1. Introduction

In a genotyping pipeline, sex determination through genotyping serves as an effective quality control (QC) measure that offers a straightforward QC check to ensure that the genotyped DNA corresponds to the reported animal1. Gender classification mistakes due to incorrect sample identification, data entry mistakes, or genotyping errors can cause delays in genetic progress of breeding programs2.

The sex-calling algorithm that is used in Affymetrix chips is one of the ways of determining sex and is available in the proprietary Axiom Analysis SuiteTM software. This algorithm is named as cn-probe-chrXYratio_sex. This method of sex determination is based on the ratio of the average probe intensity of non-polymorphic probes on the Y chromosome to those on the X chromosome, excluding the copy number probes within the PAR regions of both the X and Y chromosomes. Another approach is through X chromosome heterozygosity3. Sheep [Ovis aries] have 26 pairs of autosomal chromosomes and two sex chromosomes: X and Y. Females, with two X chromosomes, display heterozygosity, whereas males, with one X and one Y chromosome, are hemizygous for the X chromosome3. However, an exception is the pseudoautosomal region (PAR), a region of sequence homology between the X chromosome and Y chromosome that is involved in pairing, recombination, and segregation during meiosis, where males can also be heterozygous 4)(5) . It is important to identify the PAR region for the correct determination or confirmation of sex from X chromosome genotypes2. Although sex prediction using SNPs from both X and Y chromosomes is optimal, not all commercial SNP chips contain Y chromosome markers. This is because assembling the mammalian Y chromosome has been quite difficult, as it contains a lot of repetitive DNA sequences that complicate sequencing and assembly 6)(7) . In the past, it was rather challenging to obtain high-quality assembly of the Y chromosome in the Bovidae family. However, a recent study by Olagunju and others7 reported contiguous, high-quality Y chromosome assemblies in both sheep and cattle, providing a new opportunity for the inclusion of Y chromosome markers in sex prediction. In the absence of Y chromosome markers, sex prediction based on X chromosome SNP heterozygosity alone requires careful exclusion of PAR SNPs1 and the inclusion of only non-pseudoautosomal region (nPAR) SNPs.

The main goals of this study were to identify the PAR region on the X chromosome in sheep using the ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0 genome assembly and to describe a method for predicting sex in sheep based on the proportion of heterozygous SNPs in the nPAR region of the X chromosome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Training Population

The training dataset consisted of 105 male and 105 female sheep from five breeds (i.e. Corriedale, Creole, Corriedale Pro, Finnish Landrace, and East Friesian) and three crossbreeds (Finnish Landrace × Corriedale, East Friesian × Corriedale, Finnish Landrace × East Friesian), genotyped using the Ovine Infinium® HD SNP BeadChip (606 006 SNPs; Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). This dataset was used to identify the PAR region on the X chromosome.

2.2 Validation Population

Furthermore, a test dataset consisting of 229 sheep (114 males, 115 females) from three breeds, Corriedale (n=105), Australian Merino (n=67), and Texel (n=57), genotyped using the OvineSNP50 BeadChip (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for validation. Previously, animals with parentage conflicts involving at least one parent were excluded from further analysis due to potential DNA misidentification.

2.3 DNA Extraction

Blood samples were collected through jugular vein puncture from weaned lambs using K2 EDTA anticoagulant tubes. Genomic DNA was subsequently extracted8 from the samples.

2.4 Animal Welfare

Animal handling and blood collection procedures were approved by the INIA Animal Ethics Committee (approval number INIA_2018.2) in accordance with Uruguayan Law 18611.

2.5 Quality Control and Statistical Analyses

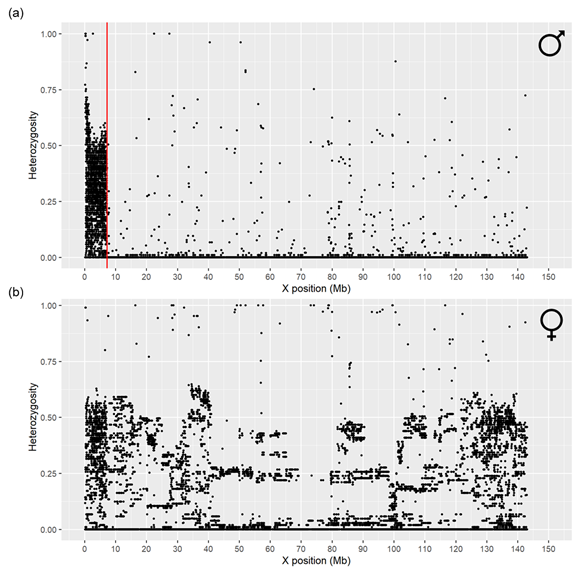

Our initial dataset contained 25,883 SNPs situated on the X chromosome based on the ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0 sheep genome assembly. Genomic data quality control was performed using preGSF90 software9. A total of 23,879 SNPs remained after call rate (>0.90) and MAF (>0.01) quality control steps according to Zhan and others2; SNP observed heterozygosity (Ho) was calculated for male and female populations in the training dataset. The ggplot2 package from R software10 was employed to plot the results. The pseudoautosomal boundary (PAB) was established through visual inspection without the use of any software tool, while the PAR region was identified based on the SNPs exhibiting high heterozygosity rates in males. The Y chromosome SNPs were unavailable for analysis since our array did not contain them.

Subsequently, heterozygosity data from the nPAR region was used to determine the sex of animals in a separate dataset containing individuals with recorded sex. The same quality control criteria from the training data were applied to this population, which led to a final set of 1,103 SNPs. The Irish Cattle Breeding Federation (ICBF) provides sex prediction guidelines based on X chromosome nPAR SNPs heterozygosity rates1: a rate of ≤ 5% indicates a male, ≥ 15% indicates a female, and rates between 5% and 15% are considered ambiguous for sex determination.

The R caret package11 was used to generate a contingency table to evaluate sex prediction accuracy, while the R pwr package12 was used to conduct a chi-square post hoc power analysis to assess sample size for detecting recorded versus predicted sex differences. Cohen’s w was used to quantify the effect size.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 PAR Region Determination

The boundary separating the PAR and nPAR regions on the X chromosome (PAB) was identified through visual inspection of the scatter plot for males (Figure 1a). Males presented an average heterozygosity (Ho) of 0.32 among the first 2009 SNPs (0.00 to 7.24 Mb), while nearly all the remaining 21,870 SNPs (7.62 to 143.12 Mb) showed a Ho close to 0. In contrast, females displayed an average Ho of 0.32 across the entire X chromosome (Figure 1b).

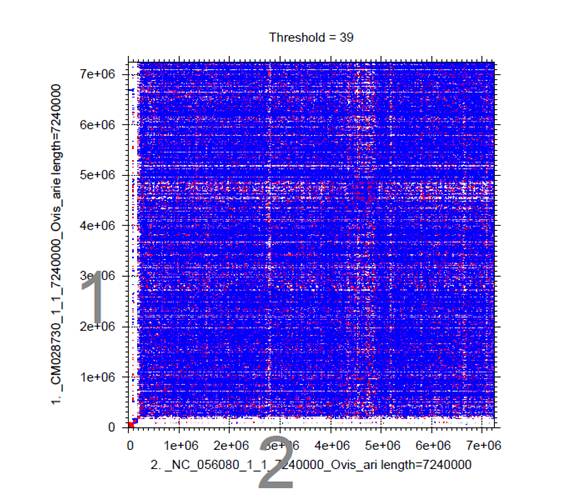

Previous studies, using the Oar v4.0 reference genome assembly, reported the sheep PAR region extending from 0 to 7.04 Mb13. Our results, based on the ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0 genome assembly, identified this region extending from 0 to 7.24 Mb, which matched the previous research findings. We analysed the X chromosome region from 0 to 7.24 Mb between the ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0 sequence (NCBI RefSeq assembly: GCF_016772045.1) and the current reference assembly, ARS-UI_Ramb_v3.0 (NCBI RefSeq assembly: GCF_016772045.2), using MAFFT software14, and found a strong sequence alignment between them (Figure S1 in Supplementary material). The Ovine Infinium® HD SNP BeadChip data indicates that the PAB region extends from the oar3_OARX_9495 SNP (the last PAR SNP at 7.24 Mb) to the oar3_OARX_7679966 SNP (the first nPAR SNP at 7.62 Mb). These findings are crucial because they define two distinct regions on the X chromosome: the PAR region and the nPAR region, with the latter one functioning for sex determination purposes.

3.2 Sex Prediction

Table 1: Contingency table for recorded and predicted sex for males and females

| Predicted_female | Predicted_male | |

| Recorded_female | 102 | 13 |

| Recorded_male | 1 | 113 |

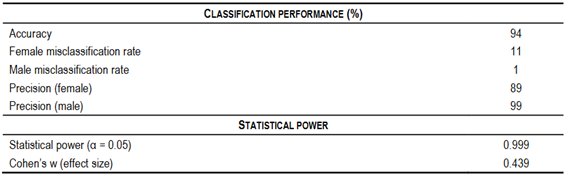

The validation population contained 229 animals, 14 of which had a recorded sex that differed from their predicted sex (Table 1), indicating the test achieved 94% accuracy in sex prediction (Table 2). The results showed that thirteen recorded females were classified as males, while one recorded male was classified as female, which resulted in precision rates of 99% for males and 89% for females (Table 2).

The post hoc power analysis found a Cohen’s w effect size of 0.439, indicating a medium effect. The power of the test was calculated to be 0.999 with 1 degree of freedom and a 0.05 significance level, well above the conventional threshold of 0.8. These results suggest that the study is quite powerful and therefore has a high ability to detect real differences if they exist (Table 2). Nevertheless, it is important to be careful when generalizing these results to other breeds of sheep. Our validation dataset consisted of Corriedale, Australian Merino, and Texel sheep, which may not entirely capture the breed-specific genomic variation, particularly on the X chromosome. It is advisable to conduct further validation in a larger number of sheep breeds to confirm the robustness of our approach.

A more detailed analysis of the data showed that the recorded male classified as female had a Ho of 0.42 (462 SNPs out of 1,103), and all the recorded females classified as males had a Ho of 0 (0-3 SNPs out of 1,103). Physical examination to confirm the sex of the animals was not possible as none of them are still alive. However, the pedigree file indicated that 12 out of the 13 recorded females classified as males were listed as dams, thus confirming their true female status. On the other hand, the recorded male classified as female was only listed as a lamb in the pedigree file, thus its true male status could not be ascertained. This is most probably due to stud flock management practices where male lambs not selected as sires are culled. Additionally, when this lamb was sampled, the laboratory received two blood tubes with the same identification, which potentially originated from different animals yet only one sample underwent genetic testing. These findings suggest that the recorded sex of these animals is probably correct, and sample mislabelling may have contributed to errors in genotype data.

In addition, the shipment records indicated that four recorded females classified as males and the recorded male classified as female were shipped together in the same 96-well plate, with some of them placed in adjacent wells, which may have caused identification errors. Also, six more females classified as males were shipped together in another 96-well plate, which could suggest a mistake during handling or processing. Since paternity verification was not available for these samples, we cannot state whether the correct samples were genotyped. The other three females classified as males were processed in separate shipments, indicating that biological factors may also be contributing to misclassification rather than sample mislabelling.

Our study achieved a 94% accuracy rate, which represents a significant improvement compared to other sex determination methods such as visual inspection and PCR-based sexing assays15. Nevertheless, it is lower than the accuracy level observed in other SNP chip array studies2 and studies based on GBS data3. Nonetheless, the overall high accuracy obtained indicates that our approach is quite reliable, especially for males, who are classified with very high confidence (99% precision).

Sample mislabelling is a possible reason for some of the errors, but biological factors could also contribute to the 11% female misclassification rate. Sex prediction in females is based on higher observed heterozygosity values (Ho ≥ 15%) compared to males (Ho ≤ 5%). Since genetic diversity decreases due to inbreeding, some females may not attain the heterozygosity threshold for classification, thus increasing their chances of being misclassified as males or ambiguous sex.

Breed specific differences in X chromosome structure and heterozygosity may also explain discrepancies in female misclassification rates. Merino sheep from stud flocks have been strongly selected for reduced fibre diameter, while animals from an experimental unit have been selected for a combination of traits including fibre diameter, body weight, and clean fleece weight, intensifying directional genetic pressure16. Although Corriedale is a dual-purpose breed, it has also undergone intensive selection. In this study, Corriedale samples were drawn from registered stud flock animals and from an experimental unit comprising two divergent lines selected for resistance to gastrointestinal parasites17, both populations showing strong genetic progress. The Texel samples, on the other hand, originated from a central progeny testing unit, which receives rams from stud-breeders for evaluation, but does not implement any selection criteria. These differences in selection history and breeding objectives probably contribute to structural variation in the X chromosome and influence heterozygosity patterns. Consequently, breed-specific variation may affect the heterozygosity threshold used for sex prediction, resulting in different misclassification rates across breeds. Further validation with larger and breed-specific datasets will be important to fully understand the impact of X chromosome variability on SNP-based sex classification.

Though it is recommended to use SNPs from both the X and Y chromosomes for sex prediction, our array did not include Y chromosome SNPs. Previous studies 2)(3) 18 have shown that relying on X chromosome SNPs alone can be problematic in predicting sex due to multiple factors. The genotyping errors that occur because of problems with sample handling can be considered as random errors which may lead to incorrect sex assignment. Also, inbreeding may result in misclassification, especially among highly inbred females who inherit the same intact X chromosome from a common ancestor, which gives them X chromosome profiles similar to those of males18. Although the average pedigree inbreeding coefficient for Uruguayan sheep is relatively low (1.1%), with Corriedale at 1.35% and Merino at 0.63%, these values are based on our own calculations using registered stud flock animals from genetic evaluations. Reduced genetic variation in more inbred populations may increase the chances of females not meeting the heterozygosity threshold for accurate classification. Sex chromosome aneuploidies, such as XO in females (where there is only one X chromosome) and XXY in males (where there is an extra X chromosome), have been observed in sheep 19)(20) 21. Even though these conditions are quite rare, they involve abnormalities in the number of sex chromosomes, which may result in atypical X chromosome profiles. Although we did not directly analyse sex chromosome aneuploidies in our dataset, a study using a sample of 146,431 juvenile cattle reported the frequencies of XO in females at 0.0048% and XXY in males at 0.0870%22. Future research including SNP genotype intensity data may be used to determine the frequency of such aneuploidies in Uruguayan sheep. Intersex conditions such as XX sex reversal and androgen insensitivity syndrome, although rare, also pose a challenge. In XX sex reversal, the individuals have an XX karyotype (XX) but have male gonadal and/or phenotypic sex23, whereas in androgen insensitivity syndrome, the individuals have an XY genotype but have hormonally active but retained testes and develop female external genitalia due to defective androgen receptors24. These rare anomalies can result in chromosomal-phenotypic sex discordance, which may decrease the reliability of SNP-based classification. Importantly, these genetic and physiological factors are not independent but can interact, as inbreeding may increase the incidence of sex chromosome abnormalities and intersex conditions, which will make classification more difficult. Together, these limitations highlight the need to use markers from both the X and Y chromosomes to improve the accuracy of sex prediction methods.

The sex prediction method evaluated in this research study demonstrates practical value for commercial sheep genotyping pipelines. The test provides an accurate way to predict animal sex when Y chromosome information is missing and simultaneously helps detect animals with aneuploidies or intersex conditions. Genetic analysis reliability and breeding programs effectiveness would rise because misclassification risks would decrease through this approach.

The integration of sequencing data with SNP-based sex prediction represents a promising direction for future research. SNP arrays represent a cost-effective solution, but sequencing technologies deliver enhanced accuracy. These technologies allow the direct analysis of sex chromosome sequences, which leads to better identification of genetic anomalies. This approach would help validate results and identify errors while designing better SNP marker panels. An example is the recent high-quality Y chromosome assembly for sheep developed by Olagunju and others7, that shows promise for integrating Y chromosome markers in sex prediction.

4. Conclusion

We determined the location of the PAR region on the sheep X chromosome using the ARS-UI_Ramb_v2.0 genome assembly and described a method which uses X chromosome SNPs to predict sex. This method generates precise sex predictions across various sheep breeds, making it an effective quality control tool in the absence of Y chromosome data. The method demonstrated positive results but requires further research using sequencing data along with studies on genetic anomalies, like aneuploidies and intersex conditions, to achieve better validation and refinement.