Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Odontoestomatología

versión impresa ISSN 0797-0374versión On-line ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.27 no.45 Montevideo 2025 Epub 01-Jun-2025

https://doi.org/10.22592/ode2025n45e237

Investigation

Bioethical tension in the practice of the dental clinic during undergraduate training at the National University of Córdoba

1PhD en Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Odontología. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Córdoba, Argentina. lisucor@gmail.com.ar

2Lic. en Psicología Facultad de Odontología. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Córdoba, Argentina.

3PhD. en Odontología, Facultad de Odontología. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Córdoba, Argentina.

Objective:

recognize the implications of bioethical conflicts that arise in dental clinic practice during undergraduate training.

Methodology:

From a qualitative approach, we investigated experiences lived by students, during the training path of dental clinical practice, in which bioethical conflicts or dilemmas have arisen. Students from the professional cycle of the dentistry degree at the National University of Córdoba participated, and in-depth interviews were carried out. The constant comparative method was applied to build theory on the bioethical dynamics implicit in dental clinical practices during undergraduate training.

Results:

during clinical practice, students face situations of ethical implication, with little theoretical and methodological mastery, so they are resolved by chance or by prioritizing academic demands.

Conclusions:

It is necessary to strengthen the comprehensive training of dentists, including analysis and reflection from a bioethical perspective.

Keywords: dental education; professional ethics; dental ethics

Objetivo:

Reconocer las implicancias de conflictos bioéticos que se presentan en la práctica de la clínica odontológica durante la formación de grado.

Metodología:

Desde un abordaje cualitativo se indaga sobre experiencias vivenciadas por estudiantes, durante el trayecto formativo de la práctica clínica odontológica, en las que se hayan planteado conflictos o dilemas bioéticos. Participaron estudiantes, del ciclo profesional de la carrera de odontología de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, y se realizaron entrevistas en profundidad. Se aplicó el método comparativo constante, para construir teoría sobre la dinámica bioética implícita en las prácticas clínicas odontológicas durante la formación de grado.

Resultados:

Los estudiantes durante la práctica clínica enfrentan situaciones de implicancia ética, con escaso dominio teórico y metodológico, por lo que las mismas se resuelven de manera fortuita o priorizando la exigencia académica.

Conclusiones:

Es necesario fortalecer la formación integral de los odontólogos, incluyendo el análisis y la reflexión desde la perspectiva bioética.

Palabras claves: educación en odontología; ética profesional; ética odontológica

Objetivo:

reconhecer as implicações dos conflitos bioéticos que surgem na prática clínica odontológica durante a graduação.

Metodologia:

A partir de uma abordagem qualitativa, investigamos experiências vivenciadas por estudantes, durante o percurso formativo da clínica odontológica, nas quais surgiram conflitos ou dilemas bioéticos. Participaram estudantes do ciclo profissional da carreira odontológica da Universidade Nacional de Córdoba, foram realizadas entrevistas em profundidade. O método comparativo constante foi aplicado para construir teoria sobre a dinâmica bioética implícita nas práticas clínicas odontológicas durante a graduação.

Resultados:

durante a prática clínica, os estudantes enfrentam situações de implicação ética, com pouco domínio teórico e metodológico, sendo resolvidas por acaso ou pela priorização de demandas acadêmicas.

Conclusões:

É necessário fortalecer a formação integral dos médicos dentistas, incluindo análise e reflexão numa perspectiva bioética.

Palavras chaves: educação odontológica; ética profissional; ética odontológica

Introduction

Dental tradition has promoted professional training with a procedural approach centered on tooth morphology to restore and recover its functionality.

Today, scientific and technological advancementsr foster new therapeutic strategy options. In this context of diverse clinical approaches, bioethical analysis and reflection are essential for clinical practice grounded in values linked to human rights. These values guide strategies to appropriately address bioethical dilemmas and/or conflicts that may arise during patient care 1. All possible recommendations and procedures for dental treatments have an ethical foundation and consequences 2.

As a professional, the dentist must address social needs and demands, requiring not only knowledge and know-how-that is, a qualified praxis supported by theory-but also a "knowing how to be" in professional practice 3. Formal ethical analysis and reflection are essential components of decision-making for health professionals. They face value conflicts in all their recommendations, procedures, and treatments, where the final decision will impact the well-being of their patients, making it a moral choice (4.

In this regard, dentists' first moral duty is to do good for their patients, specifically in the oral component of health. However, this "good" may not be the same for the dentist and the patient, a discrepancy that can result in dissatisfaction from either party.

Currently, changes in public policy and scientific and technological development promote new therapeutic strategies. The interrelation between intra-individual and inter-individual causality, including myths and beliefs, leads dentists to think not only about the specific treatment of a lesion but also about actions that bring substantial changes to people's quality of life while respecting their beliefs-in other words, accompanying the processes of integration of self-eco-organization (4. In this new scenario, dental professionals are compelled to abandon their paternalistic and prescriptive role, where they applied the best-known technology and bioethical conflicts were minimal due to the limited availability of alternatives. The emergence of a wide range of therapeutic options forces dentists, when they lack mastery of certain techniques, to refer their patients to other specialists. Bioethical analysis and reflection become essential in a professional practice that fosters a value-based clinical approach involving all health personnel and guiding strategies to appropriately address the bioethical conflicts that may arise during the patient care process.

Under this paradigm, the patient's right to responsibly choose their dental treatment and respect for their autonomy over their body, particularly their health, come into tension within the dentist-patient relationship. The right to information emerges as a concrete manifestation of the right to health protection, which, in turn, is one of the fundamental rights of the human person (5. Currently, what is expressed in a formal administrative act is synthesized into the informed consent document-an instrument that often loses sight of its intended purpose in practice.

When referring to ethics in dentistry, we invoke the implicit moral responsibility in praxis and the competence in performance as indispensable requirements for adhering to bioethical principles (3.

At the National University of Córdoba (UNC), the Dentistry Degree incorporates a process of patient care in clinical classrooms equipped with basic technology, where students treat patients of varying ages and socioeconomic contexts. This allows them to confront a range of oral health problems, enriching their practical experience and developing diagnostic and treatment skills. Clinical practices take place in a controlled environment where students handle patients of varying complexity, applying theoretical knowledge to practical situations under the supervision of a professional dental instructor- ensuring the quality of care and compliance with bioethical and biosafety standards.

In light of the above, and with the aim of promoting the human dimension alongside the scientific and technical aspects of the curriculum in institutions training oral health professionals, as proposed by Lafaurie M et al. 6, our general objective is to identify, from the students' perspective, the bioethical principles implicit in clinical practices during

undergraduate dental training. To achieve this, we have established the following specific objectives:

To know the experiences of final-year dental students regarding bioethical issues encountered during clinical practice.

To analyze the bioethical principles in tension during clinical practice.

To identify both explicit and implicit instances of ethical education within the dentistry program curriculum.

To characterize the teacher-patient-student model of interaction.

Methodology

From an epistemological perspective within the framework of the hermeneutic-interpretive paradigm based on symbolic interactionism, a qualitative study was conducted following the regulations of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) (7, which establish guidelines for applying the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964 and amended in 1975, 1983, and 1989 8. The work protocol was approved by the Municipal Clinical Bioethics Network of the Municipality of Córdoba. To carry out the study, final-year dentistry students in 2019 were publicly invited to participate during classes of the subjects Operative II A, Pediatric Dentistry B, and Preventive and Community Dentistry II, all part of the clinical/professional cycle of the Degree, with workloads of 160, 160, and 120 hours, respectively. The study population included a total of 150 students. Those interested in participating provided their email addresses to receive more information about the research and their role in it. The study group consisted of students who gave their informed consent and assent to participate in the research. To collect data, the scripted interview technique was applied9, following guidelines derived from the research objectives. The dimensions considered were: Sociodemographic profile; Background in specific knowledge; Experience with ethical problems encountered during clinical practice; Autonomy (discursive or real); Benevolence; Communication (relational model); Justice (inequality/equity); Treatment selection criteria; and iatrogenesis (own responsibility, responsibility of another professional, or responsibility of the patient).

Forty-eight recorded interviews were conducted, with the prior consent of the participants, at a single point in time for each, lasting approximately 45 minutes. These interviews were subsequently transcribed into written text for analysis 10. Three operators, who were previously trained and familiarized with the study's objectives, carried out the interviews.

For the analysis of the texts, the guidelines of Grounded Theory by Glaser and Strauss11 were followed. Within this framework, theoretical sampling was performed, and the Constant Comparative Method was applied10. This approach generated descriptive, integrative descriptive, and interpretative categories regarding the dynamics of bioethical principles implicit in various dental clinical practices during undergraduate training. The analysis phase was carried out by the authors, initially working individually and then collaboratively, allowing the same situation to be reviewed by more than one person, thus ensuring researcher triangulation.

The process began with reading the material, followed by selecting fragments, generating codes, and subsequently constructing emerging categories with their properties. This approach enabled an understanding of the reality experienced by dental students during their clinical practices, from their own perspective.

Results

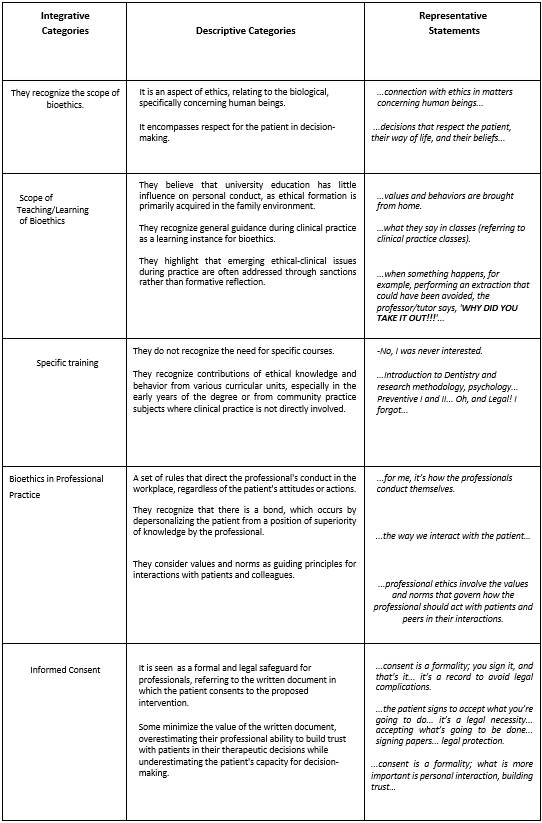

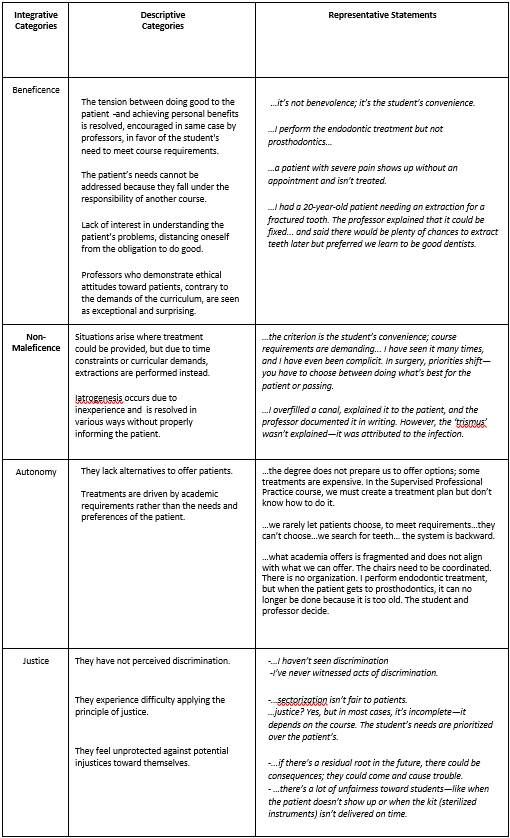

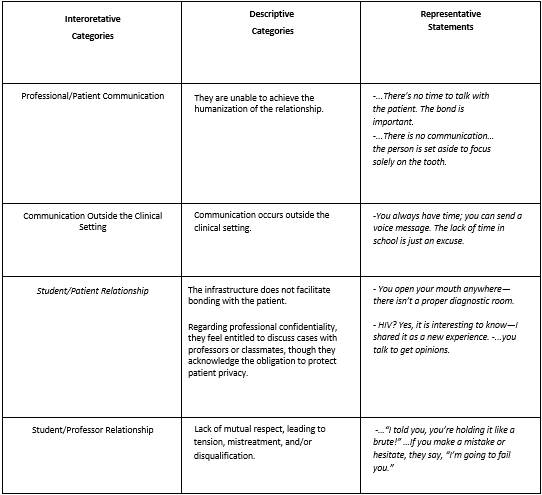

During the analysis of the primary data obtained from interviews with dental students, a series of emerging categories were identified and grouped into two main dimensions: Bioethics training and Ethical dilemmas arising in the clinical practice of the Degree. Regarding the background in specific knowledge, various descriptive categories were recognized and could be grouped into interpretative categories, as shown in Table 1. The interviewed students, through their statements, revealed ethical dilemmas inherent to the learning context of clinical practice. These dilemmas were grouped into integrative categories that largely align with the bioethical principles proposed by Beauchamp TL and Childress JF 12 (Tables 2 and 3).

Analysis and discussion

The professional profile of dentists requires advanced specialized training, direct interaction with individuals in daily practice, and a social responsibility to promote community well-being. In the dynamics of this practice, they face situations that cannot be resolved solely by applying scientific knowledge. Instead, professionals must broaden their reflections, recognizing that different therapeutic alternatives involve bioethical considerations, as these decisions directly impact patients' well-being.

Our interviewees noted that values are largely brought from home. While it is true that ethical values are developed within the family and later shaped through social interactions under the influence of formal education, traditions, idiosyncrasy, and beliefs (3, they are insufficient to address the bioethical conflicts that arise in clinical situations. Today, the home-understood as family-exists in continuous interaction with a society that is constantly changing and being shaped through clinical practice, peer relationships, and the use of technological communication means such as computer networks, among others.

The family, as a permeable membrane, is not solely responsible for the acquisition of values but serves as a filter, fostering and guiding the development of critical thinking for the adoption or rejection of those values.

Bioethics focus on legitimizing decisions through dialogue and participation, as these are "a moral manifestation, an act of public adherence to a set of values" 13. University education offers an invaluable opportunity for supplementation and reinforcement to achieve higher levels of moral development, which can be embodied in models of bioethical conduct, both personally and professionally14. Roman 13) states that it is during university life that individuals can reach a development that enables bioethical reflection.

Supporting the idea that university training in bioethics is essential to educate competent professionals-knowing how to know, how to do, and how to be with others-two fundamental questions arise: what to teach and how to teach. Various authors 13 agree, with different nuances, on an ideal model in which bioethical content should be addressed transversally throughout the degree and reinforced at the end with a dedicated space for professional ethics or deontology. The current curricular proposal of the Faculty of Dentistry at the UNC, where the interviewees are enrolled, aligns with this model. Regarding this, the interviewed students point out that bioethics content is offered in various subjects, but not systematically. While some subjects do include spaces for bioethical content, these are seen by both teachers and students as secondary, with little relevance and not tailored to the specificity of the discipline. This overlooks the fact that therapeutic decisions are influenced by the bioethical dimension. In other cases, bioethical concepts do not appear in the curricular content of the subject and are left to the discretion of the teacher, as evidenced by the fact that students refer indiscriminately to different subjects, especially in the introductory and basic cycles. Regarding the curricular space dedicated specifically to bioethics content, the current curriculum of the Faculty of Dentistry at the UNC includes the subject Legal Dentistry. The contents of this subject are organized into four main blocks: Legal Dentistry Contents; Auditing and Economics Contents; Forensic Dentistry Contents. The legal dentistry segment is developed in 4 units, with Unit II entitled: Ethics. Deontology. Bioethics, aimed at teaching concepts related to conduct, norms, duties, and the social responsibility of the professional. Students who have taken or are taking the subject Legal Dentistry mention it alongside other subjects, without emphasizing its specificity in bioethics.

Furthermore, regarding informed consent, students show confusion between inherent principles of rights to be safeguarded or respected and the legal instrument for their protection.

Likewise, they struggle to identify moral or bioethical values, often viewing them through personal preconceptions, believing they are not influenced by their own or the patient's values; overlooking the fact that practice inherently involves a particular way of perceiving and treating patients, shaped by the assumed clinical model.

Interviewees express that when ethical-clinical problems arise in the practices, they are used for sanction and not for formative reflection on what happened. This evidences the limited valuation of the bioethical dimension for professional training. When faced with the problem, as shown by the teacher's expression, WHY DID YOU TAKE IT OUT!!!..., (Table 1), work is done from a pedagogical model of censorship instead of metacognition and critical reflection on the response that arose in the face of the problem. Thus, the opportunity for meaningful learning of the ethical implications of the situation based on reflection on one's own practice is lost.

Regarding how to teach Bioethics, it is important to consider Diego Gracia's 14 deliberation method for resolving bioethical conflicts. This method is based on three main phases:

Factual analysis: Describe the situation in detail, identifying the actors involved and the relevant circumstances.

Values analysis: Examine the values and ethical principles at stake, considering the perspectives of all parties involved.

Deliberation and decision-making: Evaluate the possible alternatives for action, weighing the pros and cons of each to reach a decision that is ethical and justified.

The implementation of Diego Gracia's 14 deliberation method in the training of health professionals can be carried out through several strategies: Integration into the curriculum, including specific bioethics courses that address the deliberation method, allowing students to become familiar with its phases and apply them in practical cases; Applying participatory teaching strategies such as PBL (Problem-Based Learning) and case studies, which are suitable methods for preparing students to analyze bioethical conflicts and make decisions. These strategies enable a comprehensive approach and promote learning through dialogue and reflection. By using real or hypothetical clinical cases, students can practice the analysis of facts, values, and deliberation, fostering critical thinking and ethical decision-making. Simulations and role-playing of clinical situations where students assume different roles (patient, physician, family member) allow them to approach ethical conflicts from different perspectives.

The goal is not to train experts in bioethics but to integrate bioethical content into the curriculum's various subjects, recognizing bioethics as a longitudinal discipline that provides essential tools for decision-making in future professional practice, considering specific contexts 15.

In the teaching and learning process, professors play a critical role, serving as models for students both at a scientific-technical level and in their professional conduct. Professors bring their own moral perspectives to their teaching, and it is inevitable that they perform their educational role based on professional ethics. Thus, the teacher’s behavior will positively or negatively influence the students (16. In this regard, the training institution should establish its own bioethical code to guide both teaching and student practices during the clinical training stage, ensuring these practices are not left to the teacher's discretion alone. One approach recommended by various authors17 is to provide training for teachers in bioethics as a way to strengthen their teaching role and address the hidden curriculum. This strategy has been successfully implemented at other universities.

In the course of providing dental care in the university clinic, a triad-or quartet-is formed, consisting of teacher, patient, and student. This dynamic creates a dilemma regarding the hierarchy of interests among the different actors. For educational purposes, the focus often shifts away from the patient’s needs to prioritize the training and evaluation of the teacher and student.

The trend toward specialization is reflected in the segmentation of the curriculum. As a result, students are limited to performing only the specific procedures within their specialty subject (e.g., Surgery, Endodontics, Periodontics). Treatment alternatives are restricted to those defined by the curriculum, which do not always fully address the patient’s needs. This limitation eliminates opportunities to initiate clinical reasoning processes centered on the individual and their health problem.

Adding to these challenges is the conflict between academic timelines (term, semester, week, month) and the timeline of patient care. Students are unable to extend their care beyond the allotted time dictated by academic evaluation requirements. In this context, it is suggested to invert the logic of training and evaluation, prioritizing the patient's care needs and their resolution. This approach would evaluate the student’s execution and progress on their expertise while incorporating the patient’s voice.

In clinical dyadic interventions, responsibility and commitment always fall on the operator, regardless of the assistant’s level of knowledge or technical skills. This dynamic fosters competition and threatens the balance between peers.

This contextual conditioning is what students refer to when they point out that the faculty does not facilitate the application of bioethical principles. Students recognize the difficulty of resolving intervention problems, as choosing any of the possible solutions inherently involves bias. Furthermore, in this clinical practice learning context, problems are analyzed predominantly from a technical perspective, overlooking the suffering subject, their history, and life trajectory. Neglecting these aspects denies the opportunity to consider better alternatives tailored to each individual’s socio-historical and cultural circumstances. In other words, technical aspects are considered over co-managed therapeutic projects, which would be the ideal approach 18. In today’s society, interpersonal relationships have become crucial for achieving productive efficiency and improving the quality of life in communities (19, 20), to such an extent that beings can no longer meet their needs as isolated individuals.

Within various relational contexts, whether in public, private, or independent services, different factors will always influence the prioritization of bioethical principles according to the patient’s comprehensive needs.

As previously mentioned, prioritizing the well-being of the suffering subject is essential in clinical care. Understanding that "the good" may be interpreted differently by various actors transforms clinical care from merely applying academic knowledge into an intersubjective process 21.

Dialogue enhances communication and enables shared decision-making that benefits the health situation. Within the field of health professionals, this transformation is often met with resistance-some practitioners do not align with current complexity paradigms, which emphasize interdisciplinary practice within the framework of a broadened and extended clinical model; one that is centered on the subject, promoting a horizontal patient-professional relationship, with the establishment of patient autonomy being fundamental to therapeutic success. The principle of autonomy is the expression of the acknowledgment that those affected by clinical dental actions are not incapable of deciding about their own well-being. On the contrary, they are autonomous individuals who must be consulted to obtain their consent for therapeutic decisions.

Recognizing autonomy as an inherent attribute of human beings not only ensures better outcomes in the therapeutic process and reduces patient-professional asymmetry but also promotes the democratization of knowledge. Like other bioethical principles, the principle of autonomy serves as a guiding framework. It is essential that these principles are grounded in the concept of the person, acknowledging them as a valid interlocutor to understand their intersubjective value.

In a technocratic clinical model, professionals, driven by their intention to benefit their patients, often adopt a paternalistic attitude, acting based on what they believe is best for the patient's health. Worse still, in many cases, actions are taken without patients being adequately informed or fully aware of the procedures being performed on them. In both cases, the attitude contradicts the application of bioethical principles that should guide clinical care. First, the principle of beneficence is neglected, as "good" is addressed solely from the professional's perspective. Autonomy is also impeded, as the patient cannot make informed decisions due to a lack of adequate information. Furthermore, when the professional views the patient exclusively through his or her own subjectivity, without considering the patient’s emotional and socioeconomic context, it becomes impossible to provide care that aligns with the patient’s possibilities and potential. In a society like ours, marked by limited economic resources and diverse needs, it is essential to adopt criteria that ensure clinical outcomes are both relevant and appropriate to the socioeconomic and cultural reality. As Cortina 22 states, the mentioned principles serve as guides for addressing bioethical issues, but only when they are philosophically grounded in the concept of the person as a valid interlocutor, capable of fully interpreting their intersubjective validity.

Additionally, when these principles come into tension, joint reflection with the patient is necessary, leaving the final decision in the hands of the affected individual. This once again highlights the importance of dialogue with the patient-not as a matter of empathy, but as a process of mutual respect and collaborative decision-making.

The student's clinical practice training provides the opportunity to offer comprehensive professional education that integrates both scientific-technical education and bioethical education, which includes the intersubjective relationship with the patient. .

The extended clinic model (21, centered on the subject, reclaims the significance of the bond as a therapeutic tool, where the patient is an active actor/subject in the collaborative construction of a therapeutic plan. This approach facilitates overcoming the fragmentation between the biological, the subjective, and the social. It acknowledges patients as valid interlocutors, and incorporates bioethical principles into practice in all relevant aspects. Integrating the extended clinic model into undergraduate training would promote a professional practice grounded in ethical values. We align with Sousa Campos (21 in that including curriculum objectives to promote the progressive development of autonomy for patients and communities is essential. This would require professionals who are open to reevaluating their knowledge and practices by integrating biological, subjective-psychological, and evaluative-social dimensions.

Conclusions

It is necessary to strengthen the comprehensive training of dentists, including analysis and reflection from a bioethical perspective. Our work has allowed us to understand the perception of bioethical issues that arise during clinical practice among students who were in their final year of dentistry in 2019.

- Students' statements highlight the tension between bioethical principles and the educational practices they experience during their undergraduate training.

- The information emerging from the analysis of the interviews reveals both explicit and implicit instances of bioethical training within the dental curriculum, which influence decision-making during clinical practice. From the interviewees' perspective, the institution does not foster the application of bioethical principles.

- A paternalistic model of teacher-patient-student relationship is identified from the participants' statements.

- Emerging bioethical conflicts during clinical practice are not used as opportunities for reflective dialogue on the application of bioethical principles in decision-making.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dentist Agustín Ponce and Biologist Natalia Agüero for their selfless collaboration in implementing the information collection techniques.

REFERENCES

1 - Suárez-Ponce D, Watanabe-Velásquez R, Zambrano-De la Peña S, Anglas-Machacuay A, Romero-Álvarez V, Montano-Rubín De Celis Y. Bioética, principios y dilemas éticos en Odontología. Odontol. Sanmarquina 2016; 19(2):33-40 [ Links ]

2 -Torres-Quintana María Angélica, Romo O Fernando. Bioética y ejercicio profesional de la Odontología. Acta bioeth. 2006 12(1): 65-74. Disponible en: http:// www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1726-569X2006000100010&lng=es. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S1726-569X2006000100010. [ Links ]

3 - Orellana Centeno J E, Guerrero Sotelo R N. "Bioética desde la perspectiva odontológica" Revista ADM 2019: 76 (5): 282-286. [ Links ]

4 - Izzeddin-Abou Roba, Jiménez Francis. Bioética en Odontología, una visión con principios. CES odontol. 2013. 14; 26(1): 68-76. Disponible: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php? script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-971X2013000100007&lng=en. [ Links ]

5 - Botazzo C. "El nacimiento de la Odontología. Una arqueología del arte dental". Buenos Aires. Lugar Editorial:2010, 208p [ Links ]

6 - Lafaurie M, Perdomo A, Tocora J, González M, Amaya M, Barbosa R, Castelblanco M, Garzón J, Hincapié S, Huertas L, Ochoa M, Restrepo L, Triana L "La humanización en salud: reflexiones de docentes, estudiantes y personal administrativo" Rev. salud. bosque. 2018; 8 (2): 83-10 [ Links ]

7 - Organización Panamericana de la Salud y Consejo de Organizaciones Internacionales de las Ciencias Médica. Pautas éticas internacionales para la investigación relacionada con la salud con seres humanos, Cuarta Edición. Ginebra: Consejo de Organizaciones Internacionales de las Ciencias Médicas (CIOMS); 2016. Disponible en: https://cioms.ch/ wp-content/uploads/2017/12/CIOMS-EthicalGuideline_SP_INTERIOR-FINAL [ Links ]

8 - World Medical Association. World Medical Association "Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects". JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053 .Disponible en : https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/ fullarticle/1760318 [ Links ]

9 - Maxwell JA."Qualitative research design. An interactive approach." 3º ed California SAGE Publications, Inc. 2013. 218p [ Links ]

10 - Sampieri R. "Metodología de la investigación" (5ta ed.). McGraw-Hill, 2012. 656p 17 [ Links ]

11 - Glasser B, Strauss A. "The Discovery of Grounded Theory: strategies for Qualitative Research". Chicago: Aldine. 1967. Strauss A, Corbin J. Grunded Theory Research: Procedures, Canonsm and Evaluative Criteria". Rev Qualitative Sociology. 1990. 13 (1):3-21. Disponible en: https://link.springer.com/journal/11133/volumes-and-issues/13-1 [ Links ]

12 - Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. "Principios de Ética Biomédica", Barcelona:Masson. 1999 [ Links ]

13 - Román B. "Apuntes para una ética del profesor universitario". Ars Brevis 2001: 355-376 [ Links ]

14 -Gracia D. Fundamentación y enseñanza de la bioética. Bogotá. 3ra Edición. Editorial 2021. 240p [ Links ]

15 - Justen M P, Schneider F, Warmling, C M." Decisão diante de conflitos bioéticos e formação em odontologia" Revista Bioética,2021: 29 (2): 334-343 Conselho Federal de Medicina, Disponible en : https://www.scielo.br/j/bioet/a/tB7dxm6LzGdw7f5M7FZNkkD/? lang=pt [ Links ]

16 - López V F, Ariasgago O L, Ojeda de Gómez M C "La formación moral en la enseñanza superior en ciencias de la salud" Acta Odont. Venez. 2016, 54 (2). Disponible en https:// repositorio.unne.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/123456789/52315/RIUNNE_FODO_AR_Lopez Ariasgago-OjedadeGomez.pdf [ Links ]

17 - Zaror Sánchez C, Muñoz Millán P, Espinoza Espinoza G. Vergara González C, Valdés García P. "Enseñanza de la bioética en el currículo de las carreras de odontología desde la perspectiva de los estudiantes". Acta Bioethica. 2014:20 (1):135-142 [ Links ]

18 - Gastão Wagner de Sousa Campos "Gestión en salud: en defensa de la vida" /. - 1a ed. - Remedios de Escalada: De la UNLa -Universidad Nacional de Lanús, 2021. Libro digital, PDF - (Cuadernos del ISCo / Salud Colectiva; 14) (Consultado 20 /3/ 2021) Disponible http:// isco.unla.edu.ar/edunla/cuadernos/catalog/view/15/26/63-1 [ Links ]

19 - Iñiguez G, Tagüeña Martínez J, Kaski KK, Barrio RA. "Are Opinions Based on Science: Modelling Social Response to Scientific Facts". PLoS ONE. 2012:7(8):421-22. [ Links ]

20 -Unger F."Health is wealth: considerations to european healthcare".Prilozi. 2012:33(1):9-14. [ Links ]

21 -Gastao Wagner de Sousa Campos "Saúde Paidéia". São Paulo: Editora Hucitec; 2003.185p [ Links ]

22 - Cortina A. Ética aplicada y democracia radical, Tecnos, Madrid, 1993, parte III: "Los retos de la ética aplicada". pp. 183-192 [ Links ]

Data availability The dataset supporting the results of this study can be requested at lisucor@gmail.com.

Ethics Committee The work protocol was approved by the Municipal Clinical Bioethics Network of the Municipality of Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina

Authorship Contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): / 1. Project Administration 2. Funding Acquisition 3. Formal Analysis 4. Conceptualization 5. Data Curation 6. Writing - Review and Editing 7. Research 8. Methodology 9. Resources 10. Writing - Original Draft Preparation 11. Software 12. Supervision 13. Validation 14. Visualization. L.S.C. 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14. I.A.M. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14. P.C.G. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14. M.B. 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14.

Received: May 17, 2024; Accepted: October 23, 2024

texto en

texto en