The digitalization of the 21st-century has reconfigured the social and behavioral landscape of our society, allowing unprecedented access to information, communication, and social interaction. However, this digitalization has also presented a series of global challenges and emerging issues, among which cyberstalking can be found (Bocij et al., 2004). Cyberstalking, in general understanding, refers to the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to harass an individual (Silva Santos et al., 2023). However, it is not a universally accepted definition, as there is notable inconsistency among studies regarding the behaviors, criteria, and measures used to operationalize the construct (Wilson et al., 2021). While most researchers agree on certain common distinctions and deliberate and persistent online behaviors to stalk and harass an individual, such as repeatedly sending unwanted messages, posting private information, online surveillance, and threatening physical harm (Council of Europe, 2007; Melton, 2000, 2007; Silva Santos et al., 2023), the literature remains confused regarding a coherent definition, as there is no consensus on the defining features of cyberstalking's nature (Nobles et al., 2014; Thompson & Dennison, 2008; Wilson et al., 2021).

Recent statistics indicate that cyberstalking is an increasingly prevalent phenomenon in Latin America. A report by the Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean; CEPAL) showed that approximately 32 % of internet users in the region have experienced some form of digital harassment, including cyberstalking (CEPAL, 2023). In Argentina specifically, a study conducted by the Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo (National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism; INADI) reported that 33 % of respondents had been targeted by cyberstalking behaviors and discrimination, with a higher prevalence among women and young adults (INADI, 2022). These findings reinforce the urgency of developing effective measures for detecting and addressing cyberstalking in this context. Furthermore, evidence from other Latin American countries suggests that this issue is not limited to a specific region; for instance, recent data from Mexico found that around 20 % of internet users had suffered some form of cyber-aggression in the past year, according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography; INEGI, 2023), aligning with other international findings (Kim, 2023; Villanueva-Blasco et al., 2024).

In recent years, new theories have emerged to explain digital behaviors and provide an updated approach to understanding phenomena such as cyberstalking. One of these theories is the Digital Interaction Model, which explores how digital platforms mediate social interactions and reinforce behaviors such as surveillance or harassment (Smith & Duggan, 2020). This model highlights the role of algorithms in amplifying conflicts and their impact on mental health. On the other hand, the Revised Online Disinhibition Theory emphasizes how anonymity and the lack of immediate consequences in digital environments facilitate aggressive and disruptive behaviors (Chen & Roberts, 2021). This revision underscores the importance of designing technological interventions to mitigate these effects. Additionally, recent research has emphasized the application of the Emotional Regulation Approach in digital environments, which analyzes how negative emotions, such as frustration or envy, can trigger problematic behaviors such as cyberstalking (Durao et al., 2023; Taylor et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 2021). This approach suggests that interventions focused on emotional regulation could be effective in reducing the incidence of this phenomenon (Barberis et al., 2020; Saladino et al., 2024; Yosep et al., 2024). Finally, the Digital Ecosystems Theory highlights how digital environments interact with individual and contextual factors to shape online behaviors (Walker & Green, 2023). This framework provides a holistic perspective that can inform policies and practices aimed at preventing cyberstalking (Abu-Ulbeh et al., 2021).

Despite the lack of consensus on how to measure cyberstalking, various constructions, adaptations, and validations have been carried out with significant results in a variety of fields and contexts. Validations have been conducted on the effects of cyberstalking on victims' mental health (Dreßing et al., 2014), its impact on individuals' economic well-being (Maple et al., 2011), and how it affects interactions and socialization of affected individuals (Sheridan & Grant, 2007). In the educational field, cyberstalking scales have been employed due to the ease of accessing the sample (Etikan et al., 2016; Spitzberg & Hoobler, 2002), but they also come with disadvantages such as sample homogeneity (Cavezza & McEwan, 2014).

One of the first scales created in the academic setting and one of the most widely used, according to a study conducted by Wilson et al. (2021), is the 24-item Cyber Obsessional Pursuit scale (COP) by Spitzberg and Hoobler (2002). According to Hanel and Vione (2016), the lack of representation of experiences from the general population may lead to biases in assessment, especially when it is the reference scale in most studies. Furthermore, it does not include behaviors such as identity theft, GPS tracking, or hacking (Harris & Woodlock, 2019). Another widely employed scale, Intimate Partner Cyberstalking, was created by Smoker and March (2017) and consists of 21 items. Although this scale demonstrates adequate internal consistency, it measures behaviors exclusively related to a current romantic partner. Kircaburun et al. (2018) conducted a study on problematic social media use, for which they designed an 8-item scale divided into three categories of cyberstalking: stalking a current partner, stalking a past or desired partner, and harassing disliked individuals. However, this instrument was only applied dichotomously in the study. Nevertheless, one of the most promising evaluations is that of Silva Santos et al. (2023), who developed a 15-item scale to measure cyberstalking. After verifying the reliability and validity of the instrument, five items were eliminated, resulting in a valid and reliable scale (α = .86).

Regarding age and education level, previous research indicates that cyberstalkers tend to be younger (Fissel & Reyns, 2020), educated, and possess superior technological expertise compared to other harassers (Navarro et al., 2016). Gender-wise, existing studies reveal significant differences in cyberbullying perpetration. Men are more frequently identified as the perpetrators (Fansher & Randa, 2019) compared to women (Pereira et al., 2016). Men are also more prone to repeated attempts at accessing their partners' accounts (Marcum et al., 2017) and may pose a greater threat (Ahlgrim & Terrance, 2018). Conversely, women exhibit heightened levels of cyberstalking within the scope of intimate relationships (Smoker & March, 2017).

Different studies have shown that cyberstalking could be associated with a range of psychological outcomes, such as Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) (Przybylski et al., 2013), Compulsive Internet Use (CIU) (Meerkerk et al., 2009; Tallat et al., 2024), and emotional intelligence (Błachnio & Przepiorka, 2016; D’Arienzo et al., 2019; Sánchez-Pujalte et al., 2023). FoMO is defined as the feeling of anxiety or insecurity that arises from the perception of missing out on important or exciting events (Przybylski et al., 2013). The use of social media platforms, which provide a constant stream of updates about others' activities, has been linked to increase FoMO (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, 2016). Cyberstalking has also been associated with CIU, which is described as an impulse control disorder involving dysfunctional compulsive behavior specific to online activities rather than general internet use (Meerkerk et al., 2009; Muusses et al., 2014; Navarro et al., 2016). A study by Błachnio and Przepiorka (2016) found that individuals with CIU were more likely to engage in cyberstalking behaviors compared to those without it. The authors suggest that the constant need for stimulation and excitement associated with certain online activities may contribute to the development of cyberstalking behaviors. Similarly, D’Arienzo et al. (2019) found that cyberstalkers were more likely to experience FoMO and CIU compared to non-cyberstalkers. The authors suggest that the desire for attention and validation associated with FoMO may lead individuals to engage in cyberstalking behaviors. Additionally, the constant need for stimulation and excitement associated with internet addiction may drive individuals to seek out new victims for cyberstalking.

In this context, emotional intelligence, defined as the ability to identify, understand, and manage one's own and the others' emotions (Al-Sarayra, 2022; Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Salovey et al., 2002; Sánchez-Pujalte et al., 2021), has been recognized as a valuable tool for preventing and reducing the negative effects of cyberstalking (Fissel & Reyns, 2020). By enhancing emotional intelligence, individuals may increase their resilience to stress and anxiety associated with cyberstalking, decrease FoMO, and effectively manage their relationships with digital technologies to avoid compulsive Internet use (Begotti & Acquadro Maran, 2019). Emotional intelligence has been shown to play an important role in social interactions, as individuals with high emotional intelligence are better able to communicate effectively and resolve conflicts (Abiyoga et al., 2024; Goleman, 1995; Sánchez-Pujalte et al., 2021). Additionally, emotional intelligence has been linked to various positive outcomes, including mental health and job performance (Brackett & Salovey, 2006).

Studies have found that individuals with low emotional intelligence are more likely to become victims of cyberstalking (Gross et al., 2016). Furthermore, individuals with low emotional intelligence are more likely to engage in online pursuit of others and exhibit aggressive online behaviors, including cyberstalking (Chen & Lee, 2017). Conversely, cyberstalking can also have a negative impact on emotional intelligence, as victims of cyberstalking may have lower capacity to manage their emotions and establish boundaries with others (Abiyoga et al., 2024; Tokunaga & Rains, 2019). Research has also found a negative correlation between emotional intelligence and cyberstalking perpetration, indicating that individuals with higher emotional intelligence are less likely to engage in cyberstalking (Borrajo et al., 2015). Moreover, individuals with low emotional intelligence are more likely to engage in online harassment, which encompasses cyberstalking (Wolak et al., 2008). This suggests that individuals with low emotional intelligence may lack the ability to regulate their emotions and respond appropriately to situations, thereby engaging in cyberstalking behaviors (Durao et al., 2023). These findings highlight the importance of validating a cyberstalking assessment scale in the Argentine context, as it would not only contribute to the literature but also provide practical implications for detecting and mitigating this behavior. Additionally, understanding the interrelationships between cyberstalking, FoMO, CIU, and emotional intelligence can inform intervention strategies aimed at reducing online harassment and promoting healthier digital habits (Abiyoga et al., 2024).

Given this context and the reported limitations, this study had two main objectives: first, to analyze validity evidence for the Cyberstalking Scale in the Argentine context; and second, to examine its relationships with other emerging digital phenomena, such as CIU and FoMO, as well as the role of emotional intelligence as a protective factor against their negative consequences.

Method

Participants

A geographically online questionnaire was administered with stratified sampling based on the geographical regions of Argentina. Complete and valid protocols totaled 1102 cases, of which 53.90 % (n = 594) were identified as female and 46.10 % (n = 508) were identified as male. The mean age of the participants was 38.21 years (SD = 10.45), and the age range was 18 to 65 years. In terms of education level, 4.7 % of the sample obtained primary education, 32.1 % obtained secondary education, 40.6 % obtained higher education, and 22.6 % obtained university education.

Instruments

Cyberstalking. The Cyberstalking Scale originally created by Silva Santos et al. (2023) consists of nine items that explore various online behaviors related to the construct (e.g., "I've used fake accounts on the internet to interact with someone without revealing my identity") and their favorability towards these actions (e.g., "When you're interested in someone, it's not wrong to look at their acquaintances' social media in order to get to know them better"). According to the authors, such behaviors are not problematic individually but become problematic when they occur collectively and on a regular basis. The response format used was a Likert-type scale with five points, ranging from 1: totally disagree to 5:totally agree.

Compulsive Internet Use. CIU was assessed using the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS; Meerkerk et al., 2009), comprising 14 items that capture excessive Internet usage. The scale is divided into two dimensions: usage and consequences (e.g., "Do you sleep less due to Internet use (email, social media, Google, etc.)?") and problem awareness (e.g., "Have you unsuccessfully tried to spend less time online (email, social media, Google, etc.)?"). Respondents were asked to rate each item on a scale ranging from 0: never to 4: very often, with higher scores indicating a higher level of CIU. The scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency in the original study (α = .81 to α = .91) and for our study (α = .83 to α = .79).

Emotional Intelligence. A reduced 12-item version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS; Salguero et al., 2009), which was derived from the TMMS-24 (Extremera Pacheco & Fernández Berrocal, 2005; Salovey et al., 1995) was used. This scale consists of 12 items defining three dimensions. The first dimension, emotional attention (α = .83; for our study α = .82), represents the ability to control one's emotions and feelings (e.g., “I pay a lot of attention to my emotions''); the dimension of emotional clarity (α = .79; for our study α = .81) refers to the ability to understand and name one's feelings (e.g., "I can usually define my feelings''), and finally, emotional repair (α = .82; for our study α = .77) represents the ability to regulate negative emotional states and prolong positive ones (e.g., "even" when I'm sad sometimes, I usually have an optimistic outlook) .This study used a Likert-type response format ranging from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree.

Fear of Missing Out. To assess the construct, the adaptation and validation (Durao et al., 2024) of the original version of the scale (Przybylski et al., 2013) was use, which consists of 10 items identifying Dimension 1, FoM NI (α = .81; for our study α = .73) (e.g., “I am worried about my friends getting more rewarding experiences") and Dimension 2, FoM SO (α = .78; for our study α = .77) (e.g., "It annoys me when I miss seeing friends"). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree (others in this study the scales used use the same response format). The higher the score on both dimensions, the higher the level of FoMO.

Socio-demographic data questionnaire: Information on the gender, age, self-perceived socio-economic level and highest level of education was collected from the participants.

Procedure and Data Analysis

Individuals who met age (over 18 years) and geographic region criteria were invited to participate via social media based on sampling quotas. Participants first read a brief informed consent form that explained the purpose of the study, the institution responsible for it, and the voluntary nature of the participation. They were informed that they could discontinue the questionnaire at any point without any penalty. And if additional information was needed, they were given an email contact address. All respondents were ensured confidentiality and anonymity of their data, in accordance with the Argentine National Law 25,326 on the Protection of Personal Data. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the institution leading the study, thus guaranteeing compliance with international ethical standards for human subject research (#In0051a).

The statistical analyzes that guided the development of this study were performed using SPSS for Windows software version 19.0 (George & Mallery, 2010). Descriptive statistics for each item in the final version of the scale were computed, including mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. Additionally, a normality test was performed on the structured variables to determine whether parametric statistics could be applied. Then, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine internal validity, and the instrument's internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach's alpha and the Omega index. Finally, to evaluate criterion validity, the relationships between Cyberstalking and TMMS were analyzed using Pearson correlations. Finally, we test the contribution of CIU and FoMO dimensions on Cyberstalking through a regression analysis.

Results

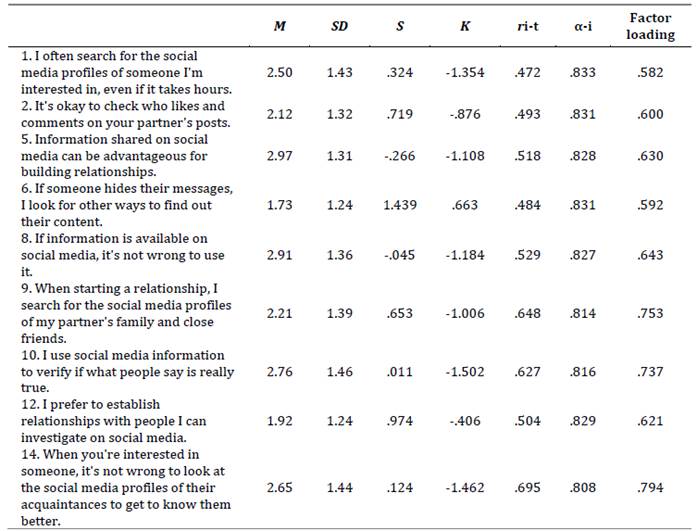

First, descriptive statistics of the items from the Cyberstalking scale were analyzed (Table 1). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted as the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity yielded favorable results (KMO = .890; Bartlett: p < .001).

Table 1: Descriptive analysis of the cyberstalking ítems

Note: M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation; S: Asymmetry; K: kurtosis; ri-t: item-total correlation; α-i: alpha is item is deleted.

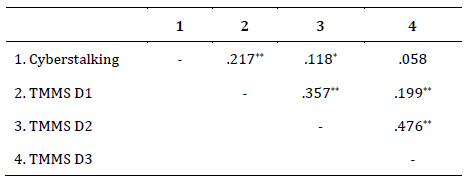

The total percentage of explained variance for the scale was 44.263 %. Regarding internal consistency, it was deemed adequate (α = .841; ω = .853). Subsequently, the relationship between cyberstalking levels and the three dimensions of emotional intelligence were examined (Table 2).

The relationship between cyberstalking and emotional intelligence (Table 2) reveals notable differences across its three dimensions. The strongest association is observed with TMMS - attention to emotions, suggesting that individuals involved in cyberstalking tend to be more aware of their emotions. However, the weaker correlations with TMMS -clarity of emotions and TMMS- emotional regulation indicate that while these individuals may be attuned to their emotions, they do not necessarily possess the clarity or regulation skills to manage them effectively. This finding has important implications, as it suggests that emotional awareness alone is insufficient in mitigating the psychological effects of cyberstalking behaviors.

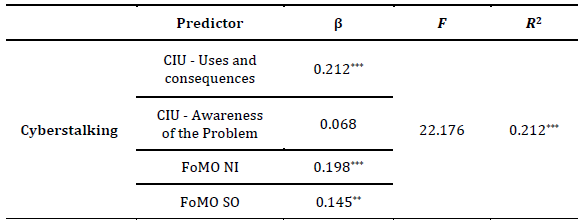

Finally, regression analyses were conducted, with FoMO and CIUS as independent variables, to examine their effects on cyberstalking. In Table 3, it can be observed that the percentage of explained variance is significant, although not very high. Out of the four variables included in the model, CIUS uses and consequences, and the two dimensions of FoMO were found to be significant.

Discussion

Given that cyberstalking has been recognized as a significant emerging threat in the digital age (Bocij et al., 2004; Fissel & Reyns, 2020; Kim, 2023), this study had two main objectives: the validation of the Cyberstalking Scale in Argentina and the analysis of its relationships with variables such as FoMO, CIU, and emotional intelligence. Regarding the first objective, preliminary validity evidence of the scale for assessing cyberstalking in the specific context were presented.

Based on the first objective of the study, the descriptive indicators were adequate for the nine items of the Cyberstalking Scale, with item-total correlations and reliability indices being appropriate, and no improvement resulting from item deletion (Hair et al., 2010). Furthermore, the results showed adequate internal validity of the instrument, as the EFA showed a one-factor model, identifying a dimension for the cyberstalking construct and the reliability index (α = .841; ω= .853) was also adequate. In terms of external validity, it was confirmed that the instrument showed relationships with other constructs and associated variables such as emotional intelligence, which is consistent with previous studies (Durao et al., 2023; Taylor et al, 2022; Wilson et al., 2021). Thus, it is a brief instrument that assesses the level at which participants engage in cyberstalking in their various online interactions. Currently, there is a shortage of designed and validated instruments to assess this issue in individuals involved in online interactions in the Argentinean context.

Regarding the second objective, the findings provided a significant analysis of the links between cyberstalking, FoMO and CIU, areas that have been understudied in the Argentinean context (Etchezahar et al., 2023; Durao et al., 2023; Albalá Genol et al., 2022). Both variables are related to cyberstalking, which is consistent with previous studies that have shown that excessive use of ICTs can lead to problematic online behaviors (Navarro et al., 2016). This phenomenon can be explained through the uses and gratifications theory, which suggests that people use media to satisfy their individual needs and desires (Pereira et al., 2016). In this case, individuals may resort to cyberstalking to satisfy their desires for connection, attention, and/or control, especially if they feel they are missing out on digital practices (FoMO) or have CIU.

The findings of this study have several practical implications. First, some validity evidence of the Cyberstalking Scale can serve as a valuable tool for educators and mental health professionals in Argentina to identify individuals at risk of engaging in or falling victim to cyberstalking. Early identification can facilitate timely interventions, potentially reducing the prevalence of such behaviors. Moreover, the significant links between cyberstalking, FoMO, and CIU suggest that intervention programs should address these underlying factors. Educational workshops focusing on digital literacy and healthy online habits could be implemented in schools and universities. These programs can educate students about the risks associated with excessive Internet use and the importance of emotional regulation in online interactions (Barberis et al., 2020; Yosep et al., 2024). From a policy perspective, the gender differences observed in cyberstalking behaviors highlight the need for targeted strategies (Wilson et al., 2021). Awareness campaigns can be designed to specifically address the higher propensity for men to engage in such behaviors, while support systems can be strengthened to assist women who are more likely to experience negative consequences.

Advancing validity evidence for the cyberstalking scale strengthens the link between theory and practice by providing a reliable tool for detecting and monitoring cyberharassment behaviors in both clinical and educational settings. This means that research insights can be effectively applied to real-world scenarios, ensuring that theoretical knowledge informs practical interventions. In clinical settings, the use of the scale allows professionals to identify early signs of cyberstalking and develop targeted interventions. These interventions can focus on underlying factors such as emotional intelligence, FoMO, and CIU (Begotti & Acquadro Maran, 2019). By addressing issues like FoMO and compulsive online behavior in therapy and incorporating emotional intelligence training, clinicians can help individuals regulate their emotions and reduce cyberstalking tendencies (Tallat et al., 2024). This proactive approach enables timely support for at-risk individuals, bridging the gap between academic research on cyberstalking and therapeutic practice.

In educational environments, the scale serves as a valuable tool for teachers and school counselors to detect students who may be at risk of engaging in or suffering from cyberstalking. Early detection enables the planning of prevention programs that promote responsible digital practices and provide socio-emotional support. For example, schools can implement emotional intelligence education programs to strengthen students’ emotion management skills (Błachnio & Przepiorka, 2016). Additionally, integrating cyberstalking awareness into digital literacy curricula encourages a culture of safe ICT use. Structured school-based interventions can focus on fostering healthy online habits and resilience against online harassment (Villanueva-Blasco et al., 2024), thereby cultivating positive online norms and reducing cyberstalking behaviors.

While this study provides valuable insights, it also opens avenues for future research. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore the causal relationships between cyberstalking, FoMO, CIU, and emotional intelligence. Such studies can help determine whether interventions targeting these factors can effectively reduce cyberstalking behaviors over time. Additionally, qualitative research could delve deeper into the personal experiences of individuals involved in cyberstalking, either as perpetrators or victims. Understanding the motivations and emotional processes underlying these behaviors can inform the development of more tailored and effective intervention strategies.

Conclusion

The observed relationship between cyberstalking, FoMO, and CIU suggests that mitigating these factors could be an effective strategy for preventing cyberstalking. Prevention programs could, for instance, incorporate strategies for managing online time and coping with FoMO-related feelings, aligning with the recommendations of Przybylski et al. (2013). Schools and universities could implement structured intervention programs that emphasize responsible digital behavior and resilience against online harassment. Additionally, fostering positive online community norms through awareness campaigns may help curb cyberstalking behaviors. These initiatives should clearly define what constitutes cyberstalking-such as persistent unwanted online contact and threats (Council of Europe, 2007; Melton, 2000, 2007)-to help individuals recognize and report such actions, reinforcing positive online norms. Furthermore, the findings of this study have potential implications for clinical practice.

Despite its contributions, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that should be considered in future research. First, the study’s cross-sectional correlational design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between the variables of interest (Menard, 2002). Given that cyberstalking, FoMO, compulsive Internet use, and emotional intelligence fluctuate over time, a longitudinal design would allow for a more comprehensive examination of how these variables influence one another. Additionally, an experimental approach would provide greater control over confounding factors and facilitate the identification of causal relationships (Cook et al., 2002). Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights into the relationship between cyberstalking, FoMO, CIU, and emotional intelligence in the Argentinean context. Future research should aim to replicate and expand upon these findings using more rigorous methodologies and more diverse samples.

Moreover, it is essential to further explore the practical implications of these findings for intervention programs and public policies. Educational institutions should integrate mandatory courses on digital citizenship and cybersecurity to equip students with the skills needed to navigate online environments safely. Policymakers should develop and enforce regulations that require online platforms to implement more effective monitoring and prevention mechanisms for cyberstalking. For instance, the algorithm-driven amplification of conflicts on social media-highlighted by Algorithmic Conflict Theory (Smith & Duggan, 2020)-underscores the need for platform designs that prioritize user safety. Additionally, mental health professionals could develop therapeutic interventions aimed at individuals at risk of engaging in or becoming victims of cyberstalking, with a focus on emotional self-regulation and healthier digital habits.