1. Introduction

Dysdercus Audinet-Serville is a large genus of plant bugs, and the only genus in Pyrrhocoridae that includes insects of economic importance, distributed across subtropical, tropical, and some temperate regions of both the Old and New World1. About 75 species are recognized worldwide and are collectively known as cotton stainers2. The cotton stainer bug or arrebiatado (Dysdercus peruvianus Guerin-Meneville) is an economically important species in Order Hemiptera and a cotton pest (Gossypium hirsutum L.)3 with damages in cotton capsules and seeds; it spoils the cotton fibers, and is also a vector for phytopathogenic microorganisms and may result in great losses in cotton production 4)(5) . This species is considered a cotton pest in Peru2, and became one of the most economically important pests in the 1980s, causing losses that exceeded 30% of the harvest6.

The need of several countries in the world, especially in Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia, to develop intensive agriculture to feed the increasingly large population leads to the use of synthetic pesticides for the control of pests and diseases, many sometimes without any kind of regulation7. Most of these pesticides are organophosphates such as methylparathion, phorate, dimethoate, and other non-phosphorus such as dithiocarbamates, carbamates, triazines, pyrethroids, and neonicotinoids, which negatively affect the health of humans, and in some cases residues have been detected in crops in Latin America 8)(9) 10. Worldwide, pesticide use amounts to 4 million tons, with around 385 million acute poisonings reported in 2020, of which about 11,000 were fatal11. In Peru, the reported cases of acute pesticide poisoning (APP) according to epidemiological weeks (EW) Peru 2020-2024 (Until 01/January/2024) were 6,32012. This is why there is a special concern in the world, and particularly in Peru, to carry out ecological alternative research and agricultural and health practices that are best suited to Integrated Pest Management, such as the use of plant extracts, which are more sustainable to the environment and less harmful to human and animal health7. In this regard, there is a wide diversity of organic products as pest controllers, such as essential oils (EOs) 13)(14) and others, such as lignans and amides produced by Piperaceae species, that have demonstrated potential insecticidal activity15. An extensive review in this regard has recently been published by de Albuquerque and Rocha16.

In Brazil the effect of EOs of some plant species belonging to the Atlantic Forest biome was studied in the control of several insect vectors of metaxenic diseases and pest insects such as D. peruvianus16. EOs of leaves of Ocotea indecora (Schott) Mez. (Lauraceae)17, Myrciaria floribunda (H. West ex Willd.) O. Berg (Myrtaceae)18, Zanthoxylum caribaeum L. (Rutaceae)19, Pilocarpus spicatus Saint-Hilaire (Rutaceae)20 and Persea venosa Nees & Mart. (Lauraceae)21 showed activity against this species. Likewise, hexanic extracts of fruits and flowers of Clusia fluminensis Planch. & Triana (Clusiaceae)22, and semi-purified fractions of hexane crude extract from stems of C. hilariana Schltdl.3, and an insecticidal nanoemulsion, containing apolar fraction from fruits of Manilkara subsericea (Mart.) Dubard (Sapotaceae), were considered active against D. peruvianus23. However, there are other species of Dysdercus that cause considerable yield loss by feeding on the young leaf and cotton seeds24, such as red cotton bug (D. cingulatus Fabricius, D. maurus Distant), but Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott (Araceae)25 and Croton urucurana Baillon (Euphorbiaceae)26 showed insecticidal activity, respectively.

Peruvian studies on insecticidal activity against D. peruvianus are relatively recent and scarce. Lyophilized aqueous extracts of bark and leaves of around 20 plant species, mostly of American origin, were tested on Aphis gossypii Glover, Bemisia tabaci Gennadius and D. peruvianus, cotton pests, observing that for the latter a moderate insecticidal activity corresponded to Erythrina berteroana Urb. (Fabaceae) and Cissampelos grandifolia Triana & Planch. (Menispermaceae)27. In this study, no species of Piperaceae, specifically Piper genus, was included, although in Peru it is a large genus with 429 species of which 302 endemic 28)(29) and numerous species show a great potential in the production of biocidal chemical compounds. Likewise, worldwide, the Piper genus has been the subject of diverse phytochemical, ecological, and evolutionary studies 30)(31) 32.

In matico (Piper tuberculatum Jacq.), collected in El Cumbil-Chongoyape (Lambayeque), mature spikes (fruits and seeds) of field plants established in university campus (UNPRG-Lambayeque) and in vitro seedlings of 9 to 12 months of culture were studied, under laboratory conditions, on various regional agricultural pests. Aqueous extracts, CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH of mature leaves, stems, and spikes and in vitro plants, with topical application in the mesothorax of III instar larvae of sugarcane borer (Diatraea saccharalis Fabricius), showed that only the extracts CH2Cl2:MeOH and EtOH from mature spikes and CH2Cl2:MeOH extract from in vitro plants reached significant levels of larval mortality33. In fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith), larval mortality by means of contact bioassays was only observed with CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts of mature spikes and CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract from in vitro plants34. In tobacco budworm (Heliothis virescens Fabricius) larvicidal activity was observed when CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extracts from mature spikes were used, reaching a mortality of up to 83.3% and extracts from 12-month-old in vitro plants up to 56.6%35. In cotton stainer bug adulticidal activity was observed when CH2Cl2: MeOH (2:1) extracts from mature spikes were used, causing 91.1 and 97.8% mortality when doses of 0.012 mg/µL were applied in 24 and 48 h of exposure, respectively, while extracts from in vitro plants caused 80% mortality when doses of 0.012 mg/µL were applied in 96 h of exposure36. The potential of in vitro plant cultures in agronomic and forestry species and its insecticidal potential as P. tuberculatum 37)(38) has also been reported.

Additionally, Peru presents a diversity and richness of biomes (16 biomes and 66 sub-biomes) compared to other countries, due to its high geographic and climatic diversity, highlighting the very humid forest on the Atlantic slope, the desert on the Pacific slope, and the humid Páramo near Lake Titicaca39. It is for these reasons that, by using the great biodiversity of higher plants in Peru, such as P. tuberculatum, the objective of the study was to evaluate the ovicidal potential of P. tuberculatum in D. peruvianus, using extracts of mature spikes from field plants and in vitro plants of approximately 12 months old.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Botanical Material

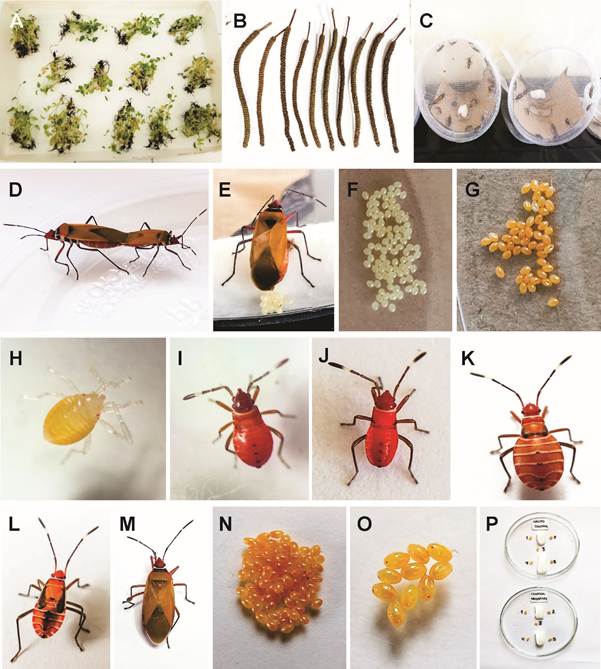

The botanical material consisted of mature spikes (infructescences) and in vitro plants of P. tuberculatum. The mature spikes were collected from adult plants over 15 years old, located in the campus of Universidad Nacional Pedro Ruiz Gallo (UNPRG). The in vitro plants were provided by Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas and Instituto de Biotecnología from the same university. These plants had an average age of 12 months and were grown in vitro conditions (Figure 1A-B). The in vitro plants originated from seeds germinated in vitro and were then propagated by culture of shoot apices and nodal segments in prepared MS culture medium40, supplemented with 2.0% sucrose, vitamins: thiamine, HCl 1.0 mg/L-1 (ICN®, MP Biomedicals Inc., USA) and m-inositol 100 mg/L-1 (SIGMA Cell Culture®, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), the growth regulators 3-indoleacetic acid (IAA) 0.02 mg/L-1 (SIGMA Cell Culture®, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and gibberellic acid (GA3) 0.02 mg/L-1 (SIGMA Cell Culture®, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The pH was adjusted to 5.8±0.1 with HCl or NaOH 0.1 N, before gelation with 0.7% agar (ICN®, MP Biomedicals Inc., USA). This culture medium formulation was used in the micropropagation of numerous Piper species and other species from the Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest (SDTF) of the northern coast of Peru 38)(41) .

2.2 Collecting Insects and Establishing Colonies

The study population consisted of cotton stainer bug adult insects, collected from the upper third of native cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.), and milkweed (Gossypium raimondii Ulbrich) plants, established at the arboretum of Centro de Esparcimiento UNPRG, Lambayeque, Peru. Subsequently, the insects were transported to the laboratory of the Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas UNPRG (Botánica). During the rearing process, in transparent plastic containers of different sizes, hydrophilic cotton soaked in drinking water was used as liquid food, and fragmented native cotton seeds were used as solid food42. Three days after capture, the adults mated, the females laid eggs and the eggs were selected based on their orange color, which served as an indicator of viability. The eggs collected progressed through their biological cycle, reaching the adult stage after 30 days (Figure 1C). These adults mated again, producing new egg batches that were used in the research respective treatments (Figure 1D-O). The sample consisted of 10 viable eggs obtained under in vitro conditions, with 5 replicates per treatment, resulting in a total of 50 eggs per Petri dish.

Figure 1: Biological material used in the study of the ovicidal activity of P. tuberculatum on D. peruvianus: A. 12-month-old in vitro plants subjected to dehydration at room temperature; B. Mature spikes subjected to dehydration at room temperature; C. D. peruvianus under laboratory conditions, after capture in the field; D. Mated specimens; E. Female ovipositing; F. First 24 hours of laying; G. Viable eggs (orange coloration); H. Nymph I; I. Nymph II; J. Nymph III; K. Nymph IV; L. Nymph V; M. Female obtained under laboratory conditions; N. Viable eggs obtained from female specimen obtained under laboratory conditions; O. Experimental unit; P. Method of application of the different doses of the extracts, positive and negative control

2.3 Obtaining Extracts from Mature Spikes and In Vitro Plants of P. tuberculatum

The extracts were obtained with two solvent systems, a mixed one consisting of dichloromethane:methanol (CH2Cl2:MeOH) in a 2:1 ratio, and another simple one consisting only of 96° ethanol (commercial-grade alcohol). Both mature spikes and in vitro plants were dried at room temperature, and then dehydrated in an oven at 40 °C for 5 minutes, before being powdered and subjected to extraction with the aforementioned solvent systems. The extraction process included three consecutive filtrations, each performed at 24-hour intervals. The extracted fractions were then homogenized and placed in Petri dishes to allow solvent evaporation. The resulting extract was recovered with a small spatula, weighed, and stored in amber vials under refrigeration.

2.4 Experimental Treatments

The experimental design was increasing stimulus, with a 4×10×5 factorial arrangement (4 different extracts of P. tuberculatum, 10 different concentrations, and 5 replicates per concentration). The experimental groups (insect pest) were applied different stimuli (extracts at different concentrations). According to the design, the independent variable were the concentrations of P. tuberculatum extracts and the dependent variable was the inhibition of hatching of D. peruvianus eggs.

To carry out the experimental study, following the completion of the pilot tests, 10 treatments per extract were prepared. Eppendorf tubes were used to weigh the different amounts of each extract. Subsequently, it was diluted with 96° ethanol until obtaining 10 µL of final volume, because only 2 µL was used for each repetition. This involved exposing 10 eggs to 2 µL of solution. In the same way, two controls were incorporated, first using 96° ethanol and a second control using Imidacloprid 0.001 mg/2 µL, a widely-used agrochemical known for its insecticidal activity in the field (Table 1). The experimental concentrations were incorporated using a micropipette graduated in microliters and the treated eggs were placed in Petri dishes (Figure 1P).

Table 1: Character experimental concentrations of CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts from mature spikes and in vitro plants of P. tuberculatum on D. peruvianus eggs

| Treatments | Concentration (mg/10 eggs) (mg/2.0 µL) | Volume per repetition (µL) | Volume per Petri dish (µL) |

| Control group | - | - | - |

| Ethanol | 96° | 2.0 | 10 |

| Imidacloprid | 0.001 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 1 | 0.08 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 2 | 0.16 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 3 | 0.24 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 4 | 0.32 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 5 | 0.40 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 6 | 0.48 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 7 | 0.56 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 8 | 0.64 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 9 | 0.72 | 2.0 | 10 |

| 10 | 0.80 | 2.0 | 10 |

10 eggs per repetition, in each Petri dish containing 50 eggs, equivalent to 5 repetitions per Petri dish. Control group: without application of solvents. Ethanol: negative control, and Imidacloprid: positive. 1-10: Experimental concentrations of P. tuberculatum extracts where each concentration had 5 repetitions, evaluated at 6, 12, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours.

2.5 Ovicidal Effectiveness of P. tuberculatum Extracts

The ovicidal effectiveness of P. tuberculatum extracts was determined by the average percentage of inhibition in the hatching of eggs, taking into account the following formula:

% IEH = (ENH/TE) * 100

Where: % IEH, percentage of inhibition in egg hatching; ENH, number of eggs that did not hatch, and TE, total eggs exposed to the different extracts.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

The results obtained regarding the inhibition of hatching of D. peruvianus eggs were processed by the statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Probit analysis43 was performed to determine the LC50 with a significance level of 0.05. The LT50 was determined with Excel software, based on the confidence intervals derived from the Probit analysis.

3. Results

3.1 Inhibition of Egg Hatching

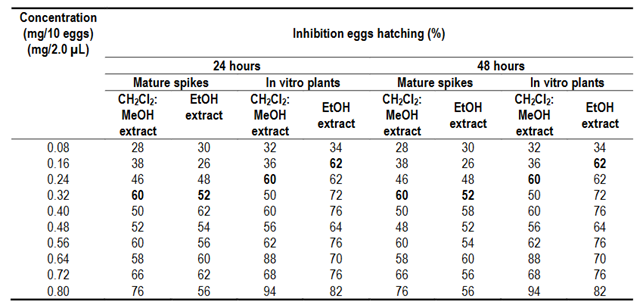

After 24 hours of exposure, in both types of extracts, CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH, egg hatching inhibition increased as the concentration increased from 0.08 mg/2 µL (80 µg/2 µL) to 0.8 mg/2 µL (800 µg/2 µL), with higher inhibition observed when CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts from in vitro plants were used (94% and 82%, respectively) compared to CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts from mature spikes (76% and 56%) (Table 2). After 48 hours of exposure these values remained constant for the in vitro plants, while in mature spikes, only minimal variation was observed.

3.2 Lethal Concentration (LC50) and Lethal Time (LT50)

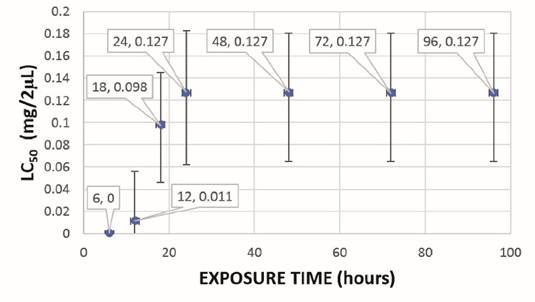

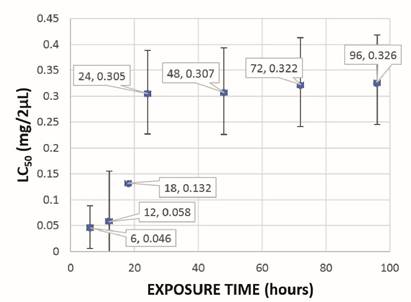

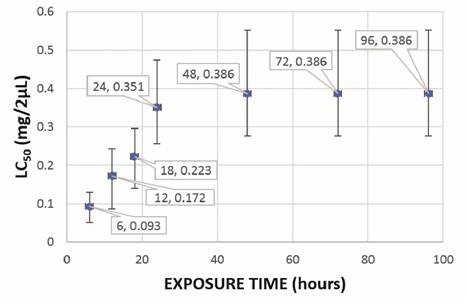

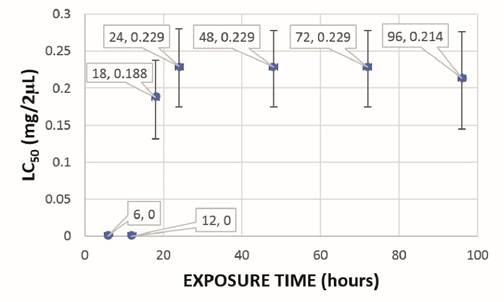

The lethal concentration (LC50) of CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts of mature spikes was 0.305 and 0.351 mg/2 µL, respectively, and in in vitro plants it was 0.229 and 0.127 mg/2 µL, respectively. The lethal time (LT50) of CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts of mature spikes was 24 hours and 18 hours, respectively, with LC50 of 0.305 and 0.326 mg/2 µL for CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract and LC50 of 0.223 and 0.386 mg/2 µL for EtOH extract (Figure 2 and Figure 3). In in vitro plants LT50 was 18 hours, in both types of extracts, with LC50 of 0.188 and 0.214 mg/2 µL for CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract and LC50 of 0.098 and 0.127 mg/2 µL for EtOH extract (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 2: Lethal time (LT50) of the ovicidal activity of the CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract of mature spikes of P. tuberculatum against D. peruvianus

Figure 3: Lethal time (LT50) of the ovicidal activity of the EtOH extract of mature spikes of P. tuberculatum against D. peruvianus

Figure 4: Lethal time (LT50) of the ovicidal activity of the CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract of in vitro plants of P. tuberculatum against D. peruvianus

3.3 Characteristics of Treated Eggs

The in vitro ovicidal activity of P. tuberculatum extracts against D. peruvianus was observed within 24 hours and was characterized by the dark coloration of the eggs, which increased with longer exposure time (Figure 6).

Dark coloration of eggs was observed in both mature spike extracts and in vitro plant extracts of P. tuberculatum and in both types of extracts, CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH. For mature spikes treated with CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract, dark coloration was observed at concentrations of 0.08 to 0.64 mg/2 µL after 72 hours and 0.72 and 0.80 mg/2 µL after 48 hours. For EtOH extract, dark coloration was observed at concentrations between 0.32 and 0.40 mg/2 µL after 72 hours and between 0.48 to 0.80 mg/2 µL from 48 hours. In the case of in vitro plants treated with CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) extract, dark coloration was observed at concentrations of 0.08 and 0.16 mg/2 µL after 72 hours and between 0.24 and 0.80 mg/2 µL from 24 hours. For EtOH extract, dark coloration was observed at concentrations of 0.08 and 0.32 mg/2 µL from 96 hours and 0.40 and 0.80 mg/2 µL after 48 hours.

4. Discussion

Most studies on the antibiosis activity of plant extracts against D. peruvianus were conducted on 4th-instar nymphs and adults. Some of these studies did not report LC50, nor LT50, as is the case of Clusia fluminensis22, with topical treatments (crude hexane extracts of fruits and flowers) dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and applied to 1 µL of each sample, which did not affect the survival of D. peruvianus after 14 days of treatment, possibly because the concentration used was too low; C. hilariana3, with semi-purified fractions (0.005 mg to 0.040 mg) of crude hexane extracts of male stems that affected the development, causing up to 38.9% mortality after 28 days of treatment, with interference in molting and metamorphosis, and body deformations, a similar effect was achieved in this research when the eggs were subjected to the treatments tested, which dehydrated them and deformed them; and Manilkara subsericea23, with a topical treatment (nanoemulsion containing hexane-soluble fraction of fruits) corresponding to 50 μg of extract per insect, which reached a mortality of 44.43% after 30 days; unlike the present study, where these values were reported of extracts from mature spikes and in vitro plants.

With the use of essential oils (EOs) from leaves, interesting results have been obtained when applied against early stages of Dysdercus peruvianus and the Median Lethal Dose-Concentration was established. Complete mortality levels (100%) after one day against 4th-instar nymphs and other effects were achieved with pure EOs of Pilocarpus spicatus20: malformations in insects (similar effect on eggs under the conditions of the present research) and permanent or supernumerary nymphs, the LD50 values were 90 µg/mL for topical treatment and 110.88 µg/cm2 for continuous treatment, both at 22 days of treatment; Perseavenosa21: additionally with a dilution at a concentration of 450 µg/µL the nanoemulsion resulted in 55% of mortality after 20 days, with LD50 values of 24.45 µg/µL and 28.73 µg/µL, respectively; Myrciaria floribunda18: LD50 = 309.64 µg/insect and 93.3%, and after 22 days (LD50 = 94.42 µg/insect) with 0.5 mg/insect, while metamorphosis was poorly affected; Ocotea indecora17: LD50 = 162.18 μg/insect and the same result was expressed on 0.48 mg/insect dilution at 7 days of treatment, and Zanthoxylum caribaeum19: additionally with a 500 µg/insect dilution (LC50 = 215 µg/insect). In all these cases, the high mortality rate (over 90%) of the nymphs is relevant, an effect that has also been achieved in this research (94% mortality) with complete plants from in vitro culture, but at the egg stage with the extract CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) with 0.8 mg/2 µL (800 µg/2 µL) of P. tuberculatum. In this same species, a research36 applied the same type of extract as our research: mature spikes and in vitro plants, but against the adult stage of D. peruvianus, causing 91.1% and 97.8% mortality at doses of 0.012 mg/µL after 24 and 48 h of exposure, respectively; at 96 h of exposure, the extract from mature spikes caused 80% mortality, while in vitro plant extracts caused 80% mortality at the same dose, the LD50 for mature spikes was 0.006 mg/µL and for in vitro plants LD50 was 0.007 mg/µL.

The greater consistency of the egg shell of D. peruvianus, compared to the exoskeleton of the insect in 4th-instar nymphs, may require a higher concentration of the extract and exposure time, considering that the egg shell of the insect, which basically consists of two major parts, vitelline envelope and chorion44, forms a barrier to protect the egg and the embryo from possible adverse environmental influences45. The exoskeleton is composed of a thin, outer protein layer, the epicuticle, and a thick, inner, chitin-protein layer, the procuticle46. A comprehensive review on the insect-egg relationship and their adaptation to different environmental conditions has recently been reported by Jones47.

On the other hand, although oviposition by herbivorous insects is well known to elicit defensive plant responses, there is still an information gap in the mechanism of action in the oviposition-defensive plant responses relationship 48)(49) . In a study on insect species specificity it was observed that treated Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. with eggs extracts and egg-associated secretions of a sawfly (Diprionpini L.), a beetle (Xanthogaleruca luteola Mull.) and a butterfly (Pieris brassicae Linnaeus) caused elicited salicylic acid (SA) accumulation in the plant, and all secretions induced expression of plant genes, such as Pathogenesis-Related (PR) genes50. Similar relationships were studied between larvae of Acrocercops transecta Meyrick (Gracillariidae) and the host plants, Juglans sp. (Juglandaceae) and Lyonia ovalifolia (Wall.) Drude (Ericaceae)51, and populations of Liriomyza trifolii Burgess (Agromyzidae) and Phaseolus vulgaris L. plants52.

In general, in this research, CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts of mature spikes and in vitro plants of P. tuberculatum reached LC50 values between 0.098 and 0.386 μg/2 µL per 10 D. peruvianus eggs tested, with an LT50 between 18 and 24 h of exposure, respectively, which in some cases these values were equal to or lower than those reported for extracts of other plant species and with lower LT50 values.

On the other hand, it has been widely demonstrated that extracts of various plant species, at adequate concentrations, used against insect pests, consistently decreased the total body carbohydrate, protein, and fat levels, which may result in the insects having inadequate nutritional capacity, which will impact all critical actions, inhibiting the hydrolytic enzymatic activity of protease, amylase and lipase, and directly altering the physiological system53. There are several studies on the antibiosis activity of plant extracts against D. peruvianus. In some studies, the effect of secondary metabolites such as the triterpene lanosterol and the benzophenone clusianone, isolated from C. fluminensis, has been clearly demonstrated, which significantly reduced its survival and development22, assuming that terpenes and benzophenones would exert a similar activity with C. hilariana extracts3. In M. subsericea, hexane-soluble fraction from ethanolic crude extract from fruits (HFNE) - blank nanoemulsion and its triterpenes were considered active23. In P. spicatus the insecticidal activity is possibly due to the effect of sabinene (32.27%) and sylvestrene (27.26%) as major constituents of pure EOs20. In P. venosa it was indicated that β-caryophyllene, the major substance present in pure EOs, could be responsible for insect mortality21. Likewise, in M. floribunda it was determined that the monoterpenes were the main compounds found (53.9%), and 1,8-cineole was the major constituent (38.4%) and possibly exerted insecticidal activity18. In O. indecora the sesquiterpene sesquirosefuran was the major compound detected and possibly the one that exerts the greatest insecticidal activity17, and in Z. caribaeum the main constituents, being sylvestrene, muurola-414, 5-trans-diene, isodaucene and α-pinene, significantly increased insect mortality19.

Several secondary metabolites with activity against insects and fungi have been isolated and identified in P. tuberculatum. Four piperamides were identified in leaf and stem extracts: 4,5-dihydropiperlonguminine, piperlonguminine, 4,5-dihydropiperine and piperine, with insecticidal activity against Aedes atropalpus Coquillett54. In seed extract the isobutyl amides pellitorine (compound 1) and 4,5-dihydropiperlonguminine (compound 2) were identified, which showed acute toxicity against Anticarsia gemmatalis Hübner55 and Diatraea saccharalis56. The seeds extracts caused 80% mortality when doses were higher than 800.00 microg insect (1) and compounds 1 and 2 showed 100% mortality at doses of 200 and 700 microg insect (-1), respectively55; similar mortality (82%) was obtained in this research with the EtOH crude extract of plants in vitro against the egg stage. This study demonstrated that the crude extract of P. tuberculatum had potent activity against insects similar to the pure compounds. In this regard, it has been proposed as work strategy the use of heterogeneous extracts of total plant biomass to induce a synergistic effect over some specific organism57.

Additionally, different in vitro strategies have been developed with the aim of increasing the content of secondary metabolites in plants and have even allowed the obtaining of new compounds of great interest in the pharmaceutical industry, fundamentally 58)(59) . This is the case of the production of several insecticidal compounds, namely, pyrethrins, azadirachtin, thiophenes, nicotine, rotenoids, and phytoecdysones60, with the specific example of the production of biopesticide azadirachtin using plant cell and hairy root cultures of Azadirachta indica A. Juss61.

Table 3: Probit analysis components and LC50 values for extracts of mature spikes and in vitro plants of P. tuberculatum on D. peruvianus eggs

In a general way, the LC50 value decreased when the time between application and evaluation increased (Table 3). The data presented confirm that mature spikes and in vitro plants extracts presented potential activities against insects. As already indicated, there are very few studies on the ovicidal activity of plant extracts against insect pests. Ovicidal potential of plant extract mixtures (Azadirachta indica, Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck, Cinnamomun zeylanicum J. Presl, Cymbopogon nardus (L.) Rendle, Derris elliptica (Wall.) Benth. and Millettia pinnata (L.) Pierre) was evaluated against the Asian spongy moth (Lymantria dispar asiatica Vnukovskij), achieving the highest ovicidal activity (97.6% mortality), and this susceptibility to mortality increased with egg maturation62. In another study, the insecticidal, behavioral, biological and biochemical effects of Magnolia grandiflora L., Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi and Salix babylonica L. were evaluated against cotton leafworm Spodoptera littoralis Boisduval, observing that S. terebinthifolius and S. babylonica showed toxic effects, but S. terebinthifolius extract also exhibited high toxicity against S. littoralis eggs (LC50 = 0.94 mg/L)63. Likewise, the effects of numerous plant extracts and essential oils, in particular obtained from species of the Lamiaceae family, on the behavior of Acrobasis advenella Zincken caterpillars and females, the most dangerous pest of black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliot), were evaluated, observing that plant species had a significant influence on the choice of oviposition and feeding site and the type of formulation affected the number of laid eggs64. However, in all these studies, the morphological characteristics of eggs after treatment with plant extracts are not reported.

5. Conclusions

This study has shown that CH2Cl2:MeOH (2:1) and EtOH extracts of in vitro plants of Piper tuberculatum exhibit the best ovicidal activity against Dysdercus peruvianus, with effectiveness between 82-94% at higher concentrations under laboratory conditions. These results indicate that the type of plant material (mature spikes and in vitro plants), type of solvent, and concentration all influence the time of ovicidal effectiveness. Therefore, it is necessary to continue with similar studies on different stages of D. peruvianus, as well as on other pests that affect economically important agricultural crops. Trials should be initiated under laboratory conditions, followed by greenhouse tests, and ultimately field applications. This approach will contribute expressively to agricultural production, food security, and public health.