the consultation referred to the prospects for incorporating new technologies in digital agriculture into the portfolio of the agtechs participating in the study. In relation to “data-driven agriculture”32, the answers emphasized the use of data and/or images, whether captured by field sensors (46%) or remote sensors -satellite, plane, unmanned autonomous vehicles (UAVs) and/or drones (42%)-. Other technological fields mentioned were artificial intelligence (42%) and machine learning (39%), perhaps in the direction of data analytics. Cryptography and blockchain were also mentioned (35%).

4. Discussion

The startups that participated in the study are concentrated in the southeast region of the country (69%), mainly operating in agriculture (77%), and working mainly with cell phone applications, computer programs or digital platforms (73%), generally focusing on management. This distribution is coherent with the last study mapping agtechs in Brazil34 by location and field of operation.

The results showed that most of the digital applications offered by the startups -73% of them- had a low level of complexity (apps and digital platforms such as marketplaces)31, highlighting an offer that is still unsophisticated in terms of the technological drivers that characterize digital transformation such as sensors, access to broadband mobile communication, internet of things, big data analytics, automation and robotics, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence 1)(10) .

The adoption of digital technologies of low complexity is aligned with recent researches. McKinsey Consulting has been carrying out a survey with agricultural producers since 2018 about their perceptions of market, challenges, and technological innovations35. This research showed that, after the pandemic, technology adoption started through their purchasing journey, with the use of instant messaging -WhatsApp, being particularly popular in Brazil- and digital marketplaces, especially in the acquisition of equipment.

Growers in South America are more open to digital interaction than other countries35 and the level of adoption of digital agriculture technologies is led by Brazil and Argentina, followed by Uruguay and Chile36. The access to mobile phones by growers combined with the support of the private sector and public institutions enabled a rapid adoption of agriculture apps.

Recent data collected in 202435 indicates that countries with larger farm sizes, such as Brazil and the United States, are leading in adoption of digital technologies, including more complex ones, such as digital agronomy tools (yield monitoring, fertility prescription, planting and seed optimization and irrigation) and precision agriculture, with United States leading adoption rates, followed by Brazil, Europe and India.

The only applications of higher technological complexity offered by the startups participating in our survey (conducted in 2021) involved the use of data or images about plants, animals, soil, water, climate, diseases or pests provided by sensors in the field, and data or images of the property, provided by remote sensors. These findings are aligned with the recent studies, especially related to remote sensing 35)(36) . Even in 2024, automation and robotics -high complexity technologies- have a lower adoption rate35, which explains why agtechs were starting their offer by offering low complexity digital technologies in the market, as a strategy to gain scale and grow.

It appears, however, that there is already a percentage of startups working with technologies even more sophisticated, structured by the collection and analysis of large volumes of data and the use of remote sensing images -35% of the responses-. This percentage might increase, given the perspectives of technological evolution mentioned by the respondents.

Despite the large number of technological options available for agricultural producers, it is noteworthy that they consider that the return on investment (ROI) related to digital technologies adoption is still uncertain and demands high maintenance investment35. Because of that, there is a concern about having a clearly demonstrated ROI in the application of the technologies in the farm before the acquisition and implementation in the field35. One opportunity for agtechs is to offer tailored solutions to different productive chains and by this to get a better ROI and effective results.

Among the main challenges indicated by agtechs regarding their technological performance and commercialization of products and services, the following stand out: insufficient rural connectivity infrastructure; limited user access to training in digital technologies; difficulty of obtaining qualified labor, and the need to establish business models that value the benefits of adopting digital technologies in the field. These obstacles are also cited by recent literature in regard to South America36.

There is a very limited connectivity infrastructure in remote areas with small populations in Brazil37, areas with less commercial interest for telecommunications operating companies. Even though internet access in rural households does not reflect the situation of rural properties, located further away from municipalities, this is an insightful indicator. Albeit slowly, the distance between urban (85.6%) and rural (73.8%) households in terms of connectivity is decreasing, both with growing trends38. In this sense, public policies and community strategies play an important role and this topic is already part of the agenda of Brazilian policy makers in their quest to promote the development of rural regions.

Regarding adoption of high complexity digital technologies in the farms, 77% of users of rural municipalities access the internet from a cell phone, compared to 56% of users in urban areas37. Being less expensive devices, and considering its utility to day-by-day life, smartphones represent a more affordable investment, especially with the increase in connectivity services and decrease in their costs. But the small screen and limited processing capacity restrict the access to sophisticated information based on data-driven tools for precision agriculture and digital agronomy.

The analysis of the profile of startups participating of Techstart Agro Digital program and their perception of market and future perspectives offered important insights to understand their influence on the digitalization of the field. Although digital entrepreneurship can serve as a key driver for the increased supply of digital solutions for agrifood systems, it depends on the quality of its surrounding innovation ecosystem. Several building blocks should be provided, such as market accessibility, qualified human capital, financial support, regulatory framework, research and innovative culture, and soft and digital skills20.

5. Conclusions

The results of this research highlight the technological offer of the consulted agtechs as their main contribution today to the digital transformation of the countryside, bringing digital technologies closer to the universe of rural producers.

The locational concentration of the agtechs -in the southeast region of the country (69%)- reflects the profile of Brazilian territorial development, especially with regard to the adoption of information technologies and the entrepreneurial movement. And the main markets indicated -southeast, central-west and south- correspond to the main productive regions of the country, as expected.

The technological offer mainly involves low-complexity products and services, such as digital applications. This technological profile is consistent with the type of internet access in rural households today (mostly mobile) and with the level of training and digital skills of most Brazilian rural producers today. The main benefits perceived by entrepreneurs related to the adoption of digital technologies by farmers are improvements in marketing process (greater access to direct sales to consumers, greater ease, and increased profitability) as well as management of the property, regarding better planning of daily activities.

There is still little information and effective studies on the conversion of the adoption of these technologies into productive benefits, even though entrepreneurs indicate several possibilities associated with each technological category. However, in general, producers consider that the return on the investment in digital technologies is still uncertain.

Literature shows that startups are a key factor to increase the offer of innovative digital technologies to agriculture and they grow from a fertile and supportive environment. To develop a significant market for digital-based technologies for agriculture, an innovative agricultural ecosystem should be strengthened to facilitate collaboration to generate gains for the actors involved: producers, corporations, universities and research centres, government and policy makers, extension agents, cooperatives, and consumers.

Public policies can create the basis for the development and dissemination of new, more complex applications by agtechs. Among the initiatives would be encouraging and accessing the acquisition of devices and access to quality connectivity services and the development of digital and technological skills for professionals working in the field. Incentives to collaboration of different actors to generate technological innovation can also be provided by government and development agencies.

The formulation of public policies and other mechanisms to encourage agricultural innovation, in different Brazilian regions, could provide infrastructure, education, and skills. Also, the development of tailored solutions for different productive chains could lead -in the long run- to an increase in the demand for more complex technologies. The adequate incentives to build a virtuous collaborative innovation ecosystem in Brazilian agriculture would provide more effective digital applications and better results in the field, meeting the promises associated with the digitalization of the sector.

The results of this research can contribute to overcome the technological challenges identified in the survey and encourage digital agriculture development, to increase the technological offer of agtech entrepreneurs and its adoption. Future studies can advance in this discussion, either investigating the adoption of digital technologies in the agricultural sector in census-type surveys considering different categories of technologies and complexity levels, or mapping different regional innovative ecosystems in Brazil to support specific public policies, identify local demands, and develop tailored solutions.