Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Odontoestomatología

versión impresa ISSN 0797-0374versión On-line ISSN 1688-9339

Odontoestomatología vol.23 no.37 Montevideo 2021 Epub 30-Abr-2021

https://doi.org/10.22592/ode2021n37a1

Research

Psychosocial impact of periodontal disease on the quality of life of patients of the school of dentistry (Udelar). A qualitative-quantitative study

1 Departamento Periodoncia. Facultad de Odontología, Universidad Católica del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay aaricetaodontologa@gmail.com

2 Cátedra de Periodoncia. Facultad de Odontología. Universidad de la República, Uruguay

3 Instituto de Psicología de la Salud, Facultad de Psicología Universidad de la República, Uruguay

Objectives:

To identify the psychosocial factors of periodontal disease and their impact on the quality of life of patients.

Methods:

A mixed quantitative and qualitative study was conducted at the School of Dentistry, UdelaR. The instruments used were a semi-structured interview based on grounded theory and the application of the OHIP-14 (Oral Health Impact Profile) questionnaire that measures the degree of impairment of quality of life (Locker’s theoretical model).

Results:

This population’s psychosocial factors are identified, as well as the emotional and social effects of periodontal disease diagnosis. The results show a 1.46 impact on people’s quality of life on a scale of 0-4, where 4 is the maximum impact. Women showed a higher level of impairment in quality of life (1.54) than men (1.36). The higher the educational level, the more the quality of life is affected.

Conclusions

The limitations of the biomedical approach to dental patient care and the need for a comprehensive approach in periodontal disease patients are clear. Dental professionals need a biopsychosocial care approach given the complexity of periodontal disease.

Keywords: quality of life; periodontal diseases; biopsychosocial impact

Objetivos:

Identificar los aspectos psicosociales de la enfermedad periodontal y su incidencia en la calidad de vida de las personas que la padecen.

Métodos:

Se realizó un estudio mixto cuanti-cualitativo en pacientes de la facultad de odontología UdelaR. Los instrumentos utilizados fueron: entrevista (semiestructurada) con base en la teoría fundamentada y la aplicación del cuestionario OHIP-14 (Oral Health Impact Profile) que mide el grado de afectación en la calidad de vida (modelo teórico de Locker).

Resultado:

Se identifican los factores psicosociales que presenta esta población, así como la afectación emocional y a nivel social que provoca el diagnóstico de enfermedad periodontal. Los resultados muestran una afectación en la calidad de vida de la población de 1,46 en una escala de 0-4, donde 4 es la máxima afectación. Las participantes femeninas mostraron mayor nivel de afectación en la calidad de vida (1,54) en comparación con los hombres (1,36). A mayor grado de instrucción más afectación en la calidad de vida.

Conclusiones:

Existe una limitación en el enfoque biomédico en la atención de pacientes odontológicos, y por tanto la necesidad de realizar un abordaje integral en pacientes con enfermedad periodontal. Los profesionales odontólogos deben tener un enfoque biopsicosocial en la atención debido a la complejidad que presenta la enfermedad periodontal.

Palabras clave: calidad de vida; enfermedades periodontales; efecto biopsicosocial

Objetivos:

Identificar os aspectos psicossociais da doença periodontal e sua incidência na qualidade de vida das pessoas que sofrem com a doença.

Métodos:

Foi realizado um estudo quantitativo e qualitativo misto. Os instrumentos utilizados foram: entrevista (semiestruturada), fundamentada na teoria fundamentada em dados, e aplicação do questionário OHIP-14 (Perfil de Impacto na Saúde Oral), que mede o grau de comprometimento da qualidade de vida (modelo teórico de Locker).

Resultado:

são identificados os fatores psicossociais que essa população apresenta, bem como a afetação emocional e social que causa o diagnóstico de doença periodontal. Os resultados mostram uma afetação na qualidade de vida da população de 1,46 em uma escala de 0-4, onde 4 é a afetação máxima. As participantes do sexo feminino apresentaram maior nível de comprometimento da qualidade de vida (1,54) em comparação aos homens (1,36). Quanto maior o grau de escolaridade, mais a qualidade de vida será afetada.

Conclusões:

A limitação da abordagem biomédica no cuidado de pacientes odontológicos e a necessidade de realizar uma abordagem abrangente em pacientes com doença periodontal são evidentes. Os profissionais de odontologia devem ter uma abordagem biopsicossocial ao atendimento devido à complexidade da doença periodontal.

Palavras-chave: qualidade de vida; doenças periodontais; efeito biopsicossocial

Introduction and background

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with biofilm and characterized by the progressive destruction of the dental support apparatus. Its manifestations are clinical attachment loss (CAL), bone resorption, periodontal pocket, and gingival bleeding (1.

Periodontal disease is a chronic disease that affects 90% of the world’s population 2. In Uruguay, periodontitis affects 30% of the population over the age of 35 3. It affects the oral cavity and can also cause tooth loss. Additionally, it is related to other systemic diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity 4-6.

It is necessary to adopt a comprehensive approach that includes all the process components to understand the disease entirely. The study this paper is based on aims to create knowledge from an integral perspective and to identify the psychosocial factors of periodontal disease. Dental studies tend to be biomedical. This has been the lens through which periodontal disease and its care approach have been researched. Our literature review has shown a gap in dental studies on periodontal disease from the patients’ psychosocial perspective. This evidences the lack of relevant qualitative studies (7. So far, studies of the Uruguayan population’s subjective implications (thoughts, dear ones, behaviors, etc.) have not been identified.

Contributions from other disciplines must be considered to analyze these aspects that affect people suffering from the disease. In this sense, Health Psychology helps understand these factors that unfold in pathologies such as periodontal disease.

Psychological factors play a significant role in the etiology of various diseases. This illness cannot be attributed to psychological factors with certainty, but it can be prevented by acting on such factors 8.

Elter further argues that mental health problems make periodontal disease progress faster through decreased self-care practices, changes in nutrition, increased smoking, and other harmful behaviors such as bruxism 9.

Emotions can also affect the immune and endocrine response, making individuals more prone to psychosomatic diseases, social isolation, depression, and anxiety, etc. Stress appears because people feel that the disease is overwhelming and that they cannot control it (10.

Chronic illnesses make patients experience uncertainty, dependence, pain, functional limitations, and emotions that have negative consequences (sadness, fear, anxiety, and anger) 11.

Subjectively, chronic illnesses involve a grieving process since they are a turning point in people’s lives. Grieving entails facing the loss of who the person was before the illness, who they will never be again, and who they can no longer be 11-12.

Alfonso states that these pathologies have an underlying set of attributes that arise from their sociocultural and historical evaluation. These attributes affect the relevance of symptoms, the fear they create, their aggressive component, and disease development (13.

Individuals live in a complex and dynamic social environment 14-15. Similarly, humans have needs that can only be met through interaction with others. It is essential to feel recognized and esteemed by others 8.

This means that some diseases also carry a social stigma that creates attitudes and actions of rejection or neglect towards sufferers 16. According to Goffman, these negatively valued attributes create feelings of shame and humiliation 16. In this sense, this social stigma has adverse effects on health status, quality of life, and the process of some diseases 16.

Patients with periodontal disease have feelings of shame and guilt due to their oral health (17. Missing teeth can negatively impact the patient’s self-esteem, confidence, and connection with their environment (problems at work, interpersonal relationships, school relationships, among others). When patients feel that their smile is not aesthetically acceptable, this may influence how they behave toward others (avoiding social contact, apathy, carelessness, etc.) and self-care 17.

Periodontal disease could thus affect the quality of life of those suffering from it 7.

The term quality of life has been used in biomedical sciences since the 1960s and 1970s. It is connected to health, therapeutics, and treatment outcomes 18-19. This link is attributed to the growing need for data from patients: their experiences, satisfaction factors, and concerns 18-19.

In the current millennium and based on the contributions of other health and social sciences, quality of life is defined through objective and subjective dimensions. The objective dimension is determined by external factors such as economic, sociopolitical, and cultural factors that favor or hinder human development. The subjective dimension is expressed through patients’ appreciation of their own lives 20.

Walker claims that this subjective dimension relates to well-being, life satisfaction, self-reporting of health, and physical and mental health 21.

Materials and methods

The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Dentistry of the Universidad de la República (UdelaR) (File 091900-000116-19) and notified to the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, UdelaR (2019). Various ethical and bioethical principles included in several declarations were considered, among them the Helsinki Declaration 22.

It was a quantitative-qualitative mixed methodological design that included a semi-structured interview based on grounded theory and the OHIP-14 questionnaire (Oral Health Impact Profile) 23.

The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed with the participants’ consent.

The sample was selected from a list of patients treated at the Periodontics Clinic at UdelaR’s School of Dentistry between March 2017 and December 2019. The inclusion criteria for the sample were adult patients treated at the Periodontics Clinic of the School of Dentistry (UdelaR). The exclusion criteria were patients with mental disorders or any other illness preventing them from fully understanding the information provided. The fieldwork was performed by a single operator (AA). The sample size was adjusted to the data saturation criterion found when analyzing the interviews.

An interpretative analysis of the patients’ discourse was performed.

MaxQDA® was used in the interpretation process as a technological and support tool to classify, analyze and triangulate the information.

The interview questions were written based on the literature on health psychology and periodontal disease 18,24-26. The interview included questions using simple language. Furthermore, the researcher considered the need for a comfortable environment so participants would feel at ease when answering the questions.

Memoranda were drawn up to include the researcher perceptions and record participants’ reactions, including when their emotional state led them to cry or other emotional manifestations.

An analytical procedure was followed to construct a data-based theory (Grounded theory). Conceptualizations were then developed 27.

The validated OHIP-14 oral health impact profile questionnaire included 14 questions. This enabled researcher to evaluate how often a person has difficulty fulfilling certain functions and how their oral health problems impact the quality of their everyday life23,28-29. Each question has a value ranging from 0 to 4. RStudio 4.0.3 for Windows was used to analyze the data. Rcmdr and sjPlot packages were used to perform the type of statistical analysis for each variable.

The questionnaire collected demographic data to help characterize the participants. The following variables were studied: age, sex at birth, ethnicity, current place of dental care, and educational level.

Analysis of results

Twenty-one subjects participated: 52.4% women and 47.6% men.

Ages ranged between 25 and 66; the average age was 49.57 years (SD = 11.37 years). The people under 40 amounted to 14.3% of the sample. The 40-49 age group included 8.1% of the participants. As for the rest, 23.8% were aged between 50 and 59, and the remaining 23.8% were aged over 60. Regarding ethnicity, 90.5% identified as white or mestizo, while 9.5% reported being Afrodescendants.

Regarding educational level, 23.8% reported having completed primary school, 19% basic education, 42.9% secondary education, and 14.3% had attended higher education. Eighty-one percent of participants stated that oral health care was provided exclusively at UdelaR’s School of Dentistry, and 19% sought care at the School and in private practices.

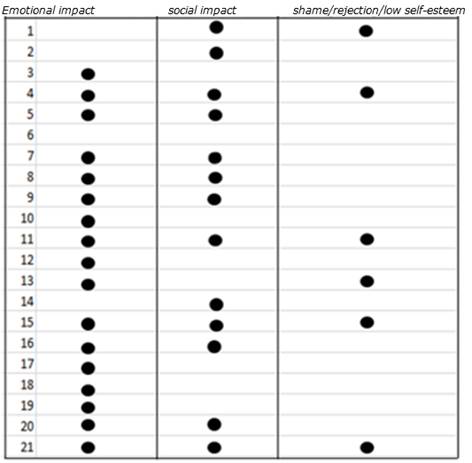

The most significant aspects in the respondents’ discourse were identified:

- emotional impact after periodontal disease diagnosis such as sadness, anger, and fear.

- social impact, where the person shuts off and avoids contact with others.

- feelings of shame, self-rejection, and low self-esteem.

Emotional impact appears in 81% of participant responses. Furthermore, social impact appears in 62% of the responses, and feelings of shame, rejection, and/or low self-esteem are mentioned in 28.5% of cases (Table 1).

Some of the answers to the question What did you feel and/or think when you were diagnosed with periodontal disease?:

... it made me sad, I felt depressed... (woman, 33 years old)

... I rejected myself... (woman, 42 years old)

... I felt so much rage; I feel frustrated... (woman, 33 years old)

...you feel diminished, it’s a terrible feeling...(man, 65 years old)

Participants went through states of depression and sadness.

...I came out crying; I wanted to die... (woman, 48 years old)

...I don’t want to know about the disease because I can get depressed... (woman, 56 years old)

Similarly, participants expressed that periodontal disease had an impact on their bonds and social relationships. In some cases, it led to isolation and low self-esteem. In others, the condition led to feelings of guilt and anger.

... my self-esteem plummeted because teeth are how you introduce yourself... (woman, 53 years old)

... when you talk to someone and they can feel your bad breath, all the doors close... (man, 48 years old)

... I’m ashamed to laugh... (woman, 33 years old)

Participants feel stigmatized, discriminated against, and poorly understood by others. Similarly, they argue that the disease has social disadvantages. This translates into isolation and social distancing.

... I avoid meetings and many things because my teeth aren’t healthy... (man, 66 years old)

... My girlfriend and I separated because of it; she will never understand what this disease is and what it did to me... (man, 49 years old)

This population avoids smiling. They claim to have more significant difficulty in accessing the labor market due to periodontal disease.

The participants expressed concern, fear, and sadness about losing their teeth and the consequences that this may have on their lives.

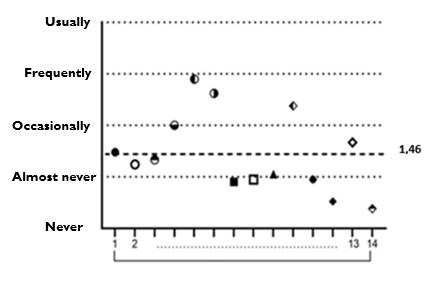

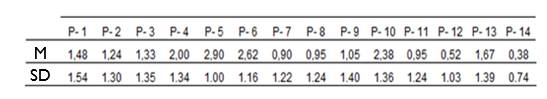

Regarding quality of life, the OHIP-14 questionnaire provided the following information: the participants’ impact level was 1.46 (SD = 1.43) on average (Figure 1); the minimum score was 0.38, and the maximum, 2.90 (Table 2). The scale ranges from 0 to 4, where 4 is the maximum impact, affecting the quality of life of patients with periodontal disease.

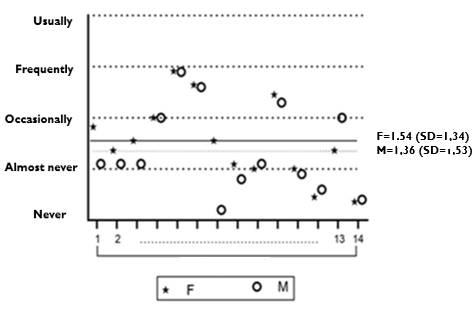

Women showed a higher level of impairment in quality of life compared to men (Figure 2).

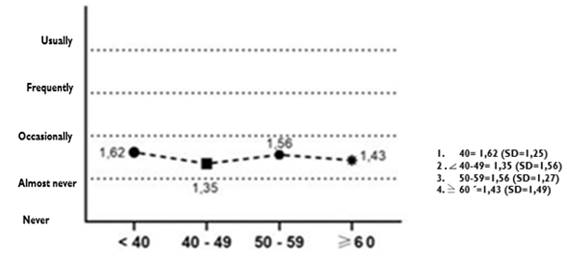

The age variable did not influence the level of impact on quality of life (Figure 3).

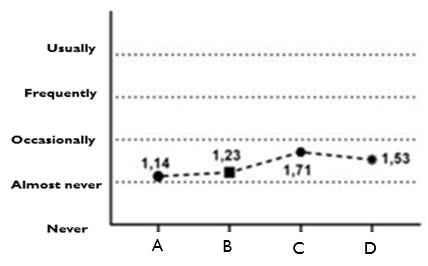

Regarding educational level, we observed that the higher the educational level reached, the greater the impact. (Figure 4)

Discussion

The study results are in line with the conclusions of other investigations throughout the world 8,10,15-17,30. The population studied shows that the emotional and social factors are especially relevant in periodontal disease as they appear very frequently in the responses 10,17.

Lack of motivation, low self-esteem, feelings of shame, and discrimination feature profusely in the participants’ discourse. Every participant’s thoughts and feelings are affected to varying degrees. They avoid smiling, which affects their contact and relationships with others. The look and the smile are essential attributes in our society when we interact with others. It is through them that we express our moods, our openness to interact, etc. These patients reject themselves and feel limited when they interact and socialize. Evidence shows that oral health is a significant component in their quality of life, impacting their overall health. There is agreement in the literature that the approval and esteem of others are important factors for mental health 8.

Participants report depression. According to studies, the depression caused by this disease has a negative impact on periodontal treatment results 9. Depression exacerbates periodontal disease by reducing immune system function and creating a state of inflammation10.

Additionally, the literature shows that depression can increase poor health behaviors, exacerbate poor oral hygiene, lead to smoking or drinking, an unhealthy diet, and a sedentary lifestyle 25.

Illness takes on an important place that limits people’s development in other areas of life such as work, education, and social life. Their personal image is negative. They feel incompetent and without the confidence to face everyday problems.

The incidence of psychological factors influences the health-disease process 25.

It should be noted that only one participant stated that the disease had no personal incidence.

Female participants with periodontal disease are more affected in their quality of life than male participants. This coincides with the literature that studies the impact on quality of life of other diseases according to gender 31-32. This may be related to the aesthetic prototypes of contemporary society. Women face the highest demands to achieve an aesthetic appearance that follows the socially defined canons of beauty to succeed in the workplace and their personal lives. These canons of beauty-a pleasant smile and perfect teeth-make periodontal disease patients feel devalued. The women who participated in the study express rejection towards themselves (negative self-perception) as they do not achieve the desired image, as mentioned by Muñiz 33.

Furthermore, this study’s population showed that the higher the educational level, the greater the impact of periodontal disease on the quality of life. We did not find a direct association between these variables in the literature. One hypothesis is that people with higher education are more aware of the relevance of personal appearance if we consider that education is a factor of social mobility and labor integration. This is one of the requirements that may be included in some job offers. In a mercantilist society, aesthetics is associated with a social hierarchy that achieves success in life and has greater job competitiveness 34.

The study’s quantitative scale did not enable us to find significant differences in the impact level on the different age groups. This may be because the sample was too small to generalize results. However, people under 40 tend to be more affected. This agrees with the literature consulted 35-36.

Slade states that older people tend to accept health deterioration more naturally and that younger people’s health expectations are higher 36.

Conclusions

This study showed that periodontal disease has a biopsychosocial impact and affects the quality of life of the population surveyed. The emotional impact appeared after the diagnosis.

Dentists need to have a comprehensive overview of their patients and the impact of different factors on periodontal disease. Lifestyle, eating habits, self-care, health-disease conceptions, sociocultural context, among others, may or may not determine treatment success and quality of life of patients. Healthcare professionals need to deploy their capacity for empathy, listening, and good communication skills when caring for their patients so they can identify their needs. Furthermore, the study results allow us to put forward the importance of developing an interdisciplinary approach to periodontal disease to achieve comprehensive care. This is especially the case when considering the various concomitant pathologies that can be associated and the impact on people’s quality of life.

This demonstrates the need for future research lines on the topic to expand the number of participants and consider other sociocultural contexts in our country. The socioeconomic context, ethnicity, sex at birth, age, and educational level are associated with disease occurrence 37. Therefore, a greater number of participants would allow us to better study these variables and their impact on quality of life.

Finally, it is essential to consider the importance of including psychosocial factors in periodontics epidemiological studies. More research needs to be done in the communities to validate instruments to measure these factors.

Knowing the needs of each community will help improve public policies.

Including psychologists in dental clinics is a way to implement multidisciplinary work. Another way is to include validated questionnaires in clinical practice to detect psychosocial factors. This would expand the clinical focus and could be included in the periodontal treatment plan if, for example, stress-relieving techniques are needed.

When psychosocial factors are addressed, we are also addressing the cause of the disease, bearing in mind that these factors determine the individual’s behaviors. This is how we promote health.

Acknowledgments:

VITIS-DENTAID donated materials to the participants.

Maité Souyet. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Roberto Volfovicz. Universidad Católica del Uruguay.

REFERENCES

1. Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, Dietrich T, Feres M, Fine DH, Flemmig TF, Garcia R, Giannobile WV, Graziani F, Greenwell H, Herrera D, Kao RT, Kebschull M, Kinane DF, Kirkwood KL, Kocher T, Kornman KS, Kumar PS, Loos BG, Machtei E, Meng H, Mombelli A, Needleman I, Offenbacher S, Seymour GJ, Teles R, Tonetti MS. Periodontitis: Consensus reporto of Workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Disesases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45(20):162-170 [ Links ]

2. Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. The Lancet. 2005; 366(9499): 1809-20. [ Links ]

3. Lorenzo S, Alvarez R, Andrade E, Piccardo V, Francia A, Massa F, Correa MB, Peres MA. Periodontal conditions and associated factors among adults and the elderly: findings from the first National Oral Health Survey in Uruguay. Cad Saúde Pública. 2015; 31(11): 2425 36. [ Links ]

4. Graves D, Zhenjiang D, Yingming Y. The impact of diabetes on periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 2020; 82: 214-224. [ Links ]

5. Carrizales E, Ordaz A, Vera R, Flores R. Periodontal disease, systemic inflammation and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2018 Nov;27(11):1327-1334 [ Links ]

6. Martinez M 1, Silvestre J, Silvestre F. Association between obesity and periodontal disease. A systematic review of epidemiological studies and controlled clinical trials. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017; 22 (6): 708-15. [ Links ]

7. Wong L, Yap A, Allen P. Periodontal disease and quality of life: Umbrella review of systematic reviews. J. Periodont. Res.. 2020;00:1-17 10.1111/jre.12805 [ Links ]

8. Kaplan BH, Cassel JC, Gore S. Social support and health. Med Care. 1997; 15 :47-58 [ Links ]

9. Elter J, White A, Gaynes B, Bader J. Relationship of Clinical Depression to Periodontal Treatment Outcome. J Periodontol. 2002; 73: 441-449. [ Links ]

10. Warren KR, Postolache TT, Groer ME, Pinjari O, Kelly DL, Reynolds MA. Role of chronic stress and depression in periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2014; 64(1): 127-38. [ Links ]

11. Dapueto J, Varela B. Modelos y praxis psicológicos en la medicina. Montevideo: Psicología Médica, 2016 [ Links ]

12. Tizón García JL. Componentes psicológicos de la práctica médica, una perspectiva desde la atención primaria. Barcelona: Doyma, 1988. 272p [ Links ]

13. Martín Alfonso L. Aplicaciones de la psicología en el proceso salud enfermedad. Rev Cub Salud Pública 2003; 29(3): 275-281. [ Links ]

14. Peruzzo DC, Benatti BB, Ambrosano GM, Nogueira-Filho GR, Sallum EA, Casati MZ, Nociti FH Jr. A systematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2007; 78: 1491-1504 [ Links ]

15. Moss ME. Exploratory case-control analysis of psychosocial factors and adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996; 67(10): 1060-9. [ Links ]

16. Goffman E. Estigma. La identidad deteriorada. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu, 1963 [ Links ]

17. Abrahamsson K, Wennströma J, Hallbergc U. Patients' Views on Periodontal Disease; Attitudes to Oral Health and Expectancy of Periodontal Treatment: A Qualitative Interview Study. Oral Health Prev Dent 2008; 6: 209-216. [ Links ]

18. Locker D, Allen F. What do measures of "oral health-related quality of life"measure? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;35(6):401-11 [ Links ]

19. Meeberg GA. Quality of life: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 1993; 18: 32- 38. [ Links ]

20. García-Viniegras C, González Benítez I. La categoría bienestar psicológico. Su relación con otras categorías sociales. Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr 2000;16(6):586-92 [ Links ]

21. Walker A. Understanding Quality Of Life in Old Age. Berkshire England: Open University Press, 2005. [ Links ]

22. Declaración de Helsinki de la Asociación Médica Mundial. Gac Med Mex 2001; 137(4): 387-390 [ Links ]

23. Montero J, Bravo M, Albaladejo A, Hernández L, Rosel E. Validation the oral health impact profile (OHIP-14sp) for adults in Spain. Med.Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009;14(1): 44-50 [ Links ]

24. Decker A, Askar H, Tattan M, Taichman R, Wang HL. The assessment of stress, depression, and inflammation as a collective risk factor for periodontal diseases: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investing 2020; 24(1): 1-12. [ Links ]

25. Lacopino A. Relationship between stress, depression and periodontal disease J Can Dent Assoc 2009 Jun;75(5):329-30 [ Links ]

26. Morales Calatayud F. Psicología de la salud. Realizaciones e interrogantes tras cuatro décadas de desarrollo. Rev. Latinoamericana de Ciencia Psicológica. 2012; 4(2): 98-104. [ Links ]

27. Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. En: N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research 1994; p. 273-285 [ Links ]

28. Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-fortn oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997; 25(4):284-90 [ Links ]

29. Slade GD. Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life.: Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. Department of Dental Ecology School of Dentistry. 1997 Disponible en: https://www.adelaide.edu.au/arcpoh/downloads/publications/reports/miscellaneous/measuring-oral-health-and-quality-of-life.pdf [ Links ]

30. Arrivillaga M, Salazar I, Gómez I. Prácticas, creencias y factores del contexto relacionados con estilos de vida de jóvenes y adultos. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Psicología Conductual. 2005;13(1): 19-36 [ Links ]

31. Cavallo F, Zambon A, Borraccino A, Raven-Sieberer U, Torsheim T, Lemma P. HBSC Positive Health Group. Girls growing through adolescence have a higher risk of poor health. Qual Life Res 2006;15: 1577-85. [ Links ]

32. Serra-Sutton V, Rajmil L, Aymerich M. Estrada MD. Desigualtats de genero en la percepció de la salut durant l´adolescencia. Annals de Medicina. 2004; 87: 25-9. [ Links ]

33. Muñiz E. Pensar el cuerpo de las mujeres: cuerpo, belleza y feminidad. Una necesaria miranda feminista. Soc. Estado 2014; 29(2). Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-69922014000200006 [ Links ]

34. Solano F, Ortiz V. La estetización del mercado laboral: modelos estéticos demandados por el trabajo en las sociedades contemporáneas. Antropol. Sociol. 2015; 17(2): 15-36 [ Links ]

35. León S, Bravo-Cavicchioli D, Correa-Beltrán G, Giacaman R. Validation of the spanish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14Sp) in elderly Chileans. BMC Oral Health. 2014; 14:95 [ Links ]

36. Slade GD, Sanders AE. The paradox of better subjective oral health in older age. J Dent Res 2011; 90 (11): 1279-1285 [ Links ]

37. Oppermann R, Hass A, Kuchenbecker C, Susin C. Epidemiology of periodontal diseases in adults from Latin America. Perodontol.2000 2015; 67(1):13-33. [ Links ]

Authorship contribution: 1) Conception and design of the study: 2) Acquisition of data 3) Data analysis 4) Discussion of results 5) Drafting of the manuscript 6) Approval of the final version of the manuscript AAriceta has contributed in: 1,2,3,4,5,6 LB has contributed in: 1,6 EA has contributed in: 1, 6 AArias has contributed in: 2,4,6

Received: June 23, 2020; Accepted: December 15, 2020

texto en

texto en