Introduction

In the first two decades of the 21st century, South American politics was marked by the emergence of left-wing or center-left governments in what became known as the “Pink Tide”. This regional phenomenon brought significant transformations to national economic and social policies and led to the creation of regional integration initiatives, such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) (Bresser-Pereira, 2010; Lopes and Faria, 2016; Oliveira, 2020; da Silva, 2021; Luciano and Mesquita, 2022. For a critical perspective, see: Moreira, 2006). More recently, the rise of new left-leaning governments has once again drawn political and scholarly attention to the region. This has prompted debate over whether a “new Pink Tide” exists, along with its defining features and future prospects (Delgado and Schugurensky, 2024; Panuzza and Sazo, 2023; Sobottka, 2023; Souza, 2023; Farthing, 2023).

The original Pink Tide was widely interpreted as a regional response to the limits of neoliberal macroeconomic policies implemented in the preceding decades. Section two of this article reviews the relevant literature on the subject. While national experiences varied, a central feature of the Pink Tide was the rejection of the Washington Consensus and the search for post-neoliberal alternatives. Models such as “new developmentalism,” the “economy of buen vivir”, and “21st-century socialism” all emphasized the centrality of the economic dimension in political disputes and shared a rejection of neoliberal economic and social policy as the sole model for governance (Silva, 2018; Oliveira, 2020). As Castañeda (2006) argued in one of the earliest assessments of the Pink Tide, left-wing governments pursued this goal with varying degrees of radicalism.

Reflecting on the possibility of a new Pink Tide, Castañeda (2022) highlights recent leftist victories in the region: Lula da Silva in Brazil and Gustavo Petro in Colombia in 2022; Gabriel Boric in Chile and Pedro Castillo in Peru in 2021 (Castillo was removed from office in 2022); Luis Arce in Bolivia in 2020; and Alberto Fernández in Argentina in 20192. These developments have prompted renewed scholarly debate about whether we are witnessing a new political cycle and, if so, how it compares to the previous one (Panuzza and Sazo, 2023; Sobottka, 2023; Souza, 2023; Farthing, 2023; Delgado and Schugurensky 2024). Recent studies, particularly those by Stuenkel (2022) and Panizza and Sazo (2023), suggest that the electoral success of figures such as Boric and Petro reflects an updated leftist vision. Unlike earlier South American leftist movements, represented, for example, by Lula’s leadership, these “updated” lefts emphasize post-material and cultural agendas, which may be as or more important than economic concerns.

The debate over the new Pink Tide thus introduces into the South American context a discussion long familiar in Global North democracies. The economic or productive dimension of social organization, along with the role of the state in the economy, has historically served as the core axis of political-ideological differentiation between left and right throughout the twentieth century (Downs, 1999). In recent decades, however, both academic literature and political practice have challenged the primacy of this economic cleavage in shaping electoral competition (Inglehart, 1990). Left and right-wing movements alike have increasingly mobilized around alternative agendas, particularly those centered on culture, identity, and values (Hobsbawm, 1996; Noury and Roland, 2020).

This shift raises a theoretical question: to what extent does the current political cycle in South America still revolve around the economic dimension, which traditionally defines left-right differentiation in the region? If, as some scholars suggest (Stuenkel, 2022; Panizza and Sazo, 2023), new leftist movements are increasingly shaped by post-material and identity-based concerns, this may signal a significant departure from the economic-centered logic of the original Pink Tide. Understanding whether this represents a true ideological reconfiguration, or whether the economic cleavage remains central, offers an important contribution to debates about the evolution of political competition in the Global South context.

Considering South America’s recent political trajectory, marked by the enduring tension between neoliberal and post-neoliberal projects, which originally gave rise to the Pink Tide (Flores-Macias, 2012; Oliveira, 2020; Silva, 2018; Rodríguez, 2021), it would be reasonable to expect economic issues to remain central to political competition in the region. Yet, this assumption has been increasingly challenged. As Luna and Kaltwasser (2021) observe, the right has advanced electorally by capitalizing on issues such as crime and gender rights, which are relatively independent of the traditional economic left-right divide.

This study examines the role of the economic dimension in the 2021 and 2022 presidential elections in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. While not covering all recent leftist governments in South America, the electoral victories of Lula, Boric, and Petro are essential to characterizing the “new” Pink Tide as a regional phenomenon. Furthermore, as Stuenkel (2022) and Panizza and Sazo (2023) emphasize, these cases offer contrasting perspectives on the centrality of economic issues within their political-ideological agendas. These elections also occurred in the post-pandemic context, which introduced additional uncertainty into the electoral landscape.

Has political competition in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia moved beyond the traditional economic cleavage that has historically defined the left-right divide? This study hypothesizes that the economic dimension remains a central axis of ideological and programmatic differentiation in the presidential elections of Lula, Boric, and Petro.

To test this hypothesis, the study applies a content analysis approach to 18 presidential campaign platforms: six from Brazil, five from Colombia, and seven from Chile. This sample includes all major presidential candidates from the 2021-2022 elections in the three countries, based on electoral performance. The analysis distinguishes between neoliberal and post-neoliberal emphasis in the campaign documents. The third section presents the study’s findings, which confirm the hypothesis: in all three countries, presidential candidates exhibited substantial differences in their economic policy proposals.

Among the viable presidential contenders in Brazil’s 2022 election, Lula da Silva most clearly embraced a post-neoliberal agenda. The contrast with his main opponent, President Jair Bolsonaro, is striking: Bolsonaro’s platform was firmly rooted in neoliberal principles. In Colombia and Chile, Petro and Boric faced candidates whose platforms also aligned with post-neoliberal ideas. The study shows that Sergio Fajardo in Colombia and Marco Enríquez-Ominami and Eduardo Artés in Chile also rejected the Washington Consensus. Nevertheless, Petro and Boric can be identified as post-neoliberal candidates, as their platforms featured more post-neoliberal than neoliberal proposals. The electoral landscape also included clearly neoliberal options, such as John Milton and Rodolfo Hernández in Colombia, and José Antonio Kast and Franco Parisi in Chile.

As noted earlier, one might expect economic concerns to serve as the organizing axis of these platforms. The original Pink Tide was widely understood as a reaction to neoliberalism and a search for alternative economic models (Bresser-Pereira, 2010; Lopes y Faria, 2016; Oliveira, 2020; Silva, 2021). However, this was not uniformly prominent across all the documents analyzed. In the cases of Boric and Petro, economic visions appear to share space with post-material concerns, such as identity, environmental and territorial issues, which also serve as key frameworks for interpreting national challenges and shaping political responses.

Section four of the article advances the investigation by examining, through the same content analysis strategy, the government programs of left-wing parties associated with the original Pink Tide in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. The analysis sheds light on the contextual specificities shaping the role of left-wing parties within the political landscape of each country. A longitudinal analysis suggests that Lula da Silva’s 2022 candidacy marked an ideological revival of the Partido dos Trabalhadores, with a platform that is considerably more post-neoliberal than those presented two decades earlier. Similarly, when compared to the government programs of the Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia (the center-left coalition that governed Chile following the Pinochet dictatorship), Boric’s platform stands out as significantly more post-neoliberal, echoing the Brazilian case. In Colombia, however, Petro’s government program reflects a degree of ideological moderation relative to the earlier platforms of the Polo Democrático Alternativo, including his own 2010 presidential platform.

The conclusion section discusses these findings. The recent presidential elections in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia were shaped by the same economic cleavage that, twenty years ago, prompted interpretations of the Pink Tide in South America. Lula, Petro, and Boric presented campaign platforms that addressed macroeconomic issues and reflected longstanding tensions between orthodox and developmentalist approaches to economic policy. However, particularly in the cases of Colombia and Chile, leftist alternatives appear to downplay the economic dimension of political and electoral competition.

The analysis suggests that the limitations faced by left-wing parties in Colombia and Chile during the early 2000s, identified in the longitudinal analysis of section four, have been successfully overcome in more recent experiences. In contrast to the original Pink Tide, the current wave of leftist governments in South America cannot be fully explained as a response to neoliberalism. Post-material and cultural debates have gained prominence and must be considered alongside the traditional economic dimension. A nuanced understanding of the “new Pink Tide” and its particularities may be crucial for interpreting the current political cycle in South America and assessing its regional implications.

1. The Washington Consensus and Post-Neoliberalism in South America: Revisiting the Recent Trajectory

Until recently, the prevailing view in Political Science literature was that economic policy decisions constituted the central framework of political and ideological competition. In Latin America after the 1980s, this competition was largely structured around a relatively cohesive macroeconomic paradigm: neoliberalism (Flores-Macias, 2012; Gaviria Ríos, 2004; Ibarra, 2011; Filgueira, 2013). The concept of neoliberalism is multifaceted and has been applied across various fields of study. Specifically, within the context of political and electoral analysis, neoliberalism can be understood as a political ideology that operates at both societal and institutional levels, grounded in a set of principles and propositions derived from economic theory (Stiglitz, 2008; Marangos, 2009).

Although neoliberalism is indeed rooted in economic management techniques, its implementation as public policy in different countries has been significantly shaped by domestic struggles. From a programmatic standpoint, however, neoliberalism maintained a relatively cohesive core agenda. In particular, the notion of the Washington Consensus3 was conceptualized and legitimized as a global neoliberal framework (Naim, 2000). Its policy prescriptions were actively promoted by international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund, particularly as guidelines for countries facing inflationary and external debt crises (Mueller, 2011; Rodrik, 2006). Nevertheless, neoliberalism and the Washington Consensus were also understood as a broader economic development strategy centered on macroeconomic incentives for both domestic and international economic actors.

Neoliberal reform programs were introduced in South American countries throughout the 1980s and 1990s, albeit to different extents (Flores-Macias, 2012; Gaviria Ríos, 2004; Ibarra, 2011; Filgueira, 2013). The political contexts in which neoliberalism was adopted were highly diverse (Ciolli, 2024; Galindo Domínguez, 2024). In some cases, the policy prescriptions of the Washington Consensus were enacted by democratically elected governments, while in others, they were imposed by authoritarian regimes. Even among democratic governments that implemented neoliberal reforms, there is widespread recognition that these reforms often constituted a betrayal of electoral promises (Anderson, 1998; Stokes, 2001). In other words, governments elected on macroeconomic platforms emphasizing welfare protection ultimately adopted neoliberal policies.

The scope and specific measures of neoliberal reforms varied considerably across South American countries, despite their common foundation in the Washington Consensus framework. However, throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, a growing perception emerged among Latin American societies that the promised economic development associated with the neoliberal project was failing to justify the sacrifices in social welfare imposed on the population (Rodríguez, 2021; Ibarra, 2011). This widespread political dissatisfaction fueled the electoral success of forces opposed to orthodox economic policies (Ffrench-Davis y Tjebbes, 2005; Baker y Greene, 2011). As this trend manifested across multiple Latin American countries in the early 2000s, the rise of leftist or progressive governments throughout the subcontinent became widely known as the “Pink Tide” (Lopes y Faria, 2016; Oliveira, 2020).

The Pink Tide period can be broadly situated between the early 2000s and the mid-2010s. During this time, a clear departure from neoliberal frameworks became evident (Bresser-Pereira, 2010; Silva, 2021). Several key policies associated with the Washington Consensus were actively dismantled by progressive governments, including large-scale privatization initiatives, labor market deregulation (Oliveira, 2020), and the liberalization of capital flows (Silva, 2021). However, other elements of the neoliberal agenda remained influential in shaping public policy and electoral discourse. In some Pink Tide administrations, a core component of the Washington Consensus, often referred to as the “macroeconomic tripod”, continued to serve as a guiding principle. This included policies aimed at inflation control, fiscal discipline through budgetary constraints, and a floating exchange rate regime (Biancarelli and Rossi, 2014; Oliveira, 2020).

Unlike the preceding neoliberal era, the Pink Tide did not adhere to a formally defined, coordinated agenda shared across governments. According to Silva (2011), there was significant diversity in political epistemologies, with some administrations embracing traditional developmentalist approaches, while others explored new frameworks centered on environmental concerns, indigenous knowledge systems (Buen Vivir4), or reinterpreted socialist experiences (Socialism of the 21st Century). Consequently, the Pink Tide was characterized by a negative programmatic core, defined primarily by its rejection of the previous neoliberal model and the Washington Consensus. Reflecting this oppositional stance, the term post-neoliberalism was coined to encompass the wide array of ideological and policy orientations that challenged the Washington Consensus framework (Sader and Gentili, 1998; Ruckert, MacDonald, and Proulx, 2016).

The Pink Tide period can be regarded as relatively successful from both an economic and social perspective for South American countries. Indeed, there were tangible improvements in social welfare, as measured by traditional indicators, such as reductions in social inequality (Feierherd et al., 2023). Proactive economic development policies achieved a certain degree of success. However, expectations for a paradigm shift in development models or for greater citizen participation in democratic processes were largely unfulfilled (Sobotkka, 2023; Filgueira, 2013; Ellner, 2020). Additionally, the Pink Tide coincided with a favorable period in the global economy, particularly due to China’s increasing demand for commodities, which played a central role in the export profiles of South American countries (McNelly, 2023; Hawkins, 2024).

Whether because of the 2008 Economic Crisis5, the slowdown in China’s previously high growth rates, or the endogenous limitations of the Pink Tide governments’ strategies, progressive projects in Latin America began to face political and electoral setbacks starting in the second decade of the 21st century (Enríquez and Page, 2018; Luna and Kaltwasser, 2021). In several countries governed by leaders associated with the Pink Tide, opposition politicians were elected, often with the explicit intent of dismantling the post-neoliberal agenda.

If the Pink Tide indeed came to an end around 2015, this conclusion did not always occur in accordance with regular democratic processes (Silva, 2018). Democratically elected Pink Tide governments were removed from power in Paraguay, Brazil, Bolivia. In Venezuela, the continuation of a Pink Tide-affiliated presidency took place outside the framework of a fully competitive electoral process. Thus, the later years of the Pink Tide were marked by significant variation in how political and economic dynamics intersected across different national contexts.

The governments that succeeded the Pink Tide, frequently referred to as the Blue Tide, Conservative Wave, or Right Turn (Rangel and Dutra, 2019; Luna and Kaltwasser, 2021), reversed many of the policies enacted by progressive administrations. At the regional level, international cooperation initiatives were largely abandoned (Guerra and Frisso, 2020; Sanahuja, Hernández Nilson and Burian, 2024). Domestically, neoliberal policies were reintroduced not only as a political-ideological agenda but also as a guiding framework for public policy, albeit with strong conservative elements in the cultural sphere (Bonnet, 2024; Faúndes, 2022).

The governments associated with the Blue Tide faced an economic landscape that was not substantially different from the one at the end of the Pink Tide. That is, they did not benefit from a favorable international context (Luna and Kaltwasser, 2021). With the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic crisis triggered by public health measures and disruptions in global supply chains, economic conditions deteriorated worldwide. Alongside the potential shortcomings of conservative administrations themselves, these factors help explain the resurgence of progressive governments following presidential elections in several South American countries.

There is an ongoing academic debate regarding whether these governments represent a new Pink Tide (Panuzza and Sazo, 2023; Sobottka, 2023; Souza, 2023; Farthing, 2023). Alternatively, it can be argued that these government transitions reflect the normal functioning of domestic democratic processes, without a unifying element across national experiences that would support the characterization of a regional tide. The original Pink Tide is understood as a regional phenomenon in which each national case represented a consequential response to the failure of a broad international initiative that shaped domestic political and economic contexts, namely, the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s and 1990s.

This study aims to contribute to this debate by examining the political-ideological context of the 2021-2022 electoral cycle in three South American countries: Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. In all three cases, the election of presidential candidates identified as progressive supports the hypothesis of a new Pink Tide in South America. Using a content analysis strategy, as outlined in the following section, this research examines the presence of Washington Consensus policies and post-neoliberal alternatives in the campaign platforms of all major presidential candidates. By doing so, the study seeks to assess the extent to which economic policy debates continue to shape the structure of programmatic and electoral competition.

2. Programmatic Disputes in the Presidential Elections of Brazil, Chile, and Colombia: Content Analysis Approaches and Results

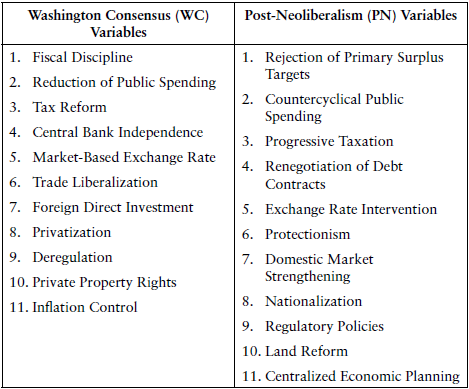

This study employs the content analysis methodology previously developed by Oliveira (2015, 2019, 2020), which is presented in detail in the supplementary document. The strategy employed establishes clear criteria for determining the ideological positioning of parties and candidates. Table 1 below lists the assertions considered in the analysis.

These variables reflect different interpretations of the role of the state and the market, delineating the ideological distinctions between the left (which advocates for greater state intervention) and the right (which emphasizes limited government intervention). The framework seeks to analyze policies associated with the Washington Consensus (Williamson, 1990; Marangos, 2009), such as fiscal discipline, economic deregulation, and privatization, in contrast to state-strengthening initiatives, including increased tax revenues, economic sector regulation, and the expansion of public services. It also encompasses intermediate policy approaches, such as developmentalism and import substitution, both of which have been central to Latin American economic models (Fonseca, 2004; Bruton, 1998).

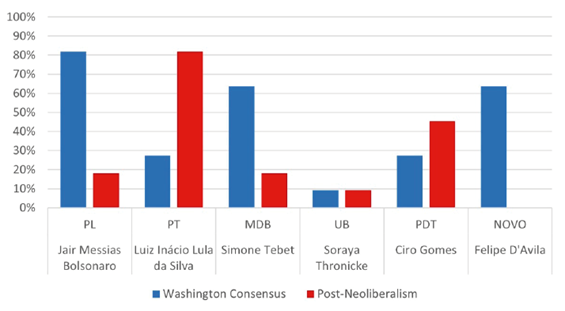

This study analyzes 18 presidential campaign platforms from Chile (2021), Brazil and Colombia (2022). The following section presents the results of this analysis. The figures below display the presence of the variables described in Table 1, expressed as percentages, for each campaign platform examined. Thus, hypothetically, a campaign platform with an indicator score of 100% for the Washington Consensus signifies that the platform contains references to all 11 Washington Consensus variables outlined in Table 1.

The Programmatic Dimension of the 2022 Presidential Election in Brazil

The ideological landscape of Brazil’s 2022 presidential election exhibited significant programmatic diversity. Among the six leading candidates, campaign platforms varied in their economic orientations, with some emphasizing neoliberal policies (Jair Bolsonaro, Felipe D’Avila, and Simone Tebet) and others adopting a predominantly post-neoliberal stance (Lula da Silva and Ciro Gomes), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Washington Consensus and Post-Neoliberalism in Six Presidential Programs in the 2022 Election in Brazil

The two leading candidacies in terms of electoral performance, Lula da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro, exhibited a stark programmatic contrast. Given that the election featured a two-term former president (Lula) and the incumbent president (Bolsonaro), the contest was largely structured around this direct confrontation. The ideological divergence between their campaign platforms suggests that each candidate occupied clearly distinguishable electoral appeal spaces.

Jair Bolsonaro’s campaign platform can be classified as neoliberal, as it includes nine out of eleven Washington Consensus principles. It emphasizes inflation control, central bank independence, fiscal discipline, trade liberalization, tax reform, labor deregulation, and privatization (Bolsonaro, 2022). For example, it reaffirms Brazil’s commitment to inflation targeting, aims to reduce public debt, seeks trade liberalization, and promotes denationalization and deregulation: “Denationalization, privatization, and concessions to the private sector are fundamental” (Bolsonaro, 2022, p. 36).

However, the platform also incorporates three post-neoliberal elements: anti-monopoly regulation, support for union rights, and countercyclical economic policies. The first two serve as moderating elements within an otherwise neoliberal framework, acknowledging potential negative externalities of deregulation. The countercyclical policies, rooted in a Keynesian approach, were framed primarily as a response to the economic effects of COVID-19 and a justification to pre-election fiscal stimulus measures.

In contrast, Lula da Silva’s campaign platform embraced nine of the eleven post-neoliberal variables, while referencing only three Washington Consensus principles. Regarding post-neoliberal policies, the platform explicitly advocated for progressive taxation, stating: “a simpler and more progressive tax structure” (Lula da Silva, 2022, p. 11). It also strongly opposed the privatization and denationalization of state-owned enterprises: “We strongly oppose the ongoing privatization of Petrobras and Pré-Sal Petróleo S.A.” (Lula da Silva, 2022, p. 14). Additionally, the platform emphasized strengthening labor market regulations: “Negotiation of a new labor law with extensive social protections”. It further included countercyclical economic policies, a development strategy centered on the domestic market, and the revival of agrarian reform initiatives.

Lula’s platform departs from the macroeconomic tripod, as it does not endorse strict fiscal discipline. The program explicitly states: “It is necessary to repeal the spending cap and revise Brazil’s current fiscal framework, which is currently dysfunctional and lacks credibility” (Lula da Silva, 2022, p. 10). Although the platform references the sustainability of fiscal policy, it does not explicitly mention fiscal discipline, deficit reduction, or a commitment to achieving a fiscal surplus. Additionally, it advocates for exchange rate management, albeit within the existing policy framework: “Reducing the volatility of the Brazilian currency through exchange rate policy is also a way to mitigate the inflationary impacts of external shocks” (Lula da Silva, 2022, p. 11).

However, the platform maintains inflation control as a central objective of economic management: “A top priority is to coordinate economic policy to combat inflation” (Lula da Silva, 2022, p. 11). In addition, it includes two additional policy measures that align with elements of the Washington Consensus, emphasizing the need to enhance Brazil’s competitiveness through deregulation and trade agreements: “Strengthening Brazil’s competitiveness will be a priority for the new government, which will implement effective measures to reduce bureaucracy, lower capital costs, and expand international trade agreements” (Lula da Silva, 2022, p. 12).

The analysis of the campaign platforms of the two leading candidates in the 2022 Brazilian presidential election reveals clear and distinct economic policy proposals. While both platforms include minor concessions that soften their ideological “purity,” they remain firmly anchored in specific and contrasting economic policy frameworks. Jair Bolsonaro’s platform adhered to a neoliberal model, whereas Lula da Silva, departing significantly from the economic approach of his 2002 and 2006 candidacies, presented a post-neoliberal program, one that does not fully align even with the macroeconomic tripod paradigm.

Following the application of the proposed methodological framework to the 2022 Brazilian presidential candidates’ platforms, it is evident that economic ideology served as a key differentiating factor among the competing proposals. Not only did the two leading candidates, Jair Bolsonaro and Lula da Silva, represent clearly opposing economic visions, but most of the other contenders positioned themselves along the Washington Consensus/post-neoliberalism divide. Apart from Felipe D’Ávila’s radical neoliberal proposal, all other platforms incorporated some degree of mediation between neoliberal and post-neoliberal perspectives. This tendency toward compromise and hybridization of economic policy orientations is not a new phenomenon. The findings suggest that, in the 2022 Brazilian presidential election, the economic dimension remained central not only for ideologically distinguishing the competing platforms but also for shaping the broader programmatic vision articulated, at least in the campaign proposal of Lula da Silva.

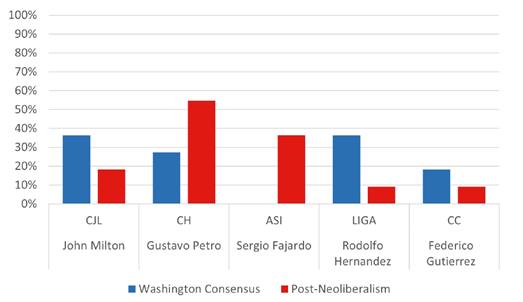

The Programmatic Dimension of the 2022 Presidential Election in Colombia

The first round of Colombia’s 2022 presidential election featured three candidates with strong electoral performances. Gustavo Petro secured the highest vote share and later won the runoff election. Rodolfo Hernández and Federico Gutiérrez competed closely for second place, with Hernández ultimately advancing to the runoff. Two additional candidates, Sergio Fajardo and John Milton, garnered lower vote shares. The programmatic dimension of the presidential contest, illustrated in Figure 2, reveals a narrower ideological spectrum.

Figure 2. Washington Consensus and Post-Neoliberalism in Five Presidential Programs in the 2022 Election in Colombia

The campaign platform of the winning candidate, Gustavo Petro, reflects a clear commitment to economic planning, consistent with post-neoliberal principles. His platform states: “The State will exercise a leadership role to promote a democratic and responsible process of industrialization, one that fosters productivity growth and employment” (Petro, 2022, p. 23). Although the platform’s rhetorical framing is somewhat ambiguous, its substantive policy proposals seek to integrate developmentalist strategies with key elements of the Washington Consensus, such as the autonomy of the Central Bank (Banco de la República), fiscal discipline, external debt repayment, and inflation control:

Macroeconomic stability will be pursued in service of the public, which entails an integrated and functional approach to finance, where employment, income distribution, and sources of growth are given the same importance as debt repayment and inflation control. (Petro, 2022, p. 20).

Other elements of Petro’s platform are clearly aligned with post-neoliberalism, including proposals to renegotiate free trade agreements, impose conditions on foreign investment, implement progressive taxation, regulate labor rights (particularly concerning remote work), promote import substitution, and pursue agrarian reform. Thus, it can be inferred that Gustavo Petro’s campaign platform draws upon traditional economic debates in Latin America, adopting a moderate strategy that has been frequently observed in the region’s political landscape. However, economic development does not occupy a central position in Petro’s government program. Instead, the emphasis falls on the relationship between the economy and environmental and territorial issues: “We will move toward an economy that makes life possible and transform our way of producing into more democratic forms, in harmony with nature” (Petro, 2022, p. 18).

Rodolfo Hernández’s campaign platform (Hernández, 2022) is coherently neoliberal. It supports Colombia’s existing free trade agreements, advocates for tax reform favorable to the business sector, and promotes greater labor market flexibility. Although it does not explicitly incorporate core macroeconomic policies from the Washington Consensus, it includes key elements of the neoliberal agenda that directly appeal to specific social and economic groups. The only policy proposal classified as post-neoliberal, industrial protectionism against imports from Asia and Africa, is also framed within a pro-business perspective favoring domestic enterprises.

Among the low-performing candidates, John Milton presents a strongly neoliberal platform, whereas Sergio Fajardo aligns with post-neoliberalism. However, in both cases, the core principles of neoliberal macroeconomic policy, such as the macroeconomic tripod, are absent. Instead, both candidates rely on specific microeconomic proposals to structure their policy frameworks. Among the Washington Consensus-aligned policies in John Milton’s platform, key elements include openness to foreign direct investment, tax reduction, deregulation to improve the business environment, public spending cuts, and property rights protections. Conversely, Sergio Fajardo’s platform is structured around post-neoliberal principles, emphasizing progressive taxation, labor protections, conditional requirements for foreign direct investment, and strengthening the domestic market. However, both candidates incorporate some degree of protectionism aimed at safeguarding national production.

As previously highlighted, the campaign platforms of Colombia’s 2022 presidential candidates exhibit weaker alignment with the economic variables analyzed. Only Gustavo Petro’s platform predominantly reflects a post-neoliberal orientation. Even in the case of Sergio Fajardo, whose platform exclusively emphasizes post-neoliberal policies, there is no clear ideological coherence underpinning its overall framework. Thus, the economic dimension of political-ideological competition is less pronounced in Colombia compared to Brazil. Nonetheless, the analysis reveals clear distinctions among the candidates, particularly between those who advanced to the second round. The contrast between Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández is particularly striking, as their economic policy orientations reflect distinct ideological positions.

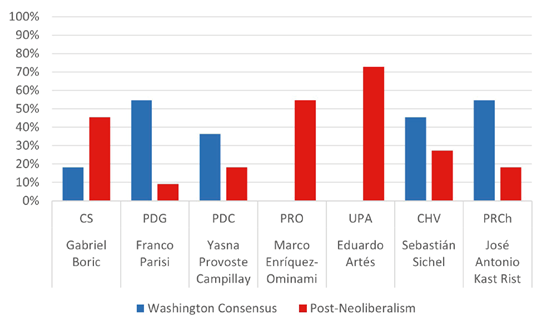

The Programmatic Dimension of the 2021 Presidential Election in Chile

The 2021 Chilean presidential election featured seven candidates. According to the content analysis, three candidates (Gabriel Boric, Marco Enríquez-Ominami, and Eduardo Artés) presented campaign platforms predominantly aligned with post-neoliberalism. The remaining four candidates (Franco Parisi, Yasna Provoste, Sebastián Sichel, and José Antonio Kast) ran on platforms primarily emphasizing policies associated with the Washington Consensus.

The first-round results revealed a fragmented electoral landscape, as the two leading candidates, José Antonio Kast and Gabriel Boric, each secured approximately 25% of the vote. Meanwhile, Franco Parisi, Sebastián Sichel, and Yasna Provoste each received around 12%. Marco Enríquez-Ominami obtained 7.6%, and Eduardo Artés garnered 1.5% of the vote. In the runoff election, Gabriel Boric emerged victorious, securing the presidency.

Figure 3. Washington Consensus and Post-Neoliberalism in Five Presidential Programs in the 2022 Election in Chile

The two leading candidates, Gabriel Boric and José Antonio Kast, presented markedly different economic policy platforms. Gabriel Boric’s platform aligns with post-neoliberalism, though it does not incorporate more than half of the studied emphases, nor does it provide a systematic macroeconomic framework. The program explicitly states:

We must change the productive matrix and establish one that aligns with the country’s desirable development objectives, incorporating industrial and innovation policies that address current challenges while integrating cross-cutting themes such as feminism, the socio-ecological transition, decentralization, and the creation of decent employment. (Boric, 2021, pp. 62-63).

Boric’s platform is notable for its integration of economic and productive policies with gender and environmental perspectives. For instance, it proposes a review of trade agreements and foreign investment regulations based on environmental concerns (Boric, 2021, p.94). It also asserts that its proposals “contemplate a strategic role for the State” (Boric, 2021, p.63), which is further elaborated through measures such as technological development incentives and direct state interventions, including the creation of a public lithium mining company (Boric, 2021, p. 84). Nevertheless, the underlying message of Boric’s platform is that economic strategies will be subordinated to social and environmental commitments.

Traditionally, the protection of the domestic economy would be expected to take precedence. However, Boric’s platform does not engage with traditional macroeconomic policy elements. When addressing fiscal policy, particularly deficit reduction, which is typically associated with neoliberal orthodoxy, the program instead advocates for a significant expansion of the tax base (Boric, 2021, p. 165). Regarding the strategic use of public spending, a longstanding policy debate, the platform explicitly states: “We will strengthen the strategic orientation of public spending in accordance with the priorities outlined in the Framework Law for Inclusive and Environmentally Sustainable Social Development” (Boric, 2021, p. 164).

José Antonio Kast’s campaign platform (2021) presents a decisively neoliberal agenda. His program articulates a strong ideological commitment to free markets and property rights, explicitly stating:

Guaranteeing the freedom of entrepreneurship through unwavering adherence to the rule of law, private property, free competition, and free trade, within a framework of openness to international trade. Maintaining and expanding Free Trade Agreements with all countries worldwide. (Kast, 2021, p. 102).

His platform advocates for reducing the tax base and public spending (Kast, 2021, pp. 70-68) as well as for greater labor market flexibility (p. 72). Instances of post-neoliberal policies are incidental, limited to progressive taxation and anti-monopoly measures. While Kast’s platform maintains a clearly neoliberal vision, it does not explicitly include traditional macroeconomic policy elements, although these principles remain institutionally embedded in Chile’s economic framework.

In the 2021 Chilean presidential election, Franco Parisi, Yasna Provoste, and Sebastián Sichel presented platforms aligned with neoliberal principles, mirroring Kast’s market-oriented economic agenda. Their proposals emphasized private-sector incentives, fiscal austerity, and foreign direct investment as a core development strategy, with only limited and peripheral post-neoliberal elements (primarily concerning labor regulation and selective support for progressive taxation). In contrast, Marco Enríquez-Ominami and the low-polling candidate Eduardo Artés advanced explicitly post-neoliberal platforms, consistently rejecting neoliberal economic tenets. Both candidates advocated for a stronger state role in economic development and social welfare, with no adherence to Washington Consensus policies.

3. Cross-National and Longitudinal Patterns in Left-Wing Party Programs in Brazil, Colombia, and Chile

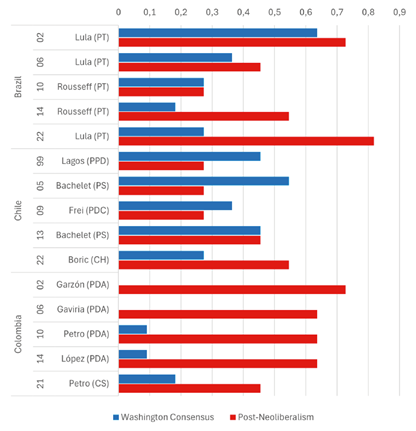

As previously highlighted, in recent Latin American history, the economic dimension of political competition has largely revolved around the Washington Consensus and its rejection, the post-neoliberalism (Flores-Macias, 2012; Gaviria Ríos, 2004; Ibarra, 2011; Filgueira, 2013; Ffrench-Davis and Tjebbes, 2005; Baker and Greene, 2011; Lopes and Faria, 2016; Oliveira, 2020; Silva, 2011). This section of the study aims to relate this proposition to the prior analysis of the electoral platforms associated with the “new” Pink Tide in Brazil, Colombia, and Chile. Figure 4 presents the findings of the previously discussed content analysis, conducted from a cross-national and longitudinal perspective, incorporating government programs from the initial phase of the Pink Tide.

For Brazil, the analysis includes the presidential elections from 2002 to 2014, during which the Workers’ Party (PT) elected Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff. In the case of Chile, the programs of the “Concertación” coalition were considered for the elections from 1999 to 2013, including the 2009 election, in which the coalition’s candidate was defeated. Finally, for Colombia, the analysis covers the elections from 2002 to 2014 and the government programs of the Alternative Democratic Pole (Polo Democrático Alternativo, PDA). The party was widely recognized as Colombia’s main left-wing political force during this period, although it never won the presidency (not even with Gustavo Petro, who ran as the party’s candidate in 2010).

Figure 4. Washington Consensus and Post-Neoliberalism in 15 Presidential Programs in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia (selected parties, 1999-2022)

Lula da Silva’s 2022 candidacy exhibits the highest number of post-neoliberal emphases among all Workers’ Party (PT) presidential platforms since 2002. The 2002 election is widely regarded as a turning point in the party’s ideological trajectory, marking the adoption of the “macroeconomic tripod” framework (Loureiro and Saad-Filho, 2018). Although the PT gradually moved away from the core tenets of the Washington Consensus in subsequent campaigns, these orientations remained present in its government programs, including in Lula’s 2022 platform. The party’s trajectory with respect to the incorporation of post-neoliberal content is particularly revealing. Both in Dilma Rousseff’s 2014 reelection campaign and in Lula’s 2022 bid, the PT advanced platforms that more clearly embraced post-neoliberal principles than those of its earlier successful campaigns.

This evolution presents relevant theoretical implications. The PT endured a period of deep crisis following major political and judicial events, including the Lava Jato investigations, the impeachment of President Rousseff, and a dramatic decline in electoral support after 2016. The evidence presented here suggests that the party responded to this adverse context with a strategy of re-ideologization (rejecting the policy framework associated with the Washington Consensus and aligning itself more closely with post-neoliberal agendas). The relative success of this repositioning is illustrated by the political marginalization of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), the PT’s principal electoral rival in previous presidential contests (Rodrigues and Braga, 2024; Santos and Tanscheit, 2019). In this sense, the emergence of a “new” Pink Tide in Brazil may be understood as a direct consequence of the PT’s strategic reorientation in the face of a critical era6 in the Brazilian party system.

As presented in Figure 4, the Pink Tide in Chile was not particularly radical. In fact, none of the government programs of the former Concertación coalition displayed a majority of post-neoliberal emphases. The platforms of Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet’s first presidential term were developed within a political context dominated by the principles of the Washington Consensus, often criticized in Chile as a lingering legacy of Augusto Pinochet’s economic policies. It may be argued that the Concertación’s privileged position in Chilean politics, although beneficial to the Socialist Party, limited its capacity for ideological adaptation (Oliveira, 2013). The coalition’s inability to respond to the widespread demands for social policy reform expressed during the “Estallido Social” reflects this limitation (Somma and Donoso, 2022). This is evident in the 2021 presidential election, when the coalition’s candidate, Yasna Provoste, presented a platform closely resembling those from the early 2000s (see Figure 3).

Gabriel Boric’s election in 2022 therefore marks Chile’s first experience with a president whose government program explicitly departed from the orientations of the Washington Consensus. Unlike the Brazilian Workers’ Party (PT), which reoriented itself programmatically in response to a critical era, Chile’s center-left failed to adapt to the shifting political landscape. Traditional right-wing parties such as the Independent Democratic Union (UDI) and National Renewal (RN) also performed poorly in the 2022 elections. In addition to the political dynamics of this critical era, the 2017 electoral reform, which increased proportionality in Chile’s electoral system, contributed to heightened party system fragmentation (Jofré and Cabezas, 2025). This fragmentation extended to the presidential arena, influencing the profile of candidates able to advance to the runoff stage.

Gustavo Petro is widely recognized as Colombia’s first leftist president (Wills Otero, 2023). Indeed, Colombia did not participate in the original Pink Tide. Throughout the early 2000s, the country’s main left-wing political force was the Alternative Democratic Pole (Polo Democrático Alternativo, PDA). As shown in Figure 4, the PDA presented clearly post-neoliberal government programs in the four elections held between 2002 and 2014. For instance, when Petro ran for president in 2010 as the PDA’s candidate, the only neoliberal element in his platform was support for international trade agreements.

Although modest, the reduction in the number of post-neoliberal emphases in Petro’s 2021 platform (compared to that of 2010) can be interpreted through the lens of deideologization. Prior research has shown that, over the course of the Pink Tide, parties with longer trajectories in electoral politics tended to moderate their platforms as part of broader strategies to secure the presidency. This was the case of the PT in Brazil and the Frente Amplio in Uruguay (Moreira, 2006; Oliveira, 2020). In Colombia, a distinct political context, shaped by tensions surrounding the 2016 Peace Agreement and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, may have facilitated the unprecedented election of a leftist president. Petro’s 2021 campaign platform suggests that programmatic adjustments did take place, although they remained relatively modest.

Conclusion

The original Pink Tide, which shifted South America’s political landscape to the left, emerged as a response to the region’s neoliberal experience. In this regard, it can be understood as both a regional and transnational political phenomenon that helped shape the continent’s political trajectory. By the late 2010s, however, this leftward shift began to reverse, marked by the electoral victories of right-wing and far-right leaders across the region. As noted by Sanahuja and Burian (2024), these neo-patriotic forces promoted liberal or libertarian economic agendas and established transnational networks spanning the Americas and Europe.

Building on recent history and the political context of South America, academic interest has grown around the question of whether a new Pink Tide is emerging on the continent (Delgado and Schugurensky, 2024; Panuzza and Sazo, 2023; Sobottka, 2023; Souza, 2023; Farthing, 2023). This study revisits the role of the economic dimension in structuring political competition in the region, questioning whether economic issues continue to serve as a central axis of ideological differentiation in the recent presidential elections in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia.

The findings suggest that the 2021 and 2022 elections in these three countries share a common ideological structure, defined by a clash between opposing economic models. This confrontation ultimately resulted in the election of left-wing presidents who rejected neoliberalism as articulated in the Washington Consensus. However, it remains uncertain whether these elections reflect a new “tide” or constitute a broader regional political process with transnational features. The analyzed campaign platforms do not appear to converge around a single overarching theme or a shared developmental agenda for South America.

Unlike the original Pink Tide, the recent electoral shifts in South America may be best understood through the lens of domestic political dynamics in Chile, Brazil, and Colombia, rather than as a cohesive regional phenomenon. These elections do not seem to reflect an urgent search for post-neoliberal development models. An alternative explanation, as suggested by Luna and Kaltwasser (2021) regarding the right-wing, is that the economic cleavage may have lost its centrality within the political projects of South America’s left-wing “new” Pink Tide. This appears to be the case particularly in the elections of Petro in Colombia and Boric in Chile.

While the recent leftist victories in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia all reflect a rejection of neoliberal orthodoxy, the political trajectories and programmatic evolutions behind these outcomes reveal distinctions. In Brazil, the Workers’ Party (PT) gradually reoriented its platform in response to a critical era, embracing a clearer post-neoliberal agenda in 2022. By contrast, in Chile and Colombia, the rise of leftist presidents was not the result of established parties’ ideological adaptation, but rather of broader institutional and political shifts. In Chile, the Concertación’s failure to respond to growing demands for reform opened space for new actors, such as Boric, to propose alternatives explicitly critical of the Washington Consensus. In Colombia, Petro’s victory was facilitated less by a significant ideological repositioning and more by a deinstitutionalized party system (Dargent and Muñoz, 2011) and a unique political context. Nonetheless, his platform did reflect an ideological moderation compared to the positions historically associated with the country’s traditional left.

Thus, while the electoral outcomes may appear similar in the “new” Pink Tide, the underlying dynamics suggest that the Brazilian case is more strongly characterized by strategic programmatic realignment within a traditional party, whereas the Chilean and Colombian cases reflect the limitations of existing party structures and the emergence of new political forces.

Concluding this discussion, several challenges can be identified for future research on contemporary politics in South America. It is essential to deepen our understanding of the ongoing transformations in ideological dynamics, which appear to affect both left and right-wing political forces. Considering the centrality of the economic dimension during the original Pink Tide, the idea that current developments represent a continuation of the process initiated in the 2000s may no longer offer the most insightful perspective. Instead, it may be more productive to examine the organizational features of political parties, often characterized by institutional fragility, particularly in light of the recent period of change that constitutes a critical era for party systems across several South American countries.