1. Introduction

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) crop is mainly distributed in tropical climate zones, where it expresses its great growth potential, even under conditions of water deficiency or nutritional limitations. In most of Uruguay the climatic conditions are unfavorable for this crop, therefore, its production is restricted to the northwest zone, the warmest in the country. Sugarcane is planted both in autumn and spring, in fields systemized to allow furrow irrigation during summer. This crop is considered semi perennial, allowing several harvests of the same plantation. In Uruguay the crop stalk harvest is performed manually once a year, in the period from May to October, after burning the senescent leaves to facilitate cutting. The stem of sugarcane is utilized for sugar and ethanol production. The yield of plantations in ALUR, which is the company producing ethanol from sugarcane in Uruguay, is 55 Mg ha-1 in average.

The vigorous growth is accompanied by high nutrient absorption, mainly of N and K, but the crop also uptakes important amounts of P, Ca, Mg, S and micronutrients 1)(2) . The growth and absorption dynamics of nutrients along the year have been described by a sigmoidal curve3. In their work, conducted in Florida (USA), these authors found that after planting, or after cut, comes a period of slow growth and absorption of nutrients (approximately 150 days). This is followed by a period of rapid growth and absorption, which they called GGP (grand growth period), until a plateau is reached approximately at 300 days. While the time lapse for growth or absorption varies in the different production zones, this model is generally accepted to describe growth and nutrient uptake by sugarcane. The nutrient accumulation curve also follows a sigmoidal trend, but precedes that of biomass 1)(4) .

In plantations of Bella Union the fertilization N - K is applied during the fast growth stage, while the phosphate fertilizer is applied generally prior to planting. The dosage of fertilizer is set taking into consideration the results of soil analysis and the expectation of nutrients´ removal by the crop.

At industrial level, the production of ethanol from sugarcane generates many byproducts and waste, which must be managed suitably to avoid negative impacts to the environment5. However, if they are properly handled, they represent an opportunity to transform an environmental liability into a source of nutrients for the crop itself6. Vinasse is one of the byproducts of the fermentation and distillation of juice from sugar cane, generating up to 20 L of stillage per liter of ethanol produced, according to Wilkie and others7. Currently, in ALUR industry in Uruguay about 7 L of vinasse are generated per liter of ethanol. Because it is a liquid residue, vinasse is difficult to handle, and is generally stored in large pools.

Given its potential contribution of nutrients, vinasse can be used for the nutrition of the sugarcane crop, which allows a substantial saving of fertilizers. This residue also contains an organic fraction, which promotes microbial activity when applied to the soil 8)(9) . Although it is accepted that vinasse has become a component of the production system of ethanol from sugar cane as biofertilizer 10)(11) , the application method and timing generally vary from one region to another. In Uruguay, vinasse is applied prior to sowing, and on recently cut crops. This operation is intended to prevent the storage for prolonged periods of large volumes of the effluent. Additionally, the application of vinasse after cutting has the purpose of ensuring the availability of nutrients, especially K, for the regrowth. Because vinasse is supplied early in the season, when irrigation is not required, it is applied directly by aspersion without any dilution.

The management of vinasse as biofertilizer has scarce documented history in Uruguay. Consequently, information regarding its effect on the soil and the crop productivity is limited. An incubation experiment under controlled conditions12 observed that the application of vinasse to the soil in doses of up to 300 m3 ha-1 can make an important contribution of nutrients (N, P, K, Ca, M g, Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn). In coincidence with international bibliography, it was found that the highest nutrient concentration corresponds to K, which is immediately available 13)(14) , while N and P are probably insufficient for the crop requirements. Other macro and micronutrients that are added to the soil with vinasse, but are not normally included in fertilizer recommendations, may contribute to the sustainability of the production system.

Because vinasse application to sugarcane crops is recent in Uruguay, the cumulative effects of this practice have not been investigated. However, long-term studies in other countries have shown positive effects of the application of vinasse on various properties of the soil, as well as on crop productivity 15)(16) . Currently, for soil and cultivation conditions in Uruguay, there is not a reliable set of data to confirm whether the use of vinasse is feasible from the productive and environmental point of view. To assess this question a monitoring program of farms that apply vinasse to sugarcane crops is being conducted. In the framework of this monitoring we evaluated, during the first three years, sugarcane production and extraction of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn in 21 commercial farms receiving vinasse application. To characterize the nutrient use efficiency of the crop, and the proportion of extracted nutrients off site, will contribute to evaluate the long-term sustainability of the production of sugarcane with vinasse irrigation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Study sites

For the purposes of monitoring, 24 sites were selected in 2014, with soils representative of the area planted with sugarcane, in their morphological, chemical, and physical characteristics. The sites were chosen in plantations of commercial production in which vinasse is applied. For the present work we utilized information from the 21 sites that received vinasse during the period 2014-2016 (harvested from 2015 to 2017).

The sites are in a relatively small area, close to the industrial plant (in the range of longitude 57° 31' 13.0'' to 57° 38' 47.2'' W and latitude 30° 17' 34.8'' to 30° 26' 42.4'' S). The climate of this zone is characterized by a mean temperature of the coldest month (June) of 13 °C, while in the warmest month (January) the mean temperature is 25 °C, and the average annual rainfall is 1268 mm distributed over the year, although highly irregular.

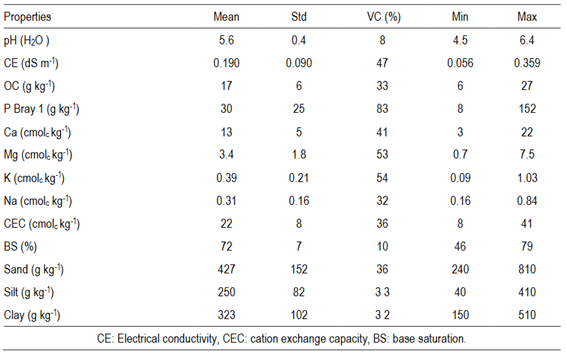

The initial characterization of the soil in each site was taken as a baseline for monitoring. All the selected soils belong to Mollisols and Vertisols. Table 1 presents an overview of the physicochemical characteristics of the A horizon of the soils at the beginning of the study.

2.2 Vinasse irrigation

In the industrial plant, right after the vinasse is generated, it is stored in a large lagoon, from which it is pumped for irrigation. Periodically during the storage, samples are analyzed. According to the information provided by the company, the composition showed variations between years and sampling dates within the year. In the period between 2014 and 2017, on average the pH of vinasse was 4.7 ± 0.1, while the content of N was 479 ± 52 mg L-1, the content of P was 57 ± 19 mg L-1 and that of K was 2269 ± 32 mg L-1.

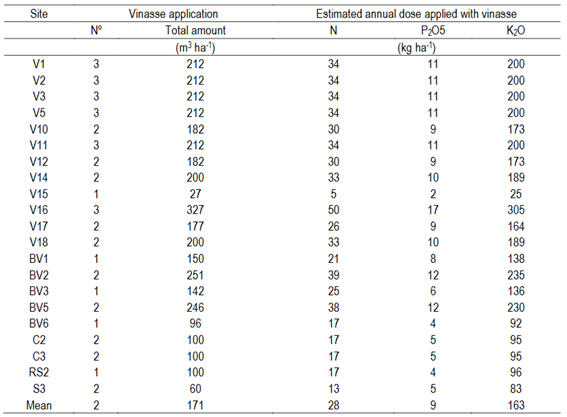

Table 2 presents the number of vinasse applications and the total volume applied in the three studied periods. The acronym identifying sites refers to the location in the study area, but it is desirable to maintain this identification, as it is currently utilized for monitoring of soil properties in the long term.

The survey was made in commercial plantations, hence different strategies of vinasse application were utilized. In consequence, the fields received one, two or three vinasse applications. In all sites vinasse was applied without dilution shortly after harvest, by spreading from a tank.

To estimate the annual dose of nutrients provided by the stillage, its average composition in each growing season was used. Although the composition of vinasse is variable in time, as it is generally for residues and byproducts, we consider that this estimation permits, in general terms, to characterize nutrient application in the different fields. The percentage of N, P and K applied with the stillage respect to the total (sum of the application with vinasse and fertilizers) was in average 15, 63 and 69%, respectively.

2.3 Sampling and plant analysis

The production of sugarcane was evaluated in three growing seasons (2014/15, 2015/16 and 2016/17) in fields receiving vinasse at least once. In 2017 three of the sites (V10, V11 and V12) were not harvested, because excessive rainfall in the area caused flooding of the fields under monitoring.

To quantify the yield and biomass of the crop, prior to the commercial harvest 1 m section was manually harvested from 4 rows, collecting all aboveground biomass. The biomass was weighed in the field, and three plants (stalks with leaves) were taken per 1 m section, in which stalks were separated from the straw (including leaves and sprouts), weighing them separately. Both fractions were cut into small pieces (15 cm). From each fraction (stalk and straw) a subsample was taken, dried in a forced-air-circulating oven at 60 ºC, and ground (< 0.5 mm) for chemical analysis.

In the stalk and straw samples, the total content of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn was determined, calculating the amount extracted in each fraction as the average of the 4 samples per site. The total content of N was determined by a modification of the Kjeldahl method17. To analyze total P the sample was calcinated at 550 ºC, dissolving the ashes with hydrochloric acid (HCl) and determining P content in the extract colorimetrically18. In the same extract the content of Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn was measured by atomic absorption spectrometry, while K and Na were determined by emission spectrometry19.

2.4 Calculations and statistical analysis

Sugarcane yield, in fresh basis (Mg ha-1), was calculated from the proportion of stalk (average of three plants) of each of the 4 subsamples, and their total fresh weight. The content of dry matter (DM) of the subsamples was used to calculate the biomass production, as well as the accumulation of nutrients, multiplying the concentration of each nutrient by the DM amount of the different fractions.

Descriptive statistics was performed (average, standard deviation, maximum and minimum) of sugarcane yield, aboveground biomass, and nutrient (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn) accumulation for the 21 sites. We also examined the relationship of yield and aboveground biomass production with the amount of accumulated nutrients by Pearson correlation analysis.

As an indicator of the efficiency of utilization of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg the amount of nutrients in aboveground biomass per harvested product was calculated, expressed in kg Mg-1, and is interpreted as the higher use efficiency, the lower the index.

3. Results

3.1 Yield and nutrient accumulation by sugarcane crop

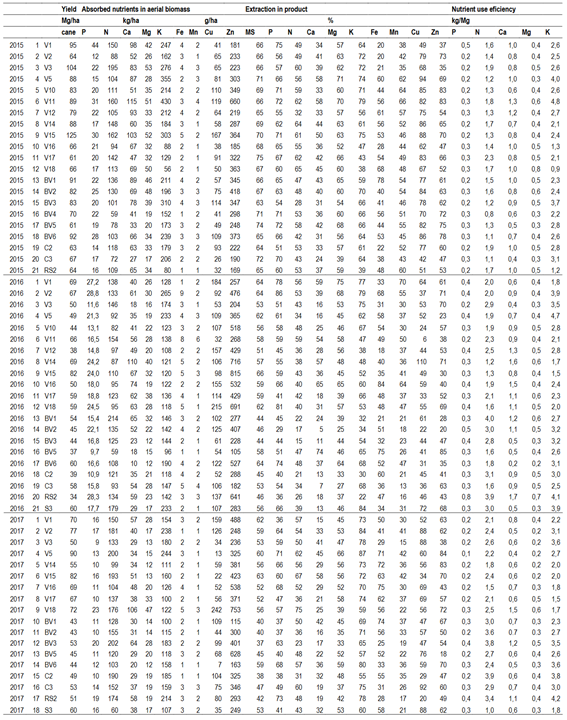

The highest yield of the three growing seasons was obtained in the harvest of 2015 and the lowest in 2016 (Table 3). There was a wide variation in the parameters, both among sites and between years in each site. In general, the 2015 harvest showed greater performance, regarding yield and the absorption of P, K, Ca, and Mg, compared to the other harvests. It was observed that the absorption of micronutrients (Cu, Fe, Mn and Zn) showed a wider range of values compared with macronutrients. Data of nutrient concentration in straw and stalks is presented in the Supplementary material (Table S1).

The different plantations also showed great variability in terms of the efficiency of nutrient use, although the averages of the different harvests were in relatively limited ranges (Table 4).

Although close relationships between yield and biomass production were observed (Table 5), considering all sites and the three years of study, the correlation of growth parameters (yield and biomass) with the amount of macronutrients was generally moderate, while Na and micronutrients´ accumulation showed lower relationships (data not presented). The biomass production was highly correlated to the extraction of N, but sugarcane yield showed greater correlation with the amounts of Mg, Ca, and K. As for the relationship between the absorption of different nutrients, high correlation was observed between the amounts of P, Ca, and Mg accumulated in the biomass.

Table 3: Sugarcane yield and amount of nutrients accumulated in aboveground biomass in three growing seasons. For each period, mean and standard deviation in parenthesis is presented. The last three columns show overall mean, minimum, and maximum for each parameter

| Season | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Mean | Min | Max |

| Nº of sites | 20 | 21 | 18 | |||

| Yield (Mg ha-1) | 80.7 (16.4) | 54.0 (12.5) | 60.1 (14) | 64.7 | 34.4 | 125.3 |

| Biomass (Mg ha-1) | 35.0 (5.1) | 29.1 (5.1) | 34.5 (5.8) | 33.1 | 19.0 | 52.0 |

| N (kg ha-1) | 122 (30) | 120 (34) | 148 (38) | 130 | 59 | 214 |

| P (kg ha-1) | 22 (7) | 19 (6) | 14 (4) | 18 | 9 | 44 |

| K (kg ha-1) | 213 (89) | 150 (43) | 154 (45) | 173 | 56 | 430 |

| Ca (kg ha-1) | 71 (23) | 49 (22) | 43 (18) | 54 | 10 | 115 |

| Mg (kg ha-1) | 37 (11) | 24 (8) | 20 (8) | 27 | 10 | 53 |

| Na (kg ha-1) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | 4 (1) | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| Cu (g ha-1) | 76 (35) | 109 (44) | 79 (54) | 89 | 7 | 242 |

| Fe (kg ha-1) | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Mn (kg ha-1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Zn (g ha-1) | 300 (115) | 411 (189) | 366 (155) | 360 | 105 | 815 |

Table 4: Nutrient utilization efficiency of sugarcane (kg of nutrient in aerial biomass per Mg of stalk). Numbers in parentheses correspond to the standard deviation. The last three columns show overall mean, minimum, and maximum for each parameter

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Mean | Min | Max | |

| N° of sites | 20 | 21 | 18 | |||

| N (kg Mg-1) | 1.51 (0.30) | 2.29 (0.75) | 2.56 (0.75) | 2.11 | 0.99 | 3.97 |

| P (kg Mg-1) | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.36 (0.13) | 0.24 (0.07) | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.82 |

| K (kg Mg-1) | 2.59 (0.88) | 2.95 (0.87) | 2.63 (0.79) | 2.73 | 0.85 | 4.82 |

| Ca (kg Mg-1) | 0.87 (0.20) | 0.90 (0.41) | 0.71 (0.26) | 0.83 | 0.17 | 1.73 |

| Mg (kg Mg-1) | 0.46 (0.12) | 0.44 (0.10) | 0.34 (0.13) | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.76 |

Table 5: Results of the Pearson correlation analysis between yield, aboveground biomass, and accumulation of nutrients in sugarcane (all sites and harvest years). Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.25 corresponds to P <0.05

| Biom. | N | P | K | Ca | Mg | |

| Yield | 0.78 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.64 |

| Biom. | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| N | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.29 | |

| P | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.66 | 0.59 | ||

| K | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.31 | |||

| Ca | 1.00 | 0.83 | ||||

| Mg | 1.00 |

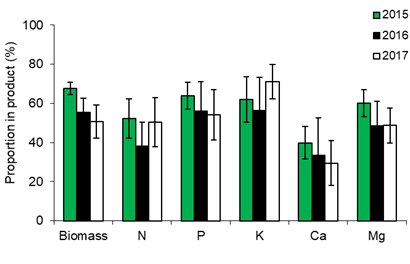

3.2 Exportation of biomass and nutrients

Although most of the aboveground biomass was exported from the site with the stalks of sugarcane, an important amount was not removed with the product. This fraction was in average 13.7 Mg ha-1 of dry matter (range from 6.4 to 26.5 Mg ha-1). This material, mainly composed by senescent leaves, and the apical portion of the plant, represented in average 42% of the total biomass.

The proportion of nutrients accumulated in the aerial biomass that was exported with the commercial product, however, did not always follow biomass patterns (Figure 1). While the exported fraction of K was similar, or even higher than that of the biomass, Ca presented low extraction, remaining in the field about two thirds of the total accumulated amount. Regarding N, approximately half of the accumulated amount was exported with the stalks. Considering all sites and harvests the average nutrient extraction with stalks was 61, 11, 113, 19 and 15 kg ha-1 for N, P, K, Ca, and Mg, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1 Biomass and nutrient accumulation

The area in which sugarcane is planted in Uruguay is characterized by a varied mosaic of soils, attributed to the diverse geological material of the region. While in the area near the Uruguay river the parent material consists of fluvial sediments of different lithology, in more distant areas soils derived from material resulting from alteration of basaltic rocks predominate20. The various parent materials generated soils with important differences in texture and fertility, which frequently present rock fragments and rolling stones in the soil profile. This fact makes the selection of a representative set of soils a difficult task; however, the wide range of properties in the monitoring sites confirms that a substantial part of soil variability was included in this study, where Mollisols and Vertisols are the dominant soils of the area.

The yield of sugarcane fields with application of vinasse was in average higher than the long-term average recorded by ALUR (55 Mg ha-1). This suggests that the vinasse was able to replace partially or totally the supply of nutrients that are usually applied with synthetic fertilizers. The great volume of biomass accumulated each season corroborates that sugarcane has a much higher growth potential, compared to other crops in Uruguay. Due to its physiological characteristics, and because it is produced under irrigation with fertilizer application, sugarcane makes a very efficient use of radiation. Hence it is likely that this factor is important in determining the differences in production between seasons, provided that nutrition and water availability were not limiting factors.

Despite the wide accumulation range of the different nutrients in the aerial biomass, the variability in the annual average was moderate, especially for macronutrients, which gives robustness to the overall mean as representative of their extraction by the crop of sugarcane in this area. Coale and others3 for sugarcane production in Florida, USA (average yield of 103 Mg ha-1), cite extractions of 142, 38, 554, 142 and 68 kg ha-1of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg, respectively. These values, except for the case of N, are above the averages of this work, probably due to higher growth. In coincidence21, comparing different varieties in Pernambuco, Brazil, they obtained significantly higher nutrient extractions than those of our work, for average yields of 195 Mg ha-1. On the other hand, in Alagoas, Brazil2, for four varieties, with average yields of 102 Mg ha-1in first ratoon crops (first regrowth), they cite macronutrient removals in line with those of our work. They obtained an average accumulation in aerial part of 118, 18, 191, 52 and 42 kg ha-1 of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg, respectively.

Da Silva and others2 also examined the removal of micronutrients, reporting total amounts of 46, 3143, 579 and 268 g ha-1 of Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn, respectively, which are lower than the mean values of our study. For plantations in Venezuela1, they found higher micronutrient accumulation, except for Mn, compared to our study (121, 5241, 1142 and 876 g ha-1 of Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn, respectively). It should be noted that the availability and absorption of micronutrients is highly influenced by soil characteristics, such as parental material, texture, and pH. Therefore, it is not expected to find coincidences in their accumulation in plantations from different regions.

In most of the farms, vinasse was the main source of K, which accounts for the greatest quantity among nutrients, and it was the only source in 5 of the fields. The K amounts applied with vinasse were in the range of 25 to 305 kg ha-1of K2O per harvest, exceeding in many cases the amount of K accumulated in the crop's aerial biomass. It has been observed22 that sugarcane makes a very efficient extraction of K from the soil, even beyond its needs (luxury consumption), which can lead to the depletion of the nutrient in the soil without improvements in the yields23. Although luxury consumption of K could have occurred in our study, the amount of this nutrient in aerial biomass showed a high correlation with cane yield, confirming its importance for crop nutrition.

The N content of the vinasse was relatively low, and the amount applied was insufficient for the crop, averaging 28 kg ha-1per year, a quantity lower than that accumulated (average 130 kg ha-1). Moreover, part of the N in the vinasse is in organic form, therefore it should be mineralized to be available for the crop16. In most of the farms, high doses of N fertilizer were applied, resulting in the addition of vinasse accounting for only 15% of the total supply.

The amount of P applied with the vinasse (average 9 kg ha-1of P2O5per harvest) represented a small proportion of the amount accumulated in the biomass. Previous studies 10)(12) 24 showed that a great part of the P from vinasse is readily available to plants, hence it could be absorbed by the crop. Given that a large dose of phosphate fertilizer is usually applied prior to planting, the vinasse contribution for the following re-growth can be significant, even if it were insufficient to replace the P absorbed by the crop. Moreover, it has been observed that the application of vinasse increases soil pH and decreases exchangeable Al in the long term 10)(25) , which enhances the availability of P in acid soils.

4.2 Nutrient use efficiency

Although there are different methodologies to evaluate nutrient use efficiency26, one of the most used indices for sugarcane production is calculated as the amount of nutrients in the crop's aerial biomass per unit of harvested product. A higher value of this index implies a lower efficiency in the use of nutrients, therefore this index allows detecting situations of nutrient deficiency, as well as situations of excessive consumption27. Based on data from different countries (Australia, India, Brazil, South Africa and Hawaii, USA)22, average efficiencies for sugarcane of 1.16, 0.19, 2.00, 0.36 and 0.31 kg Mg-1for N, P, K, Ca, and Mg, respectively, can be cited, which are within the range of this work, although they are lower than the average. In the comparison of four varieties in Brazil2, mean values lower than those of our study were obtained (0.98, 0.17, 1.83, 0.57 and 0.46 kg Mg-1for N, P, K, Ca, and Mg, respectively), suggesting that these crops make a more efficient use of nutrients, probably due to their higher growth potential. In comparison with our results3, higher utilization efficiencies for N and P were obtained (0.76 and 0.22 kg Mg-1, respectively), but lower efficiency in the use of K (3.33 kg Mg-1). On the other hand, in high-yield sugarcane plantations in Pernambuco, Brazil4, utilization efficiencies within the ranges found in our study were reported (between 1.3 and 1.6 kg Mg-1 for N, between 0.21 and 0.28 kg Mg-1 for P, and between 2.4 and 3.2 kg Mg-1for K).

In the 2015 harvest, N and K were more efficiently used than in the other growth periods. This suggests that, in general, the availability of nutrients was not limiting production, although in certain sites this might have occurred. In the case of K, its utilization efficiency was highly variable between sites and between harvests for the same site. The importance of K availability for this crop lies mainly in its role in the metabolism of sugars, and it has been detected as one of its greatest nutritional limitations worldwide 22)(23) . Across fields and seasons one third of the cases presented K efficiency indexes higher than 3.0 kg Mg-1. These high values of the K efficiency index in many of the sites, in comparison with the bibliography, suggest that there was luxury consumption by the crop, although high values of the efficiency index could not be related to large doses of this nutrient, either through the application of stillage or fertilization.

4.3 Nutrient export with product and remaining amount in residues

The large extraction of nutrients with the product (stalks) reaffirms the need of nutrient restoration, not only to achieve higher sugarcane yields, but also to ensure the sustainability of the production system, avoiding depletion of soil nutrients in the long term. It should be noticed that the average N and P extraction with the product was lower than the average amount applied with vinasse, but this byproduct provided a larger amount of K than that exported with stalks. Potassium export represented in average 63% of the accumulated total, resulting higher in comparison with an average biomass extraction of 58%. In contrast, the lowest removal corresponds to Ca, reaching an average of 34%, probably due to the low translocation of this nutrient within the plant. Although the removal of secondary and micronutrients (Ca, Mg, Cu, Fe, Mn, and Zn) showed great variability, and the quantities extracted were relatively small, their removal becomes relevant in the long term. In this context, the application of vinasse constitutes a management practice that ensures sustainability in the replacement of these nutrients, which are not incorporated through fertilization. On the other hand, P and N needs are not likely to be fulfilled through vinasse application, therefore these nutrients should be complemented with fertilizer applications.

The amounts of harvest residues were in the range reported by Digonzelli and others 28) for plantations in Tucumán, Argentina, as well as in Brazil29. The crop residues that remain in the field fulfill various functions. In addition to the recycling of nutrients, they can contribute to the control of erosion, water retention and conservation of soil organic matter 5)(29) 30. Because in Uruguay dry leaves are burned prior to harvest, probably some nutrients suffer losses (mainly N and S), although in our work these losses were not quantified. However, after the harvest it was possible to observe partially burned residues and ash accumulated on the site, representing a reservoir of nutrients for the next production cycle, and offering some protection to the soil surface. On the other hand, in countries where mechanized harvest is carried out, it has been found that residues´ accumulation on the surface can negatively affect regrowth31. This could justify the removal of part of the material for energy production, leaving a lower, and easier to handle, mass on the soil surface32.

Our results suggest that although burning is undesirable from the environmental point of view, its abandonment in the plantations of Uruguay will require technological solutions to manage the large mass of residues left by sugarcane.

5. Conclusions

In view of the high levels of yield, the amounts of nutrients accumulated in the aerial biomass of the crop, and the large proportion exported from the site with the stalks, it is concluded that the supply of nutrients from the vinasse will contribute to the sustainability of the production system. In parallel, the use of this byproduct will enable saving important amounts of fertilizers (NPK), avoiding potential environmental hazards due to industrial residues mismanagement.