Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Links relacionados

Compartir

Ciencias Psicológicas

versión impresa ISSN 1688-4094versión On-line ISSN 1688-4221

Cienc. Psicol. vol.17 no.2 Montevideo dic. 2023 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2823

Original Articles

Promotion of empathy, self-concept and basic values: an intervention in a female prison

1 Fundação Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco, Brasil, eliasmasc12@gmail.com

2 Fundação Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil

Incarceration of women is permeated by countless structural problems and inefficiency in guaranteeing fundamental rights and psychological assistance to women. In this article, the effects of intervention workshops aimed to promote self-concept, empathy, and basic values for incarcerated women are reviewed. The study comprised 56 women aged between 18 and 63 years, incarcerated in a Public Prison (M = 32.23; SD = 9.25). Fifteen of these women participated in the intervention program, while the remaining sample comprised the control group. Both groups were evaluated in the pre- and post-intervention period, using the Self-Concept Scale, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index and the Basic Values Questionnaire. During the meetings field notes and participant observations were used to describe meaningful experiences. No statistically significant variations were found in the scores of the scales used, which may be related to the need to adapt these instruments to groups with low levels of education. On the other hand, the study found that the use of workshops enabled the construction of a pedagogical space, with very different contingencies compared to the prison environment, in which women were encouraged to experience their emotions and feelings.

Keywords: prisons; women; correctional education; empathy; self concept

O encarceramento feminino é permeado por inúmeras problemáticas estruturais e pela ineficiência na garantia de direitos fundamentais e assistência psicológica às mulheres. Neste artigo, analisam-se os efeitos de oficinas de intervenção para a promoção do autoconceito, da empatia e de valores básicos em mulheres encarceradas. Participaram do estudo 56 mulheres, em uma Cadeia Pública, com idades entre 18 e 63 anos (M = 32,23; DP = 9,25). Quinze destas mulheres participaram do programa de intervenção, enquanto que o restante da amostra compôs o grupo controle. Ambos os grupos foram avaliados no período pré e pós-intervenção, por meio da Escala de Autoconceito, o Interpersonal Reactivity Index e o Questionário de Valores Básicos. Notas de campo e a observação participante foram utilizadas para descrever experiências significativas vivenciadas durante os encontros. Não foram encontradas variações estatisticamente significativas nos escores das escalas empregadas, o que pode estar relacionado à necessidade de adequação desses instrumentos para públicos com baixa escolarização. Em contrapartida, avalia-se que o uso de oficinas possibilitou a construção de um espaço pedagógico, com contingências muito distintas do ambiente carcerário, no qual as mulheres foram estimuladas a experimentar suas emoções e sentimentos.

Palavras-chave: prisões; mulheres; educação de prisioneiros; empatia; autoimagem

El encarcelamiento femenino es permeado por muchas problemáticas estructurales y por la falta de eficacia en la garantía de los derechos fundamentales y la asistencia psicológica a las mujeres. En este artículo se analizan los efectos que tiene los talleres de intervención para la promoción del autoconcepto, de la empatía y de los valores básicos en mujeres encarceladas. Participaron del estudio 56 mujeres, en una cárcel pública, con edades entre de 18 a 63 años (M = 32.23; DE = 9.25). Quince de estas mujeres participaron del programa de intervención, las demás de la muestra compusieron el grupo control. Ambos grupos fueron evaluados en el período de pre y posintervención por medio de la Escala de Autoconcepto, el Interpersonal Reactivity Index y el Cuestionario de Valores Básicos. Las notas de campo y la observación participante fueron utilizadas para describir experiencias significativas vividas durante los encuentros. No fueron encontradas variaciones estadísticamente significativas en los resultados de las escalas empleadas, lo que puede estar relacionado a la necesidad de adecuación de esos instrumentos para públicos con baja escolarización. En cambio, se evalúa que el uso de talleres posibilitó la construcción de un espacio pedagógico con contingencias muy distintas al ambiente carcelario, en el cual las mujeres fueron estimuladas a experimentar sus emociones y sentimientos.

Palabras clave: prisión; mujeres; educación de los presos; empatía; autoconcepto

The problems experienced by prisoners in Brazil, such as the overcrowding of prisons, the lack of work, educational and leisure activities, as well as poor structural, hygienic and sanitary conditions (Brazil, 2017) is widely known. This problem is not directly related to gender, as incarcerated men and women, whether cisgender or transgender, are exposed to the aforementioned conditions on a daily basis (Brazil, 2016).

The organization of the Brazilian prison institutions usually disregards the peculiarities that should be considered when dealing with the female population, despite the exponential growth in the incarceration of women over the years. In this sense, Brazil has seen an increase of more than 600% in the imprisonment of women rate between 2000 and 2016. Currently, Brazil houses the fourth largest female prison population on Earth, with approximately 44,700 women in prison, second only to the United States, China and Russia (Brazil, 2017). Given the complexity of the issues that emerge from crimes and the incarceration of people around the world, psychological variables should contribute to the process of social reintegration, since the failure of the system is reflected in incalculable social damage, in addition to the high financial costs for the state(Barnett et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2014; Robinson & Rogers, 2015).

The progressive increase in incarceration of women coupled with the prison institutions’ inability to meet gender-related demands sharpens the vulnerabilities expressed by this population. The inefficiency of the state in securing these women a space supportive to social demands (work and education), specific demands (pregnancy and puerperium), family demands (daycare nurseries, space to receive family), psychological demands (leisure and mental health promotion), among others (Brazil, 2017), is then emphasized.

The aforementioned precariousness and deficiencies contribute to resocialization system inability to meet its main objective of preparing the inmate to return to society in a dignified way, empowered to exercise their rights and fulfill their duties like any other citizen. However, these factors are not the only ones responsible for the low capacity of Brazil to provide proper conditions for the reintegration of these people into society. This added with a shortage of public policies and intervention programs focused on actions to promote the psychosocial and moral development of incarcerated people, despite the existing robust body of scientific evidence that demonstrates how this type of action contributes to social reintegration.

In many countries, variables such as empathy, self-concept and human values are used as part of the process of assessing people who have committed crimes and attending intervention programs in prisons. In some cases, participation in these programs is even considered part of the sentence and are a condition for the prisoner’s progression to freedom (Barnett et al., 2011; Echeburúa & Fernández-Montalvo, 2007). Training aimed at promoting empathy and self-concept has been used in offender rehabilitation programs as tools targeted to strengthening prosocial behaviors and reducing the factors that favor criminality and, consequently, recidivism(Christopher & McMurran, 2009; Day et al., 2011; Roche et al., 2011).

Empathy may be generally understood as a capacity made of cognitive and affective components that enable it to take a perspective and experience affective responses that are congruent with what one is observing in relation to what other people are feeling (Batson, 2009; Eisenberg et al., 2006; Hoffman, 2000). Empathic experiences are important for regulating life in society, raising social awareness and mediating decision-making processes, especially those aimed at care, respect and morality (Dutra, 2020; Pavarino et al., 2005; Sampaio et al., 2021).

In opposition, lack of empathy has been identified as a mechanism that predicts engagement in aggressive and criminal behaviors (van Zonneveld et al., 2017). Lower levels of empathy would be directly related to antisocial and harmful behaviors (Drayton et al., 2018), crimes such as rape and homicide (Domes et al., 2013) and offending (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004). Empathy deficits appear to be associated with psychopathy (Gehrer et al., 2020; Korponay et al., 2017) in incarcerated people.

When analyzing the differential profile of male offenders in prison with and without psychopathy, Echeburúa and Fernández-Montalvo (2007) found that offenders with psychopathy were not only less empathetic but also had lower self-esteem. In other words, the feeling of satisfaction that a person has about his/herself, one of the components of self-concept, also appears to be compromised in this population.

Self-concept can be defined as the individuals’ perception of themselves, their abilities and their resources, in different situations and stages of life, that build up a concept that will ground the way they read themselves and the world around them (Vaz-Serra & Pocinho, 2001). According to Veiga (2006), self-concept can be summed up in two questions: How do I see myself? And how do I think others see me? When modified by the individual’s experience to the same extent as it modifies the way this experience is perceived, this dialectical movement is influenced by social relationships and the situational context, constituting one of the variables that intervene in human behavior and identity formation (Basílio et al., 2017).

Basílio et al (2017) refer to a certain instability in the self-concept, which is subtly changed over life. Within prisons, these changes are negative and seem to be anchored in the lack of essential elements needed to strengthen the self-concept due to the rigidity of institutional routines and the excess of rules that hinder the personal development of prisoners, impacting on the constructing of their identity (Antunes, 2012; Basílio et al., 2017).

Negative self-concept may be a risk factor for the functional development of incarcerated individuals. This was observed in a study with a sex offender treatment group, in which the post-treatment self-esteem score was the only measure that significantly predicted sexual and/or violent recidivism, among other measures in the socio-affective domain (Barnett et al., 2011). It was also found that the intervention was particularly successful at encouraging men to identify and recognize problems with their self-esteem, which led to a reduction in the rate of new offenses.

Other studies suggest that individuals with lower self-esteem scores also have higher rates of aggression (Webster et al., 2005) and risk of suicide (Vaz-Serra & Pocinho, 2001). Strengthening the self-concept (positive and more stable) would be an important tool toward reducing antisocial behavior, and would make it easier to understand how people in prison adapt their thoughts, values, emotions and behaviors in the most diverse situations (Antunes, 2012; Basílio et al., 2017).

Considering that values represent human needs at cognitive level, transcend specific situations and drive the selection of behaviors and events (Gouveia et al., 2009), one could reasonably assume that values are also, to some extent, associated with the commission of crimes. In this regard, studies show that antisocial behavior is negatively associated with normative values (obedience, religiosity and tradition), suprapersonal values (beauty, knowledge and maturity) and interactive values (affectivity, social support and social harmony) (Formiga & Gouveia, 2005; Medeiros et al., 2015). Criminal behavior is also associated with a strung hunt for satisfaction, pleasure and new sensations, and is present in individuals whose interpersonal relationships are damaged and who value less the compliance with social norms (Gouveia, 2003). Finally, Amorim-Gaudêncio et al. (2023), when reviewing the extent to which the psychopathy trait correlates with human values in a predominantly female prison sample, found a positive relationship, although weak, between the socially deviant/antisocial lifestyle and experimentation (values linked to pleasure, sexuality and emotion).

For Loinaz et al. (2018), evaluating and using socioemotional and psychosocial variables in interventions with incarcerated people is of paramount importance when targeting the resocialization of this population. In the same vein, Wang et al. (2021) argue that successful social interaction is unfeasible when the ability of being aware of what other people are feeling and thinking is neglected, something that has been considered in the policies on resocialization promoted in other countries.

In England and Wales, for example, treatment programs are part of the routine in prisons, covering an average of 176 hours and addressing areas such as: motivation for change, understanding the offense, victim empathy, self-management and emotional management skills, intimacy, compulsivity, community engagement, charging behavior and relapse prevention (Barnett et al., 2011). In Spanish prisons, cognitive-behavioral interventions have been applied to men who commit violence against women, with the aim of reducing their aggression toward their victims. The 40-hour program is divided into 20 sessions. Among other dimensions, the program addresses motivational aspects and acceptance of responsibility for their crime, empathy training, socio-emotional self-regulation skills and prevention of relapse. Efficacy evaluations show that this type of intervention encourages participants to rethink their attitudes toward women and the use of violence as a response to conflicts (Echeburúa & Fernández-Montalvo, 2007).

When it comes to the Brazilian reality, previous studies sought to promote artistic and playful activities, based on the assumption that creating spaces that support subjective exchanges and new learning is crucial to developing resocialization actions in prison. For example, intervention studies in adolescents and adults in situations of deprivation of liberty show that actions aimed at health promotion and prevention (Costa et al., 2019), reflection on issues of work, sport and culture (Andrade & Vilas Boas, 2019), the use of music (Silva, 2018) and drawing workshops (Esteca & Andrade, 2018) contribute to increased awareness of self-care, the perception of oneself as a subject of law, reduction in aggression and greater engagement with didactic-pedagogical activities. They also reduce the stereotypes and prejudices of the general population toward prisoners.

These activities highlight the importance of art, education, leisure and dialogical spaces in prisons as tools for integration and re-socialization, as well as the promotion of mental health, emerging as a possibility to break away from criminal life by producing new meanings for their practices and future aspirations. Many aspects of cognitive functioning are important in this path to achieve this goal, such as social competence and adjustment, and a reduction in disruptive and antisocial behavior. According to Spink et al. (2014), the use of workshops as a methodological strategy produces data for scientific research and creates a favorable environment for negotiating meanings and dialogic exposure.

Despite this, few studies specifically seek to promote intervention in variables directly related to prosocial behavior, socioaffective development and psychological functioning as a whole. In view of the above, this study sought to review the effects of an intervention program aimed at promoting self-concept, empathy and basic values in incarcerated women in a city in the northeast of Brazil. To that, a program was designed with 12 workshops focusing on these themes and delivered over a period of three months.

Method

Participants

The participants in the study were 56 women imprisoned in a city in the hinterland of the state of Pernambuco, aged between 18 and 63 (M = 32.23, SD = 9.25), who were willing to take part in the study voluntarily. Women who were not literate (n = 5) and those who did not fill in the psychometric instruments properly (n = 2) were excluded from the sample. The remaining participants were randomly allocated into two groups by electronic raffle: Intervention Group (IG) (n = 15) and Control Group (CG) (n = 41).

Instruments

The Self-Concept Scale (Piers-Harris & Herzberg, 2002), in its version adapted and validated for Portuguese by Veiga (2006) - PHCSCS-2, was used to assess self-concept. The PHCSCS-2 is made up of 60 dichotomous questions that address factors such as behavior, intellectual and educational status, physical attributes and appearance, anxiety, popularity and satisfaction-happiness. In this study, the scale was adapted into Brazilian Portuguese with the support of five specialists, PhD in psychology and linguistics, who were invited to propose a translation for the statements faithful to the original items.

After that process, the researcher selected the most appropriate statements and applied them to a group of 15 people - young adults aged between 18 and 27, asking them to answer the scale and mark the items that were not easy to understand. The items were then revisited and applied to five women deprived of their liberty, who were asked about their understanding of the wording of the items. The adapted version proved to be easy to understand for the target audience.

It should be pointed out that the female prison population has a low level of education and, therefore, dichotomous questions (yes or no) facilitate the understanding. Another relevant aspect for choosing the instrument was the fact that behavioral factors and intellectual and educational status are closely linked to the ideal of resocialization, focused on work and education (Brazil, 1984). In the same vein, physical appearance, popularity and satisfaction may be important resources to develop coping strategies to deal with the adverse situations experienced in prison.

Empathy was measured using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1983), in its version adapted for Brazil by Sampaio et al. (2011), composed of 26 statements describing behaviors, feelings and characteristics related to empathy, along four dimensions: Perspective-Taking (PT), Fantasy (FS), Empathic Consideration (EC) and Personal Distress (PD).

PD is related to feelings of discomfort or anxiety in face of stressful situations, and is self-directed (focused on the self). EC, on the other hand, is focused on more prosocial behavior, motivated by a willingness to help other people. The other two components, PT and FS, are represented respectively by the ability to stand into situations experienced by other people, seeking to understand how they feel and stand in that situation, and by a similar cognitive ability related to fictional characters in films and books, for example (Sampaio et al., 2011).

The Basic Values Questionnaire (BVQ), developed by Gouveia (2003), was used to assess values. It consists of 18 specific items (values), distributed equally in six psychosocial subfunctions, described based on the characteristics of individuals guided by the following values: Experimentation, Suprapersonal, Interactive, Satisfaction, Existence and Normative (Gouveia, 2003; Gouveia et al., 2009).

The combination of the subfunctions allows for building up two axes that structurally organize them into type of motivator and type of orientation, which are, respectively: (1) Values as an expression of needs (idealistic needs or materialistic needs), and (2) Values as a guiding pattern for behavior (personal goals, central goals or social goals) (Gouveia, 2003; Gouveia et al., 2009).

In addition to the aforementioned instruments, a sociodemographic questionnaire was used containing questions about age, education, marital status, race/color, length of imprisonment, type of sentence, among others.

Procedures

The scales and questionnaire were administered by three researchers who had been previously trained to perform the procedures. Participants were divided into small groups of five individuals and taken to a room that offered suitable environmental conditions and physical space for the application of the instruments.

The research team members helped the women throughout the process of completing the scales and questionnaires, providing the necessary support to carry out the task. Instruments were presented separately, one by one, to the participants in order to avoid monotony and possible psychological and postural discomfort. These procedures were carried out twice in both groups (IG and CG) before and after the end of the workshops, following a pre- and post-test dynamic.

Intervention program

Only the IG was subjected to the interventions in the form of workshops in a room provided by the institution, where the prison school used to work, with a capacity for approximately 30 individuals. Meetings lasted 2 hours and were held once a week, always mediated by at least one facilitator and two assistants. The CG members maintained their regular institutional routines and did not take part in any kind of activity with the research team during the period of the workshops, apart from the psychological testing before and after the intervention.

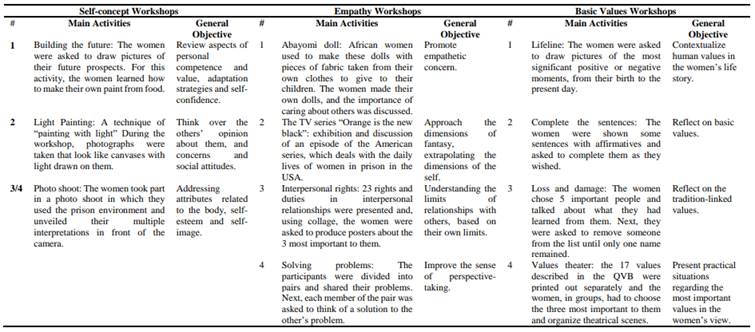

The workshops lasted three months. The meetings included experiential moments during which activities were developed intending to promote the participants’ self-concept, empathy and basic values, so that the women’s experiences and life history arouse as learning and reflection devices. Table 1 shows a description of the activities and general objectives of each meeting.

In order to gather qualitative data, participant observation and the construction of a field diary based on the women’s speeches during the workshops were the data collection techniques used. Participant observation is an important tool for understanding the dynamics of the group, giving the researcher a holistic and natural view of the scenario being observed (Alferes et al., 2017).

Information on the women’s mood was collected after each meeting. The activity was carried out at the end, intending to find out their feelings regarding the meetings and after carrying out the activities.

The research was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of the São Francisco Valley (CEP-UNIVASF), and approved (CAAE: 68528517.2.0000.5196) before any activities began. Workshops began only after the institutional authorization had been granted and participants had signed the Informed Consent Form.

Data Analysis

In this study, a quantitative-qualitative approach was elected to review data in order to allow encompassing more of the complexity of the phenomena studied. Thus, data from the psychometric instruments was tabulated and organized in the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, version 2016, and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0, adopting a significance level of p < .05. The Shapiro-Wilk test pointed out that data relating to the scales did not follow a normal distribution and so it was decided to use non-parametric tests to carry out the inferential statistics. In order to apply the inferential tests, only the protocols of the participants who had completely answered all the scales were included. Data from 15 members of the intervention group and 16 of the control group were reviewed.

The qualitative data is the result of the analysis of field diary records, notes and materials produced during the workshops with the participants. It is a description and analysis of subjective aspects perceived and anchored in the current literature on the subject, as an analytical operator. These data reflect the impressions and experiences of the team members who worked directly on the interventions with the participants, and who met periodically to assess the progress of the intervention program.

Results

Quantitative analysis

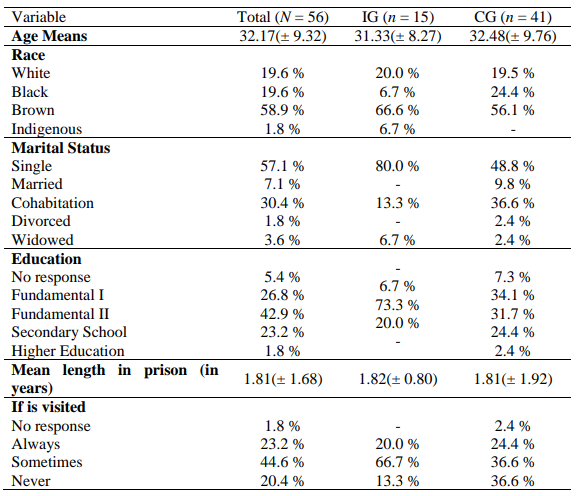

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic profile and prison history of participants. The majority of the women is self-declared brown, with low levels of schooling, single and sometimes receive visits.

Spearman’s test was used to check for correlations between the dependent and independent variables in this study. It was found that the normative subfunction significantly correlated with prison length (p = .410; p < .001). The normative subfunction correlated positively with general empathy (p = .335; p < .05).

The Kruskal-Wallis test suggested a significant difference in the items satisfaction and happiness (χ2 =12.09; p = .002) and popularity (χ2= 8.82; p = .012), in the sense that women who always receive visits scored higher on these components of the self-concept than those who do not receive visits and those who receive them only sometimes.

The Friedman test showed a difference between the six subfunctions of values when compared to each other. The Wilcoxon test indicated that the existence and normative subfunctions (Z = -0.880; p = .37) do not differ from each other but differ significantly from all the others (all p-values, when comparing the subfunctions two by two, are less than 5%).

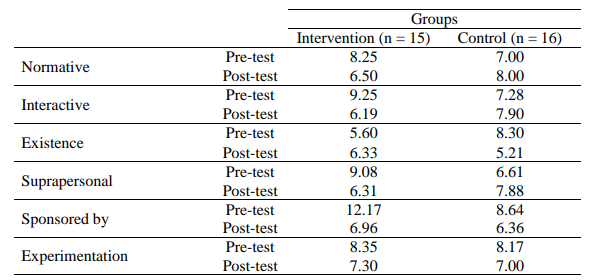

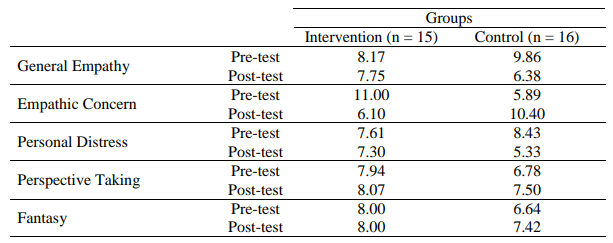

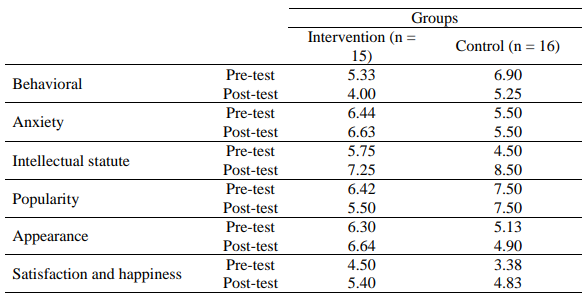

With regard to testing the effects of the intervention, the Wilcoxon test did not find any significant variation between the pre- and post-test in any of the components of Empathy, Self-Concept and Basic Values, neither in the intervention group (IG) nor in the control group (CG). In addition, the Mann-Whitney test showed no differences between the IG and CG in the pre- and post-test in any of these variables. Tables 3, 4 and 5 show the mean ranks for Empathy, Self-Concept and Basic Values, depending on the group of participants and the moment of testing.

Table 3: Average scores in each dimension of empathy, according to the groups of participants and the moment of testing

Table 4: Average scores in each dimension of self-concept, according to the groups of participants and the moment of testing

Qualitative analysis

With regard to the meetings in the Self-concept workshops, photography was the most successful resource, both in the meeting that used the Light Painting technique and in the photography shoot. Light Painting is a photographic lighting technique in which, with the aid of a flashlight, a dark environment and a camera set to long exposure, one can paint whatever they want with the light. This technique raised a lot of interest among the women, especially when it comes to handling the cameras and flashlights and then seeing how the photos turned out.

Once all the bureaucratic steps had been completed and the ethical aspects respected (terms of consent and image rights), the photo shoot was conducted. This was yet another activity that used visual resources, this time for an approach more focused on self-image. At first, participants were reticent about the activity, but this impasse was soon resolved. Most of them had prepared for the day, put on make-up, done their hair, chosen clothes, and the photographs were taken in different environments, and little by little they undressed in front of the cameras. This is not a figure of speech, because little by little they got literally undressed.

Through the photographs, the women raised several questions about how they saw themselves, they talked about the physical changes after imprisonment and how much this process changed their perception of themselves. The discussions focused on accepting one’s own body and seeing it as beautiful, despite the adverse conditions.

In the Empathy workshops, the activities that stood out were those dealing with interpersonal rights and the activity of solving other people’s problems. Among the list of 23 rights that assume a duty in the same direction toward the other, the group chose two as the most important: the right to be treated with respect and dignity, and the right to stopping and thinking before acting.

The right to stopping and thinking before acting facilitated approaching the crimes they had committed, the lack of empathy and, above all, the possibility of changing behavior through reflection. Thinking before acting means pondering before choosing, looking for the most appropriate way to resolve a given situation. Solving the other’s problem seemed like an easy task, but taking on the other’s perspective and solving the problem in the best possible way (for the other) was a challenge for the participating women. Face to face with each other, tears and hugs abounded during this activity. When space was opened for discussion, the women said that they had not yet realized that one woman’s problem was so close to the other’s problem.

In relation to the meetings in the Basic Values workshop, the loss and damage activity differed from the others not because of its adherence, but because it was one of the activities in which women were most resistant. The activity could not advance with so many complaints, so the team had to reorganize it several times to get it done.

The initial activity consisted of writing down the names of some important people in their lives, then saying what they had learned from the person and removing the name of each of them until only one remained. However, they did not want to remove anyone as for them all the names written down mattered. This act showed more about their values than the aim of the proposed activity. The importance of affection and social support emerges, feeling that they are not alone in the world and that there are people they can count on, regardless of successes and/or failures.

Asking women who suffer from the systematic abandonment of their spouses, family, institutions and a large part of society, even if imaginary, to abandon the people who remain with them is, to say the least, incoherent. The persons who remain are often the ones for whom the women say it is worth abandoning the world of crime.

Finally, the use of a technique to start the meetings and connect the women with the workshop environment produced interesting results: it was a moment we called “Journey” in which, with their eyes closed, following a facilitator’s narration, listening to the sound of rain, with the lights dimmed, the women were invited to imagine a place where they would like to be. At the end of the dynamic, many women were lying on the floor in a fetal position, crying. It should be noted that it happened in a place where people are demanded to be strong, never show weakness, a space where the expression of repressed feelings becomes contravening.

Two emotions stood out in the women’s evaluations at the end of the workshops: the first was happiness, which is believed to be linked to the relaxed atmosphere and the emotional exchanges made possible at the meetings. The other emotion was that of being “confused”, thoughtful or distressed, as they verbalized it, which can be considered to be a critical and reflective opening up of their condition.

Discussions and Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of an intervention program to promote empathy, values and self-concept in incarcerated women from a prison unit in the hinterland of Pernambuco. The efficacy of intervention programs using workshops and other contemplative activities in empirical studies has been proven to promote constructs such as empathy (Dutra, 2020; Rodrigues & Silva, 2012) and self-concept (Coelho et al., 2016) in other populations. Similarly, studies on basic values have confirmed the importance of this construct in predicting behavior (Medeiros et al., 2015; Monteiro et al., 2017).

The data produced from the statistical analyses suggest that there were no significant variations in Empathy, Values and Self-Concept after a period of intervention. These results may be associated with the intervention duration.

Other limitations, such as the use of non-probabilistic samples, the non-use of the recidivism rate and no prior analysis of the levels of psychopathy in the sample, mean that the evidence reported here should be viewed with caution (Amorim-Gaudêncio et al., 2023; Roche et al., 2011). The limitations of psychometric scales when they are applied to participants with low levels of education or in forensic samples (Barnett et al., 2011; Domes et al., 2013) deserve attention.

It should be noted that a considerable barrier to the implementation and enhancement of workshops outcomes was the configuration of the prison environment, which is hostile, rigid, violent and promotes vulnerabilities. Overcrowding, unsuitable structures, unsanitary conditions, recidivism, police violence, drug trafficking, lack of social support are some of the chronic problems of the Brazilian prison system, well known to society (Brazil, 2016). The prison where this research was carried out was even nicknamed by Santos and Rios (2018) as a “cortiço-prisão” (hovel-prison) precisely because of the structural, sanitary and humanitarian deficits found in the establishment, positioning it as a “jerry-rigged of the (Brazilian) legal-criminal system”.

There is a pressing need to review structural aspects of our justice and public security system, especially those supportive to the process of social reintegration. Being imprisoned is far more than losing freedom, as imprisonment engenders many vulnerabilities. The collateral repercussions of deprivation of liberty are sometimes more serious than the sentence (Giacóia et al., 2011).

A qualitative analysis - based on the activities developed in the workshops in line with the current literature on the subject - suggests that the space designed is in a position to promote cultural, recreational and artistic activities that are so important for the resocialization process. Dialogical spaces such as those created during the interventions are capable of encouraging the inmates to identify and recognize problems with their self-esteem and to rethink their attitudes (Barnett et al., 2011; Echeburúa & Fernández-Montalvo, 2007), contributing toward raising awareness about their rights (Maciel, 2018; Silva, 2018) and bringing new meanings to the experience of serving their sentence from a non-punitive perspective.

Having the chance to re-read their life story through the crossings provided by the meetings and being affected by this opens up a great parallel to rethink sensitive points aiming at promoting the social reintegration of these women. This is an important axis of discussion that deals with how to endow the sentence of deprivation of liberty with more humanistic configuration, transforming it into an emancipatory rather than just punitive sentence (Andrade & Vilas Boas, 2019; Maciel, 2018; Silva, 2018).

By the end of the workshops, the prominence of feelings of distress reported by participants when asked to express their emotions may suggest that the meetings succeeded in bringing about potential cognitive-affective and, consequently, behavioral changes. This finding is in agreement with the considerations by Andrade and Vilas Boas (2019), who point out that the actions developed in these spaces go beyond the physical contours of the workshops, expanding into the lives of all the actors involved, promoting behavioral changes and enabling individuals to have autonomy and criticality over their own being. Likewise, dialogical spaces are capable of promoting mental health and care (Ireland & Lucena, 2013).

Working with psychological constructs in workshops in the prison environment implied addressing aspects of everyday life. As such, it is not just a matter of teaching concepts or describing them academically. It means that the very experience of these women was pedagogical, evidencing how important these themes are for their functional development (Ireland & Lucena, 2013).

The methodologies used in the workshops align the participating women with their context, preparing them for life and its hardships, rescuing their sense of self-worth and belonging. It gives these women the chance to get rid of stereotypes and stigmas rooted in their historical condition, and to build new and more functional concepts about themselves and less painful experiences in the world (Bagio et al., 2018; Gohn, 2006; Spink et al., 2014).

The workshops were configured as a non-formal learning space enabled in prison, based on the historicity of these individuals. These spaces were also able to empower incarcerated women to become citizens of the world, in the world, envisioning other ways of being and perceiving the world around them and in their social relationships (Gohn, 2006).

The main contributions of the workshops include: offering incarcerated women a pedagogical and welcoming space, with contingencies very different from the prison environment, through which they were encouraged to experience their emotions and feelings, talk openly about their experiences, expose their doubts, fears, aspirations and anxieties.

The non-statistically significant results may well reflect the fact that the scales did not capture the subjective components of empathy, self-concept and values in the population studied, emphasizing the importance of integrating quantitative and qualitative data in order to understand the phenomenon in a more comprehensive way. Methodological strategies relevant to the participants’ schooling profile should be used.

The assessment and promotion of self-concept, empathy and basic values can potentially drive the processes of psychological intervention in prison, and subsidize penal outcomes. This dynamic process should consider the multidimensionality of variables and the complexity of the prison population. The instruments should be able to measure these traits, properly reflecting the objective of the assessment and the proposed interventions (Barnett et al., 2011; Echeburúa & Fernández-Montalvo, 2007; Loinaz et al., 2018). There is also a need for other researchers to look into the development and testing of assessment and intervention methodologies that fit into the reality of these people, bringing empirical-theoretical contributions and subsidizing other interventions in this type of scenario.

REFERENCES

Alferes, V. R., Castro, P. A., & Parreira, P. M. (2017). A Observação Participante enquanto metodologia de investigação qualitativa. Investigação Qualitativa em Ciências Sociais, 3, 724-733. [ Links ]

Amorim-Gaudêncio, C., Moura, J., Lima, G., Roquete, G., de, R., Felício, L., & Alessandra, D. (2023). Relationship between psychopathy, personality and human values in a prison sample, 28(1), 135-148. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712023280111 [ Links ]

Andrade, A. F. D., & Vilas Boas, C. C. (2019). Ressignificar a experiência da medida socioeducativa numa perspectiva não punitivista: a experiência do Projeto de Extensão Laços. Conecte-se! Revista Interdisciplinar de Extensão, 3, 41-57. [ Links ]

Antunes, D. T. N. (2012). Agressores sexuais de menores e reclusão: estudo exploratório sobre personalidade, impulsividade e espontaneidade (Dissertação de doutorado). ISPA-Instituto Universitário. [ Links ]

Bagio, V. A., Althaus, M. T. M., & Zanon, D. P. (2018). Didática na Docência Universitária em Saúde: Metodologias Ativas e Avaliação. Appris Editora e Livraria. [ Links ]

Barnett, G. D., Wakeling, H. C., Mandeville-Norden, R., & Rakestrow, J. (2011). How useful are psychometric scores in predicting recidivism for treated sex offenders? International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56(3), 420-446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x11403125 [ Links ]

Basílio, L. R. M., Roazzi, A., Nascimento, A. M. D., & Escobar, J. A. C. (2017). Self-concept dialectical transformation: A study in a women's prison. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 34, 305-314. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752017000200011 [ Links ]

Batson, C. D. (2009). These Things Called Empathy: Eight Related but Distinct Phenomena. Em J. Decety & W. Ickes (eds.), The Social Neuroscience of Empathy (pp. 3-16). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262012973.003.0002 [ Links ]

Brasil. (1984). Lei nº 7.210, de 11 de julho de 1984. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l7210.htm [ Links ]

Brasil. (2017). Levantamento Nacional de Informações Penitenciárias Infopen Mulheres (2a ed.). [ Links ]

Christopher, G., & McMurran, M. (2009). Alexithymia, empathic concern, goal management, and social problem solving in adult male prisoners. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15(8), 697-709. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802516240 [ Links ]

Coelho, V. A., Marchante, M., & Sousa, V. (2016). O impacto dos programas atitude positiva sobre o autoconceito na infância e adolescência. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 21(2), 261-280. [ Links ]

Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público. (2016). A Visão do Ministério Público sobre o sistema prisional brasileiro. https://acortar.link/6pA3go [ Links ]

Costa, D. R. S., Campos, F. V. A., Lira, M. O. S. C., Guimarães, M. C., Souza, S. T. H..., & Pereira, V. C. A. (2019). Uso de metodologias ativas em práticas educativas em saúde com adolescentes em situação de acolhimento institucional: relato de experiência. Revista de Educação da Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco, 9(20), 298-327. [ Links ]

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113-126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113 [ Links ]

Day, A., Mohr, P., Howells, K., Gerace, A., & Lim, L. (2011). The Role of Empathy in Anger Arousal in Violent Offenders and University Students. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56(4), 599-613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x11431061 [ Links ]

Domes, G., Hollerbach, P., Vohs, K., Mokros, A., & Habermeyer, E. (2013). Emotional empathy and psychopathy in offenders: An experimental study. Journal of Personality Disorders, 27(1), 67-84. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2013.27.1.67 [ Links ]

Drayton, L. A., Santos, L. R., & Baskin-Sommers, A. (2018). Psychopaths fail to automatically take the perspective of others. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(13), 3302-3307. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721903115 [ Links ]

Dutra, M. P. (2020). Avaliação de estratégias para a redução de comportamentos agressivos em crianças de 9 a 12 anos (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Federal da Paraíba. [ Links ]

Echeburúa, E., & Fernández-Montalvo, J. (2007). Male batterers with and without psychopathy. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 51(3), 254-263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x06291460 [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial Development. Em N. Eisenberg, W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development (pp. 646-718). Wiley. [ Links ]

Esteca, A. C. P., & Andrade, L. D. (2018). Desenhando a liberdade: A experiência de oficinas de desenho no sistema prisional. Cadernos RCC, 5(2002), 255-261. [ Links ]

Formiga, N. S., & Gouveia, V. V. (2005). Valores humanos e condutas anti-sociais e delitivas. Revista Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 7(2), 134-170. [ Links ]

Gehrer, N. A., Duchowski, A. T., Jusyte, A., & Schönenberg, M. (2020). Eye contact during live social interaction in incarcerated psychopathic offenders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11(6), 431-439. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000400 [ Links ]

Giacóia, G., Hammerschmidt, D., & Fuentes, P. O. (2011). A prisão e a condição humana do recluso. Argumenta (FUNDINOPI), 15, 131-161. [ Links ]

Gohn, M. G. (2006). Educação não-formal, participação da sociedade civil e estruturas colegiadas nas escolas. Ensaio: avaliação e políticas públicas em educação, 14(50), 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-40362006000100003 [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V. (2003). A natureza motivacional dos valores humanos: evidências acerca de uma nova tipologia. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 8, 431-443. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-294X2003000300010 [ Links ]

Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., Fischer, R., & Coelho, J. A. P. D. M. (2009). Teoria funcionalista dos valores humanos: aplicações para organizações. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 10, 34-59. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-69712009000300004 [ Links ]

Hoffman, M. L. (2000). Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ireland, T. D., & Lucena, H. H. R. (2013). O presídio feminino como espaço de aprendizagens. Educação & Realidade, 38(1), 113-136. https://doi.org/10.1590/s2175-62362013000100008 [ Links ]

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2004). Empathy and offending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(5), 441-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2003.03.001 [ Links ]

Korponay, C., Pujara, M., Deming, P., Philippi, C., Decety, J., Kosson, D. S., Kiehl, K. A., & Koenigs, M. (2017). Impulsive-antisocial psychopathic traits linked to increased volume and functional connectivity within prefrontal cortex. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(7), 1169-1178. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsx042 [ Links ]

Loinaz, I., Sánchez, L. M., & Vilella, A. (2018). Understanding empathy, self-esteem, and adult attachment in sexual offenders and partner-violent men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(5-6), 2050-2073. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518759977 [ Links ]

Maciel, D. M. P. (2018). A Prata e a Semente: Atividades Socioculturais em Prisões do Norte de Portugal (Tese de doutorado). Universidade de Nova Lisboa. [ Links ]

Martinez, A. G., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2014). Can perspective-taking reduce crime? Examining a pathway through empathic-concern and guilt-proneness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(12), 1659-1667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214554915 [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. D., Pimentel, C. E., Monteiro, R. P., Gouveia, V. V., & Medeiros, P. C. B. (2015). Valores, atitudes e uso de bebidas alcoólicas: Proposta de um modelo hierárquico. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão (Online), 35, 841-854. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703001532013 [ Links ]

Monteiro, R. P., Medeiros, E. D. D., Pimentel, C. E., Soares, A. K. S., Medeiros, H. A. D., & Gouveia, V. V. (2017). Valores humanos e bullying: idade e sexo moderam essa relação? Trends in Psychology, 25, 1317-1328. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2017.3-18Pt [ Links ]

Pavarino, M. G., Del Prette, A., Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2005). O desenvolvimento da empatia como prevenção da agressividade na infância. Psico, 36(2), 3. [ Links ]

Piers-Harris, E. V., & Herzberg, D. S. (2002). Piers-Harris Children´s Self-Concept (2nd edicition). https://acortar.link/zHM3Au [ Links ]

Robinson, E. V., & Rogers, R. (2015). Empathy faking in psychopathic offenders: The vulnerability of empathy measures. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(4), 545-552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9479-9 [ Links ]

Roche, M. J., Shoss, N. E., Pincus, A. L., & Ménard, K. S. (2011). Psychopathy moderates the relationship between time in treatment and levels of empathy in incarcerated male sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(2), 171-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063211403161 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, M. C., & da Silva, R. D. L. M. (2012). Avaliação de um programa de promoção da empatia implementado na educação infantil. Estudos e pesquisas em Psicologia, 12(1), 59-75. https://doi.org/10.12957/epp.2012.8304 [ Links ]

Sampaio, L. R., Santos, T. L. S., & Camino, C. P. S. (2021). Construção e evidências de validade da escala multidimensional de empatia para crianças. Avaliação Psicológica, 20(2), 151-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.15689/ap.2021.2002.20742.03 [ Links ]

Sampaio, L.R., Guimarães, P.R.B., Camino, C.P.S., Formiga, N.S., & Menezes, I.G. (2011). Estudos sobre a dimensionalidade da empatia: tradução e adaptação do Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Psico (PUC), 42(1), 67-76. [ Links ]

Santos, L. D. P. B., & Rios, L. F. (2018). Sexualidades e resistências: uma etnografia sobre mulheres encarceradas no Sertão Pernambucano. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 38, 60-72. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-3703000212379 [ Links ]

Silva, E. M. (2018). Oficina de música no contexto socioeducativo: trajetórias e cidadania. Revista Projeção Direito e Sociedade, 9(2), 96-109. [ Links ]

Spink, M. J., Menegon, V. M., & Medrado, B. (2014). Oficinas como estratégia de pesquisa: articulações teórico-metodológicas e aplicações ético-políticas. Psicologia & Sociedade, 26(1), 32-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822014000100005 [ Links ]

van Zonneveld, L., Platje, E., de Sonneville, L., van Goozen, S., & Swaab, H. (2017). Affective empathy, cognitive empathy and social attention in children at high risk of criminal behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(8), 913-921. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12724 [ Links ]

Vaz-Serra, A., & Pocinho, F. (2001). Auto-conceito, coping e ideias de suicídio. Psiquiatria Clínica, 22(1), 9-21. [ Links ]

Veiga, F. H. (2006). Uma nova versão da escala de autoconceito: Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (PHCSCS-2). Psicologia e Educação, V(1), 39-48. [ Links ]

Wang, S., Wang, X., Chen, Y., Xu, Q., Cai, L., & Zhang, T. (2021). Association between relational trauma and empathy among male offenders in China. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 31(4), 248-261. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.2208 [ Links ]

Webster, S. D., Bowers, L. E., Mann, R. E., & Marshall, W. L. (2005). Developing Empathy in Sexual Offenders: The Value of Offence Re-Enactments. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 17(1), 63-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320501700107 [ Links ]

Data availability: The dataset that supports the results of this study is available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/snw4t/files/osfstorage).

Funding: This project received support from the Foundation for the Support of Science and Technology of the State of Pernambuco (Fundação de Amparo a Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Pernambuco, FACEPE) and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, CAPES).

How to cite: Pereira, E. F. M., Sampaio, L. R., & Anacleto, F. N. A. (2023). Promotion of empathy, self-concept and basic values: an intervention in a female prison. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-2823. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2823

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript. P. P. C. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; L. R. in a, b, c, d, e; F. S.-C. in a, c, d, e.

Received: February 12, 2022; Accepted: August 23, 2023

texto en

texto en